CHAPTER ELEVEN

Capital—Risk, Regulation and Adequacy

CHAPTER STRUCTURE

Section II Risk-Based Capital Standards—Regulatory Capital (Basel norms)

Section III Application of Capital Adequacy to Banks in India

Section IV Illustrative Problems on Calculating Capital Adequacy

Suggestions for Further Reading

Annexures I, II (Case study), III, IV

KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM THE CHAPTER

- Understand why capital is so important for banks.

- Know what constitutes bank capital.

- Analyse what bank capital should be related to, if ‘safety’ of bank is to be ensured.

- Understand the difference between accounting capital, economic capital and regulatory capital.

- Learn to measure capital adequacy-Basel norms.

- Learn how Basel norms are applied in India.

SECTION I

BASIC CONCEPTS

Why Regulate Bank Capital?

Banking is undoubtedly one of the most regulated industries globally and the rules governing bank capital are one of the most prominent aspects of such regulation. Why should this be so?

There are two typical justifications presented for regulating banks—the risk of a systemic crisis and the inability of depositors (who are the primary creditors) to monitor banks. Bank failures1 are often triggered by the inability of banks to honour repayment commitments to their creditors on time. Modigliani and Miller, in their seminal work of 1958, contended that in perfect frictionless markets with full information, the value of a firm is independent of its capital structure. Most research on firms’ capital structure thereafter has studied the implications of deviations from the ‘perfect’. Taxes, financial distress, transaction costs, agency costs and asymmetric information are the important ‘imperfections’ considered to explain a firm’s capital structure. In the case of banks, research has added two other factors—banks’ access to the safety net, in particular, deposit insurance and the fact that most of the bank debt originates from small, generally uninformed depositors.1

In the traditional corporate finance view, capital reduces risk of failure by providing protection against unexpected losses (ULs). This is applicable to non-financial firms with relatively low financial leverage and reliance on long-term debt. Is the same argument applicable to financial intermediaries as well?

Consider the balance sheets of the two hypothetical firms in Table 11.1. One is a manufacturing firm and the other, a bank.2

TABLE 11.1 BALANCE SHEET OF TWO HYPOTHETICAL FIRMS

The following are the striking contrasts:

- The manufacturing firm has 60 per cent current assets and 40 per cent fixed assets. The bank has 77 per cent current assets and 3 per cent fixed assets.

- The manufacturing firm has a current ratio of 2, while the bank’s current ratio is less than 1.

- The manufacturing firm finances its assets with 60 per cent debt and 40 per cent equity. The bank finances its assets with 90 per cent debt and 10 per cent equity.

- The manufacturing firm can tolerate a 40 per cent fall in the value of its assets before its equity value is reduced to zero. It would take a mere 10 per cent fall in asset values for the bank to default on its liabilities.

- Therefore, the higher the capital, the higher the number of problem assets that can default before the capital is fully depleted.

Then why are banks permitted to operate with much more financial risk than manufacturing firms? Is it because banks, with low fixed assets, exhibit low operating leverage? However, market values of bank assets are more volatile than those of the typical manufacturing firm. Interest rate changes, borrower defaults or force majeure happenings can trigger changes in market values of bank assets, which are essentially financial assets. Though, theoretically, financial assets are more liquid and less risky than real assets (that manufacturing companies hold), in practice, these very assets could turn illiquid due to a variety of influencing factors.

We have seen in earlier chapters that bank liabilities and assets vary greatly by tenor, rate and composition. The assets bear the credit risk (borrower default), market risk (interest rate fluctuations) and the operational risks (failure of internal systems or people). Any one or a combination of these risks or an unanticipated disastrous event (force majeure risk) could result in eroding the value of banking assets.

On the other hand, the bank needs liquidity to pay off its creditors in accordance with the various contracts it has entered into at various points in time. This liquidity will have to primarily come from the periodic liquidation of assets (e.g., repayments, interest payments and sale of securities). If the assets start losing value, since assets = liability + equity, the bank would have to turn to its capital to keep up its liability commitments. If the capital is not augmented with fresh infusion of funds, the bank would run out of cash and face the most serious risk of all—liquidity and hence, solvency risk.

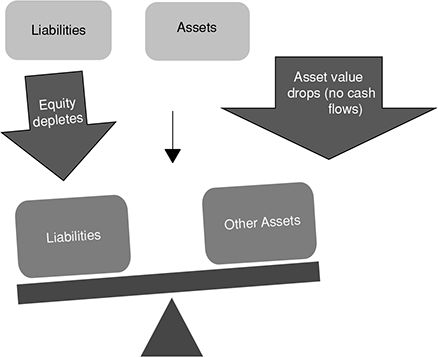

Diagrams 11.1 and 11.2 depict the relationship between asset value (cash flows) and the bank’s solvency. In the first, book values of liabilities and assets are matched. However, in the second case, the market value of assets erodes and the bank faces a solvency risk.

DIAGRAM 11.1 BOOK VALUE BALANCE SHEET OF A BANK – ASSETS AND LIABILITIES MATCHED

DIAGRAM 11.2 MARKET VALUE BALANCE SHEET OF A BANK – ASSET VALUE ERODES AND EQUITY USED TO MEET PART OF LIABILITIES

Thus, the greater the bank’s capital funds, the greater the amount of assets that can default before the bank becomes technically insolvent and lower the bank’s risk.

Apart from the vital function of absorbing losses as described above, which also ensures the long-term solvency of the bank, capital for a bank also serves other functions.

When a bank has adequate capital, it has ready access to the financial markets, since investors look upon it as a safe investment option. The bank can enter new businesses and can indulge in risk taking to boost earnings potential.

Thus, regulating the amount of capital that a bank should hold, though seen to constrain growth to some extent, is aimed at reducing the risk of banks expanding beyond their ability or taking undue risks.

To What Should Capital be Linked to Ensure Bank Safety?

How much capital is adequate? The debate goes on.

Take the hypothetical example given above. Let us assume that both the manufacturing firm and the banking firm have a return of 1 on their assets (ROA = 1). Which of the firms will have a higher return on equity (ROE)? Going by our analysis in the earlier chapter on ‘bank financial statements’, the ROE equals the product of the ROA and the equity multiplier (EM). The two firms’ Equity multiplier are 2.5 (for the manufacturing firm) and 10 (for the banking firm), respectively. This implies that the bank’s ROE is four times that of the manufacturing firm or that the latter should be able to flog its assets to produce an ROA, which is four times larger than what it is now!

What has contributed to this difference in the ROE? Financial leverage. Higher leverage improves profitability when earnings are positive.

More capital may ensure safety and stability, but may reduce profitability. Hence, bankers may prefer to operate with less capital.

Here lies the catch. What happens when the bank has risky or low quality assets whose earnings are being eroded either due to market factors or defaults? If the ROA slips to a negative slot, the bank’s profits slide tenfold! This implies that only low risk firms should have high financial leverage.

However, financial risk is inherent to banking business, quite incomparable with the traditional manufacturing firms. Hence, the inference becomes quite clear. Only if banks have low-risk assets can they remain safe. In practice; however, banking assets are risky.

Therefore, banks should increase capital relative to the risks of the assets they hold.

In this connection, please recall the discussion in the chapter on Bank financial statements, where the implication of the inverse of the equity multiplier (Assets/Equity) was mentioned. The inverse, Equity/Assets, indicates the number of assets that can default before the equity of the bank is entirely eroded. The better the quality of assets, therefore, the more safe is the bank. In other words, when the bank’s assets have low risk, the bank’s capital, and hence the bank’s solvency, is intact.

The Concept of Economic Capital3

If banks have to increase capital relative to the risk of the assets they hold, how should we determine how much capital would be adequate or required by banks to run the business, stay viable and survive?

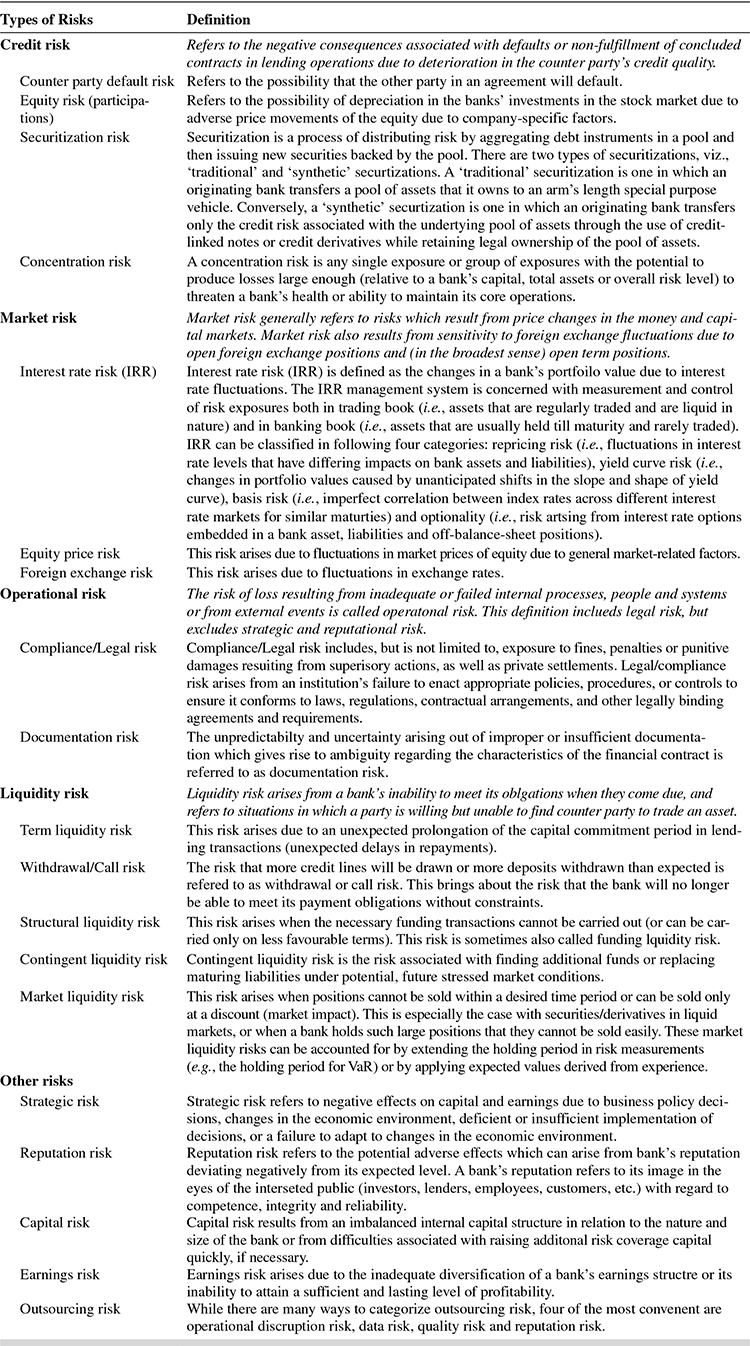

We have seen that the risk associated with banking services depends on the type of service, that ‘risk’ is inherent in banking business and banks cannot survive by merely avoiding risk. Table 11.2 provides an overview of the risks that banks face in various facets of their operations.

Since ‘risk’ is statistically defined as the adverse deviation of actual results from expected results, the likelihood of potential adverse outcomes can be modelled using mathematical/statistical techniques. The capital that is estimated to cover the probabilistic assessment of potential future losses is called ‘Economic Capital’ and logically, banks themselves would be in a position to assess the amount of capital they require to absorb potential losses associated with all the risks they face. This estimate of capital is bound to be different from the traditional accounting capital measure that appears on banks’ balance sheets. While the accounting capital represents book values, economic capital can be considered a forward looking measure of adequacy of capital to cover banking risks.

Thus, ‘Economic Capital’ can be defined as the amount of capital considered necessary by banks to absorb potential losses associated with banking risks—such as credit, market, operational and other risks. In recent times, many banks have been using advanced modelling techniques that incorporate the internal allocation of economic capital considered necessary to support risks associated with individual lines of business, portfolios or banking transactions. Banks also use economic scenarios generated stochastically to model future business and risks.

Statistically, economic capital is defined as the difference between some given percentile of a loss distribution and the expected loss (EL) and can be understood as protection against unexpected future losses at a confidence level selected by the bank management. Usually the 99.9 per cent confidence level is used. We have seen from earlier chapters that selecting a high confidence level would imply lower probability of insolvency. Hence, the economic capital required would be higher for higher confidence levels (See Figure 11.1).

Maintaining economic capital at the 99.9 per cent confidence level implies that the capital is sufficient to cover all but one worst possible risk loss out of 1,000 possible risk scenarios, for a given time horizon. In other words, economic capital would cover most of the Unexpected Loss (UL) events, except catastrophic events. This possibility for ‘ULs’ necessitates holding of capital protection.

The Concept of Regulatory Capital

The widespread banking crises in the last two decades have resulted in a number of regulations to prevent such occurrences. These regulations were earlier based on the notion that banks are prone to default on their committed deposit payments because of the mismatch between the timings of the demand for withdrawals and the returns on the assets that banks create. The possibility of such a mismatch can encourage depositors to withdraw larger amounts than they would have, if such possibilities did not exist. On a large scale, such depositors’ behaviour would result in a ‘run’ on the bank. Therefore, one aspect of bank regulation is to ensure that depositors who do not need to withdraw at present are given enough assurance that they will be paid in the future. Depositors need assurance that the bank has enough (claims on) liquid assets to meet all demands made by depositors. There are four ways to provide this assurance4—adequate bank equity capital, deposit insurance, lender of last resort and subordinated debt. Lack of assurance can lead to bank failures and outcomes that are not welfare maximizing. These assurances have an economic role in providing optimal outcomes and therefore, need to be formulated with utmost care.

FIGURE 11.1 ECONOMIC CAPITAL AND HEDGING TECHNIQUES FOR LOSSES

Basically, both regulatory and economic capital are concerned with the bank’s financial staying power. However, regulatory capital depends on the confidence level set by the regulator and therefore, does not respond in the same manner to changes in the common variables that affect both economic and regulatory capital, such as loans’ Probability of Default (PD) and Loss Given Default (LGD). Hence, no direct relationship has been perceived between both capital levels.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (see Section II) and the regulators however recognize that capital adequacy as determined by economic risk is imperative for the long term stability of banks. Therefore, apart from maintaining capital as stipulated by regulation, banks need to carefully assess their internal and future capital requirements based on the risks taken during the course of business.

Moreover, the two concepts reflect the needs of different stakeholders—the bank’s shareholders look to economic capital, while the depositors look to adequacy of regulatory capital.

Illustration 11.1 depicts a simple example of how regulatory and economic capital might be different.

ILLUSTRATION 11.1

Please refer to Illustration 9.1 (Chapter 9 – Managing Credit Risk – Advanced Topics)

In the measurement of credit VaR for a single loan using the Credit Migration Approach (Credit Metrics), we will compare the regulatory requirement of capital for the loan with the economic capital requirement for the same loan.

Regulatory capital specifies that (Indian norms) 9% risk weighted capital has to be maintained. Though our loan in the example is A rated, we will assume 100% risk weight for the loan. Hence, for ₹100 crore of the loan, the bank has to maintain regulatory capital of ₹9 crore.

Economic capital can be calculated as the Credit VaR either by assuming ‘normal’ distribution, or using the values in the actual distribution in the example.

- If we use normal distribution, we get the following results at 5% VaR and 1% VaR

5% VAR 1.65* ₹12.89 cr 1% VAR 2.33* ₹18.20 cr - If we use the actual distribution, we find that 5% VaR is approximated by 9.61% (adding the probabilities from the default state upwards i.e.,.009 + .007 + .002 + .044 + .072 + .827), and 1% VaR is approximated by 1.34% (add all probabilities except .827). At these values.

5% VAR 95% of actual distribution (125.63 – 126.89) ₹–1.26 crore 1% VAR 99% if actual distribution (125.63 – 125.67) ₹–0.04 crore

The VaR comes out negative in both cases, though, we can interpolate values to get to the 5% VaR level.

How do we interpret these results?

The results throw up some interesting observations, and in practice, challenges for banks when they have to maintain capital commensurate with the asset risk.

In our example of a ₹100 crore loan rated A, the bank would have to maintain ₹9 crore as capital to compensate for the credit risk in terms of the capital regulations. However, if the bank were to estimate the capital requirement based on its internal assessment of credit risk, it would have to maintain ₹18.20 crore as capital, if a normal distribution were assumed, or no capital at all, if the actual distribution were to be relied upon!

SECTION II

RISK-BASED CAPITAL STANDARDS5—REGULATORY CAPITAL

In the early 1980s, concern about international banks’ financial health increased, as did complaints of unfair competition. It was then that the BCBS began thinking in terms of setting capital standards for banks.

Box 11.1 provides an overview of the Bank for International Settlements and the Basel Committee.

BOX 11.1 THE BIS AND THE BCBS

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

The Bank for International Settlements, the world’s oldest international financial organization, was established in 1930 with its head office in Basel, Switzerland. It aims at fostering international monetary and financial cooperation and serves as a bank for central banks. The bank’s capital is held exclusively by 60 central banks of the world. The BIS fulfils its mandate by acting as:

- a forum for discussion and decision-making among central banks and within the international financial and supervisory community,

- a centre for economic and monetary research,

- a prime counter party for central banks in their financial transactions and

- agent or trustee in connection with international financial operations.

Sixty central banks, including the RBI, currently (as of July 2017) have rights of voting and representation at general meetings.

To maintain exclusivity as a bank for central banks around the world, the BIS does not accept deposits from or provide financial services to private individuals or corporate bodies. It is also not permitted to make advances to governments or open current accounts in the name of governments. However, it offers a wide range of financial services to central banks and other monetary authorities, such as the following:

- Management of foreign exchange reserves, a service used by 135 monetary authorities (at end of March 2009), to manage total currency deposits of SDR 197 billion, amounting to about 4 per cent of the world’s foreign currency reserves,

- Investment and asset management services for central banks, ranging from standard (such as sight/notice accounts and term deposits) to innovative, such as financial products to enable central banks to trade actively with BIS for increasing return on foreign assets, management of sovereign securities and other high grade assets and so on,

- Granting occasional collateralized short term credits to central banks and

- Acting as trustee for international government loans and performing collateral agent functions.

In order to further its objective of fostering international monetary and financial cooperation, the BIS undertakes the following activities:

- It organizes regular meetings of governors and other senior officials of central banks to enable them monitor global financial and economic developments and also discuss specific policy issues relating to monetary and financial stability.

- It hosts the secretariats of the BCBS (see below), the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems, the Committee on the Global Financial System, the Markets Committee and several others.

- To support the meetings and the work of the committees, BIS undertakes extensive research in the economic, monetary, financial and legal areas. It also functions as a hub for sharing statistical information among central banks and for publishing statistics on global banking securities, foreign exchange and derivatives markets.

- The Financial Stability Institute has been set up by BIS to promote dissemination and implementation of robust financial sector supervisory standards.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS)

The committee, established by central bank governors of the G10 countries in 1974, meets regularly four times a year. It has four main working groups, which also meet regularly.

The countries comprising the committee are represented by their central banks. The Committee reports to the governors of the central banks of the G10 countries. An important objective of the Committee is to tighten supervision of international banks towards achieving which the Committee has been working since 1975 and issuing a long series of documents. The Committee’s Secretariat is provided by the BIS in Basel. At the end of 2016, BCBS membership has expanded from the G10 to 45 institutions from 28 jurisdictions.

In 1988, the Committee introduced the bank capital measurement system popularly referred to as the Basel Capital Accord.

It should be noted that the Committee does not possess any formal supranational supervisory authority and its conclusions do not have legal force. Rather, it formulates broad supervisory standards and guidelines and recommends best practices to be customized and implemented suitably by individual authorities in various countries. In other words, the Committee encourages convergence towards common approaches and common standards.

More details of the functioning of the BIS can be accessed at www.bis.org.

The international convergence of bank capital regulation began with the 1988 Basel Accord on capital standards. The G10 countries signed the accord, which was then intended to apply to only internationally active banks. At that time, its focus was the measurement of capital and the definition of capital standards for credit risk. Since then the Accord has been amended several times, having been endorsed by the central banks of many countries and adopted by several banks across the globe. The first Basel Agreement (1988) contained some important features, which took into account the relationship between capital and the asset portfolio.

- It is directly linked by a simple formula, the capital requirement of a bank to the credit risk, determined by the bank’s asset composition. The greater the default risk of the asset portfolio, the higher the required capital.

- Recognizing the vital role of owner’s equity in capital it also prescribed, based on the risk profile of the assets, a minimum amount of equity capital.

- The capital norms were standardized across countries to ‘level the playing field’.

Over time, the Accord has been fine-tuned to account for financial innovation and some other risks it had not considered earlier.

Basel Accords II and III seek to strengthen the resilience and risk management capabilities of global banks. Basel III, the latest version of the Accord, aims at reinforcing global capital and liquidity rules, in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007–08. The salient features of the three Accords are provided in the remaining part of this Section (See Figure 11.2).

FIGURE 11.2 THE BASEL ACCORDS – TIMELINES

Demystifying the Basel Accords I, II and III

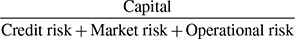

What do the successive Basel Accords really say? They do not mean anything different from what we have simplistically stated earlier about the relationship between bank capital and the risks of the assets banks carry. Therefore, the basic Basel definition of capital adequacy remains ‘Capital/Assets’, that can be now expressed as

![]() .

.

The Numerator of ‘Capital Adequacy’ Ratio We will start with the ratio ‘equity (capital)/assets’ mentioned earlier. What defines capital of a bank? Is it the book value of equity and reserves shown on the balance sheet, or is it the economic capital described in the previous section required to support risks? This is what the successive Basel Accords seek to define and measure. We know that equity capital has the last claim on the cash flows or assets of a firm. Hence, any instrument that satisfies this criterion, namely, staking the last claim on residual cash flows after all commitments are met, can be a part of bank capital. ‘Regulatory capital’ as defined by the Basel Accords adopts this approach and specifies some ‘equity like’ instruments that can be considered part of ‘capital’ of a bank. This is the numerator of the ‘capital adequacy ratio’. The ratio aims to ensure ‘adequacy of capital’ (in relation to asset risks) or simply measure ‘capital adequacy’ in regulatory terms. The successive Accords attempt to rigorously define and monitor the numerator.

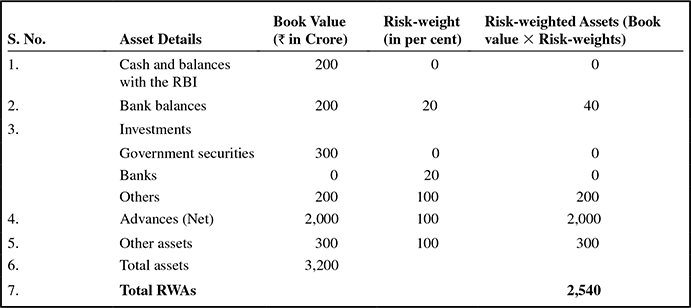

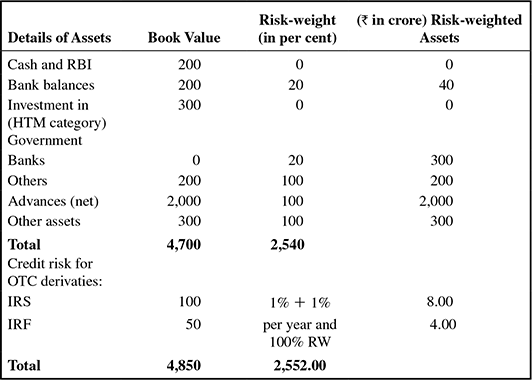

The Denominator of the ‘Capital Adequacy’ Ratio Let us now look at the denominator – ‘assets’. The discussion in the preceding section has established that rather than total assets of the bank the riskiness of the assets would determine how fast the bank’s capital would be eroded, and the bank would become insolvent. Hence, the denominator of the ‘capital adequacy ratio’ is ‘risk weighted assets’. Simply, each asset on the bank’s balance sheet is assigned a ‘risk weight’ (either by the regulator or by the bank itself through its internal models). The risk weight is multiplied with the asset value to arrive at the total of risk weighted assets. Risk weights are applicable not only to assets on the balance sheet of the bank, but also to contingent liabilities of the bank, since these can become potential future liabilities for the bank. ‘Credit conversion factors’ are used to arrive at a credit equivalent of the off balance sheet items, and then multiplied by the appropriate risk weights to compute the consolidated ‘risk weighted assets’ in the denominator.

‘Risk weighted assets’ (RWAs) are an integral part of the regulatory norms since they can (a) provide a common measure for banks’ risks, (b) ensure that capital maintained by banks is commensurate with the risks; and (c) potentially highlight where destabilizing asset class bubbles are arising6.

Since banks deal with complex instruments and risks, the successive Basel Accords have been fine tuning the ‘risk weighted assets’ to consider risks of counter parties, securitizations, derivatives, foreign exchange and other market related risks. ‘Operational risks’ that impact asset value are also considered part of ‘risk weighted assets’.

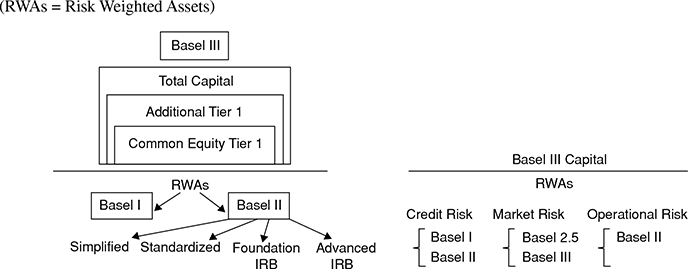

How Successive Basel Accords Have Treated ‘Capital Adequacy’ Basel I and Basel II (as well as Basel 2.5) concentrated on the measurement of the riskiness of assets in the denominator and the calculation of ‘risk weighted assets’. The numerator, ‘capital’ was also defined to bring out the difference between permanent capital of the bank augmented by reserves, and other types of capital that would typically not be shown on the balance sheet as equity capital. As the Accords progressed, the various versions of the numerator, ‘capital’ and the denominator, ‘risk weighted assets’ aimed at fine tuning their definition and measurement

The manner in which the various versions have dealt with the concept is shown in Figure 11.3

FIGURE 11.3 EVOLUTION OF THE CAPITAL ADEQUACY RATIO OVER THE BASEL ACCORDS

It can be understood from the Figure 11.3 that in Basel III, the focus is on the definition and composition of the numerator, ‘capital’, and the denominator ‘risk weighted assets’ is largely being carried over from the previous approaches.

Basel I, II and III are briefly described in the remaining portion of this section.

Basel Accord I

The 1988 Basel Accord required internationally active banks in G10 countries to hold capital equal to at least 8 per cent of a basket of assets measured in accordance with their risk profiles. The definition of ‘capital’ is broadly set in two tiers—Tier 1 being shareholders’ equity and retained earnings and Tier 2 being the additional internal and external sources available to the bank. The bank has to hold at least half of its measured capital in Tier 1 form.

A portfolio approach is taken to measure risk, with assets classified into four discrete buckets—10 per cent, 20 per cent, 50 per cent and 100 per cent—according to the quality of the assets. This means that some assets have no capital requirements, being considered riskless, while others have risk-weights attached to them. The two principal objectives of the Accord were: (a) to ensure an adequate level of capital in the international banking system and (b) to create a ‘more level playing field’ in competitive terms so that banks could no longer build business volumes without adequate capital backing.

The Accord was adopted as a world standard in the 1990s, with more than 100 countries applying the Basel framework to their banking systems.

However, the drawbacks in the framework were as listed below.

- The regulatory measures were seen to be in conflict with increasingly sophisticated internal measures of economic capital.

- The simple bucket approach with a flat 8 per cent charge for claims on the private sector resulted in banks moving high quality assets off their balance sheets, thus reducing the average asset quality.

- The Accord did not sufficiently recognize credit risk mitigation techniques.

When the Accord was introduced in 1988, its very design was questioned since the capital ratios appeared to lack economic foundation, the risk-weights did not reflect the risk of the borrower, and it did not account for any benefits from diversification of the asset portfolio. Growing experience and research prompted development of various alternatives to the Accord’s ‘buckets’ framework for setting capital standards.

Basel Accord II

It was recognized that the ‘one-size-fits-all’ framework of the Basel I Accord had to be upgraded, since each bank had its own unique way of measuring, mitigating and managing risks. The revised framework hence provides a spectrum of approaches ranging from simple to advanced for measurement of credit risks, market risks and operational risks, all of which could lead to asset quality and value deterioration. The framework also builds in incentives for better and more accurate risk management by individual banks.

The new Accord aims at a framework, which will maintain the overall ‘safety’ level of capital in banks through more comprehensive and risk sensitive approaches. It is less prescriptive than its predecessor and offers a range of approaches for banks capable of scaling up to more risk sensitive methodologies.

Structure of the New Accord The new Accord is based on three mutually reinforcing ‘pillars’, which together are expected to contribute to the safety and soundness of the international financial system (see Figure 11.4).

First pillar—Minimum capital requirement: The minimum capital requirement will now take into account market risks and operational risks, along with credit risks. It also proposes differentiated approaches to measurement of capital from basic to advanced.

- Capital for credit risk

- Standardized approach

- Internal ratings based approach—Foundation and advanced

- Securitization framework

- Capital for market risk

- Standardized approach (maturity method)

- Standardized approach (duration method)

- Internal models method

- Capital for operational risk

- Basic indicator approach

- Standardized approach

- Advanced measurement approach (AMA)

The salient features of these three approaches to measuring ‘risk weighted assets’ are provided in the following paragraphs:

FIGURE 11.4 THE PILLARS OF BASEL II ACCORD

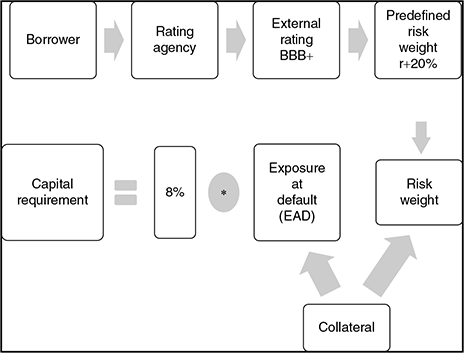

Credit Risk Measurement: Credit risk refers to the negative consequences associated with defaults or non fulfilment of concluded contracts in lending operations due to deterioration in the counter party’s credit quality.

- In the ‘Standardized’ approach, the risk weight depends largely on external credit ratings provided by accredited credit rating agencies. (For more details on credit rating and credit rating agencies, please refer to the Chapter ‘Uses of bank funds–the lending function’)

- In this case,

regulatory capital = 8 per cent × risk weight × notional amount.

For example, a BBB rated corporate borrower will attract 100 per cent risk weight. 8 per cent is the minimum capital that is to be maintained on the exposure to this corporate borrower. Hence, if the notional amount outstanding is ₹1000 crore, the regulatory capital to be maintained on this exposure would be 8 per cent × 100 per cent × 1000 = ₹80 crore

- In this case,

- In the Foundation—Internal Ratings based approach (F-IRB), banks would use internal estimates of Probability of Default (PD), and regulatory values for Loss Given Default (LGD) and Exposure at Default (EAD). (For more details on PD, LGD and EAD, please refer to the chapters on ‘Managing Credit Risk’)

- Banks can form their own assessment of ‘risk components’, after approval from their regulators/central banks. The risk components are—PD, LGD, EAD and M (Maturity—denoting effective maturity of every instrument).

- The second key element of the IRB framework is definition of the ‘risk weight functions’. These are the means by which risk components are transformed into risk weighted assets, the denominator of capital adequacy ratio. The risk weight functions are derived from the estimates of ‘risk components’.

- The third key element is definition of ‘minimum requirements’—the minimum standards that must be met by a bank using the IRB approach for an asset class.

- Banks moving to Advanced Internal Ratings Based approaches (advanced IRB) would use internal estimates of PD, LGD and EAD.

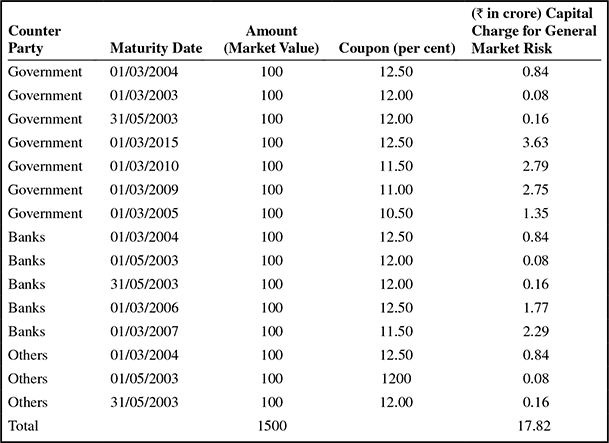

Market Risk Assessment: Market risk is defined as the risk of losses in on and off-balance-sheet positions arising from movements in market prices. The risks pertaining to interest rate related instruments and equitiesin the trading book, foreign exchange risk and commodities risk throughout the bank are key components of market risk.

- The standardized approaches use risk weights provided by the supervisor.

- The Internal Models Method (IMM) allows banks to use risk measures derived from their own internal risk management models. (Please also refer to some market risk measurement tools mentioned in the previous chapter).

- Basel 2.5 is a complex package of rules that imposes higher capital charges on banks for the market risks they run in their trading books, particularly credit-related products.

Operational Risk Measurement: Operational risk is defined as the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events (e.g., fraud, system failures). This definition includes legal risk, but excludes strategic and reputational risk.

- Under the Basic Indicator Approach, capital is a fraction of gross income. Banks using the approach must hold capital equal to the average over the previous three years of a fixed percentage (termed α = 15 per cent) of positive annual gross income.

- In the Standardized approach, capital is computed by lines of business using fixed percentages. Banks’ activities are divided into eight business lines. Within each business line, the capital charge is calculated by multiplying gross income by a factor termed β assigned to that line of business. For example, the β factor for corporate finance is 18 per cent, for commercial banking is 15 per cent, for retail banking 12 per cent and so on.

- Advanced Measurement Approach requires banks to use statistical methods and data analytics to calculate capital. Under this approach, the regulatory capital requirement will equal the risk measure generated by the bank’s internal operational risk measurement system using quantitative and qualitative criteria.

Calculation of Capital Adequacy Under Basel II

The ‘Capital ratio’ is expressed as follows:

The minimum ratio that a bank should maintain under the given formula is 8 per cent.

Credit risk is calculated as the aggregate of risk weighted assets under each applicable asset class. In the case of Market and Operational risks, risk-weighted assets are determined by multiplying the capital requirements (termed ‘capital charge’) for both risks by 12.5 (i.e., the reciprocal of the minimum capital ratio of 8 per cent) and adding the resulting figures to the sum of risk-weighted assets for credit risk.

Comparison of Basel I and Basel II

| Basel I | Basel II | |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity | Simple | High complexity |

| Approach | Top down—supervisor determines risk weights | Bottom up—Banks/external agencies determine risk weights |

| Approach to risk | No risk sensitivity | Increased risk sensitivity |

A detailed description of the determination of Risk weighted assets under the above approaches, definition of ‘capital’ and calculating the capital requirement under Basel II and Basel 2.5, can be found in Annexure I.

Second pillar—Supervisory review process. Bank managements are expected to strengthen their internal processes to set targets for capital commensurate with the risk profile and control environment of each bank. The internal processes would be subject to more rigorous review and intervention by the country’s central bank.

Third pillar—Market discipline. This aims at bolstering market discipline through enhanced disclosure by banks. The new framework sets out disclosure requirements and recommendations in several areas, including the manner in which a bank calculates its capital adequacy and its risk assessment methods. The core set of disclosure requirements is applicable to all banks.

How do the above approaches compare with the previous Accord? It can be seen that basel has shed the buckets approach which treated all banks alike, with no incentives for safer banks to differentiate themselves from riskier ones and thus save on capital. The present approach is an improvement since the buckets are now based on risk measures rather than on types of assets. This would bring regulatory capital for each exposure into closer alignment with the risk of the underlying asset and encourage banks to adopt better risk management practices.

Basel Accord III7

Shortcomings in Basel II

Some of the flaws pointed out in the Basel II proposals were as follows:

- The main criticism against Basel I was that it had a ‘one size fits all’ and ‘risk insensitive’ approach. Basel II brought in ‘risk sensitive’ capital regulation. However, the risk sensitivity made Basel II blatantly ‘procyclical’—that is, in good times, when banks are doing well, and the market is willing to invest additional capital in banks, Basel II does not demand more capital from banks. However, in bad times, when markets run out of or are unwilling to supply additional capital, Basel II requires that banks bring in more capital to support stressed assets. The happenings during the financial crisis of 2007, where major international banks could not bring in additional capital under pressure, bear out this observation about Basel II.

- Basel II failed to promote frameworks for accurate and realistic measurement of risk. Thus, the regulations could not demand sufficient loss absorbing capital to mitigate the risks caused by changes in market dynamics. For example, the financial crisis happened when market risk models failed to factor in the real risk from complex derivative products, on the simplistic assumption that these were tradable instruments that could be sold readily in the market. Hence, banks did not adequately cover these risks with capital. Additionally, banks started converting their assets into tradable instruments (the ‘originate and distribute’ model) to minimize capital holding.

- Basel II did not explicitly address the issues of excessive leverage and liquidity risk in banks. The assumption was that risk based capital would automatically mitigate the risk of excessive leverage. However, it was excessive leverage that triggered the financial crisis. The loss of liquidity that quickly followed excessive leverage led to banks becoming insolvent. The excessive leverage-liquidity risk–solvency risk relationship was not adequately recognized by Basel II.

- Basel II also focussed on individual banks and financial institutions and failed to take into consideration the ‘contagion’ effect of failure of one large bank. The risks to the global banking system arising from the interconnectedness of large institutions was a major reason for the crisis spreading rapidly across the financial system.

- Other issues that rendered Basel II ineffective against a major crisis were

- Pillar 1 does not penalize credit concentration. Instead, the issue of credit concentration risk is embodied as part of Pillar 2. In other words, the onus of identifying and penalizing credit concentration is left to supervisory review.

- All aspects of Counter party risk were not covered and there was no provision to include certain types of specialized derivative products in the risk measurement.

- On the issue of Pro cyclicality, it was noted that banks’ risk measurements were more at a specific point in time rather than over the whole asset cycle. Also, profit recognition and compensation schemes were seen to encourage short term risk taking. The risk over the business cycle was ignored.

Annexure II to this chapter gives more viewpoints on Basel II and its role in the blame game for the financial crisis of 2007.

The Move to Basel III Basel III, as we can see from the following paragraphs, makes an effort to fix the lacunae in Basel II that came to light during the financial crisis as also to reflect other lessons of the crisis. It is also evident that Basel III does not jettison Basel II, but builds on the essence of Basel II—the link between the risk profiles and capital requirements of individual banks. In that sense, Basel III can be considered an enhancement of Basel II.

The enhancements of Basel III over Basel II are primarily in four areas: (i) augmentation in the level and quality of capital; (ii) introduction of liquidity standards; (iii) modifications in provisioning norms; and (iv) better and more comprehensive disclosures. It is noteworthy that Basel III has concentrated on capital definition (the numerator of the capital adequacy ratio), with minimal enhancements in the risk measurements ( denominator of capital adequacy ratio).

Diagram 11.3 depicts the structure of Basel III guidelines and the comparison with Basel II.

DIAGRAM 11.3 BASEL III BASIC STRUCTURE AND BROAD COMPARISON WITH BASEL III

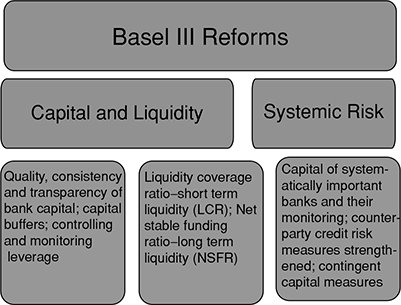

Objectives of Basel III According to the Basel committee, the Basel III proposals have two primary objectives:

- To strengthen global capital and liquidity regulations. The goal is to promote a more resilient banking sector

- To improve the banking sector’s ability to absorb shocks arising from financial and economic stress

To achieve these objectives, the Basel III proposals have focussed on the areas of capital reform, liquidity reform and other reforms that would improve the stability of the global banking system. The key ingredients of these reforms are presented in Diagram 11.4

DIAGRAM 11.4 BASEL III – PROPOSED REFORMS TO ACHIEVE OBJECTIVES

Each of the reforms are briefly discussed in the paragraphs below

Some Specific Enhancements Proposed in Basel III (Over Basel II)

- New definition of capital:

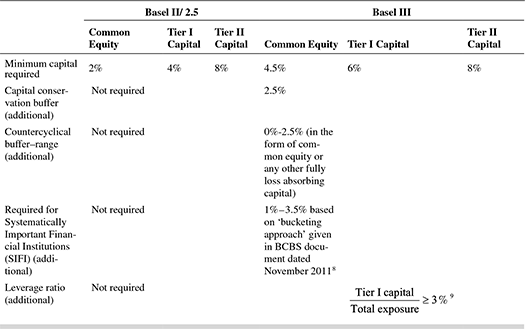

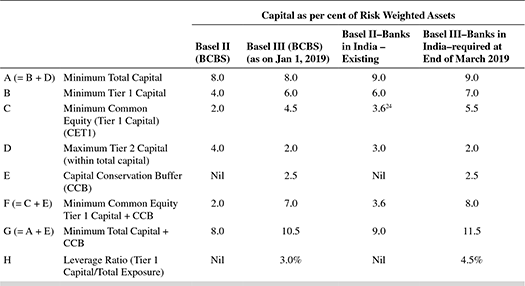

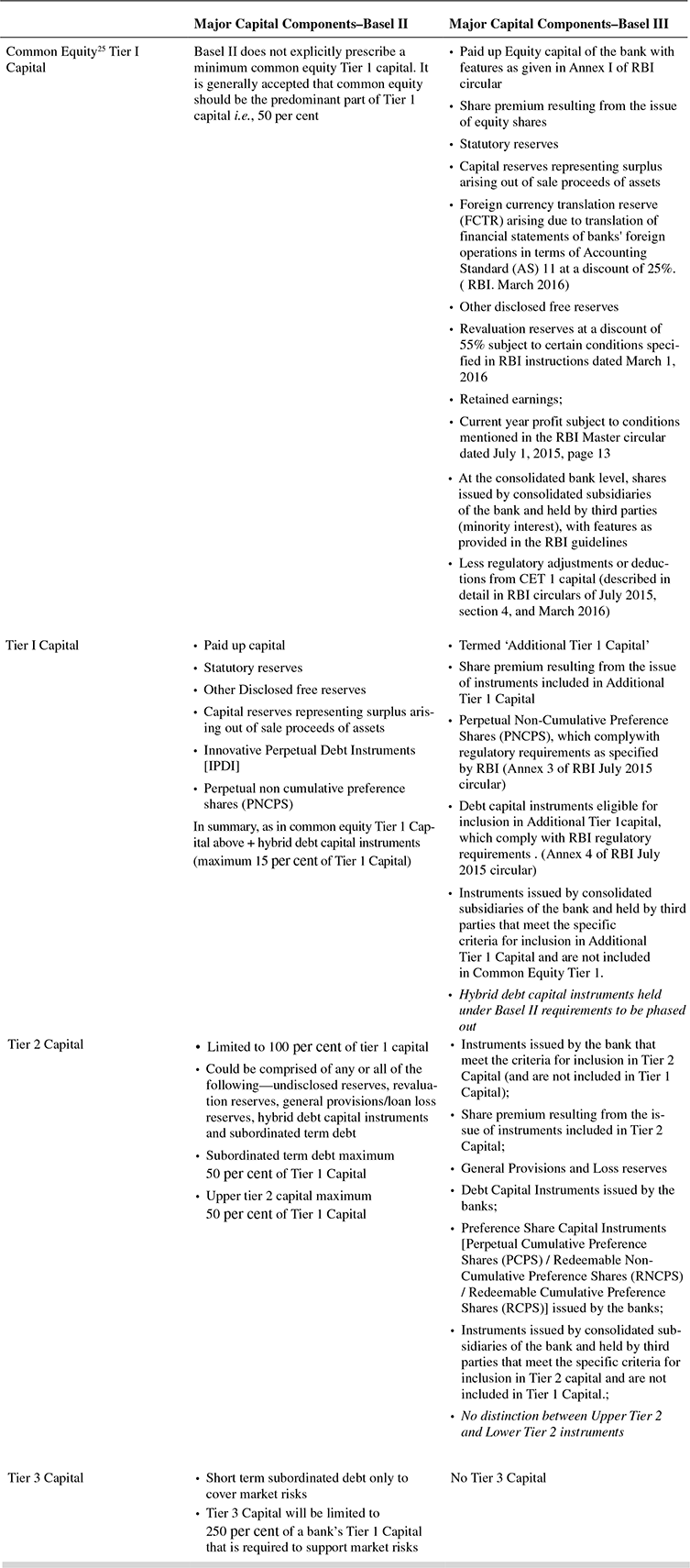

Table 11.3 distinguishes the capital requirements under Basel II and Basel III

It is not only the quantity of capital that has changed from Basel II as can be seen in the above table, but also the quality of capital required under the various categories of capital have undergone a change. Table 11.4 summarizes the key changes.

TABLE 11.4 BASEL II AND III CAPITAL REQUIREMENTS COMPARED – QUALITY OF CAPITAL

Table 11.5 shows the composition of capital items under Basel II and Basel III

TABLE 11.5 BASEL II AND III CAPITAL REQUIREMENTS COMPARED – COMPOSITION OF CAPITAL

In essence, in order to qualify, the additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 instruments in Basel III must have the following features:

- They must be more loss absorbing

- They must not contain incentives to redeem prior to their stated maturity

- They must be written off or converted to equity at the determination by the supervisory authority—that either the bank would not be viable without the write off or that a public sector capital infusion is essential .

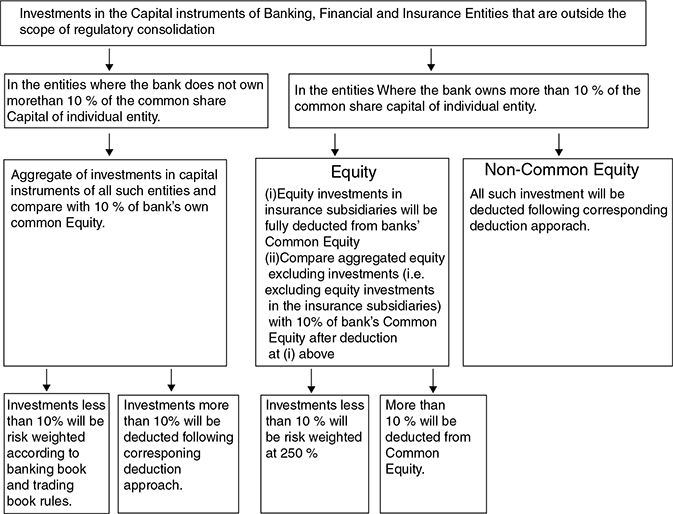

All the above capital classes are also subject to ‘regulatory adjustments’. Some of these adjustments are listed below:

- ‘Goodwill’ or other ‘intangible assets on banks’ balance sheets have to be deducted from Common Equity Tier 1 capital

- Deferred Tax Assets (DTAs) that rely on future profitability of the bank to be realize dare to be deducted in the calculation of Common Equity Tier 1.

- Gain on sale related to securitization transactions to be deducted from Common Equity Tier 1

Other adjustments mentioned by the Basel document related to ‘cash flow hedge reserve’, ‘shortfall of stock of provisions to expected losses, ‘cumulative gains and losses due to changes in own credit risk on fair valued financial liabilities’, ‘defined benefit pension fund assets and liabilities’, ‘investments in own shares’, ‘reciprocal cross holdings in banks and other financial entities’, etc.

The essential difference between Basel II and III Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital is that:

- Under Basel II, qualifying Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital was determined on the basis of ‘gross’ instruments, before deduction of various items that could reduce the amount of capital available to withstand credit and other shocks

- Under Basel III, banks would determine available Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital only after deductions are made

- Additional requirements as part of capital—the capital conservation buffer:

As can be seen from the comparative data presented above, Basel III requires higher and better quality capital. The minimum total capital remains unchanged at 8 per cent of Risk Weighted Assets (RWA). However, Basel III introduces a capital conservation buffer of 2.5 per cent of RWA over and above the minimum capital requirement, raising the total capital requirement to 10.5 per cent against 8.0 per cent under Basel II.

This buffer is intended to ensure that banks are able to absorb losses without breaching the minimum capital requirement, and are able to carry on business even in a downturn without deleveraging. This buffer is not part of the regulatory minimum; however, the level of the buffer will determine the dividend distributed to shareholders and the bonus paid to staff.

According to the Basel committee, ‘The framework reduces the discretion of banks which have depleted their capital buffers to further reduce them through generous distributions of earnings. In doing so, the framework will strengthen their ability to withstand adverse environments’. {page 55)

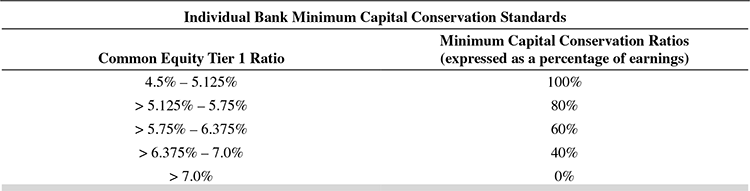

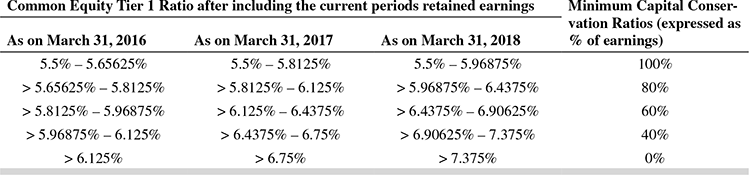

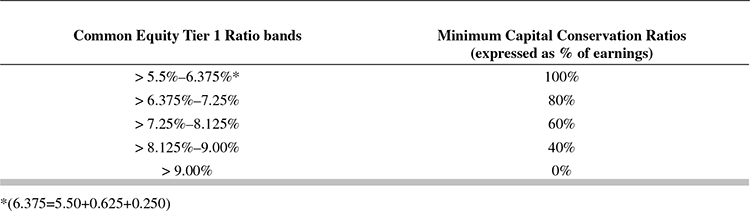

Table 11.6 from the Basel document shows the minimum capital conservation ratios a bank must meet at various levels of the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratios, and its impact on earnings distribution of banks

TABLE 11.6 IMPACT OF CAPITAL CONSERVATION BUFFER ON BANK CAPITAL AND EARNINGS DISTRIBUTION

Source: Basel Committee on banking supervision, Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems, revised version, June 2011, page 56.

Source: Basel Committee on banking supervision, Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems, revised version, June 2011, page 56.Let us interpret the table. A bank with CET1 capital ratio of say 5.5 per cent is required to pay out no more than 20 per cent of its net earnings as dividends or bonus payments or share buybacks in the following financial year. In other words, the bank has to conserve 80 per cent of its earnings over the following year. The motive is obvious—to curb excessive bonus and dividend payouts by banks at the cost of its stability and solvency.

If the bank still wants to make payments in excess of the prescribed limits, the bank has the option of raising more capital to equal the amount it wants to distribute over and above the limit. The option has to be discussed with the central bank/regulator as part of the bank’s capital planning process.

- Countercyclical buffer:

The financial crisis of 2007 came in the aftermath of a period of booming credit growth. A period of downturn succeeding excessive credit growth can destabilize not only the banking system but entire economies, as was evident from the events that followed the crisis. It is therefore important that the banking sector builds up additional capital defences to safeguard the macro-financial environment.

As the name suggests, this is an additional capital buffer. It is to be maintained in the proportion of 0–5 per cent of risk weighted assets that would be imposed on banks in periods of high credit growth. The buffer requirement should be met entirely from CET1 capital.

The National regulatory authorities would set the counter cyclical buffer, with the discretion of raising the buffer beyond 2.5 per cent of RWAs. The buffer would be set by public announcement. To enable banks build the buffer, a proposed increase in the buffer would have to be announced twelve months in advance. However, decisions to decrease the buffer would take effect immediately. Buffers would apply to banks based on geographic composition of credit exposures.

The implementation of this buffer is closely linked to the capital conservation buffer (CCB) described above. The following is an extract from the Basel III document, page 60.

Individual Bank Minimum Capital Conservation Standards Common Equity Tier 1 (including other fully loss absorbing capital) Minimum Capital Conservation Ratios (expressed as a percentage of earnings) Within first quartile of buffer 100% Within second quartile of buffer 80% Within third quartile of buffer 60% Within fourth quartile of buffer 40% Above top of buffer 0% For illustrative purposes, the following table sets out the conservation ratios a bank must meet at various levels of common Equity Tier 1 capital if the bank is subject to a 2.5 per cent countercyclical buffer requirement.

Individual Bank Minimum Capital Conservation Standards, When a Bank is Subject to a 2.5% Countercyclical Requirement Common Equity Tier 1 (including other fully loss absorbing capital) Minimum Capital Conservation Ratios (expressed as a percentage of earnings) 4.5% – 5.75% 100% > 5.75% – 7.0% 80% > 7.0% – 8.25% 60% > 8.25% – 9.5% 40% > 9.5% 0% It is evident from the above that the capital conservation buffer and the countercyclical buffer combine to determine the required retained earnings and profit payouts of banks. If a bank breaches the buffer, the amount of profits it can distribute to shareholders and employees can be restrained.

- Leverage ratio:

The 2007 financial crisis demonstrated that banks showing strong risk based capital ratios in accordance with Basel II, could also be excessively leveraged. The build up of excessive leverage was due to both on and off balance sheet activities. The Basel Committee has therefore introduced a ‘simple, transparent, non risk based leverage ratio to act as a credible supplementary measure to the risk based capital requirements’ (page 61).

The leverage limit is set at 3 per cent. This implies that a bank’s total assets (including both on and off balance sheet assets) should not be more than 33 times the bank’s capital.

The leverage ratio is proposed to be calculated as

The ratio should be ≥3 per cent.

The leverage ratio is proposed to be calculated as the simple arithmetic mean of the monthly leverage ratios over the quarter, and is to be tested during the parallel run period of January 1, 2013 to January 1, 2017.

‘Tier 1’ capital in the numerator would include both CET1 and Additional Tier 1.

The ‘exposure’ in the denominator would follow the accounting measures for both on and off balance sheet items. While the asset values will be captured from the balance sheet, the off balance sheet items will be considered at their credit conversion factors, and derivatives with Basel II rules (of netting) and a simple measure of potential future exposure (using the Basel II framework). Hence both off balance sheet items and derivatives are converted to ‘loan equivalents’.

- Liquidity requirements:

Being ‘liquid’, or having enough cash to pay liabilities as and when they fall due and honour other commitments, is one of the most celebrated aspects of banking. This vital requirement was put to severe test during and just after the financial crisis of 2007.

Before the crisis struck, asset markets were buoyant and funding was available readily and at low cost. Liquidity conditions deteriorated rapidly as the crisis progressed, and the banking system faced severe stress. According to the Basel committee, the difficulties experienced by some banks were due to lapses in basic principles of liquidity risk management. These principles, published by BCBS (the following chapter contains a summary of these principles) in 2008, have been complemented with more stringent minimum standards for funding liquidity.

Basel III introduces a new liquidity standard through two liquidity ratios.

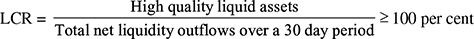

- The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) is designed to improve the short term resilience of the liquidity risk profile of banks. It requires banks to hold a buffer of ‘high quality’ liquid assets to match net liquidity outflows during a 30 day period of stress. In other words, the ratio shows if the bank can survive an acute stress scenario lasting for a month.

High quality liquid assets are defined by the Basel document as ‘unencumbered, liquid in markets during a time of stress and, ideally, be central bank eligible.’

The reporting frequency for the LCR should be not less than monthly. The LCR would be mandatorily reported from January 1, 2015, while the observation period starts from January 1, 2013.

A detailed description of the ratio and its components can be found in the document ‘Basel III: International framework for liquidity risk measurement, standards and monitoring’, published in December 2010, that can be accessed at www.bis.org

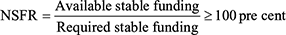

- The Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) is designed to promote resilience in the longer term. It requires that banks fund their activities with more stable sources of funding on an ongoing basis. More specifically, assets currently being funded and any other contingent obligations that may require funding must be matched by sources of stable funding over a one year horizon

The numerator, ‘Available Stable Funding’ (ASF), is calculated using ASF factors of 100 per cent, 90 per cent, 80 per cent, 50 per cent, and 0 per cent, to reflect the stability of the funding sources, multiplied by the amount of available funding over the horizon. For example, Tier 1 capital will have an ASF factor of 100 per cent, while unsecured wholesale funding would have an ASF factor of 50 per cent.

The denominator, ‘Required Stable Funding’ (RSF), is also calculated using RSF factors ranging from 0 per cent (for example, cash) to 100 per cent (for example, loans to retail or SME customers with remaining maturity of less than one year would have an RSF factor of 85 per cent).

NSFR will be a required standard from January 1, 2018, and the reporting will be not less than quarterly.

A detailed description of the ratio and its components can be found in the document ‘Basel III: International framework for liquidity risk measurement, standards and monitoring’, published in December 2010, that can be accessed at www.bis.org

- The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) is designed to improve the short term resilience of the liquidity risk profile of banks. It requires banks to hold a buffer of ‘high quality’ liquid assets to match net liquidity outflows during a 30 day period of stress. In other words, the ratio shows if the bank can survive an acute stress scenario lasting for a month.

- Additional requirement for Systemically important financial institutions (SIFI)10:

The financial crisis of 2007 saw the fall or impairment of large, global institutions. The contagion that ensued affected global financial stability. The public sector intervention in many countries to restore financial stability imposed huge financial and economic costs, and also increased the moral hazard associated with too-big-to-fail institutions (by encouraging risky behaviour).

Basel III seeks to mitigate this externality by identifying global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and global systemically important financial institutions (G-SIFIs), and mandating them to maintain a higher level of capital based on their importance in the global financial system. The Basel committee’s approach is based on the Financial Stability Board’s document endorsed by the G20 leaders in November 201011.

For assessing which banks should be considered as G-SIB, an indicator based measurement approach was adopted. The selected indicators reflect the size of banks, their interconnectedness, the lack of readily available substitutes or financial institution infrastructure for the services they provide, their global (crossjurisdictional) activity and their complexity. The indicator-based measurement approach would be supported by supervisory judgment based on certain principles. The BCBS also identified several ancillary indicators which can support the supervisory judgment.

The Basel Committee grouped G-SIBs into different categories of systemic importance based on the score produced by the indicator-based measurement approach. GSIBs would be initially allocated into four buckets based on their scores of systemic importance, with varying levels of additional loss absorbency requirements applied to the different buckets as set out in Table 11.7.

TABLE 11.7 MAGNITUDE OF ADDITIONAL LOSS ABSORBENCY FOR G-SIBS

Source: BCBS, 2011, Global systemically important banks: assessment methodology and the additional loss absorbency requirement-Rules text, November 2011, page 15

Source: BCBS, 2011, Global systemically important banks: assessment methodology and the additional loss absorbency requirement-Rules text, November 2011, page 15The additional loss absorbency requirement is to be met with Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital. The requirements are only the minimum prescribed levels of capital required. The list of G-SIBs would be reviewed annually.

These requirementsare to be phased-in in parallel with the capital conservation and countercyclical buffers, i.e., between 1 January 2016 and year end 2018, becoming fully effective on 1 January 2019.

- Enhancing risk coverage:

In addition to raising the quality and level of the capital base, the Basel Committee has taken cognisance of other material risks that could impact capital. Failure to capture major on and off-balance sheet risks, as well as derivative related exposures, was a key factor that amplified the financial crisis of 2007.Based on the lessons learned from the crisis, revised metrics have been proposed in the Basel III document.

We know that total capital requirements are calculated relative to risk weighted assets. Under Basel III, the enhanced risk coverage in relation to capital market instruments and activities, could result in an increase in risk weighted assets. Further, Basel III addressed some concerns about the reliance on external credit ratings while determining risk weights, especially after the criticism that external credit rating agencies invited for their perceived role in the financial crisis.

- Higher capital requirements for trading and securitization activities—In July 2009, the Basel Committee announced, among other things, higher capital requirements for trading and securitization activities under Basel II (also called Basel 2.5).The trading book12 reforms, among other things, introduced new risk weights to better capture risks in trading portfolios. The securitization reforms also included an increase in the risk-weighting of certain securitizations and resecuritization exposures.

- Capital requirements for certain counter party credit risk exposures—Basel III has enhanced capital requirements and risk management standards for counter party credit risk exposures arising from derivatives, repos and securities financing activities. It includes an additional capital charge for possible losses due to the deterioration in the creditworthiness of counter parties or increased risk weights on exposures to large financial institutions. The objectives were to reduce the risk of transmission of shocks between financial institutions whilst also creating incentives to move Over The Counter (OTC) derivative exposures to central counter parties and exchanges. The measures include additional capital requirements based on the following measures:

- Effective Expected Positive Exposure (EEPE), through the use of stressed inputs

- Credit Value Adjustment (CVA), that accounts for mark to market losses due to deterioration in the creditworthiness of counter parties

- Specific ‘wrong way risk’ if future exposures to a specific counter party is highly positively correlated with the counter party’s probability of default

- External credit ratings in the Basel III framework—Basel III has incorporated elements of the International Organization of Securities Commissions’ (IOSCO) Code of Fundamentals for Credit Rating Agencies that requires banks to carry out internal assessments of externally rated securitization exposures.

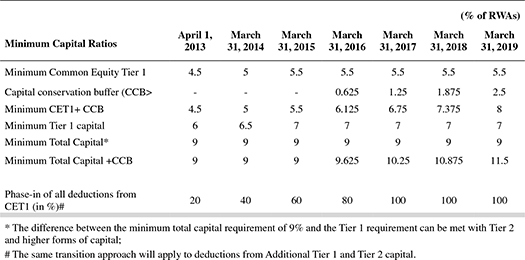

Table 11.8 shows the phase in arrangements for banks to completely adopt Basel III

TABLE 11.8 TIMELINES FOR MIGRATION TO BASEL III

Annexure I provides an overview of the determination of risk weighted assets under existing select approaches of the Basel norms. The revisions to these approaches and standards are being briefly described in the paragraphs given below.

Annexure II to this chapter is a case study on why Basel II Accord takes a share of the blame for the financial crisis of 2007.

BASEL IV –OR IS IT BASEL 3.5? MOVE TO MORE REGULATORY APPROACHES TO RISK MEASUREMENT

We have seen that Basel III focuses on enhancing the stability of the financial system by increasing both the quantity and quality of regulatory capital, and liquidity. Figure 11.3 shows the evolution of Basel regulations, in which Basel III has addressed strengthening of bank capital, the numerator of the Capital Adequacy ratio. Basel III did not make many changes in the denominator of the ratio, which comprise the Risk Weighted Assets (RWA).

After Basel III went into effect, the BCBS began revisiting the transparency and consistency in risk measurements across approaches, jurisdictions and banks. The proposals and consultative documents that have been issued since 2014, are being termed as a move to ‘Basel IV’.

The series of regulatory measures proposed are as follows. It is noteworthy that all the measures are aimed at reinforcing the measurement of RWA – the denominator of the Capital Adequacy Ratio – which essentially comprises of Credit Risk, Market Risk and Operational Risk.

1. Market Risk Requirements – Fundamental Review Of Trading Book (FRTB)*

In the previous chapter we had learnt the salient features of the treatment of market risk in the above mentioned documents.

The key features of the revised framework include the following:

- A revised boundary between the trading book and banking book.

- A revised internal models approach for market risk.

- A revised standardised approach for market risk.

- A shift from value-at-risk to an expected shortfall measure of risk under stress.

- Incorporation of the risk of market illiquidity.

The revised framework comes into effect from January 2019, with banks reporting from the end of 2019. There are significant changes compared with the post crisis Basel 2.5 market risk requirements. Some examples are given below.

Trading book requirements (see end note 12 for a brief description of trading and banking books). There has been a substantial tightening in the banking book/ trading book boundary with the objective of reducing the scope of regulatory arbitrage, such as constraints on the movement of instruments across books, and a fixed addition to capital required if such movements caused any reduction in capital to the bank. The rules also specify that certain instruments should be assigned to the banking book, such as unlisted equities, real estate holdings, instruments being intended for securitization, retail and SME credit.

Internal models for market risk measurement: Banks wishing to use internal models have to go through a number of steps, such as (a) qualitative and quantitative assessment of the model by the supervisor; (b) post approval nomination of specific trading desks that fall within the ambit of the model (those trading desks out of the scope of the model that will have to calculate capital requirements using the revised standardized approach); (c) where internal models are approved, demonstration of existence of sufficient real data points; (d) approved models can use the Expected Shortfall (ES) to estimate capital risk charge, along with an additional default risk charge add on. Models not passing the test at any step, would use the standardized approach. The capital multiplier applicable to the internal model is 1.5, which will be applied to the ES component.

Revised standardized approach: The revised standardized approach is complex, requiring calculation of risk sensitivities. Additionally, the approach specifies inclusion of a standardized default charge (as for credit risk), and a residual risk add-on to capture other risks.

In most cases, it is expected that the capital requirement for market risk will increase due to the revised rules.

2. Counterparty Credit Risk

The Standardized approach for Counterparty credit risk was published in March 2-14.13

Counterparty credit risk (CCR) is the risk associated with uncertain future exposure on derivatives and repo like transactions. Basel III had introduced a Credit Valuation Adjustment (CVA) charge (the concept of CVA has been briefly described in the chapter on Credit Risk). The Basel III requirements have been further revised in tune with the FRTB.

The new Standardized Approach (SA-CCR), finalized in March 2014, is applicable to all derivative contracts (excluding repo like contracts) from January 2017. The approach plays a significant role in calculation of large exposures of capital requirements (CCR and CVA) and the leverage ratio of banks. It is also expected to indirectly impact capital held by banks who are also clearing house members.

The CVA treatment is also being reviewed and updated proposals for change in line with FRTB are expected.

3. Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book (IRRBB)

The revised standards were published in April 201614

The standards revise the Committee’s 2004 Principles for the management and supervision of interest rate risk, which set out supervisory expectations for banks’ identification, measurement, monitoring and control of IRRBB as well as its supervision. The key enhancements to the 2004 Principles include:

- More extensive guidance on the expectations for a bank’s IRRBB management process in areas such as the development of interest rate shock scenarios, as well as key behavioural and modelling assumptions to be considered by banks in their measurement of IRRBB.

- Enhanced disclosure requirements to promote greater consistency, transparency and comparability in the measurement and management of IRRBB. This includes quantitative disclosure requirements based on common interest rate shock scenarios.

- An updated standardised framework, which supervisors could mandate their banks to follow or banks could choose to adopt.

- A stricter threshold for identifying outlier banks, which is has been reduced from 20% of a bank’s total capital to 15% of a bank’s Tier 1 capital.

The standards reflect changes in market and supervisory practices since the Principles were first published in 2004, which is particularly pertinent in light of the current exceptionally low interest rates in many jurisdictions. The revised standards, which were published for consultation in June 2015, are expected to be implemented by 2018.

4. Credit Risk – Revisions to Standardized Approach and IRB Approach, and the Revisions to the Securitizations Framework

The committee has been considering two methodologies – a more credible standardized approach for credit risk, and how the Internal Ratings Based (IRB) approach should be adjusted for better simplicity and comparability.

The second consultative document (December 2015) on Revisions to the Standardised Approach for credit risk15 forms part of the Committee’s broader review of the capital framework to balance simplicity and risk sensitivity, and to promote comparability by reducing variability in risk-weighted assets across banks and jurisdictions.

Some salient features proposed in the above document include (a) a two stage process for exposure to banks, with unrated exposures subject to a new approach; (b) a refined approach for corporate exposures, with and without external ratings; (c) 85% risk weight for SME exposures; (d) issue specific external ratings for specialized lending, and specific risk weights where external ratings are not available or not permitted; (e) specific detailed processes for risk weighting loans to real estate. The document does not set out a standardized approach for sovereigns and other public sector entities, or which categories are being considered under a broader review of these exposures, including the IRB.

The consultative document (March 2016) Reducing variation in credit risk-weighted assets constraints on the use of internal model approaches16 sets out the Committee’s proposed changes to the advanced internal ratings-based approach and the foundation internal ratings-based approach.

The proposed changes to the IRB approaches set out in the above consultative document include a number of complementary measures that aim to: (i) reduce the complexity of the regulatory framework and improve comparability; and (ii) address excessive variability in the capital requirements for credit risk. Specifically, the Basel Committee proposes as follows:

- Remove the option to use the IRB approaches for certain exposures, where it is judged that the model parameters cannot be estimated sufficiently reliably for regulatory capital purposes (section 2);

- Adopt exposure-level, model-parameter floors to ensure a minimum level of conservatism for portfolios where the IRB approaches remain available (section 3); and

- Provide greater specification of parameter estimation practices to reduce variability in risk weighted assets (RWA) for portfolios where the IRB approaches remain available (section 4).

Final rules are awaited for the above mentioned proposals for credit risk measurement.

Securitization Exposures – final Standards

Final standards have been published in respect of securitization exposures in July 2016. The document titled Revisions to the Securitization Framework17 states that the standards have been “amended to include the alternative capital treatment for “simple, transparent and comparable” securitisations”.

The revised framework comes into effect in January 2018.

The financial crisis highlighted weaknesses in the Basel II securitization framework, some of which were identified as the following:

- Very low risk weights for highly rated securitization exposures.

- Mechanistic reliance on external ratings.

- Very high risk weights for low rated senior securitization exposures.

- Cliff effects.

- Insufficient risk sensitivity of the framework.

The revised framework aimed at addressing the major shortcomings of the earlier one. Some of the revisions relate to the following aspects:

(a.) Hierarchy

The Basel II framework consists of two hierarchies – one for the Standardized Approach (SA), and the other for the Internal Ratings Based approach (IRB) – depending on the approach used by banks for the underlying assets securitised. The Basel III revised framework has revised this hierarchy to reduce reliance on external ratings and to simplify and limit the number of approaches. Diagram 11.4 shows the revised hierarchy under the revised framework.

The revised hierarchy of approaches in the revised framework for securitisation exposures is:

DIAGRAM 11.4 REVISED HIERARCHY OF APPROACHES UNDER THE REVISED SECURITIZATION FRAMEWORK

(b.) Approaches

The number of approaches have also been reduced in the revised framework. There would be only three primary approaches, as opposed to the multiple approaches and exceptional treatments of the Basel II framework. The revised hierarchy of approaches relies on the information that is available to the bank and on the type of analysis and estimations that it can perform on a specific transaction.

The STC criteria are intended to help transaction parties – including originators, investors and other parties with a fiduciary responsibility – evaluate more thoroughly the risks and returns of a particular securitisation, and to enable more straightforward comparison across securitisation products within an asset class. These criterias should assist investors in undertaking their due diligence on securitisations.

| What does STC mean? | |

|---|---|

| Simplicity | Simplicity refers to the homogeneity of underlying assets with simple characteristics, and a transaction structure that is not overly complex. |

| Transparency | Criteria for transparency to provide investors with sufficient information on the underlying assets, the structure of the transaction and the parties involved in the transaction, thereby promoting a more comprehensive and thorough understanding of the risks involved. The manner in which the information is available should not hinder transparency, but instead support investors in their assessment. |

| Comparability | Criteria promoting comparability which could assist investors in their understanding of such investments and enable more straightforward comparison across securitisation products within an asset class. More importantly, they should appropriately take into account differences across jurisdictions. |

Banks must deduct from Common Equity Tier 1 any increase in equity capital resulting from a securitisation transaction, such as that associated with expected future margin income resulting in a gain on sale that is recognised in regulatory capital.

The revised framework document quoted above also contains detailed illustrations.

5. Operational Risk

The second consultative document on Standardized Measurement Approach for Operational Risk was released by BCBS in March 2016.18

The committee’s review of banks’ operational risk modelling practices and the resultant capital requirement revealed that the inherent complexity and lack of comparability of Advanced Measurement Approach (AMA) was leading to variability in risk weighted asset calculations. The committee therefore proposes to remove the AMA from the regulatory framework.

The revised operational risk capital framework will be based on a single non model based method, termed as Standardized Measurement Approach (SMA). The SMA would build on the simplicity and comparability of the standardized approach and embody the risk sensitivity of an advanced approach. It would mainly consist of a revised business indicator, new size-based risk coefficients instead of segment-based risk coefficients, and a loss component that accounts for observed operational losses.

The final rules are awaited.

Capital floors

In December 2014, BCBS published a consultative document Capital Floors: The Design of a Framework Based on Standardised Approaches.19

This framework will replace the current transitional floor, which is based on the Basel I Standard 1. The revised capital floor framework will be based on the Basel II/III standardised approaches, and allows for a more coherent and integrated capital framework.

The objectives of a capital floor are to: ensure that the level of capital across the banking system does not fall below a certain level; mitigate model risk and measurement error stemming from internally modelled approaches; address incentive-compatibility issues; and enhance the comparability of capital outcomes across banks. A capital floor complements the leverage ratio introduced as part of Basel III. Together, these measures aim to reinforce the risk-weighted capital framework and promote confidence in the regulatory capital framework.

The final rules are awaited.

7. Pillar 3 Disclosure Requirements – Consolidated and Enhanced framework

Pillar 3 of Basel III has been revised and enhanced in March 2017, through Pillar 3 Disclosure Requirements - Consolidated and Enhanced Framework20

We have seen earlier in this chapter that the Pillar 3 disclosure framework seeks to promote market discipline through regulatory disclosure requirements. The enhancements in the revised framework contain three main elements:

- Consolidation of all existing Basel Committee disclosure requirements into the Pillar 3 framework, covering the composition of capital, the leverage ratio, the liquidity ratios, the indicators for determining globally systemically important banks, the countercyclical capital buffer, interest rate risk in the banking book and remuneration.

- Introduction of a “dashboard” of banks’ key prudential metrics which will provide users of Pillar 3 data with an overview of a bank’s prudential position and a new disclosure requirement for banks which record prudent valuation adjustments to provide users with a granular breakdown of its calculation.

- Updates to reflect ongoing reforms to the regulatory framework, such as the total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) regime for a global systemically important banks and the revised market risk framework published by the Committee in January 2016.

The implementation date for each of the disclosure requirements is set out in the standard.

Further regulatory initiatives

a. Risk weighting of Sovereign exposures:

This would entail introduction of regulatory capital requirements for banks investing in governments based solely on external ratings.

b. IFRS 9:

IFRS 9 is intended as replacement of the current accounting standard IAS39 for financial instruments and introduction of a new framework for classification, impairments and hedge accounting. The standards become effective in 2018.

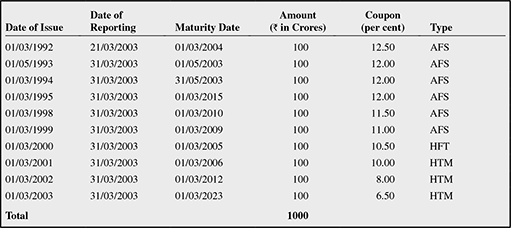

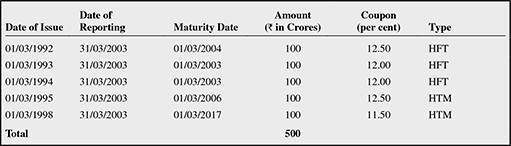

While IAS 39 looks at incurred credit losses, IFRS 9 is intended as a futuristic standard for expected credit losses.