Past Lessons: A Short

History of Design in

Activist Mode, 1750–2000

‘Designing is not a profession but an attitude.’

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

Design as ‘Giving Form to Culture’

The history of design activism is woven into a wider history of design. What can we learn from that history and how has it informed what design activism is today? What were the motives and intentions, and who were the target audiences and beneficiaries of the designers? How do the findings fit with the central idea of activism as an act to create positive social and political change?

It is important to enquire whether designers were specifically interested in changing the culture of design, i.e. the culture specifically belonging to the world of design, or a wider expression of culture as it belongs to the wider society, or indeed whether they were targeting both. Guy Julier differentiates between design culture as an object of study – as a process, as context-informed practice, as organizational or attitudinal, as agency, and as pervasive but differentiated value – and as an academic discipline (Table 2.1).1 Today’s omnipotent design culture, at least in the ‘developed’ North,2 plays a comprehensive role in suggesting and/or setting new values and, hence, inculcating societal change. Whosoever controls the designers – in modern capitalism that role generally falls to business and government – controls to a large degree the expressions and evolution of the design culture. The idea of design culture as an agency of reform (or even revolution) directing design towards greater and more direct social and environmental benefit, indicates the necessity to include wider societal representation and control of design activities. Does design history reveal these past ‘agents of reform’?

How far back we care to take the ‘past’ in referencing design is a moot point. ‘Design’ appears to have entered language and been given etymological birth in the Italian Renaissance as disegno, communicating the idea of drafting or drawing,3 but arguably did not find its way into general use until the first rumblings of the pre-industrial revolution in the mid-18th century.4 However, Sparke notes: ‘The designed artefact is on its simplest level … a form of communication and what it conveys depends on the framework within which it functions.’6 This acknowledges that any artefact communicates and embeds design, and that designed artefacts predate the era of the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution on which so much design history is focused.

Interpretations of ‘design culture’

an ‘object of study’ A design culture located in communication; something that is all around; an attitude; a value; a desire to improve things; existing at the local level; embedded in the working systems, knowledge and relationships of designers and design users; as a form of agency, ‘encultured’ design; directed towards future global change and a generator of (new) value; as a means to herald changes in a wider world; a ubiquitous presence; study of the material and immaterial aspects of everyday life; articulated through images, words, forms and spaces and it engages discourse, actions, beliefs, structures and relationships; motivated by concepts of value, creation and practice | |

| As ‘process’ | A design culture described by the contextual influences and contextually informed actions within the development of a design; systems of negotiation that define and frame design artefacts; process produced within and by a network of everyday knowledge and practices that surround the designer |

| As ‘context-informed practice’ | A design culture concerned with collectively held norms of practice influenced by geographical context of the local and/or the globalized, dominant, mainstream forms of practice; as a forum and platform; embraces notions of ‘creative industries’ as agents in business organization and ‘brand stewardship’ |

| As ‘agency’ | A design culture as an attitudinal marker for an organization and/or design engaged towards direct social and environmental benefits; a ‘way of doing things’; context as circumstance not a given; a change agent |

| As ‘pervasive but differentiated value’ | A design culture going beyond traditionally held notions of ‘excellence’, ‘innovation’ or ‘best-practice’ able to create specific and designerly ambience |

As an ‘academic discipline’ Not ‘design culture’ but ‘Design Culture’, to sit alongside Visual Culture, Cultural Studies, Media Studies and even Design History; moving from an emphasis of the ‘reading' of an image to a culture that is three-dimensional, equally tactile as visual and textual, all engulfing, lived in and directly encountered rather than as a (sole visual) representation; 3D visual artefacts that are not only ‘read’ but experienced within structured systems of encounter within the visual and material world; the study of design primacy for establishing symbolic value, a productive model of styling, coding and effective communication; designing an ‘aestheticized state’, commodifying the visual to meet modern capitalism's imperative; where in the new conditions of design culture, cognition becomes as much spatial and temporal as visual, embracing reality and virtual reality | |

| Source: Julier (2008)5 | |

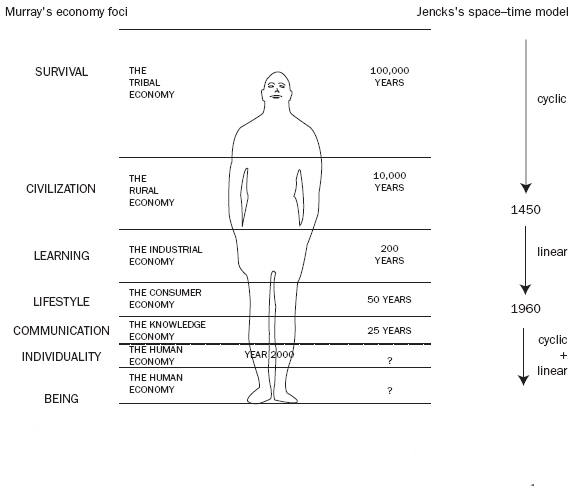

How has the role of design shifted through these eras? Figure 2.1 brings together the work of the Postmodern critic Charles Jencks with some concepts developed by brand consultant Will Murray.7 Jencks, in his landmark book What is Post- Modernism?,8 indicated that human concepts of time and space have gone through several phases. The first phase concluded around 1450 with the emergence of the Renaissance and the concept of ‘linear’ time–space, the notion of progress. This era signalled the end of ‘cyclic’ time–space that had kept man in empathy with nature’s rhythms. The birth of the Industrial Revolution literally accelerated the idea of progress and rapidly evolved design praxis (theory and practice). A further gear change in the time–space model happened in 1960 when the earlier ideas of 20th century modernity (with its roots in the late Medieval period and then the Enlightenment) were rejected in favour of a populist, pluralist Postmodernity with a concurrent ideological shift from mass consumption to individualized consumption. Murray looks back even further and suggests that societies are actually ‘economies’. As one society merges into another society we are really seeing shifts in economic models as a fundamental driver. Over the past 10,000 years there has been a consistent trend – the lifespan of these economic models is getting shorter (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1

How has the role of design changed over time with successive economies and space–time models?

As design helps materialize a ‘culturally acceptable’ form to represent the economic model,9 then design has evolved with these economic models and with our psychosocial perceptions of this rapidly changing world and its new time–space perceptions.

Design has occupied this central role as mediator of cultural acceptability and therefore provides a regulatory service in production and consumption. This role has shifted in three major phases between 1750 and 1990.10 The first phase, 1750–1850, heralded spectacular developments in agricultural equipment, the steam engine and early models of industrial manufacturing in the great ceramics companies of the Staffordshire Potteries, such as Wedgwood. The second phase, 1851–1918, commenced with the world’s first trade fair, the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace, London, representing an industry servicing the production and consumption boom of the European powers as they exploited their colonies for raw materials and labour. World War I, 1914–1918, shifted the global order and heralded the third phase in the history of industrial design, 1918–1990, where various design movements and groups juggled for supremacy throughout the 20th century. In each of these phases, the products (objects of production) become texts in ‘circuits of culture’.11 These artefacts are texts, representations that live within cultures, inform identities and social relations, and generate feedback to the next generation of production. John Wood sees design as a ‘wise regulation of dynamic elements’ where ‘form giving’ controls not only flows of materials in goods and products, but also controls the awareness and regulation of perceived value and hence the next cycle of ‘form giving’.12 Tony Fry neatly encapsulates all these circuits and flows with the beautifully simple phrase, ‘design designs’13 recently interpreted as ‘design as preconfiguration and directionality’ with the capability to influence what we choose to design and what happens next.14 Perhaps this preconfiguration could be interpreted as ‘memes’ – units of information and units of cultural transmission that explicitly and implicitly guide behaviour. Wahl and Baxter suggest that real forms are in themselves memes, but also carry a second meme, a vMEME or value meme.15 In giving form to the dominant socio-political and socio-economic norms, design simultaneously confers meaning and values, and affirms the dominant paradigm. Contention of the dominant paradigm implies the existence of a counter – narrative(s). Do these examples exist in design history and, if affirmative, how do they reveal themselves under the lens of sustainability as acts of design activism? How have these instances attempted to preconfigure and direct design, and the wider, culture?

A summary of the main design movements, groups and initiatives is given in Appendix 1 together with a brief analysis of the motivations, intentions, target audience and beneficiaries of their activities. Their achievements are also viewed through the lens of sustainability, so the outcomes are viewed in relation to positive economic, ecological, social and institutional contributions.

1750–1960: Mass Production

and (Sporadic) Modernity

The steam engine came of age in 1740 in Great Britain heralding a new energy source to drive new visions of mass production involving the local, regional and international transportation of materials, often over great distances, to a centralized factory. Here labour, formerly deployed on the land but driven from it by the introduction of mechanized equipment, worked with new steam-driven machinery to produce the goods for populations at home and overseas, the latter busily expanding and exploiting the first truly global business of Empire. In 1759, Josiah Wedgwood established his innovative ceramics business in the Potteries in Staffordshire, England.16 He was the first entrepreneur to achieve mass production of beautiful, affordable tableware, and set a model for mass production that still exists today.

In just 100 years, the physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual landscape of Britain had changed dramatically.17 This was lauded and celebrated in the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London’s Crystal Palace – a building that was remarkable in itself for being a modular flat-pack construction of steel and glass predominantly made in Birmingham, central England and transported to the capital by canal barge and horse-drawn transport. Surely this represented a positive design contribution to society, a vision of man taming nature and forging progress? Not everyone agreed. Early dissenters included Augustus Pugin and John Ruskin who critiqued the poor quality of the industrial goods on display at the Great Exhibition and the crass ornamentation, which they perceived as a cacophony of visual discord. These were the first design activists prepared to stand up to the Industrial Revolution juggernaut. Pugin and his colleagues set the tone for later dissenters who found their voice through William Morris, who established his own company in 1861 – Morris, Marshall & Faulker & Co – intent on promoting a revitalized vernacular simplicity combined with excellent craftsmanship. Morris and his colleagues extolled the virtues of these new ideas of craft as a means to promote social cohesion. Here were the founders of the late 19th-century British Arts and Crafts movement, the first design reformers intent on contributing to positive social change through improved design of artefacts, textiles, wallpapers and buildings. Sadly, their ambition outstripped their effectiveness. Morris and his followers encouraged artists to get out of their academies and immerse themselves in more prosaic production activities. He also galvanized the Arts and Crafts Guilds to organize themselves, and set standards of quality for both design and production. However, the outputs of their efforts could only be afforded by the bourgeois. More progressive thinkers in the movement, such as Charles R. Ashbee and Gordon Russell, established rural furniture manufacturing operations in an attempt to create more affordable products. Yet, the rampant industrialization and commercialization of Victorian life was largely untouched by these initiatives. There was, however, an unseen legacy. This early design movement is credited with stimulating and provoking thoughts among artists and designers throughout Europe, laying the foundations for various expressions of Art Nouveau and, in the first decade of the 20th century, the Vienna Workshop, Austria, and Deutscher Werkbund, Germany. The Deutscher Werkbund, 1907–1935 and 1947–present, emerged out of the expressive Jugendstil (representing Art Nouveau) to become the first significant organization to exploit and communicate the power of design as a vehicle for improving people’s lives. The early reforms of the Werkbund were celebrated by Heinrich Waentig noting that ‘a simple form, imposed on everyone, could produce ‘the most complete and noble overcoming of class conflicts’, clearly enunciating the socialist ambitions of this design movement.18 Functionalism demonstrated a new German idealism, but also drove darker ambitions of imposing artistic imperialism that emerged over the course of the next two decades.

Existenzminimum and other socially orientated housing projects by the Deutscher Werkbund

With the rise of national German folk culture and a concurrent socialist ideology, the Werkbund’s remit was focused on achieving good design with utilitarian production methods that maximized quality but retained affordability. A leading exponent of this affordable but functionalist design, with its socially conscious imperative, was Richard Riemerschmid accompanied by Bruno Paul, Peter Behrens and Josef Maria Olbrich working alongside established and respected manufacturers. Members included artists, designers and architects, including Walter Gropius, later to become the founding director of the Bauhaus. After a landmark exhibition in 1914 in Cologne – the Deutsche Werkbund-Ausstellung, showing Gropius’s steel and glass factory (and its improved conditions for production and the workforce) – the Werkbund’s popularity was assured and by 1915 it had attracted nearly 2000 members. In 1924, under the helm of Riemerschmid, the Werkbund published Form ohne Ornamen (Form without Ornament) heralding the foundation of early Functionalism. In 1927, the architect Mies van der Rohe coordinated, on behalf of the Werkbund, architects from all over Europe to work on the Weissenhofsiedlung, a housing estate in Stuttgart. Interiors were fitted with the steel tubular furniture of van der Rohe, Mart Stam, Marcel Breur and Le Corbusier – some of the avant-garde of Modernism. A similar ideology was rolled out for the Existenzminimum apartments for low-wage earners in Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Dessau, Breslau and Berlin. While the idea of social housing was not new (in England visionary social housing was the ambition of the US philanthropist George Peabody, who formed the Peabody Trust in 1862, and W. H. Lever who developed a model village at Port Sunlight by Lever Brothers in 1888), the belief that design of space, light and the component furnishings could elevate the quality of life of the inhabitants was radical.

The illustrious history of the Bauhaus, its directors and students, has rightly garnered much attention from the design historians in its pivotal role in establishing the rationality and efficiency of the Modern movement’s modes of design and production. In effect, this was the third era of modernity culminating in the ‘designability of everything and everyone’ – the first and second eras of modernity stretching from the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment.19 Yet the Bauhaus was a quixotic institution subject to at least five phases of growth and change, often instigated by each director responding to internal and external political pressures. It was during the directorship of Hannes Meyer, from March 1928 to July 1930, that the Bauhaus enjoyed its most socially proactive phase. Meyer was a steadfast proponent of affordable design and architecture for the working classes with his slogan ‘popular requirements instead of luxury requirements’.20 Meyer was perceived in retrospect as one of the most important Functionalists in the architecture of the 1920s.21 In 1929, he oversaw the design of the Trades Union School, Bernau, Berlin and the fixtures and fittings for the People’s Apartment. The furniture was so diligently conceived that it could have easily been mass produced. A touring exhibition for the cities of Basle and Mannheim, organized by Meyer, included Gustav Hassenflug’s folding table and Marianne Brandt and Hin Bredendieck’s redesigned bedside light for the Kandem company (Figure 2.2). The aesthetic of these products reveals a seductive simplicity akin to the contemporary designs of a present-day IKEA showroom. This reflected Meyer’s beliefs that design could elevate the welfare of the people and it could harmonize the requirements of the individual with the community. Meyer’s commitment to socialist ideals even led him to take a group of students to the Soviet Union in 1930 under the banner of the red Bauhaus brigade – an act that may have eventually led to his dismissal later that year as the political climate changed in Germany.

It seems Meyer was, under the preliminary terms of design activism defined so far, the Bauhaus’s lead design activist. Despite his intentions, the measurable benefits of his endeavours were probably limited. While the quality of the Bauhaus’s output is uncontested, and the contribution made to the pedagogy of art and design is not in dispute, many of the activities only influenced a relatively small number of manufacturers and built developments. In short, the Bauhaus did not seem to directly touch many in society, although its ripples were surely felt. Perhaps the disbandment of the Bauhaus in 1933 meant that the full social potential of the experiment could not be felt. The dispersal of many Bauhaus luminaries to the US and other countries following the swing towards Fascism and World War II undoubtedly provided many international benefits, but the momentum of design as a positive social force was lost and along with it the central ideal of Modernism to improve the human condition. The radical underlying social agenda of the Bauhaus was rapidly commodified in the International Style, which was soon recognized as a vehicle for transnational companies to flag their modern ideals, but not necessarily their social mores.

Furniture for the ‘People’s Apartment’, Bauhaus touring exhibition 1929

From the 1930s to the 1960s, in the growing world of consumer products, Modernism took a few twists and turns through Streamlining, Organic Design, Utility Design, Good Form and Bel Design, and Good Design. Two of Organic Design’s great exponents deserve a mention for their consistent attempts to humanize the overtly functional codes of Modernism and their introduction of organic forms. Frank Lloyd Wright in the US cut his teeth with his Prairie Houses in and around the suburbs of Chicago, revealing his empathy for natural materials and light, born out of a sympathy for the Arts and Crafts. He brought a holistic approach combining the best of Modernism with nature’s own genius in each location, and later championed outstanding examples of Organic Design, such as the Guggenheim Museum (1943–1946 and 1955–1959). The other luminary was the Finnish designer, Alvar Aalto. Aalto’s genius was to see the use of natural materials and light as a humanizing element in design that offered psychological benefits over man-made synthetic materials. The Paimio Sanatorium, 1928–1929, for tuberculosis patients, is one of his most well-known early works. His eclectic forms for grand and modest public buildings, and a number of experimental private houses, indicated his human-centred version of the Modern movement, and ambition to improve people’s well-being through the very fabric of the architecture. While both these architects strove for buildings that made genuine attempts to improve wellbeing, and undoubtedly influenced the culture of architecture, their contribution to wider social benefits seems less easy to confirm.

In the pre- and post-World War II years, there was little dissent from the Modernist mantra, just the occasional voice or head raised above the parapet. Early environmentalists had spotted some of the problems inherent in industrialization and consumerism, and the insatiable demands on nature’s resources and ecosystems. Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac introduced the concept of a ‘land ethic’, calling for man to adjust his presumption as nature’s conqueror to one of citizen sharing the Earth with a wider biotic community whose stability was in the citizen’s interest.22 An early advocate of treading more lightly on the planet’s resources was Richard Buckminster Fuller, a maverick whose work ranged from mathematics to architecture and industrial product design. Buckminster Fuller was environmentally and socially aware, proposing numerous concepts and realizing diverse projects that addressed eco-efficiency and affordability – many emerging from his Dymaxion Corporation, a name derived from ‘dynamic’ and ‘maximum’. Projects included prototype housing (Dymaxion House, 1927; Witchita House, 1945) and cars (Dymaxion Car, 1934). He popularized the concept of the light-weight, efficient geodesic dome and was not alone in his concerns for the welfare of the planet. In the mid-1950s, architect Richard Neutra unveiled his concerns in Survival through Design and Vance Packard wrote a withering trilogy of books exposing the deceit and lies of the consumer economy (The Hidden Persuaders, The Status Seeker, and The Waste Makers).23 But it took an angry post-World War II generation, and the emergence of new voices in ‘youth’ and ‘teenagers’, to foment social change and, finally, an interrogation of the dicta of the Modernists. They rejected the notions of an elite circumscribing and moralizing about what constituted ‘good design’ and embarked upon a design fiesta that marked the birth of the consumer economy, still with us today.

1960–2000: From Pop and Postmodernism to Postmodern Ecology and Beyond

The 1960s heralded a social, technological and environmental watershed. Here was a discursive climate from which an explosion of fresh ideologies resulted. The father of British Pop Art, Richard Hamilton, posited the idea that values are explicitly and openly debated in a genuinely democratic society: ‘An ideal culture, in my terms, is one in which awareness of its condition is universal.’24 The elitist Modernist principles adapted by so many of the industrialized countries had failed to respond to the paradigm-shifting consequences of the emergent post-war consumer economy and its resultant outputs of mass culture and mass taste.25 A new design language, ‘pop design’ emerged with its central tenets of diverse expression, symbolism, ephemerality and fun.26 Parallel to the mass-market exploitation of pop design to sell yet more, there was an emerging coalition of Italian designers and architects whose ambition it was to leave Modernism behind and to forge a new experimental era. The various individuals, groups and activities of the Italian Radical Design and Anti-Design movements operated from 1967 until the late 1970s/early 1980s.27 Well-known Radical Design groups such as Archizoom, Superstudio and Gruppo Strum critiqued the rationalist approach and contested design’s role in consumerism. A counter-architecture and design group Global Tools, 1974–1975, explored non-industrial techniques, inspired by the Arte Povera movement in Italy. In the mid-1970s, expressions of Anti-Design, from the likes of Studio Alchimia, led by Alessandro Mendini, revitalized design with an overt political, fun and deconstructionist message. There is no doubt that these Italian movements, and especially the theorist practitioners Andrea Branzi, Riccardo Dalisi and Lapo Binazzi, prepared the ground for a healthy pluralism and the seedbed for the emergence of Postmodern thought. This celebration of cultural pluralism recognized the ecology of the human condition, something Rationalism and Functionalism had ignored at its peril. In doing so, design genuinely sought to improve relationships between objects, spaces, the built environment and human fulfilment. Sadly, the genuine efforts of these proto-Postmodernists were easily subverted by commercial exploitation. The Italian manufacturer Alessi SpA was a knowing contributor to the debate, hiring early Postmodern luminaries such as the US architect and designer Michael Graves to create cutting-edge design for the cognoscenti, but their objectives were primarily driven by a commercial expediency. Questions of greater import around the deleterious effects of mass consumption on society and the environment were left to an emergent group of Postmodern ecologists and ‘alternative’ designers.

Out of the early Postmodern debate did emerge a genuine desire to involve people in the realization of design projects. An exemplar of this more participatory approach is the Byker Wall Estate in Newcastle-upon-Tyne by the architect Ralph Erskine with the local community (1973–1978). Yet it was the ecological imperative, rather than the social one, that garnered more attention during the 1970s.

The Postmodern ecologists

As the photographs from the Apollo space missions in the 1960s first revealed the beauty and fragility of planet Earth and Buckminster Fuller coined the expression ‘Spaceship Earth’, the environmental movement found new momentum. Buckminster Fuller was an early advocate of resource conservation throughout the 1960s. In 1963 he proposed an inventory of world resources,28 but it was 20 years later just before his death in 1983 that the likes of the World Resources Institute and other organizations took up the call in earnest. However, the social turbulence of the 1960s and new energy in the environmental movement stirred the global design community.

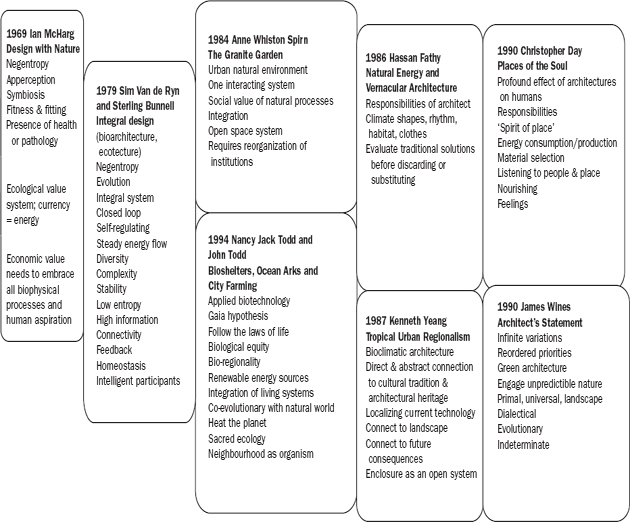

The manifestos and ambitions of the Postmodern ecologists are clearly expounded by Jencks and Kropf29 with Ian McHarg setting the foundation stone for this school of thought in his 1969 treatise, Design with Nature,30 firmly stating that the values of the economic system must embrace biophysical realities and human aspirations. The economy sits within a greater ecology, biotic and human, and to ignore that is perilous. It had taken two decades to synthesize the underlying concerns of Vogt, Leopold, Neutra, Packard and early environmentalist/scientists such as Rachel Carson (and her shocking revelations about environmental damage in Silent Spring31 into formative propositions for the design community. And it took a further two decades to progress the cause of Postmodern ecology, the main tenets of which are explored in Figure 2.3a and Figure 2.3b. Advocacy varies from biocentric to humanist perspectives and some manage to combine both perspectives to encourage more symbiotic relationships between man and nature. Their voice is still growing and perhaps with more urgency today as issues such as climate change and ‘peak oil’ impact on architecture and the design of transportation and food production systems.

The alternative designers

Parallel to the development of a strong line of Postmodern ecological architectural praxis, other design disciplines contributed to a critique of mainstream design and culture in the 1960s and 1970s. They were inspired in part by the Situationists International, a self-appointed group of cultural critics, led by Guy Debord, famous for their distribution of graphics and posters in the May 1968 Paris riots. Their critique of the commercial appropriation of all aspects of everyday life, and the acquiescence of creative professionals in this appropriation, not only tapped into the Zeitgeist but confronted all those involved in design with some searching questions.

First Things First – manifesto for graphic designers

A challenge to graphic designers, and those responsible for advertising and early brand management activities, was originated by Ken Garland in 1964, when he published the First Things First manifesto.32 This manifesto stimulated much debate in the graphic design industry varying from a positive shift towards the search for creating new meaning and a wholesale rejection of the manifesto for being naïve and idealistic. This shift from profit-/self-/form-centred design to human-centred design was a big challenge to the graphic design community. The urgency of this call got lost in the euphoria of popular culture and pop design coupled with the economic turbulence of the 1970s. However, the legacy lives on in organizations like Adbusters who, with Garland’s approval, updated and published a revised version of the First Things First manifesto in 2000.33

Victor Papanek and Design for Need

In 1969, the same year that McHarg published Design with Nature aiming at architects and landscape architects, the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID) initiated some soul searching among industrial designers. ICSID held a conference in London entitled ‘Design, Society and the Future’ encouraging designers to consider the economic, social and moral consequences of their work. In 1971, Victor Papanek launched his polemical book, Design for the Real World, striking deep into the design profession.34 Papanek’s pitch was straightforward – designers needed to take responsible decisions, spend less time designing ephemeral goods for the consumer economy, and spend more creative time on generating solutions to the real needs of the disadvantaged 80 per cent population of the planet. He was lauded and rejected in equal measure across the design world. Just a few years later, the Middle East oil price rise crisis in 1973–1974 gave another jolt to collective design thought. It even heralded the introduction of life cycle thinking (LCT) and life cycle analysis (LCA) by US design engineers challenged by the political administration to quickly find ways of becoming more energy efficient. In 1976, the Royal College of Art set up an exhibition and symposium called ‘Design for Need’ with Papanek as keynote speaker. This debate prompted the emergence of fresh design approaches – universal design, inclusive design and user-centred design, setting a lasting impact on design culture. However, this call to arms left the general modus operandi for industry unaffected.

Figure 2.3a

Design themes from Postmodern ecology

Alternative, appropriate and DIY technology

A mish-mash of ‘alternative design’ groups aspired to a simpler life, downshifting from the consumerist society and its multiplicity of negative impacts. Communities sprung up all over the world, reaching out for Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, a toolbox of ideas and equipment, to create an autonomous way of life.35 Some of these initiatives still flourish today, although they have all had to find some common ground to maintain relevance to mainstream culture. Examples include the Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales; Paolo Solari’s Arcosanti, an evolving town in the Arizona desert, US; and various eco-villages including Findhorn, Scotland. Second- generation experiments for alternative holistic design include sophisticated ecological community planning such as the Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems’ Advanced Green Building Demonstration in Austin, Texas, US, 1994–1997 and the Laredo Demonstration Blueprint Farm in Laredo, Texas, US, 1997 onwards.36

Other trends were visible in product design. In Germany in 1974, Jochen Gros formed the group Des-in which experimented by designing using recycled materials and alternative production methods. These experiments had little effect on German industrial product design, locked into the functionalist and production aesthetic of the Ulm School of Design, but did raise the consciousness within the design community to wider responsibilities.

Figure 2.3b

A model of nourishment and well-being in the new Postmodern eco-economic landscape

Yet another branch of this alternative design thinking were the ‘alternative’ or ‘appropriate’ technology groups who focused on issues of shelter, sanitation and potable water for poor communities in the North and South. The Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales37 was set up in 1973 by Gerard Morgan-Grenville and continues to to provide support, advice and training for those interested in everything from off-the-grid living to permaculture studies. The Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG) was founded in the UK in 1966 by E. F. Schumacher, author of Small is Beautiful, a seminal book on the value of locally focused economies.38 The ITDG still encourages design engineers to find practical, affordable solutions – a direct and lasting response to the call made by Schumacher and Papanek – and a vocation recently celebrated by the Cooper- Hewitt Museum in New York in its exhibition ‘Design for the Other 90%’.39

Out of this diverse range of alternative movements came the advocates of a particular form of ecological design – permaculture design – a holistic, minimal, interventionalist and ecological design approach. The founders of permaculture design were Bill Mollison and David Holmgren in the mid-1970s.40 They have continued to refine and develop the design principles over the past 30 years41 with emphasis on three underlying ethical principles – care of the Earth, its people and a fair share for everyone. Since 2002, permaculture thinking and practice has stimulated new forms of grassroots localization, like the Transition Towns movement aiming to ‘power down’ in response to the double whammy of climate change and peak oil.42

The eco-efficiency activists

From the early to mid-1980s, designers from a wide range of disciplines examined how they could aspire to create more eco-efficient buildings, products and services. This repositioning of their design philosophy sets them in a positive activist mould whose aim is to reduce the environmental footprint and impact of their creations. Quite simply, they adopted a new client – the environment.

Architectural responses tended to follow certain strategies: an update of vernacular traditions and techniques with sensitive culturally relevant design; reuse and recycling of materials; embedding of the latest eco-technologies to reduce a building’s environmental load. Occasionally the strategies were hybridized. This work is well documented in architectural publications and will not be further considered in detail (see examples cited pp17–18 and Note 39 on p29). There are rarer examples where ideas of socio-cultural sustainability are blended seamlessly with eco-efficiency and a powerful design aesthetic. The Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center, 1992–1998, in Nouméa, New Caledonia by the architect Renzo Piano, is an exemplar.

In the late 1980s there was a shift in Western European countries towards a concept of the ‘green consumer’.43 John Elkington penned a ten-point code for green designers for the Design Council in the UK in 1986. This galvanized certain sections of the industrial product design community, especially design engineers, who were helping companies to bring ‘green design’ products to the market.44 Through the early 1990s this approach to product design acquired the catch-all description of ‘design for the environment’ (DfE) and a well-developed toolbox emerged.45 DfE, also referred to as ‘eco-design’, was seen as a promising approach to encourage companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the Netherlands to improve their environmental standards, and to stimulate the debate among designers.46 Van Hinte and Bakker47 flagged the potential of design to communicate potential eco-design futures by proactive interventions, provocations, experimental prototypes (one-offs) and propositional or protest artefacts (see pp83, 85 for definitions). Their curatorial observations signalled a fresh avenue for exploration that was already being exploited by an exciting group of Dutch designers, Droog Design48 concerned with ecological, social, psychological and behavioural aspects of sustainability.

What are the Lessons Learnt?

This short perambulation of 19th- and 20th-century design history (see Chapter 4 for post-2000 design activism) sheds some illumination on the various expressions of design and whether they held any activist intentions. This canon of design history often reveals an inwardly focused design culture examining the self, egoism, the design community and its culture, rather than being orientated towards more altruistic ambition for specifically defined social, ethnographic or global causes. In general, designers seem to have been driven by personal and/or avant-garde ambitions although some of the mavericks and activists described above did counter design’s tendency for navel gazing. They were, however, few in number until the emergence of the consumer economies that rose out of the ashes of World War II. This seemed to release design from the pre-war constraints of Modernism, Functionalism and Rationalism. The euphoria of the economic miracles of the 1950s, and purposeful positioning of ‘Good Design’ (UK), ‘Bel Design’ (Italy) and ‘Good Form’ (Germany) by governments and their design bodies, was rudely supplanted by radical alternative design movements and popular consumer design in the 1960s. Concurrently, the reality of the downsides of the consumer economy began to bite as the extent of global environmental problems, coupled with the mid-1970s oil crisis and the general waning of European manufacturing, were felt. During the 1970s, some designers realigned themselves towards more altruistic purposes, but a paradigm shift in design philosophy was not to be realized (and we are still waiting). Some 30 years later, at the turn of the millennium, the majority of product, lighting and furniture designers were still largely untouched by more altruistic concerns connected with environmental and/or social issues.49

The target audiences for many of the design movements, groups and individuals cited above were predominantly aimed at designers, with a view to changing the way they think, approach their work and deliver their form-giving, rather than at specific targets external to the world of design. This implies a clear focus on changing design culture in research, education and practice. While difficult to quantify, the reality of effecting change in wider cultural settings often appears to have had a negligible, notional or rather diffuse impact at the social level. The main beneficiaries were often the designers themselves, the evolution of design culture and the growth of industrial and commercial enterprises. There are some notable exceptions, from the Deutscher Werkbund, and Hannes Meyer’s Bauhaus in Dessau, to the Design for Need movement of the 1960s and the work of individual luminaries in the 1970s, including architect Ralph Erskine, and some of the more socially conscious alternative design movements from the 1970s to the present day.

Design evolved and was generally synergistic with the growth of the Industrial Revolution, the ambitions of the Machine Age, Functionalism and the Modern movement. Design indulged in its own Postmodern fiesta, fetishizing over form (arguably this continues apace) and has bounced around consuming a plethora of short-lived ideologies for the past 40 years. Alain Findeli50 neatly summarizes a century and a half of these design cycles as a preoccupation with the rhetorical tools of aesthetics (late 19th/early 20th century), ergonomics (mid-20th century) and semiotics, which he notes is really ‘aesthetics again’ (in the late 20th century). While the heroes and heroines charting counter-narratives to the accepted design paradigm are few, they reveal a valuable lesson to aspiring design activists today – be very clear about your intentions, specify the target of your ambitions, and measure the results to ensure that the beneficiaries really do benefit.

By focusing on environmental positives, rather than socio-cultural ones, the story of design history looks somewhat different. While the British Arts and Crafts movement raised the spectre of massive environmental damage wrought by the Industrial Revolution, its impact in addressing it was minimal, although as a design phenomenon it was seminal in the evolution and reform of design culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After almost 70 years of very little environmental focus by designers there was a flurry of ‘alternative design’ champions in the 1970s, but the positive impacts were marginal and soon faded. A steady, but minority, uptake of Postmodern ecology practice since the late 1970s/early 1980s and the application of DfE since the mid-1980s has made progress and elicited a quiet design activism of its own, but remains a ‘minority sport’. An additional challenge is that eco-efficiency in buildings, services and products will not, in itself, guarantee future sustainability because of the well-documented ‘rebound effect’ where people spend the money released by eco-efficient goods or services on other things, and so negating any gains, or where the sales of eco-efficient products actually increase to deliver more overall environmental impacts. The eco-efficiency and eco-tech agenda will not alone rescind the likely repercussions of 150 years of economic growth. Significant shifts in individual and collective behaviour are required in combination with eco-effective design.

There is a growing need for new design heroes and heroines to provide some guidance to meet the enormity of the scale of the environmental, social and economic crises in the global, and regional/local, economies (see Chapter 3). While there have been, and are, some lucid voices from the design community,51 and the aforementioned maverick designers and architects, the silence from wider design education and practice communities is notable. Ironically, while design is acknowledged as a powerful communicative force, it has failed to communicate its own social and environmental ambitions to society, and so remains perceived as merely a servant to powerful economic imperatives. At the end of the millennium, Rachel Cooper’s rhetorical question, ‘Is design in a philosophical crisis?’, seems apt and timely.52 Perhaps sustainability offers the opportunity for design to find its real voice. It appears that design activists may have to multi-task by focusing on saving society, the environment and the future of design.

Notes

1 Julier, G. (2008) The Culture of Design, 2nd edn, Sage Publications, London, pp3–6.

2 The reference ‘North’ refers to the developed, Westernized countries largely found in the Northern hemisphere; the ‘South’ refers to the developing or emerging countries largely found in the Southern hemisphere. The design theorist and critic Guy Bonsiepe prefers use of the word ‘peripheral’ countries to describe the ‘South’ because it identifies ‘the core cause of under-development, which is the lack of autonomy to act’. The ‘central’ countries represents the North, which exercises tremendous power and control over the periphery. Bonsiepe, G. (1999) Interface, An Approach to Design, Jan van Eyck Academie, Maastricht, p100.

3 Hauffe, T. (1998) Design: A Concise History, Lawrence King, London, p10.

4 Sparke, P. (1987) Design in Context, Guild Publishing, London.

5 Julier (2008), op. cit. Note 1, pp3–11.

6 Sparke (1987), op. cit. Note 4, p8.

7 Jencks, C. and Kropf, K. (eds) (1997) Theories and Manifestoes of Contemporary Architecture, Wiley-Academy, Chichester; Murray, W. (2000) Brand Storm: A Tale of Passion, Betrayal, and Revenge, Financial Times/Prentice Hall, London.

8 Jencks, C. (1986) What is Post-Modernism?, Academy Editions, London.

9 Findeli, A. (2001) ‘Rethinking design education for the 21st century: Theoretical, methodological, and ethical discussion’, Design Issues, vol 17, no 1, MIT, Cambridge, MA, pp5–17.

10 See the trilogy of books that charts the design history from 1750 to 1990, from the Industrial Revolution to Postmodernity: Ponte, A. (ed) (1990) 1750–1850 The Age of the Industrial Revolution; Ausenda, R. and Ponte, A. (eds) (1990) The Great Emporium of the World; and Ausenda, R. (1991) The Dominion of Design, all published by Electra, Milan.

11 Richard Johnson’s ‘circuit of production and consumption’ and Paul du Gay’s ‘circuit of culture’ quoted in Julier (2008), op. cit. Note 1, pp66–69.

12 Wood, J. (2003) ‘The wisdom of nature = the nature of wisdom. Could design bring human society closer to an attainable form of utopia?’, paper presented at the 5th European Design Academy conference, ‘Design Wisdom’, Barcelona, April, available at www.ub.edu/5ead/PDF/8/Wood.pdf, accessed September 2008.

13 Fry, T. and Hart, A. (1999) A New Design Philosophy: An Introduction to Defuturing, New South Wales University Press, Sydney.

14 Fry, T. (2008) Design Futuring: Sustainability, Ethics and New Practice, Berg Publishers, Oxford; Willis, A.-M. (2008) ‘Design, redirective practice and sustainment’, keynote talk at 360 Degrees, a conference organized by the School of Architecture and Design, University of Brighton, UK, 19–20 September, on behalf of the DEEDS project, www.deedsproject.org.

15 Wahl, D. C. and Baxter, S. (2008) ‘The designer’s role in facilitating sustainable solutions’, Design Issues, vol 24, no 2, pp72–83.

16 Ponte (1990), op. cit. Note 10.

17 Ausenda and Ponte (1990), op. cit. Note 10.

18 Ibid.

19 Erlhoff, M. (2008) ‘Modernity’, in Erlhoff, M. and Marshall, T. (eds) Design Dictionary, Birkhaüser Verlag, Basel/Boston/Berlin, pp262–266.

20 Eisele, P. (2008) ‘Bauhaus’, in Erlhoff, M. and Marshall, T. (eds) Design Dictionary, Birkhaüser Verlag, Basel/Boston/Berlin, p41.

21 Bauhaus Archiv and M. Droste (1998) Bauhaus 1919–1933, Taschen, Köln.

22 Leopold, A. (1968) A Sand County Almanac, Oxford University Press, Oxford (first published 1949).

23 Neutra, R. (1954) Survival through Design, Oxford University Press, Oxford; and Vance Packard’s trilogy – The Hidden Persuaders (1957) and The Status Seekers (1959) both published by Penguin Books, Harmondsworth; and The Waste Makers (1960) David McKay Co, London.

24 Richard Hamilton cited by Whiteley, N. (1993) Design for Society, Reaktion Books, London, p167.

25 Sparke (1987), op. cit. Note 4, p214.

26 Sparke (1987), op. cit. Note 4, p217.

27 Fiell, C. and Fiell, P. (1999) Design of the 20th Century, Taschen, Köln, pp39–41, pp589–590.

28 Who is Buckminster Fuller?, http://www.bfi.org/our_programs/who_is_buckminster_fuller/design_science/design_science_decade

29 Jencks and Kropf (1997), op. cit. Note 7, pp133–168.

30 McHarg, I. (1992) Design with Nature, John Wiley & Sons, New York (first published by the Natural History Press, 1969).

31 Carson, R. (1962) Silent Spring, Hamish Hamilton, London.

32 Reproduction of the original First Things First manifesto by Ken Garland in 1964, www.xs4all.nl/~maxb/ftf1964.htm

33 Revised First Things First manifesto published by Adbusters in 2000, www.xs4all.nl/~maxb/ftf2000.htm

34 Papanek, V. (1974) Design for the Real World, Paladin, St Albans, originally published in 1972 in the UK by Thames & Hudson, London, written in 1971.

35 The story of Stewart Brand’s counterculture education and tools, that were made available via publications and educational tours, is outlined in Wikipedia’s article ‘Whole Earth Catalog’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whole_Earth_Catalog, accessed September 2008.

36 Wines, J. (2000) Green Architecture, Taschen, Koln, pp152–155.

37 Centre for Alternative Technology, www.cat.org.uk/information/aboutcatx.tmpl? init=4

38 Intermediate Technology Development Group, http://practicalaction.org/? id=about_us; and, Schumacher, E. F. (1973) Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered, Harper & Row, London.

39 Cooper-Hewitt National Museum, http://other90.cooperhewitt.org/; and Smith, C. (2008) Design for the Other 90%, Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York.

40 Mollison, B. and Holmgren, D. (1979) Permaculture One, Tagari Publications, Australia; Mollison, B. (1979) Permaculture Two, Institute of Permaculture, Australia.

41 Mollison, B. and Slay, R. M. (1997) Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual, Tagari Publications, Australia; Holmgren, D. (2002) Permaculture: Principles and Pathways beyond Sustainabilty, Holmgren Design Press, Australia.

42 Hopkins, R. (2008) The Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience, Green Books, Dartington, Totnes; see also Transition Towns, www.transitiontowns.org

43 Elkington, J. and Hailes, J. (1988) The Green Consumer Guide, Victor Gollanscz, London.

44 Mackenzie, D. (1991) Green Design, Lawrence King, London.

45 See for example, Lewis, H. and Gertsakis, J. (2001) Design + Environment, Greenleaf Publishing, Sheffield; Tischner, U. (2001) ‘Tools for ecodesign and sustainable product design’, in M. Charter and U. Tischner (eds) Sustainable Solutions, Greenleaf Publishing, Sheffield, pp263–281.

46 Van Hemel, C. G. and Brezet, J. C. (1997) Ecodesign: A Promising Approach to Sustainable Production and Consumption, United Nations Environment Programme, UNEP, Paris.

47 Van Hinte, E. and C. Bakker (1999) Trespassers: Inspirations for Eco-efficient Design, Netherlands Design Institute and 010 Publishers, Rotterdam.

48 Bakker, G. and Raemekers, R. (1998) Droog Design: Spirit of the Nineties, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam.

49 See for example the personal statements of 100 ‘iconic’ designers in Fiell, C. and Fiell, P. (2003) Design for the 21st Century, Taschen, Köln, where only 5 per cent of designers referenced both social and environmental concerns, and only a minority clearly felt that environmental concerns were a focal point their daily work.

50 Findeli (2001), op. cit. Note 9, p15.

51 For example, the writings and voices of Ezio Manzini, Stuart Walker, Guy Bonsiepe, Klaus Krippendorf, Victor Margolin, Richard Buchanan, Tony Fry and John Thackara.

52 Cooper, R. (2002) ‘Design: Not just a pretty face’, The Design Journal, vol 5, no 2, p1.