30

Being a project manager

You should not only adapt your project management approach but also your personal style to match the culture and other people’s knowledge and capabilities.

“Learn from the mistakes of others, you’ll never live long enough to make them all yourself”

RALPHWALDO EMERSON

Keep your business objective in mind

This book has covered a lot of ground, giving you not only the essential techniques for managing a successful project but also stressing the importance of how you act as a manager. Being “right” in the wrong way is seldom a good means of making progress. I have also emphasized the importance of focusing on the business objectives; the reason why a project is being undertaken. Project management is simply a means of organizing a team to achieve those objectives, not an objective in its own right. That said, consistent, best practice does enhance the chances of success. You don’t have to make every mistake yourself. This why very large projects and organizations develop their own project management methods and train people in their use. If you do not define something, you cannot expect consistency in approach nor expect performance to improve. Instead, success will rely on the “hero” who achieves the objectives, despite the organization, not because of it and that type of success is not reproducible.

If your project budget can accommodate it and the project is likely to last a long time, it’s worth developing your own method. This will enable the project team to become accustomed to a consistent way of working and new members of the team will have a set of good working practices to follow. Further, if you define your method, you can improve on it based on the experience of the team using it. Chapter 31 will give you an outline to help with this.

Justifiably different – tailoring

We are all different

You may have wondered, as you read this book, whether the implied “one size fits all” approach is practical. Can you really direct and manage a small internal project using the same approach as you would for a major multi-million dollar endeavour? Can you take another company’s method and use it on your project? Can you simply adopt an off-the-shelf method, such as those discussed in Appendix C, to use on your project? Common sense tells you this cannot be right . . . and usually common sense is right! All projects are different and you need to take account of that . . . but still keep to the principles and lessons from Part I. Before adopting a ready-made method or developing your own methods, whether for a single project or entire organization, this seeming paradox needs to be solved; to do this, you need to understand the concept of “tailoring”.

What is tailoring?

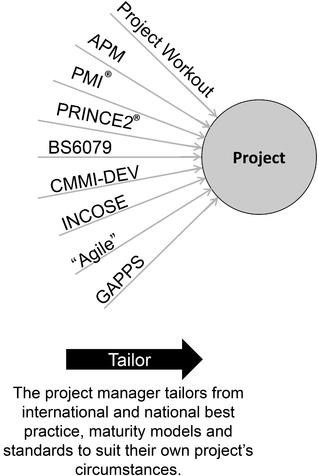

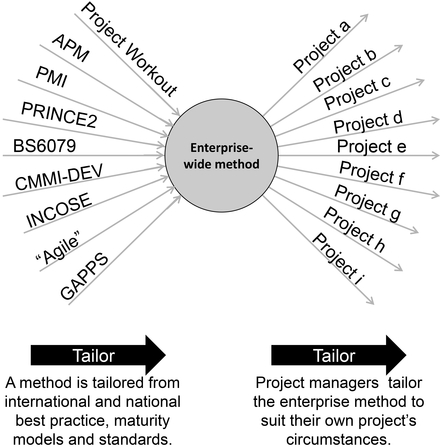

Tailoring enables a project manager to decide how to adapt and use methods and standards for a particular project (Figure 30.1). Tailoring is also used to create an enterprisewide project method, where the owner of the method decides how to adapt methods and standards to create an enterprise method, suited to the business (Figure 30.2). This is dealt with in The Programme and Portfolio Workout.

Figure 30.1 Tailoring for a single project

The project manager creates the management approach for their project, drawing on a range of different sources and adapting them to suit the project and team.

As an example, Chapter 13 describes how to tailor the standard project framework from Chapter 4 to suit different types of project. Similarly, any aspect of any topic in this book can be tailored. For example, you will decide on your project framework, the design of your risk matrix and log and who will authorize the project at the start of each stage.

Figure 30.2 Tailoring for an enterprise-wide method

To create an enterprise-wide project management method, draw from a range of standards, methods, and models to create a corporate method. The organization’s project managers and teams then use this corporate method, tailoring it to suit their particular project’s needs.

Tailoring is not a “licence” to do whatever you want, nor is it a matter of personal preference. Consistency makes life easier for everyone and consistent methods should be used whenever consistency adds value. You need to stay true to the lessons and principles in Part I.

Tailoring takes time and costs money; a project manager should only tailor a standard method, whether corporate or proprietary (like PRINCE2®) when the difference adds value. Remember, any local tailoring must be defined and maintained and this adds more overheads.

Tailoring is not for dummies

Project management is more of an art than a science. Like any management discipline, it requires a mix of soft and hard skills, coupled with sound experience. This is why good professional qualifications don’t just test knowledge but also look at the experience of the individual and how they apply that knowledge. Tailoring is fundamentally about dealing with a project in a specific context not foreseen by a prescribed standard or method. As such, it is a way of dealing with the unpredictable and cannot be defined in a code or strict set of rules. As a result, effective tailoring requires a certain amount of knowledge and experience. A novice is hardly likely to have the breadth of experience to tailor effectively. On the other hand, you don’t need to have experienced everything to be able to make sound judgements regarding how to tailor a project management approach; you should have experienced enough to be able to understand the different approaches others have taken as presented in proprietary methods, standards, text books, case studies, papers and at conferences.

Don’t forget the people!

Be adaptable

Projects are undertaken by people and how you manage a project must take into account the members of the team as well as the stakeholders. Chapter 15 focused on the most appropriate ways of managing the project team and Chapter 26 looked at engaging stakeholders. You should not only adapt your project management approach but also your personal style to match the culture and other people’s knowledge and capabilities. As different people will be at different levels of skill and knowledge, always talk and write in plain language, avoiding acronyms and jargon; this is especially true when dealing with the sponsor and senior stakeholders. Be realistic regarding how much “project management” they can handle before they switch off. How the project is managed is irrelevant to many stakeholders, even though you may know how important it is. If that person is not blocking progress or undermining governance then it doesn’t matter. Above all, how you manage must reflect your values and ethics or you will risk putting yourself under an intolerable level of stress.

Manage up as well as down

Whether you are a team manager, project manager, or project sponsor, you will be accountable to someone (see Figure 30.3). As shown in Chapter 16 on governance, this chain of accountability continues right to the top of the organization. The effective running of a project relies on this chain and from time to time you will need clarification, decisions, direction, or advice from your boss. How do you influence your boss? Before we go into the detail, remember, as a manager, you are also a “boss” and the people reporting to you may have the same frustrations and challenges you have . . . or even worse!

Figure 30.3 Managing upwards

No matter what role you have, you will always need to “manage up“, both in terms of the project organization and other stakeholders, such as line managers, external consultants and internal subject matter experts.

Let’s look at this from the perspective of the project manager. Firstly, remember the project belongs to the project sponsor; he or she owns the business case and is the primary risk taker. You need to understand their priorities; the project is probably just one of a number of topics they are dealing with. You need to respect their time, use it wisely by being clear on any requests you make; don’t waste their time by escalating issues you should deal with yourself. Don’t jump decisions on them at short notice or you may be seen as forcing them into a corner; give as much notice as you can and, where appropriate, provide options.

Try to build up a consistent way of working together, establishing ground rules like agreeing times of the day or week they do not want to be disturbed, when to approach them directly and when to go via a personal assistant. Find out how they would prefer to be kept updated on the project and as you get further through the project check if this is still appropriate.

Trust is at the heart of any relationship, whether on a project, in line management or in your personal life. Admit any mistakes you make, don’t lie or hide information in the vain hope you can bury it, and follow through on your commitments. Any commitments you make should be authentic. By this, I mean when you make a commitment, you fully intend to carry it out. Authenticity, however, also means that if you find you cannot meet a commitment, you should say so and agree an alternative approach. No one likes bad news, so don’t sit on it and then offload it at the last minute, as in the “green-green-green-green-RED” scenario in Chapter 18. Part of maintaining trust is avoiding gossip and inappropriate personal commitments; if you criticize others in a disrespectful way, then your boss may wonder what you say about him to other people. Always stick to facts, filling in the gaps with considered assumptions, if necessary. The old saying “be tough on the problem, not on the people” is as valid today as ever.

Dealing with rumours and gossip

There will always be gossip in your team and amongst stakeholders. Do not ignore it, but do not add to it either! Rumours can damage people’s reputations and threaten the success of a project by undermining confidence in the sponsor, manager, and team or in what is trying to be achieved. If there is gossip associated with your project, find the source. Sometimes rumours start from facts which are inadvertently (or maliciously) distorted, especially in a political context. Talk to people directly asking where they heard this and correct their perception if necessary. If there is a germ of truth in the rumour, this should be exposed before dealing with any problem so that you can respond with facts rather than emotions. You may also need to find additional information from alternative, trustworthy sources. Do your homework discretely; perhaps there is a need for improved communications, a change of approach on the project or some unforeseen consequence of the project which might have been overlooked.

Each project is an opportunity to learn

If you work in project management, it is unlikely that you will work on just one project. Most people are first exposed to project management as a specialist within a project team, working on a work package, reporting to a team manager. As you progress, you will become the team manager and accountable for one or more work packages. This is when you really need to understand the basic project management techniques of planning, reporting, risk management, issue management, and change control. A good project manager will act as a coach, to ensure the project team is working together in a consistent way. At some point, you may start to have more of an interest in project management than in the specialism you started your career pursuing and will look for a project manager role. For some organizations, promotion to being a project manager is part of normal progression. This can lead to discussions on the “right career path”; should a person be rewarded for specialist knowledge by promoting them to a management role where they no longer practice their specialism? It sounds a bit odd. Alternative paths are that the “project manager” manages a project based on their core expertise and they undertake not only a management role but a specialist role. This is why project management is often wrongly perceived by people as a “technical” discipline, primarily for engineers.

Regardless of how you first came into project management, you should treat each project as a personal learning experience so that at the end of it you have grown in understanding and confidence, able to take on more complex work, should you choose to do so. Look at the various standards and at the competencies you need and try to gain experience in as many as you can, as fast as you can.

If you are a project manager, put in place a “lessons learned” approach on the project. Encourage your team managers to share lessons as the project proceeds. Make this continuous; don’t wait until the end of the project and the more formal “lessons learned review”. Act on any improvements suggested and explain why some suggestions are not adopted. This can be run formally, with lessons learned logs being added to when necessary, lessons learned on the agenda at team meetings and reviews at the end of stages and at the end of the project. On the other hand, this can be very informal but just as effective. The golden rule, however, even if not adopting any suggestion, is never to ignore a person who provides feedback; if you ignore them they’ll never bother again. Similarly, accept feedback and suggestions in any form and at any time, whether in the staff café, in the corridor, at a meeting or in the street. Make a note and log the idea yourself; a certain way of being perceived as a bureaucrat is to tell them to enter the feedback into “the system”. Like as not, they won’t bother.

Having received feedback you can then decide if it needs to be acted on and by whom. In my experience, those needing action from outside the project team could prove to be the most difficult to address. For example, most project teams need to buy goods or services as part of the project through the corporate procurement systems. In some organizations, the data required in these systems and the number of sign-offs required by totally uninvolved people is a source of frustration and time slippage. In this case, passing feedback to owners of those systems may help trigger improvements, especially if any other teams express the same opinions.