CHAPTER SEVEN

Credit Monitoring, Sickness and Rehabilitation

CHAPTER STRUCTURE

Section II Banks in India—Credit Monitoring and Rehabilitation Process

Annexures I, II, III (Case studies)

KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM THE CHAPTER

- Understand why credit needs to be monitored after disbursal.

- Learn to recognise symptoms of sickness/triggers of financial distress.

- Analyse whether to nurse or not to nurse.

- Understand how rehabilitation packages are framed.

SECTION I

BASIC CONCEPTS

The Need for Credit Review and Monitoring

From the previous chapters, it is evident that ‘credit management’ in a bank consists of two distinct processes—before and after the credit sanction is made. After the credit sanction is made, and the loan is disbursed to the borrower, it is important to ensure that the principal and interest are fully recovered. Loan review is, therefore, a vital post-sanction process.

Loan review helps in the following:

- Continuously checking if the loan policy is being adhered to.

- Identifying problem accounts even at the incipient stage.

- Assessing the bank’s exposure to credit risk.1

- Assessing the bank’s future capital requirements.2

A sound credit review process is necessary for the long-term sustenance of the bank. Once a credit is granted, it is the responsibility of the business unit, along with a credit administration support team, to ensure that the credit limit is being operated well, credit files, financial information and other information are updated periodically and the account is ‘monitored’, to ensure that the debt is serviced on time.

An effective credit monitoring system will have to include measures to ensure the following:

- The bank should periodically obtain and scrutinize the current financial statements of the borrower.

- Systems should be in place to ensure that covenants are complied with, and any violation is immediately noticed.

- The system should periodically ensure that the security coverage for the advances granted is not diluted.

- Payment defaults under the loan contract should be immediately noticed.

- Loans with the potential to run into problems should be classified in time to institute remedial action.

While individual borrowers should be subjected to intense monitoring, banks also need to put in place a system for monitoring the overall composition and quality of the credit portfolio.

It is seen that many problem credits reveal basic weaknesses in the credit granting and monitoring processes. A strong internal credit control process can, in many cases, offset the shortcomings in external factors such as the economy or the specific industry. It also follows that the monitoring policy need not be uniform, and can instead provide more frequent reviews and financial updates for riskier clients. Thus, rather than dedicating equal time to all credit transactions, review and monitoring time could be allocated to high risk and/or very large loans.

The structure of the credit review process would have to periodically examine the assumptions on which every loan was appraised and granted, and whether these assumptions have changed materially enough to endanger the debt-servicing capacity of the borrower. Typically, all or most of the following aspects are reviewed for every loan till it is repaid in full.

- Developments in the economy that may have an impact on the industry in which the borrower operates.

- Developments in the industry or sector in which the borrower operates.

- The borrower’s financial health. Is the credit adequate? Has the borrower over-or under-borrowed? Can the borrower sustain debt service without default?

- The borrower’s payment record in this and other loans so far.

- The quality, condition and value of the prime and collateral securities.

- The completeness of loan documentation, and developments in law governing the instruments effecting credit delivery.

- Adherence to loan covenants. Is there a danger of violating one or more of these? How critical are these violations for the debt service and the long-term relationship with the borrower?

Some borrowers may default on debt service due to factors out of their control. In such cases, the bank may have to reschedule the debt service requirements and alter some of the covenants, if necessary.

Central banks of most countries have devised country-specific definitions and control systems to tackle ‘sick’ borrowers. There are three categories of sickness that could afflict borrowers.

- Sickness at birth—the project itself has become infeasible either due to faulty assumptions or a change in environment.

- Induced sickness—caused by management incompetencies or willful default.

- Genuine sickness—where the circumstances leading to sickness are beyond the borrowers’ control, and has happened in spite of the borrowers’ sincere efforts to avert the situation.

When the borrower turns ‘sick’, the bank will have to investigate (a) the reasons for sickness, and whether remedial measures can revive the ailing firm; (b) the rationale for categorizing the borrower as ‘sick’; (c) the risks involved in rehabilitating the borrowing firm and (d) in case the bank decides to rehabilitate, the requirements for such revival in the form of additional financing, government support, management inputs or upgraded technology.

Triggers of Financial Distress

When does a firm face financial distress? Financial failure occurs when there is a prolonged period of lack of profitability. The most marked among the manifestations of lack of profitability is the decay in the cash inflows. Due to this decay, even though the firm’s balance sheet could show a healthy level of current and fixed assets, the firm would be unable to meet its current liabilities. An example of such a situation is when the firm has a high level of receivables, but these are not realizable. Or, inventories look high but the quality is poor and items are non-moving, and due to low profitability the firm does not write them off. Or, due to continuous losses, the firm does not provide adequate depreciation, and the fixed asset balances seem high. In fact, in these cases, the assets are rapidly losing market value, which is not reflected in the balance sheet. Thus, a situation finally arises when the firm’s assets are not all realizable, the cash flows are thinning out, and revenues have not been covering expenses over a period of time. If such a state prolongs, economic failure could occur—the rates of return from investments drop below the cost of capital (COC), and the market value of liabilities exceeds the market value of assets. The result is ‘insolvency’.

There are several factors that lead to financial distress in firms. Any of the risk factors listed in Annexure I of Chapter 5 could turn a reality, and cause a firm to fail. The factors could range from fundamental changes in the way firms do business, to sweeping changes in the economy, industry and markets. The reasons could also be endogenous to the firm, such as loss of major contracts or customers, growth without adequate capital, superior competition, management incompetence or poor financial management.

Lending banks would, therefore, be concerned with tackling the following crucial issues:

- What are the signals of financial distress?

- Can banks detect signs of distress early enough, and initiate remedial action, so that bank funds do not turn irrecoverable?

- Can financial failure be predicted?

Financial Distress Models—The Altman’s Z-Score

Typically, the statistical tools used to predict financial distress are regression and discriminant analysis. Regression analysis uses past data to forecast values of dependent variables. Discriminant analysis classifies data into predetermined groups by generating an index. The model most popular with bankers and analysts, apart from ad hoc models, is the Altman’s3 Z-score model. Since it has been thoroughly tested and widely accepted, the model scores over various others that have been subsequently developed and used for predicting bankruptcy.3

The discriminant function Z was found to be:

where X1 = working capital/total assets (%)

X2 = retained earnings/total assets (%)

X3 = EBIT/total assets (%)

X4 = market value of equity/book value of debt (%)

X5 = sales to total assets (times)

The firm is classified as ‘financially sound’ if Z > 2.99 and ‘financially distressed’ or ‘bankrupt’ if Z < 1.81.

What are the model’s attributes that lead to its continued validity in most cases? The model is based on two important concepts of corporate finance—operating leverage and asset utilization. A high degree of operating leverage implies that a small change in sales results in a relatively large change in net operating income. Lenders are aware of the pitfalls of financing firms with high operating leverage—they should be convinced that the borrowers can withstand recessions or sudden dips in sales. Asset utilization suffers when too many assets are held on the firm’s balance sheet, disproportionate to the operating requirements and the sales generated. It is noteworthy that the model has total assets as the denominator in four out of the five variables. Box 7.1 on the next page provides a connective insight into the variables constituting the model.

However, the Z-score model makes two basic assumptions. One, that the firm’s equity is publicly traded and second, that it is a firm engaged in manufacturing activities.

Hence, it became necessary to look for alternate models that predict financial distress in non-manufacturing or emerging market settings.

Some Alternate Models Predicting Financial Distress

The following are some alternate models that predict financial distress:

- The ZETA score4 enables banks to appraise the risks involved in firms outside the manufacturing sector. The score is reported to provide warning signals 3–5 years prior to bankruptcy (against 2 years for Z score). It considers variables such as (a) return on assets (ROA), (b) earnings stability, (c) debt service, (d) cumulative profitability, (e) current ratio, (f) capitalization, and (g) size of the business as indicated by total tangible assets. An increase in the score is a positive signal.5

- Often, in emerging economies, it is not possible to build a model based on a sample from that country because of the lack of credit experience there. To deal with this problem, Altman, Hartzell and Peck (1995) have modified the original Altman’s Z-score model to create the Emerging Market Scoring (EMS) model.6 One such EMS model is the Emerging Markets Corporate Bonds Scoring System.7 The model can be applied to both manufacturing and non-manufacturing companies, as well as privately held and publicly owned firms. In this case, an EM score is first developed as being equal to 6.56X1 + 3.26X2 + 6.72X3 + 1.05X4 + 3.25, where +X1 is defined as working the capital/total assets, +X2 is defined as retained earnings/total assets, +X3 is defined as operating income/total assets and +X4 is defined as the book value of equity/total liabilities. The EM score is modified based on critical factors such as the firm’s vulnerability to currency devaluation, its industry environment, and its competitive position in the industry. The resulting analyst modified rating is compared with the actual bond rating, if any, and other special features such as high quality collateral or guarantees, the sovereign rating, etc. should be factored in.

BOX 7.1 THE ALTMAN’S Z-SCORE MODEL—SIGNIFICANCE OF INDICATORS

Assume, e.g., a firm with a high operating leverage.

- When sales decline, sales/assets also declines. Because of the high operating leverage, earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) falls, leading to a fall in the EBIT/assets ratio.

- When EBIT falls, it drives down the retained earnings, and, thus, the ratio of retained earning/total assets.

- A fall in retained earnings is linked to the working capital and, therefore, the working capital/total assets fall.

- The market does not perceive the declines in key ratios in a favourable light, and the market value of equity falls. The book value of debt remaining relatively unchanged, the ratio market value of equity/book value of debt decreases.

- The decline in market value of equity causes a dip in the firm value and an increase in the financial leverage of the firm. This implies higher financial risk to the firm, and, hence, a higher probability of distress.

- The above chain of events is encapsulated in a decline in the Z score.

- Influenced by the use of discriminant analysis in Altman’s model, subsequent researchers used logit analysis, probit analysis and linear probability models to improve the accuracy of predicting distress.8

- The multinomial logit technique has been used to build models to distinguish between financially distressed firms that survive and financially distressed firms that ultimately go bankrupt.

- Other researchers have proposed a ‘gambler’s ruin’ approach to predict bankruptcies. This approach combines the net liquidation value (total asset liquidation value less total liabilities) with the net cash flows (cash inflows less cash outflows). Other things being equal, the model predicts that the lower the net liquidation value, the smaller the net cash flows, and the higher the volatility of these cash flows, the higher would be the probability of firm failure.9

- Neural networks10 are also increasingly being used in predicting financial distress.

- From the early 2000s, some other models in bankruptcy prediction are reported to have shown good performance. An example is a hybrid model combining ‘genetic programming and rough sets’, the approach taken in a 2002 paper by McKee and Lensberg11. Another approach is the Multidimensional scaling approach proposed in a 2001 paper by Mar–Molinero and Serrano–Cinca12, reported to bypass the shortcomings of models based on discriminant analysis, logit techniques or neural network models.

- More recently, studies13 have found Classification and Regression Trees (CART), which is an important tool in analytics and data mining, to be superior to discriminant analysis. These studies mostly support decision trees as being superior to discriminant and logit analysis. In 2008, Survival analysis techniques were used to study the influential factors in the survival of specific classes of businesses, such as Internet – based businesses14

An illustrative list of warning signs that banks should look out for is provided in Annexure I.

The Workout Function

A loan is considered ‘impaired’ if, based on the current situation, it appears probable that the bank will be unable to collect all the amount due (both prinicipal and interest) from the borrower, in accordance with the terms of the loan agreement. The purpose of credit review and monitoring is to watch out for warning signals, identify ‘troubled’ or ‘sick’ loans, document the findings, revise credit ratings, if necessary, and, finally, classify the credit exposures under the appropriate categories for purpose of making ‘provisions’ against expected losses.15

The aims of establishing a separate workout function are primarily to examine whether the credit granted is performing as expected and, if not performing according to expectations, classify problem credits appropriately, and, second, to explore possible solutions to resolve the problem. Generally, banks have two choices for the workout—restructure the problem loan or liquidate it.

The skills, procedures and processes necessary for running a workout organization are fundamentally different from those relevant to credit appraisal, sanction and monitoring. The problem loans are classified into appropriate risk categories, and the workout procedure is decided. Though the line banker knows the problem credit better, the loan workout department is constituted with better expertise and experience in solving credit problems. Banks without a separate workout function could see a rise in credit defaults. If this happens, the quality of credit origination and appraisal could also slacken.

An independent workout function must do well the following four things16:

- It should establish clear rules for using a traditional workout process. Sometimes, a lower-cost, streamlined collection process via letters and phone calls would be sufficient to rectify the default. Successful banks may have four or five separate processes, depending on cost and potential for collection.

- It should prioritize loan workout effort according to the urgency of the situation, the possible economic impact and the probability of success in order to achieve high recovery rates. While it is necessary for loan workout to be reactive to day-to-day crises, it is also equally important to set clear priorities based on bottom-line impact.

- The loan workout function should assemble the best skills. Each situation will require a specific skill or combination of skills, such as real estate, legal, credit assessment, financial analysis, merchant banking, collateral evaluation and basic project management among them. The bank’s systems should allow for flexibility to build an appropriate team from internal or external resources.

- The loan workout should assess available alternatives using analytically driven decision rules. The basic choices facing a bank—restructuring, loan sales, foreclosures, or ‘do nothing’—should be evaluated according to the net present value (NPV) of each option multiplied by its probability of success. Such analyses should take into account all costs, including operating and carrying costs, as well as ROA (if any).

Banks often centralize the workout function to ensure that state-of-the-art methodologies are used to monitor overall risk response, and to create an environment to improve decision making without diffusing accountability. A well-designed central authority can provide maintenance and monitoring of limit systems and portfolio concentration; an early warning system authorized to place clients on the watch list; industry and micro-economic analysis to identify optimal portfolio composition and secondary market evaluation and trading capability.

The workout officers examine the updated credit file, and meet with the borrower to explore if the ‘impaired’ credit can be revived and the firm rehabilitated. If the firm’s operations could be made viable after restructuring, the loan will be restructured with modified terms and some ‘sacrifices’ on the part of the bank.

SECTION II

CREDIT INfORMATION COMPANIES IN INDIA 17

We have understood the importance of building credit files (credit information on borrowers) from Chapter 6. It is not uncommon for a single borrower to required different types of credit facilities from various branches of the same branch, nor is it uncommon for borrowers/customers to bank with multiple banks. We have also seen earlier that a key deciding factor for banks to grant loans is the integrity of the borrower, which can be interpreted from the borrower’s track record of borrowings and timely repayments. Conversely, lack of credit history is an impediment to smooth credit flow, since inadequate information could lead to misleading conclusions about a borrower’s creditworthiness or the pricing of a loan to such a borrower. In the absence of an industry-wide common information system, appraising a borrower’s creditworthiness could be a subjective exercise.

In recognition of the vital need for credit information across the industry, a scheme for disclosure of information regarding defaulting borrowers of banks and financial institutions was introduced in 1994. In order to facilitate sharing of credit and borrower related information, the Credit Information Bureau (India) Limited (CIBIL) was set up in 2000, which took over the functions of dissemination of information relating to defaulting borrowers from the RBI. The Credit Information Companies (Regulation) Act was enacted in 2005 to facilitate the setting up of credit information companies.

The Government and the RBI have framed rules and regulations for implementation of the Act, with specific provisions for protecting individual borrower’s rights and obligations. The rules and regulations were notified on December 14, 2006 in terms of the provisions of the Act.

Credit Information Companies (CIC) help lenders assess creditworthiness of individual borrowers and their ability to pay back loans, by collating data on the borrower’s track record of timely repayment of loans and other forms of credit availed of. They collect personal financial data from financial institutions and others, which helps in modelling price discrimination, taking into account the individual borrower’s credit rating and past behaviour. The information is aggregated and made available on request to companies/banks which have shared the data, for the purpose of credit assessment and credit scoring. The credit history of a borrower spans all the financial institutions the borrower has dealt with in the past, which helps the bank seeking the information to speed up credit decisions. CIBIL, for instance, collects (monthly), collates and disseminates credit information pertaining to both commercial and consumer borrowers to a closed group of member banks, financial institutions, non banking finance companies, housing finance companies and credit card companies. Data sharing is reciprocal, which implies that only members who have shared credit data are eligible to access credit information reports from CIBIL.

CIBIL and Loan Approval

CIBIL’s products, especially the CIBIL Trans Union Score and the Credit Information Report (CIR) are important to the loan approval process in banks. The credit score helps banks quickly determine, who they would like to evaluate further to provide credit. The CIBIL Trans Union Score ranges from 300 to 900. CIBIL data indicates that loan providers prefer a credit scores which are greater than 700.

Once the bank decides which set of loan applicants to evaluate, it analyzes the CIR in order to determine the applicant’s eligibility. Eligibility basically means the applicants ability to take additional debt and repay additional outflows given their current commitments.

Post completion of these first 2 steps the bank requests other relevant documents from the borrower in order to finally sanction the loan.

Other Credit Information Companies in India

The banks and the financial institutions can submit details of wilful defaulters, borrowers on whom suits have been filed for recovery and other default data to a credit information company, which has obtained certificate of registration from RBI in terms of Section 5 of the Credit Information Companies (Regulation) Act, 2005 and of which the bank is a member. The following companies have been recognized by RBI and CICs and certificates of registration have been granted;

- Credit Information Bureau (India) Ltd. (www.cibil.com)

- Experian Credit Information company of India Pvt. Ltd. (www.experian.in)

- Equifax Credit Information Services Pvt. Ltd. (www.equifax.co.in)

- High Mark Credit Information Services Pvt. Ltd. (www.highmark.in)

DEBT RESTRUCTURING AND REHABILITATION Of SICK fIRMS IN INDIA—THE WORKOUT fUNCTION

Source: RBI Master circular titled ‘Prudential norms on income recognition, asset classification and provisioning pertaining to advances” dated July 1, 2015, and various relevant RBI guidelines and circulars.

Companies on the verge of liquidation had to seek protection under the Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985, administered by the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR). As of 2001, debt restructuring in India could be achieved through one of two modes—contractual, or court-based. Neither the contractual restructuring nor the court-based restructuring automatically insulated the company against suits or other action by creditors. Thus, BIFR though aimed at rehabilitating industrial enterprises, failed to achieve its objective. Moreover, it did not help banks and the financial institutions to recover their debts.

The process of workout of troubled loans—restructuring and rehabilitation—has been revamped since 2003. We will see how the process operates in Annexure II. The Basel Committee calls this process of restructuring as “forbearance”.

Box 7.2 provides an illustrative list of warning signals of incipient sickness.

BOX 7.2 AN ILLUSTRATIVE LIST OF WARNING SIGNALS OF INCIPIENT SICKNESS

- Continuous irregularities in cash credit/overdraft accounts—inability to maintain stipulated margin on continuous basis, or funds drawn from the account frequently exceeding sanctioned limits, or periodical interest debited remaining unrealized;

- Outstanding balance in cash credit account remaining continuously at the maximum;

- Failure to make timely payment of installments of principal and interest on term loans;

- Complaints from suppliers of raw materials, water, power, etc., about non-payment of bills;

- Non-submission or undue delay in submission or submission of incorrect stock statements and other control statements;

- Attempts to divert sale proceeds through accounts with other banks;

- Downward trend in credit summations;

- Frequent return of cheques or bills;

- Steep decline in production figures;

- Downward trends in sales and fall in profits;

- Rising level of inventories, which may include large proportion of slow or non-moving items;

- Larger and longer outstanding in receivables;

- Longer period of credit allowed on sale documents negotiated through the bank and frequent return by the customers of the same; also allowing large discount on sales;

- Failure to pay statutory liabilities;

- Diversion of bank funds for purposes other than running the firm;

- Not furnishing the required information/data on operations in time and non-coperation or discrepancies noticed during routine stock and other inspections by the bank.

- Unreasonable/wide variations in sales/receivables levels.

- Delay in meeting commitments towards payments of installments due, crystallized liabilities under LC/BGs, etc.

- Diverting/routing of receivables through non-lending banks.

The bank office familiar with the day-to-day operations in the accounts exhibiting any of the above symptoms should be able to grasp the significance of these warning signals and initiate timely corrective measures. Such measures may include providing timely financial assistance based on the assessed need, and seeking help from the workout specialists at designated offices of the bank.

What is Restructuring?

As part of their workout function for troubled loans, banks grant concessions on credit facilities granted to borrowers facing financial difficulty due to economic or legal reasons. These are concessions, which banks would otherwise not consideron the credit facilities granted to borrowers. Under such circumstances, the borrower’s account that is under the workout, is termed a ‘restructured account’.

Restructuring would normally involve modification of terms of the advances/securities, which would generally include, among others, alteration of repayment period/repayable amount/the amount of installments/rate of interest (due to reasons other than competitive reasons). (However, extension in repayment tenor of a floating rate loan on reset of interest rate, so as to keep the EMI unchanged provided it is applied to a class of accounts uniformly will not render the account to be classified as ‘Restructured account’. In other words, extension or deferment of EMIs to individual borrowers as against to an entire class, would render the accounts to be classified as ‘restructured accounts’.)

RBI guidelines for restructuring fall under the following broad categories:

- Restructuring of advances to industrial units.

- Restructuring of advances to industrial units under the Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR) mechanism.

- Restructuring of advances to Small and Medium Enterprises (SME).

- Restructuring of all other advances.

It can be seen that in the above categories of guidelines, the differentiation is based on whether a borrower is involved in industrial or non industrial activity. The institutional mechanism for accounts restructured under CDR (for both industrial and non industrial borrowers) has been made specific and elaborate. The Strategic Debt Restructuring Scheme has been introduced to give more powers to the bankers in resolving issues of non payment by borrowers.

Criteria for Considering Restructuring

All eligible advances/borrowing accounts classified under various asset classification categories—such as ‘standard’, ‘sub standard’ and ‘doubtful’ – can be restructured provided they satisfy certain criteria. (For an understanding of the asset classification categories, you may refer to the chapters on ‘Credit risk’)

- The most important criterion for deciding whether to restructure a borrower’s account would be the financial viability after the restructuring package is implemented. The restructuring package should demonstrate reasonable certainty of repayment from the borrower. The viability should be determined by the banks—based on the acceptable viability benchmarks. Box 7.3 contains the viability benchmarks suggested by RBI’s. These benchmarks are indicative and can be modified by banks to suit their unique business requirements. Where an account is not found viable, banks should accelerate the recovery measures.

BOX 7.3 BROAD BENCHMARKS FOR THE VIABILITY PARAMETERS (ILLUSTRATIVE LIST BY RBI—JULY 2015)

- Return on capital employed should be at least equivalent to 5 year government security yield plus 2%.

- The debt service coverage ratio should be greater than 1.25 within the 5 years period in which the unit should become viable and on year to year basis the ratio should be above 1. The normal debt service coverage ratio for 10 years repayment period should be around 1.33.

- The benchmark gap between internal rate of return and cost of capital should be at least 1 per cent.

- Operating and cash break even points should be worked out and they should be comparable with the industry norms.

- Trends of the company based on historical data and future projections should be comparable with the industry. Thus behaviour of past and future EBITDA should be studied and compared with industry average.

- Loan Life Ratio (LLR), as defined below should be 1.4, which would give a cushion of 40 Per cent to the amount of loan to be serviced.

- Banks cannot reschedule/restructure/renegotiate borrowers’ accounts with retrospective effect. While a restructuring proposal is under consideration, the usual asset classification norms (as above) would continue to apply. The asset classification status as on the date of approval of the restructured package would be relevant to decide the asset classification status of the account after restructuring/rescheduling/renegotiation. In case there is undue delay in sanctioning a restructuring package and in the meantime the asset quality of the account deteriorates, it would be a matter of supervisory concern.

- Typically, restructuring entails changes in the prevailing loan agreement. Since the loan agreement is a legal document, changes require a formal process. However, restructuring can be initiated by a bank in deserving cases subject to customer agreeing to the new terms and conditions.

- Borrowers indulging in frauds and malfeasance will not be eligible for restructuring. Where wilful default is suspected, banks may review the account and implement a restructuring package and being satisfied that the borrower is in a position to rectify the wilful default. The restructuring of such cases may be done with Board’s approval, and if restructuring under the CDR Mechanism, the package should be formulated with the approval of the core group only. (Please see Annexure II for an overview of the CDR mechanism)

- Cases under BIFR are not eligible for restructuring without the express approval of BIFR.

Relief Measures under Restructuring

Some typical measures/concessions that are provided to troubled borrowers’ accounts under the restructuring package are as follows:

- A part of the outstanding principal amount can be converted into debt at lower rates or equity instruments as part of restructuring.

- Unpaid interest can be converted into a ‘funded interest term loan’ (FITL) to be repaid in installments under the package.

- The FITL can also be converted into other debt or equity instruments.

- Other relief measures under special circumstances spelt out by RBI. The Strategic Debt Restructuring Scheme (SDR) and the Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A) are measures implemented for deep financial restructuring of large borrowers. These Schemes have been briefly described in Annexure II.

Valuation of Restructured Advances

The restructuring package by banks typically envisages reduction in the rate of interest and/or rescheduling repayment of principal amount. It is evident that these measures will result in diminution in the fair value of the advance. Such diminution in value is an economic loss for the bank and will impact the bank’s market value of equity. It is, therefore, necessary for banks to measure such diminution in the fair value of the advance and make provisions for it by debit to Profit & Loss Account. This provision should be held in addition to the provisions as per existing provisioning norms (Please refer to the chapter on ‘Credit risk’), and in an account distinct from that for normal provisions.

The erosion in the fair value of the advance is computed as the difference between the fair value of the loan before and after restructuring. Fair value of the loan before restructuring will be the present value (PV) of cash flows from interest payments at the existing rate (charged on the advance before restructuring) and the principal repayments, discounted at a rate equal to the bank’s base rate as on the date of restructuring plus the appropriate term premium and credit risk premium for the borrower category on the date of restructuring. Fair value of the loan after restructuring will be computed as the present value of cash flows from interest payments at the revised rate charged on the advance due to restructuring and the principal repayments, discounted at a rate equal to the bank’s base rate as on the date of restructuring plus the appropriate term premium and credit risk premium for the borrower category on the date of restructuring.

The diminution in the fair value should be re-computed on each balance sheet date till the restructured payments are fully paid. The revised annual calculations are meant to capture the changes in the fair value due to changes in the base rate (or discount rate).

The restructuring package should be formulated and implemented within a short time period as stipulated by RBI, so that there is no further erosion in the asset value.

The RBI reiterates in its various guidelines that the basic objective of restructuring is to preserve economic value of units, not ever-greening of problem accounts. This can be achieved by banks and the borrowers only by careful assessment of the viability, quick detection of weaknesses in accounts and a time-bound implementation of restructuring packages.

Information on number and amount of advances restructured, and the amount of diminution in the fair value of the restructured advance should be disclosed in banks’ financial statements (under Notes on Accounts).

Annexure III contains case studies on corporate borrowers whose debts have been restructured under CDR and SDR.

Chapter Summary

- ‘Credit management’ in a bank consists of two distinct processes—before and after the credit sanction is made. A sound credit review process is necessary for the long-term sustenance of the bank. Once a credit is granted, it is the responsibility of the business unit, along with a credit administration support team, to ensure that the credit limit is being operated well. Once the credit is disbursed, credit flies, financial information and other information will have to be updated periodically, and the account ‘monitored’, to ensure that the debt is serviced on time. The monitoring policy need not be uniform, and can instead provide more frequent reviews and financial updates for riskier clients.

- When a borrower turns ‘sick’, the bank will have to investigate (a) the reasons for sickness, and whether remedial measures can revive the ailing firm; (b) the rationale for categorizing the borrower as ‘sick’; (c) the risks involved in rehabilitating the borrowing firm and (d) in case the bank decides to rehabilitate, the requirements for such revival in the form of additional financing, government support, management inputs or upgraded technology.

- It is crucial for lending banks to be able to identify the signals of financial distress, detect them early enough and initiate remedial action, so that bank funds do not turn irrecoverable.

- The model to predict financial distress of firms most popular with bankers and analysts, apart from ad hoc models, is the Altman’s Z-score model. Since it has been thoroughly tested and widely accepted, the model scores over various others that have been subsequently developed and used for predicting bankruptcy.

- The aims of establishing a separate workout function are primarily to examine whether the credit granted is performing as expected and if not performing according to expectations, classify problem credits appropriately, and second, to explore possible solutions to resolve the problem. Generally, banks have two choices for the workout—restructure the problem loan or liquidate it.

- The RBI has proposed various rehabilitation/workout schemes for distressed assets as well as for large corporate borrowers (CDR, SDR and S4A).

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

- Rapid fire questions

Answer ‘True’ or ‘False’

- Loan review helps in checking if loan policy is being adhered to.

- Loan review helps in identifying problem accounts at an advanced stage.

- Loan review helps in assessing the bank’s exposure to credit risk.

- Loan review does not help in assessing bank’s future capital requirements.

- Individual borrowers and the credit portfolio should be monitored regularly by banks.

- Even after granting the loan, the industry in which the borrower operates has to be reviewed periodically.

- A marked decrease in cash flows in a borrowing entity’s business is an indicator of financial distress.

- Altman’s Z score can be used to predict bankruptcy for both publicly traded and privately held companies.

- Altman’s Z score can be used to predict bankruptcy for both manufacturing and non manufacturing companies.

- The workout function in a bank is separated from the credit granting function.

Check your score in Rapid fire questions

- True

- False

- True

- False

- True

- True

- True

- False

- False

- True

- Fill in the blanks with appropriate words and expressions

- The ZETA score enables banks to predict bankruptcy of firms in the ————— sectors.

- Altman’s Z score model uses ————— analysis to predict bankruptcy.

- The Altman’s Z score model classifies a firm as ————— if Z > 2.99.

- The Altman’s Z Score model is based on two important concepts of corporate finance ————— and —————.

- The CIBIL Trans Union score ranges from ————— to —————.

- The most important criterion for banks deciding to restructure borrowers’ accounts would be —————.

- A firm faces financial distress when the market value of its ————— exceeds the market value of its—————.

- The Emerging Markets Corporate Bonds Scoring system can be applied to both ————— and ————— companies.

- Credit Information Companies help lenders assess ————— of individual borrowers.

- Expand the following abbreviations in the context of the Indian financial system

- CIC

- BIFR

- CIBIL

- CDR

- SDR

- FITL

- LLR

- SME

- S4A

- Test your concepts and application

- Define the various money supply measures. What is the rationale for these different measures of money supply?

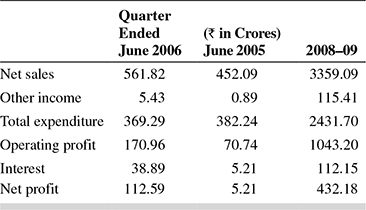

- An over-levered Firm A, financed by Bank X, started making cash losses. Bank X found the firm potentially viable and hence decided to rehabilitate the firm. One year after implementation of the rehabilitation package, the following developments were noticed in the firm’s financial statements.

- Firm A generated quite a large amount of cash in that year

- Total current liabilities of Firm A decreased

- There was a fall in the amount of long-term assets

Give the reasons for the above phenomena

- Why is it a prudent policy to separate credit appraisal and sanctioning from the workout function?

- You are the banker to Firm B and notice the following features of the firm’s cash flows. Explain how each of these observations could endanger the bank’s ability to collect its dues from Firm B.

- The firm has used the money given by your bank for working capital to buy plant and machinery.

- The firm’s COC and ROA is 15 per cent.

- ‘Notes to accounts’ shows considerable exposure to currency and interest rate swaps, to hedge the firm’s export activity.

- ‘Notes to accounts’ shows a large possible write down in asset value, which has not been carried out in the current year.

- The firm’s contingent liabilities are almost equal to the firm’s balance sheet size.

- The firm’s operations also show investments in joint ventures and off balance sheet special-purpose vehicles.

- The firm had taken over a firm in the same line of activity a year ago.

- The firm has certain long-term contract deals for which revenue is getting booked in the current year.

TOPICS FOR FURTHER DISCUSSION

- What is the function of MIS in credit management? What kind of control systems should a bank have to ensure that credit management is done in a proper manner?

- What are the circumstances under which the lender may fail to perform a financial analysis of the borrower? Why is financial analysis so vital to credit management?

- Develop a checklist for credit reviews in a typical bank.

ANNEXURE I

WARNING SIGNS THAT BANKS SHOULD LOOK OUT fOR—AN ILLUSTRATIVE CHECKLIST

Warning Signs Endogenous to the Firm

- Management related

- Lacks technical expertise for the project/running the firm.

- Failure to control costs.

- Poor capacity utilization.

- Improper inventory and receivables management—accumulation of inventory, inefficient collection machinery.

- Inability to anticipate problems and take effective remedial measures.

- Failure to anticipate competition, and loss of competitive edge.

- Diversion of funds, siphoning off funds by management for personal or uses other than for the business.

- Indulging in fraudulent or speculative transactions, such as hoarding of finished goods in anticipation of a price increase, clandestine sale of goods at a premium.

- Disagreements/conflicts among promoters/directors/ managers.

- Improper delegation of duties, or one person dominating decision-making.

- Owners have stake in more than one business, and they no longer take pride in the business the bank has financed.

- Managers’ salaries show sharp reduction.

- Management is unwilling to provide budgets, projects or interim information.

- The owners/managers of the firm do not know the present position the firm is in, and in what direction it has to head in the future.

- Frequent changes in senior management.

- The Board of Directors does not participate effectively.

- Management lacks depth.

- Resignation of key personnel.

- Non-compliance with covenants or excessive negotiation of covenants.

- Management not able to or unwilling to explain unusual off-balance sheet items.

- Visits by the bank to the borrowing firm’s place of business reveals deterioration in the general appearance of the premises.

- Technology related

- Adopting processes that have not been tested on a commercial scale, or requiring major modifications after implementation.

- Choice of obsolete process or technology.

- Wrong choice of technology or collaboration—one that may not be suited to or succeed in the conditions prevailing in the country/state where the firm is located.

- Unsuitable or non-optimal location of the firm.

- Design of plant of an uneconomic size.

- Choice of faulty or unsuitable equipment, without verifying the credentials and capacity of the supplier.

- Production bottlenecks arising from improper balancing of plant and equipment.

- Inadequate maintenance of plant and machinery, leading to frequent breakdowns and production losses.

- Unusually high production wastages.

- Failure to take cognizance of environmental factors while locating the firm.

- Inadequate quality control procedures, leading to product rejections by customers.

- Inappropriate choice of product mix while deciding on plant and machinery.

- Factory operating well below capacity.

- Adoption of obsolete production methods.

- Product related

- Overestimation of demand for products of the firm.

- Orders slowing down in comparison with previous years, and in relation to the orders received by competitors.

- The borrower changes suppliers frequently.

- Inventory to one customer increases.

- Concentration shifts from major well-known customer to one of lesser stature.

- The firm loses an important supplier or customer.

- Demand for product falls.

- Obsolete product distribution methods are still adopted by the firm.

- The firm still supplies to troubled customers and industries.

- The product is priced improperly.

- Increasing sales discounts or sales returns.

- Large orders have been booked at fixed prices under inflationary conditions.

- Ineffective marketing set up.

- Unscrupulous sales and purchase practices.

- Improper launch of new products.

- Overestimation of demand for products, both existing and new.

- Financial management related

- Underestimating project costs at the time of project planning and implementation.

- Inadequate working capital due to diversion of funds or faulty estimation of requirements.

- Inappropriate costing methods for product pricing.

- Financial risk due to high leverage.

- A liberal dividend policy even under adverse circumstances.

- Application of bank funds for purposes other than those for which they were intended.

- Deferring payment of payables and creditors frequently.

- Unusual items appear in the financial statements.

- Negative trends in key indicators such as sales, gross and net profits.

- Slow down in collection of accounts receivables, and increase in the age of debtors.

- Where the owners have multiple businesses, inter-company payables and receivables are not being explained satisfactorily.

- Substantial reduction in cash balances, overdrawn cash balances or uncollected cash during normally liquid periods.

- Inability to avail of trade discounts, either because of poor inventory turnover or the supplier refusing trade discounts.

- Deferred payment of statutory liabilities.

- Creditors are not completely paid out at the end of the working capital cycle.

- Interim results either not provided at all or provided incomplete.

- Late release of financial statements to banks and investors.

- Suppliers cut back favourable terms.

- Accumulation of creditors and debtors, with no satisfactory explanation from the borrower.

- Large and frequent loans are made to or from managers and affiliates.

- The bank overestimates the seasonal peaks and troughs, and lends excessively.

- The firm is unable to repay bank debt from internal generation, and rotates or restructures bank debt for repayment.

- Large customers’ creditworthiness has not been investigated by the firm.

- The firm has over-expanded without adequate working capital.

- Financial controls are weak.

- Excessive investment in fixed assets, not matched by sales and profit growth.

- Sale proceeds from fixed assets and other securities used to fund working capital.

- Sale of a profitable division or product line.

- The firm has not been making deposits in trust funds in time, such as pension and provident funds.

- There are unexplained significant variances in key result areas as compared to the previous years or budget.

- The credit limits are always utilized to the brim, and the firm approaches the bank frequently for ad hoc increases in credit limits.

- Increase in off-balance sheet investments, not adequately explained by the management.

Warning Signs Exogenous to the Firm

- At the project implementation stage

- Currency risk—if the project depends heavily on imported equipment. Adverse changes in exchange rates may result in steep increases in the project cost.

- Upward revision of import duties or excise duties may escalate the project cost.

- Delay in receipt of approvals for the project from the government and other statutory bodies.

- Delay in sanction of term loans from FIs and banks.

- Force major events—acts of God.

- At the production stage

- Non-availability or limited availability of raw material and other inputs.

- Power cuts.

- Transport bottlenecks.

- Delay in supply of critical components by sub-contractors.

- Bottlenecks arising from monsoons and other acts of God.

- Technological innovation may lead to production process becoming obsolete.

- At the sales/marketing stage

- Delay in commissioning downstream projects intended for purchase of project’s output.

- Withdrawal or reduction in the degree of protection by the government.

- Market is saturated since the entry barriers are low and competition is catching up.

- Price undercutting by other established firms with more financial muscle.

- Availability of cheaper substitutes in the market.

- General economic downturn.

- Financial Management

- Non-availability of adequate credit from banks due to policy measures of the central bank/government.

- Inordinate delay in release of adequate funding by banks and other funding agencies.

SELECT REFERENCES

- Morton Glantz. Managing Bank Risk, Chapter 9, pp. 299–330 (Academic Press, 2003) USA.

- RBI, ‘Guidelines for Rehabilitation of Sick Small Scale Industrial Units’, dated 16 January 2002.

ANNEXURE ii

The following paragraphs summarizes the salient features of RBI’s Framework for revitalizing distressed assets in the economy ( dated February 26, 2014) (Source: RBI web site).

- Borrowing accounts showing incipient stress would be categorized by banks as Special Mention Accounts (SMA). The category was introduced in 2002.

- The SMA category would contain three sub categories as follows:

- SMA-0 Principal or interest payment not overdue for more than 30 days but account showing signs of incipient stress. Box 7.4 provides an illustrative list of signs of stress for classifying a borrowing account as SMA-0 ( as given in the Annexure of the RBI circular dated February 26, 2014 quoted above).

- SMA-1 Principal or interest payment overdue between 31-60 days.

- SMA-2 Principal or interest payment overdue between 61-90 days.

- RBI has set up a Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC) would be set up to collect, store and disseminate credit data to lenders. Banks would be reporting credit information, including classification of an account as SMA to CRILC relating to borrowers having aggregate fund based and non-fund based exposure of ₹50 million and above.

- Once a bank reports a borrower classified as SMA-2, a committee called Joint Lenders’ Forum (JLF) would be mandatorily formed if the aggregate exposure of lenders to that borrower exceeds ₹1000 million. JLF can also be formed for exposures less than ₹1000 million or when the borrower is classified under SMA-0 or SMA-1.

- Where multiple banks are involved in extending credit to the borrower classified under SMA, the consortium leader (where the borrowing limits have been given by a formally constituted consortium of lenders) or the lender with the highest aggregate exposure (in the case of a multiple banking arrangement, which is less formal than a consortium), will convene the JLF to facilitate exchange of credit information.

- The JLF would formulate and sign an Agreement (called the JLF agreement) that would set the broad guidelines for the forum’s functioning. Specifically, the JLF would address the manner in which the borrower can rectify the irregularities or weaknesses observed in the conduct of the account. Other relevant stakeholders such as central/state Government or project authorities could also be invited to JLF deliberations.

- The JLF would arrive at a Corrective Action Plan (CAP). The objective would be to find an early and feasible solution to preserve the economic value of the underlying assets of the borrowers and the loans extended.

- The options under CAP would typically include (a) Rectification, or (b) Restructuring, or (c) Recovery.

- If the option of ‘Rectification’ is chosen, the plan would focus on obtaining a specific commitment from the borrower to regularize the account, so that it emerges out of the SMA category and does not worsen to a Non performing Asset (NPA, the concept of which will be discussed in subsequent chapters). The commitment should be supported with identifiable cash flows within the required time period and without involving any loss or sacrifice on the part of the existing lenders. If the existing promoters are not in a position to bring in additional money or take any measures to regularize the account, the possibility of getting some other equity/strategic investors to the company would be explored by the JLF in consultation with the borrower. These measures are intended to turn-around the entity/company without any change in terms and conditions of the loan. The JLF may also consider providing need based additional finance to the borrower, if considered necessary.

- The option of ‘restructuring’ is considered where the borrower’s business is viable and the borrower is not a wilful defaulter, i.e., there is no diversion of funds, fraud or malfeasance, etc. At this stage, commitment from promoters for extending their personal guarantees along with their net worth statement supported by copies of legal titles to assets may be obtained along with a declaration that they would not undertake any transaction that would alienate assets without the permission of the JLF. Any deviation from the commitment by the borrowers affecting the security/recover ability of the loans may be treated as a valid factor for initiating recovery process. For this action to be sustainable, the lenders in the JLF would sign an Inter Creditor Agreement (ICA) and also require the borrower to sign the Debtor Creditor Agreement (DCA) which would provide the legal basis for any restructuring process. The formats used by the Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR) mechanism (see the later part of this Annexure) for ICA and DCA could be customized and used. Under the ICA, both secured and unsecured creditors have to agree to the final restructuring package.

- Further, a ‘stand still’ clause could be stipulated in the DCA to enable smooth process of restructuring. A ‘stand still’ agreement is an important element of the DCA. The agreement is binding for the period from the date of DCA to the date of approval of restructuring ‘package. Under this clause, both the debtor and creditor(s) shall agree to a legally binding ‘stand-still’ whereby both the parties commit themselves not to take recourse to any other legal action during the period. This would be necessary to undertake the debt restructuring exercise without any outside intervention, judicial or otherwise. However, the stand-still clause will be applicable only to any civil action either by the borrower or any lender against the other party and will not cover any criminal action. Further, during the stand-still period, outstanding foreign exchange forward contracts, derivative products, etc., can be crystallized, provided the borrower agrees to such crystallization. The borrower will additionally undertake that during the stand-still period the documents will stand extended for the purpose of limitation and also that the borrower will not approach any other authority for any relief and the directors of the borrowing company will not resign from the Board of Directors during the standstill period. However, even when the ‘stand-still’ clause is in operation the borrower can make interim payments to the lenders.

- If the options of rectification or restructuring are not found feasible, ‘Recovery’ is the final option. The JLF may decide the best recovery process to be followed, among the various legal and other recovery options available, with a view to optimizing the efforts and results.

- The decisions agreed upon by a minimum of 75% of creditors by value and 60%of creditors by number in the JLF would be considered as the basis for proceeding with the restructuring of the account, and will be binding on all lenders under the terms of the ICA. However, if the JLF decides to proceed with recovery, the minimum criteria for binding decision, if any, under any relevant laws/Acts would be applicable.

- The JLF is required to arrive at an agreement on the option to be adopted for CAP within 30 days from (i) the date of an account being reported as SMA-2 by one or more lender, or (ii) receipt of request from the borrower to form a JLF, with substantiated grounds, if it senses imminent stress. The JLF should sign off the detailed final CAP within the next 30 days from the date of arriving at such an agreement.

- If the JLF has decided on ‘Rectification’ or ‘Restructuring’ as the course of action, but the borrower fails to perform according to the terms agreed upon, the JLF should initiate ‘Recovery’.

- If the JLF decides to restructure an account independent of the CDR mechanism described below, a Techno Economic Viability (TEV) study should be conducted. If the borrower’s business is found viable, the restructuring package should be finalized within 30 days from the date of the final CAP. The TEV and the package should be evaluated by an Independent Evaluation Committee (IEC), comprising of eligible experts. The experts will evaluate the viability and the fairness of the package within 30 days. After the independent evaluation, the package will have to be approved within 15 days for implementation.

- The time limit for finalizing a suitable restructuring package for accounts with aggregate exposure of less than ₹5000 million would be 15 days.

- All time limits specified by RBI are the maximum time that can be taken for finalization of the workout package.

- Wilful defaulters will normally not be eligible for restructuring. However, the JLF may review the reasons for classification of the borrower as a wilful defaulter and satisfy itself that the borrower is in a position to rectify the wilful default. The decision to restructure such cases should however also have the approvals of the board/s of individual bank/s within the JLF who have classified the borrower as wilful defaulter.

- The viability of the account should be determined by the JLF based on acceptable viability benchmarks determined by them. Illustratively, the parameters may include the Debt Equity Ratio, Debt Service Coverage Ratio, Liquidity/Current Ratio and the amount of provision required due to the erosion of the value of the restructured advance, etc. Further, the JLF may consider the benchmarks for the viability parameters adopted by the CDR mechanism.

- Both under JLF and CDR mechanism, the restructuring package should also stipulate the time line during which certain viability milestones (e.g., improvement in certain financial ratios after a period of time, say, 6 months or 1 year and so on) would be achieved. The JLF must periodically review the account for achievement/non-achievement of milestones and should consider initiating suitable measures including appropriate recovery measures.

- The general principle of restructuring should be that the shareholders bear the first loss rather than the debt holders. With this principle in view and also to ensure more participation by promoters, JLF/CDR may consider the following options when a loan is restructured: (a) Possibility of transferring equity of the company by promoters to the lenders to compensate for their sacrifices; (b) Promoters infusing more equity into their companies; (c) Transfer of the promoters’ holdings to a security trustee or an escrow arrangement till turnaround of company. This will enable a change in management control, should lenders favour it.

- For restructuring exposures to listed companies, lenders may be compensated up front for their loss/sacrifice (diminution in fair value of account in net present value terms) by way of issuance of equities of the company up front, subject to the regulations and statutory requirements. In such cases, the restructuring agreement shall not incorporate any ‘right of recompense’ (recovery of ‘sacrifice’ by the lender) clause. However, if the lenders’ sacrifice is not fully compensated by way of issuance of equities, the right of recompense clause may be incorporated to the extent of shortfall. For unlisted companies, the JLF will have option of either getting equities issued or incorporate suitable ‘right to recompense’ clause.

- Banks that fail to report SMA status of the accounts to CRILC or conceal the actual status of the accounts will be subjected to accelerated provisioning (over and above the current provision requirements, as seen in subsequent chapters) for these accounts and/or other supervisory actions by RBI.

- Higher provisions will also have to made for wilful defaulters and ‘non cooperative borrowers’. (A non-cooperative borrower is broadly one who does not provide necessary information required by a lender to assess its financial health even after 2 reminders; or denies access to securities etc. as per terms of sanction or does not comply with other terms of loan agreements within stipulated period; or is hostile/indifferent/in denial mode to negotiate with the bank on repayment issues; or plays for time by giving false impression that some solution is on horizon; or resorts to vexatious tactics such as litigation to thwart timely resolution of the interest of the lender/s. The borrowers will be given 30 days’ notice to clarify their stand before their names are reported as non-cooperative borrowers to CRILC. The definitions and penalties can be found in the RBI instructions.

BOX 7.4 ILLUSTRATIVE LIST OF SIGNS OF STRESS FOR CATEGORIZING AN ACCOUNT AS SMA-0

- Delay of 90 days or more in (a) submission of stock statement / other stipulated operating control statements or (b) credit monitoring or financial statements or (c)non-renewal of facilities based on audited financials.

- Actual sales/operating profits falling short of projections accepted for loan sanction by 40% or more; or a single event of non-cooperation/prevention from conduct of stock audits by banks; or reduction of Drawing Power (DP) by 20% or more after a stock audit; or evidence of diversion of funds for unapproved purpose; or drop in internal risk rating by 2 or more notches in a single review.

- Return of 3 or more cheques (or electronic debit instructions) issued by borrower in 30 days on grounds of non-availability of balance/DP in the account or return of 3 or more bills / cheques discounted or sent under collection by the borrower.

- Development of Deferred Payment Guarantee (DPG) installments or Letters of Credit (LCs) or invocation of Bank Guarantees (BGs) and its non-payment within 30 days.

- Third request for extension of time either for creation or perfection of securities as against time specified in original sanction terms or for compliance with any other terms and conditions of sanction.

- Increase in frequency of overdrafts in current accounts.

- The borrower reporting stress in the business and financials.

- Promoter(s) pledging/selling their shares in the borrower company due to financial stress.

ILLUSTRATION 1

The outstanding advance in the cash credit account of a borrower firm on the date of implementation of the rehabilitation package is ₹60 lacs. The Drawing Power [DP] evidenced by the stock statements, as well as the actual stocks available to cover the advance is ₹20 lacs. The firm started incurring cash losses continuously since 2004. The total interest charged in the account since April 2004 upto the implementation of the relief package is ₹32 lacs.

Step 1: Compare the outstanding advance on the date of implementation of the relief package with the DP on that date. The difference is the irregularity in the cash credit account. Thus,

| A. Outstanding advance on date of rehabilitation | ₹60 Lakhs |

| B. Less: Drawing Power available | ₹20 Lakhs |

| C. Total irregularity on date of implementation [A – B] | ₹40 Lakhs |

Step 2: Compute the interest charged to the cash credit account from the year the firm started showing continuous cash losses, up to the date of the relief package. If this interest exceeds the total irregularity in Step 1, the entire irregularity in the account is to be treated as ‘interest irregularity’ and converted into a funded interest term loan [FITL]. If less, the amount by which the total irregularity exceeds the interest irregularity would be treated as unsecured principal, and converted into a Working Capital Term Loan [WCTL].

| D. Interest charged from the year of cash losses | ₹32 Lakhs |

| E. Difference to be treated as ‘principal irregularity’ [C – D] | ₹8 Lakhs |

| F. The interest irregularity portion to be converted into FITL | ₹32 Lakhs |

| G. The principal irregularity portion to be converted into WCTL | ₹8 Lakhs |

Relief and Concessions from Other Agencies/Institutions

Apart from banks and other lenders, rehabilitation calls for sacrifices from the state and central governments, as well as the management of beleaguered firm itself. An indicative list of such relief measures is provided in Box 7.5.

BOX 7.5 AN ILLUSTRATIVE LIST OF CONCESSIONS AND RELIEF MEASURES THAT CAN BE SOUGHT FOR FROM THE GOVERNMENTS AND THE MANAGEMENT

State Government

- Sales tax loans at low rates of interest;

- Government guarantee for fresh advances from the bank;

- Preferential treatment for power supply, and uninterrupted power supply;

- Rescheduling of payments due for power;

- Duties/levies of the state government waived or provided at a concession;

- Speedier resolution of labour disputes;

- Market support for products to be produced by the firm under rehabilitation;

- Equity contribution, where possible, etc.

Central Government

- Exemption from or reduction of central excise;

- For firms operating in industries catering to public interest, budgetary support through equity or interest free loans

- Adequate market support and price preferences, etc.

Sacrifice from the management

- Waiver or reduction of remuneration;

- Foregoing interest on loans made to the firm;

- Agreeing to reconstitution of Board, if necessary;

- Agreeing for additional collateral, etc.

Sacrifice from Labour

- Agreeing to retrenchment of surplus workers;

- Phasing out retrenchment compensation;

- Agreeing not to make fresh demands till the firm is rehabilitated, etc.

Rights of The Rehabilitating Bank

There are two important rights of the bank rehabilitating a sick firm – the right of ‘review’ and the right of ‘recompense’.

The Right of Review enables the bank to re-assess the assumptions under which the rehabilitation has been embarked upon, and revise conditions of sanction if the actual cash flows of the firm are different from the expected cash flows. For example, the bank can revise the interest rates upward [since they have been lowered to aid the rehabilitation process] if the cash flows from the firm justify the increase, or the base rate increases.

The Right of Recompense entitles the bank to recoup the interest and other monetary ‘sacrifices’—such as reduction in interest rate, funding of interest at reduced rates, conversion of principal/interest into non-convertible debt instruments at lower interest rates, waiver of principal/interest dues, conversion into WCTL, and additional finance—made by the bank, once the firm is rehabilitated, and begins generating adequate positive cash flows.

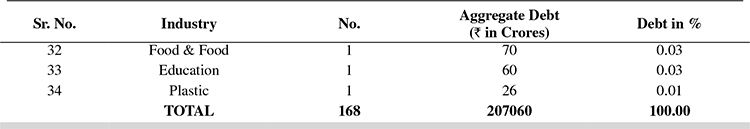

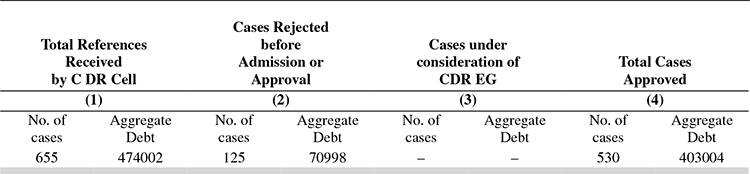

Corporate Debt Restructuring [CDR]18—Salient Features

The CDR Scheme, originally proposed in 2001, was revised for implementation in 2002 based on the recommendations made by the Working Group under the Chairmanship of Shri Vepa Kamesam, Deputy Governor, RBI.

Objectives of the Scheme The objectives of the scheme are:

- Ensuring timely and transparent mechanism for restructuring debts of those corporate entities facing problems, for the benefit of all concerned.

- Preserving viable corporate entities affected by internal and external factors.

- Minimizing losses to creditors and other stakeholders through an orderly and coordinated restructuring programme.

Features The features of the scheme are as follows:

- The scheme operates as a voluntary, non-statutory system.

- It covers all corporate borrowing accounts, whether under multiple banking, syndication or consortium arrangements. However, it will not apply to accounts involving only one FI/bank.

- It is based on the principle of ‘super majority’.

- It is applicable to accounts where the minimum outstanding credit exposure is over ₹10 crores.19

- Cases pending under the BIFR and the Debt Recovery Tribunal are also considered for CD, if such accounts are very large and have been recommended by the CDR Core Group.

- Cases of willful default, frauds and malfeasance are excluded from the CDR scheme.

- Two categories of debt restructuring are provided. Accounts classified as ‘standard’ and ‘sub-standard’ in the books of the lenders, will be restructured under the first category (Category 1). Accounts that are classified as ‘doubtful’ in the books of the lenders would be restructured under the second category (Category 2).

- The accounts where recovery suits have been filed by the lenders against the company, may be eligible for consideration under the CDR system provided, the initiative to resolve the case under the CDR system is taken by at least 75 per cent of the lenders (by value). In addition, the supporting creditors should constitute at least 60 per cent of the number of creditors.20

- OTS would be allowed under the revised guidelines (2005) to make the exit option more flexible.

- Details of CDR during the year should be disclosed in the banks’ financial statements under ‘Notes on Accounts’.

- The accounting treatment of accounts restructured under CDR system, including accounts classified as ‘doubtful’ under Category 2 CDR, would be governed by the prudential norms indicated in RBI’s Master Circular dated July 2, 2012.

The Methodology The methodology is similar to the rehabilitation schemes operated for the SME sector.

- Extending the repayment period of loans.

- Converting the unserviced interest portion into term loans.

- Reducing the rate of interest on outstanding advances.

The CDR Structure The mechanism operates with a three-tier structure, consisting of the following:

- The CDR standing forum: The CDR standing forum would be the representative general body of all FIs and banks participating in the CDR system. It is suggested by the RBI that all FIs and banks should participate in the system in their own interest. The CDR standing forum will be a self-empowered body, which will lay down policies and guidelines and monitor the progress of CDR. The forum will also provide an official platform for both creditors and borrowers (by consultation) to amicably and collectively evolve policies and guidelines for working out debt-restructuring plans in the interests of all stakeholders. A CDR core group will be carved out of the CDR standing forum to assist the forum in convening the meetings and taking decisions relating to policy, on behalf of the forum. The CDR core group would lay down the policies and guidelines to be followed by the CDR empowered group and CDR cell for debt restructuring. These guidelines shall also suitably address the operational difficulties experienced in the functioning of the CDR empowered group. The CDR core group shall also prescribe the timelines for processing of cases referred to the CDR system and decide on the modalities for enforcement of the time frame. The CDR core group shall also lay down guidelines to ensure that over-optimistic projections are not assumed while preparing/approving restructuring proposals.

- The CDR empowered group: This group is the decision-making body for individual cases of restructuring. If the group decides, after studying the preliminary feasibility report, that the restructuring is feasible and the borrower firm is potentially viable, the detailed restructuring package will be worked out by the CDR cell along with the lead lending institution. The time frame allowed for the decision to restructure is 90 days, which, at a maximum, can be 180 days. While approving the restructuring package, the group will also indicate acceptable viability benchmarks such as, ROCE (return on capital employed), DSCR (debt service coverage ratio), the gap between the IRR (internal rate of return) and the COC, and the extent of ‘sacrifice’. If restructuring is not found viable at this stage, the creditors would be free to initiate recovery proceedings.

- The CDR cell: The CDR standing forum and the CDR empowered group will be assisted by a CDR cell in all their functions. The cell will carry out the initial appraisal of the rehabilitation proposals received from borrowers/lenders, and make its recommendations to the CDR empowered group, within 1 month. If restructuring is found feasible, the CDR cell will prepare a detailed rehabilitation plan with the help of lenders and, if necessary, outside experts. If restructuring is not considered feasible, the lenders may start action for recovery of their dues.

The Legal Issues The legal issues are as follows:

- The debtor–creditor agreement (DCA) and the inter-creditor agreement (ICA) provide the legal basis to the CDR mechanism.

- All participants in the CDR mechanism through their membership of the standing forum shall have to enter into a legally binding agreement, with necessary enforcement and penal clauses, to operate the system through laid-down policies and guidelines.

- The ICA signed by the creditors would be a legally binding agreement, with enforcement and penal clauses. The creditors commit themselves under the agreement to abide by the requirements and process of CDR. Further, if 75 per cent of creditors by value and 60 per cent of creditors by number agree to a restructuring package, the decision would be binding on all creditors to an existing debt. The agreement will be initially valid for a period of 3 years and subject to renewal for further periods of 3 years, thereafter. It is to be noted that foreign lenders are not a part of the CDR system.

- An important element of the DCA is the ‘stand-still’ agreement binding on both parties for 90 days or 180 days. Under this clause, both parties commit to a stand-still—implying that the parties would not resort to any other legal action during this period.

- However, the standstill clause will not be applicable to criminal action against any of the counter parties. Further, during the standstill period, issues like outstanding foreign exchange forward contracts, and derivative products can be crystallized, provided the borrower is agreeable to such crystallization. The borrower will additionally undertake that during the stand-still period the documents will stand extended for the purpose of limitation and also that he will not approach any other authority for any relief and the directors of the borrowing company will not resign from the Board.

- All CDR approved packages must incorporate creditors’ right to accelerate repayment and borrowers’ right to pre-pay. The right of recompense should be based on certain performance criteria to be decided by the Standing Forum.

Debt restructuring for Small, Medium Enterprises (SME)

An exercise similar to CDR, though much simpler, can be done for restructuring advances to SME borrowers. This schemed is applicable to borrowers with funded and non funded outstanding advances of upto Rs 10 crore under multiple banking arrangements. The operational details of the restructuring can be decided by banks internally. The scheme should be formulated with approval from the Bank’s Board, and within the overall framework of the RBI.

Schemes can be tailored to the different sectors of borrowers. The bank having the largest exposure to the borrower will work out the details of the scheme, supported by the second largest lender. The restructuring package will have to be formulated and implemented within 90 days in terms of the current guidelines.

Strategic Debt Restructuring Scheme (SDR)

It has been observed that in many cases of restructuring of accounts, borrower companies are not able to come out of stress due to operational/ managerial inefficiencies despite substantial sacrifices made by the lending banks. In such cases, change of ownership will be a preferred option.