Media Ownership: Diversity Versus Efficiency in a Changing Technological Environment

Gillian Doyle, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK

Abstract

The role of media – whether television, newspapers, radio, or the Internet – in supplying the ideas that shape our viewpoints and cultures is such that the dangers that may accompany concentrations of ownership in this sector are well recognized. Ownership patterns affect not only pluralism, but also how well the media industry is able to manage its resources and so, in turn, the efficiency and economic strength of this sector. Everywhere they take place, public policy debates around which configurations and what level of ownership of media ought to be permissible are a site for conflicting viewpoints. Some suggest that the greater choice made possible by advances in digital technology and changing patterns of consumption obviate the need for restrictive interventions. However, despite digitization and the growth of the Internet, gravitation towards monopoly remains a marked feature of the industry and, as explained in this chapter, the need for diverse ownership of predominant traditional media remains a concern. A new era of consolidation and cross-platform expansion by established and emergent media players presents regulators with complex and difficult challenges. In examining the economic motives that drive strategies of expansion in the media, this chapter highlights the tension between, on the one hand, sociocultural concerns associated with media empire-building and, on the other hand, economic and industrial policy priorities surrounding media ownership.

Keywords

Media industry; Media ownership; Convergence; Freedom of speech; Media diversity

JEL Classifications Codes

L13; L82; Z10

14.1 Introduction

The United Kingdom is said to have encountered ‘a Berlusconi moment’ recently (Sabbagh, 2010) – in other words, a moment where one proprietor gets a chance to establish a position of unparalleled dominance within the media. That term was used to describe a proposal from News Corporation in November 2010 to acquire the remaining 61% not already owned by the company of the dominant satellite television operator in the United Kingdom, BSkyB. At a time of declining revenues for print media, such a deal would extend News Corporation’s potential access to growth opportunities in pay-television markets. However, the proposed bid was seen by many as potentially damaging to the public interest because, in addition to BSkyB’s dominance in the UK pay television market, the company is a major provider of news to commercial radio stations across the United Kingdom and also its parent company, News Corporation, owns press titles that in 2011 collectively accounted for a share of the UK national newspaper market of some 37% (Fenton, 2011a).

The News Corporation/BSkyB case exemplifies how, not least in times of technological change, patterns of corporate media ownership are shaped by economic and strategic factors. As digitization has encouraged greater cross-sectoral convergence, the emergence of new benefits and gains associated with cross-media ownership has provided an extra spur towards strategies of diversification and cross-sectoral enlargement in the media industry. Even so, and despite the transition to a more web-connected era, concerns remain about the power wielded by dominant media organizations in relation to production and circulation of news, ideas, and cultural and political values within contemporary societies.

In examining the economic issues surrounding media ownership, this chapter seeks to highlight, on the one hand, the tension between sociocultural concerns associated with media empire-building and, on the other hand, economic and industrial policy aspirations surrounding media ownership configurations. The chapter starts in Section 14.2 by examining how changes in technology have impacted on the landscape of media provision and in turn reshaped some of the considerations underlying ownership regulation. Section 14.3 focuses on the main economic motives that drive strategies of expansion and concentrated ownership in the media and the differing forms these strategies may take. The concept of pluralism and the necessity for curbs on excessive concentrations of ownership are explained in Section 14.4. Section 14.5 provides a critical assessment of the complexities and challenges inherent in designing a framework of regulation for ownership of media that weighs up the differing interests at stake effectively, bearing in mind lessons offered by the handling of the News Corporation/BSkyB case in the United Kingdom.

14.2 The Effects of Changing Technology

The introduction of digital technology and growth of the Internet have altered the media landscape irrevocably in recent years, blurring sectoral and geographic boundaries, changing audience consumption behaviors, and transforming levels of revenue and resourcing across the media industry. These changes have reshaped the context in which national frameworks for regulation of media ownership are conceived. In order to be effective, systems to protect media plurality must remain in step with advancing technologies (Foster, 2012). National systems of regulation to protect pluralism do certainly evolve over time; however, because they still focus predominantly on ownership of television, radio and newspapers, some might argue they are insufficiently attuned to recent important changes in the media environment.

14.2.1 Shifts in Audience Behavior

One of the most significant changes affecting media and communications worldwide since the 1990s has been growth of the Internet and in the numbers of people becoming ‘connected’ via fixed broadband and/or mobile. Data assembled by UK communications regulator Ofcom (2010b, p. 4) confirms that:

… there are now around six mobile connections for every ten people, and the new devices and services such as smartphones, digital video recorders (DVRs), high-definition TV and a whole raft of online services are dramatically changing the way consumers all over the world communicate with each other and consume media content.

Related to these trends, it is clear that patterns of media consumption are changing, with readership of print media in decline, more time being spent online and increased use of mobile devices, including for purposes of mobile reception of news (Albarran, 2010). Data from Ofcom confirm that, despite the ongoing popularity of radio and television, the average amount of time spent each day using the Internet and mobile devices has increased substantially in recent years: people in the United Kingdom spent on average 27 minutes per day on fixed Internet connections in 2009 compared with 12 minutes in 2004; similarly, time spent on mobiles has more than doubled in this brief period (Ofcom, 2010a, p. 19). New trends in consumption are reflected in changing attitudes towards which media activity people say they would miss most, with survey research focused on UK adults confirming that the value attributed to reading of newspapers and magazines is in decline while ever more value is attached to use of the Internet. Whereas in 2005, 8% of consumers said the media activity they would miss most is using the Internet, by 2009 this had risen to 15% (Ofcom, 2010a, p. 21).

The introduction of digital technology and growth of the Internet have altered the media landscape irrevocably, blurring sectoral and geographic boundaries, changing how content is produced and distributed, and ushering in more competition at every level of provision. A rise in ‘citizen journalism’ and in the dissemination of user-generated content provide examples of how these developments have extended diversity within media content. However, while consumer choice has been widened, recent survey data for the United Kingdom indicate that those categories of websites that are most popular and have the highest reach with Internet users are not news sites, but rather ‘search and communities’ (Ofcom, 2010a, p. 263). International data also confirm that use of search engines such as Google, engagement in member communities such as Facebook and MySpace, and watching video clips on YouTube are, for most, much more popular activities than trawling the Internet for news (Nielsen data at BBC (2010)).

14.2.2 Repercussions for Advertising Expenditure

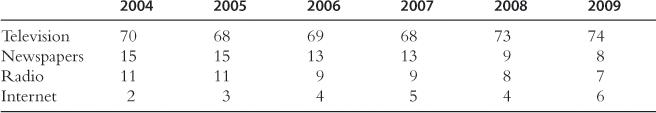

An ongoing migration of audience attention towards the Internet has been accompanied by major shifts in patterns of advertising expenditure. Trends in advertising have historically tended to reflect the performance of the economy at large with pronounced growth in overall levels of advertising expenditure during economic boom periods but swift contraction in periods of recession (Doyle, 2002a, p. 47). The association between economic cycles and levels of advertising activity was confirmed by growth in advertising markets in the United Kingdom from 2004 to 2008 and by a reversal of this trend coinciding with the global economic downturn in 2009 (Warc data cited in Ofcom (2010b, p. 21)). However, while total investment in advertising is strongly influenced by the ups and downs of the economy, one striking new trend in recent years has been growth in expenditure on advertising on the Internet, as shown in Table 14.1.

Table 14.1

Global advertising expenditure by medium (£ billion).

Source: Warc data in Ofcom (2011, p. 20).

Since the start of the twenty-first century, the share of advertising accounted for by the Internet has grown steadily at the expense of all other media including radio, but especially newspapers and magazines. The switch to online has advanced more quickly in the United Kingdom than elsewhere and in 2009 the Internet accounted for a 27% share of UK expenditure (Ofcom, 2010b, p. 24). Growth in Internet advertising has been driven partly by the development of new online intermediaries, including especially search engines such as Google, and also news aggregators and social networking sites that, while well placed to capture and direct the attention of online audiences, may not themselves be re-investing to any significant extent in media content production. This has raised difficult questions for traditional media suppliers and regulators about the future economic sustainability of some forms of content production, especially news journalism (OECD, 2010, pp. 78–79).

A shift in advertising towards the Internet has drawn revenues away from other media and especially newspapers. Local newspapers, which tend to rely heavily on classified advertisements (i.e. advertisements for property, jobs, and motor cars) for a large proportion of their income, have suffered most from the migration of revenues to online competitors (Ofcom, 2009a, p. 30). For many newspaper publishers who until recent years have been profitable, ‘the economics of news production and distribution has been radically altered, in particular in the context of the economic crisis which has accelerated structural changes’ (OECD, 2010, p. 6).

The difficulties confronting the newspaper industry as readership and revenues have declined and at a time of recession have encouraged calls from many publishers for deregulation of cross-ownership restrictions that are seen as impeding the sector’s ability to adapt successfully to changing industry circumstances (Barnett, 2010). In the United Kingdom at least, such calls have not gone unheeded. Following on from a recommendation from Ofcom to do so (Ofcom, 2009b, p. 1), the UK Government in 2010 approved the dismantling of cross-media ownership rules, which had been established to protect pluralism at the local level because of the perceived need to address the economic woes of local media players and in order to allow them greater flexibility to evolve into ‘a new generation of multi-media content providers’ (Sweney, 2010).

14.2.3 Predominant Sources of News

While the Internet has become an increasingly significant source of news over recent years, especially for younger audiences, it is worth remembering that for most Internet users online news sources serve only as a complement rather than a substitute for conventional news media (Ofcom, 2010c, p. 13; OECD, 2010, p. 9). Despite the growth of the Internet, most people still derive their news and views from traditional media platforms. Indeed, in arguing that local cross-media ownership rules should be liberalized in order to ensure the economic viability of ‘an industry facing difficult market conditions’, UK regulator Ofcom was at pains to emphasize that audiences are still reliant to a surprising extent on television, newspapers, and radio as their main sources of news (Ofcom, 2009b, p. 1), as shown in Table 14.2.

Table 14.2

UK adults’ main source of news (%).

Source: Data from Ofcom Media Tracker (Ofcom, 2009b, p. 16).

Given that most people still continue to consume news via traditional sources, it is fair to argue that protections for pluralism must still ensure access to a diversity of viewpoints on these popular traditional platforms. A predominant focus, within national systems of regulation on maintaining plurality of ownership of television, radio, and newspapers, is still justified. Even so, growing use of the Internet has engendered changes in media supply and consumption habits that clearly will, over time, pose new challenges for policy makers. Many of the players who have dominated traditional media are migrating their operations onto new platforms, and meanwhile the rise of search and intermediation have introduced powerful new players and potentially worrying new forms of dominance over access points to media (Foster, 2012). In the United Kingdom, Google eclipsed commercial television broadcaster ITV to become the largest earner of advertising revenues in 2007 and the company continues to dominate search marketing, which accounts for a majority of all online advertising (Bradshaw, 2009). While new online services flourish and traditional media suffer marked declines in audiences and revenues, regulators and policy makers have been confronted by growing arguments from newspaper and broadcasting proprietors to get rid of remaining ownership restraints that may impede the expansion strategies needed to take advantage of economic opportunities offered by the digital era (OECD, 2010, p. 78).

14.3 Concentrated Ownership and Economic Performance

A variety of reasons may explain why concentrations of ownership are a widely evident feature of media industries worldwide and only some of these are economic. Given the potential for ownership of newspapers and other media to translate itself into political influence, it may well be that strategies of expansion and empire-building in this industry are sometimes driven by motives that have little to do with profit maximization. However, a considerable body of research exists to suggest that large-scale ownership of media enterprises is motivated by a number of economic gains, advantages, and benefits (Albarran and Dimmick, 1996; Doyle, 2002a; Picard, 2002; Vukanovic, 2009). This section explores the economic motives for expansion in more detail.

14.3.1 Natural Monopoly Tendencies in the Media

The prevalence of concentrations of ownership in the media owes much to the unusual public-good qualities of media content as a commodity and, associated with this, the fact that making content is typically characterized by high initial production costs, but low marginal reproduction costs (Collins et al., 1988; Blumler and Nossiter, 1991). Like other information goods, media content is not really consumable in the same way as other normal goods (Withers, 2006, p. 5). As the main value within media content is generally to do with attributes that are immaterial (i.e. its messages or meanings) and these do not get depleted in the act of consumption, it follows that once the first copy of, say, a television program has been created, it costs little or nothing to reproduce and supply it to extra customers. In other words, the marginal cost involved in conveying a television or radio service to an extra viewer or listener within one’s transmission reach is typically zero, at least for terrestrial broadcasters. Similarly, providing an online media content service to one additional Internet user involves negligible additional costs. Although producing a new book, music recording, or feature film generally involves a substantial investment of sunk costs (Van Kranenburg and Hogenbirk, 2006, p. 334), it then costs relatively little and sometimes nothing to reproduce and supply it to extra customers. So, increasing marginal returns will be enjoyed as the audience for any given media product expands.

These scale economies in the media industry are accompanied by economies of scope; the public-good qualities associated with media content facilitate strategies of re-use of content across ostensibly different products (Doyle, 2002a). For media enterprises, the widespread availability of economies of scale and scope creates natural incentives towards enlargement and cross-sectoral diversification. So, the tendency towards concentrations of ownership that is a well-established and long-recognized feature of media industries may be regarded as an unavoidable corollary of the basic economic characteristics of the sector.

14.3.2 Convergence and Globalization

In addition to the above natural incentives towards expansion and monopolization, recent advances in technology have amplified many of the advantages that makers and suppliers of media content can reap as they extend or spread the consumption of their output across additional consumers, thereby yielding enhanced economic benefits to large-scale and diversified media organizations. Spurred on by digital convergence and dramatic growth in the borderless distribution infrastructure for media that is the Internet, the traditional boundaries surrounding media markets are gradually being eroded (Küng et al., 2008). Media and communications industries have been strongly affected by globalization, and by increasing competition at home and abroad for audience attention and for advertising revenues (Hollifield, 2004; Sánchez-Tabernero, 2006). Thus, advancing technology has played a role in diminishing traditional geographic market boundaries, but also technology – more precisely convergence – has served to blur the perceived boundary lines surrounding and separating different sorts of media products and markets.

The term ‘convergence’ is used in many different ways (Jenkins, 2006), but in the current context it is intended to denote the coming together and use of common or shared digital technologies across all media and communications industries, and in all stages of production and distribution of content. Sectors of industry that were previously seen as separate now overlap with each other because of the shift towards using common digital technologies. These forces are widely recognized as of major importance in affecting industry structure (Drucker, 1985, pp. 75–76). Convergent technologies have spurred on the development of digital platforms, new forms of content, and of converged devices, impacting not only on content and delivery, but also, as many earlier studies have shown, on the operational and corporate strategies of media organizations (Doyle, 2002b; Küng, 2008). Convergence has drawn players from the broadcasting, telecommunications, and IT sectors into each other’s territories. Owners of high-capacity communication infrastructures are increasingly interested in media content businesses (and vice versa) and in the commercial possibilities surrounding provision of multimedia, interactive, and other new media services in addition to conventional television and telephony (Terazono, 2006). Owing to the potential for economies of scale and scope, the greater the number of products and services that can be delivered to consumers via the same communications infrastructures, the better the economics of each service.

Expansion is, of course, always accompanied by risk. Challenges associated with enlargement can and do sometimes cause serious problems for media firms who, in the process of expanding, lose their focus and momentum (Sánchez-Tabernero and Carvajal, 2002, pp. 84–87). Nonetheless, strategies of enlargement and diversification in the media often make a great deal of economic sense. Highly concentrated firms who can spread production costs across wider product and geographic markets will benefit from natural economies of scale. Enlarged, diversified, and vertically integrated groups appear well-suited to exploit technological and other market changes sweeping across the media and communications industries.

14.3.3 Differing Forms of Expansion

Strategies of corporate growth and associated economic advantages can be assessed under at least three general categories: horizontal, vertical, and diagonal expansion. Looking first at horizontal growth, the desire to capitalize on economies of scale is the classic incentive underlying such strategies in general (Griffiths and Wall, 2007, p. 79) and, in media industries, is an obvious motivating factor. Not only can media companies that do business in the same area benefit from joining forces through, for example, applying common managerial techniques or through greater opportunities for specialization of labor as the firm increases in size, but, in particular, horizontal expansion allows firms in the media sector to capitalize on economies of scale (Hoskins et al., 2004, p. 97).

Vertically integrated media firms may have activities that range from creation of media output (which brings ownership of copyright) through to distribution or retail of that output in various guises. As originally identified by Coase (1991), one of the chief incentives towards vertical expansion is the possibility of reduced transaction costs for the enlarged firm. However, another benefit that in the case of media players is often of great significance is that vertical integration gives firms some control over their operating environment and it can help them to avoid losing market access in important upstream or downstream phases (Martin, 2002, pp. 405–406). Broadcasters who own program production businesses have more secure access to the content they need and, by the same token, vertical integration into distribution gives content producers assured access to audiences. Integrated media firms are better placed to avoid the market power of dominant suppliers or buyers in other parts of the vertical supply chain (Aris and Bughin, 2009, p. 271).

Diagonal or ‘conglomerate’ expansion is another common strategy in the media. For example, a merger between a telecommunications operator and a television company might generate efficiency gains as both sorts of services – audiovisual and telephony – are distributed jointly across the same communications infrastructure (Albarran and Dimmick, 1996). Newspaper publishers may expand diagonally into television broadcasting or radio companies may diversify into magazine publishing. A myriad of possibilities exists for diagonal expansion across media and related industries. Such strategies often create economic gains and synergies, but not necessarily so (Peltier, 2004). One possible benefit is that it helps to spread risk (Picard, 2002, p. 193); large diversified media firms are, to some extent at least, cushioned against any damaging movements that may affect any single one of the sectors they are involved in. Most importantly though, diagonal expansion in the context of the media industry is strongly motivated by the widespread availability of economies of scale and scope.

In response to digital convergence, many if not most sizeable media firms are now seeking to re-configure their operations – often through expansions and acquisitions – in order to adopt a multiplatform outlook (Doyle, 2010). In the television industry, for example, this has been characterized both by the introduction of ‘360-degree commissioning’ (Parker, 2007), and the development of websites and other digital offerings capitalizing on popular content brands. A 360-degree approach means that new ideas for content are considered in the context of a wide range of distribution possibilities and not just the linear television transmission. It implies that, from the earliest stages of conceptualization, content decisions are shaped by the potential to generate consumer value and returns through multiple forms of expression of that content and via a number of distributive outlets (e.g. online, mobile, interactive games, etc.) including, but also moving beyond, conventional television or newsprint.

There are at least two important ways in which multiplatform expansion can significantly improve economic performance (Doyle, 2010). First, strategies of re-versioning of content into new outputs and of re-use of it across new platforms can and do enable greater value to be extracted from intellectual property assets. In other words, sharing content across different formats and platforms gives rise to economies of scale and scope, albeit that the risk of illegal copying and intermediation is clearly an important concern in relation to Internet distribution of media content. A second area where digitization and multiplatform distribution provide opportunity for innovation and improved efficiency relates to the unprecedented ways that new technology allows media suppliers to get to know their audiences and to match up content more closely to their needs and desires. Owing to improved signaling of audience preferences via the digital return path (Webster, 2008), the ability of content suppliers to trace, analyze, monitor, and cater more effectively to shifting and specific tastes and interests amongst audiences has vastly increased. In addition, because of the ‘lean forward’ rather than ‘lean back’ character of digital media consumption, a much more intensive relationship with audiences can be constructed, and again this is a source of both creative and commercial opportunities.

In addition to cross-platform expansion, many media firms such as Viacom, Lagardère, and News Corporation are or have become multinationals. Encouraged by growth of the Internet, greater mobility of international capital, and generally lower barriers to international expansion, many media operators have looked beyond the local or home market for ways to expand their consumer base horizontally and thereby extend their economies of scale. For example, EMAP acquired several magazine publishing operations in France in the mid-1990s and became the second largest player in that market before itself being taken over in 2007 by German publishing giant Bauer. French media group Vivendi Universal has, through Canal+, established a predominant position in many pay-TV markets across Europe. German and Scandinavian media groups such as Bonnier, Bertelsmann, Sanoma, and Schibsted have been active in expanding their activities into other countries. Examples of media companies seeking to extend their operations across frontiers are abundant and this trend has in some cases contributed to a strengthening in the position of dominant players in regional markets, such as South America and East Asia.

The basic rationale behind all such strategies of enlargement is usually to try and utilize common resources more fully. Diversified and large-scale media organizations are in a good position to exploit common resources across different product and geographic markets. This is not to deny the potentially numerous difficulties and challenges associated with management of enlarged and multifaceted enterprises (Sánchez-Tabernero and Carvajal, 2002, pp. 84–87). In terms of profits performance, the financial pitfalls and managerial complexities associated with expansion and diversification may sometimes outweigh any economies of scale and scope (Kolo and Vogt, 2003), at least in the short term. Even so, the key point is that strategies of expansion and diversification in the media sector are usually supported by an economic logic that, on account of the spread of digital technologies, has become even more compelling. Large, diversified, and transnational entities are better able at least potentially to reap the economies of scale and scope that are naturally present in the media industry and that, thanks to globalization and convergence, have become even more pronounced.

14.4 Sociocultural Implications of Media Ownership

14.4.1 Pluralism and Freedom of Speech

The economic and commercial advantages that accrue as media firms enlarge and diversify help account for trends towards concentrated ownership that are evident in many if not all countries around the globe. Why do we need to be concerned about concentrations of media ownership? Such concerns stem from a perceived need to preserve pluralism, which in turn is often regarded as stemming from the more fundamental issue of freedom of expression as enshrined within the Convention on Human Rights. Pluralism is a somewhat vaguely defined concept (Karppinen, 2007; Ofcom, 2010c), but it generally embodies the idea of public access to a range of voices and a range of content (Doyle, 2002b, p. 12). Pluralism is a separate concept from freedom of expression, but the two are related in that access to differentiated sources of media is often regarded as an integral aspect of free speech. The Council of Europe, for example, which has long taken an interest in monitoring media concentrations within member states, does so on the basis that the need for pluralism is closely associated with the need for freedom of expression, a matter for which the Council is responsible (Lange and Van Loon, 1991, pp. 13–26). The view generally taken is that ‘[m]edia pluralism is the key that unlocks the door of freedom of information and freedom of speech. It advances the ends of freedom of speech by facilitating a robust marketplace of ideas’ (Haraszti, 2012, p. 102). Without an open and pluralistic system of media provision, the rights to receive and to impart information, which are seen as part and parcel of the right to free speech, might well be curtailed for some individuals or groups within society.

The concept of pluralism in this context embraces both diversity of ownership (i.e. the existence of a variety of separate and autonomous media suppliers) and also diversity of media output (i.e. varied media content) (Doyle, 2002b, p. 12). This distinction is sometimes denoted by use of the terms ‘external’ and ‘internal’ pluralism, the latter – diversity of content – being addressed through regulatory measures aimed at encouraging diversely sourced, unbiased output. A further distinction can be made between ‘political’ and ‘cultural’ pluralism (Valcke et al., 2010). The former refers to the need for a range of viewpoints and political opinions to find expression in the media in order to preserve the health of democracy. ‘Cultural’ pluralism, on the other hand, refers to the need for the variety of cultures present within society to be reflected within the media. The importance of valuing and protecting cultural diversity was underlined by the adoption of the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions1 in 2005. This signaled a widespread and growing recognition that, in the interests of sustaining social cohesion, it is important that the cultures and values of all groupings within society (e.g. those sharing a particular language, race, or creed) can find expression, including within the media. Growing awareness of the threats posed by media empire-building in the context of preserving diversity and plurality has led to a renewed international interest in modes of monitoring, measuring, and curbing concentrations of media ownership (Just, 2009; Valcke et al., 2010).

14.4.2 Concentrated Ownership and Pluralism: Cause and Effect

As we have noted, concentration of media ownership in the hands too few individuals or firms is problematic because of ‘the potential risks they pose to diversity of ideas, tastes and opinions’ (Meier and Trappel, 1998, p. 38). Many scholars have focused attention on these risks, including the abuse of political power by media owners or the under-representation of some important viewpoints (Murdock and Golding, 1977; MacLeod, 1996; Humphreys, 1997; Demers, 1999; Baker, 2007). However, it should be acknowledged that in practice surprisingly little empirical research has been carried out to pinpoint the exact cause-and-effect relationship between concentrations of media ownership and pluralism. As observed by Eli Noam, ‘[w]hen it comes to media concentration, views are strong, theories abound, but numbers are scarce’ (Noam, 2009, p. 3). Indeed, the extent to which large and diversified media conglomerates add to or detract from diversity of content and consumer choice is debatable. It is certainly possible that media conglomerates can have a positive impact on diversity of media output; for example, if the scale of resources available to a large firm enables it to invest in innovation or if its financial strength enables it to support or cross-subsidize a temporarily loss-making product (Doyle, 2002b, pp. 23–26). Theoretically, the additional capital and mix of expertise available to large, diversified media conglomerates ought to be advantageous when it comes to launching new products. On the other hand, in a digital media environment, the extent to which innovation of attractive new products and services really requires extensive initial capital investment is open to question; many successful new services such as Facebook are not the outcome of heavy corporate investment. It is also questionable whether monopolistic ownership structures serve to encourage creativity and a risk-taking management culture (Doyle, 2002b, p. 25). The complexities and challenges that beset media organizations as they grow larger are well recognized (Sánchez-Tabernero and Carvajal, 2002), and growth may in some cases impede flexibility and the propensity for entrepreneurship.

In fact, whether a media merger is likely to widen or narrow consumer choice and diversity is largely determined by how the transaction serves to change the way in which the resources involved in content production within the merged entity are organized and managed. If the integration of back-office activities and support functions (e.g. finance) that have no bearing on content production enables resources to be freed up and transferred into better quality and more diverse content, this will impact favorably on diversity and on consumer interests. However, if on the other hand, a merger encourages consolidation and sharing of editorial functions or more recycling of product content, this will harm rather than benefit diversity and pluralism (Doyle, 2002b, p. 24). To the extent that common ownership makes it more feasible or financially more attractive for elements of the same content and editorial approach to be embodied in ‘different’ media products, cross-ownership will impact negatively on diversity.

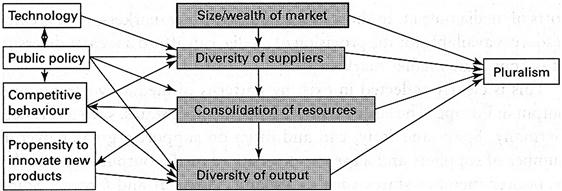

Thus, the relationship between media empire-building and pluralism is somewhat difficult to pinpoint, not least because, as illustrated in Fig. 14.1, the existence of media concentrations is just one (important) component in a much wider framework of interrelated issues that have some sort of impact on pluralism, whether positive or negative (Doyle, 1998, 2002b, pp. 13–29). For example, the size and wealth of a market is one inescapable determinant of how many suppliers there are and what level of diversity within media provision is affordable. The state of technology (e.g. which platforms for distribution are available and how widely accessible they are) is another crucial determinant. A key point is that while concentrations of media ownership and of media power pose a risk of imbalances within the media that threaten democracy and social cohesion, they are not the only factors that have a bearing on levels of pluralism. Hence, ownership rules generally need to be backed up by other measures such as subsidies for minority media, editorial agreements, and support for public service broadcasting.

Figure 14.1 Concentrated media ownership and pluralism. (Source: Doyle (2002b, p. 15).)

14.5 Media Ownership and Public Policy

14.5.1 Economic Efficiency Versus Pluralism

Broadly speaking, concentrations of media ownership impact on two sorts of economic policy objectives: the desire to maximize efficiency and also the need to sustain competition (Doyle, 2002a, p. 167). These goals are related insofar as fair and plentiful competition is seen as a general prerequisite to efficiency. However, a media industry that is too fragmented and does not allow firms achieve the scale and corporate configuration needed to exploit all available economies or to harness the advantages of changing technology is prone to inefficiency. Hence, the two objectives can pull in opposite directions, requiring policy makers to make a tradeoff between tighter restrictions enabling greater competition, on the one hand, and looser controls potentially allowing efficiency to be maximized, on the other. Given the differing interests at stake, it is not surprising that public debate about what sorts of corporate configurations ought to be allowed is often characterized by conflict. From the standpoint of promoting competition where a market is subject to a degree of monopolization, one of the crucial issues is whether that market nonetheless remains contestable. However, whether a market is contestable and whether it is pluralistic are two different matters (Iosifidis, 2005). From the point of view of protecting pluralism, what counts is the actual presence within a market of a diversity of owners thus facilitating the propagation of diverse agendas and viewpoints. Competition legislation is generally regarded as insufficient for this purpose and a poor substitute for curbs specifically designed to prevent unhealthy concentrations of media ownership. While economists can usefully advise on the economic consequences of decision making, it is important to note that ultimately decisions about the tradeoff between protecting pluralism and accommodating the expansionist ambitions of media companies are reliant on the exercise of political judgment.

14.5.2 News Corporation’s Bid for BSkyB

The handling by the relevant UK authorities of News Corporation’s proposal in November 2010 to take full control of BSkyB illustrates many of the challenges faced by media policy makers in seeking to regulate ownership effectively. Such difficulties may include judging how in practice a merger or takeover will impact on allocative efficiency within the merged entity, how exactly diversity of content provision will be affected by changes in ownership, and, from the point of view of sustaining political and cultural pluralism, what level of ownership of media by a single commercial entity should be considered acceptable. In particular, the News Corporation/BSkyB case provided a salutary reminder of the ways in which democracy can be put at risk when frameworks that are supposed to protect plurality prove ineffective in curbing the power of dominant media owners.

One area of concern for Ofcom in looking at News Corporation’s bid to acquire BSkyB was how the transaction might impact on the economic health and sustainability of the media industry (Smale, 2010). The regulator acknowledges the need for regulation to ensure that media companies have ‘the freedom to innovate in response to market developments [and] to make risky investments and earn suitable rewards …’ (Ofcom, 2010c, p. 15). In considering how the deal might impact on future developments, the regulator drew attention to News Corporation’s positive track record of investment in risky new business opportunities; it noted how the company, as a well-resourced and innovative enterprise, may be well placed to develop potentially profitable business models for online delivery of media to extend consumer choice. Thus, blocking the company from adopting the cross-ownership configuration it saw as conducive to exploiting market opportunities could be counter-productive.

However, a countervailing risk associated with the deal was that it might over time result in closer integration of newsgathering operations, and in more sharing of editorial and journalistic resources across the enlarged group, to the detriment of pluralism (Ofcom, 2010c, p. 67). One former BSkyB executive argued in a submission to Ofcom that News Corporation and BSkyB were already able to integrate news production activities should they wish, but had chosen not to do so (Elstein, 2011). Although correct, this viewpoint did not address how increasing economic incentives towards multiplatform production and distribution may encourage different sorts of operational strategies in future (Doyle, 2010). Ofcom received numerous representations to the effect that a merged News/BSkyB entity would, through developing cross-media digital products and services ahead of rivals, be empowered to strengthen over time its existing dominance and share of the UK media voice (Ofcom, 2010c, pp. 82, 84).

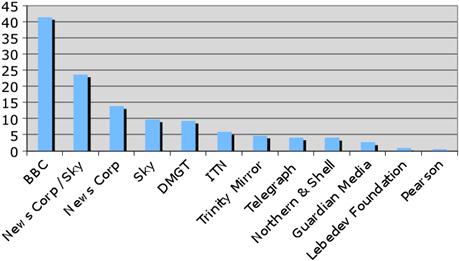

In its deliberations as to whether or not the concerns raised by the transaction warranted a further stage of investigation on the part of the UK authorities, Ofcom stated that its main consideration was how the deal would affect pluralism. In trying to assess the impact, Ofcom looked not just at the number and range of media players but also ‘their relative ability to influence and inform public opinion’ (Ofcom, 2010c, p. 7). Using a measure based on minutes spent consuming news via newspapers, television, radio, and the Internet per person per day, Ofcom arrived at a calculation of the total cross-platform audience share of each of the largest UK media enterprises, as shown in Fig. 14.2.

Figure 14.2 Share of news consumption by media enterprise (%). (Source: Based on data from Ofcom analysis (2010c, p. 58).)

Quantifying the relationship between media ownership and influence is fraught with methodological difficulty, especially when it involves a comparative cross-platform dimension. One acknowledged weakness with Ofcom’s approach was the assumption that a minute of news consumption is equal across all platforms, whereas in reality some would argue that, for example, because television has more immediacy and impact it deserves a heavier weighting (Ofcom, 2010c, p. 57). While the absence of any universally agreed-upon standard measures for media influence is an impediment to analysis of this sort, the calculations that Ofcom produced nonetheless provided an instructive overview of the relative position of the main news suppliers in the United Kingdom in terms of audience share. Ahead of any merger, News Corporation already accounted for a 13.8% share of UK news consumption; if permitted, the acquisition of BSkyB would add a further 9.8%, thus bringing News Corporation’s total share up to 23.7% (Ofcom, 2010c, p. 58). Although disputed by News Corporation itself, broadly similar findings concerning News Corporation’s market share and the gap between it and all other commercial rivals emerged from a separate analysis carried out by independent media consultancy Enders Analysis (Enders and Goodall, 2010, p. 18); this analysis also estimated the audience share a post-acquisition entity would command (22.0%). What level of ownership of a national media landscape is acceptable? No consensus exists on this point, but in the United Kingdom many opposed the idea that an organization which already accounted for a 37% share of the UK national press and a 25% share of consumption of commercially provided news (i.e. excluding the BBC) across the main delivery platforms should be allowed to extend its share of voice any further (Fenton, 2011a).

In the event, Ofcom concluded that the proposed acquisition of BSkyB by News Corporation was likely to operate against the public interest by narrowing media plurality. Its Report called for a further and fuller public investigation to be carried out by the Competition Commission (Ofcom, 2010c). However, this recommendation was not complied with; instead, the UK Culture Minister took the ‘surprise move’ of announcing he would give News Corporation time to bring forward an undertaking that, if successful in alleviating the concerns raised, would enable the proposal to be approved rather than making a referral (Sabbagh, 2011). Some regarded allowing the company a chance to make further representations as an appropriate step towards buttressing the legality of any final decision arrived at (Goodall, cited in Fenton (2011b)). However, for many the Minister’s willingness to negotiate with News Corporation rather than taking a more hard-line stance exemplified a major and well-recognized problem with tackling concentrations of media ownership, namely that ‘the media’s unique influence over politically salient public opinion can make politicians reluctant to fight powerful media owners’ (Hultén et al., 2010, p. 14). It is for this very reason, of course, that policies to ensure diverse ownership remain a crucial safeguard both for democracy and for protection of cultural pluralism more widely.

The deficiencies of the UK framework that is supposed to protect pluralism were highlighted when, during a final week of consultation about the deal, the proposed BSkyB takeover – one that many opposed, but that the Minister was minded to permit – had to be abandoned because a scandal about unethical journalistic practices at News Corporation titles erupted unexpectedly (Ross, 2011, p. 8). The subsequent public enquiry into media practices led by Lord Justice Leveson brought to the fore wider questions about unhealthy relationships between UK politicians and press owners, and the evident ineffectiveness of policies intended to curb excessive ownership (Fenton, 2012, p. 3). It remains to be seen whether the Leveson Inquiry will result in more effective legislative protection for pluralism in the future. A good starting point for reform would be to recognize that, given the central role played by media in contemporary systems of political communication, a statutory regime that relies on the exercise of discretionary powers by a Minister – as does the current UK regime – is far less likely to work than a robust, equitable, and transparent system of structural regulation.

14.6 Conclusions

The spread of digital technology and rise of the Internet are changing media consumption patterns, and, with greater interactivity, are providing audiences with much more control and wider choices about when and how they can use and engage with content. However, while growth of the Internet has opened up increasing avenues for distribution of differing viewpoints, the fact is that mainstream media brands and services still predominate within patterns of consumption. Not only do the majority of us still rely on television and newspapers for our news and views, but even looking towards the Internet as an increasingly important source of media provision, it is notable that ‘10 of the top 15 online providers of news’ in the United Kingdom are dominant traditional media players and the remainder are news aggregators rather than alternative providers of news (Ofcom, 2010c, p. 13). Thus the greater choice made possible by advances in digital technology and the changing patterns of consumption, while welcome developments, do not as yet remove the need for diverse ownership of traditional media (i.e. press and broadcasting).

At the same time, the transition to digital platforms introduces complex new challenges for policy makers seeking to update protections for media pluralism. The rise of search engines, of content aggregation sites, and of social media has introduced new sources of control over access points to content and new forms of influence over which sorts of content and content brands will gain positions of popularity with audiences. Policy makers are also confronted by a new era of consolidation and cross-platform expansion by traditional media players such as News Corporation. Many if not most traditional media suppliers have responded to digital convergence and the Internet by seeking to adopt a strategy of multiplatform distribution. On the one hand, this has multiplied the universe of available media contents and extended the range of opportunities for audiences to engage with such content. On the other hand, to the extent that multiplatform strategies encourage strategies of brand extension and more recycling of content across platforms, additional choice is largely illusory and instead the result is greater uniformity and standardization.

It is widely acknowledged that digital audiences using the two-way interface now enjoy much more control over what content is consumed, and when, than was possible in the analogue era. The extended geographic and temporal access to media content provided by the Internet does, as suggested by Anderson’s long-tail theory (2006), augur well for the ability of suppliers of niche material to exploit their content properties more effectively in the future by selling in small amounts over long periods. However, given the media industry’s fundamental reliance on economies of scale, any notion of a future in which all content is fashioned according to individualized needs would be utopian. Irrespective of digital developments, the business of supplying mass media remains reliant on sharing content production costs across as wide an audience as possible. Hence, gravitation towards monopoly continues to be a feature of the media industry and, concomitantly, the opportunities for individual voices and corporations to dominate are as much of a problem now as in the past. In spite of the new modes of interaction between suppliers and consumers of media, pluralism is not yet a ‘natural’ feature of markets for mass media, nor is it likely to become so in the near future.

References

1. Acheson K, Maule C. Convention on cultural diversity. Journal of Cultural Economics. 2004;28:243–256.

2. Albarran A. The transformation of the media and communications industries. Media Markets Monograph 11 Navarra: University of Navarra; 2010.

3. Albarran A, Dimmick J. Concentrations and economies of multiformity in the communication industries. Journal of Media Economics. 1996;9:41–50.

4. Anderson C. The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More. New York: Hyperion; 2006.

5. Aris A, Bughin J. Managing Media Companies: Harnessing Creative Value. second ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

6. Baker C. Media Concentration and Democracy: Why Ownership Matters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

7. Barnett, S., 2010. What’s wrong with media monopolies? A lesson from history and a new approach to media ownership policy. MEDIA@LSE Electronic Working Paper 18, MEDIA@LSE, London. <http://www2.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/mediaWorkingPapers>.

8. BBC, 2010. Superpower: visualising the Internet. BBC News. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/8562801.stm>.

9. Blumler J, Nossiter T, eds. Broadcasting Finance in Transition: A Comparative Handbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991.

10. Bradshaw, T., 2009. Web beats TV to biggest advertising share. Financial Times, 20 September. <http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/9d2c1d9a-ad23-11de-9caf-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1CtsD8K1x>.

11. Coase, R., 1991. The nature of the firm. Reprinted in: Williamson, O., Winter, S. (Eds.), The Nature of the Firm: Origins, Evolution and Development. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 18–74 (Originally published 1937).

12. Collins R, Garnham N, Locksley G. The Economics of Television: The UK Case. London: Sage; 1988.

13. Demers D. Global Media: Menace or Messiah? Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 1999.

14. Doyle, G., 1998. Media Consolidation in Europe: the impact on pluralism. Report for the Committee of Experts on Media Concentrations and Pluralism (MM-CM), Council of Europe, Strasbourg.

15. Doyle G. Understanding Media Economics. London: Sage; 2002a.

16. Doyle G. Media Ownership: The Economics and Politics of Convergence and Concentration in the UK and European Media. London: Sage; 2002b.

17. Doyle G. From television to multi-platform: less from more or more for less? Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. 2010;16:431–449.

18. Drucker P. Innovation and Enterprise. Oxford: Elsevier; 1985.

19. Elstein, D., 2011. Critics of News Corp’s BSkyB takeover are missing the point. The Guardian: Organgrinder blog, 5 January. <www.guardian.co.uk/media/organgrinder/2011/jan/05/news-corp-bskyb-david-elstein>.

20. Enders C, Goodall C. Ofcom Submission Outline Material. London: Enders Analysis; 2010.

21. Fenton, B., 2011a. Hunt urged to refer bid for BSkyB. Financial Times, 9 January. <www.ft.com/cms/s/0/1bf9d524-1c20-11e0-9b56-00144feab49a.html#axzz1DGjiTnX0>.

22. Fenton, B., 2011b. Hunt delays referral of News-BSkyB bid. Financial Times, 25 January. <http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/f24f9106-2858-11e0-bfcc-00144feab49a.html#axzz1DGjiTnX0>.

23. Fenton, B., 2012. Miliband says Murdoch should lose some papers. Financial Times, 13 June, p. 4.

24. Foster R. News Plurality in a Digital World. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism/Joseph Rowntree Trust Foundation; 2012.

25. Graber C. The new UNESCO convention on cultural diversity: a counterbalance to the WTO? Journal of International Economic Law. 2006;9:553–574.

26. Griffiths A, Wall S. Applied Economics. 11th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education; 2007.

27. Haraszti M. Media pluralism and human rights. In: Human Rights and a Changing Media Landscape. Strasbourg: Council of Europe; 2012;101–132.

28. Hollifield A. The Economics of International Media. In: Alexander A, Owers J, Carveth R, Hollifield A, Greco A, eds. Media Economics: Theory and Practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004;85–106.

29. Hoskins C, McFadyen S, Finn A. Media Economics: Applying Economics to New and Traditional Media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004.

30. Hultén O, Tjernström S, Melesko S, eds. Media Mergers and the Defence of Pluralism. Göteborg: Nordicom; 2010.

31. Humphreys, P., 1997. Power and Control in the New Media. Paper Presented at the ECPR-Workshop New Media and Political Communication, University of Manchester.

32. Iosifidis P. The application of EC competition policy to the media industry. International Journal on Media Management. 2005;7:103–111.

33. Jenkins H. Convergence Culture. New York: New York University Press; 2006.

34. Just N. Measuring media concentration and diversity: new approaches and instruments in Europe and the US. Media, Culture & Society. 2009;31:97–117.

35. Karppinen K. Making a difference to media pluralism: a critique of the pluralistic consensus in European media policy. In: Cammaerts B, Carpentier N, eds. Reclaiming the Media: Communication Rights and Democratic Media Roles. Bristol: Intellect; 2007;9–30.

36. Kolo C, Vogt P. Strategies for growth in the media and communication industry: does size really matter? International Journal on Media Management. 2003;5:251–261.

37. Küng L. Strategic Management in the Media. London: Sage; 2008.

38. Küng L, Picard R, Towse R. The Internet and the Mass Media. London: Sage; 2008.

39. Lange, A., Van Loon, A., 1991. Pluralism, concentration and competition in the media sector. IDATE/IVIR, December.

40. MacLeod V, ed. Media Ownership and Control in the Age of Convergence. London: International Institute of Communications; 1996.

41. Martin S. Advanced Industrial Economics. second ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 2002.

42. Meier W, Trappel J. Media concentration and the public interest. In: McQuail D, Siune K, eds. Media Policy: Convergence, Concentration and Commerce. Salzburg: Euromedia Research Group; 1998;38–59.

43. Murdock G, Golding P. Capitalism, communication and class relations. In: Curran J, Gurevitch M, Woollacott J, eds. Mass Communication and Society. London: Edward Arnold; 1977;12–43.

44. Noam E. Media Ownership and Concentration in America. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009.

45. OECD, 2010. The evolution of news and the Internet. Report by Working Party on the Information Economy, DSTI/ICCP/IE, 2009 14/FINAL, OECD, Geneva.

46. Ofcom. Media Ownership Rules Review. London: Ofcom; 2009a.

47. Ofcom, 2009b. Report to the Secretary of State (Culture, Media and Sport) on the Media Ownership Rules, Ofcom, London.

48. Ofcom, 2010b. Communications Market Report, Ofcom, London.

49. Ofcom, 2010b. International Communications Market Report, Ofcom, London.

50. Ofcom, 2010c. Report on Public Interest Test on the Proposed Acquisition of British Sky Broadcasting Group plc by News Corporation, Ofcom, London.

51. Ofcom, 2011. International Communications Market Report, Ofcom, London.

52. Parker, R., 2007. Focus: 360-degree commissioning. Broadcast, 13 September, p. 11.

53. Peltier S. Mergers and acquisitions in the media industries: were failures really unforeseeable? Journal of Media Economics. 2004;17:261–278.

54. Picard R. The Economics and Financing of Media Companies. New York: Fordham University Press; 2002.

55. Ross, A., 2011. Investors look beyond BSkyB. Financial Times, 16 July, p. 8.

56. Sabbagh, D., 2010. Why News Corp’s buyout of BSkyB is much more than a business deal. The Guardian (Media Supplement), 20 September, p. 3.

57. Sabbagh, D., 2011. Murdoch cancels Davos visit to lead negotiations with Hunt. The Guardian, 26 January, p. 10.

58. Sánchez-Tabernero A. Issues in media globalisation. In: Albarran A, Chan-Olmsted S, Wirth M, eds. Handbook of Media Management and Economics. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006;463–491.

59. Sánchez-Tabernero A, Carvajal M. Media concentrations in the European market, new trends and challenges. Media Markets Monograph Navarra: University of Navarra; 2002.

60. Smale, W., 2010. Rupert Murdoch’s growing multi-media empire. BBC News, 15 June. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10317856>.

61. Sweney, M., 2010. Local media ownership rules to go by November. Guardian.co.uk, p. 15. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2010/jul/15/local-media-ownership-rules>.

62. Terazono, E., 2006. Convergence requires the complete vision. Financial Times, 16 February, p. 21.

63. Valcke P, Picard R, Sükösd M, et al. The European Media Pluralism Monitor: bridging law, economics and media studies as a first step towards risk-based regulation in media markets. Journal of Media Law. 2010;2:85–113.

64. Van Kranenburg H, Hogenbirk A. Issues in market structure. In: Albarrran A, Chan-Olmsted S, Wirth M, eds. Handbook of Media Management and Economics. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006;325–344.

65. Vukanovic Z. Global paradigm shift: strategic management of new and digital media in new and digital economics. International Journal on Media Management. 2009;11:81–90.

66. Webster J. Developments in audience measurement and research. In: Calder B, ed. Kellogg on Advertising and Media. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008;123–138.

67. Withers K. Intellectual Property and the Knowledge Economy. London: Institute for Public Policy Research; 2006.

1See Acheson and Maule (2004) and Graber (2006). See also Chapters 15 and 16, by Iapadre and Macmillan, respectively, in this volume.