Strategic Interactions Between Modern Law and Custom

Jean-Philippe Platteaua and Zaki Wahhajb, aUniversity of Namur, Belgium; University of Oxford, UK, bUniversity of Kent, UK

Abstract

The question of the role of statutory law in social environments permeated by custom and traditional norms is particularly important when the state law aims to correct social inequalities embedded in the custom. The conventional view is that modern law often fails to take root in custom-driven poor societies, especially when the formal law conflicts with the custom. Based on a simple, static analytical model, we argue that from the low activity of modern courts we cannot infer that the statutory law is ineffectual. Indeed, there may be an effective indirect impact exerted through a ‘magnet’ effect of the formal law on the informal rulings of customary authorities. We highlight various factors impinging on this effect and illustrate their operation with a number of examples drawn from the existing literature, as well as from the authors’ own field experience. Another striking result is that pro-poor radicalism may defeat its own purpose: under certain conditions, a moderate law better serves the interests of the poor than a radical law. The same conclusion can actually be reached with the help of a more complex model in which the size of the community subject to customary mediation is itself endogenous, and the benefits and costs of remaining within the customary jurisdiction relative to those of going to the formal court depend themselves on community size. The purpose of the chapter is therefore to open to the instruments of micro-economic analysis a new field: interactions between modern statutory law and custom in the context of developing countries subject to strong and sometimes inegalitarian social norms. It will be argued that the economist’s tools can shed useful light on certain empirical facts and observations of legal anthropologists and other social scientists.

Keywords

Custom; Social norms; Human rights; Statutory law

JEL Classification Codes

A14; C71; C72; C78; Z1

22.1 Introduction

Social norms have been increasingly recognized by economists as necessary to sustain a market order. By facilitating the convergence of beliefs and actions of the agents, they help to solve many coordination problems and to sustain market governance mechanisms, whether in the framework of long-standing networks of personalized relationships or in more anonymous set-ups (Platteau, 2000; Aoki, 2001; Fafchamps, 2004; Greif, 2006). Social norms are not necessarily benevolent, however. Some of them, embedded in erstwhile customs, are clearly oppressive in the sense that they prevent significant sections of the population from emancipating themselves and realizing their capabilities in the sense indicated by Sen (1992, 1999). Two examples of such norms illustrate what these harmful effects can be.

The first example is the norm of footbinding. The underlying practice has been described by Mackie (1996, p. 999):

Beginning at about age six to eight, the female child’s four smaller toes were bent under the foot, the sole was forced to the heel, and then the foot was wrapped in a tight bandage day and night in order to mold a bowed and pointed four-inch-long appendage. Footbinding was extremely painful in the first 6 to 10 years of formative treatment. Complications included ulceration, paralysis, gangrene, and mortification of the lower limbs; perhaps 10% of girls did not survive the treatment.

A Chinese practice, footbinding appeared in the Sung dynasty (960–1279) and ‘spread by imitation until people were ashamed not to practice it’; it became ‘clearly the normal practice by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644)’ (Mackie, 1996, p. 1001).1 Originated under conditions of polygyny as a means of enforcing the imperial male’s exclusive sexual access to his female consorts (who are thereby prevented from running away), footbinding lasted for no less than 1000 years. It suddenly ended during the years culminating in the 1911–1912 revolution, which coincided with the intense education campaign led by the natural-foot movement identified with liberal modernizers and women’s rights advocates, and with the decline of female household labor (involved in tasks that could be done with bound feet) in the face of increasing competition from the cheaper products of modern industry (Mackie, 1996, pp. 1013–1014).

The second example is female genital cutting or mutilation (FGM). It comprises ‘all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons’ (WHO, 2011). These include clitoridectomy, excision, and infibulation. It probably originated on the western coast of the Red Sea in pre-Islamic times and is almost certainly associated with slavery: slave traders infibulated young Sudanic female captives who were shipped down Nile Valley routes or through the Red Sea to Egyptian or Arabian markets (Mackie, 1996, pp. 1008–1009).2 Like footbinding, the practice was justified on the grounds that it protects female purity, seclusion, chastity, and fidelity, and hence family honor.3 Today, it is prevalent in 28 countries and is most widely spread in Africa, stretching from Mauritania to Ghana and Cameroon, and extending to the East-African coast (Gruenbaum, 2001; Wagner, 2011). Twelve countries have prevalence rates over 50% and in five of them as many as 90% of adult women have been cut (98% in Somalia). In Africa alone, an estimated 92 million girls aged 10 and above have been circumcised (WHO, 2011). Unfortunately, there is no indication that this harmful practice is receding despite its disastrous consequences for the health of women (enhanced risks of vaginal discharge and genital ulcers/sores) and for their psychological well-being.

Oppressive or inequitable norms may be of two types:

i. Social conventions whereby people act in a coordinated manner, yet share a similar distaste for the ensuing outcome. We label them consensual oppressive norms. Think of the informal norm prohibiting the remarriage of widows in India, dowry payments (India), or funeral rituals (China) that cause parents to have a preference for sons and result in the scourge of ‘missing women’, or honor crimes and revenge killings in tribal societies.

ii. Rules prescribing a behavior about which different groups of the population have antagonistic preferences: they involve conflicts of interests and we therefore call them conflicting oppressive norms. Examples are norms of purity in the Hindu caste system, kidnap marriages,4 or exclusive inheritance practices that bar daughters from inheriting from their parents in patriarchal societies.

To decide whether an oppressive norm belongs to the first or second category is not always easy because a norm may have been preferred by a particular group in the past but is now unanimously disliked. That applies to norms regarding child marriage, polygamy, footbinding and FGM, for example.

Related to the above distinction is the question of whether harmful norms and practices may have been, or may be, socially efficient5: while FGM, footbinding, the norms of purity in the Hindu caste system, or men’s right to easily repudiate their wives in Muslim countries are a clear reflection of an asymmetrical power structure that conceivably causes a social loss (see Appendix for an illustration), polygamy (born in a context of land abundance and labor scarcity when social structures were rather horizontal), revenge killings (when violence was a way to signal a tribe’s strength and desire to be respected in the absence of a monopoly of power), the wearing of the veil (initially intended as a social marker distinguishing between respectable and slave women), and pro-son inheritance practices (when marriages were arranged by families and not easily broken so that women had a guaranteed access to their husband’s land) may have been an efficient response to particular circumstances in the past.6

The key point for our purpose is that oppressive norms or customs clearly disadvantage or victimize at least a fraction of the population and, therefore, an enlightened government may be eager to suppress them by using the main instrument at its disposal – legal enactment.7 The readiness to do so is enhanced if, in addition to being inequitable, such norms and customs have also become socially inefficient.

It is often argued, however, that many of such laws tend to remain ‘dead letters’. The idea is that one should not expect an oppressive, deep-rooted custom to disappear or recede as a result of a legal change when such change is not accompanied by a sociopolitical transformation susceptible of modifying the prevailing power balance. The fact of the matter is that formal institutions and rules aimed at protecting the interests of marginal groups or eradicating harmful practices are undermined in practice by informal, local rule-based systems and the social norms that underpin them. When statutory laws ignore or try to stamp out conflicting customary practices, they fail to have an impact and remain a ‘dead letter’ (Chirayath et al., 2005, p. 5; Sage and Woolcock, 2007; Ako and Akweongo, 2009). They are actually unenforceable since enforcing them would involve arresting and imprisoning entire communities (Coyne and Mathers, 2010).

The resistance of informal or customary systems is especially likely to be manifested when the modern law attempts to deal with matters of personal status such as marriage, divorce, succession, and land tenure. For instance, in countries where the law forbids marriage (brideprice or dowry) payments (e.g. Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Central African Republic, India, among others) or FGM (Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Egypt), people often continue to follow the custom as though this law did not exist (Ntampaka, 2004, pp. 128–130; Nambo, 2005).8 The same applies to statutory provisions contained in new Family Codes that aim at ensuring women’s right to inherit from their parents and at protecting them against the practices of early marriage, abrupt and uncompensated repudiation, male tutorship, or levirate (Cooper, 1997, pp. 17–18; Elosegui, 1999; Ellis and ter Haar, 2004; Coulibaly, 2005; Boshab, 2007; Field and Ambrus, 2008).9

Laws that have been enacted in sub-Saharan Africa with the aim of preventing excessive fragmentation of rural landholdings, whether through inheritance or through land sale transactions, have never been enforced. This is because of the people’s widespread belief that, since the law runs counter to deeply entrenched customary principles (such as the rights of all male children to receive an equal portion of the family land), it is unlikely to be followed by others or backed by appropriate sanctions (André and Platteau, 1998). In Peru, a new water law (‘ley del agua’) that prescribes fee payments by users of irrigation water was met with the fierce opposition of members of Andean communities. According to a deep-rooted custom, indeed, it is a communal good that should remain free.

The above evidence amply attests that the enactment of a statutory law may not be sufficient to bring about the desired change when existing practices are supported by, or enshrined in, deep-rooted norms. At the same time, we must avoid jumping to the conclusion that the law is a useless instrument in all circumstances. The present contribution precisely aims at shedding light on the conditions under which the law may have an impact on (harmful) informal norms, thus explicitly allowing for the possibility of zero effect of the law. We focus mainly on conflicting oppressive norms since they are obviously the most difficult to change. We also tackle the tricky question as to how radical the law needs to be in order to have maximum effectiveness, thereby revisiting the old debate between revolutionary and moderate approaches to change.

We first look at the potentially relevant theoretical literature drawn from economics (i) in order to determine when and how a formal law can influence the custom (see Section 22.2), and (ii) to clarify the debate between reformism and radicalism (Section 22.3). Section 22.4 then elaborates on two insightful experiences. The first one illustrates the new economic theory of strategic interactions between the modern law and the custom, while the second one points to the need for complementary actions when the modern law fails to influence the custom. The first case study deals with a norm of inheritance, which unambiguously falls into the category of conflicting norms. As for the second case study, it addresses the issue of FGM – a norm that is usually seen as belonging to the other category (consensual oppressive norms). In fact, this characterization is debatable: insofar as some groups of people, such as female practitioners and certain religious authorities, defend the practice strenuously, FGM rather appears as a conflicting norm. Section 22.5 concludes.

22.2 The Effect of Legal Reform on Customary Practices: An Overview of Economic Theories

In recent years, formal institutions, social norms, and, more broadly, culture have been represented in a number of different ways using game-theoretic concepts. In this section, we consider the extent to which such theories can provide insights about the influence of the formal law on customary practices. In the review that follows, attention will be directed to six distinct theoretical approaches to the problem at hand. These approaches suggest different ways in which oppressive or inequitable (conflicting) customs can be influenced by formal rulings.

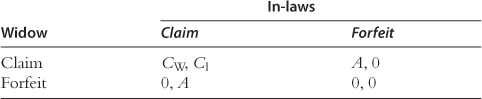

To facilitate comparison and provide coherence to the discussion, we focus on a specific case; namely, the right of widows to inherit the property of a deceased husband. The models we consider will be sufficiently abstract and simple, and can easily be adapted to other scenarios where customary practices and the formal law conflict with one another. Agarwal (1994), on the one hand, and Haugerud (1993, pp. 162–182), André and Platteau (1998), and Platteau (2005, pp. 254–255), on the other hand, have highlighted the general problem of weak property rights of women in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, respectively. They have paid special attention to the predicament of widows since the relatives of a deceased man often take hold of his property by force even when the formal law recognizes his widow’s right of inheritance. If the practice is very common, and the in-laws are expected to fight for the property, then a widow may not lay a claim to her deceased husband’s property at all to avoid the financial and psychological cost of conflict, but return to her paternal home for economic and social support. On the other hand, it seems reasonable to suppose that if the widow had made a claim to the property and fought for her rights, then the cost to the in-laws of taking hold of the property would be substantially higher. Using this reasoning, we can represent the choices available to the widow and the in-laws using a simple 2 × 2 game (Table 22.1). The row-player represents the widow and the column-player represents the in-laws. The value of the deceased husband’s property equals A and if there is only one claimant to the property then this equals his (her) payoff. If either party forfeits the property, then they receive a payoff of zero. If both parties claim the property, a conflict arises. The resulting payoffs are intended to summarize the uncertainty of the outcome as well as the psychological and financial costs of being involved in such a conflict. We allow the payoffs from conflict to the two players (CW for the widow and CI for the in-laws) to be different to indicate that the conflict may be asymmetric with the probability of winning or the psychological cost to be borne being much higher for one party than the other.

22.2.1 The Formal Law as a Focal Point

This is a version of the rival-claimants game that Basu (1983, 1997) has used to argue that market interactions cannot be sustained unless their participants observe a specific type of social norm. Myerson (2004) adapts the game to highlight how a range of institutions, including property rights law, a legislative assembly, a national constitution, as well as traditional leaders, can improve efficiency of interactions within a social group by reducing the incidence of conflict.

If CW, CI > 0, it is the best-response for each party to forfeit the property when the other party lays claim to it and vice versa. Therefore, the game has two Nash equilibria: (Claim, Forfeit) and (Forfeit, Claim). The actual outcome can then depend on a focal point, in the sense defined by Schelling (1960), which dictates the expectations of both the widow and the in-laws regarding the behavior of the other. The history of previous instances of widowhood or the customary practice seems, in such situations, to be a plausible candidate for the focal point. We would thus reason that widows forfeit their husband’s property and the husband’s relatives take hold of it because doing so is the best-response for each given their expectation about what the other party will do and, furthermore, that these expectations are shaped by customary practice (e.g. Akerlof, 1984; Kuran, 1988, 1995; Greif, 2006, pp. 3–53; Basu, 1997, pp. 312–314, 2000; Bicchieri, 1997, pp. 25–28). The outcome can then be described as an institution in the sense of Aoki (2001, p. 10): ‘a self-sustaining system of shared beliefs about a salient way in which the game is repeatedly played’. It also evokes the idea of a (stable) social convention found in Young (1996) and Bicchieri (2006, pp. 34–42).10

In this scenario, the formal law can strengthen the property rights of widows if it succeeds in altering the focal point (i.e. if people mutually believe in the representation that the law stands for). To put it more precisely, there needs to be a decree that, in the absence of a will, widows should hereafter inherit the property of their deceased husbands and in-laws have no claim over it, and this decree must successfully change the expectations about the actions of each party. Only when this second condition is satisfied may we obtain an equilibrium where the widow indeed inherits the property of her deceased husband. However, the key question (i.e. under what conditions the formal law can cause a change in the focal point) is outside the remit of the theory.

The same framework highlights an alternative mechanism through which the formal law can influence the custom. If a legal reform succeeds in changing the value of the parameter CW such that we obtain CW > 0, then the modified game will have a unique Nash equilibrium in which the widow will ‘Claim’ the property and the in-laws will ‘Forfeit’. Thus, the legal reform will succeed in strengthening the property rights of widows. In concrete terms, if a legal reform is to influence the customary practice, it must improve the widow’s prospects in a conflict sufficiently such that she would choose to fight for her deceased husband’s property even if she expected that her in-laws would do the same. This can happen only if, in the event of a conflict, the formal law is able to provide a ruling in favor of the widow as well as enforce its ruling, at least with some positive probability.

22.2.2 The Formal Law as a Threat Point

In the previous section, we explored the possibility that the formal law influences the custom by affecting people’s expectations about how others will behave when faced with a strategic choice. An equally legitimate approach, with considerable grounding in empirical studies, is the idea that the custom corresponds to an outcome of a bargaining game, for which the formal law serves as the threat point. Specifically, in the case of the widow and her in-laws, it is reasonable to suppose that the division of the deceased man’s property is the subject of informal negotiations and either party can initiate formal legal proceedings if they choose to.

Banerjee et al. (2002) propose this mechanism as a possible way through which an agricultural reform law passed in West Bengal, India in 1977 strengthened the property rights of tenant farmers and led to an evolution of the terms of sharecropping contracts in their favor. In a different context, Chiappori et al. (2002) show that the supply of labor by different household members is influenced, among other factors, by the extent to which divorce laws favor the husband or the wife; thus, the household division of labor, which is, arguably, shaped by both custom and bargaining among household members, is also influenced by formal laws dealing with an entirely different aspect of marriage.

Dixit (2007) highlights how bargaining theory can serve as a tractable framework for analyzing informal negotiations between trading partners in the shadow of the formal law. The situation under study in this chapter is broadly similar to the aforementioned and, if a particular customary practice can be represented using a framework of bargaining, then results from bargaining theory can be applied readily to obtain insights about the influence of the formal law.

Let us denote by α the share of the deceased man’s property which accrues to the widow after bargaining between the two parties. Let VW (.) and VI (.) be the indirect utility functions of the widow and the in-laws from a given level of wealth. Suppose that the formal law prescribes that the widow should inherit a share f of the deceased man’s property, with the remainder going to the in-laws, and that the total cost of accessing the formal court, including legal fees and the delay in obtaining a decision, can be represented by a disutility of C for both parties. Then, the Nash bargaining solution to the problem can be written as:

![]() (22.1)

(22.1)

where A, as before, indicates the size of the deceased man’s property. Although both parties are likely to have other forms of wealth, we omit these factors in Eq. (22.1) as they do not affect the analysis that follows. Figure. 22.1 shows the Utility Possibility Frontier of the widow and her in-laws from different ways in which the property of the deceased man may be divided. The point x depicts the threat point that, we have argued, can correspond to the outcome of formal legal proceedings. If the cost of accessing the formal court and the subsequent legal battle is significant for both parties, utility levels corresponding to the formal verdict would lie within the Utility Possibility Frontier. Point y depicts the Nash bargaining solution corresponding to threat point x.

A change in the formal law that gives the widow a greater share of her deceased husband’s property would improve her utility from the threat point and lower that of her in-laws. In a large number of cases, this would also improve her welfare from bargaining at her in-laws’ expense, but such an outcome is not inevitable. In particular, following the reasoning in Lundberg and Pollak (1993), if both the widow and the in-laws derive utility from, and provide funds for, certain expenditures (e.g. expenditures on the deceased man’s children) the change in the formal law may leave the outcome of bargaining unchanged. The reason is that, in a non-cooperative equilibrium, the party that loses out from the change in the law would simply cut back on ‘public-good’ expenditures, and the other party would make up for it. A decline in the cost of accessing the formal legal system would improve both parties’ utility from the threat point and therefore its effect on the actual division of the property decided upon is ambiguous. However, Ngo and Wahhaj (2012) show, for constant elasticity of substitution utility functions, that such a shift in the threat point would favor the party that is initially in a stronger bargaining position. Thus, if the widow is initially in a weaker bargaining position, making the formal courts more efficient can, in fact, weaken her property rights further.

We provide a simple illustration of this result. Let us assume, for ease of exposition, that A = 1 and VW(.) = VI(.) = V(.), with V′ > 0 and V′′ > 0. It is possible to show that the first-order condition to (22.1) is both necessary and sufficient for determining the value of α*.11 Using the first-order condition to (22.1), we obtain:

![]() (22.2)

(22.2)

Differentiating throughout (22.2) with respect to C, we can show that:

![]() (22.3)

(22.3)

where G(α,f,C) is negative in the solution to the bargaining problem.12 Therefore, for α* > 1/2 (so that V′(α*) > V′(1 – α*)), we have that ∂α*/∂C > 0. This means that if the widow were initially getting less than half the share of her husband’s property, then a decrease in the cost of accessing the formal court (a decrease in C) would, in fact, cause her share to decline.

The intuition behind this result is as follows. As the cost of accessing the formal court decreases, so does the surplus from bargaining. Consequently, the difference in their utility levels from the threat point becomes more important relative to the surplus, and hence more important for their respective bargaining powers. Thus, we obtain the paradoxical result that if the cost of accessing the formal courts are lowered for both parties, such a change will favor the party that is initially in a stronger bargaining position.

22.2.3 The Customary Authority as a Strategic Player

In Sections 22.2.1 and 22.2.2, we considered models where the customary practice was represented by the strategic choices made, or an agreement reached, by widows and in-laws. An alternative approach would be to represent the custom as being set by an individual, or group of individuals, in order to maximize his/her/their own objective function. In practice, the customary authority may consist of a council or assembly composed of influential members of the community (e.g. elders, lineage heads), such as the shalish in Bangladesh or the bagarusi (courts of elders) among the Haya of Tanzania (Chirayath et al., 2005; Davis, 2009).

The customary authority is likely to have his own preference about what the customary practice ought to be, but may be willing to adapt his position for strategic reasons that we describe below.13 Individuals whose rights are not well-protected by the customary practice may consider appealing to a formal court of law if the latter promises better protection of their rights. An appeal, however, would ostensibly weaken the authority and prestige of the customary authority. To avoid such an outcome, there are two ways in which use of the formal court by community members may be discouraged: (i) by the threat of social exclusion and (ii) by adapting the custom so that those who are favored within the formal legal system are content with the customary ruling regarding any conflict. Social exclusion can be costly for the community, as it will effectively lose one of its members (at least temporarily); however, it would have to be exercised to maintain a credible threat for the future.

Aldashev et al. (2012b) develop a simple model along these lines to highlight how the customary practice may be influenced by the cost of accessing formal courts, the uncertainty in the outcome of formal legal proceedings, as well as the formal law itself. We adapt the basic framework introduced in Section 22.2.2 to illustrate the main features of this model.

Suppose the division of property between the widows and the in-laws is decided by a customary authority with the following utility function:

![]() (22.4)

(22.4)

where αC denotes his preferred custom, A is the size of the property, EW (EI) is a variable that takes a value of 1 if the widow (in-law) has been excluded from the community and 0 otherwise, and SW (SI) is the social cost of excluding the widow (in-laws). We modify the utility functions of the widow and in-laws as:

![]() (22.5)

(22.5)

where FW (FI) is a variable that takes a value of 1 if the widow (in-law) has appealed to the formal court and 0 otherwise, CW (CI) is the cost of accessing the formal court for the widow (in-laws), and P represents the penalty of social exclusion for the person being excluded. In both Eqs. (22.4) and (22.5), α represents the final decision regarding the division of the deceased husband’s property, whether this decision is made by the customary authority or the formal court.

The sequence of events within the game is as follows.

i. The customary authority provides a judgment regarding the dispute between the widow and the in-laws, which we represent by αD.

ii. The widow and the in-laws decide simultaneously whether they will appeal the decision of the customary authority in a formal court of law.14

iii. If an appeal has been made by either party (FW = 1 or FI = 1), a formal judge provides a ruling regarding the division of property according to the prescriptions of the formal law, f.

iv. If FW = 1 or FI = 1, the property is divided according to the prescriptions of the formal court. However, the party who initially brought the dispute to the formal court is subject to a punishment by the community, represented by P.

There are two decisions that, arguably, should depend on incentives faced by individuals, but are triggered automatically in the model. The first is the social exclusion imposed on individuals who appeal to the formal court. Although social exclusion is costly for the community, Aldashev et al. (2012b, p. 8) argue that community members would be willing to carry out such punishment ‘to maintain the prestige of the customary authority, on which they depend not only for the resolution of conflicts but also for a variety of other functions, such as representation of the community in negotiations with outside agents’. The second decision indicated above is the ruling provided by the formal court. After presenting the main results within this framework, we shall consider the implications of modeling the formal judge as a strategic player.

We define two threshold values for the custom, αI and αW, at which the in-laws and the widow, respectively, are indifferent between accepting the verdict of the customary authority and making an appeal to the formal court. For ease of notation, we assume hereafter that A = 1. Then, using (22.5), we obtain:

![]() (22.6)

(22.6)

Neither party will appeal to the formal court if the local authority declares a custom in the interval [αW, αI] containing f.15 Therefore, if αC lies in this interval, it is optimal for the local authority to declare a division of property corresponding to his preferred custom (i.e. αD = αC) and this will be accepted by both parties.

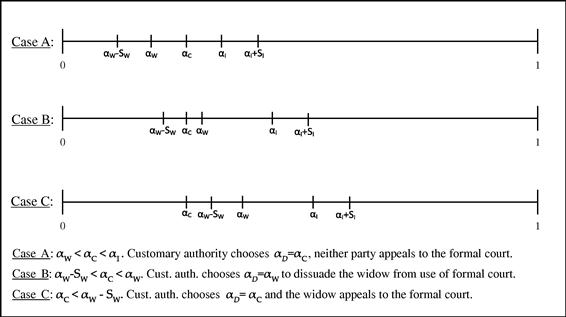

If αW > αC, the widow will not accept the local authority’s preferred custom (i.e. she will appeal to the formal court if he chooses αD = αC). In this situation, the local authority has two alternatives: he can choose αD = αW to ensure that the widow does not appeal his verdict or αD = αC and have his authority challenged. From (22.4), we see that the local authority will deviate from his preferred custom and choose αD = αW if αW > αC + SW and αD = αC otherwise. Similarly, if αI < αC, the in-laws will not accept the local authority’s preferred custom. In this situation, the local authority will choose αD = αI if αI > αC – SI and αD = αC otherwise. Figure 22.2 summarizes the three possible cases when the formal law is more favorable to the widow than the customary authority’s preferred custom (f > αC). For f > αC, we obtain three additional cases corresponding to Cases A, B and C in Fig. 22.2.

Figure 22.2 Three possible cases when the formal law is more favorable to the widow than the customary authority’s preferred custom.

We are now in a position to analyze the impact of a change in the formal law regarding the division of a deceased man’s property on the custom. Suppose that, initially, the formal law corresponds to the custom (i.e. f = αC). Then αC is in the interval [αW, αI]. In this case, it is evident that the legal reform that leads to a small increase in f will have no impact on the custom. As f increases, the interval [αW, αI] shifts to the right till we obtain αW = αC (i.e. f = αC + CW + P). At this point, further increases in f will cause the custom to evolve in the direction of the formal law. This ‘magnetic effect’ of the formal law will persist till we obtain αW = αC + SW (i.e. f = αC + CW + P + SW). Any further increase in f will cause the customary authority to revert back to his preferred custom. A similar reasoning applies if we begin to decrease f starting from f = αC.

Thus, within this model, the impact of the formal law on the custom is non-monotonic. Neither mild reforms (f close to αC) nor radical reforms (f much larger or smaller than αC) can induce the customary authority to deviate from his preferred custom. By contrast, moderate reforms will ‘pull’ the custom in the direction of the formal law. Specifically, the formal law has an impact on the custom in the intervals [αC + CW + P, αC + CW + P + SW] and [αC − CI − P − SI, αC − CI − P].

In some respects, the conclusions we reach using the model presented in this section are similar to what we obtain using the bargaining model. In the latter case, the formal law can influence the custom by affecting the threat point of the bargaining game. In the former case, as we have just seen, the formal law can change the costs and benefits of maintaining a particular custom for the local elite. However, we obtain the additional insight that, if the customary authority finds it very costly to deviate from its preferred custom, radical reforms may well be counter-productive.

Thus far, we have assumed that the judge in a formal court of law would provide a ruling in the dispute in accordance with the letter of the law. However, in reality, the formal judge may have strategic reasons to deviate from the prescribed law just as the customary authority can deviate from the existing custom. One possible reason why the formal judge may not follow the letter of the law is that he has his own views about how the property of the deceased man should be divided between his widow and his relatives.

Aldashev et al. (2012b) assume that the formal judge receives utility from following the letter of the law (called the ‘benefit of law abidingness’) and a disutility for deviating from his own preferred judgment. Then, for a given law, some judges will follow the letter of the law, while others may ignore it and provide judgments according to their own sense of justice or attachment to tradition.

A change in f may cause some formal judges to accept it; however, others, with a different view of the matter, may come to rebel against it. However, as Aldashev et al. (2012b) show within this framework, when the formal law is reformed to make it more favorable to one party over another, the one that is favored in the letter of the law may actually do worse in terms of actual outcomes in the formal court. We briefly explain the intuition behind the result.

Let us assume that a legal reform favoring the widow is carried out. The formal judges will respond to this change in three ways. Among those who were previously following the letter of the law, some will continue to do so. Others, however, may find the new law too radical and begin to provide rulings according to their own sense of fairness. A third group, which found the old law too biased against widows and therefore provided them a greater share of the property than that prescribed by the law, would find the new law more acceptable: however, in following the prescriptions of the new law, they would be providing judgments less favorable to widows than before.

Thus, the first group of judges mentioned above becomes more ‘progressive’ in response to the legal reform, but the second and third groups become more ‘conservative’. Therefore, it is conceivable that, on average, widows receive verdicts less favorable than before when they take their disputes to the formal court. Such a result is more likely to be obtained when the formal law is considered too radical by the majority of judges in the formal court. In this instance, a radical legal reform may again prove to be counter-productive.

22.2.4 The Influence of the Formal Law When the Custom is Dynamic

In the models considered above, the custom has no scope for evolving except through exogenous events that alter the focal point or the relative payoffs from conflict. It is important to recognize, however, that the custom can also change as a result of internal forces, specifically as a result of actions by individuals who live within it. How would the presence of a formal legal system affect the internal dynamics of a custom? Bowles (2004) has shown how institutional change driven by accidents, idiosyncratic behavior, or collective action can be modeled using stochastic evolutionary game theory, pioneered by Foster and Young (1990). We will show, using such a framework, how legal reforms can successfully accelerate changes in the custom, even if there is no visible impact on customary practices in the immediate aftermath of the reform.

We continue to make use of the normal-form game introduced in Table 22.1 and Section 22.1 to analyze the rights of a widow in the property of her deceased husband. However, we extend and modify the framework as follows.

We assume that in each period, there is a new group of widows and in-laws, arranged in pairs, who face the situation depicted in Table 22.1. A fraction 1 – ω of widows and a fraction 1 – ω of in-laws are assigned strategies according to the distribution of strategies used in the preceding period. We can think of these fractions as simply copying the strategies they have seen or heard about being used by older relatives or neighbors. The remaining fraction ω of widows and in-laws opt for the strategy that yields a higher expected payoff given their expectations about the strategy to be used by the opposing party. These expectations are based on the distribution of strategies used in the preceding period. The players are thus myopic but, as Bowles (2004) argues, ‘this updating process … may realistically reflect individuals’ cognitive capacities’ (p. 408). However, with some small probability ɛ, the players (in the fraction ω) choose a non-best response strategy for reasons not explicitly modeled. In the context of a widow’s property rights, this may include whim, error in judgment, or temporary shocks that affect one’s opportunity costs.

If CW, CI > 0 and ɛ is small, as Bowles (2004) shows, the system will be ‘drawn’ to either of the Nash equilibria – (Claim, Forfeit) or (Forfeit, Claim) – of the original game. That is, in the long run, most in-laws will claim the property and most widows will forfeit or vice versa. The system thus exhibits persistence and history-dependence in the sense that the customary practice in the past is a strong predictor of customary practice in the future. However, given the small probability that the widows and in-laws actually opt for suboptimal strategies, it is possible for one equilibrium to be ‘dislodged’ in favor of another.

If we are initially in the state where all in-laws ‘Claim’ and all widows ‘Forfeit’ then, using Table 22.1, widows will continue to find the strategy ‘Forfeit’ optimal unless and until a fraction of in-laws greater than –CW/(A – CW) (recall that CW is negative) choose to ‘Forfeit’ for idiosyncratic (exogenous) reasons. Hereafter, more and more of widows will choose to ‘Claim’, making it less and less attractive for in-laws to do so; this gives rise to the possibility that eventually most widows will ‘Claim’ and most in-laws will ‘Forfeit’. The same reasoning applies if a fraction of widows A/(A – CI) chooses to ‘Claim’ for idiosyncratic reasons. Therefore, the fractions –CW/(A – CW) and A/(A – CI) are, as argued by Bowles (2004), measures of the persistence of the custom (Forfeit, Claim). The greater are these thresholds, the less likely is it that the custom will evolve as a result of internal dynamics to a situation where widows have stronger property rights.

What role can the formal law play in this framework? We reasoned in the previous section that if the formal law has some influence over the outcome of a conflict (i.e. at least some widows seek recourse in the formal court when both parties ‘Claim’ the property and the formal court has some ability to enforce its ruling), a legal reform can, arguably, be represented by a change in the parameters CW and CI. If the initial customary practice is that widows ‘Forfeit’ and in-laws ‘Claim’, a legal reform that strengthens the position of widows (an increase in the value of CW and/or a decrease in the value of CI) will weaken its persistence, as represented by the fractions –CW/(A – CW) and A/(A – CI). We argued in the previous section that the legal reform can cause a switch in the equilibrium if it can make it worthwhile for widows to ‘Claim’ their deceased husbands’ property even when they expect their in-laws to do the same (i.e. if it succeeds in making CW positive). In a framework where we allow the custom to evolve according to its own internal dynamics, we see that even a small increase in CW or a small decrease in CI can, by weakening the persistence of the current institution, increase the probability that there is, eventually, a change in the custom.

22.2.5 Subjective Game Models

Aoki (2001) proposes a game-theoretic framework for studying institutional change in which, it is assumed, each agent has a ‘limited, subjective perception of the structure of game that he or she plays’. Such a notion may be pertinent for an analysis of the impact of formal law on customary practices as individuals in traditional societies may be unaware of the strategic choices that are available to them through the formal legal system, especially if there have been recent changes to the formal law or if the formal institution itself is a recent phenomenon. For example, following the introduction of a new Family Code in Morocco in 2003, covering all matters relating to marriage, parentage, children’s rights, and inheritance, a 2008 survey in three regions of the country found that only between 24% and 38% of respondents were able to explain one or more of its clauses (Chaara, 2011).

In this section, we consider potential insights about the role of formal law in shaping customary practices as they can be gleaned from the framework proposed by Aoki. In modeling institutions as specific equilibria of a game, Aoki (2001) identifies four key factors in determining what type of institution will arise:

| A | The set of all technologically feasible actions. |

| CO | The relationships between technologically feasible action profiles and technologically feasible consequences. |

| E | Beliefs held by each agent about the actions that others in the game will choose. |

| S | The best strategic choice for each agent, given their beliefs E. |

However, Aoki argues that ‘individual agents cannot have a complete knowledge of the technologically determined rules of the game, nor can they make perfect inferences about other agents’ strategic choices’. In particular, Aoki argues that an agent’s choice of action may be drawn, not from A, but from an ‘activated subset of strategic choices’ A*, representing the strategic alternatives that he or she is aware of at a point in time. An institution, Σ*, is represented by the set of beliefs from E that are common to all agents. Given Σ*, each agent has a ‘subjective consequence function’ CO* that he or she uses to infer the consequences and payoffs from his or her choice of strategy. Finally, given A*, Σ*, and CO*, each agent has a perceived ‘best-response choice rule’ S* that may differ from S.

Within this framework, institutional change may occur through Aoki (2007, pp. 19–20):

… changes in the activated sets of individual choices due to the accumulation and development of skills, learning, innovation-induced new action possibilities, and so on. Or, they may be changes in technological and environmental conditions that result in different physical consequences for the same action choices. They may be new laws or fiats which are enacted as consequences of the game in the political domain, but appear as exogenous changes in the parameters of consequence functions in other domains.

In the context of a widow’s right of inheritance in her deceased husband’s property, there may be a number of possible actions available to her when the property is being contested, including appeal to the customary authorities in her husband’s community, request for support in the dispute from her own paternal relatives, use of the formal legal system, or some combination of these. However, if the widow has not previously had experience of the formal law, which is a plausible assumption in societies where the division of a deceased man’s property is normally determined by custom, she may not consciously consider making use of the formal legal system. In this case, her ‘activated subset of strategic choices’ need not correspond to her strategy set.

If the widow is ignorant of the option of going to the formal court, it may be possible to sustain certain strategy profiles as equilibrium outcomes even though they do not qualify as Nash equilibria of the objective game. To illustrate this point, we shall consider a modified version of the rival-claimants game as follows.

In Table 22.2, we assume that CW, CI > 0; α + β = f + g = 1; α, β, f, g > 0 and 0 > B > A. Compared to the game depicted in Table 22.1, we have added two new strategies for each player, ‘Share’ and ‘Formal Court’. In specifying the payoffs, we have assumed that if both parties ‘Claim’, or if one party proposes to ‘Share’ while the other party chooses to ‘Claim’ the entire property, a conflict ensues that results in the payoffs CW and CI. The other strategy pairs consisting of combinations of ‘Claim’, ‘Share’, and ‘Forfeit’ do not lead to conflict: each party, in effect, receives what it asks for. The payoffs associated with any configuration of actions involving an appeal to the formal court by at least one player are fB and gB, because we assume that its ruling overrides any ruling made by the customary authority.

If we ignore the strategy ‘Formal Court’ for each player, the resulting game has three pure-strategy Nash equilibria: (‘Forfeit’, ‘Claim’), (‘Share’, ‘Share’), and (‘Claim’, ‘Forfeit’). If there is no functioning formal legal system, or if both players are ignorant about it, these three equilibria represent the possible customs that can arise in the community.

Following the reasoning offered by Aoki (2001), the strategy ‘Formal Court’ could become part of either player’s ‘activated subset of strategic choices’ through decentralized experiments of agents trying new strategies from the given sets of action choices. In our context, this could mean that a widow through her own initiative finds that appealing to the formal court is a viable option. Alternatively, she may become aware of the formal law because of information campaigns launched by the government or non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

If either party chooses the strategy ‘Formal Court’, it is assumed that the property will be divided according to the prescription of the formal law, which is represented by the constants f and g. However, there is some cost for accessing the formal law, captured in the assumption that B > A.

If the community is initially characterized by a custom that widows ‘Forfeit’ and in-laws ‘Claim’ the entire property, a widow should deviate to the strategy ‘Formal Court’ when she ‘discovers’ that it is a viable option, since fB > 0. We can argue that, as more and more widows become aware of this strategy, the relations of a deceased man can no longer reasonably expect that the widow will forfeit the property. The original custom will be dislodged. This reasoning can be formalized using the framework from stochastic evolutionary theory adopted by Bowles (2004) and discussed in the previous section.

What would happen in the long run after both players have become aware of the strategy ‘Formal Court’? Depending on the prescriptions of the formal law and the cost of accessing the formal court, one possibility is that the courts will be used for settling such disputes hereafter. However, if βA > gB and αA > fB, note that the strategy profile (‘Share’, ‘Share’) can also be a (evolutionarily) stable equilibrium. Thus, the formal law and increasing knowledge of the law in the society would act as a catalyst for an evolutionary process which eventually leads to a new custom. Beginning with a customary practice in which widows receive very little of their deceased husbands’ property, the following conditions are sufficient for the formal law to play such a role:

i. A widow who has knowledge of the formal law has sufficient incentive to appeal to the formal court over accepting the outcome of the existing custom;

ii. There is scope for an alternative customary practice that provides both parties greater utility than the outcome of formal legal proceedings, inclusive of legal costs, waiting period, and uncertainty inherent in the formal legal process.

The mechanism for institutional change proposed here, based on Aoki’s notion of ‘subjective game models’ is akin to the effects of the formal law on the threat point of a bargaining game, discussed in Section 22.2. However, there is an important difference. In the present instance, the evolutionary process is not sensitive to the precise content of the formal law, in the way that the threat point of a bargaining game would be. The crucial point is that, when a widow is made aware of the formal law, she should find it sufficiently attractive compared to the existing custom to appeal to the court. This will cause a breakdown of the existing custom and provide the conditions for a new, more egalitarian custom to arise.

22.2.6 The Customary Authority as a Forward-Looking Player

In the preceding sections, we have considered various models in which the custom is shaped by strategic choices made by agents involved in a dispute and by others who have the authority to act as arbitrators in such disputes. A common feature in these models is that the agents are short-lived or, more precisely, have a one-period horizon when making their strategic choices.

However, a customary authority whose prestige and wealth stems from the social and economic activity within the community should, arguably, take into consideration the impact of any decision it makes on future membership in the community. Specifically, if the customary law is unfavorable to some section of the community, it is possible that individuals would opt to leave the community even before they are involved in a dispute, to avoid being subject to the customary law at a later date. If the customary authority is forward-looking, he should take this potential outcome into consideration.

Similarly, if the customary authority expects economic opportunities outside of the community to improve in the near future, it may opt to make the custom more progressive, so as to induce individuals to remain within the community. Alternatively, he may decide that a decline in community membership is a fait accompli and, consequently, opt for a conservative custom. To the extent that the formal law affects the quality of life outside of the community, legal reforms would influence community membership in a similar manner to changes in economic opportunities. Therefore, legal reforms as well as expectations regarding future changes in the law can influence the evolutionary path of the custom. However, the preceding discussion suggests that this influence can be either positive or negative, depending on the agents’ preferences, community membership, and outside opportunities.

To determine the conditions under which progressive legal reforms would induce the custom to evolve in the same direction, Aldashev et al. (2012a) develop a dynamic model of the custom and formal law where the customary authority behaves as a forward-looking agent. In the following sections, we provide a brief presentation of the model and discuss lessons we can learn from the exercise.

22.2.6.1 Description of the Formal Model

Imagine a population consisting of two groups of players, A and B, and an additional player M who represents the customary authority. The game consists of an infinite number of periods and, in any period, an individual must either ‘belong to the community’ or be ‘outside of the community’. The steps of the game within each period are as follows.

1. A stochastic variable, representing the ‘current state of the economy’, is realized and its value is made known to all players.

2. The customary authority declares a ‘custom’, conceived as a continuous variable varying between 0 and 1.

3. Each player who belongs to the community decides whether he or she wishes to remain in the community during the period in question or leave the community.

4. Each player discovers whether he or she has become ‘embroiled in a dispute’ during the current period, with a player of the other group. Whether this happens or not depends on a realization of a binary stochastic variable.

5. For each dispute, the customary authority gives a ‘verdict’ which corresponds to the custom declared in Step 2 above; all other disputes are settled in ‘the formal court’.

6. For those disputes settled by the customary authority, the disputants must decide whether to ‘accept’ the verdict or ‘challenge’ it by making an appeal to ‘the formal court’. In the case of appeal, the formal court gives a verdict (also a value comprised between 0 and 1) in line with the prescriptions of ‘the formal law’.

7. If there is an appeal, the customary authority imposes a punishment on the community member who has challenged his verdict.

At the beginning of the next period, all existing community members remain within the community and those who left the community in the last period now find themselves outside it. A player who has exited the community has no possibility of re-entering it.

At the end of each period, the customary authority receives a ‘payoff’, which is increasing in the size of the community and decreasing in the proportion of community members who challenge his verdict. Moreover, for each dispute that he arbitrates, his payoff is decreasing in the extent that his verdict deviates from some given ‘preferred verdict’. Each community member receives a payoff that is also increasing in the size of the community and, if they have been involved in a dispute, increasing in the extent to which they are favored by the verdict (given by the customary authority if it is an intra-community dispute and there is no appeal or by the formal court otherwise). All those outside of the community (including those who have exited in the current period) receive a payoff that depends on the current state of the economy and on the value of their ‘outside opportunities’. In addition, if they have been involved in a dispute, their payoff is increasing in the extent to which they are favored by the verdict in the formal court. As for the outside opportunities, their value varies across players and is observed only by the player concerned, but it is constant over time.

22.2.6.2 An Interpretation of the Formal Model

In the context of the property rights of widows, the ‘preferred verdict’ of the customary authority reflects at the present time the community’s dominant custom regarding the division of the property of a deceased man between his marital and paternal family. In contrast to much of the Law and Economics literature (see, e.g. Dixit, 2007, pp. 10–29), it is assumed that the customary authority has the ability to impose punishments on community members who challenge his decisions. The ‘formal court’ makes use of the written law of the state and, it is assumed, people are well-informed about it and have sufficient trust in its enforceability.

Individuals who ‘belong to the community’ participate in the production of, and enjoy the fruits of, community-level public goods. They have economic and social interactions primarily with other community members, and these interactions may include informal mechanisms of social protection, assistance in house construction, religious celebrations, village meetings and feasts, social events and ceremonies on the occasion of births, marriages, funerals, circumcisions, etc. Their payoffs are assumed to be increasing in community size as the scope of such interactions and the benefits of collective action are likely to be greater when there are more people involved (e.g. informal insurance is more effectively provided when the risk-pooling group is larger).

Individuals who choose to leave the community lose these benefits. However, they are able to participate in the modern economy. The quality of their life then depends on the current state of the economy and on their personal resources, which may include their skills, assets, and social network. In the event of a dispute, an individual who has left the community may not have his case settled by the customary authority any more. The modern court is the only legal framework available for dispute settlement.

In a situation of conflict between the widow and the paternal family of the deceased man, the customary authority makes the first attempt to arbitrate their dispute. If either side is unhappy with his ruling, they may appeal the verdict in a formal court of law. If the dispute reaches the formal court, his ruling overrides that of the local authority. Unlike that of the customary authority, the behavior of the formal judge is conceptualized in the simplest possible manner: he consistently applies the statutory law and his judgment is known in advance with full certainty by the possible litigants.

22.2.6.3 Theoretical Results

We assume that the formal law is more favorable to the property rights of widows than the dominant custom. Under these conditions, female members of the community would have some incentive to exit or to appeal to the formal court if they are involved in a property dispute with their in-laws. If the current state of the economy and its future prospects are sufficiently strong (a high value in the current period and high expected value in future periods), those with the best opportunities outside the community will choose to leave. Those with weaker opportunities will generally remain in the community, but may appeal to the formal court if they have sufficient stake in a particular dispute. Otherwise, they accept the judgment of the customary authority. Thus, we obtain a situation of legal dualism, where both the formal court and the customary law are actively used by the population.

Aldashev et al. (2012a) show that, in the event of a legal reform that strengthens the property rights of widows, women belonging to the marginalized group may leave the community and, henceforth, rely on the formal courts for the settlement of their disputes. Similarly, there is likely to be greater appeal to the formal courts by female community members. However, more importantly, such a legal reform may incite the customary authority to adapt the custom. In particular, if the loss in the value of the community public good that results from exit by community members, the loss in prestige from appeal, and the psychological loss in declaring a custom that deviates from the preferred verdict of the informal judge are all greater for higher levels of exit, appeal, and deviation, respectively, the custom may move in the direction of the formal law following a legal reform.

Moreover, the custom has its own dynamic, separate from changes within the formal legal system. If the outside opportunities of community members improve over time because of expanding markets, or community membership declines over time for exogenous reasons, this will also cause the custom to evolve in the direction of the formal law.

22.2.6.4 Discussion

It is important to note, however, that there are a number of instances in which this mechanism would break down. In a traditional society in which there are few economic opportunities outside of the community and little use of the formal court system by community members (perhaps because of a credible threat of severe punishment), incremental changes in the formal law should not have an impact on the custom: in this situation, the disincentives against using the formal courts are so strong that the customary authorities have little reason to make the custom more acceptable to the marginalized section of the community.

The conditions indicated in Section 22.2.6.3 ensure, in effect, that the customary authority gives more weight to the remaining vestiges of his prestige precisely when this is eroded by a decline in community membership and challenges to his authority through appeals to the formal court. However, it may well be that the marginal loss to his prestige begins to decrease beyond a certain point. If so, further changes in the formal law, or improvements in the outside option, will cause the custom to evolve in the opposite direction (i.e. in the direction of his preferred custom). This possibility provides a cautionary tale against radical reforms that excessively erode community membership.

Along similar lines, if there is a limit in the extent to which the customary authority is willing to deviate from his preferred custom, radical reforms will only succeed in eroding membership in the traditional community without bringing about significant changes in customary practices. This can potentially have a detrimental effect on the welfare of those who have the weakest outside options, who remain within the community after the reforms have been carried out.

22.3 Radical or Moderate Legal Reforms?

In the above analysis, we came across several arguments pointing to the desirability of moderate rather than radical legal reforms. In this section, we want to present a more complete and unified approach to the question of the optimal law, as can be inferred from the recent contributions of Aldashev et al. (2012a,b) in which judges are seen as strategic actors. In Section 22.3.1, we thus rehearse what we have learned from Section 22.2 about the tradeoffs involved in the choice between radical and moderate legal reforms, and we add new arguments that highlight the issue. In Section 22.3.2, we adduce evidence of some ineffective radical laws that governments had to mitigate when their innocuousness became evident. Finally, in Section 22.3.3, we cite two examples that illustrate the effectiveness of moderate laws.

22.3.1 Theoretical Considerations

In the discussion below, we present three distinct strands of argument that can support the case of moderate legal reforms: the welfare argument, the law enforcers’ behavior argument, and the subjective argument.

22.3.1.1 The Welfare Argument

In a static framework, it has been shown by Aldashev et al. (2012b) that neither mild nor radical reforms can induce the customary authority to deviate from his preferred custom. This is in contrast to moderate reforms that will ‘pull’ the custom in the direction of the formal law. The intuition behind this result is that the informal judge may find it too costly to pronounce a verdict that departs from the custom, if the statutory law is too much at variance with it. In other words, the informal judge balances the cost and benefit of deviating from the custom. The cost is the utility loss arising from making a judgment that differs from his own preferred judgment; the benefit is the advantage, in terms of power and prestige, of keeping contenders within the realm of his jurisdiction. If the modern law is too radical, the cost becomes too large relative to the benefit and the judge chooses to stick to the custom. People belonging to disadvantaged groups are compelled to leave their village community, and forsake the benefits of the local ‘social game’, in order to secure the protection of the formal court.16

Can we make a similar argument when the approach to strategic judgments is dynamized in the way suggested in Aldashev et al. (2012a)? The answer is yes. Let us assume the existence of a social planner whose objective function consists of maximizing the aggregate welfare of all members belonging to marginal groups. A positive effect of a radical ‘progressive’ legal reform is the induced adaptation of the custom in the direction of the modern law (provided that we are in the conditions where the magnet effect operates). Such a reform also has a direct impact on the welfare of those who find themselves outside of the community and on those within the community who are embroiled in disputes severe enough to prompt them to challenge the authority of the informal judge. These two effects would suggest that the marginalized section of the population would always benefit from a legal reform that renders the formal law more favorable to them. However, this reasoning ignores the additional fact that the reform encourages exit from the community, thus lowering the value of the community public good for those who remain behind (since this value depends on the size of the community).

Whether an increased progressiveness of the statutory law will lead to improved welfare of the disadvantaged section of the population thus depends on the relative importance of three effects. Nevertheless, Aldashev et al. (2012a) establish two important facts about the social impact of a legal reform that generally hold true. The first is that the social impact of an increase in the value (degree of progressiveness) of the formal law is more likely to be positive in a more ‘modern’ economy, where ‘modern’ means that individuals have relatively strong alternative options outside of the community. In this instance, indeed, a large fraction of the population will already have exited the community and the negative impact of a ‘progressive’ legal reform on the community public good will be felt by only a small number of individuals. Furthermore, the positive impact of a higher value of the formal law will be felt by a large number of individuals who have joined the modern segment of the economy and therefore resort to the formal legal system to resolve their disputes.

The second fact is that, among the disadvantaged, a ‘progressive’ legal reform will not affect all individuals in the same way. For those who are already in the modern economy, the effect is unambiguously positive because they benefit directly from the new, more ‘progressive’ law, whereas they do not suffer from a possibly weakened community system. Those who switch to the modern economy in response to the legal reform are, in fact, exchanging the value of the community public good for their outside option. Those with the highest values of the heterogeneous component of the outside option within this group are, therefore, most likely to benefit from the switch. On the other hand, those who remain within the community benefit the least since they hold onto an option that has been rejected by the others. If the customary authority is reluctant to respond to the change in the formal law – behavior that can be determined by a sharply increasing cost of deviating from its preferred judgment or by a decreasing marginal loss to its social prestige once community size has fallen below a certain threshold – this last group of individuals may be adversely affected by the reform owing to reduced provision of the community public good that follows the others’ exit.

It follows from this discussion that, if the social planner assigns greater weight to the individuals who have the most limited options, a moderate reform may be superior to a radical reform. This is a direct implication of the fact that those individuals who have no realistic alternatives to living in the community benefit from a legal reform only to the extent that the custom evolves in the same direction as the formal law, while they suffer a loss commensurate to the decrease in the provision of the community-level public good.

22.3.1.2 The Law Enforcers’ Behavior Argument

As pointed out in Section 22.3, not only customary authorities but also modern judges are sensitive to the extent to which the statutory law departs from their preferred judgment. Too radical a law may, therefore, deter a significant proportion of the modern judges from applying it strictly, thus making the legal reform self-defeating. In the above-explained setting in which these judges receive a positive utility from applying the law (law abidingness is a concern for them), yet suffer from departing from their own preferred judgment, there exists a threshold value of the formal law above which a judge will stop passing judgments corresponding to the law and follow his own preferred judgment. There are obviously as many such thresholds as there are values of the preferred judgment among the modern judges.

The expected utility of a marginalized individual from pursuing a case in the formal court therefore depends upon the probability that he or she faces a modern judge whose preferred judgment is sufficiently ‘progressive’ to incite him to strictly enforce the law. It is evident that the more radical the legal reform the lower the fraction of law-abiding judges and the higher the probability of meeting a judge who has chosen to enforce his preferred judgment rather than the new law.

The same argument can be actually applied to modern law enforcers. Even assuming that modern judges follow the new ‘progressive’ law, there remains the question as to whether their verdicts will be duly enforced. Legal enforcers have a preference for enforcing the legal verdict, which is their formal duty, but suffer a loss of utility increasing in the distance between this verdict and their preferred outcome. If the distance becomes too large, they stop enforcing the law. Since legal enforcers are heterogeneous in their preference, a more radical law is likely to induce a fall in the proportion of them who enforce the law strictly, thus counteracting the effect of legal reform.

This is especially true if the enforcement of the formal judgment requires the effective cooperation of local customary authorities. In the case of land conflicts, for example, since land is an immobile asset that belongs to a given community space, there is a relatively high risk that the judgment of the formal court will not be properly enforced if is too different from the prevailing custom.

Such a line of reasoning has been persuasively followed by Kahan (2000) on the basis of US evidence. According to him, the resistance of law enforcers sometimes confounds the efforts of lawmakers to change social norms. For example, as legislators (in the United States) expand liability for date rape, domestic violence, sexual harassment, drugs, and drunk driving, not only do prosecutors become more likely to charge, jurors to convict, and judges to sentence severely (our second line of argument), but also the police become less likely to arrest the culprits and enforce the legal verdicts. The conspicuous resistance of these decision makers in turn reinforces the norms that lawmakers intended to change.17 With the help of a graphic argument, Kahan argues that this pathology of ‘sticky norms’ can be surmounted if lawmakers apply ‘gentle nudges’ rather than ‘hard shoves’. When the law embodies a relatively mild degree of condemnation, the desire of most decision makers to discharge their civic duties will override their reluctance to enforce a law that attacks a widespread social norm.18

There is a rather crude manner in which these refinements can be brought to bear in the static model proposed by Aldashev et al. (2012b) and presented in Section 22.2.3. The outcome of the modern law process has now become uncertain, because not only the judgments but also the way in which they will be enforced are not known by the disputants. The actually enforced verdict is therefore a stochastic variable with a finite variance and, moreover, its variance depends on the level of ‘progressiveness’ of the modern law. In terms of the model, a decrease (increase) in the variance of the formal verdict yields the same (magnet) effect as an increase (decrease) in its mean value. As a consequence, if the values of these two statistics rise together (since they are interdependent in the above-suggested manner), a more ‘progressive’ law may well turn out to be innocuous and even harmful for the marginalized groups of the population. The latter eventuality will materialize if the variance of the formal law rises proportionally more than its mean value as the latter is raised.

22.3.1.3 The Subjective Argument

We have so far assumed that members of marginal groups fully identify themselves with the statutory law and the state authority system in the following sense: they believe that a relatively ‘progressive’ law unambiguously ‘represents’ their interests. In other words, their perception of the law coincides with the intent of the lawmaker. This need not be so, however. An oft-observed characteristic of dominated people is, indeed, that they internalize the dominant values and norms shaped by the elites and legitimize the authority systems established by the latter. In the words of Rao and Walton (2004), they are subject to ‘constraining preferences’. This leads them to unknowingly adopt attitudes and defend opinions contrary to their own interests, out of what Marx has called ‘false consciousness’. The distorted perception of what constitutes their genuine interests typically results from a deep attachment to a tradition they are reluctant to call into question (the elites do not have such a problem insofar as the tradition protects their interests), especially so if the tradition is naturalized or made sacred (e.g. because it is embodied, or alleged to be embodied, in religious tenets).

A remarkable illustration of such a possibility has been provided by Ashok Rudra (1981) when he described the resistance of Bengali sharecroppers (the Bargadars) against a land reform enacted by the (communist) government to transform their precarious rights into full ownership rights. The root cause of their resistance, as he documented, was their deep-seated belief that it would be wrong and illegitimate to acquire assets that had always belonged to their benevolent masters (in a similar vein, see Scott, 1976, pp. 41–51).19 To take another example, an Indonesian Muslim woman who was the only surviving child in her family did not dare claim all the inheritance when the judge was ready to grant it to her. As a justification for her decision to let a cousin have a share of the parental wealth, she referred to a desire to act righteously, according to the Islamic customary prescription (Bowen, 2003, pp. 195–199).

Upon careful thinking, however, there are two distinct ways in which disadvantaged people may fail to fully identify with the modern law: (i) their preference over legal outcomes is shaped by the elite’s values that they have internalized through their socialization process and (ii) they have a loyalty feeling toward the customary institution, so that resorting to an alternative institution sparks a painful internal conflict in them. In the first case, the ‘magnet’ effect is obviously prevented from operating, while the mechanism at work in the second case requires that the argument running through the static model be refined. The following assumption can thus be made: whenever a ‘progressive’ shift towards a better protection of their interests occurs through a change in the custom, marginalized people fully value the move, implying that any increase in the value of the custom is fully accounted for in their utility calculus. By contrast, any such change effected through the official legal order is discounted. In other words, valuation of an increase in the value of the formal law in their utility function is imperfect or incomplete, being weighed down by a discount factor comprised between 0 and 1. As a result, the size of the ‘magnet effect’ is mitigated in proportion to the magnitude of the discount factor.

It may help to think of the discount as an internal punishment, caused by some sort of guilt, inflicted by a marginal person on himself or herself for shifting loyalty to the modern legal order. When this interpretation is adopted, the following relationship becomes more plausible: the more the statutory law differs from the custom, the more significant the loyalty shift of the community members seeking recourse to the formal court and the greater the guilt feeling or the associated utility loss experienced by them. An inverse relationship between the discount factor and the level of ‘progressiveness’ of the statutory law is thus suggested. Clearly, we may encounter situations in which the discounting of the rising value of the formal law becomes so important that the net effect becomes nil or negative. To emancipate marginalized people, a radical law would then be less effective than a more moderate one.

22.3.1.4 Summary and Remark

There are thus several strong reasons that may call for moderate rather than radical legal reforms. To sum up the analysis, moderate reforms are more likely to be effective (to promote the interests of the disadvantaged sections of the population) if:

| Mechanism (a) | Alternative options outside of the community are more scarce, the benefits from local public goods are more sensitive to community size, and the customary authority is more reluctant to respond to a change in the formal law by adjusting the custom. |

| Mechanism (b) | The proportion of modern judges, or legal enforcers, close to the threshold beyond which law abidingness becomes less important than following own preferences is larger. |

| Mechanism (c) | Marginalized people are more prone to internalize dominant values and legitimize customary authority systems. |