CHAPTER ONE

Managing Banking and Financial Services—Current Issues and Future Challenges

CHAPTER STRUCTURE

Section II Change is in the air-is the financial system being revolutionised?

Section III The Global Financial system-After the financial crisis

Section IV The Indian Financial System—An Overview

Section V The Indian Banking System—An Overview

KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM THE CHAPTER

- Understand the present state of the global financial system and the disruptive changes.

- Understand the basic causes behind the global financial crisis of 2007.

- Learn how macro economic factors can affect financial stability.

- Learn how financial stability can be achieved through better regulation.

- Understand how the Indian financial system is organized.

- Understand the various types and characteristics of financial markets.

- Learn about the evolution of the Indian financial system.

- Understand the impact of the financial sector reforms.

- Take a look at the future challenges in the global and Indian financial systems.

SECTION I

THE SETTING

It is no exaggeration to say that we are in the midst of a defining moment for innovation in financial services. Some expect that new technology will cause a complete disruption of traditional financial institutions, giving businesses and households access to more convenient and customized services. Entrepreneurs are also finding applications well beyond finance, and these new technologies could transform other fields, such as humanitarian aid

Remarks by Ms Carolyn Wilkins, Senior Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada, at Payments Canada, Calgary, Alberta, 17 June 2016. (accessed at www.bis.org)

Digital currencies, and especially those which have an embedded decentralised payment mechanism based on the use of a distributed ledger, are an innovation that could have a range of impacts on various aspects of financial markets and the wider economy. These impacts could include potential disruption to business models and systems, as well as facilitating new economic interactions and linkages

Introductory paragraph to the report by Committee on Payments and Market infrastructures, titled “Digital currencies”, published by the Bank for International Settlements in November 2015, accessed at www.bis.org

Financial institutions are increasingly at risk of losing business to fintech innovators, with 67 per cent already feeling the heat, says a PwC study.

News article, The Economic times, dated 7thapril 2017, accessed http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/banking/financialinstitutionsfeelingfintechheatsayspwcstudy/printarticle/58325723.cms

Banks should be monitoring innovations from five types of players: business-model disruptors, process innovators, technology start-ups outside the financial sector, digital banks, and platform attackers from other industries, such as e-tailing. Some of these innovations might radically reinvent banking; many can improve how banks currently do business.

Gergely Bacso, Miklos Dietz, and Miklos Radnai, “Decoding financial-technology innovation,” Mckinsey Quarterly, June 2015

In order to make more informed financial decisions, investors, lenders, and insurance underwriters need to understand how climate-related risks and opportunities are likely to impact an organization’s future financial position as reflected in its income statement, cash flow statement, and balance sheet…….

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, Final report “Recommendations of the Task Force Climate-related Financial Disclosures”, delivered at the G20 Hamburg Summit in July 2017, page 8

Welcome to the new future of Banking……

SECTION II

CHANGE IS IN THE AIR….IS THE FINANCIAL SySTEM BEING REVoLUTIoNISED?

Fintech1

Fintech is the term used to refer to technological innovations in financial services. It has been creating a lot of excitement – going by searches on Google – that have been reported to have soared more than 30 times in the last half decade!

In many cases, financial innovations are seen to be interesting twists on existing technologies and business models. They promise to lower costs, improve services and broaden access. Peer-to-peer lending is one example (Please refer to Chapter 6 for details). As the world has already seen with the taxi and hotel industries, peer-topeer services challenge traditional intermediaries.

This new paradigm may change the fundamental relationship existing financial institutions enjoy with their customers. Present regulations may need to tackle issues relating to consumer protection, market integrity, money laundering and terrorism financing, and their implications for financial stability.

Completely new technologies such as the Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) have the potential to replace entire transaction systems, including core payment systems. New products are being offered in the form of smart contracts – agreements in computer code that do not need human intervention to be executed.

In this new technological environment, regulators could face issues related to governance, legal environments and financial stability as well.

Digital currencies2

Money – the traditional understanding

Money denominated in a particular currency (money in a traditional sense) includes money in a physical format (notes and coins, usually with legal tender status) and different types of electronic representations of money, such as central bank money (deposits in the central bank that can be used for payments) or commercial bank money

E money

Electronic money (e-money) is value stored electronically in a device such as a chip card or a hard drive in a personal computer and is also commonly used around the world. Some countries have developed specific legislation regulating e-money

Digital currency

Hundreds of digital currency schemes based on distributed ledgers (see above) currently exist, are in development or have been introduced and have subsequently disappeared. These schemes share several key features, which distinguish them from traditional e-money schemes.

Assets – such as Bitcoins (see below – The Bitcoin phenomenon)

They have some monetary characteristics, such as being used as a payment mechanism

- They are not connected to a sovereign currency

- They are not backed by any authority such as a central bank, and hence are not a liability of any authority (see Chapter 2 for Central Bank operations)

- They derive value from the belief that they can be exchanged for other goods and services or a certain amount of sovereign currency at a later point in time. Hence they have zero intrinsic value

- The transfer of these currencies is through a built in distributed ledger. The mechanism allows remote peer-to-peer exchanges of electronic value in the absence of trust between the parties and without the need for intermediaries. Typically, a payer stores in a digital wallet his/her cryptographic keys that give him/her access to the value. The payer then uses these keys to initiate a transaction that transfers a specific amount of value to the payee. That transaction then goes through a confirmation process that validates the transaction and adds it to a unified ledger of which many copies are distributed across the peer-to-peer network.

- The institutions that are actively developing and operating these schemes are non banks

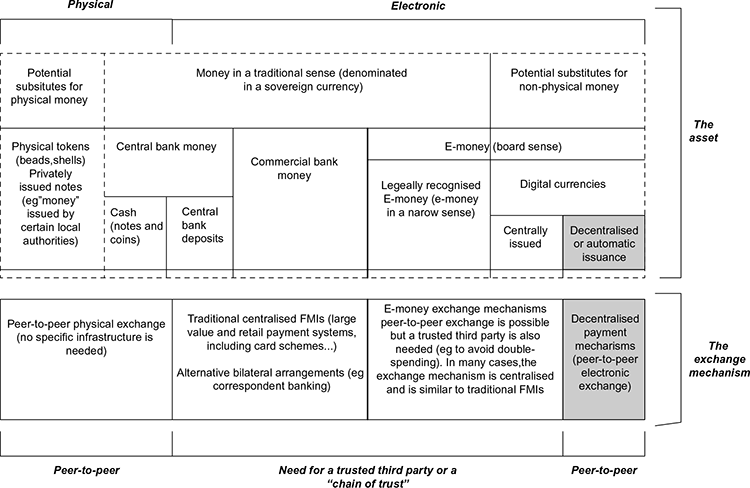

Figure 1.1 illustrates the separation between the two basic aspects of digital currency schemes (the asset side and the decentralised exchange mechanism based on a distributed ledger), and aims to provide a framework to help explain where e-money and digital currencies could be placed in relation to other types of money.

The Bitcoin phenomenon

The original concept paper behind Bitcoins, a decentralized electronic cash system using peer-to-peer networking to enable payments between individual parties was presented in 2008 by Satoshi Nakamoto in “Bitcoin: A peer to peer electronic cash system”.

Figure 1.2 shows how a typical Bitcoin transaction works

Climate change and financial system3

One of the most significant but most misunderstood, and underrated risks that the world and its organizations face today relates to climate change. To stem the disastrous effects of climate change, nearly 200 countries agreed in December 2015 to accelerate the transition to a low carbon economy. Since such a transition requires considerable and even disruptive changes across economic sectors, financial policy makers have been exploring the implications for the global financial system. The negative implications could include financial dislocations and sudden losses in asset values. Against this background, the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors asked the Financial Stability Board to review how the financial sector can take account of climate related issues.

FIGURE 1.1 FORMS OF MONEY AND EXCHANGE MECHANISMS

FIGURE 1.2 A BITCOIN TRANSACTION – THE STEPS

The Task Force set up for this purpose made its final recommendations in July 2017. These recommendations apply to financial sector organizations, including banks (lending activity), insurance companies (underwriting activity), asset managers (asset management such as Mutual funds) and asset owners (such as public and private sector pension plans, endowments and investment foundations).

The Task force has stated that the disclosures by the financial sector could foster an early assessment of climate related risks and opportunities, improve pricing of climate related risks, and lead to more informed capital allocation decisions.

The implementation plan spans a five year horizon reform.

SECTION III

THE GLoBAL FINANCIAL SySTEM – AFTER THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

It has been about a decade since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-08.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS), in its 87th Annual Report, 2016-17, (http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2017e.pdf) has looked back at satisfaction at the past one year, where the global economy has strengthened further. The salient points from the extensive discussions in the Annual Report are summarised in the following paragraphs.

The BIS report points out that growth has approached long-term averages, unemployment rates have fallen towards pre-crisis levels and inflation rates have edged closer to central bank objectives. It also looks to the near term future with optimism. However, the report examines four risks that could threaten the sustainability of the expansion in the medium term: a rise in inflation; financial stress as financial cycles mature; weaker consumption and investment, mainly under the weight of debt; and a rise in protectionism.

However, global response is vital in key areas –ranging from broad principles to common standards. The five key areas identified by BIS are: prudential standards, crisis management mechanisms, trade, taxation and monetary policy.

A first priority is to finalise the financial (prudential) reforms under way. Among the reforms, completing the agreement on minimum capital and liquidity standards – Basel III – is especially important, given the role banks play in the financial system. The task is to achieve agreement without, in the process, diluting the standards. There is ample empirical evidence indicating that stronger institutions can lend more and are better able to support the economy in difficult times. A sound international agreement, supported by additional measures at the national level, combined with the deployment of effective macroprudential frameworks, would also reduce the incentive to roll back financial integration. The Basel agreements are explained in detail Chapter 11 of this book.

A second priority is to ensure that adequate crisis management mechanisms are in place. Regardless of the strength of preventive measures, international financial stress cannot be ruled out. A critical element is the ability to provide liquidity to contain the propagation of strains. The intermediation of global currencies, especially the dollar, also creates close linkages between globally active banks. The Global Financial Crisis demonstrated how such interconnectedness propagated funding stress between the world’s largest banks and forced them to deleverage internationally. Thus, the regulatory reforms in the aftermath of the GFC have focused on strengthening the resilience of international banks that are the backbone of global financial intermediation. Liquidity risk management and its relationship with other risks is explained in Chapter 12 of this book

Another overarching priority would be to further the room for greater monetary policy cooperation that would help limit the disruptive build-up and unwinding of financial imbalances. A detailed explanation on Monetary Policy is contained in Chapter 2 of this book

The Annual Report also recognizes the increasing role of technology and non bank players in the management of banks globally.

Another paper from BIS4 categorizes financial crises into banking, currency and sovereign debt crises. Recent research shows that during the period 1970 – 2011, currency crises occurred most frequently (218), followed by banking crises (147) and sovereign debt crises (66).

Since the first quarter of 2010, sovereign debt tensions and their impact on banks and economies have dominated. Sovereign debt crises have been more pronounced in the euro area. How is sovereign risk related to the banking and currency crises? Box 1.1 explains.

BOX 1.1 THE BANKING CRISIS–SOVEREIGN CRISIS NEXUS EXPLAINED

The recent global financial crisis and the consequent deepening of the euro debt crisis clearly indicate the interdependencies between banks and sovereign risk. Several research studies have found a link between the fiscal and financial distress. Discussing the transmission channels during the fiscal and financial turmoil, Reinhart and Rogoff (2011) present a set of four stylized facts. First, private and public debt booms ahead of banking crises. Second, banking crises, both home-grown and imported, usually accompany or lead sovereign debt crises. Third, public borrowing increases sharply ahead of sovereign debt crises; moreover, it turns out that the government has additional ‘hidden debts’ (domestic public debt and contingent private debt). Fourth, the composition of debt shifts towards the short term before both debt and banking crises. Further, a default may take place if the financial crisis ignites a currency crash that impairs the sovereign’s ability to repay foreign currency debt.

The bailout of banks by their respective countries during the recent global financial crisis has led to a shift of credit risk from the financial sector to national governments and led to an increase in sovereign risk (Acharya, et al, 2010).

However, historically, the transmission of distress has often moved from sovereign to banks with sovereign defaults triggering bank crises (Caprio and Honahan 2008). The anaemic economic growth combined with high debt-to-GDP ratio has led to frequent downgrades of the sovereign ratings of euro area [Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain (GIIPS)] countries by credit rating agencies. With an increase in sovereign debt risk, banks were also affected as they were the major holders of sovereign bonds.

There are multiple channels through which the increase in sovereign risk feeds into the banks’ funding costs: (i) losses on holdings of government debt weaken banks’ balance sheets, increasing their riskiness and making funding more costly and difficult to obtain; (ii) higher sovereign risk reduces the value of the collateral which banks can use to raise wholesale funding and central bank liquidity; (iii) sovereign downgrades generally flow through to lower ratings for domestic banks, increasing their wholesale funding costs and potentially impairing their market access; and (iv) a weakening of the sovereign reduces the funding benefits that banks derive from implicit and explicit government guarantees (CGFS-BIS 2011).

The interdependency between the sovereign and their banks can be clearly seen for euro area GIIPS countries, as both sovereign and bank risk (largest bank in the respective country), as measured by CDS spreads, tend to move together during the crisis.

The sovereign and banking stress increased as investors’ concerns about the political situation in Greece and the implications of the difficulties experienced by the Spanish banking system were compounded by a perceived lack of cohesion among governments in upgrading the crisis management mechanisms in the euro area.

References

Acharya, Viral V, Drechsler, I and Schnabl, (2011), ‘A Pyrrhic Victory? Bank Bailouts and Sovereign Credit Risk’, NBER. Working Papers 17136, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Barth, James R, Apanard Prabha and Greg Yun, 2012, The Eurozone Financial Crisis: Role of Interdependencies between Bank and Sovereign Risk’, Journal of Financial Economic Policy, vol. 4.

Caprio, Gerard and Patrick Honahan 2008, ‘Banking Crisis’, Center for Development Economics, Williams College. CGFS-BIS, 2011, The Impact of Sovereign Credit Risk on Bank Funding Conditions, CGFS Papers No. 43, Bank for International Settlements.

Rogoff, Kenneth S and Carmen M. Reinhart, (2011), A Decade of Debt, NBER Working Paper 16827, National Bureau of Economic Research.

A Rewind to the Financial Crisis of 2007–08

No discourse on ‘banks’, and more so, ‘managing banks’, can begin without reference to the credit market turmoil of 2007. The global crisis spared no country—developed or developing. With many countries’ financial systems having grappled with the after-shocks of what began as a sub-prime lending crisis in the United States, it comes as no surprise that voluminous literature already exists on the causes of and lessons from the crisis, as well as remedial action taken by governments and regulators in various countries.

We will discuss the events that led to the crisis in detail elsewhere in this book. However, what is more important is the way forward. The financial system is the lifeline of any economy. It is therefore only natural that the ‘future’ of banking is hotly debated topic at not only banking forums but also at every congregation of professionals from various walks of life.

The term ‘paradigm shift’ is now being applied to banking as well. The question is—what does this ‘shift’ constitute? Will it mean jettisoning the old model of banking and adopting a completely new one? Or, would it signify fine tuning existing banking practices so that ‘crisis management’ is strengthened through effective anticipation and preventive action?

The Causes of the Crisis

Several arguments/theories/events have been cited as the causes of the 2007 crisis. But, there seems to be consensus on one possible over arching cause—lack of adequate attention from monetary authorities and regulators to certain factors that were shaping the global financial system when the crisis happened. Three groups of mutually reinforcing factors were then contributing to increased ‘systemic’ risk. They were as follows:

- Lower interest rates caused by worldwide macroeconomic imbalances over the last decade, inducing heightened risk taking and contributing to extremely high asset prices—the asset price ‘bubble’.

- Changing structure of the financial sector and rapid pace of financial innovation over the last two decades, and the failure of ‘risk management’ to match up to the new demands.

- Failure to adequately regulate highly leveraged financial institutions.

Prevalent models of banking

The aftermath of the global financial crisis ushered in the consequent need for a fresh assessment of the financial and banking sectors, including institutional and regulatory structures. In addition, changes in regulatory requirements and approach envisaged by Basel III, requiring increased analytic and risk assessment capacity in banks, necessitated a fresh look at the desired and optimal contours of a dynamic banking sector

The broad functions and objectives of the banking structure are more or less similar across countries. However, globally, there are different models of banking structures, different ownership patterns, and different emphasis on size of the banks. Country-level studies show that small, regional and local banks may perform very differently from large banks

The theoretical debate on how much banks and the financial system should be regulated is voluminous and continuing. However, the necessity of regulating the financial system and banks in particular is universally accepted on financial stability and consumer protection concerns. In fact from the lessons of the current crisis, the regulatory and accounting framework for banks has become more stringent, as we would learn in subsequent chapters.

Investment banks, Commercial banks and Universal banks – what is the difference?

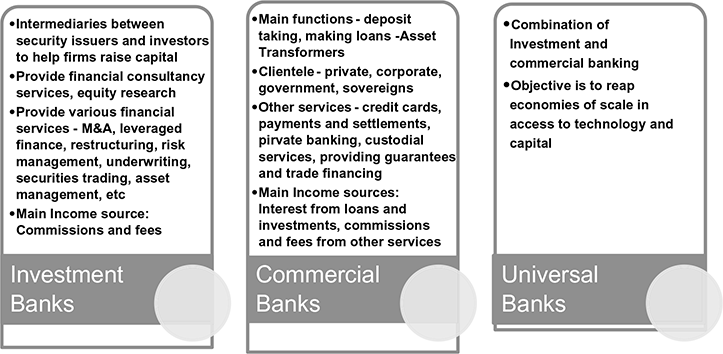

There are basically two pure models of banking: commercial banking and investment banking. Universal banking represents a combination of the two banking models in varying proportions. Thus there are commercial banking oriented Universal banks (Bank of America, Citi Group, HSBC, etc.) and Investment banking oriented Universal banks (Barclays, BNP Paribas, UBS, Deutsche Bank.)

Figure 1.3 makes a comparison between Investment Banks, Commercial Banks and Universal Banks

FIGURE 1.3 INVESTMENT BANKS, COMMERCIAL BANKS AND UNIVERSAL BANKS- A COMPARISON

With the demise of investment banks in the wake of the crisis, the universal banking model remains the dominant model. However the model is not without its risks. The potential systemic risks of the model is being addressed by the Basel III framework through enhanced regulatory framework, pro-active and intensive supervision and efficient resolution framework, enhanced transparency and disclosure and strengthened market infrastructure. In addition, there are proposals for structural reforms – Dodd-Frank Act (under implementation in USA), proposals in Vickers Report (UK) and Liikanen Report (Euro zone) – under consideration for implementation. These regulatory frameworks are discussed in later chapters

Macroeconomic and Financial Stability—Understanding the Linkages

Studies of economic cycles show that ‘booms’ and ‘busts’ are typical of market-driven systems. ‘Depressions’, ‘recessions’ and ‘market crashes’ have all happened and passed into history, leaving behind painful memories, case studies and vital practical lessons to be learnt.

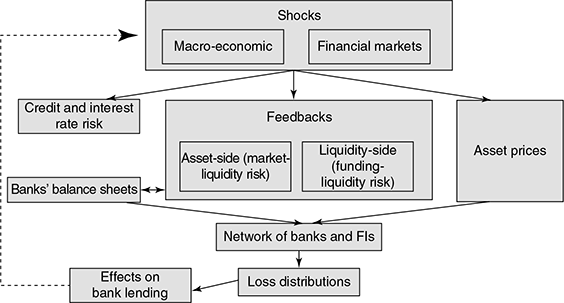

How are a country’s macroeconomic developments and financial stability related? Figure 1.45 depicts the linkages between shocks in the real sectors of the economy and the financial sector.

Let us understand the figure using the example of the global crisis of 2007. The shock to the US economy began as an asset bubble in the real estate (housing) sector, caused by banks lending to sub-prime (less than creditworthy) borrowers.6 The delinquency of such borrowers led to credit and interest rate risk7 for banks involved in the lending. Since many of these banks, by this time, had ‘securitized’ the loans8 and transferred the risks to other banks/entities, and the underlying asset prices had fallen drastically, liquidity in the market dried up. Funding available in the market also dwindled, partly because there was no liquidity and, also due to banks being wary of lending to other borrowers/banks which needed funding.9 The high degree of interlinkages in the various markets led to a rapid transmission of the crisis from one segment to other segments. Ultimately, many banks ‘and other institutions’ balance sheets10 were affected. Taken together, the combined effect of various risks reflected in the aggregate loss distribution, which can be mapped back to the adverse impact on bank lending and the economy. In this case, since several banks and other institutions around the world were involved as ‘buyers’ or ‘insurers’ or ‘traders’ of credit risk, a number of other countries’ financial systems were adversely affected. Hence, the United States sub-prime mortgage market triggered a credit market crisis at the global level, the depth of whose adverse effects are being estimated even in 2009–2010.

FIGURE 1.4 INTERRELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN MACROECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS AND FINANCIAL STABILITY

How do we define ‘financial stability’? There is no single definition for financial stability (and the term ‘systemic risk’ which is used in tandem). Hence, the term takes on contextual meaning, signifying smooth functioning of the financial system, both under normal and stressed conditions.11

The recent credit crisis, like others before it, has thrown up several issues and challenges for banks and other financial institutions, as well as central banks and regulators. However, all stakeholders agree on one thing—recovery of the global financial system depends on restoration of ‘TRUST’.

The Role of ‘Trust’ in Financial Stability

The global crisis witnessed the crumbling of the very foundation of a sound financial system—TRUST.

There was a ‘massive breakdown of trust across the entire financial system—trust in banks and non banks, trust in central banks and other regulators, trust in credit rating agencies, trust in investment advisors, trust in brokers, dealers and traders, and trust in the financial markets, if not in the market system itself’.12

The loss of trust, coupled with failure of banking behemoths and lack of transparency, led to great fear and uncertainty. Which were the banks/institutions that could withstand losses? Can the potential losses be estimated with certainty? Were there lurking risks in the system that could explode in the future? Frightening questions—with no reassuring answers—resulted in unprecedented panic. Banks that had liquidity, hoarded it. Banks that did not have liquidity faced doomsday, since they got no help from the distrusting markets. The financial markets nearly went into a deep freeze. Long-standing financial institutions that had appeared rock solid quietly folded up. Lack of trust had almost brought the entire chain of financial intermediation to a standstill.

The Role of Regulation in Ensuring Financial Stability

The G20 Working Group on ‘enhancing sound regulation and strengthening transparency’ (Working Group I), in its report13 dated 25 March 2009, has reiterated the paramount importance of robust financial regulation in each country based on effective global standards for financial stability in future. The report has acknowledged the role of regulation as the first line of defence against financial instability. It sums up the cause of the financial crisis: ‘In hindsight, policy makers, regulators and supervisors in advanced countries did not act to stem excessive risk taking or to take into account the inter-connectedness of the activities of regulated and non-regulated institutions and markets’.

Experts have identified some of the areas that were given inadequate attention as the following:

- The ‘perimeter’ of regulation. In deciding which institutions and practices should be regulated and to what extent, the regulators had overlooked that some institutions outside their purview were taking on excessive risks, and that some of these risks were not ‘visible’ or ‘detectable’.

- Procyclical practices. Booms in the economy lead to higher confidence levels both among borrowers and lenders. As a consequence, lenders become lax about credit standards and borrowers turn overconfident about the potential of projects they invest in. When the economy is on the downturn, banks become wary and tighten lending standards and pull back liquidity.

- Information gaps about risk and where they were distributed in the financial system. This happened in the case of financially engineered products, where credit risk transfer was done in a distributed manner. Though the principle of ‘structuring’ was to transfer risk to those parties who could best bear them, the rapid increase in demand for such high-yielding products led to lower transparency. As a result, most sellers and the buyers of these products lacked adequate understanding of what they were selling or buying, thus exposing themselves to greater risks.

- Lack of cross-border information flow and co-operation among regulators in various countries. There was no harmonization of national regulatory policies and legal frameworks in various countries, even though risks were being transferred across countries.

- Provision of liquidity by regulators in the event of crisis.

It is, therefore, clear that the regulatory framework needs considerable strengthening. The stark lessons from the crisis will ensure that adequate regulation will be receiving significant attention in future.

The Objectives of Financial Regulation

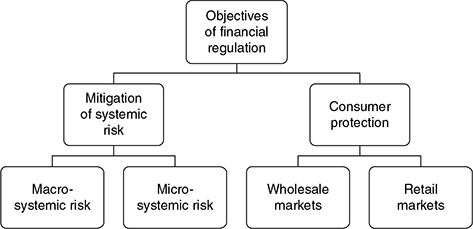

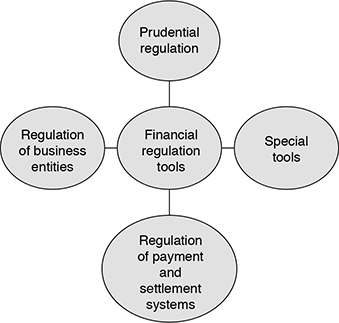

According to an IMF Working Paper,14 there are two vital objectives of financial regulation, as depicted in Figure 1.5.

We have already seen how the failure of financial institutions can have a wider impact on financial markets and macroeconomic stability. However, even a weak financial system can have adverse effects on economic growth and stability. Individual banks or financial institutions would not be able to assess the overall economic impact of bank level business decisions. Hence, regulation is used to mitigate such systemic risks.

As seen in Figure 1.5, systemic risks can be macro or micro in nature. Both types of risks, in essence, are interrelated.

When risks taken by various banks/institutions in the economy have a correlated negative impact across other institutions, the financial system as a whole gets weakened and economic growth is adversely affected. This is macro systemic risk, and the credit crisis of 2007 is an example of this risk.

In micro-systemic risk, the failure of one bank or institution has an adverse impact on the financial system as a whole. For example, failure of one bank can cause a loss of confidence and trigger a run on other banks, even those that are fundamentally sound.

How are the objectives of mitigating systemic risks and customer protection related and regulated? The following examples illustrate the facts:

- In financial markets, the sellers of financial products (say, deposit accounts or insurance services) have more information than the buyers (customers of banks, insurance, etc.). Hence, regulation is required to establish rules and procedures for disclosure of information or limit risk by placing a cap on the amount that can be invested in certain products.

- In retail markets, it is necessary for the regulator/regulation to ensure that the provider of financial services is in good financial health, since the payoff to the customers (e.g., repayment of deposits, insurance proceeds, and so on) is dependent on it.

- In wholesale markets, say in the case of securities, the sellers of securities have more information than the investors. Hence, more disclosures by way of information given in prospectuses or stiff penal clauses to restrain undesirable practices, such as insider trading are required. More transparency can be achieved through regulation.

FIGURE 1.5 OBJECTIVES OF FINANCIAL REGULATION

FIGURE 1.6 TOOLS OF FINANCIAL REGULATION

According to the IMF paper, quoted above, financial regulation can be done using four broad tools (see Figure 1.6). These are as follows:

- Prudential regulation typically sets out regulatory prescriptions for maintaining capital or liquidity or credit quality. The regulation seeks proactive remedial action.15

- Specialized tools in the hands of central banks and other regulators are the role of ‘lender of last resort’(LOLR) or deposit insurance.16

- Regulation of payment and settlement systems is vital for ensuring post-trade transactions in financial contracts are managed well.17

- Business regulation aims to regulate activities of financial market participants through regulation of trading activity and financial market products.18

Financial Stability—the Over-arching Agenda for the Future

One of the key lessons from the crisis is that financial stability does not automatically follow price stability or macroeconomic stability. In an increasingly globalizing world, a threat to financial stability in any country could trigger a series of responses that jeopardize the financial stability of other countries. Hence, ‘financial stability’ will, in future, have to be looked at as an explicit objective, rather than an implicit objective of economic policy and growth.

A lot of discussion has already taken place at the highest levels in international forums, and these discussions are forming the basis for new or altered regulation or supervisory guidance. Some of the significant actions already taken include strengthening the Basel 2 capital framework,19 developing global standards for liquidity risk management,20 strengthening supervision of cross-border financial conglomerates, reviewing international accounting standards,21 strengthening the functioning of credit rating agencies,22 rationalizing compensation structures and extending the scope of regulation to cover non-banking financial institutions.23 (See Box 1.2, for the role of non-banking financial institutions—also called ‘shadow banking system’ in the financial crisis.)

BOX 1.2 ROLE OF THE ‘SHADOW BANKING SYSTEM’ IN THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

Internationally, the non-banking financial institutions are also termed ‘other financial intermediaries’ (OFI). They typically include, among others, pension funds, securities dealers, investment funds, finance, leasing and factoring companies and asset management companies. They can also include the less understood special investment vehicles (SIVs), conduits, money market funds, monolines, investment banks, hedge funds and other non-banking financial services.24 Since many of these operations are opaque, these entities are sometimes categorized as part of a ‘shadow banking system’.

In the run up to the financial crisis of 2007, many of these shadow banks, which were typically bank subsidiaries or associates, capitalized on regulatory gaps. They raised short-term funds in the market, such as ‘commercial paper’ and invested in illiquid, long-term assets, such as sub-prime mortgages or other SIVs. The danger with this approach was that if the assets failed to return cash flows (from repayments and interest), the short-term borrowings could not be repaid. The shadow banks, being outside the banking system, did not have access to the ‘lender of last resort’ protection from the central banks. Thus, if the market turned illiquid, these entities could become insolvent.

Unfortunately, the worst scenario materialized. The sub-prime assets failed to return cash flows and the shadow banks scrambled for liquidity to refinance the short-term liabilities. The liquidity in the market too, soon dried up and many of these entities were forced to declare bankruptcy. The contagion spread to the parent banks as well, as the credit risk in sub-prime mortgages, and the market risk in structured products rapidly turned into a systemic liquidity risk. Since many international banks were involved in shadow banking activities, the US centred sub-prime crisis snowballed into a major global financial credit and liquidity crisis.

The Financial Stability Board (FSB)25, in April 2012, defined shadow banking system as ‘Credit intermediation involving entities and activities outside the regular banking system’.

At the Cannes Summit in November 2011, the G-20 leaders agreed to strengthen the oversight and regulation of the shadow banking system and endorsed the FSB’s initial recommendations with a work plan to their further development in the course of 2012. The FSB has adopted a two-pronged approach. First, the FSB will enhance the monitoring framework by continuing its annual monitoring exercise to assess global trends and risks, with more jurisdictions participating in the exercise. Second, the FSB will develop recommendations to strengthen the regulation of the shadow banking system, wherever necessary, to mitigate the potential systemic risks.

In April 2012, the FSB in its report on shadow banking system to the G-20 leaders reviewed the progress made.

Does India Have Shadow Banking System?

In India and certain other countries like Turkey, Indonesia, Argentina, Russia and Saudi Arabia, the non-banking financial assets remained below 20 per cent of GDP at the end of 2012. However, the sector showed rapid growth, though from a low base, in some of these jurisdictions, including India. In the Indian context, the Non-Banking Finance Companies (NBFCs) are regulated by the Reserve Bank and all types of Mutual Funds (MFs) are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). As such, India does not have shadow banking entities, in the formal financial system with potential for creating systemic instability. However, a large number of non-bank financial entities function in the unorganized sector (unincorporated entities outside the purview of regulatory perimeter), whose collective size and profile of activities need to be gauged to ensure that they do not pose any threat to the ‘trust’in and ‘stability’ of India’s financial system.

The encouraging signal emerging from global deliberations is the recognition that international co-operation is key to resolve crises of such proportion. The various working groups constituted by the G-20 have emphasized that future regulation and supervision must reinforce risk management capacity of financial institutions. Greater transparency and lower regulatory ‘arbitrage’ (defined later in this chapter) have also been insisted upon. A major outcome is the establishment of a new Financial Stability Board (FSB) to be operated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), with strengthened mandate that includes all large countries of the world.

The Global shadow banking monitoring report, 2016 (http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/global-shadow-banking-monitoring-report-2016.pdf) by the FSB throws up interesting trends. The report, covering 28 jurisdictions accounting for over 80% of global GDP, states that while banks continued to grow during 2015, their share in the financial system declined for the fourth consecutive year, particularly in the Euro area.

The ‘other financial intermediaries’ (OFI), that are comprised of all financial institutions that are not classified as banks, insurance corporations, pension funds, public financial institutions, central banks or financial auxiliaries, saw a growth in their assets equal to 150 % of total GDP of these countries at the end of 2015. The previous peak of 139% in this measure was observed prior to the financial crisis of 2007-08.

The report also mentions a Narrow measure of shadow banking (or the ‘narrow measure’ or ‘shadow banking under the economic functions approach’) that includes non-bank financial entity types that are considered by authorities to be involved in credit intermediation where financial stability risks from shadow banking may occur. This narrow measure, that is expected to financial stability risks, grew 3.2 % to $34 trillion in these countries, excluding China. The uncontrolled growth in shadow banking has serious implications for the economies and the banking systems.

SECTION IV

THE INDIAN FINANCIAL SYSTEM—AN OVERVIEw

Financial Stability in India

The financial system of any country has two important segments—the financial markets and the financial intermediaries.26

The turmoil in the global financial system has triggered introspection and discussion on the stability of the Indian financial system. Some have termed the fact that India has not faced any financial crisis so far as a consequence of deregulation as ‘remarkable’, while others attribute it to the ‘correctness of ‘judgement’ that reforms to global standards need to be adjusted to local conditions’.27 The relative insulation of India could also appear ‘fortuitous’, since the credit derivatives market is in an embryonic stage and the originate-to-distribute model in India is not comparable to that in developed markets, or ‘conservative’, since regulatory guidelines on securitization do not permit immediate profit recognition or the reforms were not speeded up through bold and drastic steps as in other countries.

However, the fact remains that the Indian financial sector has matured since the financial reforms were instituted. What we see today is a reasonably sophisticated and robust system delivering a diverse range of financial services, efficiently and profitably. With deregulation, the operational and functional autonomy of financial institutions has increased and, so has their participation in various financial market segments in the face of heightened international competition. It is also moving towards the goal of financial inclusion by accelerating growth momentum while containing risk and emphasizing on ‘financial stability’.

In order to understand the challenges and issues confronting, the Indian banking system in the present context, it is necessary to understand the structure and evolution of the Indian financial system.

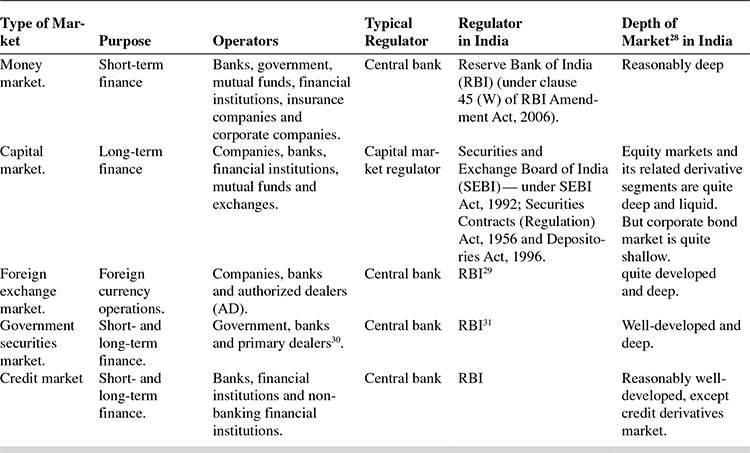

One way of understanding the financial market structure is to look at its components. Table 1.1 classifies financial markets into broad components and lists their typical characteristics. The table also indicates the broad aspects of regulation in each market, as well as the depth of the market in India.

TABLE 1.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF FINANCIAL MARKETS

Table 1.2 outlines the typical instruments, their salient features, and some of issues to be resolved in each market.

To summarize, Figure 1.7 depicts the manner in which the financial system is regulated at present.

FIGURE 1.7 REGULATORY STRUCTURE OF THE INDIAN FINANCIAL SYSTEM

SECTION V

THE INDIAN BANKING SYSTEM—AN OVERVIEW

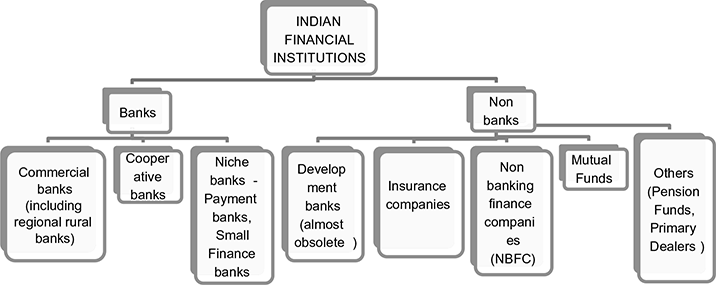

The key feature that distinguishes the Indian banking sector from the banking sectors in many other countries is the plethora of different types of institutions that cater to the divergent banking needs of various sectors of the economy.

For example, Credit cooperatives were created to cater to the credit, processing and marketing needs of small and marginal farmers organised on cooperative lines. These institutions later expanded in urban and semiurban areas in the form of urban cooperative banks to meet the banking and credit requirements of people with smaller means. Regional Rural Banks were created to bring together the positive features of credit cooperatives and commercial banks and specifically address credit needs of backward sections in rural areas. Local Area Banks were brought in to bridge the gap in credit availability and strengthen the institutional credit framework in the rural and semi-urban areas.

Though the capital market size has expanded substantially since financial liberalization, the Indian financial system is dominated by financial intermediaries.37 The commercial banking sector holds the major share (about 60 per cent) of the total assets of the financial intermediaries, which comprise of commercial banks, urban co-operative banks, rural financial institutions, non-banking finance companies, housing finance companies, development financial institutions, mutual funds and the insurance sectors.

The financial institutional structure in India

The financial institutional structure in India can be broadly classified into: (a) commercial banks; (b) financial institutions; (c) non-banking finance companies; and (d) co-operative credit institutions. (See Figures 1.8 to 1.8G).

FIGURE 1.8 THE FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS STRUCTURE IN INDIA

FIGURE 1.8A THE COMMERCIAL BANKING SYSTEM

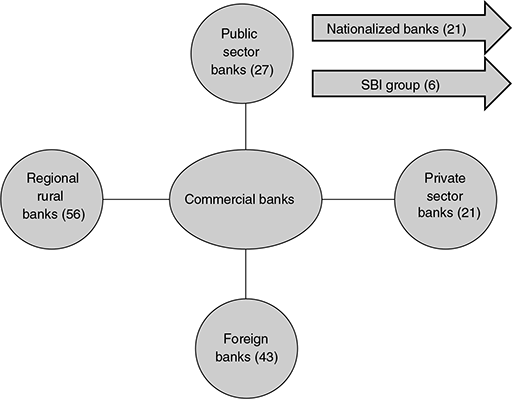

WHO OWNS THE COMMERCIAL BANKS IN INDIA?

Public Sector Banks

At the end of March 2016, there were 27 public sector banks in India, comprising of State Bank of India and its associate banks (6), and 21 nationalized banks.

The public sector banks in India are regulated by statutes of the Parliament and some important provisions under section 51 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949.

Specifically, the regulations are as follows:

- State Bank of India (SBI) regulated by the State Bank of India Act, 1955.

- Subsidiary banks of State Bank of India regulated by State Bank of India (Subsidiary Banks) Act, 1959. After the merger of SBI with its subsidiaries described below, these Acts would be amended suitably.

- Nationalized banks regulated by Banking companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Act, 1970 and 1980.

The statutes also stipulate that the central government is mandated to hold a minimum shareholding of 51 per cent in nationalized banks and 55 per cent in State Bank of India (SBI). In turn, SBI will have to hold a minimum 51 per cent of the shareholding in its subsidiaries. Another stipulation is that foreign investment in any form cannot exceed 20 per cent of the total paid up capital of the public sector banks.

Very shortly, SBI would complete the process of merger of five associate banks and Bharatiya Mahila Bank (BMB) with itself. Post merger, about 1500 branches of the combined entity would be closed. Once the merger is completed, SBI is expected to become a lender of global proportions, with an asset base of Rs 37 billion (over $555billion), and 22500 branches. SBI would figure in the list of top 50 banks globally, being ranked 45th. The Bill approving the amalgamation has been passed in the Indian parliament.

From 1984–1985, there have been three distinct ‘phases’ of equity infusion by the government into public sector banks. In the period up to 1992–1993, all nationalized banks were capitalized without any predetermined norm. Over the next couple of years, (up to 1993–1995), when the first phase of financial reforms were under way, some ‘weak’ nationalized banks were put on a recovery path and in the following years, the government, as owner, had to improve banks’ capital position to levels stipulated by the Basel Accords. In 2006–2007, banks were allowed to raise capital from the public through equity issues. The relevant Acts were amended to permit banks raise capital to a level not exceeding 49 per cent of their equity base.

The government is considering merging the nationalised banks to ultimately have about four large state run banks.

The Board of public sector banks comprises of whole time directors—chairman, managing director(s), executive directors, government nominee directors, RBI’s nominee directors, workmen and non workmen directors and other elected directors.

The Indian government has recently constituted the Banks Board Bureau (BBB) for selection of Managing Directors and Directors of public sector banks and financial institutions.

Private Sector Banks

At the end of March 2016, there were 21 private sector banks in India.

The broad underlying principle in permitting the private sector to own and operate banks is to ensure that ownership and control is well-diversified and sound corporate governance principles are observed. New private sector banks can initially enter the market with a capital of Rs 5 billion, which is the minimum net worth that should be retained at all times. In February 2013, fresh guidelines for licensing of new banks were issued. The guidelines permit business/industrial houses to promote banks, conversion of NBFCs into banks and setting up of new banks in the private sector by entities in the public sector, through a Non-Operative Financial Holding Company (NOHFC) structure.

In August 2016, RBI permitted ‘on tap’ licencing of new private banks to float universal banks (See Section III ). The guidelines have been liberalized since 2013, when IDFC Ltd and Bandhan Financial Services were allowed to set up universal banks.

The Universal bank has to get its shares listed on stock exchanges withing six years from commencement of business

Small Finance Banks (SFB)

Universal banks may not be in a position to understand or cater to the needs of small value customers. Hence, in November 2014, RBI gave approvals / licences for Small Finance Banks.

RBI issues licences to entities to carry on the business of banking and other businesses in which banking companies may engage, as defined and described in Sections 5 (b) and 6 (1) (a) to (o) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949, respectively

According to RBI guidelines dated November 27, 2014 (https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PressRelease/PDFs/IEPR1090GLS1114.pdf accessed at www.rbi.org.in), the objectives for setting up Small Finance Banks is to give a fillip to financial inclusion by (a) providing savings vehicles, and (b) supplying credit to small business units, small and marginal farmers, micro and small industries and other unorganized sector entities, through high technology, low cost operations.

Small finance banks can be established by (a) individuals/ professionals with 10 years’ experience in the banking and finance industry, (b) companies / societies owned and controlled by residents, (c) existing Non Banking Finance Companies (NBFC), Micro finance institutions (MFI) and Local Area Banks (LAB) owned and controlled by residents

The minimum paid up equity capital required is Rs 1 billion. Promoters’ minimum initial contribution should be 40%. Foreign shareholding will be determined by the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Policy for private sector banks.

The SFB would be required to follow all prudential norms and regulations applicable to commercial banks. Including maintaining cash reserve ratio (CRR) and Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR). The regulations are explained in subsequent chapter. SFB lending is to be made to sectors specified by RBI.

Ten Small finance banks have been granted licences upto March 2017. Of these, 8 are Microfinance institutions. They are listed below.

- AU Small Finance Bank

- Equitas Small Finance Bank

- Ujjivan Small Finance Bank

- Utkarsh Small finance Bank

- Janalakshmi Small Finance Bank

- Capital Lab Small Finance Bank (converted from a Local Area bank)

- Disha Small finance Bank

- ESAF Small finance Bank

- RGVN Small finance Bank

- Suryoday Small Finance Bank

Why are Microfinance Institutions evincing keen interest on converting themselves to Small Finance Banks?

Microfinance institutions (MFIs) are a category of Non Banking Finance companies (NBFC), which are permitted to lend to Self Help Groups (SHG) or Joint Liability Groups (JLG) by borrowing funds from banks. When the MFIs convert to SFBs, they can access public deposits, and participate in the bank payment systems, such as issuing cheque books and e payments. SFBs can make bigger loans to small borrowers.

The operating guidelines for SFB were issued in October 2016, and can be accessed at https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/NT81A721DA1E8CE745659C469519A38B75FA.PDF

The detailed compendium of guidelines in July 2017 on Small Finance banks by RBI can be accessed at https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/NOTI138800F49EEDBC418A9CB662EB2DEE4759.PDF

Payments Banks

Payments Banks are essentially ‘narrow banks’. To safeguard deposits placed with it, a narrow bank does not undertake lending activities. Rather, it invests the majority of its deposits in ‘safe’ instruments such as government securities. ( The term ‘narrow banks’ was developed by Robert E Titan of the Brookings Institutions in 1987, and was developed thereafter by many economists).

In November 2014, this class of niche banks was authorised by RBI. This category of banks was termed “Payments Banks” and the overarching objective was to accelerate financial inclusion. Payments banks are intended to provide (a) small savings accounts and (b) payments/ remittance services to migrant labour workforce, low income households, small businesses, unorganized sector entities and other users. The guidelines for eligibility for establishing Payments Banks can be accessed at https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Content/PDFs/PAYMENT271114.pdf. The Operating guidelines for Payments banks were released by RBI in October 2016 (https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/NT8012D3D3858D194184981CAF033321AA26.PDF)

Payments banks are permitted to undertake only the following activities:

- Accept demand deposits. Payments bank will initially be restricted to holding a maximum balance of Rs. 100,000 per individual customer.

- Issue ATM/debit cards. Payments banks, however, cannot issue credit cards.

- Undertake payments and remittance services through various channels. Payments Banks basic business model is geared towards using newer mobile technology and payment gateways to enable transfers and remittances through mobile devices, and issue debit / ATM cards usable on ATM networks of all banks. Hence the operations of these banks should be fully networked and technology driven from commencement of business operations.

- Function as a Business Correspondent of another commercial bank, as allowed by the RBI guidelines

- Distribute non-risk sharing simple financial products like mutual fund units and insurance products.

Payments banks cannot use the funds sourced from the above activities for lending. However, the funds would have to be deployed as follows:

- As Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) with RBI

- Minimum of 75% of demand deposit balances should be invested as Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR), in eligible government securities or treasury bills with maturity up to one year

- Maximum of 25% of demand deposit balances should be held in current and time / fixed deposits with other commercial banks for operations and liquidity management

The following entities can create Payments banks:

- Existing non bank Pre paid Instrument (PPI) issuers

- Individuals / professionals

- Non Banking Finance companies (NBFC)

- Corporate Business Correspondents (BC)

- Mobile telephone companies

- Super market chains

- Companies

- Real sector cooperatives

- Public sector entities

The minimum paid up equity capital for setting up Payments banks is Rs 1 billion. The promoters of these banks should contribute at least 40% of the equity capital and hold their stake for the first five years after the banks commence business. Foreign shareholding in Payments Banks is permitted and subject to the foreign direct Investment (FDI) policy for private sector banks as amended from time to time. The current FDI policy states that the aggregate foreign investment in a private sector bank from all sources will be allowed upto a maximum of 74 per cent of the paid-up capital of the bank.

Since the Payments banks are intended as a tool for financial inclusion, they have to provide at least 25 per cent of physical access points including BCs in rural centres

The following Payments Banks have been permitted to function (as of June 2017):

- Airtel Payments Bank

- India Post Payments Bank

- Fino Payments Bank

- Jio Payments Bank

- Idea Payments Bank

- Paytm Payments Bank

Foreign Banks

The presence and expansion of Foreign banks in India is with a view to fostering the inherent potential for sustained growth in the domestic economy and growing integration into the global economy.

In 2004, RBI permitted foreign banks regulated by a central bank in their home countries, to establish Wholly Owned Subsidiaries (WOS) in India. In 2005, a roadmap for the presence of foreign banks in India was drawn up. The first phase of the roadmap spanned the period between March 2005 and March 2009. The second phase would be operationalised after a review of the experience in the first phase.

In the first phase, foreign banks already operating in India were allowed to convert their existing branches to WOS.

In the second phase from April 2009, only the WOS route is permitted for a foreign bank to operate in India. Once established, the regulation is non-discriminatory in India, as foreign banks enjoy near national treatment in the matter of conduct of business. However, to prevent domination by foreign banks, restrictions are placed on further entry of new WOSs when the capital and reserves of the WOSs and foreign bank branches in India exceed 20% of the capital and reserves of the Banking system in India.

Local incorporation of foreign banks as WOS is advantageous due to the following reasons:

- Local incorporation enables creation of separate legal entities that have their own capital base and local Board of directors;

- There is a clear distinction between the assets and liabilities of the foreign banks operating in India and those of their foreign parent banks;

- Local regulation and law enforcement is possible for better control

The initial minimum paid up capital for setting up the WOS is Rs 5 billion. If a foreign bank dilutes its stake in India to 74% or less, the existing FDI policy stipulates that the bank should list itself in India. The RBI guidelines in respect of foreign banks can be accessed at https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PressRelease/PDFs/IEPR936SC1113.pdf

INDIAN BANKS OPERATING OVERSEAS

There are 15 Indian banks (with187 branches) operating in various countries. They follow the local regulations when they operate outside India.

Regional Rural Banks (RRBs)

The RRBs were created for rural credit delivery and to ensure financial inclusion. Their capital base is held by the central government, relevant state government and the commercial bank that ‘sponsors’ them, in the ratio of 50:15:35, respectively. Recent policy initiatives include recapitalization and amalgamation of RRBs with their sponsor banks. So far, there have been two broad phases in the amalgamation of RRBs. In the first phase (September 2005–March 2010), RRBs of the same sponsor banks within a state were amalgamated bringing down their number to 82 from 196. In the second and ongoing phase, starting from October 2012, geographically contiguous RRBs within a state under different sponsor banks would be amalgamated to have just one RRB in medium-sized states and two/three RRBs in large states. In the current phase, 31 RRBs have been amalgamated into 13 new RRBs within 9 states to bring down their effective number to 56. Of these, 45 are profitable.

However, an issue that is considered to hamper performance efficiency of RRBs is the multiplicity of control—RBI is the banking regulator, while NABARD39 is the supervisor with limited supervisory powers.

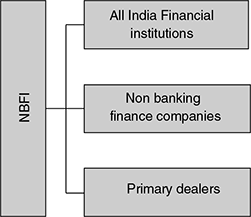

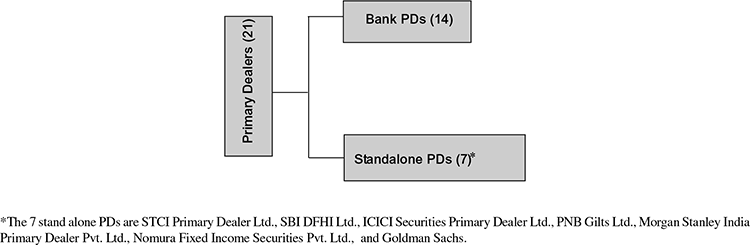

FIGURE 1.8B NON-BANKING FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS (NBFI)–THE COMPONENTS

Non-banking Financial Institutions (NBFIs) are a heterogeneous group of institutions that cater to a wide range of financial requirements. They can broadly be grouped as All India financial institutions (AIFIs), non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and primary dealers (PDs). The structure of these components is described in the following paragraphs.

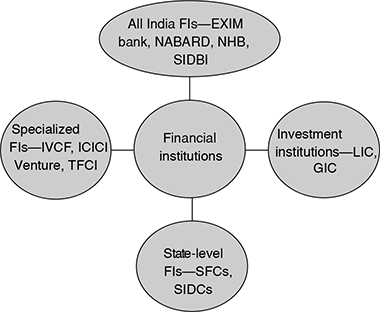

FIGURE 1.8C FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS’ STRUCTURE

Non Banking Financial Institutions (NBFI)

The ‘financial institutions’ (FIs) fall under the category of ‘Non-banking Financial Institutions (NBFI)40 that complement banks in providing a wide range of financial services to a variety of customers and stakeholders. While banks primarily provide payment and other liquidity related services, the NBFIs offer equity and risk-based products. However, this distinction is blurring now, as some financial institutions convert themselves into banks and ‘financial integration’ proceeds at a rapid pace.41

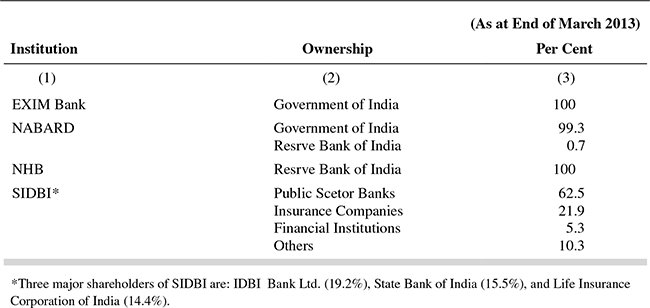

Based on their major line of activity, the four all-India financial institutions are classified into: (1) term-lending institutions (EXIM Bank), which invests in projects directly through investments and loans; and (2) refinancing institutions (NABARD - National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, SIDBI - Small Industries Development Bank of India and NHB - National Housing Bank). The refinancing institutions extend refinance to both banks as well as other NBFIs. Specifically, however, NABARD extends refinance and other facilities for agriculture and allied activities, SIDBI for the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) sector and NHB for the housing sector. Table 1.3 provides the ownership of these financial institutions

TABLE 1.3 ALL INDIA FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS – OWNERSHIP

Investment institutions, such as LIC and GIC deploy their resources for long-term investment. After the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority came into being in 1999, the sector—both life and non-life—have been thrown open for private and foreign participation.

State/regional level financial institutions comprise of State financial corporations (SFCs) and State Industrial and development corporations (SIDCs).

Some institutions, including a few from those listed above, have been notified as ‘public financial institutions’ by the Government of India under the Companies Act, 1956. Of these, a few have ceased operations (such as the Industrial Investment Bank of India), while some others have been converted into NBFCs (see the discussion on NBFCs, below). Examples of FIs converted into NBFC-ND-SI (see definition, below) are Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI) and Tourism Finance Corporation of India (TFCI).

Non Banking Finance Companies (NBFC)

The RBI Act 1934 was amended in January 1997 to bring in a comprehensive legislative framework for regulating NBFCs. The amendment called for compulsory registration and maintenance of minimum ‘net owned funds’ (NOF42—the concept of ‘capital’ for NBFCs), for all NBFCs and conferred powers on RBI to determine policies and issue directions to NBFCs.

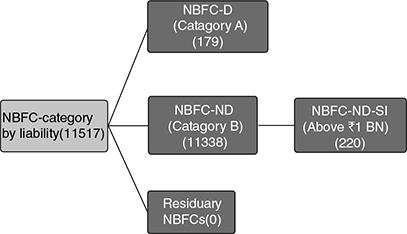

The two major categories of NBFCs in India are the deposit taking (NBFC-D) (from the public) and nondeposit taking (NBFC-ND) NBFCs. Housing Finance Companies (HFC) are considered a special type of NBFC. The residuary non-banking finance companies—RNBC, also accepts deposits from the public. Earlier, RNBCs held almost 90 per cent of all NBFC deposits, but their business model was found unviable. Hence, RNBCs were required to migrate to other business models. The two RNBCs exited the present business model by repaying their liabilities by 2015. Non-deposit taking NBFCs have been further bifurcated into NBFC-ND and NBFC-ND-SI, as shown in Figure 1.8D. ‘SI’ stands for ‘systemically important’. Understandably, NBFCs with asset size of over Rs 5 billion are classified in this category.

FIGURE 1.8D NBFC STRUCTURE BASED ON LIABILITIES

While deposit taking NBFCs (NBFC-D) were subject to some prudential regulation since 1963, the non-deposit taking institutions (NBFC-ND) were almost unregulated. As ‘systemic risk’ became a frequently used term and began threatening the stability of financial systems, RBI designated those NBFCs with asset size of over Rs 5 billion as ‘systemically important’ (NBFC-ND-SI), due to their linkages with money markets, equity markets, banks and financial institutions and brought them under a specific regulatory framework (capital adequacy and exposure norms43) from April 1, 2007. NBFC-ND-SI is the fastest growing segment of NBFCs, growing at a compound rate of 28 per cent between 2006 and 2008. They raise resources44 primarily from issue of debentures, borrowings from banks and other financial institutions and issue of commercial paper (a money market instrument, discussed in a later chapter). This category of NBFCs is closely monitored by RBI due to their systemic importance.

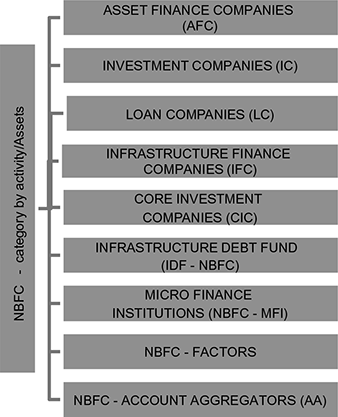

Figure 1.8E also shows another classification of NBFCs according to their asset profile. Across NBFC categories, asset finance companies (AFC) hold the largest share in total assets/liabilities (above 70 per cent). They are followed by loan companies (LC) with about 30 per cent.

FIGURE 1.8E NBFC STRUCTURE BASED ON ACTIVITY

It can be gauged from the above discussion that NBFCs, especially NBFC-NDs, do not have access to lowcost sources of funds like the banks do.45 Therefore, to compensate for high cost of funds, a significant segment of NBFC-ND companies have adopted a capital market based business model, such as providing loans against shares or financing public issues. While this is a model where high yields are possible, the risks are also higher.

Account Aggregators (AA) is the latest category of NBFCs authorised by RBI in September 2016 (https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/MD46859213614C3046C1BF9B7CF563FF1346.PDF). At present, financial asset holders such as holders of savings bank deposits, fixed deposits, mutual funds and insurance policies, get a scattered view of their financial asset holdings if the entities with whom these accounts are held fall under the purview of different financial sector regulators. This gap will be filled by account aggregators who will provide information on various accounts held by a customer in a consolidated, organised and retrievable manner. The option to avail the services of an account aggregator by a customer will be purely voluntary. The NBFC –AA will be regulated by RBI. The business model will be driven entirely by Information Technology (IT), and will be governed by a Citizens’ Charter for customer protection. The minimum Net Owned Funds (capital) requirement for an AA is Rs 2 crore. Once authorized, the AA will be bound by the terms and conditions of the licence that include customer protection, grievance redressal, data security, audit control, corporate governance and risk management. The AA will not involve itself in the financial transactions of customers. The pricing of its services will be in accordance with a policy approved by its Board of Directors.

Housing Finance Companies (HFC)

Housing finance companies (HFC) are special types of NBFCs. When the National Housing Bank (NHB), one of the all India financial institutions (described earlier) was set up in 1988, there were about 400 housing finance companies regulated by the RBI that financed only 20 per cent of the population’s home financing needs. The remaining 80 per cent was being financed through informal sources. Housing Development Finance Corporation (HDFC) was the largest housing finance company. The housing finance market has grown stupendously since then, with many banks and other institutions entering the sector. The NHB is the regulator and supervisor of HFCs.

Other types of NBFCs are Chit Funds that are regulated by the State Governments, and Mutual Benefit companies that are regulated by Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India. The multiplicity of regulators poses challenges in the functioning of the non banking sector

There are further regulatory challenges in this fast growing segment.

For example, RBI’s Panel for financial regulation and supervision classifies NBFCs into a third set of broad categories46:

- Stand-alone NBFCs.

- NBFCs that are subsidiaries/associates/joint ventures of banking companies.

- NBFCs and banks under the same parent company, i.e., ‘sister companies’.

- NBFCs that are subsidiaries/associates of non-financial companies.

FIGURE 1.8F PRIMARY DEALERS (PD)47 OPERATING IN FINANCIAL MARKETS

FIGURE 1.8G STRUCTURE OF THE CO-OPERATIVE BANKING SECTOR (END-MARCH, 2016)

Co-operative Credit Institutions

India has a large number and broad range of rural financial service providers—with formal financial institutions/ banks at one extreme, informal providers such as money lenders or traders at the other extreme and between these two, a large number of semi formal providers. The ‘formal’ providers include rural and semi urban branches of commercial banks, regional rural banks, rural co-operative banks and primary agricultural credit societies (PACS). The ‘semi-formal’ sector is characterized by self-help groups (SHGs) with bank linkages and the microfinance institutions (MFIs).

The co-operative sector was conceived as the first formal institutional channel for credit delivery to rural India. It has been regarded as a key instrument for achieving the ‘financial inclusion’ objective. The urban co-operative banks (UCBs) are an important channel for financial inclusion in the semi-urban and urban areas, especially for the middle- and low-income customers.

Though these institutions play a critical role in the financial sector, their commercial viability and financial soundness are seen as areas of concern. The size of the rural and co-operative sector is small when compared with the commercial banking sector. However, there are certain issues that have to be resolved if these institutions have to function efficiently.

A key issue that hampers efficiency is that these institutions’ operations are overseen by both the RBI/ NABARD and the relevant state governments, which leads to multiplicity of control. According to the committee on financial sector assessment (CFSA, 2009), the dual control is ‘the single most important regulatory and supervisory weakness’ in the co-operative banking sector.

Another issue causing concern is the management and governance of these institutions. Since, only borrowers are members, co-operatives could tend to frame and pursue borrower-oriented policies. Many co-operatives function as banks without proper licences. Further, directors are appointed mostly on political affiliation and rarely on merit. To introduce best practices and professional governance, the CFSA recommends (Chapter II, page 174) that co-operatives in India be modelled on the lines operated by the World Council for Credit Unions (WOCCU).48

The rural cooperative credit structure is shown in Figure 1.8G.

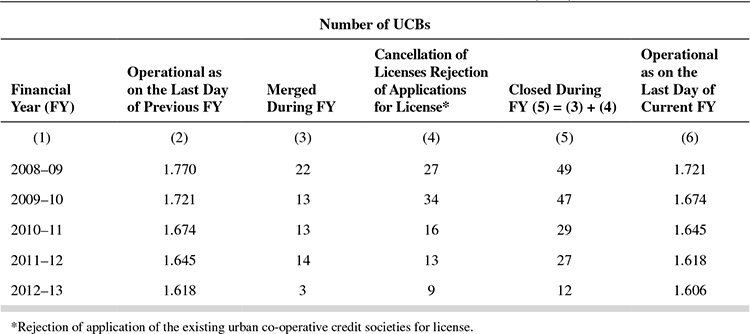

The RBI adopted a multi-layered regulatory and supervisory strategy aimed at the consolidation of UCBs by way of merger/amalgamation of viable UCBs and the exit of unviable banks for the revival of this sector, which led to a gradual reduction in the number of UCBs. The closures of UCBs were due to various reasons such as high non-performing advances, negative net-worth, deterioration in financial health, non-compliance with RBI guidelines, frauds, affairs conducted in a manner detrimental to the interests of depositors, misappropriation of funds, sanctioning of loans in excess of permissible limit, sanctioning of loans to the entity in which directors have interest, etc. The total number of UCBs as at the end of March 2016 stood at 1574 as against 1606 as at the end of March 2013. The progress of consolidation of UCBs is shown in Table 1.4.

TABLE 1.4 PROGRESS IN CONSOLIDATION OF URBAN COOPERATIVE BANKS (UCB)

Box 1.3 summarizes the major findings and recommendations of an Expert Committee on the short-term cooperative credit structure.

BOX 1.3 SHORT-TERM CO-OPERATIVE CREDIT STRUCTURE—FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Under-capitalization is one of the major problems afflicting the co-operative credit institutions.

Even after capital infusion to strengthen co-operative banks in July, 2013, 23 unlicensed banks in four states were unable to meet the licensing criteria as issuing of licences to these institutions is contingent upon their attaining minimum risk-weighted capital ratio of 4 per cent.

Against this backdrop, the Reserve Bank constituted an Expert Committee to examine the 3-Tier Short-term Cooperative Credit Structure (Chairman: Dr Prakash Bakshi) with a set of objectives: (i) to have a relook at the functioning of the Short-term Co-operative Credit Structure (STCCS) from the point of view of the role played by them in providing agricultural credit; (ii) to identify Central Co-operative Banks (CCBs) and State Co-operative Banks (StCBs) which may not remain sustainable in the long-run even if some of them have met the diluted licensing criteria; (iii) to suggest appropriate mechanisms for consolidating by way of amalgamation, merger, takeover, liquidation and delayering; and (iv) to suggest proactive measures to be taken by co-operative banks and various stakeholders.

The Committee submitted its report to the Reserve Bank in January 2013.

The major findings and recommendations of the Committee are:

Findings:

- STCCS’s share in providing agricultural credit dipped to 17 per cent at the aggregate level.

- STCCS, which was primarily constituted for providing agricultural credit must provide at least 15 per cent of the agriculture credit requirements in its operational area, gradually increasing to at least 30 per cent. Around 40 per cent of the loans provided by PACS and almost half the loans provided by CCBs are for non-agricultural purposes. PACS and CCBs were not performing the role for which they were constituted.

- About 209 of the 370 CCBs would require additional capital aggregating to `65 billion in four years to attain 9 per cent CRAR by 2016–17.

- Almost two-third of the deposits with StCBs is deposits made by CCBs in the form of term deposits for maintaining their SLR and CRR requirements. However, StCBs lend far higher amounts to the same CCBs and also invest in loans which have generally resulted in higher NPAs, thus putting the SLR and CRR deposits made by CCBs at risk.

Recommendations made by the committee are in the following broad areas:

- The co-operative credit institutions should fulfil the purpose for which they were constituted, namely, provide agricultural credit in rural areas. Penalties/deterrents are proposed for not fulfilling this primary objective.

- To enable the institutions to mobilize funds and disburse loans to meet these objectives, Amendments to the State Co-operative Societies Acts, rules and by-laws would be necessary in each state with regard to the definition of active members.

- The RBI would define the composition of capital for these institutions to enable meeting their objectives.

- The Banking Regulation Act needs to be amended to give direct and overriding authority to the Reserve Bank over any other law for superseding the Board or removing any director on the board of a StCB.

- CCBs and StCBs need to be covered by the Banking Ombudsman or a similar mechanism that may be developed by the Reserve Bank with NABARD.

An Implementation Committee has been constituted with members from NABARD and the Reserve Bank for expeditious implementation of these recommendations.

The implementation of these recommendations is likely to strengthen rural co-operative credit institutions.

RBI’s Discussion Paper titled “Banking structure in India: The way forward” published in August 2013, makes the following observations about the growth of UCBs.

“As UCBs become larger and spread into more states, the familiarity and bonding amongst their members diminishes and commercial interests of the members overshadow the collective welfare objective of the organisation. The UCBs lose their cooperative character. In the process, some of them become ‘too big to be a cooperative’. The collective ownership and democratic management no longer suit their size, and competition and complexities in the business force them to explore alternate form of ownership and governance structure to grow further. Corporatisation could be the best alternative for multi-State UCBs. UCBs enjoy arbitrage in terms of both statutory and prudential regulations. Only some provisions of Banking Regulation Act, 1949 are applicable to them. UCBs continue to be under Basel I capital framework. Though, these may not cause serious concerns when UCBs are small and their operations are limited, regulatory arbitrage may create incentives for large multi-State UCBs to have greater leverage. Their remaining under lighter regulation is a risk. Larger multi-State UCBs, having presence in more than one State, dealing in forex and participating in the money market and payment systems, could be systemically important. Their failure may have contagion effect and unsettle the UCB sector. The systemic risk could be minimized, by subjecting them to prudential regulations applied to commercial banks “

Reference

NABARD (2013), Report of the Committee to Examine Three-tier Short-term Co-operative Credit Structure, January, 2013. RBI,(2013), Discussion Paper, Banking Structure in India - The way forward, August 2013, page 51

Banking Models in India

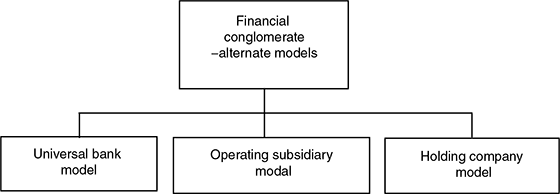

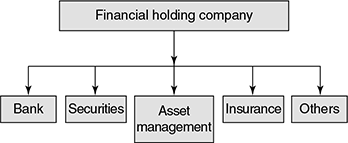

Figure 1.9 shows the ways in which financial conglomerates can be organized.

In the ‘universal bank’ model, all financial operations are conducted within a single corporate entity. In the ‘operating subsidiary’ model, operations are conducted as subsidiaries of a financial institution. In the ‘holding company’ model, financial operations are carried out by distinct entities (such as banks, mutual funds, insurance, NBFCs and HFCs), each with separate capital and management, but together owned by a single institution (financial or non-financial).

In India, the universal banking model is followed. In structuring universal banks, the conglomerate structure is bank-led, i.e., banks themselves are holding companies which operate certain businesses through Subsidiaries, Joint Ventures and Affiliates. The policy has evolved over a period of time. The current policy has been expounded in the FAQs on the New Banks Guidelines dated 3rd June 2013 (www.rbi.org.in). The general principle in this regard is that para-banking activities, such as credit cards, primary dealer, leasing, hire purchase, factoring etc., can be conducted either inside the bank departmentally or outside the bank through subsidiary/ joint venture /associates. Activities such as insurance, stock broking, asset management, asset reconstruction, venture capital funding and infrastructure financing through Infrastructure Development Fund (IDF) sponsored by the bank can be undertaken only outside the bank. Lending activities must be conducted from inside the bank

FIGURE 1.9 ALTERNATE ORGANIZATIONS FOR FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATES

Evolution of Indian Banking

The evolution of the Indian banking system can be categorized into four distinct phases:

- The pre-Independence (pre-1947) phase

- 1947–67

- 1967 to 1991–92

- 1991–92 (financial sector reforms) and beyond