Chapter 2

Public relations and communications

Chapter Aims

This chapter explores different communication theories and traditions that underpin public relations. It takes a thematic approach looking at the who, what, why and how of communication and grounds the idea of PR firmly in a societal context. As part of this it also looks at the role of the media in communicating to and between organisations and individuals in society. All themes are interconnected and taken together help us understand the complexity of PR. Many of these ideas will be picked up later in this book but for now this chapter aims to provide an overview. It concludes by bringing these ideas together and what they mean to public relations practice.

Background

Communication theory is nothing to be afraid of! Communication is everywhere. As people we communicate all the time through words, sounds and gestures. As communication practitioners it is helpful for us to understand what goes on behind the scenes of the communication process so we can become more effective at what we do and we can use some of the theories explored here to guide our work.

According to Windahl et al. (2009), the definition of communication falls into two categories. The first focuses on communication being a one-way activity with the idea of transmission. Here the concept of Sender–Message–Channel–Receiver model predominates. As Theodorson and Theodorson (1969) suggest, this is transmission of information, ideas, attitudes or emotions from one person or group to another. An example of this is the Shannon and Weaver model of communication that will be explored later.

The other tradition puts mutuality and shared perceptions at the heart of communication and it is a two-way activity. Rogers and Kincaid (1981) define communication more as a process where participants create and share information with one another in order to achieve mutual understanding. In part these different ideas mirror the historical development of communication theory and practice. Early models emerged from mass communication traditions that focused more on the one-way process. Now Rogers (1986) argues that with the rise of digital technology it is becoming difficult to think of sender and receiver but instead each person is a participant.

Communication as a one-way and two-way activity links to the concept of power. Here the idea of power being more balanced in a two-way process is an important one and links to Grunig and Hunt’s (1984) view that only two-way symmetrical communication is excellent. Although slightly simplified, the idea that in two-way communication process power is shared enables the communication to be longer lasting as it has been shaped by all those involved. The concept of power is a key theme that runs through all communication concepts.

The other idea that runs through our discussion of communication relates to the concept of communication levels as suggested by Berger (1995). He puts forward a fourfold classification consisting of: intrapersonal (thoughts); interpersonal (conversations); small group communication; and mass communication. Historically the focus in PR has been on mass communication (the one to many perhaps illustrated by securing editorial in the newspapers). Now the importance of understanding how people think and behave, as well as conversations people have is of growing importance. This connects back to the view that two-way communication is becoming more critical to securing lasting understanding and encouraging people to change behaviours.

The final strand to think about in communication is the idea of mediation: the way information is communicated and transmitted. Unmediated communication is two-way contact that does not pass through a channel, such as a conversation between two people. Mediated communication inserts a channel, such as the media into the transmission process.

Although the idea of theory can be off putting it is liberating and can drive creativity by channelling it more effectively. As Kurt Lewin, one of the leading organisational theorists, once said: ‘There is nothing so practical as a good theory’ (1951: 169). It is a lesson that is still relevant today and of increasing significance to PR. This view is supported by Toth (2006) who argues that we must continue to understand and grow knowledge in the PR field if we are to improve what we do.

Theories of the Organisation and Economy: Why Bother to Communicate?

The idea of systems theory is important to those studying and practising PR. The term was originally developed by Bertalanffy (1968) while reflecting on the interconnectivity of the natural world. The concept was developed by Katz and Kahn (1978) and applied to the organisation, suggesting these are social systems that turn inputs (such as parts and labour) into outputs (things we buy). Organisations are linked to their external environments and are affected by these environments. To survive, organisations must adapt and connect to their environments. Communication plays a critical role in doing this. Grunig and Hunt (1984) argue that communication inside the organisational system and between the organisation and the wider system in which it sits is the only way the organisation can survive. It is the idea of systems on which Grunig and Hunt developed their four models of PR, in particular the importance of two-way symmetrical communication. The four models were explored in Chapter 1.

Communications is often seen as a buffer against or bridge to the environment as suggested by Meznar and Nigh (1995). Here organisations might have to resist, adapt or manipulate the external environment so they can survive. This is supported by the concept of resource dependency theory (RDT) (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978; Kotter 1979) whereby most organisations are dependent on gaining resources in an uncertain environment and want to reduce uncertainty by engaging and communicating with those who take decisions about it. Organisations have to make choices about how they operate in complicated environments that are affected by pressures from government, consumers, interest groups and public opinion. Compliance with expectations of this environment or needing to change these expectations may explain why organisations need to communicate in the first place.

This takes us to ideas around the behaviour theory of the firm and the way organisations take decisions. Simon (1957) suggests that firms tend to seek acceptable rather than optimal decisions, a process known as satisficing. This has been developed by Schuler and Rehbein (1997, 1999) who suggest that based on the firm’s history, structure and experience, it will filter and interpret the external environment and take a view on its communications strategy and engagement with stakeholders.

All of this comes back to the economic imperative of organisational existence. Ultimately economics is about managing costs and, as Williamson (1985) argues, all organisations need to reduce their transaction costs as much as possible. Here a transaction simply means all interactions and interdependencies of the firm as these always have a monetary value associated with them. An understanding of these costs prompts an organisation to engage in the communication with stakeholders.

So it is clear that organisations cannot operate in isolation. Communication is an economic necessity and there are many theories and concepts that help us understand the mechanics of the communication process. If we understand this better then our PR planning – the PR Process we explored in Chapter 1 – can be more effective and we can approach what we do more responsibly because we understand how important PR is to how the organisation and society function.

Mass Communication Theories: Mechanics and Process

Understanding public opinion

A backdrop to communication is the concept of public opinion. PR must be able to identify what people think. Often PR is used to influence organisational publics (or stakeholders) and these people in turn are influenced by wider public opinion. Sometimes PR is used to influence public opinion directly. A simple example of this is the UK government trying to get more people to eat five pieces of fruit or vegetables a day. Sometimes PR is about trying to influence public opinion indirectly by putting pressure on organisational stakeholders to make the case on a particular issue. An example here might be the campaign to stop the introduction of minimum unit alcohol pricing. Here those against a move to increase prices created cases, facts and other supporting evidence and encouraged the media to write articles that were negative to the government proposals. Ultimately, the government changed its mind. Alternatively, PR is simply used to encourage debate on a subject, to test out different ideas and gauge reaction.

Price (1992: 46) citing Childs (1965: 13) argues that opinion is ‘an expression of an attitude with words’. We can think of an attitude as an underlying disposition to think or feel a particular way about something. When that attitude is communicated it becomes an opinion. So public opinion means the communicated attitude of the public, but what does the expression of public opinion mean? Is it the opinion of the majority or just those who choose to communicate it by shouting the loudest?

According to Herbst (1993), there are four views of public opinion. First, the general will, collective view or consensus. This is evidenced through debate and discussion and agreement emerges. Then there is the aggregate view that means it is the view of the majority. This type of public opinion is evidenced through opinion polls and surveys. She also puts forward the idea of the majoritarian view. This takes the aggregated view into account but incorporates the idea that not all opinions are of equal weight. The final concept is reification which assumes public opinion doesn’t exist at all and is a fictional entity.

Yet there are issues with understanding public opinion that PR must be aware of, in particular if it is determining the type of intervention or PR activity that is to be used if public opinion is to be influenced. As L’Etang (2008) points out, public opinion is not static and it changes all the time. Often public opinion is more complicated than simply asking somebody to answer yes or no to a question. You can see this when you analyse media and social media discussions. At the same time, are we always to assume that the majority view is always right? Noelle-Neumann (1991) for example suggested that often minority opinion gets suppressed into a spiral of silence as people become fearful of voicing opinion that is different to the majority. She cites the role of the media in contributing to this silence. So in order to fully understand public opinion, Price (1992) argues a more holistic approach is needed that looks at the focus of opinions, what may have influenced the responses, the context and timings and how strongly the views are held. In other words, public opinion is highly complex and it can easily fool us.

So, how is public opinion influenced and what are the processes that contribute to its formation? Early work on this has tended to come out of research by mass communication theorists and is heavily influenced by the role of the media in this process.

The basic communication model

In 1948 Harold Lasswell came up with a five-point formula to explain the communication process: who says what, to whom, with what effect? This simple statement was heavily influenced by early communication thinkers and had overtones of propaganda, suggesting that all communication is persuasive and must always have an effect.

A year later, Shannon and Weaver (1949) took Laswell’s formula and developed it into a linear flow showing a sender communicating a message to a receiver. The purpose of this linear model was originally to show engineers the technical communication process of using a telephone. Importantly, they introduced the idea of interference in communication, which they termed noise that could occur because of faulty equipment. As a result, the message could be distorted or misunderstood. This idea was rapidly developed by communication theorists and is illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Adaption of the Shannon and Weaver model of communication

Source: Harrison (1995: 30). Used by permission of Thompson Learning

This new model incorporates useful elements for PR. There is a source from where the communication originates. How this source is viewed and how it views its audiences can help or hinder communication. The source or sender selects information and encodes this using words, symbols and images to create a message that will be transmitted by a channel (also known as a medium or platform) to a receiver (also known as a public or stakeholder) who will decode or interpret the message and respond with action or no action that feedbacks to the sender. Most importantly this process takes place against a backdrop of noise, which means anything that gets in the way of the transmission. Today this could be taken to mean everything from the receiver’s physical and mental state to the distraction caused through the receiver’s exposure to lots of other messaging including advertising.

The concept of feedback is important to PR. This provides an opportunity for the sender to modify the message and language used in order to improve understanding if the receiver has misunderstood the communication. The source and receiver are in constant feedback and adjustment – it is a continuous process of checking and adjusting what you are saying to whom and whether it is having the appropriate effect.

There is still an issue with this as the process is linear and one-way. The receiver is not in equal participation with the communication. The sender is still trying to influence and the feedback is about helping the sender influence the receiver better. It is also difficult in this model to fully understand the role of mass media such as TV and newspapers in this process apart from their role as a channel/medium.

Figure 2.2 The Osgood–Schramm model of communication

Source: McQuail and Windahl (1993: 19), Figure 2.2.3. Used by permission of Longman

Here the work of Schramm (1954) is useful (see Figure 2.2). He and Osgood created a circular model that better addresses the idea of communication as a two-way process. They suggest the sender and receiver is engaged in a continuous and active form of communication and message interpretation, arguing that it is misguided to think that communication starts and finishes somewhere and communication should be considered as an endless process of iteration and building understanding.

Building on this idea that communication is an endless process and incorporating the concept of more equal relationships, McLeod and Chaffee (1973) developed their co-orientation models. Critically they identified three relationship types that define and influence interactions between an organisation and a stakeholder. These include the extent to which there is more than one stakeholder; the number of relationships increases in a non-linear way; and the role of inter-stakeholder relationships. All of these make the traditional linear view of communication far more complicated. This work subsequently input into Grunig’s views on two-way communication (Grunig and Hunt 1984) and has been subsequently influenced by it. Here the idea of communication being a relationship is important and links to PR being viewed as a relationship function as suggested by Ledingham (2003).

Mass communication theories

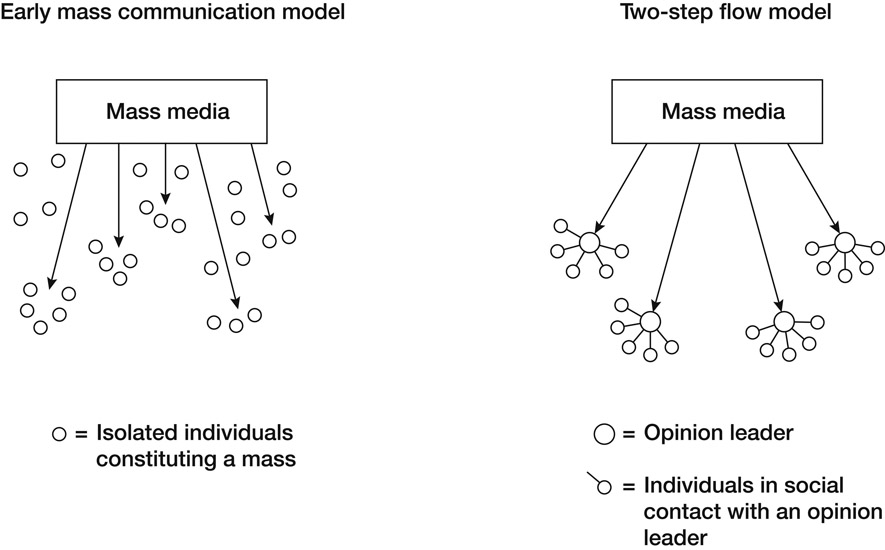

Yet these models still do not fully address the role of mass media in the communication process. How much the media influence their audiences and how persuasive a role they play is much debated. Thinkers from the Frankfurt School, formed by academics escaping from Nazi Germany in the 1930s, feared that mass media would generate mass effects and whoever controlled the media would control the minds of the public. This idea initially evolved to become known as the hypodermic model or magic bullet model. Here it is suggested that audiences are passive and react uniformly to messages received via the media. In other words, the message went simply into someone’s head and was accepted unchanged, suggesting people could be easily persuaded. People were isolated and not affected by others. Subsequently, research conducted during the 1940s and early 1950s showed that this approach over-inflated the power of the media and that people are actually more likely to be influenced by their friends, neighbours or ‘opinion formers’ than the papers they read or the TV they watch. This developed into the two-step flow theory by Katz and Lazerfield (1955) (see Figure 2.3).

The debate around the influence and effect of mass media remains contested. During the 1970s, academics, in particular those known as the Birmingham School led by Richard Hoggart and Stuart Hall, returned to the work of earlier thinkers and looked again at the effect of the media on society. They argued there was evidence to suggest the media support the interests of capitalism with negative images of those less powerful in society. How this then directly affects the individual is less clear. That said, scholars such as McQuail (2010) suggest that in recent years with conflicts such as the two Gulf Wars the media have played a powerful role in influencing public opinion. Perhaps the same too can be said of the War on Terror.

Figure 2.3 The one-step and two-step flow models

Source: McQuail and Windahl (1993: 62), Figure 3.2.1. Used by permission of Longman

Here the idea of Agenda Setting is of relevance. It is based on the simple idea that the mass media contribute to telling people what to think about. In other words, the media help set the public agenda. This can be evidenced in the daily news agenda each morning. Often the same issue dominates the newspaper and TV stories over several weeks only to be replaced by another. How does this happen and who tells the media what to think about?

Another useful way to look at the role of the media is through the ideas of Westley and MacLean (1957) (see Figure 2.4). They focus on the roles in the communication process and in particular they introduce the role of gatekeeper or channel (C) into the communication flow. The key roles are as follows: (A) which is the sender of information. This is the advocate who has the aim of influencing people. In mass communication this can be played by many sources of information including the PR consultant of the organisation. Then there is (C) the channel role, here the medium gives information to the public and acts as a gatekeeper; for example, a journalist selects information from a diverse range of sources. This contributes to setting the news agenda. Then there is (B) which relates to the receiver who has a behaviour role; that is how the they take the message and act upon it.

This process does not operate in isolation as the media also get information from other events (X) that take place. Here the model is not a closed loop. Information and interactions operate in different directions. Journalists may take some information from the PR practitioner but add to this using other sources and events. This model is perhaps more relevant to the concept of traditional media (newspapers, TV news) where the media act as a filter. What is interesting now is the rise of unmediated media and digital sources of information that enable PR practitioners greater contact and interactivity direct with publics and vice versa without the filtering effects of traditional media.

Figure 2.4 The Westley–MacLean model of communication

Source: Windahl et al. (1992: 121), Figure 11.1. Used by permission of Sage

Building on the idea that communication is much more of an interactive process, with a range of external and internal influences on both those sending information and those receiving it, German researcher Gerhard Maletzke (1963) came up with a more sophisticated understanding of the process. Here a social psychological view dominates.

In this approach, greater attention is given to the motivations, environment, culture, personality and wider influences on the sender, channel and receiver. This is illustrated in Figure 2.5. For the PR practitioner, this means taking a much more holistic view of the communication process. Critically, by researching and understanding the targeted publics, more appropriate messages and stories can be created that are more meaningful. The type of words and images used must fit the targeted public’s understanding but in a way that still works for the organisation. External influences too affect how people think and the medium used also can have an influence. If the message appears on the news on TV it may be seen to have more authority than if it appeared on social media. This is why understanding people and wider public opinion is so important.

The shift to putting the audience central to communication also underpins the Uses and Gratification approach by Blumler and Katz (1974). This marked the continued move away from the emphasis on the sender of information to the receiver. Simply it means that audiences generally seek content – reading or watching certain TV programmes, magazines or online material – that seems to be most gratifying to them, based on their individual needs. McQuail et al. (1972) identified these needs as falling into four broad categories: diversion (escaping from reality, routine and problems); personal relationships (companionship and having something to talk about); personal identity (helps an individual shape their own personality); and surveillance (helping an individual find out about the world). A PR practitioner must recognise that people do not wait around to receive messages via different media. A clear understanding of how different media fulfil different needs in people is important to creating effective communication strategies.

An interesting variation of some of these ideas and one that has relevance in an increasingly digital world, is what Windahl et al. (2009) suggest is a network approach. This builds on the ideas of Rogers (1986: 203) who suggests a communication network consists of ‘interconnected individuals who are linked by patterned communication flows’; the focus is on contributing to and building these communication flows. Here there is more equality as people talk across traditional cultural and social boundaries. Key terms to think about in networks are the different types of roles people may play in networks, including straightforward membership of a group or cluster in a network; the liaison role that links the cluster to other clusters; ideas around the star who links to lots of individuals; and the boundary spanner that links the network to the environment (Monge 1987). PR practitioners can use the concept of networks when exploring ways to communicate with and among relevant groups.

Persuasion and Motivation: It is all in the Mind

A key strand running through the ideas above is the concept of persuasion. There are many different definitions but most academics agree that persuasion revolves around the notion of influencing a change in people and communities. Perloff (2010) makes clear that persuasion refers to when there is an active attempt to change a person’s mind. Importantly, the concept of free choice is embedded into this definition – it is about convincing people to change their attitudes and behaviours, not coercing them. As such the idea of persuasion is integral to any debate around communication and links us to the ideas of Grunig and Hunt’s four models (1984) – the two-way asymetrical approach that incorporates the ideas of truthfulness and choice.

The concept of persuasion is also linked to understanding people’s attitudes, beliefs and values. A belief is deeply held and consists of thoughts and feelings that help to create a reference system for understanding our world. Our beliefs are underpinned by values, the ideas that are core and most important to us. For example, an individual might believe that by working together we can all improve our community and this is supported by the value of cooperation. Beliefs are not simple. Rokeach (1960) suggests there are central and peripheral beliefs. Central beliefs are very close to values and peripheral beliefs are more loosely held. It is our beliefs and values that help create our attitudes. Our attitudes are what is witnessed when we react to people and events and according to Allport (1935) act as a filter to help people deal with situations.

There is much debate among social psychologists about how attitudes are formed. These include ideas around class conditioning through stimuli; using rewards and punishments to encourage or discourage behaviours (known as instrumental or operant conditioning); through our direct experiences and watching others (known as social learning theory); and finally there are those who say that it is determined by biology (genetic determinism). So it is unsurprising that social psychologists have come up with a range of ideas about how to change attitudes through the use of persuasion.

Persuasion theories

A summary of key persuasion theories can be found in Table 2.1. It provides a simplified overview of the key approaches and some of the leading thinkers.

Often these ideas help us come up with what might appeal to people and help bring about behaviour change. This sounds a modern concept but persuasion has its origins in Ancient Greece and the work of Aristotle. Jowett and O’Donnell (2012) suggest that it is Aristotle that first developed methods by which persuasion takes place, drawing on four key concepts of pathos, ethos, logos and kiaros. Much of this thinking still permeates the theories above in terms of the type of messaging necessary to bring about attitudinal and behaviour change.

Ethos looks at the appeal to the speaker’s character: the credibility and authority of the speaker seeming knowledgeable, expressing expertise yet perhaps showing some modesty and putting achievements into context; in particular, trying to find common ground to help build trust and not being hypocritical (Leith 2012). Pathos is the appeal to human emotions by conveying arguments and ideas that make the audience feel a particular way. There are a number of figures of speech that help here, including ideas around epistrophe (repetition of the same word) and simile (explicitly comparing two different things). Logos is the appeal to reason and pushes the argument forward and the way the speaker positions ideas. Finally, kiaros looks at timeliness and the importance of the opportune moment to make your point.

Leith (2012) talks of the five cannons of rhetoric that work as a guide for speeches and arguments that together have strong emotional appeal. These include ideas around invention (developing and refining arguments; arrangement (arranging and organising arguments); style (how you present your arguments using figures of

Table 2.1 A summary of some of the main persuasion theories

| Persuasion theory | Key concepts and example |

| Cognitive dissonance Leading figure: Leon Festinger (1957) |

|

| Social judgment theory (SJT) Leading thinkers: Sherif and Hovland (1961); Sherif et al. (1965); Yates et al. (2003) |

|

| Elaboration likelihood model (ELM) Leading thinkers: Petty and Caccioppo (1986); |

|

| Narrative paradigm Leading thinker: Fisher (1984, 1987) |

|

| Theory of reasoned action Leading thinkers: Ajzen and Fishbein (1980); Ajzen (1985) |

|

| Theory of planned behaviour Leading thinkers: Ajzen (1985) |

|

speech and other rhetorical devices); memory (delivering speeches and arguments with passion by not being distracted by reading) and delivery (the tone, gestures of delivery).

More recent work on this comes from the likes of Lilleker (2006) who devised the Five State Process of Designing Rhetorical Communication – identify and define the problem; identify the audience required to solve the problem; identify or infer that audience’s interpretative system and their norms, fears and values; translate the problem into the audience’s interpretive system and create the message; and finally deliver the message for optimal audience acceptance.

Yet people are not all persuaded in the same way and at the same time and some are not persuaded at all. What is helpful to get us to understand this is the work of Rogers (1962) who explains that people go through the same process of accepting or rejecting new information but it happens in different ways. He called this the diffusion of innovations theory. In this context the idea of innovation relates to a new idea or object and diffusion is how this is communicated and adopted by people over time. This is useful as it helps us think about the type of communication to undertake at any given time in this process and to recognise that people may be in different places in this process. There are five stages:

- knowledge – this is when people become aware of something and often this takes the form of a public or consumer campaign to raise awareness; for example, the generation of media interest;

- persuasion – individuals start to form an attitude and then an opinion about the subject of the campaign. At this point, interpersonal communication becomes important as people influence each other;

- decision – individuals now accept or reject the innovation. Here communication needs to help people feel comfortable taking a decision;

- implementation – individuals take action by changing their behaviours or buying promoted products so knowing where to buy the product or what to do becomes really important;

- confirmation – individuals want reinforcement to show that they have made the right decision by accepting the innovation so the period after adopting the change or buying the product is important. Here PR must help to reassure adopters that they made the right decision.

This is illustrated in Table 2.2. If you think about anything you buy, for example, the Apple Watch, or if you decide to recycle plastic waste, we all go through the same process. We need to know that Apple are launching a watch or the local authority are starting a waste collection service (knowledge). Communication through what we see in the media and what we hear directly (persuasion) influences our attitudes that help us make a decision on whether or not we will buy a new watch or take up the recycling service. We then need to take action so we need information that helps us know where to go to buy the watch or how to get a recycling bin. We then need to feel good and reassured about taking these decisions.

Table 2.2 The diffusions of innovation model – a model of stages in the innovation-decision process

| Communication Channels | ||||

| Knowledge | Persuasion | Decision | Implementation | Confirmation |

| Becoming aware | Forming attitudes | Taking action | Using and applying | Reinforcing and validating |

| Use of promotion techniques | Use of appropriate messaging and importance of interpersonal communications | Use of appropriate messaging and product trials for example | Use of ‘how to’ information, demonstrations and clear instructions | Use of reassuring information so adopters know they have made right decision |

Note: This is shaped by characteristics of the Decision Making Unit

|

Note: Shaped by the perceived characteristics of the innovation

|

Either: Adoption (can lead to either continued adoption or discontinuance) Rejection (but may lead to later adoption or continued rejection) |

||

Source: Adaptation of Rogers (1983: 165), Figure 5.1

So persuasion is not something PR people need to be embarrassed about. It is one of the things we do that is important in helping our organisations communicate and survive whether it is helping to sell products and services, or changing attitudes towards healthier lifestyles or charitable concerns. The key is free will and choice to accept or reject the persuasive messaging.

So these theories help us explain some aspects of persuasion, but what about some of the detail in terms of how we persuade?

Semiotics, framing and messaging

The key to persuasion is how individuals rationalise information and arguments presented to them, make sense of things and create meaning. These arguments are underpinned by three broad concepts:

- messaging: the idea that is transmitted through the communication process. According to Windahl et al. (2009) it exists at three levels. It is a set of words or images; it has meaning attached to the words or images as intended by the individual sending it; and it has meaning attributed to it by those receiving it;

- framing: the way the message is designed to make certain elements of the argument more relevant;

- storytelling: the narrative, plot or characters that help create meaning.

According to Bateson (1972), framing is necessary to help individuals understand the communication and context helping to organise meaning and understanding. Dan and Ihlen (2011) use the metaphor of a cropping frame around a picture – the border holds together aspects of reality while marking off competing, distracting or contradictory elements. Therefore, as stated by Entman (1993: 52):

to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating context, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described.

This links to the idea of social constructivism. Here reality is created through communication rather than being expressed by it. Framing expertise then is seen as critical to successful communication (Dan and Ihlen 2011) and the key is the language used and story choice.

Language has a natural connection to the field of semiotics or the study of signs that fall out of the work of early thinkers such as the Swiss linguist Saussure (1857–1913) and the American philosopher Pierce (1839–1914). Here signs simply mean anything from which meanings may be generated and not just words; it also includes images, sounds, gestures and objects. Semiotics cannot be fully explored here as it is a vast field of study but it is useful to recognise the importance of it to PR. It focuses on what is intended (or encoded) and what is understood (decoded) and makes PR practitioners think more deeply about the basic level of communication to avoid misunderstanding.

With semiotics, meanings can be described in one of four ways: denotative (a literal or standard meaning); connotative (implied or suggested meaning); ambiguous (where the same word means different things in different contexts; for example, a coach is a form of transport or somebody who trains a team); and polysemic (whereby individuals can gain different meanings from the same set of information; for example a black cat may simply be a cat or it can mean bad luck). Also embedded within semiotics is the idea that any sign is composed of two parts. A ‘signifier’ (significant) which is the form that the sign takes and the ‘signified’ (signifié) or the concept the sign represents. Any sign is a combination of both.

So semiotics makes us think about how people use and understand information – whether it is text, sound, images, colour – to create their own meaning. It makes us think about our own assumptions and not assume everybody sees things the way we do. It puts culture and people at the heart of the communication process. Not understanding the varying reactions that people have to images, words, sounds and objects can cause misunderstanding, offence or anger. For example, for some cultures black represents death, for others it is white.

One way meaning and sensemaking is expressed is through stories and as such they can be viewed as signs. Stories help organisations create meaning and understanding as suggested by Gabriel and Connell (2010) and Cunliffe (2002). As Weick et al. (2005: 409) suggest, sensemaking is ‘an issue of language, talk, and communication. Situations, organisations, and environments are talked into existence’. The art of storytelling is fundamental to PR practice.

Cultural and Social Theories: Reality and Meaning

So we have explored the principles of basic communication, and have also looked at how people start to make sense of things and establish individual meaning. How does PR then impact on society as a whole? PR does not operate in isolation – it helps to create meaning and shape the reality of what we see all around us and what we experience, from the type of celebrity images we see on TV to how competing campaigns fight to get their voices heard. In essence, PR is shaped by culture and culture shapes it. There has been what Edwards and Hodges (2011a) and Daymon and Hodges (2009) call a sociocultural turn in PR scholarship.

A key strand of thinking running through these approaches is the modernist and postmodernist debate. Modernism is a philosophical tradition falling out of the industrialisation and transformation of Western society during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Here the idea is that there are single explanations and metanarratives that explain the social environment. From a PR point of view this links naturally to systems theory as the underlying explanation of PR practice with the idea that PR is about controlling information flows to organisational stakeholders and driving organisational effectiveness. Much of the theory so far explored perhaps falls into this category. It also places the idea of Grunig and Hunt’s (1984) four models firmly in this arena, hence it being known as the normative view of PR.

Conversely, postmodernists believe the world is far too complex to be reduced to single explanations. For PR this means there is more than one way to understand what it does and how it operates. Postmodernists often argue there is no one absolute truth but perceived truths and that PR is more complex, linked to ideas around power, elites and reality construction. One of the leading postmodernist PR scholars, Holtzhausen (2002) argues that PR is at a crossroads. It must embrace fluidity, uncertainty and diversity in a complex world both in terms of its own practice but also by exploring a variety of different theoretical ideas to understand what it does.

Sociological approaches and concepts

Over recent years, academics have started to reflect on PR, integrating ideas from social and cultural studies to bring fresh insights and interdisciplinary perspectives. This is a large area of study and this chapter can only provide a brief reflection on some of the leading developments and identify some of the key thinkers in these areas.

Put simply, sociology is the scientific study of society. In essence, it is about understanding how individuals and groups of individuals act and is interested in the creation of social structures (such as family, school, work for example) and how these impact on social activity. From a sociological perspective, there is a big debate about the influence of the micro and macro world: the micro relating to the free choice the individual has and how much power he has to take decisions about his world – this is known as agency; the macro relating to how social structures and the forces at work in the wider environment impact on the choices an individual can make. It is argued that this wider world has the biggest role to play in the choices individuals make. This is known as structure. Most sociological discussions revolve around agency and structure and the relationship between the two. Given that PR is a social activity focusing on people, it is natural that PR can connect to some of the ideas and thinkers that work in this field. Table 2.3 provides a summary of some of the ideas.

There are numerous other sociologists that are the subject of PR exploration, including Beck, Goffman, Latour and Spivak. Much work has been done in this area by Ihlen et al. (2009) and is well worth exploring by any student of PR.

A backdrop to some of this work is the concept of social constructivism developed by Berger and Luckmann (1966). The social world is created by human beings who establish social structures and create their own reality by the discourses and interactions they have together. Hence there is the idea of multiple realities depending on the type of environment in which individuals operate. Critically those who have more power have a greater chance of determining the nature of reality as they have access to greater resources. It can be argued that PR is an occupation that constructs discourses (through messaging, stories and frames) that help influence individuals’ perceptions of reality.

Often there may be competing discourses creating competing views of reality. An example of this is the debate in the 1990s about the safety of the MMR combined vaccine (measles, mumps and rubella). Although evidence showed it was safe, a paper in The Lancet in 1998 suggested that it was linked to causing bowel cancer and autism (since retracted) (Wakefield et al. 1998). For years arguments appeared for and against the combined vaccine while at the same time mothers fearing the worst sought out single vaccines or failed to get their children vaccinated at all, putting them at risk of these illnesses. Different people believed what they wanted to believe and created their own version of reality. So reality construction is a useful way to understand PR.

Table 2.3 A summary of some of the leading sociological thinkers and associated PR scholars

| Sociological thinker | Key concepts | Leading PR scholars |

| Antony Giddens | Idea of structuration linking human action to social structures; explored areas around risk and uncertainty in society PR twist: Need for sense making and shared meaning within these structures; communication can help navigate risk and build trust | Falkheimer (2007) |

| Jürgen Habermas | Suggests the idea of the public sphere – a social space that mediates between the political and private allowing discussion and negotiation; Frankfurt School argued PR and creative industries destroy the public sphere by distorting debate by only advocating views of elites His work also looks at the mechanics of communication – Theory of Communicative Action and areas around legitimacy and truthful communication PR twist: Debate about role of PR in the public sphere in generating discussion and role of advocacy; also looks to Theory of Communicative Action to understand how to build consensus and the detailed mechanics of legitimate communication |

Jensen (2001) Burkart (2007) Moloney (2006b) Ihlen (2004) |

| Pierre Bourdieu | Suggests the ideas of fields (specific areas of action such as a profession); capital (individual resources: economic, social, cultural and symbolic) and habitas (the dispositions of the field). Power is reinforced and perpetuated. Discourses help promote symbolic power PR twist: Using the lens of fields, capital and habitas to understand lack of diversity in PR practice; how does discourse as a means of maintaining power fit with PR – is PR about elites?; also looks at ideas around culture and taste and role of PR as arbiter of taste |

Edwards (2006, 2008) Ihlen (2005, 2007) |

| Michel Foucault | Focuses on discourses as production of meaning, strategies of power and the propagation of knowledge and regimes of truth; also the idea of subjectivity with individuals created by institutional discourses (and role of agency within this) PR twist: PR people develop and change discourses that impact on sociocultural practices that can normalise notions of truth; what does truth mean? | Motion and Leitch (2007) |

A cultural perspective

If one accepts the view that PR is grounded in society, then it must be entwined with the idea of culture. At the same time, the shift in focusing on the receiver of messages and the cultural influences on the audience in more traditional approaches lead us to think inevitably that PR is a cultural practice. Here the work of Curtin and Gaither (2005) and Hodges (2006) is of interest as they look at the relationship between PR and culture, suggesting PR practice is a determining force in culture and determined by it. This approach also helps us to understand how PR has evolved in different ways in different countries connecting to the work of Bentele (2010) and others who study the history of PR.

In particular, Curtin and Gaither (2005, 2007) draw on the work of Du Gay et al. (1997) and the five stages of the Circuit of Culture to show how PR is entwined in the social fabric of society. In particular, they argue PR can never be neutral because it directly or indirectly promotes a particular cultural value. PR is about meaning production through messaging, stories and framing; it shapes consumption practices through consumer PR; and is involved in regulation shaping what is culturally acceptable or not at any given moment. As such PR practitioners are ‘cultural intermediaries’, as argued by Hodges (2006).

Bringing it Together: What Does this Mean to PR?

A number of key themes emerge when exploring PR and communication theory. First, PR is interdisciplinary and draws inspiration and theoretical underpinning from a range of fields and subject areas. As L’Etang (2008) suggests, PR is a creole discipline because it intermingles different theoretical concepts and ideas. Creole is the name given to a language that results from the interrelations between two language communities and it seems fitting that the concept is being developed in a PR context.

Second, PR has traditionally been studied and explored from a normative perspective. That is, as a practice that is driven by organisational interests and explored through the ideas of systems theory, the work of Grunig and Hunt (1984) and the concept of Excellence. There is a lot for a PR practitioner and student to think about here including how to deliver effective communication campaigns and enhance organisational reputation.

Yet there are other ways to view PR from a sociological and cultural perspective. These are not necessarily in conflict and complement each other as PR matures as a practice and academic discipline. As Ihlen et al. (2009: 11) argue:

van Ruler and Vercˇ icˇ (2005) proposed viewing a sociologically orientated approach to PR not so much as an alternative but as a macroview, one that is additional to the meso (management-orientated) and micro (people-oriented) views. PR as an academic discipline needs an understanding of how the PR function works and how it is influenced by and influences social structures.

Third, as explored at the start of this chapter, PR is constantly balancing using both one-way and two-way communication in creating communication solutions, often educating organisations of the need to move to a more mutual and dialogic approach. This brings us back to power and how PR practitioners are often power brokers trying to create opportunities for more mutual and circular communication flows, while at the same time being inside an organisational structure that may not always welcome this. There is also a continued debate between using mediated and unmediated communication.

From a practical view, what does this mean to PR practice? Theory should never sit in isolation and should be used to inspire, provoke and disrupt PR thinking so that PR practitioners can do their job more effectively. Some ideas can be found in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4 How PR theories can help PR

| Knowledge source | Types of theories and concepts | Why relevant and how used |

| Organisational and economic | Systems Resource dependency |

Explains and justifies the role of PR |

| Communication | Shannon and Weaver Osgood and Schramm Westley and MacLean Maletzke Uses and gratification Hypodermic Two-step and multi-flow Grunig and Hunt (two-way symmetrical) |

Provides insight into communication complexity and a toolkit of ideas to use in devising PR solutions to problems |

| Persuasion and motivation | Public opinion Maslow hierarchy of needs Aristotle Cognitive dissonance Theory of reasoned action Theory of planned action Elaboration likelihood model Narrative and semiotics Grunig and Hunt (two-way asymmetrical) |

Puts people at the heart of the communication process. Understanding their issues and concerns. Persuasion is and can be ethical and part of what PR people do. Often persuasion linked to relationships |

| Social and cultural | Social constructivism Public sphere Cultural intermediaries Habitas, fields and social capital Power and discourses Structuration and agency Risk and uncertainty And many more too numerous to mention including feminism, post-colonial theory, presentation of self, actor–network theory … |

Helps to get PR people to think differently; understand wider societal responsibilities and impact actions have on the organisation and society; value the role of PR in society |

Conclusion

PR and communication theory is a powerful tool. It can be used for good or bad depending on the motivation of those behind it. This chapter has looked at theories of relationships, theories of cognition and behaviour and theories of mass communication. In a changing and fast-moving world PR cannot rely on one theoretical model for all the answers but by reflecting on a wide range of theories and concepts PR practitioners can be better prepared to ask the right questions and put in place communication strategies that work.

Questions for Discussion

- 1 What do you see as the differences between one-way and two-way communication approaches? Provide some examples.

- 2 Discuss the idea of noise. What impact does this have on the practice of PR?

- 3 Look at the Maletzke Model. Put yourself in the role of receiver. What type of things do you think shape the way you think and see the world?

- 4 Think about the Uses and Gratification model. How do you use media and what role does it play in your life?

- 5 Think about the idea of a network approach. How might you use this if you were devising a communication strategy? What networks do you belong to?

- 6 What are your thoughts on persuasion? Do you think it is wrong or can it be used for good?

- 7 Explain your own decision making when buying new products using the Diffusion of Innovation Model.

- 8 Choose three organisations and look at their logos and the About Us section of their website. Look at the images and words used and relate this to the idea of semiotics – meanings, signified and signifier.

- 9 Think about the last seven days, what role has media including digital media played in your life? What theories can you see at work?

- 10 How has social media affected different communication models?

Ihlen, O., van Ruler, B., and Fredriksson, M. (2009) Public Relations and Social Theory: Key figures and concepts, New York: Routledge.

L’Etang, J., (2008) Public Relations: Concepts practice and critique, London: Sage.

Tench, R. and Yeomans, L., (eds) (2013) Exploring Public Relations (3rd edn), Harlow: Pearson Education.

Windahl, S., Signitzer, B., and Olson, J. T. (2009) Using Communication Theory: An introduction to planned communication (2nd edn), London: Sage.