Chapter 8

Risk, issues and crisis management

A collaborative role for public relations

Chapter Aims

This chapter considers the role of public relations in the fields of risk, issues and crisis management, looking at both organisational and activist perspectives. It offers contemporary insight and a critique of traditional recommendations including narratives concerning corporate apologia. Practical ways to respond to an increasingly complex world are introduced and limitations of the involvement of public relations are recognised. Consideration of the self-image of public relations as a boundary-spanning function is provided with reference to global–local operations. The chapter’s overall intention is to outline a collaborative and non-prescriptive role for public relations in this evolving area.

Introduction

The modern world comprises a risk society (Beck 1992) with numerous dangers impacting on communities, organisations and individuals. From a public relations perspective, these have the potential to develop into an issue; defined as ‘a contestable point, a difference of opinion regarding fact, value, or policy, the resolution of which has consequences for the organization’s strategic plan and future success or failure’ (Heath and Palenchar 2009: 93). In a 24:7 global communications environment, the immediacy and interconnectedness of mobile, online and social media can amplify what might otherwise be issues of low or no significance. A ‘filter bubble’ (Pariser 2011) of search engine algorithms, social network endorsements and confirmation bias (tendency to attend to information that is consistent with existing views and to avoid contradictory information) may affect people’s assessment of risk. Exposure to information through the influence of trusted personalised connections in social networks, rather than traditional media channels, challenges the ability of organisations and activists to lead the narrative around risk. Indeed, the speed and potential reach of peer-to-peer networks forces professional communicators to explain risk and manage issues or crisis situations in an increasingly dynamic and complex environment where others are equipped equally to set the agenda.

Within this environment, there may be diverse opinions and varying expectations of how situations should be addressed – or even if they should be addressed. Not only are cases examined and critiqued after the event in memoires, textbooks and journal articles, but news reports and social media provide judgements and advice on what could, should and is being done in real time while an issue or crisis is occurring. Indeed such commentary needs to be anticipated and managed within planning processes as considered below.

Criticisms are often accompanied by the term ‘PR disaster’ (defined as ‘anything that could catalyse embarrassing or negative publicity for any given organization’, McCusker 2006b: 311); implying that practitioners are responsible when issues have not been addressed effectively (in the opinion of the critics). At the same time, attempts to explain an organisation’s position may be labelled as a ‘PR exercise’ (defined as ‘a situation of communication with no substance within it’, Green 2007: 215). Stauber and Rampton (1995: 16) expose the use of public relations as able to ‘only manipulate while it remains invisible’. Hence, greater discussion about public relations and the heightened profile of practitioners through the transparency of social media arguably means they can no longer be considered as ‘invisible persuaders’ (Michie 1998). Indeed, being visible means the role of public relations in managing risk, issues and crises can increasingly be recognised and critically examined.

Further, the need to gain attention in a cluttered communications environment encourages campaigns that court controversy and seek to generate public, media and other influential outrage. Those behind such initiatives commonly flout conventional expectations in their responses in order to maintain the high profile of their campaign.

Self-Image of Public Relations as a Boundary-Spanning Function

Involvement in the management of risk, issues and crisis situations positions public relations as a strategically valued function within organisations (Holtzhausen 2007), particularly when there may be significant consequences as a result of adopting a particular course of action.

Controversial Protein World Campaign, are You Beach Body Ready?

In April 2015, the Are You Beach Body Ready? poster campaign on London underground by Protein World featured a female bikini model to promote its range of weight-loss supplements. The campaign was immediately criticised as sexist, through social media, an online petition, complaints to Transport for London (TFL) and the Advertising Standards Association (ASA), plus a mass protest. The controversial campaign was mocked by members of the public, while brands such as swimsuitsforall and Dove challenged the implication that only slim bodies could be deemed #BeachBodyReady with their own creative executions of the posters. Carlsberg took a guerrilla marketing approach with its parody: Are you beer body ready? #probably.

Protein World may have anticipated the furore, particularly given the high profile of issues around body image, and concerns about ‘fat shaming’. It was certainly unapologetic in the face of criticism. The company’s Chief Executive told Channel 4 news that people who had defaced the original posters were ‘terrorists’, its Facebook page called opponents ‘irrational extremists’ and it responded to critical tweets with insults. In turn, Protein World customers, including celebrity endorsers, posted positive social media comments. The company claimed sales tripled, 5,000 new customers were attracted in four days – and the PR department was paid a bonus.

Although the ASA informed Protein World the advert should not appear again in its current form as a result of concerns about a range of health and weight loss claims, its investigation found there was no breach of rules on harm, offence or social responsibility. The advert subsequently appeared in larger format in Times Square, New York, with the company’s marketing boss, Richard Staverley quoted as saying: ‘It’s a big middle finger to everybody who bothered to sign that stupid petition in the UK. It’s a fat F-U to them all. You could say that the London protestors helped pay for the New York campaign.’

This reflects a boundary-spanning role, where public relations takes on responsibility for ‘bringing the problems of stakeholder publics into decision making’ and ‘helping organizations to adapt, or match, themselves to their environments’ (Moss et al. 2000: 283).

Gregory and Willis (2013: 35) argue public relations leaders should use their ‘ability to analyse and predict external conditions, as well as the ability to guide an organization past both visible and “hidden” dangers’, while undertaking four principal roles at four levels within the organisation as illustrated in Figure 8.1.

Each level suggests some involvement in risk, issues and crisis management. At the societal level, the strategic public relations leader acts as an orienter, the ‘protector of the organization’ (Gregory and Willis 2013: 44) implying involvement in ‘buffering, moderating or influencing the environment’ (Aldrich and Herker 1977: 218). As the navigator, the function contributes at a corporate level towards management decision making by providing bridging intelligence that ensures ‘multiple-stakeholder perspectives are taken into account’ (p. 38).

At the value-chain level, the function operates as a catalyst, in helping engage ‘close’ (p. 39) stakeholders who ‘may be regarded as troublesome’, or could play a role in decision making, ‘identify potential issues and crises’, and help ‘solve common problems’. Public relations expertise may be used in ‘coaching and mentoring those colleagues who interact with these stakeholders regularly’ (p. 39) which would be useful in identifying risk, as well as addressing issues and offering support in crisis situations. This cross-departmental role is evident at the functional level where PR offers operational support as an implementer, providing communication competence in risk, issues and crisis management.

Figure 8.1 Stakeholder levels and associated public relations leader roles

Source: based on Gregory and Willis (2013). * Value chain refers to ‘close’ (p. 39) stakeholders such as ‘customers, service users, delivery partners, suppliers, distributors, regulators, employees’ (p. 38)

Traditional risk, issues and crisis management models indicate a modernist paradigm where boundary spanning offers a rational problem-solving approach of planning, organising, leadership and control. This is notable in principles of best practice predicated on expectations of a predictable, linear development of situations, and a positivist philosophy suggesting organisational ability to control outcomes. From this perspective, boundary-spanning techniques are a means of monitoring the external and/or internal environment for potential risk, issues and crisis triggers in order to implement a set of prescriptive planned responses detailed in procedural manuals. Nystrom and Starbuck (2004:100) contend such ‘standard operating procedures’ generate inertia, complacency and prevent ‘unlearning’ that is required to ‘become receptive to new ideas’.

A more adaptive approach may utilise boundary-spanning tools to gain ongoing feedback, analysis and evaluation of problems, and support decision making by selecting from a range of possible responses.

However, in a world that has a tendency to disorder rather than order, organisations face circumstances that are irregular, irrational and uncertain in their outcomes. A more reflexive approach should seek to understand the multiplicity and diversity inherent in contemporary situations. Holtzhausen and Voto (2002) advocate this postmodern view of public relations whereby practitioners act as organisational activists, suggesting the function should operate as an internal change agent championing a transformative approach.

In enacting the boundary-spanning role, PR practitioners must be able to accommodate complexity, rather than simply to apply reductionist processes of analysis that identify straightforward solutions. Competency in looking for patterns and linkages to develop creative and collaborative solutions requires a boundary-spanning system that is more reflective, participative and capable of social learning (Wenger 2004).

This open and responsive approach enables public relations leaders to address the challenges of a global–local dimension in risk, issues and crisis management. Sriramesh (2009: 4) outlines how ‘in their boundary spanning role where they have one foot inside the organization and other in its environment, public relations professionals are in the best position to be the conduits between senior managers and external publics and stakeholders’ in enacting excellent public relations. Muzi Falconi (2014: 5) argues for a listening culture in organisations, that allows for ‘a situational (specific) approach to global stakeholder relationships governance’. This involves the public relations function enacting strategic, managerial and operational roles as illustrated in Figure 8.2.

Muzi Falconi (2014: 7) notes a process of ‘hybridization’ through integrating traditional approaches that seek to use communications to promote or protect an organisation’s reputation, with governance approaches that acknowledge key stakeholder perspectives in order to manage organisational sustainability. Local contexts are considered by gaining boundary-spanning insight into six infrastructural characteristics (Figure 8.3), developed from earlier work by Vercˇ icˇ et al. (1996).

Figure 8.2 Public relations roles based on Muzi Falconi (2014)

It is not immediately clear from these models (Figures 8.1–8.3) whether a centralised or decentralised approach to boundary spanning is most appropriate to provide coordinated and flexibly responsive insight within organisations. One option could be to adopt a Public Relations Information System Management (PRISM) approach (Figure 8.4) that would allow co-construction of knowledge ideally using an organisational intranet and/or enterprise social networking (ESN).

Figure 8.3 Specific infrastructural characteristics identified by Muzi Falconi

Figure 8.4 Public Relations Information System Management (PRISM)

The PRISM approach reflects a postmodernist perspective by encouraging reflective practice and broad participation in knowledge construction. It acknowledges that numerous narratives emerge and develop around situations and recognises a multiplicity of potential outcomes may occur locally and globally in relation to risk, issues or crisis management. A boundary-spanning approach that seeks to understand the perspectives of key individuals, and those of collectives (stakeholders and publics) supports Murphy’s (1991) mixed-motive concept whereby an organisation balances the need to pursue its own interests, with accommodating the views and needs of others. Over time, using a PRISM approach to underpin the self-image of public relations as a boundary-spanning function would build strategic value and offer an opportunity to make a more holistic, robust, and inclusive contribution to organisational decision making.

The PRISM approach involves all members of the PR function, addressing criticism (Holtzhausen 2002: 257) that traditional perspectives deny that ‘technicians often perform boundary spanning roles’. It encourages creativity and innovation, can be applied to all sizes of organisations and includes two aspects of boundary spanning identified by Aldrich and Herker (1977: 218) as ‘information processing and external representation’. Additionally, the PRISM approach supports spanning the five types of ‘mission critical’ boundaries identified by chief executives in research by Yip et al. (2009: 14):

- vertical – across levels and hierarchy;

- horizontal – across functions and expertise;

- stakeholder – external beyond the organisation;

- demographic – across diverse groups (e.g. gender, ethnicity, nationality);

- geographic – across regions and locality.

Understanding Risk

Within organisations, public relations expertise has the potential to extend beyond protecting clients or managing public interest after a situation has occurred to involve anticipating and managing understanding of risk as a precursor to issues or crisis management. Risks may emerge within the organisation or from external eventualities. The involvement of public relations may help alleviate threats (for example, to lessen or avoid risk), or to increase understanding of the necessity or context of risk. It may also, as L’Etang (2008: 80) observes, position PR practitioners as ‘apologists for inexcusable dangers or accidents’. Alternatively, public relations may help achieve activist or organisational goals by increasing recognition of hazards in order to stimulate responses from the public, government, organisations or individuals.

The concept of risk is ‘multidimensioned and nuanced’ (Haimes 2009: 1647) and hence difficult to define. McComas (2010: 462) opts for the National Research Council definition: ‘things, forces, or circumstances that pose danger to people or to what they value.’ A traditional, organisational approach to understanding risk considers three questions (Garrick and Christi 2008):

- What can go wrong?

- How likely is that to happen?

- What are the consequences if it does happen?

For most organisations, there are innumerable potential risks and the cost of addressing these may seem prohibitive. Although the classic Tylenol crisis case is held up as a best practice case study (Regester and Larkin 2008), the painkiller manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, introduced tamper-resistant bottles only after the deaths of several customers in the US in the 1980s. The risk of someone deliberately poisoning over-the-counter medicines had always existed, but until this situation actually happened its probability may have appeared so low that the costs of introducing new packaging were not justified.

However, when incidents occur, organisations may act proactively to be responsible or be forced to respond by legal, financial or reputational consequences. For example, McDonalds’ coffee cups carry a statement: contents are hot, following a legal case involving a customer who received extensive burns as a result of spilling coffee in her lap (Sommerville 2007). For McDonalds, considerable legal and financial consequences led to inclusion of the warning statement. From a PR perspective, it is debatable whether reputational risk can be eliminated entirely by warning labels.

In the UK, a Health and Safety culture has increased recognition of potential risks – and required organisations to look at ways that they, and the public, can be protected, at least legally. PR practitioners are encouraged likewise to protect the organisation’s reputation in the face of potential risks. However, Sutherland (1992) observed how even experts (such as engineers or management) frequently make decisions that fail to understand how people will react in a situation and this increases the risk of unforeseen consequences. Risk management is not an exact science, particularly when human behaviour is involved.

Risk management traditionally involves assessing likelihood (risk assessment) and possible impact (risk analysis) of foreseen consequences. Some organisations undertake causal modelling and forecasting of different outcome scenarios to anticipate unforeseen consequences. Theaker (2007) cites Answell and Wharton (1992) who view risk as unavoidable; although they claim risk assessment and analysis enable informed decisions to be made to select from possible choices of action.

Schwartz and Gibb (1999) argue this is driven by a focus on the cost of insuring against organisational liability in such circumstances. They believe organisations tend to concentrate on risks where there are predictable financial consequences, whereas reputational risks are often more difficult to evaluate.

The emergence of formal risk management processes within organisations is the result of concerns about corporate governance and other strategic matters relating to how organisations are being managed, as well as recognition of the possible costs of a crisis (financially, legally and to reputation). Data is used to evaluate hazards and ensure financial and other stakeholders understand the possible consequences of problems and how well the organisation’s management is addressing these. The scientific approach to risk assessment has seen auditors and management consultancy groups take on this analytical and reporting role. If PR is to claim equal status and enact its boundary-spanning strategic role, the function needs to take responsibility for undertaking similarly robust calculation of stakeholder relationships, emerging issues and reputational risk. Decision making would then be based on assessing hazards and outlining the benefits of different options drawing on research data and scientific analysis as discussed above.

This systems-based, management approach supports analytical decision making to assess possible outcomes. The likelihood of each outcome, along with its benefits and drawbacks can be mapped. Where possible a financial or other measure, such as impact on stakeholder relationships or reputation, can be determined to aid decision making, although it should be noted that risk assessment approaches constitute informed guesswork, even if based on research data and logical deductions. Two practical techniques that can be employed in assessing risk and responding to potential issues or crisis scenarios are:

- risk analysis matrix;

- traffic light triage system.

Risk analysis matrix

Figure 8.5 Example risk assessment matrix

This technique aims to identify and assess risk factors against existing controls. A risk rating score is assigned to enable priorities and ameliorating strategies to be determined as required (Figure 8.5). Implementing a continuous process of risk assessment helps eliminate or lessen potential consequences and enable action plans to be developed and monitored. This approach must be undertaken in conjunction with other functions that have the expertise to identify risks and may need to make operational changes. Contingency plans to communicate risk, and/or respond to potential situations should be prepared as appropriate. The potential reputational or other risk of public relations strategies or plans can be assessed using this technique, where risk of negative consequences requires corrective action unless the benefits of positive outcomes are felt to outweigh these.

Traffic light triage system

A simple triage approach indicates circumstances under which specific actions are required. As detailed in Figure 8.6, green indicates situations where routine processes and procedures could be followed. Amber signals advice or sign-off is required before proceeding. Red acts as a warning that a situation should be escalated to those with more authority to determine suitable responses. Activities falling within each band should be predetermined and reviewed regularly. The system may detail the experience and capabilities necessary to respond at a specific level and may be developed into a more sophisticated flow chart.

In undertaking risk management, PR practitioners need to take account of perceptions and acceptance of risk among stakeholders and publics. L’Etang (2008: 79) notes that risks are ‘perceptions manufactured partly through our own sense-making and judgements’. Similarly, McComas (2010: 462) observes ‘the challenge for risk management is that while some people seek zero risk in their daily lives, others are willing to accept some level of risk to obtain some type of benefit’. Indeed, risk is inherent in day-to-day life; often as a consequence of the benefits gained from modern society (Beck 1992).

Figure 8.6 Simple traffic light system

The acronym PIVOT offers a useful mnemonic as an equation to consider the likelihood of a situation, its possible impact, the organisation’s level of vulnerability and extent of anticipated public outrage in calculating a threat:

Probability × (Impact + Vulnerability) × Outrage = Threat

In public relations terms, organisations and/or issues that have a high profile may be considered to reflect high vulnerability, while outrage indicates negative public reaction. Media and other communicators act to socially amplify risk and attenuate public responses (Kasperson et al. 1988), contributing towards the level of an organisation’s vulnerability and stakeholder/public outrage.

L’Etang (2008) notes potential for panic to spiral from media coverage that Feldman and Marks (2005: xix) feel often reflects opinion (rather than fact) originating from ‘over zealous pressure groups or presentations by special-interest lobbies’. This is undoubtedly accentuated through social media online channels. A more positive role for PR in communicating risk is evident in L’Etang’s (2008: 138) statement that ‘accurate, trustworthy guidance is a public good’.

Risk Communications

McComas (2010: 462) notes that ‘effective risk management includes risk communication with affected publics’, which she defines as ‘a purposeful, iterative exchange of information among individuals, groups and institutions related to the assessment, characterization, and management of risk’.

Rucker and Petty (2006: 49) suggest risk communications can be improved by making people aware of the lack of benefits as well as risks associated with behaviours; for example, they propose cigarette packaging ‘might not only note the health dangers associated with using the product but also specifically emphasize that the product does not offer any health benefits’.

Grunig’s situational theory of publics (Grunig and Hunt 1984) proposes that publics with a greater level of interest in a situation should be the primary focus, as they will engage in proactive consideration of messages. Kim and Ni (2010) identify an activist category of publics who use their communicative action to share and forward information, which has been made easier through online communications, while Hallahan (2000) observes those with a high level of knowledge and high involvement in an issue are predisposed to monitor situations and organise if required, being frequently involved in issue advocacy.

McComas (2010) notes, however, that risk communications have traditionally been one-sided, becoming persuasive if publics do not respond to information presented. She claims the emphasis of risk communications is shifting to involve publics on the basis of understanding psychological and social factors affecting their decision making.

Palenchar (2010: 451) supports ‘shared dialogue’ over ‘information push’ in encouraging ‘vigilant community stakeholders’ and says risk communications can help influence choices and reduce uncertainty felt when people are faced with risk. As such, communications help minimise or eliminate cognitive dissonance (mental discomfort) from conflicting information or inconsistent feelings. However, risk communications can be used to reduce or to increase public perceptions of the need to take action, raising questions of ethics. Even if not deliberately lying, communicating risk means information could be selected to obfuscate or at least to downplay or overplay the situation depending on the aims of the client organisation.

In particular, care is required in communicating scientific facts and statistics that emerge from risk analysis. Technical information may be difficult for non-experts to understand, and those affected by an issue may react instinctively or engage in peripheral processing (when little thought is given to issues, particularly by those with little motivation or who are unable to consider messages in any depth; Petty and Cacioppo 1986). This presents a danger that rational and informed debate is replaced by simplistic communications leading to public over-reaction, risk aversion and ignoring valid warnings (cry wolf phenomenon, Kam 2004) or a lack of motivation to respond (learned helplessness phenomenon, Badhwar 2009). People could feel disempowered by communications involving ‘risk experts’ (L’Etang 2008: 80) who present contradictory evidence or disagree over its interpretation.

Palenchar (2010) argues a need to work in partnership with publics to manage risk. However, he does not acknowledge power differentials whereby it is normally others who face risk as a result of organisational decisions or action. The extent to which risk communications are executed in order to achieve organisational goals, improve public understanding and engagement in developing outcomes, or reflect corporate responsibility in doing the right thing are matters for debate according to Palenchar (2010). He claims such concerns are reflected in contemporary best practice approaches that emphasise building trust, transparency, respect for others and ongoing communications that acknowledge the uncertainty of risk situations.

Issues Management

L’Etang (2004) notes the antecedents of issues management in the intelligence service enacted by British public relations practitioners in the 1930s, although the term issues management is credited to Howard Chase in 1976, who had concerns about the influence of activists and non-governmental organisations on public policy, at the expense of corporations (Jaques 2010). During the 1980s, issues management became viewed as an important preventative step in proactive crisis avoidance.

Jaques (2010) notes a lack of agreement in defining issues management, although Tucker and Broom (1993, cited by Regester and Larkin 2008: 44) believe it enables organisations to ‘reduce risk, create opportunities and manage image (corporate reputation) as an organizational asset’. Cutlip et al. (2000) define the essence of issues management as early identification and designing strategic responses to mitigate or capitalise on possible consequences. Grunig and Hunt (1984: 296) quote Buchholz (1982) as saying ‘The interactive corporation tries to get a reasonably accurate agenda of public issues that it should be concerned with … and develops constructive approaches to these issues’.

These statements do not explicitly recognise the opportunity for public relations to engage others and L’Etang (2008: 86) expresses concern that issues monitoring implies a ‘surveillance’ approach, whereby organisations seek to exert power over those being investigated.

Research may reveal several, possibly opposing points of view surrounding an issue, although it may be possible to identify common themes or groups of people who hold similar views. This enables responses to be developed to meet particular needs or to engage with the most frequently raised aspect of the issue. It should be remembered, however, that the organisation should be consistent in its response to avoid communicating potentially conflicting messages. Responses should be clear about the organisation’s position and not include statements merely to gain favour that are at odds with its actions.

Identification of issues should acknowledge that an operational response, rather than a persuasive communications one, may be required and that an issue may be a matter of legitimate concern where public relations practitioners need to act as activists within organisations (Holtzhausen 2000) and insist on internal change.

It is important to understand that issues do not exist in isolation and may be linked to other issues. For example, the issue of genetically modified food relates to the wider debate on food poverty, which depends on factors such as population numbers, food technology, transportation, political structure, cultural traditions, and so forth. An organisation’s response may need to be placed in the wider framework of debate, or consider the impact of related issues on stakeholders and publics.

Similarly, any response to a situation can cause different issues to arise. For example, in the UK since 2001 road tax (vehicle excise duty) has been used to encourage motorists to switch to low carbon cars, supported by the development and promotion of more environmentally responsible vehicles. The concomitant fall in taxation revenues resulted in a government policy change in July 2015, which the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders said threatened the ability of the automotive sector to meet stricter emissions targets. The RAC motoring organisation and the Civil Engineering Contractors Association (CECA) were among those welcoming the shift in political narrative to using road tax to generate income to invest in road building, although this has been criticised by campaigning body, Friends of the Earth.

This example illustrates the observation by Jaques (2010: 436) that issues management is ‘used by government agencies themselves to promote and implement new policy, and by NGOs [non-governmental organisations], activists, and community groups to facilitate public participation in the process’. However, issues management has predominantly been considered from the organisational perspective, and primarily as a defence mechanism against activist opposition (L’Etang 2008). Those who are most critical of public relations, such as Stauber and Rampton (1995), focus on this dominant paradigm to highlight the actions of organisations, while ignoring the use of PR tactics when employed by activists. The similarity in approach across various types of organisations is evident both in public expressions around an issue, and the use of public affairs or political lobbying activities to seek to influence decisions.

Smith and Ferguson (2010: 405) note that activism has not been embraced as a ‘legitimate public relations practice’ despite its close linkage to issues management. However, a sociocultural ‘turn’ (Edwards and Hodges 2011b: 1) in scholarship examines the broader role of public relations in society. For example, Demetrious (2013) considers public relations, activism and social change in relation to ‘communicative activities’ (p. 6) around ‘contested issues’ (p. 33).

Jaques (2010: 437) feels the idea of disputation is useful in emphasising that to be considered as an issue a matter must involve ‘contending opinions’ between two or more parties. He states the potential impact of issues should be an important consideration, particularly in focusing attention on matters that are most significant; listing six factors that justify formal issues management:

- involvement of external parties;

- no black-and-white answer;

- likely involvement of public policy or regulation;

- emotion rather than data likely to prevail;

- occurring in public, or via news media;

- with greatest risk of failure or becoming a crisis that threatens the entire organisation.

As already considered, issues management literature has tended to propose simple linear models:

- Temporal models illustrate how issues develop through sequential stages showing escalation of interest and debate before the issue peaks, is resolved (possibly by legislation) or declines in relevance.

- Process planning models can be broadly summarised as: defining the issue, analysis, considering potential solutions, implementation and evaluation.

Jaques (2010) observes such models argue that if an organisation does not act promptly, it will face fewer choices, greater costs and less chance of achieving a positive outcome. The suggestion is that organisations, and specifically their public relations advisors, can control the development of issues and prevent crises arising. However, limits of communications in issues management need to be recognised. For example, although Nike initially used media relations to defend its position in response to criticisms of labour practices in its global supply chain (Neef 2004), it subsequently adopted a leadership position based on monitoring, industry codes, transparency in its operations and social responsibility (Ferrell et al. 2009).

This highlights Jaques’ (2010) call for organisations to take issues management seriously and ensure intelligence gathering translates into action. As with earlier examples of McDonalds and Tylenol, the potential for a crisis situation is often known – but for various reasons, no action is taken to avoid a potential risk from becoming a real crisis. Jaques (2010) emphasises the need for post-crisis management (as in the Nike example) to avoid recurrence and development of the initial issue into other areas.

Many crises can have long-term legacies particularly when litigation or political inquiries keep an issue alive potentially for many years. This is clear in the case of the travel firm, Thomas Cook, following the deaths of two children by carbon monoxide poisoning in 2006. Although legally found to be not responsible, the refusal of the company’s CEO to offer the parents an apology at the formal inquest in 2015 resulted in ongoing public, media and political criticism of the organisation.

Situations that initially reveal operational or management problems can become significant reputational issues and result in a lasting decline in trust. Jaques (2010) recommends issues management needs to continue after an immediate crisis is resolved and become embedded into ongoing strategic management.

A holistic view of issues management is presented in Jaques’ (2010) relational model that includes issues and risk management within crisis prevention, which is distinct from crisis preparedness, crisis event management and post-crisis management. Crisis preparedness involves formal systems necessary in case a crisis occurs (such as producing manuals, policies, training and resource allocation). In contrast, issues management seeks to avoid a crisis from occurring alongside actions such as audits, risk assessment and environmental scanning.

Active Approaches to Issues

An alternative view of issues management is its use by organisations as ‘opportunity management’ (Jaques 2002:142) or voluntarily to raise issues of concern and develop mutually acceptable solutions with active publics and authorities.

The Chase-Jones model (1979 cited by Gaunt and Ollenburger 1995) includes two proactive strategies reflecting this perspective: adaptive (being open to change) and dynamic (being an advocate of change). These approaches are echoed in social responsibility models proposing responsiveness in seeking to contribute – and gain a reputation – as a leader in ethical or philanthropic matters. In addressing society’s needs, issues management enables an organisation to seek out opportunities to advance its strategic position – and demonstrate social responsibility.

Smuddle and Courtright (2010: 184) call for responsible public relations practitioners as members of professional bodies to advocate ethical responsiveness to ‘serve the public interest’ and ‘aid informed public debate’. As such, practitioners may reflect a postmodernist perspective by challenging organisational behaviour from within as internal activists (Holtzhausen 2002) or as the organisation’s conscience or ethical guardian (although this is seen as problematic in reality; L’Etang 2003).

Citing L. A. Grunig, Holtzhausen (2000) notes PR practitioners routinely deal with external activists, necessitating skills in building relationships and accepting others may have superior power (for example through media relations). As noted earlier, the 24:7 global communications environment enables mobile, online and social media to be used to amplify issues, increasing the power of individuals and activist groups. It is therefore, increasingly necessary for practitioners to identify, and engage with, those who have power in influencing the development of an issue, although this may be difficult to achieve.

An active approach to issues management is evident in the work of organisations seeking to ‘elevate a society’s value standards’ (Smith and Ferguson 2010: 396). Examining the role of public relations within community, NGO or activist groups, enables their work to be considered as part of the field (not opposed to it) and encourages a less traditional organisational-centric or defensive approach to issues management.

There is a long history of charities, NGOs and independent groups of highly active publics using public relations to raise the profile of issues or stimulate crisis situations, in order to get their voice heard and change public opinion (Bourland-Davis et al. 2010). The 1960s and 1970s witnessed the formation of global activist movements (e.g. Amnesty International, Greenpeace, Worldwide Fund for Nature) that have become expert at engaging and motivating stakeholders through high-profile public relations campaigns. Bourland-Davis et al. (2010) believe the success of activist organisations highlights weaknesses in the ‘default position of excellent public relations’ (p. 419), notably through the way in which such bodies use one-way communication techniques and heighten perceptions of conflict rather than seek collaboration.

Smith and Ferguson (2001) cite Heath’s (1997) cyclical model of activism comprising five stages:

- strain – recognise, define and seek legitimacy for issues;

- mobilisation – form groups, establish communication systems, mobilise resources;

- confrontation – push government or organisations to resolve problems;

- negotiation – exchange of messages;

- resolution – temporary/permanent solutions.

Collaboration may be evident in the need for activist groups to work together (or even merge) to better fight a particular issue. At other times, groups splinter as different elements refine their objectives. In this way, there are often moderate and more extreme groups working around any particular issue. For example, in the animal rights movement, groups may be divided into reformists or abolitionists (Guither 1998); the former being more willing to work within the existing social system to address issues of concern.

Arguments already considered for building relationships and achieving mutually acceptable solutions apply to organisations and activists, although both may be suspicious of the other and question their motives for seeking a dialogue.

Crisis Management

Coombs (2014: 1) argues ‘no organization is immune to crises’, which he defines (p. 3) as: ‘the perception of an unpredictable event that threatens the important expectations of stakeholders related to health, safety, environmental and economic issues, and can seriously impact an organization’s performance and generate negative outcomes.’

At the international level, major disasters include terrorist attacks, product recalls and environmental emergencies. Organisations hit the headlines and online grapevine for customer relations issues and ill-judged public statements – for example, former BP CEO Tony Hayward’s infamous remark: ‘I’d like my life back’ at the height of the Gulf of Mexico oil crisis. Crisis situations also affect public sector bodies, charities, small local businesses and individuals.

Personal Impact of Crisis Management

Although the term ‘crisis worker’ is most commonly applied to professionals involved in caring for others who have experienced a trauma, arguably it relates to the role of PR practitioners in crisis management. Indeed, Bridgen (2014) has considered public relations as ‘dirty work’, a term applied by Hughes (1951) to jobs that carry a physical, social or moral taint. PR practitioners may be involved in crisis situations involving deaths, serious injury or other traumatic circumstances. They may be faced with presenting a position they find problematic, or forced to exert emotional control in extreme situations. They may be held personally, and thanks to social media, publicly, accountable for an organisation’s crisis response. Indeed, through their social media activities, some PR practitioners have become the centre of a crisis that has threatened their careers and even their safety. At the least, working in public relations creates tension between empathy for the position of others and seeking to protect an organisation’s reputation.

Crisis management is commonly seen as the pinnacle of professional competence, positioned as a strategic role, carrying heroic connotations not often associated with the occupation. Handling the stress of a crisis situation may be regarded as a development opportunity within a public relations career, reflecting professional resilience. For those unable to cope with the pressure, there may be a sense of failure. However, there is little focus on these personal aspects of crisis management in public relations literature or practice.

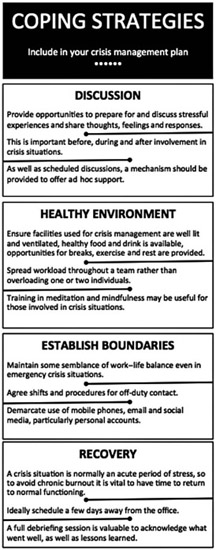

Within crisis preparedness organisations should acknowledge the potential for stress, monitor the pressure experienced by individuals, and make coping resources available for those both who routinely face crisis situations and for whom a major incident is a rare occurrence. It is essential to normalise rather than stigmatise practitioners who feel the strain of a crisis situation or experience mental health conditions. Research into the lived experiences of PR practitioners involved in crisis management, and establishment of a community of practice to identify specific stressors, consider any challenges faced in developing resilience and identify how to sustain mental well-being would be helpful. Coping strategies that could be adopted within a crisis management plan include:

- Discussion. Providing opportunities to prepare for and discuss stressful experiences, and share thoughts, feelings and responses. This is important before, during and after involvement in crisis situations. As well as scheduled discussions, a mechanism should be provided to offer ad hoc support.

- Healthy environment. Ensuring that facilities used for crisis management are well lit and ventilated, healthy food and drink is available, opportunities for breaks, exercise and rest are provided and workload is spread throughout a team rather than overloading one or two individuals. Training in meditation and mindfulness may be useful for those involved in crisis situations.

- Established boundaries. Maintaining some semblance of work–life balance even in emergency crisis situations. Agreeing shifts and procedures for off-duty contact are important, along with demarcation for use of mobile phones, email and social media, particularly personal accounts.

- Recovery. A crisis situation is normally an acute period of stress, so to avoid chronic burnout it is vital to have time to return to normal functioning. Ideally an opportunity to take a few days away should be taken. A full debriefing session is valuable to acknowledge what went well, as well as lessons learned.

Figure 8.7 Crisis management coping strategies

The way in which an organisation responds to a crisis and ensures that it is effectively resolved – in the long term – may affect its reputation for many years. Indeed, in a digital age, any crisis remains visible through archived media coverage, activist sites, blogs and social media postings.

Crisis communications is one area where the value of public relations should be indisputable. Organisations facing crises (driven by external or internal forces) rely on public relations demonstrating its strategic significance, and engaging the attention of senior management. However, the involvement of public relations is increasingly challenged by legal firms, and criticised by those opposed to conventional crisis communication approaches (Dezenhall and Weber 2007).

Gilpin and Murphy (2008: 4) state that ‘a dominant paradigm has emerged’ in crisis management based on a process of intelligence gathering through environmental scanning as a defence against potential crisis situations. This approach can be seen in examples used to validate a mantra of ‘golden rules’ (Regester and Larkin 2008) or commandments (Seitel 1998). Indeed, adherence to prescribed practices means an organisation (such as Johnson & Johnson over Tylenol) is held up as an exemplar (winning industry awards), while those who do not conform (such as Exxon with the Valdez crisis) are slated as the worst (Pauly and Hutchison 2005). In this way, public relations practitioners are encouraged to follow a ‘right way’ regardless of the actual crisis situation they may face.

Gilpin and Murphy (2008: 5) argue against ‘overly rigid crisis planning procedures’ as these position PR as capable of delivering more than may be possible and risk practitioners appearing to fail as a result of misplaced expectations. A more flexible approach is evident in the British Standard for Crisis Management (BS 11200) published in 2014, which promotes consideration of the actual situation being faced by the particular organisation at a specific time and identifies the scope of required capabilities, including crisis leadership and communication.

BS 11200 contrasts with traditional systems approaches that advocate developing plans for specific situations (Fearn-Banks 2007) based on action lists necessary to prepare and manage a particular eventuality. Coombs (2014) draws on attribution theory (how people attribute responsibility and react towards organisations) in presenting a Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) that presents four ‘postures’ organised from the ten most common crisis responses (Figure 8.8). SCCT reflects a receiver-oriented approach predicated on how stakeholders perceive a crisis and respond to crisis response strategies.

Figure 8.8 Crisis response strategies proposed by Coombs (2014)

Coombs’ work takes a social science approach to obtain evidence to substantiate recommended strategies. However, it reflects a reductionist approach in seeking to identify typologies of crises, stakeholder perceptions and organisational responses.

This may suffice for some crises, but does not address complex and changing situations, involving multiple stakeholders and interests (inside and outside the organisation), changing scenarios and dynamic communications networks.

Rather than expecting a crisis to behave in a particular way, and respond with particular solutions, PR practitioners ought to be equipped to assess shifting events and respond with an appropriate range of tools. Gilpin and Murphy (2008: 7) suggest learning from complexity theory by recognising ‘uncertainty and unpredictability’ in crisis situations with a focus on ‘flexibility and alertness’.

Unpredictability is often apparent in the first indication of a crisis (Seitel 1998), such as an online comment or photograph published through social media. Initial reports may lead to ongoing discussion, speculation (ill-founded or justified) and both escalation and spread of awareness. The PR function will be expected to respond – even if verifiable information is not yet available. Linear crisis management models and traditional advice propose that unless prompt, honest, full disclosure is made immediately, organisations will lose control of the situation, as others present information and views on the situation – often critical. While this may be appropriate in many circumstances, decisions should be made in light of the particular situation, rather than relying on the rule of thumb to tell it all and tell it fast.

Coombs (2014) asserts that crises are perceptual and consequently public relations practitioners need to manage not only information, but how situations are understood and interpreted by others. This implies crisis management is a narrative process requiring rhetorical approaches. It is natural for public relations practitioners, as communicators, to focus on this aspect of a crisis.

However, it must be remembered that crises generally occur for a reason – and operational or managerial causes and consequences need to be addressed, not simply replaced by immediate responses, corporate apologia or image management techniques. In such cases, any underlying issue is likely to reoccur and when it does, any goodwill that may have supported communications initially is likely to have dissipated, resulting in a more serious situation second time around.

The focus on managing perceptions rather than solving underlying causes reinforces the idea that public relations alone can control a crisis. Indeed, it relates to tactics employed by publicists and lawyers where connections, manipulation, threats or legal restraints are employed. Online communications have shown it is not so easy to control bad news, and seeking to prevent disclosure or frame the narrative can exacerbate a resulting crisis and put the organisation in a much worse light.

The changing nature of crisis management necessitates continuous learning ‘to equip key managers with the capabilities, flexibility and confidence to deal with sudden and unexpected problems/events – or shifts in public perception of any such problems/events’ (Robert and Lajtha 2002: 181). Likewise, Gilpin and Murphy (2008) advocate a type of expertise based on establishing strong relationships and robust knowledge of the organisation; as well as developing competencies in intuition, active sense-making, sensitivity to change, and rapid decision making. They call for maintaining dialogue within networks of relationships within and outside the organisation (including communities of practice to facilitate problem-resolution). These ideas require a shift towards improvisation and away from rational planning; although Gilpin and Murphy (2008) see this as evolution rather than revolution and extend its use to issues and reputation management.

Apologia

Aristotle initially conceived the term apologia, which Campbell et al. (2015: 332) label as ‘the rhetoric of self-defense, image-repair or crisis management’. Today, there are ‘well-defined rhetorical expectations’ of crisis responses (p. 325) and violating these is likely to generate additional negative attention. Despite advocating honesty and openness, the primary focus of ‘best practice’ rules seems to be on making an apology – which from the organisational perspective may be viewed as a discourse of defence (Hearit 1994) or one of rebuilding reputation (Coombs 2014).

In the case of activist groups, alternative discourse or ‘rhetoric of subversion’ (Campbell et al. 2015: 332) can be a successful approach with the use of confrontation, mass rallies, shock tactics and other techniques that would be unacceptable if used by public relations practitioners working on behalf of organizations (as in the Protein World example at the start of this chapter).

Using apologia, PR practitioners seek to influence judgements by presenting facts about the organisation’s actions (from its point of view), to control the nature of debate (and influence any outcomes that may be sought by those affected by a crisis) and engage in image repair by altering perceptions. Apologia may be used to reinforce the good character of the organisation, deny wrongdoing, differentiate problematic actions, transcend the current situation, shift blame or attack the accuser, present corrective action or make a confession (Campbell et al. 2015).

Carefully crafted apologies constitute a one-way method of persuasive communications, and Lazare (2005: 7) observes an ‘apology phenomenon’ reflecting what he asserts are pseudo-apologies, where sorrow is expressed conditionally rather than acknowledging responsibility (Hearit 2001). Interestingly, Campbell et al. (2015) conclude that well-publicised speeches of self-defence tend to fail, despite modern society’s demands that they be made.

Corbett (1988: xi) states:

What perversity is there in the human psyche that makes us enjoy the spectacle of human beings desperately trying to answer the charges leveled against them? Maybe secretly, as we read or listen, we say to ourselves, ‘Ah, there but for the grace of God go I’.

However, such apologies may be a form of power-rebalance when the media, and public, are able to exert some form of contrition from organisations or celebrities. Indeed, such apologies may not be taken seriously; being seen as a form of entertainment where powerful figures are required to embarrass themselves. Their continuing dominance as a ‘best practice’ crisis response strategy highlights the need for traditional approaches to be reconsidered.

Conclusion

Risk, issues and crisis management are important to the self-image of public relations in positioning the function in a reflexive, strategic boundary-spanning role. A collaborative, research-based approach is recommended to identify risks, assess probability of their occurrence and potential consequences (financial, legal or reputational), as well as to understand emerging issues from the perspective of others inside and outside the organisation who may be involved or affected. This approach goes beyond the organisational-centric focus that dominates public relations literature, and outlines a different perspective to issues management to accommodate a modern, complex world.

Emerging theories propose a role for public relations based on relationship building and co-orientation in managing risk, addressing issues and resolving crisis situations. PR practitioners are advised to accept uncertainty and complexity to develop responses that are contingent on the particular organisation, specific situation and other varying factors rather than be driven by generic rules.

A shift in focus questions corporate apologia as a defensive or subversive tactic that, although largely unsuccessful, may have entertainment or power-rebalancing value to the media and public.

The contemporary risk society exists in a 24:7 dynamic global communications environment, which presents challenges to rational management of issues and crisis, and places pressures on public relations practitioners as crisis workers. By recognising risk as unavoidable, public relations can be used to increase understanding rather than excuse organisational behaviour. At the same time, greater realism about what public relations can, and cannot achieve is required. This could affect the status public relations has sought as a controller of crisis situations, but avoid the function being seen to fail when its ‘best practice’ approaches do not deliver miraculous results.

The role for public relations practitioners may increasingly be as internal activists, raising and addressing issues within an organisation on the basis of a toolkit of appropriate techniques, rather than a limited ‘best practice’ approach.

- 1 How is risk identified and managed in your organisation – and what role does public relations play in this?

- 2 Why do some brands deliberately court controversy?

- 3 Are there any differences in how activists and other organisations respond to situations involving risk, issues or crises?

- 4 Do your own experiences reflect a collaborative boundary-spanning role for public relations?

- 5 What are the benefits and drawbacks of establishing ‘best practice’ rules for risk, issues and crisis management?

- 6 How could you use social media to identify warning signs of potential issues or crisis situations?

- 7 What challenges does an increasingly complex world present for the involvement of public relations in this area?

- 8 Are you influenced by public apologies made by organisations, politicians or celebrities?

- 9 Do you feel that involvement in crisis management would be an asset to your career development?

- 10 What coping strategies would you employ if faced with managing a crisis situation?

Further Reading

BS 11200 (2014) Crisis Management. Guidance and good practice, London: BSI.

Dezenhall, E. and Weber, J. (2007) Damage Control: Why everything you know about crisis management is wrong, New York: Portfolio.

Challenges conventional PR responses with a focus on defensive strategies.

Fearn-Banks, K. (2007) Crisis Communications: A casebook approach, London: Routledge.

A solid case study reflection of practical crisis approaches.

Gilpin, D. R. and Murphy, P. J. (2008) Crisis Management in a Complex World, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Presents an alternative perspective for a world of uncertainty.