6 Why?

Why Why?

Why? is the most powerful question you can ask during the critical thinking process. Asking why results in answers that provide us with knowledge, thereby giving us choices, and as Sir Francis Bacon said, “Knowledge is power.” Knowledge lets us be more creative, solve problems, and make better decisions.

For example, let's say that someone asks you to move all the furniture in one room to another. You might ask, “Why?” and discover the carpets are getting cleaned tomorrow. Once you know this, you would make sure to move the furniture to a room without a carpet.

For a more complex example of why, imagine you're in a meeting to discuss making a particular process faster. You might typically create a process flow diagram and then discuss how you could eliminate or streamline some of the steps. This would certainly lead to a faster process, but imagine if you asked, “Why do we want to speed up this process?” That conversation might lead you to discover that the real objective is to ensure timely delivery of products to your customers. This knowledge might prompt you to suggest—in addition to speeding up delivery with this faster process—you can make a huge difference by looking at how you forecast product demand so that you know what to make in advance.

In this chapter, we'll cover four reasons why we ask why. But before we get into that, we need to look at what happens when you ask why. Let's say your manager asks you for a report or information on a project and you respond by asking, “Why?” He'd likely interpret your response negatively—as though you're questioning the request, being insubordinate, implying that you think it's a bad idea, or simply not caring. But that's not what this why is.

Your why really means, “To do the best job I can, to accomplish what you need, and to make sure I provide you with the information, product, or deliverable to address what issue you have, I need to understand more about what you are asking. So, why do you want that report?”

You ask why:

- to distinguish this from that;

- to find a root cause;

- to get to “I don't know”; and

- to get to the double because (Because!!).

Let's look at each of these list items in more detail.

Ask Why to Distinguish This from That

Have you ever been asked for something or to perform a task, and got a response similar to the following when you delivered it: “Oh, that's not what I needed,” or “That's not what I asked for”? Perhaps you delivered what was requested, but the requestor asked for something else later on because he or she realized what was asked for initially wasn't what was needed in the first place. Not only is this a waste of time, but it's also frustrating.

Consider the following simple example: A man asks you for a roll of tape. You give him a roll of tape. He comes back and asks for more tape. You give him more tape. He comes back and asks you for some string. You give him string. Then you see him carry out a package that has all kinds of tape and string on it. Your reaction might be, “Oh, if I had known you needed to ship a box, I would have just given you the premade shipping boxes with the packing tape stored over here.”

Here is a slightly more complex example: A manager asks, “Can you please run a report showing the sales of each product for the past four months?” You run the report. The manager subsequently asks, “Now can you show the sales of each product by salesperson?” You run that report. “Now, can you do one for the marketing programs that have been approved for the next six months?” You run that report, and as you deliver the report, you notice that your manager is creating a PowerPoint presentation titled Sales Forecast.

You say, “Excuse me, but are you requesting this data so that you can create a sales forecast?” Your manager confirms. You reply, “Oh, if that's what you want to create, you might want the product release schedule over the next six months, because we are updating many of our products and expect a significant increase in revenue.”

Interactions such as these happen all the time. We often ask others to do something without bothering to give them the reason why we want those actions performed. Although it's not practical to explain yourself every time you ask for something, it is prudent to do so when it's for a substantial issue or problem. If you ask someone to make a copy of an invoice, you need not explain why—as long as it doesn't matter to you that it might end up being a black-and-white copy on regular paper. However, if you asked someone to make a copy of a presentation for you, explaining you want the copy for an executive leadership presentation might ensure your copies are in color, on bond paper, and bound.

As you can see from both of these examples, knowing the why at the beginning would have made a big difference in how a person approached these tasks—and likely would have made the overall process much more efficient for everyone involved.

When someone asks you to do something—run an errand, create a report, call a customer, start a new initiative, revise a product, check a reference, create a schedule, or just about anything else—our company calls the request asking for this. In other words, “Please do this,” “This needs to happen,” or “Can you do this?” You might be given a list of this's. All of these are instances in which you should ask why? Specifically, “Why do you want this?” or “Why are you asking for this?” or “Why do this?”

Again, you're not questioning the person's reason for asking; you're just trying to get a better understanding of the issue. You're looking for the person to say, “I need you to do this because I need this in order to accomplish that,” or “We need this so we can figure out that.” In the previous example, when the manager asks for a report, that's the this. “I need this (report).” If asked why, the response may have been, “Because I'm creating a sales forecast.” The sales forecast is the that. It's the real headscratcher. Running a report is just a to-do item. That is what you want to learn about—because that is most likely the real headscratcher this person is looking to solve. This is usually just a to-do, a task required to accomplish that.

Once you understand what that is, your response might be, “Oh, if that is your issue or problem, then not only do you need this, but you also need this other report,” or “Oh, if you want to solve that, then this isn't what you need; you need this other thing over there.” Last, you might respond, “This is exactly what you need to solve that.”

Figure 6.1 is the image we use to describe the relationship between this and that. It illustrates multiple this's (to-dos) that might be requested. You then ask why to discover that, the real headscratcher to be solved.

The Takeaway

Asking why helps distinguish this from that—and although this may be an important step, that is the headscratcher. Why allows you to uncover other issues and helps determine whether the problem for which you are seeking answers (this) is the real headscratcher to be solved (that).

Ask Why to Get to a Root Cause

We also ask why when we want to understand an event that has occurred: something breaks; a customer cancels his or her account; a vendor is late on a deliverable; or we miss a schedule, lose a sale, or exceed our budget. The event could be a positive, too: we beat the forecast, completed the project ahead of schedule, or increased our customer count. We group these events together as “This result happened.”

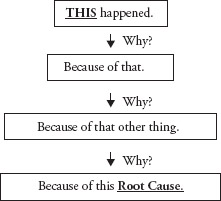

We use why to drill down until we reach a root cause. You ask, “Why did this happen?” The response you are looking for is “Because of that.” Then you ask, “Why did that happen?” You anticipate the response “Because of that other event.” Additional probing with why will get you to a root cause—the initial decision, failure, or event that eventually led to the result. It could be a successful result you want to duplicate or a result you want to prevent in the future.

Here's an example: You print a document from your computer, but when you go to the printer, there's nothing there. You go back to your machine and try it again, making sure you're sending to the right printer. You go to the printer, and the document is not there. You ask why and discover the printer is out of paper. You put paper in. Lots of other things are printing, and you figure these are other people's jobs that have been stacking up—so you wait. The printer stops, and your document still isn't there. You ask why, because the printer seems to work, just not for you. You try printing to another printer, but nothing comes out. Again, you question why. You notice you have three documents waiting to print: the two you tried to print to the original printer and the one you tried to print to the other printer. Why? Finally you discover the problem: your computer isn't connected to the network. Asking why again helps you learn the network cable is not connected. You then remember that you took your laptop home last night to do some work and forgot to plug in the network cable when you returned this morning. You plug the cable in, and the printer starts printing your stuff. The failure to connect the network cable was the root cause of your printing difficulties.

Figure 6.2 illustrates how you drill down using why to find a root cause.

Something happens: “This happened.”

You ask, “Why?”

The response: “Because of that.”

You ask, “Why?”

The response: “Because of that other thing.”

You ask, “Why?”

The response: “Because of this.”

You keep diving deeper until you find the root cause.

The Takeaway

Asking why—sometimes more than once—helps you discover a root cause. Knowing a root cause helps prevent undesirable results from occurring again or allows you to repeat a desirable result.

Ask Why to Get to “I Don't Know”

When you ask why, you may get the response “I don't know”—perhaps while asking questions as you look for the root cause:

“Why did that customer cancel?”

“I don't know.”

“Why did that component break?”

“Why don't we have enough candidates to interview?”

“I don't know.”

Perhaps when distinguishing this from that, you ask, “Why are we doing this?” You might receive the response “I don't know.”

Although it might seem like a lack of response, “I don't know” is actually a very important discovery. You want to continue to ask why to get to “I don't know,” because you most likely need this unknown knowledge to achieve clarity on the issue. “I don't know” also clarifies the boundaries of knowledge you and others have about a situation. Get to “I don't know,” but then find out those answers—because you have to know when it comes to critical thinking! A response of “I don't know” is a signal to ask other questions, such as:

“Who might know that you can ask to find out?”

“How can we find out?”

“Can we make any assumptions that will allow us to know and then validate or invalidate those assumptions later?”

You can't move forward when the situation is I don't know.

The Takeaway

Ask why to get to “I don't know,” and then go learn what you don't know.

Ask Why to Get to Because!!

We call this the double because—a because with two exclamation points. It's a because you can't reasonably do anything about. For example, let's say you want to solve the following: “How can I make it easier to pay all my bills?” There are rent or a mortgage, taxes, and utility bills to pay; food, clothes, and gas to buy; and maybe even college or other school expenses. You surmise you could accomplish this if you didn't have to pay taxes. Well, having to pay taxes is a because!! You can march on Washington and try to get taxes eliminated, or you can break the law and not pay taxes. But assuming you don't do either of those, you have to pay taxes. You still have to solve your headscratcher. There's always a way; it's just not that way. Go bang your head against a different wall, because that taxes wall isn't moving. Because!! is a constraint to your solution.

If you work in a regulated industry, such as pharmaceuticals, financial, food, or communications, you have to abide by certain laws enforced by the Food and Drug Administration, the Federal Communications Commission, or the Securities and Exchange Commission, and numerous other local, state, and federal agencies. You might regularly hear (and ask), “Why do we have to do all this paperwork? Why do we have to fill in these forms, report all this data, or run all these trials?” It's okay to ask and even to push to discern whether these requirements are truly immovable. However, if the effort or timeline to alter these regulations is significant—or until the law gets changed—these are all examples of because!! You still have to get your project done, on budget, on time, and with the available people you have. There is a way, but it won't be by getting the because!! to go away.

The Takeaway

Asking why helps you get to because!!—which is a constraint to your eventual solution.

Getting Started with Why

You can use why in many circumstances to dive deeper into what the problem, issue, or goal is and get a clearer understanding of your headscratcher. Here are just a few examples of when you can use why:

- When setting goals: Ask, “Why is that the goal?”

- When setting and evaluating priorities: You want to consider why something is a top priority. Ask, “Why is that so crucial? Why is that more important than these other initiatives?”

- When someone raises an issue as a problem: Ask, “Why is that a problem?” This will allow you to discern whether it's really a problem that needs to be solved—or solved in the timeframe you've determined.

- When something unexpected or unplanned occurs: In this situation you might want to look for the root cause by asking, “Why did that occur?” or “Why did we miss that?”

- When receiving or sending meeting invitations: It's perfectly acceptable to ask, “Why am I invited?” Likewise, when you send an invitation out, clarify why you're having a meeting, why these people are invited, and what you expect them to contribute in the meeting.

- When you see something you don't understand: As in, “Why did they do that?”

- When someone asks you for something: Ask, “Why are you asking for that?”

- When someone says, “We can't do that”: Ask, “Why can't we do that?”

Summary of Takeaways

Asking why helps you get clarity on your headscratcher by allowing you to:

- distinguish this from that;

- find a root cause;

- get to the I don't know and the things you have to find out; and

- determine whether it's a because!!

It might take 50 words the first time you use why, because you may have to explain why you are even asking. However, once others understand you are in critical thinking mode (headscratching) and appreciate the value of asking why, you can use a single, but powerful “Why?” It is the knowledge gained from the answers to why that helps you create solutions to the actual problem, issue, goal, or objective—the headscratcher.

Exercises for Why

- Take out your to-do list and look closely at each item. Ask why you have it on your list. Once you answer the question, ask, “Are the items on my to-do list the only things I have to complete to fulfill my why for doing them?”

- Do you have a list of requirements or specifications for a deliverable you are committed to? Do you know why those requirements are on that list?

- Look at your goals. Why are these the goals you've chosen?

- The next task you ask someone—a peer, subordinate, or family member—to do, explain why you are asking. Give him or her the opportunity to question why you want it done.

- The next time you find yourself explaining to someone how to do something, think about why you do it that way. You may find no reason, other than you've done it that way before.

- Look at the meetings to which you have been invited on your calendar. Do you know why you are invited, what is expected of you, and why the meeting is being called? If you called the meetings, do all the participants know why they were invited?