Chapter 14

Organizing Participants to Learn from Each Other

The trend over the last 30 years in the training of managers is towards increasingly participative forms of learning. The most common training mechanism used is that of getting participants to work together in small groups or teams or, as they are commonly termed, breakout groups. This trend is more marked in the western world than it is in the east, but the progression globally is towards a greater proportion of each training event involving participants in doing rather than listening.

This should be seen as good news for trainers and participants alike. For participants it means that those who have a preference for Activist forms of learning (see Chapter 3), there is a greater part of most training events that suits their preference. For those with the other three learning style preferences it means that, having listened to the trainer explain the theory and having had the opportunity to discuss it, there is also the opportunity to put the new knowledge into practice during the training event to gain confidence in its use.

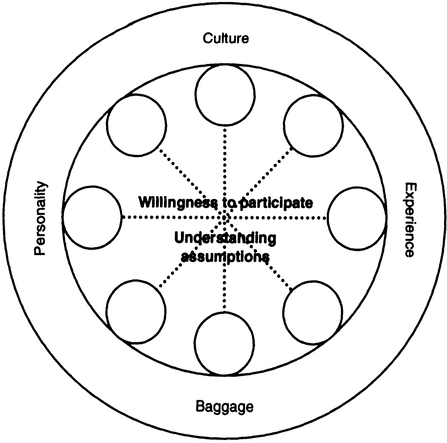

The general way that participants interact in breakout groups can be viewed as a combination of three factors - the background from which they emanate, the baggage that they bring with them to the training course, and the dynamics of their interpersonal behaviour (see Figure 14.1).

Figure 14.1 Participant interactions

What they bring with them from their workplace and private lives is their culture, experience, personality and any baggage, which may be positive or negative.

During the training they will be influenced by each other's willingness to participate, their ability to understand what is being said and what is being meant, and the tacit assumptions each makes about the other's culture.

The current trend for work carried out in breakout groups has four principal challenges for trainers of international managers. The clearest challenge is whether the participants will be able to understand each other. The majority of training that involves multiple nationalities of participants is carried out in English. Work in breakout groups requires the ability to speak as well as understand English reasonably well. A second challenge is that some participants may be less willing to participate and contribute to group activities than others. This becomes particularly evident when using methods such as role play, where participants are asked to put themselves in a particular and often unfamiliar role to practise a new approach that has been introduced by the trainer. A third challenge is that some breakout work requires participants to organize themselves into teams, with a co-ordinator to allocate tasks and a spokesperson to feedback the group's findings to the plenary group. Depending on the characteristics of the group there can be challenges with its willingness to appoint a co-ordinator to allocate tasks and a spokesperson to feed back to the plenary group in English. A fourth challenge is understanding the cultural assumptions each person is making. For example, a Pakistani delegate at one training programme became extremely angry and upset towards a French participant who, in sheer frustration at the group's lack of progress, shrugged his shoulders, looked up to heaven and turned his back towards him.

Breakout groups in practice

In mono-cultural courses participants generally form breakout groups very readily, although the group dynamic will still impact on the outputs achieved. However, with multi-national participants the trainer cannot assume that participants will as easily begin to work together in breakout groups. With these challenges to address it is good practice, particularly on courses that are to be attended by relatively young or inexperienced managers, for the trainer to deliver a fairly undemanding exercise to the breakout groups initially, making the appointment of a co-ordinator less important and demanding only the simplest of feedback. The objectives of this activity are to allow participants to become used to working with each other in an unsupervised group.

On a course that we have run regularly with around 20 young international managers from ten different Western and Eastern European countries, a significant element of the five-day event has involved work in groups of around five participants each. As most of them will not have worked with so many different nationalities before, it is useful to arrange a relatively simple and amusing, yet challenging, team-working exercise initially so that they can begin to get used to each other. The exercise we have used most often requires members of the group to share information that they are each given, structure this information and develop a simple methodology to solve a problem that has only one correct answer, thus appealing to cultures with higher uncertainty avoidance ratings.

Another way of accomplishing more effective teamworking involving a mixture of nationalities is to get the breakout groups to discuss the most significant issue each faces in their own organizations regarding the topic of the course and report back on the similarities and differences that are apparent.

Participants regularly give very positive feedback about this initial work that they do together, saying how effective it is in breaking down any potential barriers between them. It also accustoms the participants to completing a task within a pre-determined time-scale, a key discipline with any breakout work.

Important guidance for organizing successful breakout groups

Participants on international courses not only have the opportunity to put new knowledge into practice in breakout groups, but also have the opportunity to learn from each other if the breakout tasks are well conceived and organized.

Some of the imperatives of effective breakout organization for a training event involving a mixture of nationalities are as follows.

Imperatives

Ensure that there is as good a mixture as possible of the nationalities represented in the group as a whole within each breakout group. If possible, it is also beneficial to mix representatives from all the different functions that may be present on the course and to mix genders as well.

While the plenary group is still together, give very clear instructions about the objectives of the task to be completed and the time by which it must be finished. Be specific in terms of the outputs you are looking for. It is important that this is done before the participants go into their breakout groups, so that everyone involved in the training event has an equal opportunity to hear the answers given to any questions that are asked to clarify the task. In the instructions it is important to stress that participants should consider solutions that have a global application (unless a particular local application is specified), if there is to be value in the feedback for participants from many different countries.

Wherever possible, give every participant a written copy of the objectives of the task, the outputs required and the time allowed for completion. These instructions should also include clear guidance on what is expected in terms of feedback from the group, whether a spokesperson should be nominated and how long the feedback should take. It is also extremely useful with groups working in their second language to encourage them to write up the main points of their feedback on flip-chart paper and use illustrations wherever possible so that they use this as a visual aid when the spokesperson is giving feedback. Other participants, in an international event, listening to the feedback will find it much easier to follow if each spokesperson uses this type of visual aid.

Breakout groups need their own space in which to work, whether it is at separate tables within the main training room or in separate breakout rooms. Naturally, each group also needs its own flip chart and other presentation materials.

A well-constructed breakout task for international groups will have the objectives clearly stated on one side of a piece of A4 paper. Any information required to complete the task should also be clearly laid out and should be sufficiently brief that it does not take a person, working in a second or third language, more than 10 per cent of the total time allowed for the exercise to read and absorb it.

Facilitators should circulate around the breakout groups with the objective of clarifying each participant's understanding of the task and of the information provided. Facilitators should not get involved in the group's team-working processes except to answer very specific questions, and should not help groups solve problems involved in the task unless they are really unable to make a start. There is a particular challenge for the trainer where the breakout group chooses to work in an unfamiliar language. In these circumstances it is probable that the only effective input the trainer can make is to ask the group if there is any need for clarification of the task. Occasionally it may also be beneficial for the trainer to be present when the group is writing feedback points on flip-chart paper if participants need any help in structuring that feedback.

An example of a well-constructed breakout exercise

Figure 14.2 is an example of an exercise used in a course for young international managers from a major consumer goods multi-national. The exercise is part of an introduction to marketing, based around a case study of one of the company's recent product launches.

The objectives of the exercise are concisely expressed; the background information has just been given in a 45-minute presentation, hard copy of which was given to participants on the previous evening, so that those less familiar with this type of marketing challenge could spend more time absorbing the information.

Figure 14.2 Breakout exercise

Effective exercises for breakout groups

The very best exercises are up-to-date case studies that require the participants to solve the type of problems they will encounter on returning to their jobs. If the exercise can be designed so that participants have the opportunity to use a model or process that has been introduced by the trainer, the session will score even more highly in terms of its relevance to their needs.

The exercise in Figure 14.2 was produced in conjunction with a case study, which focused on brand activation in a multi-national company where the emphasis was focused on the need to take products that had been successful in one part of the world and launch them effectively in other parts of the world with relevant local support and initiatives. The case was built by giving participants market information about the new part of the world where the product was to be launched, information about the product itself and then setting a number of tasks which replicate the tasks that would have to be carried out by local activation teams. In this case there were four breakout groups of six participants, with each group having one unique exercise to do and one exercise which was common to all four groups. The benefit of the unique exercises is that the feedback session is full of variety, with each group feeding back on a different question.

Clearly there is significant investment in preparing bespoke case studies and exercises such as this. The pay-back on the investment comes from the relevance and currency of the learning. The case can be updated as the actual launch proceeds, building-in new exercises to replicate some of the situations encountered in the real marketplace and comparing the participants' recommendations with the actions that were taken in practice.

Another type of exercise that is more difficult to manage but can be extremely effective is the role-play situation. This is particularly relevant to training events where there is a significant emphasis on participants developing effective personal behaviours such as in managing or selling. Just as with the case study described above, role plays can be constructed to replicate real situations; in this case, situations encountered by the participants themselves at their places of work. A good example would be coaching skills where participants have been introduced to a coaching model by the trainer and now have the opportunity to learn how to use it in a role-play situation. With a mix of nationalities it is important that the trainer takes account of the factors described in Chapter 2 on cultural diversity when dividing the group into pairs for role-play purposes. Asking two participants from countries with very different power distance cultures to practise coaching skills, for instance, is only valid if they are likely to encounter this cultural challenge in the workplace. Role plays of this type can work equally well with CCTV feedback to the participants or with a third participant acting as observer. The trainer needs to take account of any anxieties that either method could cause the participants and, if there is uncertainty about that, to consult the participants on their preference. Where the video feedback is to be reviewed by the whole group, it is important to ask participants to use the 'course language' for the exercise, rather than their local language, which will not be understood by the trainer or, in many cases, by the other participants. Where participants do use a language with which the trainer is not familiar and there is no translator present, any intervention from the trainer is restricted to comments on body language (which again is often culturally specific) and questions of the participants about the learning they have achieved and their feelings during the role play.

The dynamics of breakout groups

Individual personality is an important dimension that affects the way groups behave, irrespective of culture. In addition, with international managers the dynamics of breakout groups will also, as shown in Figure 14.1, depend on the individual's willingness to participate, their ability to understand what is being said and what is being meant, and the tacit assumptions each makes about the other's culture. The possibility for conflict is therefore multiplied with multi-national courses. Such conflict can have many causes. Cultural misunderstandings have already been touched on. Participants also bring along baggage from their private and work lives and even acquire more during the training itself.

When conducting a residential programme in rural Holland attended by the sales director and his senior and middle managers from around Europe, the participants were encouraged to use the rather splendid sporting facilities to de-stress themselves at the end of the full training days. The sales director saw this as a great team-building opportunity and organized competitions of one sort or another every day in which he also participated and most of which he won. Naturally this caused resentment amongst some participants, and comments such as 'typical of him' and 'he's so busy winning he's no time for living' were muttered in the bar and corridors.

Trainers rarely need to become involved in helping groups resolve these problems, and it is better that groups are allowed to find their own ways of working together effectively. However, sometimes, as in the above case, it can threaten to derail an entire course and the trainer needs to take action. This can be by speaking quietly to the offending individual or, if this is unlikely to work, then calling a time out and, adopting a facilitator role, ask the group including the 'problem' participant, to identify any issues that are inhibiting them getting more out of the learning experience.

Generally it is advisable to change the composition of the groups regularly for events of two days and longer. It is good practice to tell participants in the introduction to the course that the membership of groups will be changed each day or after two days. The reason given should be to give participants a good opportunity to work with different people during the course, while working long enough with one group to develop an effective way of working. This will reduce the likelihood of members of a group becoming embroiled in any sort of serious conflict.

On one occasion on a programme involving participants from over 20 countries it was apparent that one individual from a Middle Eastern country was particularly forceful and opinionated. Unfortunately, the points that he made rarely had anything to do with the particular subject being discussed. This naturally proved extremely disruptive to the group who did not understand that this was his way of establishing his relative status and that after suitably acknowledging the 'perceptiveness of his comments' that they could then ignore them. By changing the composition of the groups every day the disruption was minimized and each individual got the opportunity to learn a bit more about a particular culture.

It is not our job as trainers to try and explain the particular behaviour of a participant. However, at the end of the day, for example in the evening at the bar or over dinner, if the subject is raised then the participants can be encouraged to discuss it amongst themselves in a constructive manner, including the 'problem' participant, with the trainer adopting a facilitation role.

As the participative elements of training increase, so the management of groups becomes more and more important. As a general rule, trainers should organize international groups to give participants the maximum opportunity for learning from people from different cultures and functions, while keeping their own interaction with the groups to the role of clarifier and adviser unless the whole programme will be derailed, in which case they may need to facilitate a solution.

Summary

The general way that participants interact in breakout groups can be viewed as a combination of what they bring with them to the training course and the dynamics of their interpersonal behaviour. What they bring with them is their culture, experience, personality and any baggage, which may be positive or negative, from their workplace and private lives. During the training they will be influenced by each other's willingness to participate, their ability to understand what is being said and what is being meant, and the tacit assumptions each makes about the other's culture.

In international events, groups should be constructed to mix different nationalities, keeping group sizes, ideally, to no more than six participants. Wherever possible, it is good practice to give the groups an initial task which is straightforward and allows the participants within a group to get to know one another. This and subsequent exercises should be fully explained, with questions taken in the plenary session prior to participants breaking up into groups.

The very best case studies are current, where participants are given the opportunity to address issues similar to those that occur in their jobs and then learn how these issues have been addressed in practice, accompanied by a description of the results. Instructions on the feedback required from groups must be clear, and with groups working in their second language it is essential that feedback is accompanied by the use of visual aids to cover key points, with illustrations wherever possible. The facilitator should visit groups while they are working, but restrict inputs to clarifying the task and giving relevant information.

Action plan

Review an exercise that you have created for a past training course, or one that you have recently created for a future course, and use the checklist in the Action plan to ensure that the way in which the exercise is intended to be used meets all the essential criteria for effective learning, which have been discussed in this chapter.

| Essential criteria for effective learning | Your exercise meets the criteria: Yes/No | How you intend to modify the exercise to meet the criteria |

|---|---|---|

| All necessary information for completion of the exercise is given prior to the breakout | ||

| Instructions given to the participants for completion of the exercise: | ||

| 1. are concisely expressed on one side of A4 paper | ||

| 2. include a statement of the time allowed for the exercise | ||

| 3. give guidance on how feedback should be done | ||

| Groups are no more than six participants strong and each one includes a mix of nationalities representative of all the course members | ||

| Time is allowed in the plenary group to answer questions and clarify issues relevant to the exercise |