CHAPTER SIX

Banks in India—Credit Delivery and Legal Aspects of Lending

CHAPTER STRUCTURE

Section I Modes of Credit Delivery

Section II Legal Aspects of Lending

Annexures I, II, III, IV (Case Study)

KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM THE CHAPTER

- Know the types of borrowers in India.

- Learn about some types of credit that banks in India extend to borrowers.

- Learn about the forms in which the credit is given.

- Know the precautions banks should take while lending.

- Know how banks in India fix interest rates for individual borrowers.

- Understand how the law helps the bank in enforcing securities.

SECTION I

MODES OF CREDIT DELIVERY

We have seen the basic principles and processes of the lending function in the previous chapter. The con cepts discussed in the chapter have universal applicability. We will learn in this chapter how these concepts are applied by Indian banks.

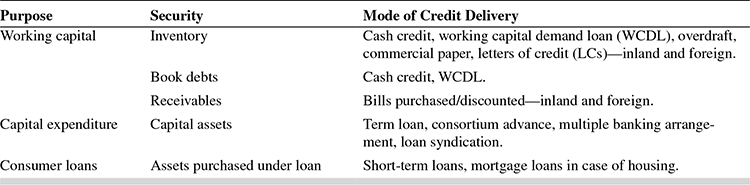

Typical credit delivery modes used by Indian banks are summarized in Table 6.1.

The features of each of these credit delivery modes are designed to help the borrower carry on operations without interruption, simultaneously facilitating recovery of the debt for the lending bank. The terms and conditions, the rights and privileges of the bank and borrower differ in each case, as described below.

Annexure I provides an overview of the methods of lending prevalently used by Indian banks for various purpose-oriented loans.

Cash Credit

The cash credit system used to be the dominant mode of lending and the most preferred by borrowers. However, this mode of credit delivery is gradually being replaced by the short-term loan for reasons that will be discussed below.

Under the cash credit system, the bank specifies a credit limit for the borrower. The credit limit is backed by prime securities in the nature of inventories or book debts or receivables, and collaterals and guarantees, if the bank so insists.

The cash credit account is almost a mirror image of the ‘current deposit account’, and is operated in quite the same manner, except that the balances in the cash credit account are predominantly debit balances. The customer withdraws funds from the account for operating expenses, and deposits the cash inflows, primarily by way of sales. The bank generally stipulates that the account should be ‘brought to credit’ periodically, the periodicity of such credit depending on the cash-to-cash cycle. Hence, the sum of the credits in the account should practically reflect the ‘sales’ achievement of the firm for the period. This can be verified by the bank by periodically calling for the borrower’s sales revenue data. The bank can also question the borrower when there is a substantial difference between the actual sales achievement of the borrower and the sum of ‘credits’ into the cash credit account. Such a discrepancy should be taken seriously by the lending bank since it could imply that the borrower is diverting bank funds either to long-term uses or for purposes other than those for which such funds were intended. Such practices could ultimately jeopardize the bank’s chances of recovering the amount lent.

The bank also levies a ‘commitment charge’ on the unutilized portion of the cash credit limit. The magnitude of the commitment charge reflects the bank’s opportunity cost of earmarking a portion of its liabilities for the loan assets created for the borrower.1

While the cash credit system provides great flexibility and operational convenience to borrowers, it leads to higher transaction costs for the bank, in the form of monitoring and opportunity costs. In the present competitive and profit-focused environment, the banks may find the system cumbersome and costly to operate.

Hence, to usher in discipline in the funds utilization of large borrowers and in still efficient funds management in banks, the loan system for delivery of bank credit was introduced in the mid 1990s. Though the new system is mandatory for borrowers enjoying working capital limits of over ₹10 crore from the banking system, the central bank encourages all borrowers to adopt the system. The system stipulates that the assessed working capital requirements of the borrower will be delivered as two components—a loan component, called the WCDL, constituting not less than 80 per cent of the assessed credit limit, with the ubiquitous cash credit component forming the remaining 20 per cent.

Loan System for Delivery of Bank Credit—The Working Capital Demand Loan

RBI Guidelines—Loan component and cash credit component2

Banks may change the composition of working capital finance by increasing the cash credit component beyond 20 per cent or increasing the loan component beyond 80 per cent, where warranted.

- Each component should be priced3 appropriately, taking into account the impact of such decisions on banks’ cash and liquidity management.

- A higher loan component can be granted by the bank within the overall assessed credit limits. Hence, a higher loan component would entail a corresponding reduction in the cash credit component of the total credit limit.

- Banks may persuade borrowers with working capital (fund-based) credit limit of less than ₹10 crore to adopt the loan system by offering an incentive in the form of lower rate of interest on the ‘loan component’ as compared to the ‘cash credit component’. The actual percentage of ‘loan component’ in these cases may be mutually negotiated.

- In cyclical, seasonal or inherently volatile industries, strict application of the loan system may affect the borrowers. Hence, banks may exempt such borrowers from the loan system of credit delivery, with their Board of Directors’ approval.

The repayment of these loans will be periodical, within the assessed period for which the credit limit has been granted. For example, the bank may want the WCDL repaid every quarter, with a replenishment of the limit for the next quarter, within the overall credit limit. The periodicity of the WCDL being ‘brought to credit’, like the cash credit, will be closely linked to the working capital cycle of the borrower.

Therefore, the WCDL is a more disciplined version of the cash credit system, with more advantages for the lending bank.

Overdrafts

Overdrafts are like cash credits because they are permitted as withdrawals over and above the borrower’s credit balance in his current account. But overdrafts are unlike cash credits in that they are not purpose-oriented. The bank may grant an overdraft to satisfy urgent credit requirements of a borrower against a collateral security or personal guarantee.

The contract of an overdraft can be express or implied. In the case of an express contract for an overdraft, the customer approaches the bank with a request, which is appraised by the bank, the primary requisite being the track record of the borrower and his integrity. In some cases, when the overdraft is requested as a continuing facility, suitable collateral security is taken. The bank can also stipulate the number of times the account should be ‘brought to credit’ or minimum repayments into the account, during the period for which the overdraft is granted.

Since the credit is not purpose-oriented, and the securities may or may not be tangible, the risks are greater. Therefore, the interest rate on the overdraft account is normally fixed higher than that for other loan accounts.

An implied overdraft is created when the customer overdraws on the balance in his account, and the bank does not dishonour the payment. Can the bank charge interest on such overdrawn balances? Is the customer liable to repay, since there is no express contract between the bank and the customer? The Bombay High Court has decreed that an implied contract of overdraft arises when the customer overdraws on his account, and he is liable to compensate for the bank’s outlay of funds with interest, as well as repay the amount overdrawn.4

Can an implied contract of overdraft be terminated by the bank without giving the customer reasonable notice? The Gujarat High Court has ruled that the bank cannot unilaterally terminate the contract, even if it is called a ‘temporary overdraft’.5

Bills Finance

This is one of the very important modes of credit delivery. Typically ‘bill financing’ occurs when bills of exchange (BOE) (as defined in Annexure I) drawn by the borrower or by counter parties on the borrower, are discounted by the bank. On the basis of payment obligations on the part of the bank, the methods of bills finance can be classified into the following:

- Purchase of bills

- Discounting of bills

- Drawee bill acceptance

- Bills co-acceptance

In all these cases, the banker takes on an obligation, with the only difference that the first two are fund-based facilities and the remaining two are non-fund based.

The fund-based facilities—purchase of bills and discounting of bills arising out of sale of goods or services— score over cash credit and other types of working capital finance on the following counts:

- Bills ensure a definite payment date.

- The transactions underlying raising the bill can be easily identified and tracked.

- Bills are backed by legal provisions, leading to better control.

- Bills are negotiable instruments, i.e., any person to whom the bill is transferred in accordance with the provisions of the Negotiable Instruments Act, would be entitled to receive the amount of the bill.

Bills purchased and discounted by banks fall under one of the following categories:

- Clean bills

- Documentary bills

- Supply bills

Clean Bills This is a bill of exchange not supported by any documents of title to goods,6 since the seller has already delivered the goods and the documents to the buyer. Clean bills are also drawn to effect discharge of a debt or claim. Clean bills are treated like unsecured advances by banks, since their realization depends on the honesty and creditworthiness of the counter parties.

Documentary Bills A bill of exchange accompanied by documents of title to goods is a documentary bill. The goods have been despatched by the seller but the transfer of documents of title to goods has not yet taken place. Examples of documents of title to goods are lorry receipts, railway receipts, airway bills and bills of lading. Documentary bills are considered safer than other types of bills since they are backed by the security of documents of title to the goods, and they are either made in favour of the bank or endorsed in favour of the bank thus enabling the bank to liquidate the goods and realize its debt, in case the bill is not paid.

There are two types of documentary bills—documentary demand bills or documents against payment (D/P) and documentary usance bills or documents against acceptance (D/A).

D/P bills are similar to cash sales in that the buyer has to pay the bank before collecting the documents and taking delivery of the goods. In this type of transaction, the seller draws the bill on the buyer and sends the bill to his bank along with the documents of title to goods, instructing the bank to hand over the bill and documents only when the buyer pays for the goods.

D/A bills are similar to credit sales with a specified credit period or usance period. The usance bill is supported by documents of goods and bears the instruction to the bank that the documents can be delivered to the buyer if he ‘accepts’ the bill in writing. The bank finances the seller against the ‘accepted’ bill and holds the accepted bill till it is paid on the specified date. On the due date, the bill is presented for payment and the credit is adjusted.

It is easy to see why banks consider D/P bills safer than D/A bills. A usance bill turns into a ‘clean’ bill, since once the buyer accepts the bill, the documents are delivered and the buyer takes possession of the goods. Thereafter, the bank will have to depend solely on the ‘acceptance’ of the buyer, till the bill is paid. Hence banks should be cautious while purchasing or discounting bills on D/A basis.

Supply Bills These bills do not fall in the ambit of the Negotiable Instruments Act. They are in the nature of ‘debts’ and can be assigned in favour of the bank.

Supply bills are raised when the buyer is the government or a large corporation. In this case, the seller or supplier delivers the goods against a specified ‘work order’, and produces documents evidencing despatch of goods, such as a railway receipt or a bill of lading. These goods have to be inspected by the buyer, and once he is satisfied, an invoice is raised on the buyer. The supplier submits the invoice along with the buyer’s certification of acceptance of the goods to the bank for financing, till the invoice is processed by the buyer and payment is received.

Banks take care to lend against supply bills only to borrowers who have a proven track record of supplies to the government or large corporations. The charge is only an ‘assignment’ (see the next section for definition of assignment) and, therefore, advances against supply bills are ‘clean’ advances—the bank may not realize the full amount of the bill due to a counterclaim or set off by the government.

Precautions to be Taken While Purchasing/Discounting Bills

- The facility should be granted only to creditworthy borrowers

- The bank being able to realize the amounts advanced against bills depends on the drawee’s ability to pay. Hence, banks should obtain credit reports on the buyers before agreeing to purchase or discount bills drawn on them. The bank can choose not to advance against bills drawn on certain buyers or categories of buyers. The bank can also fix maximum amounts up to which it will purchase/discount bills drawn on specific buyers (called drawee-wise limits).

- The genuineness of the transactions should be verified before advancing against bills. A gist of the RBI guidelines issued in this respect is provided in Box 6.1.

BOX 6.1 RBI GUIDELINES ON DISCOUNTING/REDISCOUNTING7 OF BILLS BY BANKS

The salient features of RBI’s guidelines to banks while purchasing/discounting/negotiating/rediscounting of genuine commercial/trade bills are summarized below.

- Sanction of credit limits for working capital and bills to borrowers should be done after proper appraisal of their credit needs and in accordance with the loan policy approved by their Board of Directors.

- RBI recommends that banks clearly lay down a bills discounting policy approved by their Board of Directors, consistent with their policy of sanctioning of working capital limits. In this case, the procedure for Board approval should include banks’ core operating process from the time the bills are tendered till these are realized. Banks should also review their core operating processes and simplify the procedure in respect of bills financing, where feasible. RBI also urges banks to take advantage of improved computer/communication network like structured financial messaging system, wherever available, and adopt the system of ‘value dating’ of their clients’ accounts to mimimize problems, such as late realization of bills.

- Banks should open LCs and purchase/discount/negotiate bills under LCs only in respect of genuine commercial and trade transactions of their borrowers who have been sanctioned regular bank credit facilities. This effectively implies that banks should not extend fund-based (including bills financing) or non-fund based facilities like opening of LCs, providing guarantees and acceptances to non-constituent borrower or/and non-constituent member of a consortium/ multiple banking arrangement.

- Bank Guarantee (BG) or Letter of Credit (LC) can be issued by scheduled commercial banks to clients of co-operative banks against counter guarantee of the co-operative bank, and subject to rules in force. It is also important that the cooperative bank requesting for these facilities demonstrates existence of sound credit appraisal and monitoring systems and a robust KYC process, which has been employed to assess the client.

- However, irrespective of who has issued the LC, the bills arising out of the LC transaction would have to be discounted only by the bank with whom the exporter has credit facilities. This is to ensure that the bank sanctioning credit facilities to the exporter is not deprived of income and business growth.

- While purchasing/discounting/negotiating bills under LCs or otherwise, banks should establish genuineness of underlying transactions/documents.

- The practice of drawing BOE with ‘without recourse’ clause, and issuing LCs bearing the legend ‘without recourse’ should be discouraged because such notations deprive the negotiating bank of the right of recourse it has against the drawer under the Negotiable Instruments Act. Banks should not, therefore, open LCs and purchase/discount/negotiate bills bearing the ‘without recourse’ clause.

- Accommodation bills—that is, bills not supported by genuine trade transactions—should not be purchased/discounted/negotiated by banks.

- Banks should be careful while discounting bills drawn by front finance companies set up by large industrial groups on other group companies.

- Bills rediscounts should be restricted to usance bills held by other banks. Banks should not rediscount bills earlier discounted by non-bank financial companies except in respect of bills arising from sale of light commercial vehicles and two/three wheelers.

- Banks can discount bills of services sector, after ensuring that actual services are rendered and accommodation bills are not discounted. Services sector bills are not eligible for rediscounting. Further, providing finance against discounting of services sector bills should be treated as ‘unsecured advance’.

- RBI notes the need to promote ‘payment discipline’ in bills financing. One measure suggested is that all corporate and other constituent borrowers having turnover above threshold level as fixed by the bank’s Board of Directors should be mandated to disclose ‘aging schedule’ of their overdue payables in their periodical returns submitted to banks.

- Bills discounted/rediscounted cannot be used as collateral for repo transactions by banks.

Advances Against Bills Sent on Collection

The bank advances against bills that are in the process of collection, after retaining a suitable margin. In all the above cases—purchase, discount and advances against collection of bills—the bank becomes ‘holder in due course’8 for the bills.

Drawee Bills In the earlier cases, the drawer of the bill, who is the seller, is financed by the bank. When the bank finances the buyer, the drawee, the buyer’s bank itself discounts the bills and sends the amount to the seller. This has the effect of financing the purchases of the buyer. The buyer’s bank grants an ‘acceptance credit’ to the buyer and accepts bills up to this limit. In short, drawee bills finance purchase of inputs and raw materials, while drawer bills (in the cases discussed above) finance receivables.

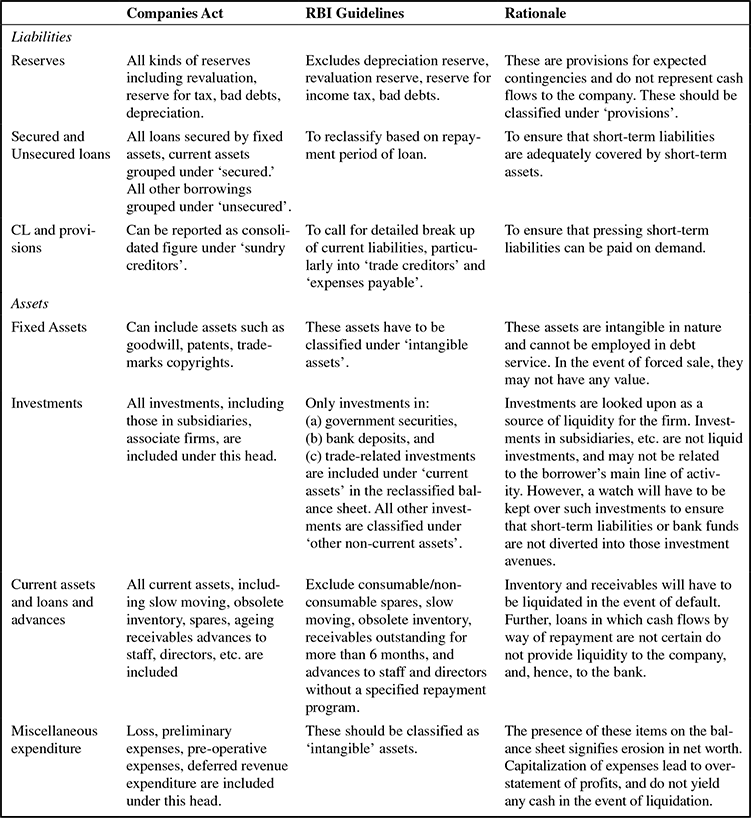

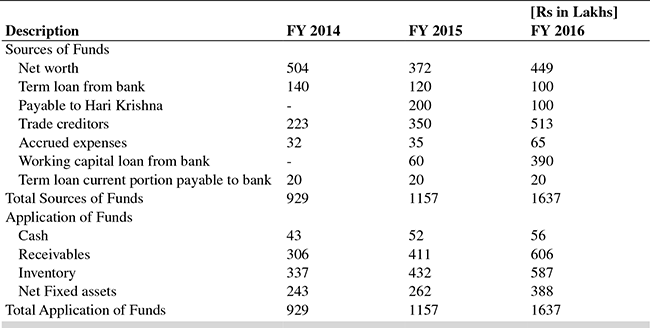

Annexure II outlines the broad guidelines to banks in India for reclassifying financial statement items for the purpose of credit appraisal.

Pricing of Loans

Banks in India are given the freedom to price loans with the objective of sustaining their profitability. However, for certain classes of borrowers, the interest rates will have to conform to the periodic RBI directives, the latest directive having been issued on March 29, 2016.

The previous chapter has described a generic model of loan pricing that is comparable to pricing any product taking into account variable costs, fixed costs, and profit margin, as well as a premium that is unique to the financial instruments, that of risk.

The internal benchmark interest rates are unique to each bank in India and are calculated following a similar procedure. Please note that the external financial benchmarks described in the previous chapter are published by external benchmark administrators for the industry as a whole, while the internal benchmarks are more bank specific.

In 2010, the concept of “Base rate” was introduced as the internal benchmark rate. It was calculated as follows:9

Base rate = Cost of deposits/ funds + Negative carry on CRR/ SLR + Unallocated overhead costs+ Average return on net worth

Thus, the base rate served as the minimum lending rate to borrowers. To reflect the borrower or instrument specific risk, a risk premium would be added to the base rate, that would be quoted as the interest rate to the borrower.

The base rate used predominantly the “average cost of funds”. We have seen in the previous chapter that using the average costs of funds as the variable cost to determine the loan price could understate the interest rate. This means that the bank would make lower profit if the average cost of funds did not reflect the real cost of funds used to create the loan.

The above concern has been addressed in the move towards “Marginal cost of funds based lending rate” (MCLR).

All rupee loans sanctioned and credit limits renewed from. April 1, 2016 are to be priced with reference to the MCLR, that will now serve as the internal benchmark for banks.10

Calculating the MCLR

Each component is explained below

- Marginal cost of funds

This comprises of the marginal cost of deposits and borrowings, and a return on net worth. The process of arriving at the marginal cost of deposits and borrowings is set out in the Annexure to the RBI Directions quoted above, as well as RBI guidelines on Asset Liability Management (ALM) – amendments, dated October 24, 2007. The marginal cost is calculated as the product of the rates offered on each head of deposits/ borrowings on the date of review, (or the actual rates at which the funds were raised,) and the balance outstanding in the deposit / borrowing head taken as a percentage of total funds (other than equity).

Since return on net worth is also part of cost of funds for a bank, its marginal cost of funds will be calculated as follows:

Marginal cost of funds = (92% * marginal cost of deposits and borrowings) + (8% * Return on net worth)Return on net worth is reckoned as the cost of equity. Under Basel III requirements (Please refer to the relevant chapter), the common equity tier 1 (CET1) capital is required to be 8% of Risk Weighted Assets. Hence, the weightage given for this component is 8%. The return on net worth or cost of equity is the minimum desired rate of return on equity over the risk free rate. Banks can compute cost of equity using any pricing model such as the Capital Asset Pricing model (CAPM) to arrive at the cost of equity capital. (For more details on various pricing models for calculating cost of capital, please refer to a standard text book on Corporate Finance).

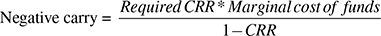

- Negative carry on CRR

“Negative carry” denotes a loss of income or profit that could arise when funds are sourced at a higher cost than the return on investment of these funds. Investment in CRR does not earn for a bank, since no interest is paid by RBI on CRR balances. However, the bank has to pay interest to depositors and others for sourcing the funds from which the CRR is maintained.

The marginal cost of funds arrived at in (a) above is used in calculating the negative carry.

- Operating Costs

All operating costs associated with the loan (see the example on Customer Profitability in the previous chapter) will be included under this head. However explicit service charges that are charged separately, such as upfront processing fees, will not be added in this component.

- Tenor premium

The tenor premium is not borrower or loan class specific. For a given tenor of loan (residual maturity), the tenor premium would be the same. Calculation of the tenor premium is shown in the Annexure to the 2016 instructions of RBI. More clarifications can be found under the head FAQs on the subject on the RBI website.

Since MCLR is a tenor linked benchmark, internal benchmarks will have to be published by banks for various maturities such as overnight MCLR, one month MCLR, three month MCLR, six month MCLR, one year MCLR, and MCLR for longer maturities as well.

In addition to the MCLR as an internal benchmark, banks can determine interest rate on loans to specific borrowers based on market determined external benchmarks (described in the previous chapter).

- Spread

The components of ‘spread’ linked to the loan price would be decided by each Bank’s Board. The policy would have to include principles governing quantum of each component of spread, the range for a borrower category or loan type, and the powers delegated for loan pricing.

Under the MCLR, two components of ‘spread’ are to be adopted –Business Strategy and Credit Risk premium.

The component related to “Business Strategy” would include considerations such as business strategy, market competition, embedded options in the loan (eg- prepayment etc), market liquidity of the loan and similar aspects.

The component related to ‘credit risk premium’ would reflect the default risk based on an appropriate credit risk rating or scoring model, that would also include factors such as customer relationship, expected losses, and collaterals. (More on Credit Risk models can be found in later chapters).

The spread charged to an existing borrower cannot be increased unless there is a deterioration in the credit risk profile of the customer, and the increase should be supported by full fledged risk profile review of the customer.

Reset of interest rates under MCLR

Reset dates for loans are to be specified by individual banks, and can be linked to the date of sanction of credit limits or date of review of MCLR. The MCLR prevailing on the date of disbursement will be applicable till the next reset date. Periodicity of reset will be one year or lower, and is to be specified in the loan contract.

Interest rates on advances made in foreign currency

Bank’s policy on interest rates would be approved by the Board. These interest rates would be determined with reference to an external benchmark (as described in the previous chapter).

Exemptions

The types of loans that would be exempted from the provisions of the MCLR, and not linked to the MCLR, include the following:

- Government schemes not linked to base rate.

- Working Capital Term Loan (WCTL), Funded Interest Term Loan (FITL), and other loans granted as part of rectification / restructuring packages (Please refer to the next Chapter for details).

- Loans granted under various refinance schemes.

- Advances to banks/ depositors against their own deposits.

- Advances to banks’ employees, including retired employees.

- Advances to banks’ directors/ CEOs.

- Loans linked to a market determined external benchmark, that is above the MCLR.

- Fixed rate loans with maturity above three years, provided the interest rate so fixed is above the MCLR.

SECTION II

LEGAL ASPECTS OF LENDING

We have seen in the earlier chapter on ‘Banks’ Financial Statements’ that loans and advances can be classified by security arrangements into ‘secured’, ‘covered by bank/government guarantees’ and ‘unsecured’ loans.

What are Unsecured Loans?

If a loan is not backed by any tangible security, except the personal guarantee of the borrower himself or a third party, the loan is classified as ‘unsecured’. In the event of borrower default, the bank will be ranked an unsecured creditor and gets no seniority in claiming against any property of the borrower. Hence, banks generally do not create unsecured loans unless the borrower is well established, has a track record of integrity and prompt repayments, and the bank has confidence in the borrower’s future solvency, otherwise called ‘creditworthiness’.

A notable exception is those loans covered by guarantees of the government or other banks. Balances under advances within India and granted abroad, covered by guarantees of Indian or foreign governments, or by agencies such as ECGC, are categorized under ‘advances covered by bank/government guarantees’ and are not considered unsecured.

What are Secured Loans?

A major portion of bank loans and advances fall under this category. Though a bank lends only to creditworthy borrowers, tangible securities are sought for the credit extended, over and above the assessed ‘creditworthiness’ of the borrower. This is to safeguard the bank’s interest in the worst case scenario.

Secured loans are backed by tangible assets in the form of ‘floating’ or ‘fixed’ assets. Examples of floating assets are current assets, where the composition of the assets keeps changing over a specified period of time, the amount secured being constant. Examples of fixed assets are plant and machinery or land and buildings, whose composition cannot be altered in the short term without substantial investment. In some categories of advances, documents and commodities also form part of tangible securities.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, the securities can be ‘prime’ or ‘collateral’ in nature.

Securities and Their Features Can the banker accept any asset offered by the borrower as security for the advances made? Some basic safeguards observed while accepting assets as securities would help the bank recover most of its dues in the event of default.

Safeguard 1—Ensure adequate ‘margin’: For a bank, ‘margin’ signifies the difference between the market value of the security and the amount of advance granted against it. For example, if the bank has sanctioned ₹75 lakh as advance against a security worth ₹1 crore, the bank has a margin of ₹25 lakh (100 – 75 = ₹25 lakh). The rationale for adequate margin stems from the following factors:

- The market value of the security may fluctuate in future. If the market value falls, but the amount of advance remains the same, the bank’s security cover may be eroded.

- The interest to be paid on the advances enlarges the dues to the bank over a period of time. Even if the borrower defaults on interest payments, the value of securities held should cover the total dues to the bank.

- The quantum of margin varies with types of securities and the customers who offer these securities. For example, the margin against an essential commodity with stable demand and prices would be different from the margin against a commodity whose prices and demand fluctuate widely. The margin against prime property offered as security would be less than the margin against company shares offered as securities. The margins stipulated for advances made to first class customers of the bank may be lower than for an advance made to a first generation entrepreneur’s start up venture.

Safeguard 2—Easy marketability: In case of default, the security should have wide and ready marketability, to enable the bank sell off the security and realize its dues. For example, gold or jewels held as security are more liquid since they have wider marketability than, say, real estate.

Safeguard 3—Documentation: The bank’s security interest is evidenced by legally valid documents that are executed by the borrower. These documents have to be periodically reviewed, especially in the case of securities for long-term loans or revolving credits, to ensure that the documents are kept enforceable and the legal limitation period for such agreements does not render the agreements invalid.

Some commonly accepted securities and their relative merits are discussed in Annexure III.

What is a ‘Security’?

Though commonly used by bankers, ‘security’ is not defined in any act. The Provincial Insolvency Act defines a ‘secured creditor’ as one who holds a mortgage, lien or charge on the property of a debtor, as security for a debt due from the debtor. In banking parlance, securities accepted by banks fall into the following categories:

- Pledge

- Hypothecation

- Assignment

- Lien

- Mortgage

When the bank accepts different securities in respect of loans granted, the bank is said to have a ‘charge’ over the assets which constitute these securities.

We will now elaborate upon the various types of securities and their features.

Pledge: Section 172 of the Indian Contracts Act, 1872, defines ‘pledge’ as ‘bailment of goods as security for payment of a debt or performance of a promise’. The bank (pledgee) enters into an explicit contract of pledge with the borrower (pledgor), under which the securities are delivered to the bank. Such delivery of possession can be actual or constructive. Thus, a pledge implies (a) bailment11 of goods, and (b) that the objective of bailment is to hold goods as security for the payment of a debt or performance of a promise.

The primary advantage of pledge is that the goods are in the ‘possession’ of the bank thus preventing security dilution by the borrower. However, the bank would find holding goods of various borrowers under pledge a cumbersome exercise, since the bank, as the pledgee, has to take reasonable care of the goods and any loss has to be compensated to the borrower. This entails higher monitoring and inspection costs for the bank.

The disadvantages cited above, along with the risks associated with the nature of the goods under pledge,12 have rendered this type of security unpopular.

Hypothecation: This is one of the most popular methods of creating security interest for banks, and is characteristic of the banking industry. Interestingly, ‘hypothecation’ is not governed by any identifiable Act in law. Simply defined, hypothecation is a legal transaction involving movable assets, amounting to an ‘equitable charge’ on the assets. The difficulties of holding the security in the bank’s custody are removed in hypothecation, as the security interest is created without transferring the possession of assets to the bank. In hypothecation, the security remains in the possession of the borrower, and is charged in favour of the bank through documents executed by the borrower. The documents contain a clause that obligates the borrower to give possession of the goods to the bank on demand. Once possession over the goods is relinquished by the borrower, hypothecation becomes similar to pledge.13

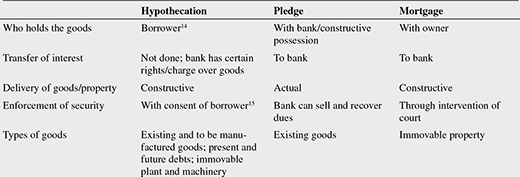

How does hypothecation differ from ‘pledge’ and ‘mortgage’? Box 6.3 explains in brief.

BOX 6.3 HYPOTHECATION DIFFERENTIATED

Though the cumbersome procedures under pledge are eliminated by the process of hypothecation, the latter is more risky for the bank. Since the securities are in the borrower’s possession, the borrower can fail to give possession to the bank on demand, or sell the securities without the bank’s knowledge, or borrow from another bank on the strength of the same securities. In this respect, advances under hypothecation are as risky as unsecured or clean advances.

The bank will therefore have to take the following precautions:

- Credit limits with hypothecation should be sanctioned only after ascertaining the creditworthiness and integrity of the borrower.

- Only fully paid stocks will be hypothecated to the bank.16

- The bank has the unrestricted right of inspection of stocks and the related books of the borrower. Such inspection should be done periodically to ensure that the stocks under hypothecation provide adequate cushion for the advances. In the process, the bank should also eliminate slow moving and obsolete stocks while estimating security coverage.

- Stocks should be fully insured against fire and other risks as specified by the bank.

- The borrower should submit a statement of stocks at the periodicity specified by the bank, based on which the drawing power under the credit facility will be determined.

- The borrower should also declare in the above statement that the borrower has clear title to the stocks and that slow moving or obsolete stocks have been excluded.

- To prevent the borrower hypothecating the same stocks to another lender, the borrower should display in a prominent place in his premises/factory/godown the fact that the stocks are hypothecated to the credit-disbursing bank.

- If the borrower is a limited company incorporated under the Indian Companies Act, the hypothecation should be registered with the Registrar of Companies under Section 125 of the Companies Act, 1956, within 30 days of signing the documents. This aspect will be discussed in detail under the heading ‘charge’.

- To enforce its claim, it is essential for the bank to take possession of the hypothecated property on its own or through the court. If the bank fails to take possession and seeks a simple money decree from the court, then the bank is presumed to have relinquished its right as hypothecatee.17

TEASE THE CONCEPT

If a vehicle hypothecated to a bank under vehicle loan is involved in an accident, and the passengers are injured, will the bank be liable for compensation to the victims?

An interesting point in this connection is the position of the ‘guarantor’ to the loan given by a bank to its borrower, who sells goods hypothecated to the bank without the bank’s knowledge and does not repay the debt owed to the bank.

Under the above circumstances, the question is whether the guarantor is discharged from his liability since the goods were sold without the guarantor’s consent (section 141 of the Contracts Act). Since the rights and obligations of a hypothecator and the hypothecatee are not defined precisely under a specific Act, courts have so far taken different and sometimes, opposing stances regarding the rights and obligations of various parties under hypothecation.18

Assignment: Borrowers ‘assign’ actionable claims to the bank. Section 130 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882, permits an assignment to anyone except a judge, legal practitioner or an officer of the court of justice. Section 3 of the act defines actionable claim as ‘a claim to any debt, other than a debt secured by mortgage of immovable property or by hypothecation or pledge of movable property, or to any beneficial interest in movable property not in the possession, either actual or constructive, of the claimant, which the civil courts recognize as affording ground for relief, whether such debt or beneficial interest be existing, accruing, conditional or contingent’.

What are the actionable claims a borrower can assign to a bank?

- Book debts

- Money due from government departments or semi-government organizations.

- Life insurance policies

Assignment takes two forms—(1) legal assignment; and (2) equitable assignment. A legal assignment, which is in writing by the assignor, constitutes an absolute transfer of the actionable claim. The assignor also informs his debtors of the assignee’s interest, which is followed up by the assignee seeking confirmation from the debtors of the balances assigned. In the case of equitable assignment, the above conditions are absent.

The bank gets absolute right over the funds assigned to it. Once the borrower assigns his claims to the bank, other creditors of the borrower cannot get priority over the bank in the realization of their dues from the assigned debts.

TEASE THE CONCEPT

Bankers’ Lien: This is one of the most important rights of the lending bank. ‘Lien’ is the right of the bank to retain the securities given by the borrower until the debt due is fully repaid.

Lien is of two kinds—general lien and particular lien. Section 171 of the Indian Contracts Act, 1972, confers the right of general lien on the bank, stated as ‘Bankers…may, in the absence of a contract to the contrary, retain as a security for a general balance of account, any goods bailed to them.’ In the case of a particular lien, specific securities are earmarked for a specific debt. Once the debt is satisfied, the lien ceases to have effect. Example of a particular lien is that marked on a fixed deposit against which a loan has been taken. Once the loan is repaid, the fixed deposit becomes unencumbered.

The distinguishing features of the bankers’ right of general lien are the following:

- The general lien can be exercised by the bank only on ‘all the goods and securities entrusted to it in its capacity as ‘banker’ and in the absence of a contract inconsistent with the right of lien’. Circumstances under which the banker cannot exercise the right of general lien are one of the following:

- The goods and securities have been entrusted to the banker as a ‘trustee’ or an ‘agent’ of the customer.

- The goods and securities have been entrusted for a specific purpose.

- A banker’s lien is tantamount to an ‘implied pledge’. It confers upon the bank the right to sell the goods and securities in case the borrower defaults. Since this right resembles a pledge, the lien is called an ‘implied pledge’. The bank can sell the securities to realize its dues after giving proper notice to the borrower.

- The right of lien is conferred by the Indian Contract Act, and therefore, tacitly understood by both banker and borrower. However, as a precaution, banks take a letter of lien from the borrowers acknowledging the right of lien over securities for existing as well as future loans.

- The right of lien extends to securities and goods belonging solely to the borrower and does not include securities owned jointly with others.

- If no contract to the contrary exists, the bank can exercise its lien over the securities remaining even after the loan, for which they were pledged, are repaid by the borrower. The bank can also exercise its general lien in respect of a customer’s obligation as a guarantor, and retain the security offered by him for a loan granted on a personal basis, even after the loan has been fully repaid.

The following are the exceptions to the right of general lien:

- Goods entrusted for safe custody: A customer’s documents, ornaments and other valuables deposited with the bank for safe custody or as trustee, is a contract inconsistent with the right of lien.

- Securities earmarked for a specific purpose: Customers may sometimes entrust the bank with shares or BOE, meant for a specific purpose, say, for sale or for honouring another liability, which contract is inconsistent with the right of lien.

- Sometimes, the banker’s general lien may be replaced by a particular lien due to certain special circumstances. The right of the banker is interpreted by what is written by the banker in respect of the security rather than the printed word.

- The bank has no lien over securities left with the bank by oversight or negligence by the borrower.

- The bank cannot exercise right of lien over securities given to the bank as collateral for a loan, before such loan is actually granted or disbursed.

- The bank’s right of lien extends only to securities and goods and not to money deposited with the bank, or the borrower’s credit balances. In the latter case, the bank can exercise its right of ‘set off’.

What is ‘Right of Set Off’? The bank’s right of set off enables it to adjust the credit balance (or deposit) in one account of a customer with the debit balance (or loan) in another account of the same customer. For example, if a customer has a term deposit of ₹2 lakh, and he owes ₹3 lakh to the bank, the bank can combine both the accounts, set off the deposit amount against the loan amount, and claim the remaining ₹1 lakh from the customer. The right of set off can be exercised under the following conditions:

- The accounts must be in the same name.

- The accounts must also be in the same right. This implies that the deposit funds are held by the customer in the same right or capacity in which he owes funds to the bank in the loan account. The underlying principle is that funds belonging to someone else, but standing in the name of the borrower, should not be used to satisfy the borrower’s dues to the bank. For example, in the case of a proprietary firm, the accounts in the borrower’s personal name and the firm’s name are considered to be in the same right. In the case of a partnership firm, the firm’s accounts and the personal accounts of the partners cannot be considered to be in the same right, except if the partners have specifically undertaken joint and several liabilities for the firm’s debt with the bank.

- The right of set off can be exercised only in respect of debts already due for payment, and not for future debts or contingent debts.

- The exact amount of debt due should be ascertainable. For instance, if X stands guarantee for a loan due from Y to the bank, X’s liability cannot be exactly determined till Y defaults. Therefore, till X’s liability is determined, the bank cannot set off the credit balance in X’s deposit account against the dues.

- The bank cannot exercise the right of set off if there is an express contract which is inconsistent with such a right.

- The bank can combine the accounts of the customer at various branches of the same bank at its discretion for exercising the right.

- In case of a garnishee order19 against a customer, the bank can first exercise its right of set off and then surrender the remaining amount to the judgment creditor.

The bank has another right—the right of appropriation of payments received from the borrower, where the latter has taken more than one loan from the bank, or has more than one account with the same bank. This right is governed by Sections 59 to 61 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, by which the bank can appropriate payments received to debts that have already fallen due for payment. Payments should first be appropriated towards interest and then towards principal repayments, unless there is a contract to the contrary. The rule derived from the famous Clayton’s case20 is of substantial practical application to banks. According to this landmark ruling, credits to loan accounts would adjust or set off debits in the chronological order. Further, in case of death, retirement or insolvency of a partner of a firm, the then existing debt of the firm is set off by subsequent credit inflows to the account. The bank thus loses its right to claim the debt from the assets of the outgoing partner, and may have to suffer a loss if the remaining debt cannot be recovered from other partners. Hence, to prevent the operation of the rule in Clayton’s case, the bank closes the existing account of the firm, and reopens in the name of the reconstituted firm.

BOX 6.4 SOME CASE LAWS SUMMARIZED–BANKERS’ LIEN AND SET OFF

In Vijay Kumar vs M/s Jullundur Body Builders, Delhi and others [AIR 1981, Delhi 126], Syndicate Bank issued a bank guarantee on behalf of its customer. As security for the bank guarantee, the customer deposited two fixed deposit receipts, duly discharged, with a covering letter stating that the deposits can remain with the bank as long as any amount was due to it from the customer. However, the bank officer made an entry on the reverse of the deposit receipts, implying that the deposits served as security only during the validity period of the bank guarantee. When the bank guarantee was discharged, the bank claimed its right of general lien on the deposits. However, the Delhi High Court ruled that the bank had only particular lien since the officer’s comments on the reverse of the deposit receipts were explicit and specific, while the covering letter from the customer was on a printed format.

However, the Supreme Court had a different view in the same case. In AIR 1992, SC 1066, the Supreme Court upheld the right of bankers’ lien and right of set-off, holding that these are of mercantile custom and are judiciously recognized. It was held that ‘The bank has general lien over all forms of securities or negotiable instruments deposited by or on behalf of the customer in the ordinary course of banking business and that the general lien is valuable right of the banker judicially recognized and in the absence of an agreement to the contrary, a Banker has a general lien over such securities or bills received from a customer in the ordinary course of banking business and has a right to use the proceeds in respect of any balance that may be due from the customer by way of a reduction of customer’s debit balance. In case the bank gave a guarantee on the basis of the two FDRs it cannot be said that a banker had only a limited particular lien and not a general lien on the two FDRs. It was hence held that what is attached is the money in deposit amount. The banker as a garnishee, when an attachment notice is served has to go before the court and obtain suitable directions for safeguarding its interest’

In Brahmayya vs. K P Thangavelu Nadar [AIR 1956, Madras 570], the Madras High Court has explained the rationale thus: ‘When goods are deposited with or securities are placed in the custody of a bank, it would be correct to speak of rights of the bank over the securities or goods as lien, because the ownership of the goods or securities would continue to remain in the customer. But when moneys are deposited in a bank as fixed deposit, the ownership of the moneys passes to the bank and the right of the bank over the money lodged with it would not be really a lien at all. It would be more correct to speak of it as a right of set off or adjustment’

The court can interfere in the exercise of the Bank’s Lien. In Purewal and Associates and another vs. Punjab National Bank and others (AIR 1993, SC 954) the debtor failed to pay dues to the bank which resulted in denial of bank’s services to him. The Supreme Court of India ordered that the bank shall allow the operation of one current account which will be free from the incidence of the Banker’s lien claimed by the bank so as to enable the debtor to carry on its day to day business transactions etc. and the liberty was given to bank to institute other proceedings for the recovery of its dues.

In City Union Bank Ltd.vs.Thangarajan (2003)46 SCL 237 (Mad), certain principles with respect to Banker’s lien were reiterated. The bank gets a general lien in respect of all securities of the customer including negotiable instruments and FDR s, but only to the extent to which the customer is liable. If the bank fails to return the balance, and the customer suffers a loss thereby, the bank will be liable to pay damages to the customer. In the quoted case the Court based its decision on the principle that in order to invoke a lien by the bank, there should exist mutuality between the bank and the customer i.e., when they mutually exist between the same parties and between them in the same capacity. Retaining the customer’s properties beyond his liability is unauthorized and would attract liability to the bank for damages.

Banker’s Lien is not available against Term Deposit Receipt in Joint Names when the debt is due only from one of the depositors In State Bank of India vs. Javed Akhtar Hussain and others, AIR 1993, Bom.87, the bank obtained a decree against applicant and non-applicant who stood as a surety to the non-applicant No.1. After a decree was passed, the nonapplicant No. 2 deposited a sum of `32,793 in TDR No. 856671 with the appellants in joint names of himself and his wife in another branch of the same bank. They were also having RD account. The applicant bank retained lien on both these accounts without exhausting any remedy against non-applicant No.1. The Court held that the action of keeping lien was a sort of suomuto act exercised by the Bank even without giving notice to the non-applicant No. 2 and his wife. The applicant could have moved the court for passing orders in respect of the amounts invested in TDR and RD accounts. However, it was ruled that the action of the bank in keeping lien over both these accounts was unilateral and high-handed.

A banker’s right of set off cannot be exercised after the money in his hands has been validly assigned or in any case after he has been notified of the fact of an assignment.(Official Liquidator, Hanuman Bank Ltd. vs. K.P.T. Nadar and Others 26 Comp.Cas. 81)

In Punjab National Bank vs. Arunamal Durgadas, AIR 1960 Punj.632 State Bank of India vs. Javed Akhtar Hussain, AIR 1993 Bombay, 87, certain essentials to exercising the right of set off were indicated. It was established that: (1) Mutuality is essential to the validity of a right of exercising set-off (2) It must be between the same periods.

Mortgage: Section 58 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882, defines a mortgage as ‘the transfer of interest in specific immovable property for the purpose of securing the payment of money advanced or to be advanced by way of loan, on existing or future debt or the performance of an engagement, which may give rise to a pecuniary liability’.

The transferor of the property is the ‘mortgagor’. The entity to whom the transfer takes place is the ‘mortgagee’. The document through which mortgage takes effect is the ‘mortgage deed’.

From the definition, it follows that there are two important ingredients to a mortgage—(a) the transfer of interest in the mortgaged asset, and (b) the transfer is to create a security for the amount paid or to be paid by the bank as loan.

The following points about mortgage are to be noted:

- Transfer of ‘interest’ differs from ‘sale’ where there is a transfer of ownership. Transfer of interest implies that only some rights of the owner are transferred, and some are retained with the owner. For example, the right of redemption of mortgaged property is retained with the owner. Once the amount due to the bank (principal and interest) is repaid, the interest in the property is restored to the owner. Similarly, the bank, as the mortgagee, does not become the absolute owner due to the transfer of interest, but only has the right to recover its dues from selling the mortgaged property.

- Every co-owner or joint owner of the property is entitled to mortgage his share of the property.

- The mortgaged property should be specific, and identified by features such as location, size, boundaries and distinguishing features.

- Transfer of property in discharge of a debt is not a mortgage. Transfer of interest in the property should be to secure an existing or future loan, or to ensure the performance of an obligation which results in monetary obligation.

- It is not necessary that the actual possession of the property be transferred to the bank.

The Transfer of Property Act recognizes six types of mortgages. They are as follows:

- Simple mortgage [Section 58(b)]. In this type of mortgage, the bank is not in possession of the property, but registration is mandatory irrespective of the amount of loan for which the property is the security. Further, the bank is not entitled to any income out of rents or profits of the mortgaged property, and the bank cannot sell the property for recovering its dues without the permission of the court.

- Mortgage by way of conditional sale [Section 58(c)]. Banks do not prefer this type of mortgage since there is no personal covenant for debt service, and the bank cannot look to other assets of the mortgagor if there is a shortfall in security coverage. Under this transaction, there is an ‘ostensible’ (not real) sale of the mortgaged property to the bank. If the debt is not repaid on due date, the bank can approach the court for foreclosure, which implies causing the borrower to lose his right of redemption of the property.

- Usufructuary mortgage [Section 58(d)]. Banks do not prefer this mode of mortgage, because, as in the earlier case, there is no personal covenant on the borrower for debt service. However, the bank is in ‘legal possession’ of the property, by which it can receive rent and profits from the property and appropriate them to the debt payable by the borrower. If the borrower fails to redeem the property within 30 years through the court, the bank becomes the absolute owner.

- English mortgage [Section 58(e)]. There is an absolute transfer of property to the bank, with the provision that full repayment of the debt will entitle the borrower to redeem the property. In case of security shortfall, the bank can look to the personal assets of the borrower for full liquidation of its dues.

- Equitable mortgage or mortgage by deposit of title deeds [Section 58(f)]. This is by far the most preferred type of mortgage by banks in India. Though this mortgage can be effected only in the towns notified by the government, the territorial restriction is applicable not to the location of the property, but where the title deeds are delivered by the borrower to the bank. ‘Title deeds’ are documents or instruments that enable the owner of the property to enjoy the right to peaceful and absolute possession of the property described in the documents. To create this mortgage, the owner or joint owners of the property should personally deposit the original title deeds with the bank at the notified centres, with the intention of creating a security for the loan taken from the bank. There are no registration or stamp charges involved in many Indian states and creation of the mortgage is least time consuming. The risks for the bank could arise in respect of the authenticity of the documents and the borrower’s standing in respect of the property. For example, if the borrower mortgages the property for which he holds the original title deeds as trustee, the claim of the beneficiary under trust will prevail over any equitable mortgage. The bank should also conduct a physical inspection of the property and verify the authenticity of factors like the boundaries and market value before accepting the security.

Box 6.5 summarizes some Supreme Court decisions in respect of equitable mortgages.

BOX 6.5 EQUITABLE MORTGAGE: WHAT THE SUPREME COURT DECIDED

There are three important requirements for an equitable mortgage: (a) debt, (b) deposit of title deeds of the property and (c) the intention that the title deeds will be the security for the debt.

In K J Nathan vs. S V Maruthi Rao (ATR 1965, SC 430), it was opined that, ‘Whether there is an intention that the deeds shall be security for the debt is a question of fact in each case… there is no presumption of law that the mere depositing title deeds constitutes a mortgage, for no such presumption has been laid down, either in the Evidence Act or in the Transfer of Property Act’…

In United Bank of India vs. Lekheram sonaram and comp.(AIR 1965, SC 1591), it was stated that ‘But if the parties choose to reduce the contract to writing (with all terms and conditions) such document requires registration under Section 17 of Indian Registration Act 1908. If a document of this character is not registered it cannot be used in evidence at all and the transaction itself cannot be proved by oral evidence either’.

Further, in Deb Dutt Seal vs. Raman Lal Phumsa (AIR 1970, SC 659), the Supreme court ruled… When the debtor deposits with the creditor, title deeds of his property with interest to create a security, the law implies a contract between the parties to create a mortgage and no registered instrument is required under Section 59 as in other classes of mortgage.

- Anomalous mortgage [Section 58(g)]. A mortgage that does not fall into any of the categories discussed above is an anomalous mortgage. Such mortgages can also be combinations of two types of mortgages, such as a combination of simple and usufructuary mortgages, depending on the custom and local usage.

Charge: This is a word that can commonly be used to describe any form of security for debt, whether the borrower is an individual, partnership firm, private or public limited company or the government.

More specifically, charges registered, under the Companies Act, 1956 include rigorous provisions, and can generally be classified into a ‘fixed charge’ and a ‘floating charge’.

A ‘fixed charge’ (not to be confused with ‘fixed assets’) is a specific charge over designated properties of the company. It gives the bank the right to sell the assets and appropriate the sale value to the debt due from the company.

A ‘floating charge’ (a) ‘floats’ over the present and future property of the company (including those under fixed charge) and is not attached to any specific asset or assets; (b) does not restrict the company from selling the assets under charge or assigning them as security for loans from other parties; and (c) could crystallize into a fixed charge upon the happening of an event or contingency, such as liquidation of the company. It is important to note that when the floating charge becomes fixed, it constitutes a charge on all properties and assets belonging to the company, and gains seniority over all subsequent fixed charges, unsecured creditors and money advanced to the liquidator.

It is, therefore, evident that, in order for the bank to be the senior creditor, it will have to ensure seniority in claims over the bank’s assets as well. This purpose is achieved by registering the bank’s charge with the Registrar of Companies under Section 125 of the Companies Act, 1956. Such registration of charge will have to be done within 30 days of execution of the loan agreement, and can be extended up to 60 days with a penal provision.

What are the consequences of non-registration of charge by the bank? In the event of the company going into liquidation, the bank’s debt, otherwise ranked senior to all other creditors’ claims, will now be treated as unsecured, and will rank low as an unsecured creditor at the time of settlement of claims. It is to be noted that in spite of non-registration of charge, the bank’s debt is recoverable and the securities are enforceable, as long as the company is a going concern. The bank gets ranked as an unsecured creditor only in case of company liquidation. A more serious consequence would be when a junior creditor moves up to senior position at the time of enforcement of securities, merely by virtue of having filed its charge with the registrar of companies before the senior creditor did. This is in accordance with the provisions contained in Section 126, which clarifies that notice of charge registered by the bank under Section 125 will be reckoned from the date of registration and not from the date of creation of the charge. It is also mandatory that every time there is a change in the loan agreement, a modification charge is filed with the registrar of companies within 30 days of such modification taking effect.

The bank should also verify prior fixed and floating charges on the assets charged to it by the borrowing company before specifying the security backing in its loan agreement. For example, if the borrowing company had made a debenture issue, secured by floating charge on all the company’s assets, with a specific clause prohibiting creation of any charge senior to ranking on par with debenture holders, then the bank cannot gain a senior creditor position in spite of registering its charge on time. If the bank still finds lending to this company profitable, it should stipulate suitable covenants that would compensate for a likely shortfall in security backing for its advances to the company.

Box 6.6 presents an illustrative checklist of the precautions bankers should take while lending to a company.

A detailed description of the provisions of law relating to registration of charges can be found in Sections 124 to 145 of the Companies Act, 1956.

BOX 6.6 ILLUSTRATIVE CHECKLIST FOR BANKS LENDING TO COMPANIES

- A company is a legal entity. Check the Certificate of Incorporation. When and where was the company incorporated? Where is the Registered Office? This is important since all communication to the company should be addressed to the registered office.

- Ask for the Certificate to commence business. Any contract entered into by the company before this date will not be binding on the company, nor can the company exercise its borrowing powers before this date.

- What are the objects of the company’s incorporation as embodied in its Memorandum of Association? Is the present line of business in keeping with the objects?

- Scrutinize the Memorandum of Association. The capital clause indicates how much equity the company can mobilize either from its promoters or the public. Are the capital projections of the company in keeping with the boundaries set down in this clause?

- Are the company’s lines of business as defined in the Memorandum? If there are deviations, have the necessary changes been made in the Memorandum in the manner prescribed by Company Law? Any attempted departure from the clauses will be ‘ultra vires’, even if assented to by all board members. The object clause of the Memorandum usually contains a blanket clause—‘and to do all such other things as are incidental or conducive or as the company may think conducive to the attainment of the above objects’. Companies tend to construe these words as widening the scope of the object clause. For example, offering guarantee for the loans availed by another company under the plea that such an act would widen the scope of achieving the main objects of the company, would not be expressly permitted by the Memorandum. If the bank overlooks these lapses, it could run a risk of loss in case of default.

- What is the composition of the Board? Are there sufficient independent directors? How are decisions made?

- Scrutinize the Articles of Association. Are the directors acting within their powers? Do they have the capacity to borrow from the bank?

- What is the limit up to which the company can borrow? This is different from the borrowing powers of directors. While borrowing powers of directors can be amended by suitable resolutions, the borrowing power of the company would be embedded in the Articles of Association, and cannot be violated.

- Refer to the Articles of Association to ensure that the officials executing loan documents are indeed authorized to do so.

- Ask for copies of all relevant resolutions passed at general body meetings—such as for borrowing, mortgaging property, etc.

- Ensure creation/modification of charge on the property of the company as prescribed by the Companies Act. Note that a registered charge takes priority over an unregistered charge, registered charges take priority from date of creation (though constructive notice arises from date of registration), and a registered floating charge with no restrictive clause ranks after a subsequent (or prior) specific registered charge.

- If a company is named as guarantor for a loan, scrutinize the Memorandum and Articles of Association to ascertain whether the company is authorized to give such guarantees.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- The features of each of the credit delivery modes in India are designed to help the borrower carry on operations without interruption, simultaneously facilitating recovery of the debt for the lending bank. The terms and conditions, the rights and privileges of the bank and borrower differ in each case.

- Under the cash credit system, the bank specifies a credit limit for the borrower. The credit limit is backed by prime, securities in the nature of inventories or book debts or receivables, and collaterals and guarantees, if the bank so insists. To usher in discipline in the funds utilization of large borrowers, and instil efficient funds management in banks, the loan system for delivery of bank credit had been introduced in the mid 1990s. The system stipulates that the assessed working capital requirements of the borrower will be delivered as two components—a loan component, called the WCDL, constituting not less than 80 per cent of the assessed credit limit, with the cash credit component forming the remaining 20 per cent.

- The bank may grant an overdraft to satisfy urgent credit requirements of a borrower against a collateral security or personal guarantee. The contract of an overdraft can be express or implied.

- Bill financing’ occurs when BOE drawn by the borrower or by counter parties on the borrower are discounted by the bank. Bills purchased and discounted by banks are in the form of clean bills, documentary bills or supply bills.

- If a loan is not backed by any tangible security; except the personal guarantee of the borrower himself or a third party, the loan is classified as ‘unsecured’. Secured loans are backed by tangible assets in the form of ‘floating’ or ‘fixed’ assets. Observing some basic safeguards, such as (a) ensuring adequate margin; (b) ensuring easy marketability and (c) proper documentation while accepting assets as securities would help the bank recover most of its dues in the event of default

- Though commonly used by bankers, ‘security’ is not defined in any act. Securities accepted by banks fall into the categories of (a) pledge, (b) hypothecation, (c) assignment, (d) lien, (e) mortgage, and (f) charge.

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

- Rapid fire questions

Answer ‘True’ or ‘False”

- Each credit delivery mode is designed to help the borrower carry on operations without interruption.

- For consumer loans, the assets purchased under the loan form the security.

- Working capital loans are granted only against inventory of the borrower firm.

- Overdrafts can also be unsecured advances.

- Commercial bills are money market instruments.

- Clean bills are always supported by documents of title to goods.

- The drawee of a bill is the seller of goods.

- In India, the base rate has replaced the MCLR as the procedure for loan pricing.

- ‘Hypothecation ‘ is defined under the NI Act.

- If a borrower has projected negative net working capital, banks will grant working capital finance to the borrower.

Check your score in Rapid fire questions

- True

- True

- False

- True

- True

- False

- False

- False

- False

- False

- Fill in the blanks with appropriate words and expressions

- Banks’ right of set off enables it to adjust the ————— balance in one account of a customer with the ————— Balance in another account of the same customer.

- ————— is the right of a bank to retain the securities given by a borrower until the debt is fully repaid

- If a loan is not backed by any tangible security, the loan is classified as —————.

- ————— mortgage is the most preferred type of mortgage by banks in India.

- Mortgages are described in the ————— Act.

- Goods under ‘hypothecation’ are held by the —————.

- ————— bills do not fall under the NI Act. They are debts ————— in favour of the bank

- The components of the MCLR are —————.

- ‘Drawee’ bill financing has the effect of financing ————— of the —————.

- There are two forms of ‘assignment’, ————— and ————— assignment.

- Expand the following abbreviations ( in the context of this chapter)

- MCLR

- TOP (Act)

- BOE

- WCDL

- CC

- NI (Act)

- Test your concepts and application

- Which of the following statements are true?

- Documents of title to goods are negotiable instruments.

- Supply bills are BOE

- A bill of exchange is an unconditional direction to the drawer to pay a certain amount.

- Bills purchase facility is granted by the bank in the case of DP bills.

- Endorsement means signing the bill of exchange for transfer.

- Documentary bill means a bill accompanied by documents of title to goods.

- Which of the following statements are false?

- Simple mortgage is created by an instrument in writing.

- Mortgage by deposit of title deeds is always required to be registered.

- All successive mortgages created over a property will rank equally at the time of liquidation.

- The owner of the goods cannot pledge the goods

- Hypothecation is an implied pledge in cases where constructive possession of goods is given.

- ‘Charge’ is any form of security for debt.

- Can you list the differences between ‘charge’ and ‘mortgage’?

- J Industries Ltd wants to fund its new capital acquisition and working capital through bank finance. The cost of the expansion plan is given below:

- Plant and machinery: ₹500 lakh

- Building and site development: ₹75 lakh

- Other expenditure: ₹25 lakh

The company requires current assets of ₹620 lakh during this period, the split up for which is as follows:

Inventory: ₹300 lakh Receivables: ₹180 lakh Cash and others: ₹140 lakh Fill in the following table to assess the structure of working capital finance, if current liabilities amount to ₹70 lakh and the bill finance required is ₹40 lakh. Assume the bank wants a margin of 25 per cent for all the modes of financing it extends to the borrower.

- Which of the following statements are true?

Margin on capital expenditure will be @ 25 per cent on long-term assets.

- Long-term assets will include only specific immoveable property being considered for expansion =

- Margin = 0.25 × (A) 5

- Bank finance for capital expenditure = (A) – (B) =

- Permissible bank finance (PBF) for working capital = 0.75 × (current assets – current liabilities) =

- Margin for working capital = ₹620 less (D) Structuring limits

- WCDL = 0.8 × (D)

- CC = 0.2 × (D) = amount of CC available for inventory

- Balance of inventory to be financed = inventory – (G) =

- Amount of WCDL used for bills financing = ₹40 lakh

- Hence, WCDL available for funding remaining inventory and other debtors = (F) – (I) =

TOPICS FOR FURTHER DISCUSSION

- Take up the financial statements of any Indian company and try to do a credit appraisal, placing yourself in the shoes of the credit officer assessing the company’s financial health and other factors. Under what conditions would you sanction credit limits to the company? (Tip: Do an analysis of risk factors).

- What would be the special covenants you would incorporate while lending to SMEs in India?

SELECT REFERENCES

- Indian Institute of Banking and Finance, 2005, Legal Aspects of Banking Operations, chapters, 12–19, Macmillan India Ltd, 197–285. (N. Delhi)

- Supreme Court of India Web site—http://supremecourtofindia.nic.in

- Varshney, P R, 2004, Banking Law and Practice, Chapters 15–18, Sultan Chand & Sons, 4.18–4.129. (N. Delhi).

ANNEXURE I

TYPES OF BORROwERS AND MODES OF LENDING

Who Can Borrow from Banks?

Typically, there are six types of borrowers to whom banks can lend. They are as follows:

- Individuals. Any individual who is competent to enter into a contract.21

- Partnership firms. These are firms governed by the Indian Partnership Act, 1932. The most relevant clause for banks is Section 19 of the act, which deals with the implied authority of a partner as an agent of the firm, and also states that a partner cannot mortgage the firm’s property unless expressly authorized to do so.

- Hindu Undivided Family (HUF). This is a law created by custom and has to be interpreted according to two prevalent schools of thought—the Dayabhag and Mitakshara. Succession among Hindus is governed by the Hindu Succession Act, 1956. The bank should ensure that the ‘Karta’ of a HUF borrows only for the joint family’s benefit. Similarly, all adult members are jointly and severally liable for borrowings.

- Companies. These are to be registered under Section 11 of the Companies Act, 1956. The bank has to verify that the ‘Memorandum of Association’ of the company permits it to carry on the business for which credit limits are sought. Similarly, the borrowing powers of the company are determined by the articles of association.

- Statutory corporations. These are governed by the acts under which they were established.

- Trusts and co-operative societies. Trusts are governed by the Indian Trusts Act, 1882, and the bank should ensure that the credit is within the legal framework. Clubs, societies and co-operative societies have to be registered under the Companies Act, 1956, the Societies Registration Act or the Co-operative Societies Act. The bank should examine the by-laws and other applicable regulations to determine the eligibility of these organizations to seek bank credit.

In this section, we will look at the methodologies adopted by Indian banks to assess the various types of credit requirements of borrowers. Recognizing the need for banks to be competitive, both in the domestic and international markets, the RBI has now given banks the autonomy to evolve their own internal methods for appraisal and assessment of credit requirements. While credit appraisal closely follows the framework presented in the previous chapter, the methods of lending have been customized for various categories of borrowers, depending on the purpose, their contribution to the economy and their developmental needs.

Banks in India have traditionally been lenders for working capital needs of borrowers, with the financial institutions having been slated for the role of term lenders. The composition of liabilities and assets of banks and financial institutions, as two different categories of financial intermediaries, also varied to suit the purpose for which they were formed. The financial sector reforms and progressive privatization, consolidation and globalization of the banking sector have now led to the blurring of the distinction between banks and financial institutions. In the present context, Indian banks have almost taken over the functions of the financial institutions, and have also made a foray into financial services in a big way.

Banks are now are expected to lay down, through their Boards, transparent policies and guidelines for credit dispensation, in respect of each broad category of economic activity, keeping in view the credit exposure norms and various other guidelines issued by the RBI from time to time. Some of the currently applicable guidelines and practices are detailed in the following paragraphs.

Working Capital Finance

Banks generally use one of the following methods to assess the working capital financing requirements of borrowers.