18

Monitoring, controlling, and reporting

Projects must be, and be seen to be, under control; no one is likely to invest money in an enterprise perceived as poorly managed and out of control.

H F ELLIS

- Only collect information that will be used to control the work.

- Check what you are being told – go and see for yourself.

- Keep reports timely, simple and relevant to the recipient.

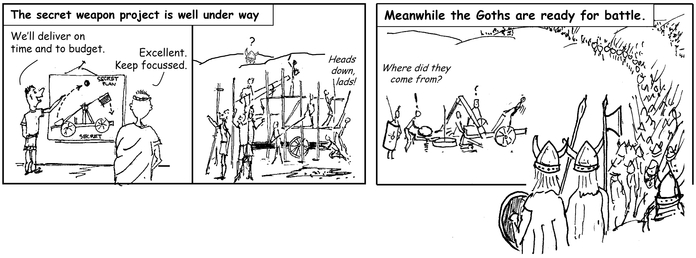

- Don’t forget to monitor what is happening outside the project.

- Act on deviations, once verified – change the plan if needed!

Who, what and when?

Why monitor, control and report?

The aims of monitoring, controlling and reporting are to ensure you know what is happening and give confidence to the sponsor and stakeholders that the project is being managed well. In particular, you should:

- make sure the project’s business objectives are still likely to be met;

- ensure important milestones are met;

- control the allocation and use of resources and funds;

- manage threats to the project’s benefits, schedule, cost, resources and deliverables;

- identify opportunities to reduce the cost and timescales or increase the benefits;

- control changes to the project.

Projects must be, and be seen to be, under control; no one is likely to invest money, whether their own or corporate funds, in an enterprise perceived as poorly managed and out of control. Monitoring and control is about making sure the project will be successful or terminating it if it is longer viable. If you can deal with threats, exploit opportunities, minimize costs, reduce the time taken whilst increasing the quality of the delivered product or service, you are more likely to achieve your objectives.

Monitoring and control is also about setting realistic expectations of project performance. Projects do not always go well, even with the best sponsor, project manager, and project team. By having an effective monitoring, control, and reporting regime, you should be able to spot any problems and alert the right stakeholders.

- Monitoring project work involves measuring and comparing achievement against the plan.

- Controlling is about taking proactive corrective and preventative actions to rectify deviations from the plan and to respond to changes in the project’s context. Such measures should be forward looking, keeping the work on course to meet the business objectives, whilst taking advantage of beneficial changes and reducing the effect of negative changes.

- Reporting lets those who need to know what is happening and likely to happen, so that they can take the appropriate action.

Figure 18.1 shows the key aspects of monitoring, control and reporting in relation to the project control cycle.

Who monitors, controls, and reports?

Figure 18.1 Monitoring, control, and reporting

The control cycle is at the heart of monitoring, controlling and reporting and is used to make sure the project is on track to deliver the outcomes needed. Project work, however, is not the only focus, as it is essential to ensure the project still makes sense in the context of what else is happening in the organization and in the external environment within which the organization operates.

Monitoring, control and reporting should be done at all levels in a project, using the work breakdown structure as the key; Chapter 16 (Governance) looked at this. Monitoring, controlling, and reporting is undertaken by the project sponsor, project manager, and team managers. The aspects monitored are the same no matter the position in the hierarchy of a person but the focus and degree of detail tends to increase at lower levels in the work breakdown structure. A sponsor should be focused on the project’s external context and expected benefits, whilst a team manager will be concerned with the outputs or outcomes they are accountable for.

Not all activities need the same level of monitoring and control; concentrate on those activities which:

- are on the critical paths (but remember that critical paths can change);

- other project teams depend on;

- are due to start soon;

- cost a lot;

- take a long time (but try to split them into shorter activities);

- are diffi cult to measure progress on;

- are uncertain, in terms of output, timescale, or cost.

Each manager is responsible for setting up, in agreement with the higher-level manager, a way of monitoring the progress against the baselined plan. Their specific responsibilities include:

- identifying and solving problems before they affect the work and its outcomes;

- identifying opportunities for improvement;

- reporting progress;

- adding the results of decisions to the plans and telling their team members about the revised plans.

The project manager should design the most appropriate approach and agree this with the project sponsor. Having set the direction needed for monitoring the project as a whole, the project manager should ensure the team managers understand and agree with the approach. It is important to have “just enough” reporting for each person’s need, balancing the effort taken with the value of the information obtained. This is easy to say but may take some trial and error to achieve.

What is monitored, controlled and reported on?

Having a baselined plan is fundamental to effective monitoring and control. Without a baseline, words such as “late”, “early”, “under-spent” have no meaning.

Having established this, important facets of the plan to monitor and control are:

- actual progress toward realizing your benefits;

- risks and issues;

- progress of any change requests;

- timescale, costs, and the resources needed;

- quality of the deliverables;

- robustness of the outcomes;

- benefits (expected and actual) against the business case;

- upstream external work (inter dependencies);

- outside influences.

Don ’t ignore this last point; because a project’s context is always changing, the project sponsor should continually update the project manager with their view on how this context is evolving and the way this may affect the project’s aims and how it is run. This will include what else is happening within the organization, as well as in the wider external context of that organization, in terms of political, economic, and competitive forces. This is why it is vital for a project sponsor and project manager to have an ongoing dialogue and positive relationship. A project manager is far more useful to a sponsor if they are seen as a junior partner rather than a subordinate. The more the project manager understands about the business context the project is delivering into, the better they can undertake their role.

Each of the chapters in Part III focuses on an aspect of project management and describes how each is achieved in terms of approach, techniques, and tools.

Monitoring and controlling specialist work

The heart of a project, however, is not its management; it is the specialist work which is undertaken and this varies depending on the type of project. A project is likely to involve many disciplines, each of which contributes to the overall solution. For example:

- system engineers to ensure every aspect of the overall solution will work as whole, fulfilling the business need;

- software specialists to produce applications;

- infrastructure specialists to design the hardware and equipment needed for the users of the application;

- building specialists to design and construct the facilities needed to house equipment and provide a working environment for the staff;

- training specialists to recommend how best to educate people in the use of the applications;

- change management specialists to determine how best to manage the resulting organization changes;

- communications specialists to deal with external stakeholders.

Each project’s scope will be different, and different people will be part of the team, and how progress and the quality of the specialist deliverables are assessed will differ. If the work is able to be seen physically, as in construction, you can actually see the deliverables growing and measure progress against drawings and volumes of material used. If the work is invisible or less tangible, however, as in software development or business change, progress may not be so obvious. Each discipline will have its own ways of measuring progress and quality and it is essential you understand the approaches and metrics to build these into your control regime. Don’t be afraid to challenge any such methods and don’t take anything for granted until you are confident the approaches used by the specialist teams are sound and telling the right story. Seek alternative views from other specialists in the same discipline if necessary.

When to monitor, control and report

Monitoring, control, and reporting should begin as soon as the project starts. Even in the early part of the first project stage, when no baselined plans are available, you need to have a feel for how things are going. Having your own “plan for developing the plan” is useful, as you can set expectations and a start promoting a sense of discipline, rather than letting the work drift.

When you have finished the plan to the required level of detail and the “doing” starts, whether further investigative work or actual development, the rate of activity and, consequently, the rate of spending will increase. A fully effective monitoring and control regime must be in place before this really ramps up. Plans need to be prepared to reflect the monitoring regime to be used. For example, if agile delivery techniques are used, a plan takes a different form to one where the scope is fixed.

Different levels in a project and different types of work require different frequencies of reporting, as shown in the control cycle in Figure 18.1. The appropriate frequency for the cycle depends on the nature of the project, its stage of development and inherent risk. Completion of activities is evidence of progress but not sufficient to predict milestones will continue to be met. The manager should be continually checking that the plan is still fit for purpose and likely to realize the business benefits on time; the future is more important than the past as that is what you are trying to influence.

Often the control frequency is driven by regular reporting calendars set organizationally, but at other times, reporting may need to be “ad-hoc”, such as for high-priority issues and exception reporting. For regular reporting, the frequency may range from daily, which is used in agile techniques and also the roll-out or provisioning of some services to quarterly, as for some high-level boards. Reporting frequency is usually driven by:

- the stakeholders’ actual or perceived needs for information;

- the sponsor or project manager’s actual or perceived needs to stay informed and their assessment of risk;

- organizational practice set, say, by a programme management office or other overseeing body.

The frequency of the control cycle can change through the life of a project and need not be consistent across a project. For instance, daily or weekly reporting on one work package may be necessary, whist two-weekly on others may be adequate.

![]() Making reporting more convenient – getting the timing right

Making reporting more convenient – getting the timing right

A large organization, which operated across the world, had the practice of requiring the project manager for each of over 2,000 projects to report on the project in a central system by 5 pm, every Friday, UK time. The assumption was, to be useful, all project reports had to be synchronized or there may be mismatches. Being an international organization meant staff in the Middle East were having their weekend break and staff in the Americas were either still in bed or just starting the working day. Staff in the Far East had just woken up to the start of their weekend. The reporting time did not fit global working patterns and time zone and so relaxations were allowed. That left, however, a large number of people in the UK and Europe still having to submit their reports right at the end of the week and all at the same time. The information systems, mostly unused throughout the week, suddenly had to take on peak load for just one hour every week. Consequently, people were often locked out of the system and had to wait into the evening to submit their reports. In most cases, nobody looked at the reports until they returned to work after the weekend. The attitude to reporting was starting to degrade into being mere “lip service” with the quality of the reports suffering as a result.

The company solved this problem by challenging their own assumption that reporting needed to be synchronized. They had already delinked reporting from the “due time” everywhere outside Europe and then asked themselves, why not do this for every project, everywhere? This is exactly what they did. They allowed each project manager to decide when it was best to report on their project (in agreement with the sponsor or, if in a programme, programme manager), simply insisting that at any point in time no project report should be more than eight days old. They even allowed people to change when they reported and encouraged major issues to be reported as soon as they arose.

Overall control was kept as the central management office ran a report every week listing any project outside the eight-day window (there were very few). This approach was like a breath of fresh air. Reporting quality improved and those people involved could make best use of their time . . . and the information systems people didn’t have to upgrade the performance of their servers to deal with the peak load.

Making reporting work for you

How formal should reporting be?

The level of formality for reporting should reflect the project or work package being reported on and risks associated it. You also need to take into account the capabilities of the people you are asking to provide the reports. Reporting is often looked at as a bureaucratic overhead and as a result the quality of reports can suffer. Review and approval of a report may be undertaken informally where a reporting error would not pose a major risk and may be done as part of normal day-to-day management, in which case a manager may approve their own reports. The exception to this is for reports which are being sent outside the organization, say to a customer, when commercial oversight would be prudent so as to avoid accidental commitments or compromising the contract.

Analysing the information from reports that you receive

Analysing the progress information and using forecasting techniques will give you some idea of the likely future cost, timescale and quality of deliverables. How far you can go with analysing and forecasting depends on the type and scale of the project. Earned value management techniques will give you a valuable insight into performance on the schedule and the cost. The techniques also give indicators to help you forecast any remaining work and expenditure. It is, however, a technique that requires good information flow, which many organizations simply do not have. See Chapter 22 for more on earned value management.

You should check carefully forecasts provided by suppliers or team managers to make sure they are realistic. An activity which has been consistently behind schedule is unlikely to completed on time without affecting costs or the quality of project deliverables. Remember, the last 20 per cent can take as long as the first 80 per cent. Don’t just rely on the formal reports you are given, whether submitted in writing or verbally at meetings. Where possible, look for yourself; get into the habit of walking about and being approachable; often people will tell you things they are reluctant to put in writing if they meet you informally.

Sending your reports out

When you have finished the analysis, you must then tell the right people about the current state of the project and the likely outcome. A set of well-thought-out reports meeting the needs of the various stakeholders will make this much easier.

Most sponsors and customers insist on regular reports and you should agree the style, content, and timing of these reports when the project is being set up; as the project progresses, continue to check that what you agreed is still valid. The reports should be brief and assure the recipients that objectives are being met and benefits will be achieved. Where necessary, you should say what action you have taken to put any problem area back under control.

Timeliness of reports is also essential. Generally a report which is “approximately right” now is preferable to one which is perfect but three weeks old. Sometimes this can be diffi cult to balance, especially when reporting to customers as there may be unforeseen commercial implications of a report which is “mostly right”. Further, some people take delight in finding faults and errors and can sour what could be good working relationships.

![]() “Cleaning up” report to look good

“Cleaning up” report to look good

The practice in one organization was for the line managers of project managers to review the project reports before they were sent out. Similarly, the line managers of the specialist team managers also reviewed their reports. They argued that as these people were their staff, they, as line managers, were accountable for the quality of the work and it was essential they review all reports and amend them if necessary. This not only took time, often days, but also led to the reports being diluted. No line manager wanted to declare that things may not be going so well in their department. The line managers’ line managers took the same view and also wanted to review what was being said. The project managers became frustrated as their reports were often changed, hiding uncomfortable truths, and the project sponsors and stakeholders were annoyed at having to wait so long to actually receive a report. They started to realize the report sometimes omitted important information. Projects seemed to stay on “green” status for months and then suddenly turn “red” just before they were due to deliver.

The chief executive of the company was very keen on “flat structures” to speed up information flow around the company, so he sanctioned a radical change to reporting. Under the new regime, a project manager, no matter at what level in the organization, submitted his or her report via a new centralized system directly, with no review by their line manager. The report was available to the project sponsor and line manager at the same time immediately it was submitted. This speeded up information flow dramatically. It also improved the quality of reports. Through coaching and experience, as well as seeing everyone else’s reports, the project managers learnt to write more accurately and concisely, keeping the reports to facts and recommendations and avoiding personalities. It also promoted a direct dialogue between the project sponsors and project managers, building trust and this helped circumvent those line managers who still wanted to exert pressure to make the reports “look good”, rather than tell the truth.

Reporting templates

Chapter 17 gives you an outline for a project report, detailing the most important information. Often enterprise project management methods include a number of templates for reports, which you can use as a starting point to tailor to meet your particular needs. Remember, the focus of reporting may change over time. For example, requirements metrics may be more important at the start of a project, with testing metrics taking higher attention towards the end, so the report content will need to change. The report should always reflect the way the work is being undertaken; for example, if agile techniques are used, “burn-down charts” are essential. If necessary, develop specific reports for specific target audiences, designed to show particular aspects of the project but do try to minimize the number of reports. The organization in the case study on the timing of reports had just one project report internally with only board level and customer reporting being specially designed. You may not manage to do this, but it’s worth trying.

Finally, don’t assume all reports have to be written. Verbal reporting, say at a team meeting, can be adequate in many cases but the topics covered are likely to be the same as for a written report, so have a standard agenda. The advantage of covering reporting at a meeting, regardless of whether the report is written or not, is that it gives those present an opportunity to query and challenge the report and so adds to the quality of any resulting actions. Face-to-face reporting can also avoid misunderstandings.

Red RAG to a bull!

“RAG” is a simple status reporting method, enabling the reader of a report to grasp very quickly whether a project is likely to achieve its objectives or understand the status of a particular aspect of the report. RAG stands for Red–Amber–Green:

- red means there are significant issues with the project that the project team and project sponsor are unable to address;

- amber means there are problems with the project but the team has them under control;

- green means the project is going well with no significant issues, although it may be late or forecast to overspend.

Different people will define these in different way, but on the whole, they follow the intention given above. Some organizations use “BRAG”, where the “B” is blue and denotes “completed”.

The RAG status works best if based on the project manager’s own assessment of the situation and is useful for highlighting those projects which may have difficulties. Some organizations have the RAG status set automatically by systems, e.g. when a project is forecast to overspend. Such systems often trigger automated notifications or emails to key stakeholders to alert them of the problem. That sounds very logical as reports should be acted upon and if no report is sent, then no action can follow. Unfortunitey, logic isn’t always the best driver on management as the case study shows.

I saw one part of an organization implement an automated “RAG” system and the stakeholders were drowned in notifications, receiving so many that they often missed those that really mattered. Most commonly, a project would be automatically set to “red” if a milestone was forecast to be late. In most cases, the project manager and team were working on solutions and needed no help; this was, after all, why they were there. Alerting the sponsor was unnecessary as they could do nothing at that point in time to help. The automated system was switched off and the overall project status was set manually by the project manager. They did, however, retain the automated flags against the different parts of the report as this helped the project manager spot variance quickly and ensured the current view of “the truth” was not hidden.

Workout 18.1 – Setting up your reporting regime

Workout 18.1 – Setting up your reporting regime

Use the following prompts to help you define your reporting regime:

- Reporting should reflect the information needs of the stakeholders, especially those with responsibilities for some aspect of governance.

- The “weight” of the reporting regime should be appropriate to the work being undertaken and the people undertaking it.

- For customer projects, the reporting regime should protect your commercial position and collateral.

- The basic planning elements should be in place to collect the level and detail of reporting required (for example, if project costs are to be tracked, the cost codes need to be created to capture this).

- A repository should be set up where reports should be available for recipients and archived.

- A permissions structure should be defined for the reporting repository enabling those who need to publish and see reports can do so.

Workout 18.2 – Is your reporting regime working?

Workout 18.2 – Is your reporting regime working?

Use the following prompts to check how well your reporting regime is working:

- Is reporting being undertaken in a timely manner?

- Is the “weight” of the reporting regime appropriate to the work being undertaken?

- Is the level of accuracy of the reports appropriate to the needs of the report recipients and the time allocated for preparing the report?

- Is there evidence that reports are being read and, where necessary, being acted on?

- Is there information known or being discussed which is should have been included on the reports but hasn’t been?

- Is confidentiality being respected in the reports?

If you answered “No” to any of the questions, adjust your reporting regime accordingly; involve the sponsor and your team in getting this right.

Workout 18.3 – Is each report adequate?

Workout 18.3 – Is each report adequate?

Some people are great at writing reports; others aren’t. Unfortunately, the skill of a person in writing a report may not match their skill in their specialist discipline; great technicians may be poor report writers! Use the following prompts to check the quality of each report:

- Is the report focused on the future and likely outcome for the work covered by the report?

- Is the content of the report relevant for the readers of the report?

- Is the style and language used in the report acceptable?

- Is it clear on why the report recipients would want to read what has been written?

- Is it clear what, if any, action is expected as a result of the report?

- Does the report indicate the level of confidence of the manager in any forecasts?

- Are risks and issues worded clearly and unambiguously?

- Do the data on the report match those on any subsidiary reports or data?

The best way to handle a “no” on any of the above is to work with the report author and coach them towards writing succinct and valued-added reports. If you don’t provide any feedback, don’t expect reporting to improve. If you are the author, ask a “peer” to look at it and coach you. This may sound like a lot of time to invest but good information is at the heart of good management and reporting that can be trusted will save far more time than it costs. Don’t be tempted to rewrite reports for people; they will become demoralized and simply stop trying and leave it up to you.

If you cannot achieve a good-quality report from your team managers, start by having verbal updates and write up your report; by doing this with the team, they will understand your needs and may soon find it easier to provide a short report in advance the speed the meeting up.

Don’t ignore what is happening around the project

Copyright © 2016. Robert Buttrick