13

Tailoring the staged framework

- Tailoring - making it work for everyone

- Four types of project

- Fitting into the staged framework

- Small stuff, or "simple" projects

- "Just do it" projects: loose cannons

- Agile or rapid "projects"

- Concurrent engineering

- Projects which impact a lot of people

- Big stuff, or projects, subprojects and work packages

- The extended project life cycle

The staged approach requires that, by the time you reach the development gate, you know, with a reasonable level of confidence, what you are going to do, how you are going to do it and who is accountable for seeing it is done.

Tailoring – making it work for everyone

The previous chapters have taken you through a project management framework you can use for each of your projects. This framework leads the project sponsor and project manager on a journey to ensure quality and purpose are built into the project from the start and developed further as you proceed to your end-point. If your organization also has a common life cycle, then all projects undertaken in your organization can be referenced to the same, defined, and known set of stages; it makes managing a lot of projects much easier and simplifies the associated information systems. You may have wondered, as you read this book, whether this implied “one size fits all” approach is practical. Can you really direct and manage a small internal project using the same methods and life cycle as you would for a major multi-million pound endeavour? Common sense tells you this cannot be right . . . and usually common sense is right! All organizations are different, with an emphasis on different types of project but the principles and building blocks in the book are applicable to all.

In Chapter 4, you learnt how to tailor the life cycle in terms of deciding the number of stages you need and what to call them. In this chapter we will look at how we can adapt the standard project framework to suit different circumstances; we will “tailor” the approach for specific needs. I can’t tell you what every circumstance is likely to be but, by looking at a range of different examples, I can help you develop the mind-set to enable you to do this for yourself.

In this chapter we will look at how we can adapt the standard project framework to suit different circumstances.

Four types of project

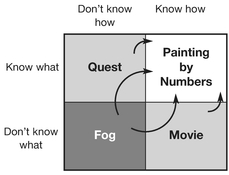

In his book, All Change! The Project Leader’s Secret Handbook, Eddie Obeng describes four types of projects, each of which deals with a different kind of change. I have shown these in Figure 13.1. You should know why you want to do the project in the first place but, depending on circumstances, you may or may not know what you want or how to achieve it.

Painting by numbers

What are often termed as “traditional projects” tend to be of this kind. These projects have clear outputs and a clearly defined set of activities to be carried out. You know what you want to achieve and how you will achieve it.

This project is often formally called a closed project.

Figure 13.1 Different types of change project

If you know what you are doing and how you are going to do it, you have a “painting by numbers” project. If you know how but not what, you have a “movie”. A “quest” is when you know what you want, but not how you will achieve it. Finally a “fog” is when you don’t know what you want, nor how to achieve it.

Going on a quest

You are clear on what is to be done but clueless as to the means (how) to achieve it. It is named after the famous quest for the Holy Grail. The secret of this type of project is get your “knights” fired up to seek for solutions in different places at the same time and ensure that they all return to report progress and share their findings on a fixed date. You can then continue to send them out, again and again until you have sufficient knowledge of how you can achieve your objectives.

Quests are invaluable as they give “permission” for your people to explore “out of the box” possibilities. Be warned, if you don’t keep very strict control over costs and timescales they are notorious for overspending, being very late, or simply delivering nothing of benefit, hence you have to bring your “knights” back regularly to see how they are getting along.

This project is formally called a semi-closed project.

Making movies

In this type of project, you are very sure of how you will do something but have no idea what to do. Typically, your organization has built up significant expertise and capability and you are looking for ways to apply it. There must be several people committed to the methods you will use.

This project is formally called a semi-open project.

Walking in the fog

This type of project is one where you have no idea what to do or how to do it. It is often prompted as a reaction to a change in circumstances (e.g. political, competitive,

Table 13.1 Project types

| Project type | Type of change it helps create or man | Application |

| Painting by numbers | Evolutionary | Improving your continuing business operations |

| Going on a quest | Revolutionary | Proactively exploring outside current operations and ways of working (recipe) |

| Making a movie | Evolutionary | Leveraging existing capabilities |

| Lost in a fog | Revolutionary | Solving a problem or exploring areas outside your current operations and ways of working (recipe) |

Source: Adapted from Eddie Obeng Putting Strategy to Work (London: Pitman Publishing, 1996).

social), although it can be set off proactively. You know you have to change and do something different; you simply can’t stay still; you also may need to act quickly. This project needs, in some ways, to be managed like a quest. You need to have very tight control over costs and timescale; you need to investigate many options and possible solutions in parallel. Like a quest, these projects can end up in delivering nothing of benefit unless firmly controlled.

This project is formally called an open project.

Each of these project types has different characteristics and requires different leadership styles. They are also suited for different purposes (as shown in Table 13.1 above).

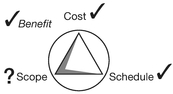

Fitting into the staged framework

The staged framework requires that, by the time you reach the development gate, you know, with a reasonable level of confidence, what you are going to do and how you are going to do it. That is to say, at the development gate you will have a painting by numbers project (see Figure 13.2). The investigative stages are there to give you the time, resources, and money to discover an appropriate solution to your problem and finalize your plan. The proposal should have stated why you need the project, however, your level of background knowledge will differ for each proposal you want to address. This will have a considerable impact on the way you undertake the investigative stages and the level of risk associated with the project at the start. Painting by numbers projects tend to be less risky than the other types, but not always. Figure 13.3 shows this in a different way: a “normal” project (if there is such a thing!) can change from being a quest, movie, or fog to painting by numbers as it moves through the project life cycle. The clarity of your scope, timescale, costs, and benefits will improve as you gain more knowledge. In addition, as we earlier learned (Figure 4.2), the level of risk should decrease as you progress through the project.

Figure 13.2 Creating a project you can implement

The staged framework requires, by the time you reach the development gate, that you know what you are going to do and how. That is to say, at the development gate, you will have a painting by numbers project. You may, however, start off as any of the project types – the investigative stages are the means by which you define your solution.

Figure 13.3 Getting to paint by numbers

A “normal” project can change from being a “quest”, “movie,” or “fog” to “painting by numbers” as it moves through the project life cycle. The clarity of your scope, timescale, costs, and benefits will improve as you gain more knowledge.

Just to make your day, there are circumstances when you would allow a project to continue past the development gate as a fog, movie, or quest. For example, when the risks of not proceeding outweigh the risks of proceeding. The level of risk would be higher than under normal circumstances but that is your choice. The “game” of projects has principles but few rules. Directors have to direct and managers have to manage; that is your role. If an action makes common sense, do it and do it openly, keeping the risk firmly in mind.

![]() Rules and exceptions

Rules and exceptions

Some companies tie themselves up in process-driven rules bound neatly in files with quality assurance and control labels. These rules often go to great levels of detail covering every conceivable scenario.

I would argue that this is a fruitless exercise. It is better to have a few basic principles and make sure your people understand why you need them and how they help them do their jobs. You can then handle the odd “exception” using “exception management,” dealing with it on its own merits within the principles you have laid out. In other words, give the managers and supervisors the freedom to do their jobs and exercise the very skills you are paying them for.

If you write rules at a micro-level:

- you might get them wrong;

- they might be used in way you never conceived and contrary to what you wanted;

- you will spend a long time writing them thus diverting your attention from the real issues;

- people will look for “legitimate” ways round them, playing with words in a legalistic game;

- you will cause people to break them (perhaps through ignorance) and then risk making them feel bad about it;

- you risk employing an army of policemen to check that the rules are being adhered to.

Remember, you are trying to run a project, not create a penal code.

Small stuff, or “simple” projects

“I now understand gates and stages,” you may say, “but isn’t it all a bit too much for smaller, simple projects?” Let us take the example of what I would term a “simple” project differs from the type of project normally associated with staged approaches and how you can deal with them using the same management framework.

A normal project may start off as painting by numbers, a fog, a quest, or a movie. The investigative stages are worked through until you are confident (say, around 85 to 95 per cent) the required benefits can be achieved. At the detailed investigation gate you will have narrowed your options down and have approval and funding to complete the detailed investigation stage. At the development gate you would have approval to complete the project as a whole – it has become a painting by numbers project.

With a simple project, you may know a great deal about it before you even start. By the time you finish the initial investigation stage you might have fully defined the project outputs and your plan; your confidence level will be as high as it is normally for a more complex project at the development gate (Figure 13.4), so undertaking the detailed investigation stage is either trivial or unnecessary.

Full authorization to complete the project can therefore be given at the detailed investigation gate (see Figure 13.5). This doesn’t mean you can bypass the remaining gates, you still need to have reviews and checks to ensure ongoing viability. If you omit the detailed investigation stage you must meet the full criteria of the development gate before you start the develop and test stage.

In this way, you have used the principles of the framework, checking at every gate but you have avoided doing any unnecessary work. Making the key control documents, initial business case and business case have identical content enables this to happen without the need to duplicate any documentation.

Figure 13.4 Simple project

A simple project can be defined very rigorously by the end of the initial investigation stage.

“Just do it” projects: loose cannons

Figure 13.5 The stages for a simple project

The top diagram represents a project where some detailed investigation work still needs to be done. Nevertheless, the level of confidence is high enough to authorize and fund the project to completion.

The lower diagram represents an even simpler case where no further investigative work needs to be done. The project is checked against the criteria for the development gate and, if acceptable, moves straight into the develop and test stage.

There are cases when senior management will issue an edict to finish a project by a certain time, whatever the cost. In certain circumstances, this is a valid thing to do, especially when the survival of the organization requires it. Such projects must be treated with extreme caution as often they come about as an executive’s “pet project” and may have little proven foundation in business strategy. I have found that there are very few instances in companies where something needs to be done regardless of the costs and consequences. These projects invariably start off being optimistic and end up bouncing around the organization demanding more and more resources are assigned to it without delay. Consequently, there can be considerable impact on day-to-day operations as well as significant delays to other projects. Remember, delayed projects lead to delayed benefits. They also tend to be very stressful for those associated with them. The damage left in the wake of such projects can be awesome even if they appear to succeed!

Most organizations can cope with one of these kinds of projects – occasionally. Most organizations cope better if there aren’t any. If you believe one is necessary, it should still be aligned into the project framework as closely as possible and managed as an “exception”. Before starting, consider:

- Why am I doing this?

- Is it really far more important than everything else?

- Am I really sure what I am doing?

There must be very compelling reasons to allow a loose cannon project to start. Responding to a problem by panicking is not usually a good enough reason! Using the issue breakthrough technique is a better starting point (see Workout 24.1).

You must be absolutely clear what other activities and projects it can be allowed to disrupt. You can create more problems, for yourself and for others, than you will solve. You must consider the real “cost/benefit” and take into consideration the inefficiencies and lost or delayed benefits from the disrupted projects. After all that, if you really must do it then:

- undertake an initial investigation first so you can make an informed decision;

- keep the project as short as possible (say, three months maximum). If you need longer, chunk the project up into smaller pieces.

- No matter what project you want to undertake, always carry out an initial investigation to help you decide, on an informed basis, the most appropriate way to take the project forward (e.g. normal, simple, or other approach);

- Having decided your approach, record it in your initial business case.

Agile or rapid “projects”

Harnessing agile concepts

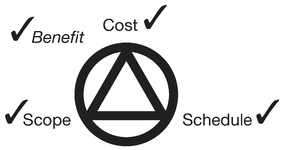

Let’s now consider the concept of “agile”, or what used to be commonly called “rapid” projects. Agile delivery techniques involve iterative requirements definition, design and delivery, using either a prototype platform or the actual operational platform, where work is undertaken within a fixed budget and timescale, but where the scope is varied to suit (see Figure 13.6). If a team runs out of time or money, the scope is reduced in order to meet the time/cost targets. Provided a predefined, minimum scope is delivered, the work should remain within its area of benefit viability. In many ways, it is like a “simple” project, except the scope is variable within known limits. You are, therefore, able to assign resources to it with confidence, knowing when they will become available for other projects. In this respect, agile approaches are a way to deal with “Quest” projects, with the sprints representing the periods of time the knights are out hunting for the Holy Grail. They also apply to “Foggy” projects, where the knights are simply looking something, but they are not sure what it is until they find it.

Agile project management?

Be very careful about how you relate “agile delivery” to “project management”. Often people talk about traditional project management being “waterfall” and advocating agile project management instead. If you are a software developer, this perception can make sense; software developers tend to equate what they term as traditional project management with “big design up front” and “waterfall” methods for developing the code, moving sequentially from requirements definition, system architecture, software design, build, testing and deployment. Software developers are, however, only concerned with building code and often see this work as “their project”. Their view is other activities, such as building and deploying the hardware, developing processes and training, rolling out the new tools to users and ensuring their use are somebody else’s problem, outside “their project”. If the software developers are from a supplier or contractor, then the coding may indeed be the limit of the scope for “their project”; they develop code for a fee, which represents the benefits they gain.

Figure 13.6 “ Agile ” project

A project using agile techniques has fixed timescale, cost, and minimum benefits. Scope varies to suit these constraints.

- Don’t think in terms of “agile project management”, but rather “agile delivery”;

- Consider “agile techniques” as applying to work packages, not to whole projects;

- Don’t try to map agile steps into specific project life cycle stages; put your agile managed work packages in whatever life cycle stage makes sense, bearing in mind risk and dependencies on other work.

In an organization, with its own development resources, such a limited view can be damaging to the business and you should start worrying if you hear people talk about the “IT project” and the “business project” as separate. In this book, I advocate all projects should be business-driven and the scope of a project should include everything needed to change a business and start realizing the benefits. From this viewpoint, developing code is simply an essential package of work which, combined with the rest of the work, forms a complete, business-led project. Agile is a delivery or development approach used for the software outputs and its activities can take place in any of The Project Workout’s life cycle stages. The other outputs, such as training, would be developed using whatever processes or methods are appropriate. Do not try to map agile steps to project stages; agile steps can happen within any project stage so there is no definitive mapping, just as any other specialist work may not have unique mapping. For example, staying with the IT enabled projects, usually, user training cannot be designed until after the code has been tested and training design activities, follow after software test activities; “design activities” do not all happen at the same time, nor within the same project stage.

![]() The CIO of a global company was trying to improve the productivity of his developers, who had to work on a number of separate service platforms. After careful thought, he decided agile was the answer to all his concerns and set about creating an environment in which agile would thrive. This included redesigning office spaces, furniture and equipment for the agile teams, developing a reference web site with guidance on good practice, behavioural training and setting up a network of coaches to help each team adopt and use the methods correctly. It was all well thought through, properly funded and done correctly. Unfortunately:

The CIO of a global company was trying to improve the productivity of his developers, who had to work on a number of separate service platforms. After careful thought, he decided agile was the answer to all his concerns and set about creating an environment in which agile would thrive. This included redesigning office spaces, furniture and equipment for the agile teams, developing a reference web site with guidance on good practice, behavioural training and setting up a network of coaches to help each team adopt and use the methods correctly. It was all well thought through, properly funded and done correctly. Unfortunately:

- as part of the communication he asserted, “From now on, traditional project management is dead and all projects will now be run using agile.” The construction and infrastructure project teams were bemused and joked: “It’s all very well for the IT mob, but you can’t design and build a building infrastructure iteratively; once the foundations are in, you are stuck with them”;

- customers wanted to get what they had contracted to get and did not like the idea of signing a contract for a fixed sum with scope being flexible.

Thus, a great intention failed to get the traction needed to succeed. In the first instance, the CIO only considered the type of work which was his immediate concern, in his silo of the business, namely software. In the second instance, he failed to consider the wider stakeholders who were essential to success. This included both internal and “real” customers, who also had to play an active and continuous role in agile delivery as the “agile customer”.

- If he had framed his initiative as agile delivery, the first problem would not have happened.

- If he had taken a “whole project” perspective and defined who would undertake each role agile delivery required, he could have ensured buy-in from the internal “customer”.

Whether he could have addressed the external customer is a moot point; contracts relying on agile do exist but rely on trust; not many contract lawyers will bet their jobs solely on that.

The lessons taught us that there is no “fast track”. If there were, it would become the usual approach (see lesson 2 in Chapter 2). “Agile” or “Rapid” are development methods or techniques to enable you to develop your deliverables faster within the overall project framework. A correctly designed and applied staged framework should not slow any projects down, unless they need to be.

The lessons taught us that there is no “fast track” . If there were, it would become the usual approach.

Figure 13.7 Concurrent engineering

The top diagram shows the “over the wall” approach, in which each department works on its own aspects in isolation. When they are finished, the work passes on to the next department. The lower diagram shows a concurrent engineering approach, in which the various departments work on all aspects of the product together. This can easily be mapped to the project framework.

Agile techniques should be used when they suit the particular circumstances. If you use them merely because you are “in a hurry,” you risk reducing your project to chaos, i.e. it will become “rabid” rather than rapid!

Concurrent engineering

Concurrent engineering, also known as simultaneous engineering, is a method of designing and developing products in which the different development steps run simultaneously rather than consecutively (see Figure 13.7 above). It decreases product development time and hence the time to market, leading to improved productivity and reduced costs. The approach was developed in the late 1980s with the aim of improving the prevailing “over-the-wall” approach in which the various departments work, in isolation, on their part of the development before handing off to the next department to work on. The over-the-wall method resulted in a large number of unresolved issues being built up as time progressed making the final period before launching the product very lengthy, expensive, and fraught. By contrast, in concurrent engineering the number of issues reduces as time progresses as all interested parties are able to work together to resolve them as the project progresses.

The concurrent engineering approach is wholly compatible with the project management approach in The Project Workout, which also advocates cross-team working and progressing, in stages, to a final solution. Concurrent engineering is also compatible with “system engineering” approaches, which also advocate a multi-disciplinary approach. The only differences are likely to be in the terminology used.

A common mistake many people make when considering how to align engineering approaches and project management is to confuse project life cycles and engineering processes. In the beginning there were sequential development processes, which we now know as waterfall or “over the wall”. When project management was applied, the names of each process activity became the names of the project stages. It was a simple and obvious one-to-one mapping; for example, the “design” process activity became the “Design Stage”; the test activity became the “Test Stage”. When, however, concurrency emerged and processes became iterative, as in agile, concurrent engineering and system engineering, people stuck to the familiar life cycle stages and invented a plethora of spiral, circular, and curvy diagrams to show the iteration and concurrent working. Unfortunately, projects are driven by the immutable laws of physics and “time” and so we cannot go back in time and rework yesterday what we did wrong yesterday; we need to rework today, what we did wrong yesterday. Processes, however, are logical and iterative and not bound by time, but happen in time. In other words, processes can be cycled through as many times as you need during any period of time, such as in a project stage.

If you make this distinction between process and stage, you’ll find the project to process relationship easier to understand. There are, however, a number of definitions in the public domain which use “process” and “stage” interchangeably thus adding to the confusion. During my international work I even came across project life cycles which were deemed to be “logical” and not time bound . . . in other works, what was being talked about was a process and not a project life cycle which could be mapped to a Gantt chart.

Projects which impact a lot of people - the two stage trial

People are central to everything we do and the more you try to change an organization, the more people you need to engage as stakeholders, and move them towards behaving in a way you would like them to. Let’s keep this grounded and consider a major change in a hypothetical company, such as putting in place a new procurement system. The business objective is to reduce the costs of procurement by reducing the number of procurement managers and enabling business managers to initiate and manage this for themselves. Naturally, such a complex initiative requires thorough investigation and, even then, it may be uncertain as to how it will work in practice with the full range of scenarios it has to cater for. There is a trial stage in the project life cycle to cover this risk. Whilst testing will verify the system has been built and configured as per the design, the trial will validate that it was the right design in the first place. Trials of this type are often undertaken using a selected group of users who are monitored by the developers to see how they use the system. The intention is to make sure the system’s functionality covers the full extent of the goods and services needed, both in terms of selecting suppliers and gaining approval for the spend. The system can then be re-tuned depending on the findings of the trial. Unfortunately, even this won’t guarantee the system will meet the needs of the whole organization. Users selected for trials often have a degree of knowledge and aptitude greater than that of the overall user base. Even if this is not the case, as the trial is monitored, the users have a higher level of access to help than is normally the case, often being personally coached in using the system. Users are often more aware of what they are doing/expected to do, as they are briefed and are being watched. Finally, as the trial only covers a small proportion of users, the response time shouldn’t be a problem. Such a trial is usually adequate for making sure the system has the required features, but not necessarily that it can be used by everyone who needs to, or that it is usable in terms of performance. For this reason, where risks are considered high enough, it may be better to have two parts to the trial or even two trial stages:

- the first looks at whether the system has the right features for the job;

- the second looks at whether the use of the system is scalable, bearing in mind the range of users with different abilities and needs, as well as the impact on system performance of a large user base.

There are other approaches you can take to reduce risks, for example, building the system using agile methods, releasing it for specific types of procurement and then, in each release, adding more features. You would, however, still need to consider the form of your trials, depending on the extent of user involvement in the development. Agile delivery merely delivers working code to an operational environment, which may be for a trial or full-scale operations. For this reason, you need to design your overall project life cycle to ensure it helps you manage the risks associated with the project and is compatible with the delivering methods used within the project.

![]() Moving the costs around

Moving the costs around

Have you noticed the trend for management “self-service”, where the corporate functions, like HR and finance load more work on the general managers, justifying it with reductions of costs in their own departments? How often do you think they consider the cumulative impact on the managers of having to do more and more for themselves? Do they actually check the managers have the time? Do they ensure the managers have the right skills and experience to do the job themselves? If they don’t consider these aspects then, despite their being able to show a reduction in their headcount and budget, the company as whole may actually perform worse. They have simply moved a visible overhead cost into the front line where it becomes invisible. By taking a holistic, benefits-led, project managed approach, such issues can be exposed and explored, resulting in a solution that is best for the whole organization, not just one department.

Big stuff, or projects, subprojects and work packages

Defining the scope and boundaries of a project is often problematic. The term “project,” like its cousin “programme,” is often used so loosely that it has very little meaning. Research at the University of Oxford in 2015 found that the two terms are used by senior managers interchangeably. Bearing in mind that organizations have run for decades with no concept of “programmes” as we now define them, the loose use of the terms is not surprising. We just need to be aware that what one person calls a project, another might call a programme.

Nine times out of ten it doesn’t matter what you call things as long as you are consistent but, if you are to understand business projects fully, you need to be able to see the distinction. It might be that the configuration of your support systems will determine the terminology you use.

If you are to have clarity of communication regarding your project, you must decide on the definitions which suit you best and stick to them.

A project, in a business environment, is:

- a finite piece of work (it has a beginning and an end) undertaken in stages;

- within defined cost and time constraints;

- directed at achieving a stated business benefit.

In other words, the key elements of benefit, scope, time and cost are all present. The only place where all this is recorded is in the business case, which serves as the key document for approving and authorizing the project in initial form at the detailed investigation gate and in full at the development gate. As a working assumption, therefore, we can say a project is only a project if it has a business case. Business cases are attached to business projects!

It, therefore, follows that . . . any piece of work, which is finite, time and cost constrained but does not realize business benefit, is not in fact a business project. It may be managed using project techniques, or it may be a subproject or work package within a project. On its own, however, it has no direct value. Only when combined with other elements of work does it have any value. For this reason, you need to consider carefully how to handle what are often called “enabling projects”. Enabling projects are undertaken to create a capability or platform which a later project will use as part of the solution. Enabling projects do not create any value on their own and cannot have a business case, merely a cost. For this reason, enabling projects cannot be “stand-alone” but must be considered as part of a wider business project. They can be treated as work packages or as a subproject.

Any piece of work, which is finite, time and cost constrained but does not deliver business benefit, is not a business project. It may be managed using project techniques or it may be a subproject or work package within a project.

In any project, the project manager delegates accountability for parts of the work to members of the core team. This is done by breaking up the project into work packages, usually centred on deliverables. Each work package has a person accountable for it. This work package can be decomposed again and again, down to activity or task level. This structure is called a “work breakdown structure” (WBS) and is a fundamental control tool for a project.

The first level of the breakdown structure is the project itself. The second level comprises the life cycle stages (initial investigation, detailed investigation, etc.). Below this are the more detailed work packages which, in turn, comprise more work packages and, ultimately, activities.

The top diagram in Figure 13.8 shows this: the development and test stage comprises three work packages (XX, YY and ZZ). Of these, package YY is divided into three more packages (Y1, Y2 and Y3). The whole structure of the project flows logically from project to stage to work package and ultimately to activity. Each work package has its own defined time, cost, scope, and person accountable. It will not have its own discrete benefit. This is the way to structure your projects. It provides good control as no part of the project can proceed into the next stage without all preconditions being met.

The bottom diagram in Figure 13.8 shows an alternative structure for exactly the same project. In this case, however, the project manager has chosen to treat work YY as a subproject. In other words, it has a single identifiable work package, which is itself divided into stages and then into the lower-level work packages (Y1, Y2 and Y3). The remainder of the project is dealt with in the preferred way. It is a more complex structure for the same work scope and so there are risks in using it:

Figure 13.8 Explaining work packages and subprojects

The top diagram shows a project divided into the five stages of the project framework. Each stage can then be divided into a number of work packages (e.g. C is divided into XX, YY and ZZ). In the bottom diagram the same project has been restructured to have YY managed as a subproject.

- you might have a timing misalignment between subproject YY and the rest of the project as there are two separate life cycles and gating might not be aligned;

- interdependencies between the subprojects and project might be missed as it might be assumed “the other end” is dealing with it.

These risks require a greater level of coordination by the project manager.

From this we are able to define subprojects more exactly:

Subprojects are tightly coupled and tightly aligned parts of a project which are undertaken in stages.

The conditions under which you would choose to set up subprojects depend on the degree of delegation you want to effect – it is akin to subcontracting the work. You find this type of structure happens as a result of systems and process limitations or reporting requirements. It may be more convenient to represent and report a completely delegated piece of work as a subproject as it may relate to work which has been let externally, under a contract or internal agreement. Many companies treat their internal software development in this way, hence the common use of the terms “business project” and “IT project”. Such companies generally have no enterprise-wide project accounting capability and hence give the development budget to the IT department at the start of the year, which it then spends on IT projects until the money runs out, whilst the other departments involved have to absorb their costs into their day-to-day budgets. Such an approach is not “wrong” but it can be managed better. When projects become fragmented across an organization in this way, they can become unmanageable and the reasons for doing them can be lost. I have even seen organizations where each department writes their own business case for their part of the project and that part of the project goes through a departmental form of gating. No wonder so much corporate money and time is wasted on projects which are never completed. If you are a project sponsor or manager of a project in such circumstances, my advice is to try and get it managed as one business project, with one life cycle and one business case, but, if not, then make sure your project structure, accountabilities and interdependencies are clear, cover the whole scope and justify it in a single business case. It will be slightly more work, but sometimes it is necessary to flex your approach to fit the host organization, its culture and level of maturity.

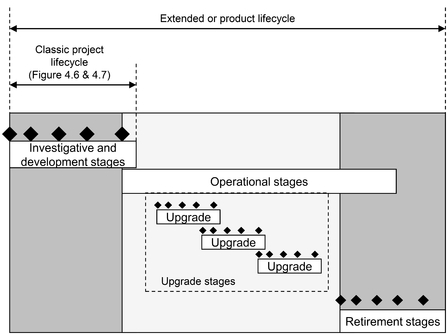

The extended project life cycle

Many projects are undertaken not only to create products, services or capabilities, but also to operate the outcomes of the project. For example, a contractor may not only build a road, but also maintain it throughout its useful life. In such situations, the classic project life cycle, described in Chapter 4, is extended to cover the full operation of the service (sometimes this is referred to as a product life cycle as shown in Figure 13.9), as opposed just an initial operational period. Here, the stages of the project may cover:

- the investigative and development stages: a new capability is developed using a project as the delivery vehicle, taking into account the “whole life” needs of the organization, with respect to the use of the outputs, cost of creation and cost of operation. The last stage of the project (release stage) should overlap the early operation of the new capability in order to facilitate knowledge transfer and to be able to react to any operational issues uncovered. In a contracting situation, this is often defined in the contract (for example in construction’s “Maintenance Period”);

- the operational stages: the capability is used and minor upgrades are done as work packages;

- upgrade stages: more significant upgrades are undertaken to extend the product life, often using a project as the delivery vehicle;

- retirement or withdrawal stages: the capability is withdrawn, retired or de-commissioned when it is no longer needed. This is often complex and also requires a project approach.

Figure 13.9 The extended project life cycle

The project framework in Chapter 4 can be extended to include the operation of the outputs, but such situations are usually better treated as a programme if the revisions are too complex to be managed as work packages.

The “extended” or “product life cycle” is being seen more frequently, particularly in government work. Except in the simplest cases, it is taking the project concept too far to treat all the above as a “single project”. It is better to treat such situations as a programme and provide a greater degree of flexibility in how they are directed, managed, and structured. This is looked at in more detail in The Programme and Portfolio Workout.