6

PLANNING AND CONTROL OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT EXPENSES

RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES

The terms research and development are often used imprecisely. Each may have a myriad of connotations, and even though these two words often are used together, each represents a different process with differing implications in terms of planning and control. Research as used herein relates to those activities in a business enterprise that are directed to a search for new facts, or new applications of accepted facts, or possibly new interpretations of available information, primarily as related to the physical sciences. It is the activities or functions undertaken, often in the laboratory, to discover new products or processes. Development, however, as discussed herein, denotes those activities that attempt to place on a commercial basis that knowledge gained from research. In another sense, the efforts discussed in this chapter are those that normally would be managed by the vice president or director of research and development (R&D).

Although R&D activities may be grouped in any number of ways—and proper classification is important in the planning and control function—this segregation is often used internally by those entities that do extensive work in these three areas:

- Basic or fundamental research. This may be defined as investigation for the advancement of scientific knowledge that does not have any specific commercial objective. It may or may not be, in fields of present, or of possible, interest to a company or a customer.

- Applied research. Activity in this area would relate to the practical application of new scientific knowledge to products or processes in which the company has an interest.

- Development. Functions under this classification would include those efforts or studies to get the product or process into full-scale commercial production.

For those financial executives who deal with budgeting efforts in the R&D area, and who are desirous of having the activity defined, here are separate definitions for “research” and “development.”

- Research is an organized search for new knowledge that may lead to the creation of an entirely new product, or that will lead to the development of a new process, or which will substantially improve an existing product or process.

- Development involves the systematic translation of new knowledge into the designs, tests, prototypes, and pilot production of new products or processes. It does not involve minor enhancements to existing products or processes.

IMPACT OF R&D ACTIVITIES ON CORPORATE EARNINGS

The most effective assistance of the financial discipline in respect to the planning and control of R&D expenses probably must recognize the role these expenditures can and should play in the economy as well as in a given business.

R&D in the United States is conducted by a diverse number of institutions: the federal government and other governments; industry; universities and colleges; nonprofit types of organizations; and professional firms that conduct research for others. Although the efforts of these groups have resulted in the technological superiority of the United States in the mid-twentieth century, now it has become evident that reduced expenditures at the federal level and a hostile climate for new ideas and products are threatening this position. Whether it be because of uncertain business conditions, shortsighted corporate management, lack of adequate incentive, unacceptable governmental regulation or procedures, the fact remains that such a trend may well have adverse implications for the U.S. economy.

There is evidence, in an aggregate sense, of the relationship between technical innovation and the stimulation of economic development. Within a given manufacturing company, in terms of a particular project or projects, perhaps no simple cause-and-effect relationship between R&D expenditures and net income can be found. However, statistical correlation suggests a tendency for earnings to increase, over a period of time, with an increase in research spending. Empirical data tend to show that under the private enterprise system, industrial firms grow and prosper by developing, or investing in new products or processes, or improving existing ones. It simply is not enough to do reasonably well that which is being done, for competitors will pass by such a business. Innovation or improvement and management of change are the intangible attributes that distinguish the progressive company from one on the road to decline. And the wise planning and control of research and development costs should recognize this relationship.

In a very real sense, the funds spent on R&D are quite different from many other expenses. They are an investment in the regeneration, growth, and continued existence of the business and should be evaluated, insofar as possible, as an investment.

R&D ACTIVITIES IN RELATION TO CORPORATE OBJECTIVES

From the strategic and long-range viewpoint, the important corporate activities should support the corporate goals and objectives. Certainly research and development efforts should fit this category. For example, if an entity is planning substantial growth in the compact disc field, then research and development in this area should be considered. Conversely, if strategic plans call for divestiture of a television operation, then it makes little sense to expend sizable sums on R&D in this field. Moreover, R&D input regarding acquisition targets, competitive R&D activity, or the state of the art should be helpful in strategic planning. Further, strategic planning should consider the alternative of performing research in-house or of purchasing an entity already active in the product line.

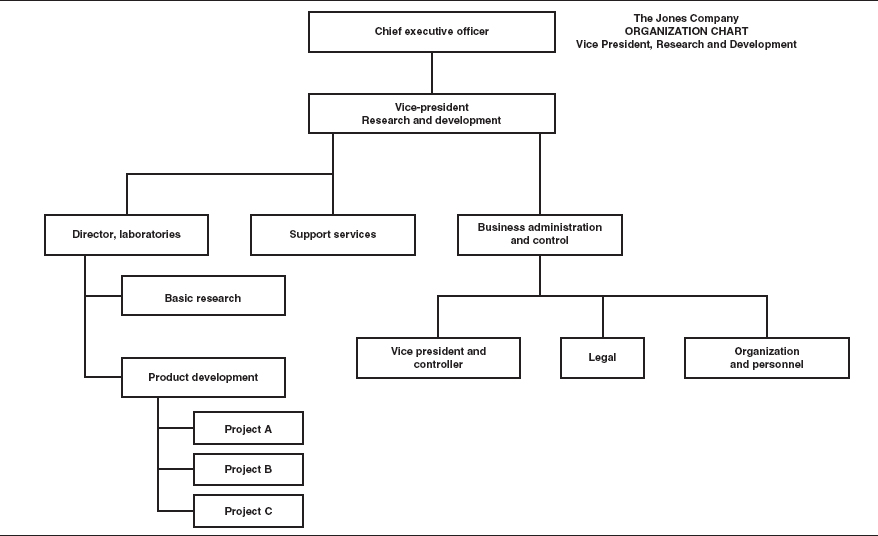

This preferred relationship between corporate objectives and the R&D plan is shown in Exhibit 6.1.

EXHIBIT 6.1 INTERRELATIONSHIP OF CORPORATE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES WITH THE R&D PLAN

INTEGRATION OF R&D WITH OTHER FUNCTIONS

Aside from understanding the proper relationship of R&D to corporate objectives, the increased competition, the often critical time factor in developing new products, and perhaps greater wisdom about the nature of R&D, is forcing a new approach in many complex R&D situations. This viewpoint has been denoted as system focus by one author.1

System focus is a philosophy which emphasizes the importance of technology integration early in the process: the mutual adaptation of new technology, product design, the manufacturing process, and user needs.

The traditional approach to R&D might be regarded as one group of executives after another adding its contribution to the developing product and then passing the task later to others down the line—in the engineering department and then in the manufacturing process and finally in marketing. This transfer of knowledge is mostly downstream. Often there is little incentive or no mechanism for sending knowledge back upstream so it can improve the technology in the next go-around. In the systems-focused organization, the goal of new product development shifts from a compartmentalized sequential approach to optimizing the whole system. Under such circumstances, the company early in the R&D process forms an integration team composed of a core group of managers, scientists, and engineers. This team investigates the impact of various technical choices on the design of the product and the manufacturing system.

The purpose of this brief section is to alert the controller to the time and cost savings inherent in this systems integration. The controller should be aware of the potential in any relevant discussions with the R&D manager, and in the formulation of the planning and control system.

ORGANIZATION FOR THE R&D FINANCIAL FUNCTIONS

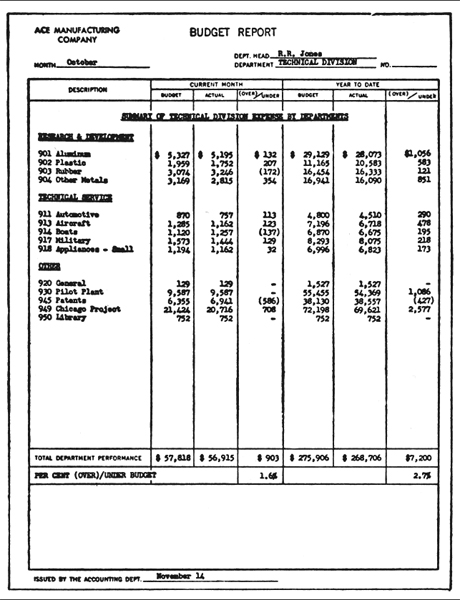

Another relevant background matter is organization. The importance of the R&D function in many companies has led to the establishment of separate organizational units, such as a division or subsidiary. Although the size of the company, scope of the research function, management philosophy, and type of research may influence the organization structure, a pattern is discernible in a review of different corporations. A self-contained unit is illustrated in Exhibit 6.2. The financial officer handling the financial aspects of R&D activity reports to the vice president of Research and Development, and provides the necessary financial analysis, accounting and reporting services, and coordination with the corporate finance group. In this instance, a “dotted line” relationship is maintained with the corporate vice president and controller.

The precise manner in which the R&D function is organized directly affects the accounting for the activity. The organization responsibilities, as defined by the functional outline or charter, provide the basis for budgeting and controlling the costs. The reporting and measurement of expenses must be guided by the organization plan; it must parallel the responsibilities of each organizational unit.

ACCOUNTING TREATMENT OF R&D IN FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

In public corporations, prior to the mid-1970s, there existed a wide difference in the balance sheet treatment of R&D costs. Given the tendency or desire in some quarters to report the highest possible earnings, as well as the high degree of uncertainty about the future economic benefits of individual R&D projects, such variations are understandable. Therefore, because of this reason, among others, and before deciding on the preferred accounting treatment of R&D costs, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in 1973 considered four alternative methods of accounting for such costs as incurred:

- Charge all costs to expense as incurred.

- Capitalize all costs as incurred.

- Capitalize costs when incurred, if specified conditions are fulfilled, and charge all other costs to expense.

- Accumulate all costs in a special category until the existence of future benefits could be determined.

The FASB concluded that all R&D costs (except those covered by contract) should be charged to expense when incurred. This treatment was to be effective for fiscal years beginning on or after January 1, 1975.

The above comments relate to R&D costs exclusive of costs of developing of software. U.S. firms may account for the costs of development of similar software products in different ways. Some costs of development of software to be sold, leased, or otherwise marketed, may be capitalized. All the costs of development of similar software created for internal use may be expensed by some firms and capitalized by others.

EXHIBIT 6.2 ORGANIZATION CHART FOR R&D ACTIVITIES

There seem to be differences of opinion between the Institute of Management Accounting (IMA) and the FASB. The results of a survey by Kirsch and Sakthivel published in January 1993, covering 139 completed questionnaires mailed to 417 of the Fortune 500 companies showed this treatment of software development costs:

Readers, if interested, can keep updated on the directives concerning accounting for software development costs.

ELEMENTS OF R&D COSTS

The Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 2 does not apply to the costs of R&D conducted for others under a contractual arrangement; this is covered by statements relating to accounting for contracts in general. It does apply to the types of costs discussed in this chapter but not incurred under a contract to outside parties.

Elements of costs identified with R&D activities would include costs of (a) materials, equipment, and special facilities, (b) personnel, (c) intangibles purchased from others, (d) contract services, and (e) indirect costs. Illustrative activities, the costs of which typically would be included in R&D and would be expensed unless conducted for others under a contractual arrangement as outlined in the FASB's Statement No. 2, include:

- Basic research related to the discovery of entirely new uses or applications

- Applied research that attempts to adapt existing discoveries to specific applications

- Testing of new concepts or adaptations of new concepts to determine operating parameters

- Design, construction, and testing of prototypes

- Design, construction, and testing tools, molds, and dies involving new technological applications

- Design, construction, and testing of pilot production facilities that are strictly for the testing of new production concepts, and not for ongoing production for sale to customers

If an activity fits into one of the above categories, then a controller should categorize any related expenses into a format that clearly breaks down expenditures for each R&D activity. Before going into the details of this breakdown, however, it is reasonable for a controller to determine the size of expected R&D expenditures. If they are comparatively small, it may be easier to roll the R&D costs into overall engineering expenses and not go to the expense of creating a separate categorization. However, if the costs are significant, costs should be grouped into the following five categories for reporting purposes, or some similar format:

- Cost of materials, equipment, and special facilities:

- Personnel:

- Department supervisory staff

- Professional staff

- Clerical and other personnel

- Intangibles purchased from others:

- Scholarly subscriptions

- Outside services such as document reproduction

- Legal fees for the filing and maintenance of patents

- Contract services:

- Any purchased service directly related to R&D, such as testing or analysis services

- Indirect costs:

- Allocated corporate or local overhead costs

Though it is important to group expenses into the proper R&D categories, it is equally important to exclude some expenses, primarily those that are no longer strictly concerned with R&D activities, but rather with commercial production. These excludable expenses are:

- Correction of production or engineering problems after a product has been released to the production department

- Ongoing efforts to improve existing product quality

- Slight product alterations

- Routine changes to molds, tools, or dies

- Any work related to full-scale commercial production facilities (as opposed to pilot plants)

ROLE OF THE FINANCIAL EXECUTIVE IN R&D

Now that much of the background information has been briefly reviewed, it might be useful to discuss some of the areas where the knowledge of the financial executive should be helpful to the research director before talking about the technical financial aspects relating to planning and control of R&D costs.

Primary responsibility for the R&D activities rests with the officer in charge of the function. However, the corporate controller and the cognizant financial executive assigned to the R&D financial duties should be knowledgeable and exercise leadership in these areas (not necessarily in the order of importance):

- Provide the necessary accounting accumulation and reporting of the costs and expenses, and assets and liabilities, of the R&D activities in an economical way, and in a manner that provides useful financial data to the R&D executives. As to expenses, this will include accumulation by type of expense, by department, and, where appropriate, by project.

- Establish and maintain proper internal controls.

- In conjunction with the headquarters controller, if applicable, and the R&D executives and managers, establish and maintain an adequate budgetary planning and control system.

- Assist in developing guidelines for the total amount to be spent on R&D activities (for the annual plan and/or strategic planning).

- Where applicable, and where quantitative analysis may be helpful, and in those instances where an economic/business viewpoint is needed, provide data to guide in establishing budgets and cost/benefit and relative risk comparisons, for R&D projects. (See the discussion of “stage-gate systems” at the end of Section Section “Effectiveness of R&D Effort”).

- Assist the R&D managers in developing the planning budgets for which each is responsible.

- Assist in preparing the annual capital budget (discussed in Chapter 11).

- Provide acceptable, practical expense control reports—either budgetary or otherwise (standards).

The remainder of this chapter relates to specific questions or tasks in the planning and control of R&D expenses.

GENERAL BUDGETARY PROCEDURE

By and large the planning and control of R&D expenses in the United States are handled through a budgetary process. The seven principal steps are:

- Determine the total amount to be spent on R&D activities for the planning period.

- Establish the individual project budgets and, where appropriate, provide related risks and costs/benefits information.

- Where applicable, as in the overall administrative function, establish the individual departmental budgets.

- After appraisal and consolidation, secure approval of the budget.

- Provide the periodic comparisons of actual versus planned expenses and the cost to completion of project budgets.

- Where needed, provide data on a standards basis—actual versus standard performance.

- Where feasible, provide measures on the effectiveness of R&D activity.

DETERMINING THE TOTAL R&D BUDGET

“How much should the company spend on R&D this year?” A great many managers ask this question. And since expenditures should give weight to the long term, the query is really a multiyear one. There are innumerable projects which innovative R&D executives can conjure up; but there are limits on what a company should spend. Many constraints must be considered, including these, in determining the total R&D budget for any given time period:

- Funds available. Most entities have financial limitations; and the funds must be within reach, not merely in the one year, but perhaps extending over several years—depending on the projects.

- Availability of manpower. In the United States, companies often are unable to secure the needed professional or technical talent for a given project.

- Competitive actions. What the competitors are doing in R&D, or not doing, usually is a factor that management must weigh. The firm should be reasonably up to date on its R&D efforts.

- Amount required to make the effort effective. If the company embarks on some specific programs, sufficient amounts must be spent. It may be foolish to spend too little; better not to attempt the project.

- The strategic plans. Future needs over the longer term to meet the strategic plan may eliminate some proposed new projects.

- General economic and company outlook. Is the company about to enter a cyclical downturn? What is the expected trend in earnings? These factors may deter new projects if the outlook seems downbeat for a time.

So, if the constraints are known, there are several guidelines in current use for determining the limits of R&D spending. Some of these measures are useful guides in determining the overall budget:

- The amount spent in the past and/or current year, perhaps adjusted by a factor for inflation as well as growth

- A percentage of planned net sales, perhaps using past experience as a guide

- An amount per employee

- A percentage of planned operating profit

- A percentage of planned net income

- A fixed amount per unit of product sold (experience) or estimated to be sold

- A share of estimated cash flow from operations

INFORMATION SOURCES ON R&D SPENDING

Aside from internal experience data developed from company records by either the R&D director or the controller, some useful information may be obtained from several external sources. Thus, trade associations may have available data on a particular industry. The Industrial Research Institute, Inc., of Washington, DC, may be another source. If a company is required to file a Form 10-K with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), this document may be available. Further, most of the national business publications such as Business Week, Fortune, or Planning Review and others periodically discuss the subject. One of the best sources is the annual “R&D Scoreboard” published in June or July of each year by Business Week. Typical material in each annual report is similar to this:

- The amount spent on company sponsored research and development as reported by each entity to the SEC on Form 10-K

- R&D expenditures for the year, by industry, as summarized in Exhibit 6.3

- Commentary on R&D's biggest U.S. spenders

- Comparison of R&D expenditures by U.S. companies versus those in other leading countries

- Significant recent developments in R&D activity

For example, in 2005 it was reported that R&D managers were learning to “make do” in a period of difficult economic times by such actions as:

- Discontinuing marginal projects

- Decentralizing R&D efforts

EXHIBIT 6.3 INDUSTRY SUMMARY—SELECTED R&D EXPENDITURE DATA FOR 2004

- Collaborating with outside experts such as consortiums, universities, other companies, or government laboratories

- Continuing internationalism in that

- (a) More research is now headquartered overseas.

- (b) Research efforts are more open to foreign participation.

- (c) New technology is being shared with developing countries.

- (d) Patent rights are being shared among certain participants.

Of course, any R&D statistical information must be carefully interpreted in that the start of major new projects or the cessation of completed ones can severely impact the quantified results of a company's effort.

ESTABLISHING THE R&D OPERATING BUDGETS

Determining the total amount to be spent on R&D for the planning year merely establishes a maximum limit on aggregate expenditures. In terms of effective planning and control, three related segments of the total operating expenses need to be determined:

- The R&D specific “projects” and their related costs

- The indirect expenses associated with the departmental R&D activities, but not part of the project direct expenses

- The departmental expenses, developed following the organization structure and “responsibility” accounting and reporting—and consisting of the project expenses for which the department manager will be held responsible, and the related (or not related) indirect expenses

Because many departmental expenses depend on which projects will be undertaken and on the estimated cost of each, the project selection and cost estimating are discussed first.

Project Selection

The selection of the particular R&D projects is primarily the responsibility of the research director, giving weight to resources available, the amount of risk found acceptable by management, the strategic plan of the company, and a proper balance between the various types of projects.

In a practical way, a judgment will be made about the relative amount of effort to be spent on various categories of projects. A typical categorization might include these, perhaps in the order of ascending risk or cost, or reducing chance of economic return:

- Sales service (projects originated by the marketing department and involving field selling practices and delivery)

- Factory service (projects requested by the manufacturing arm and relating to manufacturing processes)

- Product improvement (includes efforts to improve appearance, or quality, or usefulness of the product)

- New product research (on products about which some facts are known, but which are not yet in the product line)

- Fundamental research (research of a fundamental or basic nature) where no foreseeable commercial application is yet envisioned, and which may or may not be in fields of interest to the company

Numerous influences will enter into the decision of project selection. The research director, for example, probably would consider these factors, among others:

- Availability of qualified professional personnel. In some time spans, the necessary professional skills simply might not be available.

- Urgency of the project from a marketing or manufacturing viewpoint. Some matters may be so important, that further manufacturing or marketing of the product is not feasible until the problem is solved.

- Time required for the research. It may be that some significant problem probably can be very quickly solved, and it is considered better to resolve the matter before proceeding to other projects with a longer time span.

- Prior research already done by others. Clues or significant beginnings, either within or without the organization (universities, joint ventures, etc.), may have been found or achieved. It might be the judgment of the head of research that this past effort should be capitalized upon in the present time span.

- Prospect of economic gain as the predominant influence. Perhaps the management may believe the possible economic returns from successful research or development are so high that a given project should be undertaken without delay.

The projects to be initiated will depend on the judgment of the research director and other members of top management. However, these general observations are made, including some comments as to how a controller or financial executive may be useful:

- Because the odds of economic benefit from an investment in pure or fundamental research is quite remote, some managements may wish to place modest limits on such expenditures.

- Development projects ordinarily should be given a high priority since successful applications would tend to be more likely.

- All development projects should be “ranked” or evaluated much as are capital budget projects (see Chapter 11). The financial discipline should be helpful, applying discounted cash flow techniques, or other quantitative methods, to information provided by the research and/or marketing staff in determining:

- Total investment needed, anticipated revenue, operating expenses, and return on investment

- The relative risk

- Potential licensing income and the like

Some Quantitative Techniques in Evaluating R&D Expenditures

It is no easy task to decide on an economic basis whether R&D on a given project should be undertaken. However, there will be instances when it can be attempted.

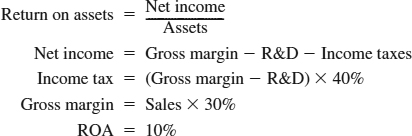

Consider, first, return on assets (ROA), sometimes described as return on investment. The cost–volume–profit relationship may add a dimension to the R&D investment decision.

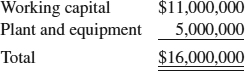

Assume these five conditions:

- Management has set a 10% return on gross assets, net after taxes, as the minimum acceptable rate.

- In one or two years after development is complete, the estimated sales of the newly developed Product T ought to attain a stable level so that aggregate sales should total $100 million.

- The typical gross margin in the business is 30%, and Product T should be no exception.

- It is expected that, when research and development is complete, the required asset investment will be:

- The expected income tax rate—federal, state, and local (netted) is 40%.

With this sales and gross margin expectation and a minimum 10% return on assets, how much can the company spend on research and development on Product T?

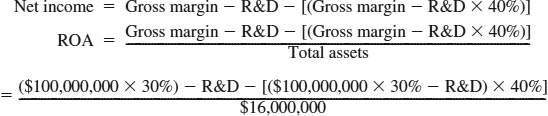

Some indication of the approximate expenditure level can be gained from this calculation:

Simplify:

Proof:

The $27,333,333 permissible R&D can be converted to a budgeted amount per annum.

Another quantitative analysis related to percent return on net sales. Some managements judge the acceptability of a product by the adequacy of its percent return on sales.

Make these three assumptions and then decide how much can be spent on R&D for the product:

- The minimum acceptable net return on product sales is 10%.

- Sales of the new product are expected to aggregate $160 million.

- The (net) income tax rate (federal and state) is 40%.

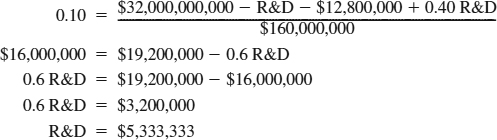

The calculation is:

![]()

wherein again,

Simplify:

Proof:

Project Risk

As previously mentioned, one factor in determining how much should be spent on a given project is the risk of that project. Although it may be difficult to calculate risk, analysis (by the controller) may provide management with some sense of the relative risk. One approach is based on the logical assumptions that (a) risk increases as a company ventures into new markets and new products, and (b) risks also increase with time from the completion of R&D until product sales commence. The concept is illustrated by the matrix in Exhibit 6.4 wherein the market objective and the time span are the factors of risk. The objective of a completed matrix is to graphically illustrate how relative risk for the planning year compares with the prior year, or how risks on R&D in one division compare with another or how one project may relate to another.

The four steps in identifying the relative risk are:

- The various proposed R&D projects for each division or marketing group or the entity as a whole are grouped by market objective (new product in new market or new product in existing market, etc.) in order of risk

- The year when the product will be initially sold is estimated

EXHIBIT 6.4 MARKET OBJECTIVE AND RELATIVE R&D RISK

- The proposed spending for each product having the same market objective is tabulated, as in Exhibit 6.5

- The results are summarized by market objective, translated to percent as in Exhibit 6.6

As illustrated in Exhibit 6.6, 30% of the expenditures in planning year 1 (20XX) are contemplated in the area of most risk—new products in new markets, as compared with only 5% in the market area deemed least risky.

The research director must judge how prudent such risk is, together with the return on assets for completing products, the total potential return, and so on.

DETAILED BUDGETING PROCEDURE

Having reviewed how the overall expenditures for R&D for a given year might be determined, some of the influences in determining what projects might be considered, and a couple of illustrations of a possible quantitative approach to judging the desirability of a given project, it might help to summarize a typical budgeting procedure and provide budgetary examples.

EXHIBIT 6.5 ILLUSTRATIVE R&D EXPENDITURES FOR A MARKET OBJECTIVE—NEW PRODUCT, CURRENT MARKET

EXHIBIT 6.6 DISTRIBUTION OF 20XX PLANNED R&D BY MARKET OBJECTIVE AND YEAR OF INITIAL IMPACT

These are the eight steps that the research director might take, with the assistance of the controller or financial executive, in some phases:

- Determine the total budget for the planning period. This may include the comparisons with some of the measures discussed earlier.

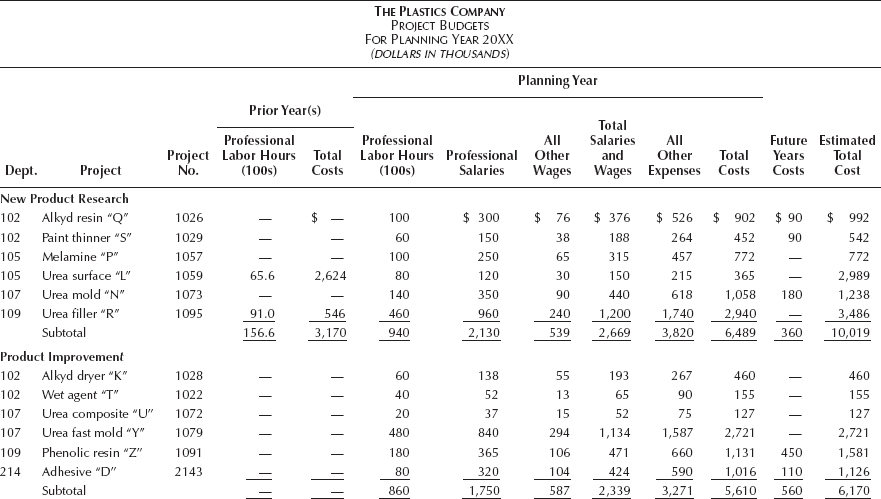

- Review the individual projects. Select those deemed the more suitable and determine the total cost in some reasonable degree of detail, as in Exhibit 6.7. Some managements may want the “other expenses” broken down into more detail.

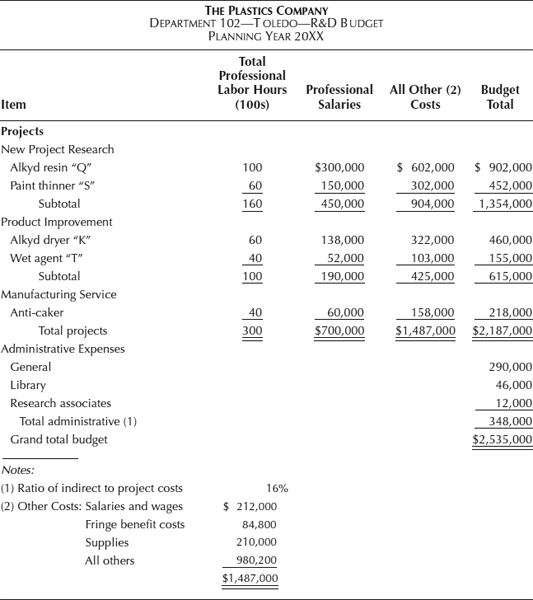

- Determine each departmental budget, based on the project costs determined in step 2, and the necessary indirect expenses, as in Exhibit 6.8. This well may involve an iterative procedure as between project costs and total departmental budgets.

- Summarize the project and departmental budgets to arrive at the proposed total R&D planning budget, as in Exhibit 6.9. Supporting this summary would be the project and departmental budgets.

- Secure necessary approval of the R&D budget (board of directors, etc.). This should be regarded as approval in principle.

- As specific projects are to begin, prepare a project budget request, with adjusted or updated data, if applicable, and secure specific budget approval.

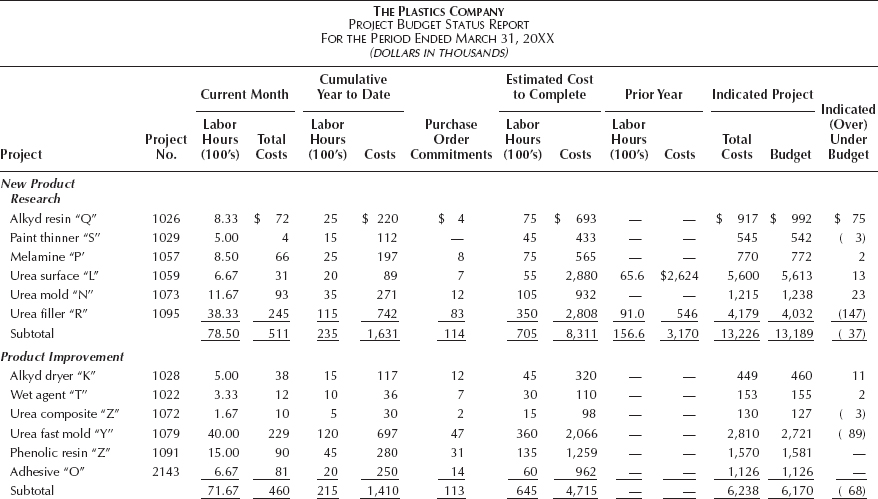

- Provide periodic control reports, comparing, as in Exhibit 6.10, actual project costs to date and cost to complete, with the budget, and comparing department actual costs with budget, as in Exhibit 6.11. In this latter case, costs are controlled by department, but not by project.

- Take any necessary corrective action.

OTHER CONTROL METHODS

As previously explained, the control phase of the budgeting process consists of comparing actual expenses and budgeted expenses for the indirect or administrative type expenses of the R&D function. Project direct expenses also could be judged in the same fashion. But it makes more sense, in this latter case, to compare estimated total expenses to complete the project—a continuous or monthly updating process—with the project budget. In this manner, if it appears that expenses are going over budget, perhaps steps can be taken to reduce some of the anticipated costs. Budgetary control probably is the most widely used method of monitoring expense trends, and correcting over-budget conditions.

EXHIBIT 6.7 SUMMARY PROJECT BUDGET

EXHIBIT 6.8 DEPARTMENT PLANNING BUDGET (DEPT. 102)

In some instances, performance standards also may be used to control costs—or to supplement budgetary control. While many phases of the R&D effort are varied and not easily subject to measurement, there are circumstances where performance standards may be useful in evaluating some of the quantitative phases of the work. Some suggested performance standards for those functions that are repetitive and perhaps voluminous include:

- Number of tests per employee, per month

- Number of formulas developed per labor week

- Cost per patent application

- Cost per operating hour (pilot plant or lab)

- Number of requisitions filled per worker, per month (lab supply room)

- Number of pages of patent applications created per man-day

- Cost per professional man-hour of total research or departmental expense

EXHIBIT 6.9 SUMMARY R&D BUDGET

EFFECTIVENESS OF R&D EFFORT

Management has often asked, and still asks, “Are the R&D expenditures worthwhile?” or “Is the company research effective?” Questions such as these do not relate to budgetary performance or performance standard results. Rather, they go to the heart of the contribution that the R&D activity, or segments of it, makes to the economic well being of the company.

Some research efforts, such as basic research, are difficult to measure because no specific or direct objective is discernible. But the reason for some projects is clearly economic, such as the discovery of a cheaper manufacturing process or a new product. For these, a kind of measurement is possible.

Some economic measures or indices that the accountant might suggest, or perhaps assist in developing, include:

- For a lower-cost manufacturing process. The savings over 1 to 5 years versus the development expense

- For a new product

- The operating profit of the product over X years as compared to the cost of development

- Rate of return on new products (DCF)

EXHIBIT 6.10 PROJECT BUDGET STATUS REPORT

- An index of market share:

- An index of share of sales from new products:

EXHIBIT 6.11 PROJECT BUDGET REPORT

- For improved products

- The operating profit from the estimated additional sales over X years versus the development cost

- Some of the ratios or measures suggested above for new products can be adapted for improved products

The effectiveness of R&D effort is principally the responsibility of the executive in charge of such activity. With the high level of foreign competition, in those instances where research and development is a critical success factor for the business, the process of benchmarking may be a means of increasing R&D productivity. Although this method has been used extensively with regard to manufacturing and marketing functions, it can be applied also to R&D activity. As discussed in Chapter 1, benchmarking is the measuring of a company's functions against those of companies considered to be the best in their class, and the initiation of actions to improve the activity under review.

In the event the controller is asked for advice regarding the application of benchmarking in R&D activities, the controller should be aware that the process has been a factor in creating (for the R&D function) the following benefits in some companies:

- Significant acceleration of the time-to-market for new products and new processes

- Assistance in transferring technology from the R&D organization to the business unit involved (an operating division or subsidiary)

- Identification and definition of the core R&D technologies needed to support the companies' planned long-term growth

- Help with the companies' efforts to tap global technical resources

- Assistance in evaluating research project selection

- Improvement in cross-functional participation in many R&D projects

Finally, in judging the effectiveness of product development, a broad business viewpoint must be considered—not merely the R&D project and/or revenue calculated for budget purposes. Management must allow for the right combination or trade-offs between cost, time, and performance requirements. This is where the financial executive, and especially the controller, can be of assistance to other management in the periodic evaluation of product development projects. Increasingly, the controller is a member of the “stage gate” group that monitors the progress of the project.

The “stage-gate” system segregates a company's new-product process into a series of development stages. These stages are partitioned by a series of “gates” which are periodic check points for such matters as cost escalation, market changes, quality control, and other risks. Each project must meet certain criteria before it can pass through the gate and down the development path. The senior managers involved, as well as the financial executive, review progress as the product approaches its market launch. Typically, in the early development phase, accurate information is lacking and financial risk is low. As the project reaches a critical point, a detailed financial analysis is desirable. The controller's department, or chief financial officer (CFO) integrates financial analysis, technical analysis, and manufacturing and marketing plans. Revealed are sales forecasts, prices, profit margins, and possibly impact of a discontinued project. The end result is said to be more efficient development operation, more new product successes, and a more flexible cost latitude (e.g., recognizing the time factor in the product success).

The stage-gate system offers a strong role for finance, but also provides sometimes beneficial cost-time trade-offs and plan changes for the product developers.

1. Marco Iansiti, “Real-World R&D: Jumping the Product Generation Gap,” Harvard Business Review, May/June 1993, pp. 138–147.