chapter eight General conclusion

So it is, said the Wise Eagle, that things never turn out the way you thought they would, which means you didn’t think right in the first place.

Darloz

Projects are much like hurricanes. They have a beginning and, fortunately, an end. They have a ceiling (they can go up to the troposphere) and a floor (the central pressure level, which is a key measurement of their strength). They are the results of causes, some of which are undisputed: sea surface temperature and vertical wind shear to name just two (the human influence and its participation in global warming is still being debated). They are unique and innovative in their own right. They are composed of recognizable characteristics: rotation, size, strength, vapor content, and so forth. You can infer them from their functional elements: (1) a storm surge (easily exceeding 20 feet of water pouring over the land for Category Five); (2) high winds, some recorded at over 170 miles/hour; (3) massive loads of rain water; and finally (4) tornadoes spawned from their release of energy on land. They are bound by seasonal variations, that is, by the duration and timing (e.g., the Atlantic seasonal hurricane season) resulting from the Earth’s movements, by their structure (e.g., what they can gather in terms of dust, heat, vapor, wind, etc.), as well as by their energetic qualities (e.g., an initial independent disturbance that eventually gets them churning out their power, their origin, their proximity to the equator and to land, etc.).

Hurricanes have, of course, impacts on human lives, nature, and infrastructure. As Hurricane Katrina has proved in the most cruel manner, they can hit where vulnerable points are (the inadequate levees in the case of New Orleans), causing havoc and suffering in their trail. They are part of a feedback system: they alter the course of climate, and climate changes, in turn, shape them somehow. That’s because they belong to a closed dynamic system: the Earth.

What if nature, in fact, never evolved based on an assumed random effect but rather on somewhat coordinated attempts to reorganize itself? After all, hurricanes displace massive amounts of heat from the tropics to the North Pole, for example, and in the process stir the sea, so that it produces, in the end, submarine conveyors that transport sediments and food for the various species away from that pole. What if nature operated on the basis of projects? We humans do just that, after all.

The difference between human projects and hurricanes is, evidently, that the former are aimed at curving points of vulnerability, be they a need or a problem. Levees in New Orleans are an engineering response to the threats of deadly hurricanes relentlessly taunting the Gulf of Mexico. Unfortunately, that response had its own points of vulnerability, as tragically demonstrated by the passage of Katrina.

Hence, there is no sensible solution other than to make sure that the project that is being envisioned is feasible, that is, that it will realistically address the point of vulnerability it seeks to combat, rather than being dotted with more points of vulnerability itself.

The present book took us on a journey into the realm of project feasibility and points of vulnerability. While scientific in essence, each chapter and case read much like a series of short novels that sought to solve the mystery of points of vulnerability. The hero has been the feasibility analyst and the numerous villains included stakeholders who, maliciously or not, were found to impede on the successful realization of the project.

Projects are everywhere. They even exist in the underground economy. The mob and the police have their own projects, which may increase my readership! In the 1970s, to take this example, Project Alpha was a covert operation with an initial time line of six months, which was thereafter extended. Because of budget constraints, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the New Jersey (USA) State Police had to cooperate in order to share costs. Norms of quality had to be met: the infiltrators had to look credible. The dragnet that was designed to catch the Mafia, which was occupied in particular with gambling, intimidation, sharking, and theft, was all based on mutual trust—between the FBI and the state police agents and between the members of the Mafia and their servicemen. Suspicion (read: apprehension) ran high on both sides of the equation. Gangsters looked for signs everywhere: the way certain cars were parked (police cars usually park outside coffee shops with the front of the car facing the exit, for quick pursuit) or the way “customers” sitting in a bar unwittingly looked at people walking in from head to toe (or, more matter-of-factly, from head to shoes!). The FBI and the police had, evidently, a hidden agenda. The setup relied on one initial infrastructure: a mock trucking company.

Whether in Africa, Canada, Haiti, or the United States, whether in an open or a closed, a legal, corrupt or black market economy, projects invade every aspect of our lives. Once a project is envisioned, the key question is: “Is it feasible?”

I believe that the present book has offered the reader a fair bit of information that can help with the management of projects (hopefully legal ones!), and in particular in preparing an ironclad feasibility study by taking into account points of vulnerability (POVs). I also suppose that at least some of the ideas and the results I discussed could be of use in the regular operations of small, medium, and large companies.

I had fun. I enjoyed a little zoological tour, being acquainted with bees, brown trout, cats, chimpanzees, crocodiles, donkeys, eagles, headless chickens, herring (certainly not red ones!), horses, gazelles, hungry tigers, lonely sheep, mice, minks, pernicious jellyfish, pigs, rare long-peak birds, snakes, some academics (!), squirrels, and white elephants! I analyzed a number of cases pertaining to a plethora of fields: Recycl’Art, Sea Crest Fisheries, the African and Haitian situation, the AFT boat-building company, the Boeing–Bombardier predicament, the cat litter box, the Champlain bridge, the Italian Floorlite improvement project, the marriage example, the mean jellyfish, the lavender manufacturing farm, the Maine East Pharmacy (MEP), the Mervel Farm, the Montréal International District (MID), the Montréal Olympic Stadium (MOS), the NSTP-Environ projects, the oil filter, the Québec Multifunctional Amphitheatre (QMA), the Stradivarius concert, and the TAPI project (see Brainteaser 8). Some of these projects were great successes, others catastrophic, and yet others potential successes or failures. I performed a number of field and laboratory studies, including one using functional magnetic resonance imaging—fMRI) and some tests in a cyberpsychology laboratory with which I work. I provided a large number of drawings, figures, images, pictures, and tables in order to render the content as concrete as possible. The objective was to make the reader feel immersed in the reality of projects, so to speak. Using the methodology called ‘data percolation’, I dug into all kinds of sources, including literature reviews and contemporary interviews. I provided tools, such as

A questionnaire (Appendix 5.2)1

Prefeasibility and feasibility templates (Appendices 2.2 and 3.1)

Reference tables (e.g., Appendix 5.3; Tables 1.5, 2.8, 2.13, 2.14, 3.4, 4.1, 4.4, 4.6, 4.8, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, and 6.32)

SVOR (Table I.12)

The summative triangle (Figures 3.11 and 3.12)

Three core models (Figures 1.6, 2.3, and 5.4)

I came across a great number of passionate people, including Tutankhamen (he didn’t talk much though)!

I certainly favored a multidisciplinary approach. I touched in particular on project management, of course, but also on chess and football strategy, economics, ethology, marketing, meteorology, neuropsychology, organizational behavior, psychology, sociology, and statistics. I proposed some mathematical formulae in an attempt to describe how behaviors actually emerge, develop, and become extinct within the confines of the closed dynamic system of a project. Are these formulae the ultimate truth? Hardly. However, they are an honest attempt at modeling the reality of project feasibility.

I readily acknowledge that the content of this book has its limitations. I expressed a number of hypotheses, and I worked around my core model in order to focus on the constant that keeps emerging through my data set, [k = 1.3]. My effort should be viewed as an exploratory one; much research remains to be done and much constructive debate can ensue that will allow for the betterment of my approach. I tried to stick to conventional wisdom, and to express project management phenomena in a manner that can be generalized. In fact, many project managers have told me that I had put down, in a formalized way, what they were experiencing but never had a chance to put into words, for lack of existing relevant vocabulary.

Being both a business analyst and professor, I had, at heart, to communicate without adopting a heavy academic style; rather, I opted for imagery such as hungry tigers, and for humor, such as the third eye on the back of Caesar’s head, which Cleopatra may not have found very attractive! In fact, I improved the perceived value of the present book by merging two outstanding features: first, it is a book of knowledge in itself, and second, it can serve as a sleeping pill if you read it all at once!

I thought I would summarize the present book by going over, once more, the novel ideas I presented; the key components of a feasibility study as outlined in the previous chapters; the six laws of project feasibility as we discovered them; the managerial recommendations I made with great humility and without any intention of imposing my viewpoints; the lessons learned about the POVs; and finally the existing theories that I challenged.

8.1 Novel ideas

I presented a number of novel ideas and tools, such as (1) the concepts of walls (related to calendars), ceilings (related to costs), and floors (related to norms of quality); (2) the five frames of a prefeasibility analysis; (3) the four Ps of project feasibility analysis; (4) the g-spread; (5) the summative triangle; (6) the notion of ‘bad apples’; (7) the PCI Index; (8) the six Ps of strategic project management, which includes the SVOR analysis (with the mathematical links between opportunity, risks, strengths, and vulnerabilities); (9) the triangle of value (perceived, added, and residual) as it is linked to the triple constraints; and (10) the barometer of Trust.

8.2 Key components of a project feasibility analysis

I found key components of a project feasibility analysis, including: (1) the role of the constant k; (2) the role of stars and hungry tigers; (3) the six core competencies model; and (4) the role of numerous mathematical functions such as the Satisfaction curve.

8.3 Six laws of a project feasibility assessment

I identified six ‘laws’ of a project feasibility2 assessment that can serve as a general guide for double-checking a feasibility study. The first law of project feasibility (the law of positive and negative forces) states that a project is not feasible if the positive forces (which play in favor of the project, i.e., which maintain a functional g-spread) are smaller than the negative forces (which play against the project, such as risks). The second law of project feasibility on dependencies notes that the higher the dependencies between the project’s tasks, the more vulnerable the project is. High task interdependence engenders high potential vulnerability. The third law of project feasibility (the law of points of vulnerability) stipulates that the higher the total vulnerability is (the sum of all g-spreads along each of the transformation stages) and the weaker the remedial actions are, the less the project is feasible. The fourth law of project feasibility (the law on the Forces of Production) posits that the more FPnc > FPc, the more the probability of collapse augments. Notably, I referred to a deadly interplay between FPnc and poor planning. The fifth law of project feasibility (law on conflicts) states that the more the wrangling among stakeholders is intense, frequent, and covers critical issues, the less likely the feasibility of the project. The sixth and final law of project feasibility (law of complexity) assumes that the more complex a project is, the riskier it is and the more POVs it contains, and the more probabilities of failure exist.

Window of opportunity.

I also described how the law of Apprehension, which applies to other fields (such as behavioral finance), is present in every aspect of life.

8.4 Managerial considerations

To address the challenges of contemporary projects and feasibility analyses, I humbly proposed a number of key managerial recommendations. In the general introduction of this book, I concluded that (1) POVs cannot be ignored; (2) POVs exist for each of the four Ps—Plans, Processes, People, and Power; (3) managers must strive for a Total strength strategy (Dominant + Contingency + Short strategies); and (4) risks cannot be assessed without evaluating POVs at the same time.

In Chapter 1 on Plans, I suggested the following: (1) ensure full and accurate definition of the project; (2) understand inputs and outputs; (3) identify the three types of values: perceived, added, and residual; and (4) examine functionality, design, and costs.

In Chapter 2, also on Plans but with an emphasis on prefeasibility, I concluded that (1) all four Ps have to be evaluated in a prefeasibility study; (2) poor planning along with the presence of Unfits (uncontrolled Forces of Production) is to be avoided; (3) all five frames of analysis as a way of shedding light to uncover dark spots have to be used; and (4) an aim for a robust strategy is to be favored.

In Chapter 3 on Plans and feasibility analysis, I showed that it was advisable to (1) clearly define the products, the organization, and the work to be done; (2) laser focus on what can go wrong in search of POVs; (3) face risks and reduce vulnerabilities appropriately, and build on strengths while answering adequately to opportunities; (4) use both a detailed and a global picture approach; (5) evaluate the transformation stages in terms of calendar of tasks and activities, costs, and norms of quality; (6) actively scrutinize the causal links between the tasks; and (7) use the summative triangle to render the concept in a simple format that everyone can comprehend.

Chapter 4 on Processes led me to the following recommendations: (1) reduce all process flows to causal relationships; (2) seek equilibrium; (3) measure variance punctually and longitudinally; (4) check for risks, POVs, and errors; (5) use modeling and modeling language to extirpate hidden POVs; and (6) zoom in on the three fundamental preoccupations, which are the managing and minimizing of risks, POVs, and ɛ, the error term.

In Chapter 5 on People, I said that (1) four kinds of stakeholders must be taken into account—customers, suppliers, regulators, and ‘bad apples’; (2) the manager should do all he can to minimize the influence of Unfits (FPnc) and bad apples; (3) the manager should observe, observe, and observe again; and (4) the manager must master the project from a parametric, conceptual, and process point of view and seek to be in control, transparent, and fair. He/she should expect from all personnel at all the levels of the project to display trust, collaboration, and commitment. I noted that hostility (especially instrumental hostility) destroys a work atmosphere and that a dynamic Point of Equilibrium is more important to achieve than everyone’s satisfaction.

In Chapter 6 on People in action, I concluded that (1) equilibrium in project management is a dynamic event; it is constantly challenged by circumstances and people; (2) three simple questions may be posed to rapidly assess a project: (a) “Are adequate managerial skills in place?”; (b) “Do all the stakeholders trust the project and each other?”; and (c) “Are all the necessary direct and indirect resources available (|R and |T)?”; (3) top performers must be quickly identified and encouraged for what they bring to the team; (4) a manager should scour instrumental hostility and deal with elusive agendas and dysfunctional Forces of Production; and (5) he/she must address problems and squabbles right away so as not to allow things to become rotten (they inevitably will).

Chapter 7 on Power can be summarized by the following: (1) the real power is the capacity of people in a position of authority to address POVs; (2) strategic project management is looking at projects from six angles: Plans–Processes–People–Power (four Ps), pessimistic–realistic–optimistic scenarios (PRO), product–organization–WBS (POW), present work psychodynamics (PWP) (six core competencies model), points of vulnerability (POVs) using SVOR, and dynamic Point of Equilibrium (POE); (3) aiming to simplify complexity; (4) when negotiating, shying away from asymmetry of information; (5) realizing that decisions are influenced by a positivity bias that the project feasibility analyst should be weary of; and finally (6) having three fundamental preoccupations: (a) risks, (b) POVs, and (c) the error term ɛ.

8.5 Lessons learned about POVs

Regarding what we have learned about POVs, this amounts to the following. In the preface, we saw that POVs make for predator–prey dynamics—they are costly, they are tantamount to poor loss management, and they are created by humans. In the general introduction, I suggested that POVs that are not managed impair managers’ Dominant and Contingency strategies; POVs that are managed can help a manager achieve success; POVs spell trouble down the road; they are present in any project at a minimum level of 4%–7%; they exist within each one of the four Ps; POVs have degrees of gravity; they are sensitive to the triple constraints, but are mostly associated with costs; they exist in both national and international projects; POVs can be somewhat tricky; and they are directly connected to risks.

In the first chapter, I concluded that POVs are seldom discussed in the scientific literature and in feasibility studies; when internally controlled, they express a Contingency Strategy (CS); they are exemplified by such an element as the Unfits (uncontrolled Forces of Production, FPnc); they can be hidden; if deciphered, they can present a dual advantage: the possibility of reducing costs (by way of finding inventive ways to rethink a particular process, for example) and to prevent the rise of costs due to processing mishaps; POVs can sneak in along the process chain inputs–transformation–outputs; they can compromise a project after its completion; they foster uncertainty; they are associated with ambiguity and unknown variables; they are hosted or fostered by intangibles; they require an analysis of the motivation (the opportunity) behind the project from the point of view of each important stakeholder; POVs can be spotted by a large difference between perceived value, added value, and residual value; they typically occur when a latent need and the corresponding innovation don’t match; and they are also associated with a short strategy (when tackled, they end up in the Contingency strategy area).

In the second chapter, I showed that POVs can appear in any of the eight different contextual risk areas; they may include a nonrealistic plan and/or a poorly articulated plan, diffuse measures of success, an inadequate change process, incompetent managers, and a lack of safeguards to prevent derailment; POVs may be uncovered by resorting to qualitative measurements; they may also be unmasked through proper modeling; they exist because people do not think of them, do not wish to admit that they exist, or else ignore them; they often result from poor planning and an inadequate workforce; they can be subdued in a feasibility study by way of: (plan) a well-defined charter, objectives, impacts, and roles; access to financial resources; detailed resource requirements; the establishment of norms; a realistic calendar; an articulate budget; (processes) a formal methodology; the use of proven standards, procedures, and technology; a reliance on solid infrastructures; (power) resorting to experienced project managers; and adequate control procedures.

In the third chapter, I showed that POVs affect costs most directly; they are minimized by great managers, thus allowing them to better handle the triple constraints; they have a tendency to throw the project outside the ‘football’ formed by the three constraints, in an area that I call ‘chaos’; they are actuated by the presence of risks; they can be detected by examining everything that can go wrong (PRO system); they are highlighted by the fact that a promoter cannot measure his/her endeavor or else that he/she doesn’t care enough about finding ways to measure them other than financially or operationally; they develop because there are no measurements; they are theoretical in nature at the planning stage; they start being active once the [effort | time] curve adopts the linear ascending shape; they represent a source of clear and present danger during the stages of mobilization and deployment; they are sometimes discovered after the project is completed; they are temporally spaced along the calendar of tasks; they are related to proper description during the planning stage, their influence during mobilization, their level of causality during implementation, and their timeliness during completion of the project; they can compromise POW; and they are closely associated with cost control management.

In Chapter 4, I showed that POVs become obvious when the direct linear process starts going awry; they can be awoken by uncontrollable factors; they can be detected when the project starts to be both ineffective and inefficient; they are brought under control when straight, direct, and diagonal processes work in tandem to achieve a result that is close enough to the intended output; they are hidden in a variety of entry points, end points, or nondirect flows, and will likely remain undetected until after they cause damage to the project; they always affect one or more than one of the three constraints: time, costs, and/or norms of quality; they wreak havoc in the transformation phase of the project when the most critical linkage level is reached; they have four levels of criticality (low, moderate, serious, critical) depending on the nature of the causal bond in the process; they can be outlined by the causal links appearing in the process (especially in a critical path assessment); they are more dangerous on the critical path than on paths where there are mediating options; they cripple any process system; they can be awoken by the catalyst effect of a moderating variable; they are sensitive to the type of process bond (D, T, I, C) in place; they grow like mushrooms (in dark areas!); they can be anticipated to a certain degree; they can be identified through my modeling technique; they are to be included in a manager’s list of duties, which also includes: controlling the Unfits (FPnc), eliminating errors, harmonizing the four Ps, managing risks, and relying on proper infrastructures; they have two faces: one with respect to the error term ɛ (linked to efficiency), and one with respect to the final outputs (linked to efficacy); they are temporal: they have to be measured in regard to inputs, outputs, and to the error term ɛ; they are empowered by the lack of forecasting of outputs; they are linked to the Blindness curve; they are linked to utility (a zero difference between beginning and end POVs = high utility); they are not classified as magic moments; they can be somewhat reduced by having some excesses Rn; they are at the highest level when far from the POE; they can hardly be measured directly because they are often buried; they can be uncovered by analyzing the POE; they can somewhat be represented by the g-spread, and can be viewed punctually and longitudinally.

Chapter 5 taught us that POVs: are inherent in the case of competing interests among stakeholders; they increase as FPnc > FPc; they go hand in hand with Trust in a psychodynamics context; they can be estimated by looking at curriculums and answers to particular psychometric tests; they are closely associated with the barometer to Trust; they have an impact on a project outcome along with risks; they are part of Apprehension when internalized; they drive people’s behaviors; they are often known to people, consciously or not (gut feeling); they weaken a Dominant strategy; they are linked to Trust given positive intentions; they influence commitment; they can reach a value of 2.3, at which point the project system crashes; they can have a value of zero which means zero Apprehension; they are fostered by lack of due diligence/vigilance; they come to light when people sit on their laurels; they are minimized at the dynamic POE; they are related to compliance/resistance to change (the more POVs, the more resistance); they are sensitive to cultural contexts; and they are an integral part of human behavior.

In Chapter 6, I outlined the fact that POVs may play against People’s own welfare; they diminish with People’s commitment; they are related to the constant k; they are best tackled by top performers; they are linked to nefarious behaviors; at their peak, they point to the fact that there are people wanting to intentionally disrupt the project (Instrumentally hostile individuals or hungry tigers); they are related to |R and |T; they foster the normalization of conflicts; they affect trust, which, being intimately bonded with a sense of fairness and collaboration, impacts conflict levels; they foster blind management when left unchecked; they are in part unpredictable; and they demand employee training and the supply of |R.

Finally, in Chapter 7, I showed that POVs can be enhanced by the lack of balance between control and transparency; they can be addressed by real power; they affect both perceived and added value; they are numerous (everything that can go wrong); they are masked by the lack of proper definition of the key attributes of the project; they must be measured with the proper instruments; they must be measured for their description, presence, and importance; they are fostered by convoluted plans; they may be highlighted by comparing contrasting cases/projects; they have a greater chance of occurring when there is disproportionate weight given to a particular criterion versus the others; they obstruct the chances of success as the project is less and less rooted in reality; they can be somewhat assessed by looking at walls, ceilings, and floors; they can be identified by setting all production parameters at their maximum operational level and then one notch above and by seeing which one will likely fail first; they can be highlighted using diverse types of analyses (e.g., multicriteria analysis); they are exemplified by biases such as the positivity bias (overoptimism), Blind trust, narrow-mindedness (tunnel vision), and prey positions; they are related to integrity taken individually, to exchange of information (EI) taken individually, and to the mutual influence of integrity and EI; they are, in the best of scenarios, acknowledged by project managers; and they are part of the triple core functions of a project manager (managing and minimizing: risks—related to calendar, POVs—related to costs, and the error term—related to norms of quality).

Put differently, POVs (with each subsection presented in the chronological order the features appear in the book):

Characteristics

Description

Identity

Are an integral part of human behavior.

Are not classified as magic moments.

Are part of Apprehension, when internalized.

Are part of the triple core functions of a project manager (managing and minimizing: risks—related to calendar, POVs—related to costs, and the error term—related to norms of quality).

Can be somewhat tricky.

Are linked to Trust given positive intentions.

Go hand in hand with Trust in a psychodynamics (work culture) context.

Are numerous (everything that can go wrong).

Grow like mushrooms (in dark areas).

Have three characteristics: identity, presence, and importance.

Are temporal: They have to be measured in regard to inputs, outputs, and the error term ɛ.

Represent a source of clear and present danger during the stages of mobilization and deployment.

Are related to proper description during the planning stage; their influence during mobilization; their level of causality during implementation; and their timeliness during completion of the project.

Presence

Exist in both national and international projects.

Exist within each one of the four Ps.

Are often known to people, consciously or not (gut feeling).

Can be represented by the g-spread.

Are seldom discussed in scientific literature and in feasibility studies.

Are sometimes discovered after the project is completed.

Are temporally spaced along the calendar of tasks.

Can appear in any of the eight different contextual risk areas.

Can be viewed punctually and longitudinally.

Can sneak in along the process chain inputs–transformation–outputs.

Importance

Drive people’s behaviors.

Are more dangerous on the critical path than on paths where mediating options exist.

Are present in any project at a minimum level of 4%–7%.

Are theoretical in nature at the planning stage.

Are, at their peak, the fact of people wanting to intentionally disrupt the project (hungry tigers).

Can reach a value of 2.3, at which point the project system crashes.

Have degrees of gravity.

Have four levels of criticality (low, moderate, serious, critical) depending on the nature of the causal bond in the process.

Increase as FPnc > FPc.

Start being active once the [effort | time] curve adopts the linear ascending shape.

Come to light when people sit on their laurels.

Causes and Triggers

Are activated by the presence of risks.

Are empowered by the lack of forecasting of outputs.

Are fostered by complexity.

Are fostered by lack of due diligence/vigilance.

Can be awoken by the catalyst effect of a moderating variable.

Can be awoken by uncontrollable factors.

Develop because there are no measurements.

Exist because people do not think of them, do not wish to admit that they exist, or else ignore them.

May be caused by a nonrealistic plan; a poorly articulated plan; diffuse measures of success; an inadequate change process; incompetent managers; and a lack of safeguards to prevent derailment.

Links

Have two faces: one with respect to the error term ɛ (linked to efficiency), and one with respect to the final outputs (linked to efficacy).

Are associated with a Short strategy (when not tackled).

Are associated with ambiguity and unknown variables.

Are closely associated with cost control management.

Are closely associated with the barometer to Trust.

Are directly connected to risks.

Are linked to hostile behaviors.

Are linked to the Blindness curve.

Are linked to utility (a zero difference between beginning and end POVS = high utility).

Are related to |R and |T.

Are related to compliance/resistance to change (the more POVs, the more resistance).

Are related to Integrity taken individually, to EI taken individually, and to the mutual influence of Integrity and EI.

Are related to the constant k.

Influences Sustained

Are sensitive to cultural contexts.

Are sensitive to the triple constraint, but are mostly associated with costs.

Are sensitive to the type of process bond (D, T, I, C).

Detection

Are at the highest level when far from the POE.

Are exemplified by biases such as the positivity bias (overoptimism), blind trust, narrow-mindedness (tunnel vision), and prey positions.

Are exemplified by such element as Unfits (uncontrolled Forces of Production, FPnc).

Become obvious when the direct linear process starts going awry.

Can be detected when a latent need and the corresponding innovation don’t match.

Can be detected when the project is both ineffective and inefficient.

Can be detected when there is disproportionate weight given to a particular criterion versus others.

Can be hidden.

Can be highlighted using various types of analyses (e.g., multicriteria analysis, SVOR).

Can be identified by setting all production parameters at their maximum operational level and then one notch above and see which one will likely fail first.

Can be identified through my modeling technique.

Can be outlined by the causal links appearing in the process (especially in a critical path assessment).

Can be somewhat assessed by looking at walls, ceilings, and floors.

Can be somewhat guessed by looking at curriculums and answers to particular psychometric tests.

Can be spotted by a large difference between perceived value, added value, and residual value.

Can be uncovered by analyzing the POE.

Can be uncovered by examining everything that can go wrong (PRO system).

Can hardly be measured directly because they are often hidden.

May be uncovered by resorting to qualitative measurements.

May be uncovered through proper modeling.

Strategies

Are best tackled by top performers (the Stars).

Are brought under control when straight, direct, and diagonal processes work in tandem to achieve a result that is close enough to the intended output.

Are minimized at the dynamic POE.

Are minimized by great managers who know how to handle the triple constraints.

Are to be considered by a manager along with controlling the FPnc, controlling risks, harmonizing the four Ps, relying on proper infrastructures, and eliminating errors.

Are, in the best of scenarios, acknowledged by project managers.

Can be addressed by real power.

Can be anticipated to a certain degree.

Can be somewhat reduced by having some excess (Rn).

Can be subdued by the proper balance between control and transparency.

Can be subdued, in a feasibility study, by way of: (Plans) well-defined charter, objectives, impacts, and roles; access to financial resources; detailed resource requirements; the establishment of norms; a realistic calendar; an articulate budget; (Processes) a formal methodology; the use of proven standards and procedures; the use of proven technology; a reliance on solid infrastructures; (Power) resorting to experienced project managers; and adequate control procedures.

Demand employee training and the supply of |R.

May be highlighted by comparing contrasting cases/projects.

Must be measured for their description, presence, and importance.

Must be measured with proper instruments.

Require an analysis of the motivation (the opportunity) behind the project from the point of view of each important stakeholder.

Can help a manager achieving success when well managed.

Can impair managers’ Dominant and Contingency positions when not managed.

Express a Contingency Strategy (CS) when internally controlled.

Impacts

Affect both perceived and added value (and, ultimately, the residual value).

Affect the costs more directly.

Affect Trust, which, being intimately bonded with a sense of fairness and collaboration, impacts conflict levels.

Always affect one or more than one of the three constraints: time, costs, and/or norms of quality.

Can compromise POW.

Can jeopardize a project after its completion.

Wreak havoc in the transformation phase of the project when the most critical linkage level is reached.

Foster uncertainty.

Diminish with People’s commitment.

Foster blind management when left unchecked.

Foster the normalization of conflicts.

Have a tendency to throw the project outside the ‘football’ formed by the three constraints, in an area called ‘chaos’.

Have an impact on a project outcome along with risks.

Influence commitment.

If tackled, can present a dual advantage: the possibility of reducing costs (by way of finding inventive ways to rethink a particular process, for example) and to prevent the rise of costs due to processing mishaps.

May play against People’s own welfare.

Obstruct the chances of success as the project is less and less rooted in reality.

Often result from poor planning and an inadequate workforce (dreadful combination).

Spell trouble down the road.

That have a value of zero lead to zero Apprehension.

That are hidden in a variety of entry points, end points, or non-direct flows will likely remain undetected until after they cause damage to the project.

Weaken a Dominant strategy.

Weaken any process system.

8.6 Theories challenged

I challenged some of the theories or methods put forth by other authors or sources, such as the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK). Examples include: (1) the notion of groups of processes in PMBOK; (2) the accuracy of the 10 domains of knowledge in PMBOK; and (3) the views on constraints in PMBOK 5.3

In some other domains, I opened some research avenues by proposing to reorganize the DSM-V nomenclature to fit the six core competencies model, and I postulated that oxytocin had to be considered along with cortisol, testosterone, and serotonin in order to fully comprehend the four basic coping mechanisms anchored in the hypothalamus. On this point, I hypothesized that in fact all four responses are ultimately defensive in nature, considering that Instrumentally hostile behaviors had one differentiating particularity: they are a delayed response that involves higher cognitive inputs. All four coping measures are meant to deal with POVs.

My comments and critiques were meant to be constructive and by no means must be deemed denigrating; it is by way of scrupulous analyses that knowledge progresses.

8.7 Cases and brain teasers

In the sections labeled ‘Case’ at the end of each chapter, I presented some real project cases as well as some challenging questions. Analyses of the cases and answers can be made available by the author upon request by the reader. I invite the reader to go through the cases and instinctively apply to them the knowledge that he/she has acquired in the introduction, the seven chapters and the conclusion of this book. Project management professionals (PMPs) will also find that they can apply PMBOK theory to these cases, as they are constructed to match some of PMBOK 5 content. I also added some “brain teasers” at the end of the present book to somewhat entertain the reader.

8.8 Humor

I have tried to make the reading both entertaining and serious. My use of dry wit should not be misinterpreted to infer that my discussion was not stamped with scientific rigor. Quite the contrary! I have researched extensively and looked at POVs in all kinds of scientific ways. Yet, I believe communication has to be lively and that it should raise interest. Communication is important. The author of this book, who stutters, confides:

“Communication and use of proper wording is crucial. You have to make sure your crew understands you loud and clear. To take a personal example, I told my wife on our honeymoon that I would I give her an orchid every week (she loves flowers). She misunderstood the word and has held me up to it ever since!”

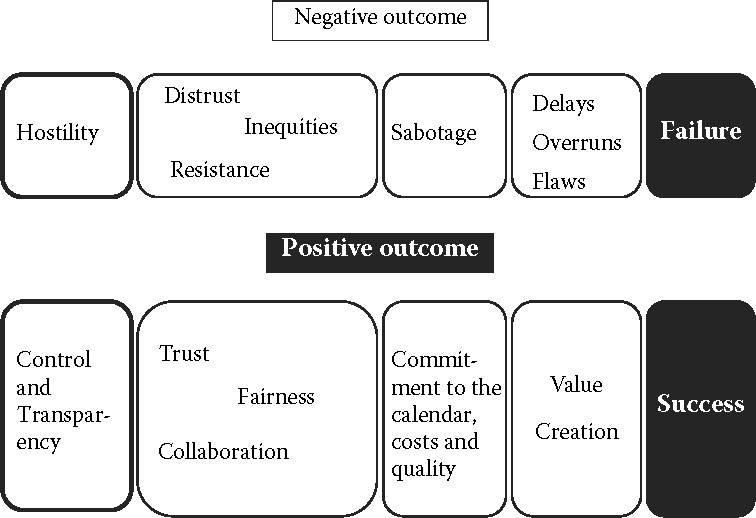

8.9 The future

There is no doubt that a fair amount of future work is advisable in order to develop the field of project feasibility analysis from the angle of POVs. We have learned throughout the present book that people commit to projects, but more particularly, that they commit to meeting the deadlines, to the tasks and activities (WBS), to respecting set cost limits, and to abiding by the norms of quality. In order to guarantee efficient commitment, there has to be collaboration among team members. However, collaboration is unlikely if there is no mutual trust and a sense of fairness in the general work culture (psychodynamics) of the project. Trust is negatively affected by apprehension, so that it is most important to get an unflappable grip on hostility and to be transparent within reason in order to make the project plan as limpid as possible for all stakeholders. I have tried to show that confrontational management encourages process and product flaws, which, of course, means that it leads to a reduction in quality. People have all kinds of ways of sabotaging their work—by conveying the wrong information, delaying outputs, procrastinating, spending time for personal reasons, and so forth. Goodwill, an intangible asset that I discussed previously, builds on the psychological core of trust, fairness, and collaboration.

I hope that this book provides an initial spark to encourage the effort of understanding the link between human behavior and relationships and quality outputs. Team efforts permeate every aspect of projects. Again, I do not pretend to hold the truth, or that this book is perfect. If it could merely serve the project feasibility analysts in one way or another, I would be pleased and would assume that I have achieved my modest goal. I hope that some of my imaginative ways of expressing some of my ideas—such as the “I gotta go” people, to take only this example—have made the reading enjoyable and memorable.

In summary, a project feasibility analyst looks for Dominant and Contingency strategies; he/she detects hostile and defensive positions that can jeopardize the project. He/she is aware of the need for Short strategies when difficulties surface. An analyst aims for robust project management, one that is able to deal with POVs ahead of time, whether this entails being agile on occasions or else standing firm in front of adversity. Think of a project as a football game: the team has to come together. It establishes a strategy to get to the finish line the best way possible, as pressured by time, and given physical energy (cost), quality of the plays, of the players, and of the Fits (you don’t want to put Joe Montana in a tight end position, do you?). You face adversity (the opponent in the football example) that you must respect and outsmart with the proper skills. When you score, everyone is proud and celebrates, possibly by the thousands. There are random setbacks, but you keep going forward, to the very last second. Your plays are realistic; you try to find a gap in the opponent’s actions and reactions, while managing and minimizing risks, POVs, and errors.

I invite the reader to apply the knowledge expanded in this book in real-life situations—there is no better way to integrate it and make improvements on it.4

Thank you for having taken the time to read this book and remember, despite the best efforts at due diligence, there will always be Fits and Unfits, hungry tigers and lonely sheep, stars and average team members, yet try not to hire any extraterrestrial creatures: they do great work but then they vanish without warning and without leaving any contact information!

8.10 Main hypothesized behavioral mathematical functions

8.11 Brain teasers

8.11.1 Brain teaser 1: The Bermuda Triangle

Comment on the following:

8.11.2 Brain teaser 2: PMBOK’s 10 domains

Comment on the following (see PMBOK 5, p. 99):

8.11.3 Brain teaser 3: PMBOK groups of processes

Going back to Chapter 2, about the idea of an oil filter for cars and trucks, please comment using the knowledge acquired in this book:

8.11.4 Brain teaser 4: Top performers

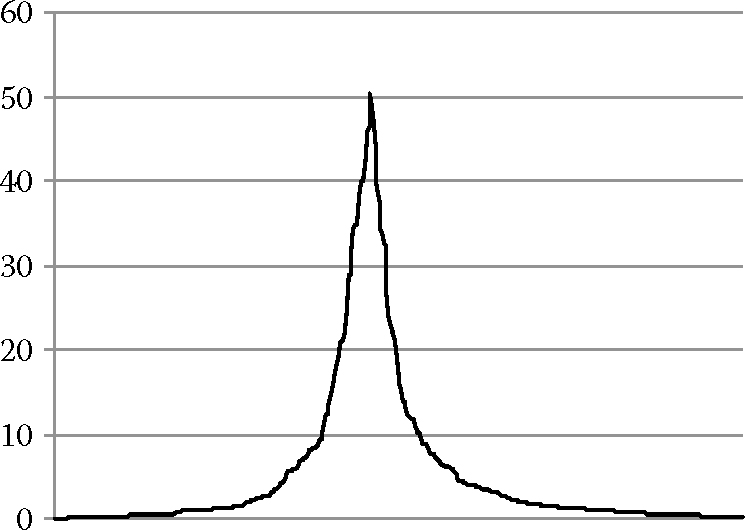

An analysis of top performers, regular performers, and below average performers for nearly 2000 team members, reveals the following graph, where the x-axis is the participants and the y-axis the project capability index (PCI), on a scale of 0 (poor) to 10 (excellent):

In addition, the distribution around the mean is as follows (with the x-axis being the standard deviation and the y-axis being the number of participants in percentage of the overall group):

Please comment on the observations you make referring back to Chapter 6, including by identifying the top performers.

8.11.5 Brain teaser 5: Behavior

A large multinational firm ran a study across its offices and a number of statistical outputs were produced. Please answer the following questions:

Based on the following graph, is it fair to say that Instrumentally hostile behavior is not linearly related to defensive behavior (x-axis = Defensive position; y-axis = Instrumentally hostile position; R2 = .094)5?

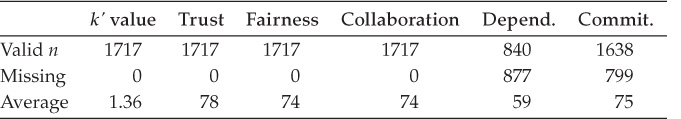

For 1717 respondents, the average k-value and the levels of some of the key constructs are as follows:

Please comment.

From the following table (and with the same group as above), can you infer the law of Apprehension?

Using the same database and looking at the following graph (x-axis = Trust, y-axis = Collaboration; R2 = 0.575), what can you conclude6?

When management plots Fairness (on the x-axis) against Collaboration (y-axis), it notices the following, on which please draw a conclusion (R2 = 0.531)7:

When management plots each of the four core types of coping mechanisms—hostile-offensive (instrumentally hostile), anxious, resisting, and fleeing—it obtains the following graph, about which please comment with respect to the k-value8:

Based on the following matrix, can management conclude that trust, fairness, and collaboration display an identical pattern (the behavioral core), while IP/DP is different, just like Commitment is also different?

Based on the following 3-D graph, is it fair for management to conclude that Trust, Fairness, and Collaboration form a single behavioral core?

8.11.6 Brain teaser 6: PMI talent triangle

The Project Management Institute (PMI) promotes the following concept, called the ‘PMI talent triangle’:

In particular, ask yourself: is “strategic management” not a component of overall business management? Can “strategic and business management” be associated with Plans, “technical project management” with Processes, and “leadership” with Power? Is “People” not missing from the model?

Please compare the PMI model with the following model, inspired from the MID (The Quartier international de Montréal) case:

8.11.7 Brain teaser 7: Organizational process assets

PMBOK 5th edition, p. 27, refers to “organizational process assets” as “(…) plans, processes, policies, procedures, and knowledge bases specific to and used by the performing organization. They include artefact, practice, or knowledge from any or all of the organizations involved in the project that can be used to perform or govern the project.”

Assume for a moment that plans refer to Plans as seen in the present book, processes, and procedures to Processes, and policies to Power, Would it be admissible to reformat the definition of organizational process assets as simply “project’s core Assets”? Would People not be missing from the equation? In other words, could we regroup the four Ps of project feasibility analyses under the heading “project’s core assets,” as follows (stylized model)?

8.11.8 Brain teaser 8: In sync or sink

In a project feasibility analysis, as we have seen throughout the present book, the experts try to determine ahead of time whether the four Ps are synchronized. Is the Plan in line with what can be realistically achieved? Are the processes, linear and diagonal, adapted to the Plan in a way that will make the project efficient and efficacious? Are the four groups of People (customers, suppliers, regulators, and bad apples) acting on the same understanding and with the same beneficial intentions, without hidden agendas? Is Power legitimate and focused on controlling hostility and on minimizing dissension? Failing proper alignment of means and ends, the project is likely to fizzle.

In the realm of project feasibility, the motto is “in sync or sink.”

A project is currently in the making whereby a $10 billion pipeline will be built to channel natural gas from the former Soviet state of Turkmenistan on a 1118-mile journey, going through Afghanistan and Pakistan to end in Fazilka, India. The so-called TAPI project would be operational by the end of 2019 and would be capable of transporting 24 billion gallons of gas a day.

After doing the necessary research and going through the four Ps, the POVs as well as the PRO scenarios, what would be your take on the “in sync or sink” point of view?

8.11.9 Brain teaser 9: Hostility and failure

Please comment on the following two models, based on what you have learned in this book (hint: find the type of bonds that exist between the constructs):

8.11.10 Brain teaser 10: A losing hand

Please adapt the following to a project you know:

8.11.11 Brain teaser 11: A winning hand

Please adapt the following to a project you know:

8.11.12 Brain teaser 12: Cleopatra’s necklace

Have fun with the following necklace that Caesar offered Cleopatra in an attempt to help her build a few pyramids:

8.11.13 Brain teaser 13: Who’s at work

Please look at the following and see if you can associate the various kinds of team members with people you know within your project endeavor:

8.11.14 Brain teaser 14: POVs

Try to make a list of everything you remember about POVs and compare it with the list found in the general conclusion.

Endnotes

- As mentioned, the questionnaire on psychological constructs can be made available by contacting the author and sending me, for example, a pre-paid Porsche Cayenne (marine blue please)!

- Not to mention the law of Apprehension (perceived threat), which is used in other venues such as psychology and behavioral finance.

- And of Mulcahy (2013).

- The “most effective learning is working in real-life situations” (Divjak and Kukec, 2008, p. 251).

- Residuals show a very normal distribution with no noticeable tendencies.

- Residuals display a normal behavior. F-value = 2,320.454, p = 0.000 (at 95%).

- Residuals display a normal behavior. F-value = 1,938.727; p = 0.000 (at 95%).

- Hint: In what quadrants/combinations are most of the respondents sitting?