15 It's All about the Premise

Deduction

Greek philosopher Aristotle is often credited with being one of the first to document reasoning that mirrors what we call deductive reasoning today. Plato and Socrates are also in the mix of deductive reasoning creators, and there's early Egyptian and Babylonian evidence providing support for even earlier uses. The truth is, whether it was documented or not, humans have used deductive reasoning for many millennia.

Here are two simple examples, perhaps from the time of cavemen:

“When water falls from the sky, and the pond fills with water, I have water to drink. Water is now falling from the sky, and the pond is filling with water, so I will have water to drink.”

“When I touch a fire, it hurts. There is a fire over there. If I touch it, it will hurt.”

Some modern examples:

“When my global positioning system (GPS) says to drive a certain route and I drive a different route, my GPS says, ‘Recalculating.’ Oops, I just missed my turn, and I'm going to drive a different route; therefore, my GPS will say, ‘Recalculating.’”

“Every new employee must go to new employee orientation. We just hired a new employee, so he must go to new employee orientation.”

“I'm holding a cup of only red marbles. If this statement is true, any marble I take out of the cup will be red.”

The initial statement in deduction defines a general truth. Based on that truth, we can determine a specific instance is true as well. The classic example: all people (persons) are mortal (the general truth). I am a person; therefore, I am mortal (the specific).

With deductive reasoning:

- Everything is black and white. There is no gray; there is no uncertainty. It is either true or false; there is no sometimes, maybe, or depends. There is no discussion needed.

- No one will ever say, “… but …” There are no buts. If the initial statement (the premise) is true, then the conclusion will always be true. There is no argument, no debate, and no doubt.

Unfortunately, most events in our lives are not black and white. Our days are filled with maybe, depends, and sometimes. Even the expressions we use containing always and never are usually not absolute; we typically mean “almost always” and “almost never.”

Also, because there are not many absolute truths out there, we don't get to use deduction very often. You've likely heard the expression “The only things certain in life are death and taxes.” Well, we know some people don't pay taxes—so that leaves death as the only certain thing. All people die at some age; I am a person; therefore I will die someday. Maybe that's true today, but you can argue even that truth isn't absolute, as medical and technological advances progress.

Induction

Inductive reasoning also has a long history. In early years, it may have been applied like this:

“When I place the remains of an animal carcass outside my cave, it usually attracts another animal that's good to eat. So, I'm going to place an animal carcass outside my cave, and it will probably attract another animal good to eat.”

Here are more modern examples:

“The last 10 times I had a conversation with my manager, I got more work to do. I should have a conversation with my manager about this project, but that means I will probably get more work to do—so I'm not going in there!”

“In the past, our customer call center got many more calls when we raised our prices. We are raising our prices next week, so our customer call center will probably get more calls.”

“When it rains outside during the morning rush hour, it takes me longer to get to work. The weather report tonight says it's going to rain tomorrow morning during the rush hour, so it will probably take me longer to get to work.”

With inductive reasoning, the initial statement consists of a set of specific instances—many times, a set of experiences—that allows you to then generalize all future instances. The larger the set of repeating specific instances, the more confidence you'll have in it happening again.

Here's an example: A customer calls and says, “I think there is something wrong with your product. I took it out of the box and it was cracked.” Do you go running to manufacturing, screaming that all of your products are defective? Of course not. However, what if you received 100 customer calls an hour, and everyone said, “I took the product out of the box and it was cracked”? Now you're probably headed to manufacturing faster than you can hang up the phone and say, “Thanks, let me look into that right away.” One instance of a cracked product might just be a shipping accident; 100 calls per hour about cracked products means there's a good chance that there's a problem.

We call the set of initial statements or instances the premise (a customer called about a cracked product); the outcome (product is defective) is the conclusion. The stronger the premise (100 customers called with the problem, not just one), the more confidence in the conclusion (we really have a problem here).

There are a few important points to remember:

- When it comes to inductive reasoning, the outcome isn't guaranteed. There is only a probability that it will occur. In the preceding examples, another animal might not show up; your manager might not give you more work to do; or your call center might not get more calls this time. You're never absolutely sure.

- Almost all of your thinking is inductive reasoning. We come to thousands and thousands of conclusions a day using inductive reasoning. For example, your day begins by concluding to get out of bed.

- The stronger the initial statement (the premise), the more probable the outcome (the conclusion), and the higher your confidence.

Although few things are certain in our real world, many are highly probable. Unless something is absolutely certain, we use inductive reasoning to come to a conclusion. You make thousands of conclusions a day when operating in automatic mode—from what to wear and eat to which way to drive to what to say. You make nearly every one of these decisions via the process of induction.

It's All about the Premise

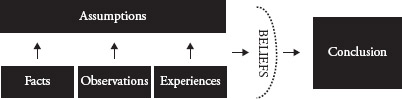

Remember, the stronger the set of initial statements (the premise), the more probable the outcome (the conclusion)—and the higher our confidence. The premise comprises facts, observations, experiences, beliefs, and assumptions (see Figure 15.1). It's all about the premise; this is where the process begins, and is the foundation of every conclusion you make. Although we still need to define the preceding terms, Figure 15.1 shows how you use each of these components in your premise and how a conclusion follows.

You make assumptions using facts, observations, and experiences as the foundation. You then come to a conclusion that your beliefs have filtered.

We'll come back to this diagram in “The Conclusion: Putting It All Together” after we define these components.

The Takeaway

Almost all our thinking is inductive reasoning. The process starts with a premise composed of facts, observations, experiences, beliefs, and assumptions. The stronger the premise, the more confidence you'll have in the conclusion you form.

Now let's take a closer look at the five components of a premise—what we've been referring to as the initial statement—and how it all works. Ready? Let's start with facts.