The Economic and Cultural Value of Paintings: Some Empirical Evidence

David Throsby and Anita Zednik, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Abstract

A long-standing debate in the economics of art and culture is concerned with the adequacy or otherwise of the theory of value in economics to capture a full representation of the value of cultural phenomena. At a theoretical level it has been proposed that a distinct form of value is embodied in or yielded by cultural goods and services that is related to, but not synonymous with, the goods’ economic value. This form of value, termed cultural value, is congruent with the concepts of the value of art works that are discussed in aesthetics and the philosophy of art. Although the parallel existence of economic and cultural value can be proposed in theory, there is little or no empirical evidence to support a proposition that they are distinct phenomena or to explore the possible relationship between them. This chapter asks whether an economic assessment of the value of some cultural good will fully capture all relevant dimensions of the commodity’s cultural value or whether there will be some components of cultural value that remain resistant to monetary evaluation. We also ask whether it is possible to identify separate concepts of individualistic and collective value for cultural goods as expressed by an individual, where the former relates solely to the person’s own utility and the latter to some more disinterested view of value to the community or society in general. We illuminate these two areas with the aid of empirical evidence derived from a survey assessing consumer reactions to a group of paintings.

Keywords

Aesthetics; Economic value; Cultural value; Likert scales; Canonical correlation

JEL Classification Code

Z11

4.1 Introduction

In their contribution to Volume 1 of the Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, Michael Hutter and Richard Shusterman outline the historical evolution of concepts of value and valuation of art works as these issues have been discussed in aesthetic theory and in economics (Hutter and Shusterman, 2006). The former field has been concerned with the origins and logic of aesthetic judgment. It locates the source of value in subjective perceptions derived from a range of individual responses to a work of art. The criteria guiding evaluation may be expressed in terms of a set of formal rules, or simply as informal feelings or attitudes that influence the individual’s reaction to the work. Thus, at the point of making a judgment, the evaluation arrived at reflects the person’s taste, knowledge, experience, social class, and so on, as well as their interpretation of the technical characteristics of the work judged according to real or imagined principles of art criticism.1 Economic theory, on the other hand, is concerned with a different mode of evaluation, where tastes are assumed to be given and characteristics of the art work – such as size, medium, genre, and provenance if it is a painting – will only be of interest if they affect an individual’s preferences, his or her willingness to pay for the work, or the process of exchange that generates an actual market price. The sources of aesthetic judgment in this situation are of no concern – whatever they are or wherever they come from, they will ultimately be reflected in the individual’s monetary evaluation.

Hutter and Shusterman’s review illustrates some of the ways in which the concept of value has taken on different interpretations in both economics and aesthetics. In political economy, for example, theories of value existed well before Adam Smith (Sewall, 1901), but it was the Smithian distinction between value in use and value in exchange that led over subsequent years to a number of theoretical developments. Then the marginal revolution at the end of the nineteenth century effectively transformed the theory of value in economics into a theory of price. This transformation was perfected in the Arrow–Debreu model of general equilibrium in the mid-twentieth century to the point where Debreu could describe his axiomatic analysis of economic equilibrium simply as a (or perhaps the) ‘theory of value’ (Debreu, 1959). Meanwhile, in the philosophy of art, many different forms of value were seen to be contained within the vague concept of artistic value, with value perceived variously as arising from such sources as the moral, social, cognitive, experiential, formal, or historical attributes of art works, or of the individuals observing them, or of the context within which an evaluation was being made.2

The development of these parallel approaches to assessing the value of an art work has generated an idea that has surfaced in a number of different contexts, namely that the value of an art work (or of cultural phenomena more generally) can be assessed from two quite distinct standpoints – one derived from aesthetics or related areas and one from economics. At a theoretical level, scholars in several disciplines, including anthropology, art history, cultural studies, and sociology, have recognized that there are both aesthetic and commercial dimensions to the value of the items or processes that they are dealing with.3 For example, contributors to a volume edited by Hutter and Throsby (2008) have documented this duality of value for cultural phenomena as different from one another as contemporary art, sociology, anthropology, classical music, art history, movies, and ethnomusicology. In the real world of economic and cultural policy, the assertion that cultural goods and services differ from ‘ordinary’ commodities because they exhibit a distinct cultural value in addition to whatever routine economic value they possess has become a feature of contemporary cultural policy and of efforts to integrate it into economic or development policy more generally. For example, this assertion underlies arguments for local content quotas in broadcast media regulation and for the ‘cultural exception’ in trade negotiations (Acheson and Maule, 2006). It also determines the way the cultural industries are incorporated into international agreements such as the 2005 Convention for the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions,4 whose Preamble describes cultural activities, goods, and services as having ‘both an economic and a cultural nature, because they convey identities, values and meanings, and must therefore not be treated as solely having commercial value’ (UNESCO, 2005).

In the scholarly discipline of the economics of art and culture, discussion about the value of cultural goods and services has sharpened the distinction between the concepts of economic value and cultural value as descriptors of the value embodied in or yielded by such commodities. Economic value in this discourse is defined as the aggregate market and non-market valuation of a cultural good or service as measured in monetary terms by the conventional methods of economic analysis. The relevant market value can be assessed from price data or other indicators of direct user benefits, possibly supplemented by estimates of consumers’ surplus, while non-market value can be measured using revealed or stated preference methods. Cultural value, on the other hand, is generally seen in quasi-Lancastrian terms as comprising a series of definable attributes, including aesthetic, symbolic, spiritual, historical, social value, etc.5 Given its multidimensional nature and lack of a common unit of account, cultural value within this paradigm can be assessed for specific value components by applying various ranking or rating procedures to yield ordinal or cardinal scores.6

If the concepts of economic and cultural value for cultural goods are defined separately as above, it can be suggested that the total value of these commodities could be represented as some combination of these two distinct forms of value. Such a proposition moves the analysis outside the neoclassical framework, since in conventional economics, as noted earlier, all sources of cultural value for a particular good would be captured in its economic value, making the need for a separate concept of cultural value redundant.

The argument motivating this broadening of scope of the value concept for cultural commodities has turned on the adequacy of money as a value metric. Individuals, it is argued, may find it inappropriate or impossible to express their valuation of some cultural phenomena in terms of willingness to pay (e.g. they may have difficulty articulating in financial terms the value they place on their cultural identity or on their spiritual experiences). If it is true that a purely financial assessment of the value of cultural phenomena is incapable of capturing all the variables that affect choice, it will be inadequate as a basis for individual or collective decision making on resource allocation in the cultural arena. Such an outcome would have implications that ramify into a wide area of public and private action, including the functioning of art markets, trade in cultural goods and services, public support for cultural institutions, production of art, the conservation of heritage, and so on.

Let us return now to the value specifically of works of art. Leaving aside theories attributing intrinsic value to art objects (i.e. theories that assume that value exists whether or not it is actually perceived or acknowledged by anyone), we note that in all of the discourses discussed above, the individual observer is seen to be the agency whereby the value of a particular work is interpreted and realized. A question arises as to whether the value being expressed represents the value solely to the person himself or herself, or whether there is a claim to some generality or even universality in a person’s judgment, however ill-equipped the individual might be to make such an evaluation. Economic theory is reasonably clear on this point – individual utility drives demand, including in situations where some benefit accrues to others, such as public-good demand or altruism. Thus, expressions of value will ultimately reflect the worth of the object in terms of the person’s sense of their own utility. Aesthetic theory, on the other hand, may not be so insistent on such an individualistic interpretation under this rubric; the value being expressed by an observer in this context might be some sort of disembodied value, not necessarily accruing to or experienced by any individual in particular.

This discussion of the economic and cultural value of the arts raises a number of issues that warrant further theoretical and empirical investigation. In this chapter we take up two such issues. (i) Assuming valid measures of both economic and cultural value can be obtained for cultural commodities, will an economic assessment of the value of some cultural good fully capture all relevant dimensions of the commodity’s cultural value or are there some components of cultural value that remain resistant to monetary evaluation? (ii) Is it possible to identify separate concepts of individualistic and collective value for cultural goods as expressed by an individual, where the former relates solely to the person’s own utility and the latter to some more disinterested view of value to the community or society in general?7 We seek to illuminate these two areas with the aid of empirical evidence derived from a survey assessing consumer reactions to a group of paintings.

4.2 Hypotheses

The context in which we locate our investigation of the economic and cultural value of paintings supposes that there is a group of individuals who can be observed making their considered evaluations of a series of paintings which, for convenience, we assume are of sufficient artistic merit to be hanging in a public art gallery. We assume that the cultural value of a painting can be defined in terms of a number of specified dimensions or characteristics and that individuals can express the value they attribute to each of these dimensions according to a cardinal scale. In regard to the economic value of a painting, we assume that this can be specified in terms of the stock and flow characteristics of the work as an item of tangible cultural capital; the stock value is the price at which the work might be bought or sold and the flow value is a price attaching to the services yielded by the work over a given period of time. Noting that the values under consideration are those determined by individual observers of the works, we assume that the values expressed can be aggregated across individuals to yield a mean judgment for a given dimension relating to a given painting and that these can also be aggregated across paintings to yield a mean judgment on a given dimension relating to the group of works as a whole. However, we do not assume that the estimates of cultural value for the various characteristics of a given painting can be aggregated to yield a single composite cultural value for that work.

We put forward the following hypotheses:

• Hypothesis 1 (H1): After controlling for all other relevant influences, the cultural value of a work as assessed in relation to its various dimensions will only partially explain the work’s assessed economic value; in particular, some dimensions that are important as components of a painting’s cultural value will be unrelated to the work’s economic value.

• Hypothesis 2 (H2): Individuals can express the components of cultural value both in terms of the value accruing to themselves personally and also in terms of their estimation of the value accruing to others, and these two values will not necessarily be the same for any given attribute.

The first of these hypotheses is the critical one in investigating the relationship between economic value and cultural value; if upheld, it would be consistent with the proposition that a monetary assessment is not capable of providing a full account of the value of works of art.

4.3 Data and Method

Data to test the above hypotheses were derived from a recent survey carried out by the present authors. Randomly selected individuals entering a major public art gallery in Sydney were asked if they would be willing to participate in a survey gauging their opinions about six named paintings hanging in different areas of the gallery. The paintings were a mixture of figurative/non-figurative works from different periods by well-known and less-well-known artists.8 Two of the paintings were by Australian Aboriginal artists. Every person agreeing to take part was given a questionnaire, a pencil, and a map that helped them locate the six paintings. The questionnaire posed a series of questions that the respondent was required to answer while standing in front of each of the works. The questions were designed to elicit the individual’s cultural and economic evaluation of each of the works according to the methods described in the following paragraphs.

4.3.1 Cultural Value Estimation

Cultural value was assessed by disaggregating it into five components: aesthetic, social, symbolic, spiritual and educational value. As a test of H2, the symbolic and spiritual components were specified as value to the individual himself or herself, and value to others or to society in general. The respondent’s valuation against each cultural value component was measured using Likert-scale methodology to generate numerical ratings of value calibrated on a scale of 1–10 (low to high value).9 Following the standard procedures of this methodology, respondents were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement with a series of statements, each of which related to one of the dimensions of cultural value specified. Constraints on respondents’ time, their capacity to understand complex statements, and the potential for rapid onset of fatigue placed a limit on the number and detail of the statements that could be included.10 Moreover the translation of theoretical concepts of cultural value into simple statements that captured the essence of each dimension clearly and without ambiguity was a difficult task. Nevertheless a series of intensive pre-survey focus groups followed by pilot testing of the questionnaire enabled refinement of the statements to meet these challenges as effectively as possible.

The statements made about each painting are shown in Table 4.1, together with the particular dimension of cultural value that each was designed to assess. The interpretation of these statements is as follows.

• Aesthetic value is straightforward, being related to beauty, harmony, visual appeal, etc.

• Social value is linked to cultural identity and an understanding of the role of culture in society; one statement places this possible recognition in general terms and one frames it specifically in terms of Australian identity.

• Symbolic value relates to the narrative or meaning of a work or to the way in which the work is perceived to convey some wider cultural or other sorts of references; we assume these values to be summed up in the phrase ‘cultural significance’.

• Spiritual value is a difficult concept to pin down, being related to transcendental or mystical/religious sentiments generated by exposure to an art work; after testing various ways of specifying this value we found that the word ‘spiritual’ was itself the most effective means of conveying the required sense.

• Educational value can be clearly identified in terms of the work’s role in the education of children.

Table 4.1

Statements to elicit estimates of cultural value of paintings.

| Cultural Value Dimension | Statementa |

| Aesthetic | I find this painting visually beautiful |

| Social: for all | This painting helps us understand ourselves better as human beings |

| Social: for Australians | This painting helps us understand ourselves better as Australians |

| Symbolic: for self | This painting has cultural significance for me |

| Symbolic: for others | This painting could have cultural significance for other individuals or groups |

| Spiritual: for self | This painting conveys spiritual messages for me |

| Spiritual: for others | This painting could convey spiritual messages for other individuals or groups |

| Educational | This painting could be valuable in educating our children |

aRespondents were asked to indicate their rating on a scale shown as 1, 2, 3, …, 10 from left to right, with ‘Strongly disagree’ marked at the left hand end of the scale (1) and ‘Strongly agree’ at the right (10).

4.3.2 Economic Value Estimation

The assessment of economic value was split into two parts: (i) to measure the value of the flow of services yielded by each painting and (ii) to estimate the painting’s value as an item of cultural capital stock. The former was captured by supposing that the painting could be hired for private use for a given period of time and asking respondents how much they would be prepared to pay per week for such a rental opportunity. The respondent’s assessment of the stock value (i.e. their valuation of the painting as an object to buy or sell) was somewhat more difficult. It made little sense to ask people how much they would be prepared to pay from their own money to purchase the work. Instead, we converted the question into one seeking the respondent’s opinion on how much they thought the painting would be worth if bought for a public gallery. This question provides what might be thought of as a social valuation – what is the painting’s monetary value to society at large? In this respect it contrasts with the purely individual or private valuation in the rental question. The wording of the two questions relating to economic value is shown in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2

Questions to elicit estimates of economic value of paintings.

| Economic Value Dimension | Question |

| Flow valuation | What is the maximum amount per week that you would pay for renting this painting (assuming you had the money and the space to hang it and you could rent it for as short or as long a time as you liked)?a |

| Stock valuation | Suppose you are the Director of a public gallery somewhere in Australia and this painting came up for sale. What do you think would be a reasonable maximum price to pay for it?b |

aResponse indicated from 0 to $50 in steps of $5, with ‘more than $50’ (interpreted as $55 for analytical purposes) and ‘no opinion’ options included.

bOpen-ended response indicated.

4.3.3 Model

Let E1, E2 represent the two variables measuring economic value (flow and stock, respectively) and C1,…, C8 represent the eight dimensions of cultural value as listed above. Define vectors of control variables Z1, representing various characteristics of the paintings (size, style, etc.) and Z2 measuring sociodemographic characteristics of n respondents (gender, age, income, etc.).11 The basic model we propose is:

![]() (4.1)

(4.1)

where i = 1, 2; j = 1, …, 8; k = 1,…, n.

In other words we are assuming that survey respondents first make their judgments about the cultural worth or significance that they attribute to the work they are observing and then reach their economic assessment on the basis of these judgments, controlled for whatever effect the physical characteristics of the work might have on their economic valuation. The relationship in (4.1) is also controlled for any systematic influences exerted by respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics. Although there may be occasional examples of a reverse causation between economic and cultural value for some cultural goods (i.e. that people’s perception or knowledge of the price of a cultural good will have a positive influence on their assessment of its cultural significance),12 we assume for present purposes that this effect can be ignored.

4.4 Results

During the conduct of the survey, a total of 619 questionnaires were distributed over three days. Of these, 480 were completed and their data are included in the analyses below. Compared to the Australian population our sample included slightly more females than males, slightly more middle-aged people, and more people with a university degree or holding a managerial/professional occupation. In these respects the sample mirrored the typical profile of visitors to public art galleries all over the world. Respondents reported finding the survey challenging (‘It really made me think about these works’), but despite the challenge all who completed the survey were able to rate the paintings according to the specified criteria, such that a ranking of an individual’s scores across paintings for a given attribute could be taken to yield a valid expression of that individual’s preference ordering between paintings judged according to that attribute.

4.4.1 Estimates of Cultural Value for Self and Others

Respondents’ valuations for the various dimensions of cultural value are shown in the lower section of Table 4.3. Looking at the mean values for all paintings, we note that the symbolic and educational values of the works were the most prominent amongst the attributes in respondents’ estimations but that the ordering of the mean values across the attributes differed for different works.

The results in Table 4.3 for symbolic and spiritual value – the two value dimensions split into value for self and others – enable an ad hoc test of H2. An individual might say in regard to one of these attributes: ‘I do not value that attribute highly for myself, but I recognize its importance to others’; such a person would be expected to award a higher rating to ‘value to others’ than to ‘value to self’ for that attribute. On the other hand, an individual in these circumstances might say: ‘I value this attribute highly for myself but I do not expect others will share my valuation’, in which case the value ratings would be reversed. Thus, the differences between the values for self and for others could lie in either direction, if in fact such differences are actually indicated by respondents’ answers.

Indeed, there is no obvious prior to suggest the direction of any difference between valuations for self and others, except perhaps in the case of non-Aboriginal respondents’ perception of Aboriginal works that contain imagery and other content of significance to Indigenous people, but whose meaning may be obscure or inaccessible to non-Indigenous people; here it would be expected that ratings for others would exceed ratings for self, at least in respect of dimensions relating to cultural significance. Inspection of the results in Table 4.3 for the two Aboriginal works, Paintings 3 and 4, shows in the case of the symbolic and spiritual values of the works that the mean values ‘for others’ are significantly greater than ‘for self’, in accordance with this expectation. We also find differences in the same direction for the other paintings in respect of these two dimensions, although in most cases not by such a wide margin.

It can be concluded that this limited evidence is consistent with a proposition that individuals are capable of expressing a ‘disinterested’ evaluation of the cultural value of an artwork that they recognize as accruing to others, separately from the value that they assess as interpreted for themselves personally.

4.4.2 Estimates of Economic Value

The top section of Table 4.3 shows the mean rental or flow valuations for the six paintings, and the mean price estimates or stock valuations, as expressed by respondents to the survey. The variation in willingness to pay for private consumption varies across paintings, with the lowest offer being for the abstract impressionist work (Painting 2) and the highest for a visually pleasing nineteenth-century painting by a famous Australian artist depicting a Sydney street scene (Painting 6). The mean rental amount across all six paintings was just over $23, the median was $20, and the maximum was $55 per week.

In regard to the estimated stock values, respondents were initially told the current market price for each painting13 and asked whether they thought this was (much) too high, (much) too low, or about right. This then enabled them to locate their own estimate of the value relative to the market price. It is true that this procedure introduces an anchoring or starting-point bias into the results (Beggs and Graddy, 2009), but there was little alternative; prior testing revealed that the great majority of respondents felt incapable of making a sensible estimate of price if they were not provided with some point of reference. The differences between the individuals’ and the market’s estimates of the price of paintings shown in Table 4.3 indicate both positive and negative differentials, suggesting that people are not necessarily persuaded that the market valuation is correct, but are willing to make up their own minds.

Summary statistics for the economic and cultural values included in the model are shown in Table 4.4.

4.4.3 Relationship between Economic and Cultural Value

4.4.3.1 Overall Relationship

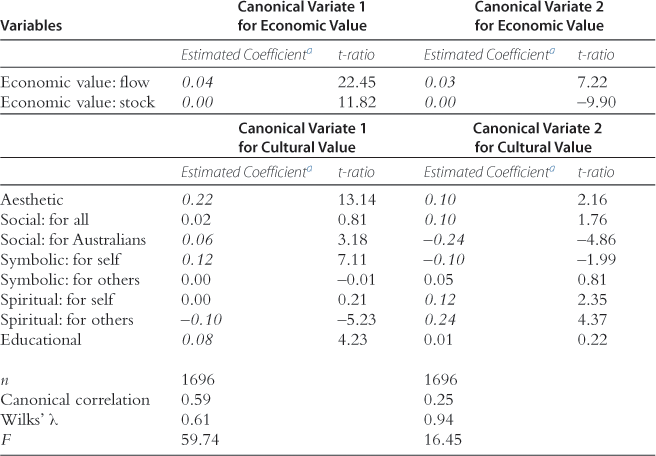

We turn now to estimating the relationship shown in Eq. (4.1) above. Since we have more than one variable on both the left- and the right-hand sides of (4.1), a useful first step is to apply a multivariate technique to estimating the overall relationship between the variables. An appropriate method is canonical correlation, which measures this relationship by finding the linear combination of the (dependent) variables that has maximum correlation with a linear combination of the other set.14

For our model, define the first canonical variates U1 and V1 as linear combinations of the E and C variables, respectively, i.e.:

![]() (4.2)

(4.2)

Canonical correlation chooses α1,i and β1,j to maximize the correlation between U1 and V1. It then proceeds to estimate the relationship between the second canonical variates, U2 and V2; these are linear combinations of Ei and Cj, respectively, that are uncorrelated with U1 and V1, and that maximize the correlation between U2 and V2. Results are shown in Table 4.5.

It is apparent that the two concepts of value (i.e. economic and cultural) are strongly but by no means perfectly related – the ‘best’ linear combination of economic values is correlated with the ‘best’ linear combination of cultural values with a canonical correlation coefficient of 0.59. The level of this coefficient falls away sharply for the second canonical variates (0.25); we note nevertheless that the second canonical variates are also significant in describing the relationship between economic and cultural value. The estimates of α1,i and β1,j indicate that the variables contributing most to the ‘best’ linear combinations are the Flow economic value on the left-hand side, and Aesthetic value and Symbolic: for self value amongst the cultural values on the right-hand side. However, caution is necessary in interpreting these coefficients as they are subject to considerable variability between samples and cannot be relied upon to measure individual influences. For this purpose it is more appropriate to estimate the relationship in (4.1) for E1 and E2 separately.

4.4.3.2 Determinants and Non-Determinants of Economic Value

To test H1, the principal proposition under examination in this study, we can regress each measure of economic value on the various dimensions of cultural value, and then look at the size and significance of individual coefficients. These results will show which items of cultural value are important in influencing economic value and which are not, and the findings can be compared with the data showing the relative importance of each cultural value dimension in forming respondents’ cultural value judgments.

The results of ordinary least-squares (OLS) estimation15 of the economic value determination model are shown in Table 4.6. We consider first the flow or rental estimates in Table 4.6. As foreshadowed above, the size and significance of the coefficients on cultural value dimensions as seen in the first column of Table 4.6 can be compared with the data in the lower section of Table 4.3. From the latter table we observe that the highest rating for cultural value among its various dimensions is for Symbolic: for others value, yet this element of cultural value has no significant effect on individuals’ rental valuations. This suggests that respondents on average have a strong sense of the narrative value or meaning conveyed by the paintings – an important indicator of cultural significance – but that they see this value as independent of their estimation of the works’ value in monetary terms. A similar conclusion can be drawn in respect of the estimates for Spiritual: for others value, which is the third most important dimension of cultural value according to Table 4.3, yet is non-significant in affecting rental value.

Nevertheless, there are some elements of cultural value which do have a positive effect on the rental value of works. Not surprisingly Aesthetic value has a strong and significant influence on the amount individuals are willing to pay to hire a painting for their own consumption, even though Aesthetic value ranks only fourth in the assessments of cultural value dimensions. Other elements of cultural value that have a significant effect on this interpretation of economic value are Symbolic: for self value and Educational value. Amongst the personal characteristics of respondents that affect their willingness to pay, we note that females, being presumably more sensitive to their domestic surroundings, will pay more to rent a painting to decorate their walls than will males; perhaps surprisingly, however, better educated people will pay less. Given the Australian content of four of the six paintings in the group, local residents show stronger willingness to pay than foreigners. Paintings by well-known artists are favored for rental, but not Aboriginal works.

Turning to factors affecting respondents’ estimates of the price or stock value of paintings, we find that the influences in this case are somewhat different. The works’ technical characteristics and authorship have strong effects in one direction or the other, with four of the five variables included having significant coefficients; as might be expected, the most substantial effect on estimates of the price of the paintings is exerted by the artist’s reputation – an observation consistent with what is known about reputational influences in the art market generally. The coefficients on the cultural value dimensions are more variable and difficult to interpret with any confidence, although the prominent influence of aesthetic value is once again clear.

Overall these results are consistent with the proposition expressed in H1, namely that there exists a relationship between the cultural and the economic value of works of art, but that this relationship is by no means a perfect one. There are some dimensions to cultural value that are important in forming individuals’ judgments as to the artistic or cultural significance of paintings but these dimensions do not influence the economic value that the individuals place on the works. In other words, in attributing value to works of art there are grounds for considering cultural value as a distinct form of value whose possible importance for decision making is not fully captured by a financial assessment.

4.5 Conclusion

In this chapter we have discussed the valuation of art works from several disciplinary standpoints, referring to the proposition that a certain duality of value exists that can be loosely characterized as aesthetic versus commercial. We have examined this concept specifically with regard to the efforts within the economics of art and culture to arrive at a sensible accommodation of non-financial values attributable to cultural goods and services. To account fully for such values in an economic assessment, researchers in economics have had to step outside the neoclassical framework that implicitly or explicitly assumes that all values can ultimately be rendered in monetary terms.

The empirical aim of this chapter has been to test a fundamental aspect of the theory of the value of cultural commodities, namely that their value can be expressed as a combination of two separate components – their economic value and their cultural value – and that the cultural value component, while related to economic value, is not subsumed by it. We have examined this proposition using data from a survey involving randomly selected individuals viewing paintings in an art gallery. We found some support for the proposition that a distinct concept of cultural value for works of art can be identified alongside the value likely to be yielded by the application of the assessment methods of economics.16 Moreover, while individuals’ cultural valuations of the works under study provided some explanation of their economic assessments of the works’ value, this explanation was incomplete, with some important dimensions of cultural value having no influence on the economic valuations. Specifically, after controlling for features of the six paintings that lie outside of the realm of cultural value, such as size of the painting or respondents’ gender, we found that some aspects of cultural value, including aesthetic and educational values, contributed significantly to explaining the economic value of paintings, whereas other aspects of cultural value that were important to respondents did not.

We also investigated the possibility that individuals could express some cultural values in terms that went beyond their own personal utility and attributed what they saw as possible value to others. Our data are consistent with the proposition that individuals are capable of articulating a distinction between what might be called an individual-based and a society-based cultural valuation. This separation can be investigated further with reference to the results in Table 4.6 if our earlier observation is recalled that the flow valuation in this study can be interpreted as an individual-related value, whereas the stock valuation is one from the viewpoint of society as a whole. It can be seen that neither of the society-based cultural value dimensions is significant in explaining the rental value in Table 4.6, whereas both society-based values have a significant (though opposite) effect on the stock-value estimates.

In this chapter we have analyzed the value of artworks along a space that spans two aspects of value – economic versus cultural value and individual-based versus society-based value. It would seem that further systematic research along these two dimensions would be useful in gaining a more thorough understanding of the relationship between the value concepts involved. There is considerable scope for more intensive work on the valuation specifically of artworks such as paintings or other collectibles, which have several advantages for this sort of investigation: their flow and stock values are readily separable, their market price can usually be easily identified, and recognizable dimensions of their cultural value are easily understood. At a wider level the comparative nature of economic and cultural valuation warrants detailed investigation in other art forms and cultural arenas. Methods of economic valuation for cultural goods and services are relatively well advanced, but a concomitant to further research in this area will be the development of more objective and rigorous methods for cultural value assessment.

Acknowledgments

This chapter is based on research carried out under a Discovery Project Grant from the Australian Research Council. We acknowledge with gratitude the cooperation of the Art Gallery of New South Wales in the conduct of the survey. Thanks are also due to Victor Ginsburgh for helpful comments on a draft of this chapter.

Appendix 1: Details of Paintings

Painting 1

Sidney Nolan (1917–1992), The Camp (1946); synthetic polymer paint on hardboard, approximately 90 × 120 cm. An iconic painting depicting an episode from the Ned Kelly story – a story that has become mythologized in Australian historical narrative.

Painting 2

Ian Fairweather (1891–1974), Triple Portrait (1970–1971); synthetic polymer paint on paperboard; approximately 106 × 75 cm. Despite its title this is an entirely abstract work by a painter who is not particularly well known, but is highly regarded in contemporary art circles.

Painting 3

Freda Warlapinni (c. 1928–2004), Pwoja-Pukumani body paint design (2002); natural pigments on linen canvas, approximately 137 × 84 cm. A non-figurative work showing the horizontal/vertical iconography of the Tiwi people of northern Australia, the area where this painter lived and worked.

Painting 4

Mawalan Marika (1908–1965), Djan’kawu creation story 2 (1959); natural pigments on bark, approximately 190 × 64 cm. An historic work by an important Aboriginal artist with complex patterns and compositional elements including some minor representations of animals (lizards, etc.), characteristic of the Yolngu art of north-eastern Arnhem Land in northern Australia.

Painting 5

Niccolo Cecconi (1835–1902[?]) A Pompeian Bath (c. 1890); oil on canvas, approximately 105 × 155 cm. A romantic nineteenth century hyper-realistic narrative painting showing female figures grouped around the edge of a luxurious Roman bath.

Painting 6

Arthur Streeton (1867–1943), The railway station, Redfern (1893); oil on canvas, approximately 40 × 61 cm. A street scene on a rainy day in an inner-city suburb of Sydney; the artist is well known and this image is likely to be familiar to many local viewers.

Appendix 2: Variables in the Model

Economic value

Flow valuation ($ per week)

Stock valuation (thousand $)

Cultural value

Aesthetic

Social: for all

Social: for Australians

Symbolic: for self

Symbolic: for others

Spiritual: for self

Spiritual: for others

Educational

The above variables measured on a scale of 1 (lowest value) to 10 (highest value).

Painting characteristics

Size (thousand cm2)

Age (years × 10–1)

Artist’s reputation (dummy: well-known = 1, 0 otherwise)

Respondent characteristics

Male (male = 1)

Age (years)

Education 1 (dummy: bachelor’s degree = 1, 0 otherwise)

Education 2 (dummy: postgraduate degree = 1, 0 otherwise)

Income 1 (dummy: annual income $50–100K = 1, 0 otherwise)

Income 2 (dummy: annual income above $100K = 1, 0 otherwise)

Australian resident (dummy: Australian resident = 1, 0 otherwise)

References

1. Acheson K, Maule C. Culture in international trade. In: Amsterdam: North-Holland; 2006;1142–1182. Ginsburgh V, Throsby D, eds. Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. vol. 1.

2. Afifi A, May S, Clark VA. Practical Multivariate Analysis. fifth ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012.

3. Beggs A, Graddy K. Anchoring effects: evidence from art auctions. American Economic Review. 2009;99:1027–1039.

4. Davino C, Fabbris L, eds. Survey Data Collection and Integration. Berlin: Springer; 2013.

5. Debreu G. Theory of Value: An Axiomatic Analysis of Economic Equilibrium. New York: Wiley; 1959.

6. Ginsburgh V, Weyers S. Quantitative approaches to valuation in the arts, with an application to movies. In: Hutter M, Throsby D, eds. Beyond Price: Value in Culture, Economics, and the Arts. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008;179–199.

7. Ginsburgh V, Weyers S. On the contemporaneousness of Roger de Piles’ Balance des Peintres. In: Amariglio J, Childers JW, Cullenburg SE, eds. Sublime Economy: On the Intersection of Art and Economics. London: Routledge; 2009;112–123.

8. Hutter M, Shusterman R. Value and the valuation of art in economic and aesthetic theory. In: Amsterdam: North-Holland; 2006;169–208. Ginsburgh V, Throsby D, eds. Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. vol. 1.

9. Hutter M, Throsby D, eds. Beyond Price: Value in Culture, Economics, and the Arts. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

10. Leibenstein H. Bandwagon, snob, and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers’ demand. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1950;64:183–207.

11. Throsby D. Economics and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

12. Throsby D. Assessment of value in heritage regulation. In: Rizzo I, Mignosa A, eds. Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2013;456–469.

13. Sewall H. The Theory of Value before Adam Smith. New York: A.M. Kelley; 1901.

14. UNESCO, 2005. Convention on the Promotion and Protection of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. UNESCO, Paris.

1For further discussion of the viewer’s contribution to aesthetic experience, see Chapter 3 by Locher in this volume.

2For a summary of these various interpretations of value in aesthetics, see Hutter and Shusterman (2006, pp. 197–199).

3Note that English suggests that prizes and awards in the arts might be seen as representing the interface between aesthetic and commercial values; see Chapter 6 in this volume.

4This Convention is discussed in more detail by Iapadre and Macmillan in Chapters 15 and 16, respectively, in this volume.

5These dimensions of cultural value are discussed more fully in Throsby (2001). The deconstruction of aesthetic value into various components has a long provenance in the history of art dating at least from Aristotle and including the well-known attribute scales of the seventeenth-century French art theorist Roger de Piles; see Ginsburgh and Weyers (2008, 2009), who analyze relationships between interpretations of economic and cultural value derived from de Piles’s data.

6For a discussion of these measurement issues in the context of heritage valuation, see Throsby (2013).

7Various aspects of cultural value, including aesthetic, symbolic, and social value, and the relationship between individual and collective value, are discussed in relation to music in Chapter 5 by Levinson in this volume.

8Details of the six paintings are given in Appendix 1.

9For details of this methodology, see, for example, contributions to Davino and Fabbris (2013).

10These limitations also meant that it was not possible to follow the desirable practice of including more than one statement relating to each attribute.

11Details of the measurement of all variables used in estimation of the model are given in Appendix 2.

12Such as suggested by Veblen; for an account of this and other of Veblen’s ideas about valuation, see Leibenstein (1950).

13As recorded in the updated register of valuations of items in the gallery’s collection.

14For an outline of this methodology, see, for example, Afifi et al. (2012, chapter 10).

15In addition to OLS we also ran Tobit estimations in case the procedure for assessing respondents’ flow value had led to truncation of this variable at the maximum specified in the question ($55). However, there was little difference between the Tobit and OLS estimates of the model.

16It might be noted that our economic assessment is limited to investigating the use value of art. Cultural goods are also understood to generate non-use values measurable, as noted earlier, by stated preference or other methods; we have not investigated non-use values in this study.