CHAPTER TWO

Monetary Policy—Implications for Bank Management

CHAPTER STRUCTURE

Section II Application of the Monetary Policy Tools in India

Section III Monetary Policy Tools in Select Countries

Annexure I, II and III (Case study)

KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM THE CHAPTER

- Understand the role of central bank and monetary policy in economic growth.

- Understand why banks hold reserves.

- Learn about the tools of monetary policy.

- Understand how the monetary policy impacts banking operations and management.

SECTION I

BASIC CONCEPTS

A Macroeconomic View

The primary objective of a country’s government is to achieve economic stability and growth. Hence, macroeconomic policies will typically target and monitor three basic indicators: prices, employment and balance of payments. Such monitoring is done through two fundamental pillars of macroeconomic policy—the fiscal and monetary policies.

The fiscal policy targets two major parameters: tax receipts and government expenditure. While taxes are garnered through the mechanism of tax rates that can be varied by the government from time to time, government expenditure is planned and monitored through the annual and long-term plans formulated by the government.

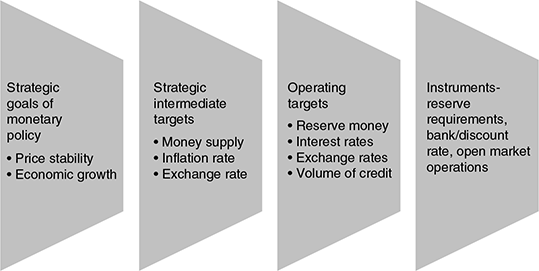

The monetary policy targets the vital parameters that determine the liquidity and capital formation in the economy, as seen in the pictorial depiction given in Figure 2.1, and is formulated by the Central Bank of the country.

In the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes focussed attention on the use of fiscal policy to manage business cycles, and this emphasis continued well into the 1960s. However, Keynes’ theory could not provide satisfactory answers to the worldwide stagflation of the 1970s. Further, some governments, for political reasons, were more inclined to run deficits than surpluses. The rapid changes in the economic and business environments could not be adequately supported by legislative processes or policies. In contrast, the monetary policy, formulated by the central banks, appeared more insulated from political pressures, and hence was seen as being able to impose more economic restraint. Since the 1980s, policy makers have come to rely more on the monetary policy to manage the business cycle and achieve price stability.

Theoretically, monetary policies rest on a simple identity that economists know too well:

In this equation, M equals money supply, V the velocity or turnover of money, P the price level and Q the quantity of output. Simply stated, the economic output or the GDP, measured in monetary terms, equals the amount of money in circulation times the frequency with which the money changes hands. Hence, in essence, both sides of this equation represent the nominal GDP.

This deceptively simple-looking equation, however, raises pertinent questions.

- What is money?

- What determines money supply?

- How do we measure money supply?

- What should be the basis of monetary policy?

A deeper understanding of and clarity in respect of the above concepts will help effective use of the equation for policy formulation.

Money ‘Money’ is generally defined as anything that people are willing to accept in payment for goods and services or to pay off debts—in other words, money is generally an acceptable medium of exchange, usable by all, with standardized quality, durable, divisible and easy to transport. ‘Currency’, therefore, is undeniably ‘money’.

Money has other characteristics as well.

- It is a ‘store of value’. This implies that money is a measure of ‘value’, and can be held for future use. However, in times of inflation, ‘money’ retained as ‘currency’, could lose ‘real’ value.

TEASE THE CONCEPT

What is the difference between ‘money’—defined as currencies—and an alternative financial asset, say a money market instrument or physical assets such as real estate?

- It is a ‘unit of accounting’.

- It is a ‘standard for deferred payment’. This implies that for a transaction done today, payment could be made later.

- It is the ‘means of final payment’. This is a characteristic unique to money.

TEASE THE CONCEPT

Money Supply Money supply is the total quantity of money in the economy. While we will look at the various measurement parameters adopted by central banks a little later, in the narrow sense, ‘money supply’ is defined as the currency in circulation in the economy plus demand deposits1 with banks.

Only the central bank has the power to authorize creation of ‘currency’ (notes and coins) that we carry around in our wallets. Banks, however, can ‘create’ deposits (and credit).

How are banks able to create deposits? The simple example given in the Box 2.1 illustrates this iterative process.

Why do banks not lend all the deposits that they get? Banks are obligated to pay depositors as and when they demand repayment of their deposits. Any demur on the part of a bank to repay deposits would cause panic among the depositors, and the bank would be dubbed unsafe. Hence, reserves ensure ‘liquidity’ for the bank. Most central banks, therefore, insist that a portion of the liabilities of banks be kept as ‘reserve’, either as cash or balances with the central bank or as near cash securities.

BOX 2.1 HOW BANKS CREATE DEPOSITS/CREDIT—THE CONCEPT OF THE MONEY MULTIPLIER

Let us look at a highly simplified example.

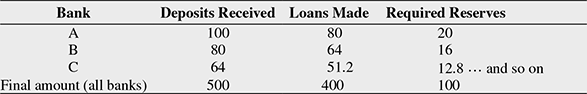

Suppose, an individual X deposits ₹100 of currency into his demand deposit account in Bank A. Although Bank A is obligated to repay ₹100 on demand to X or any other third party designated by X, the Bank, for commercial reasons, will probably lend a sizeable portion—say ₹80 of the deposit to another person, say Y. Now, X has a demand deposit of ₹100 and Y has currency worth ₹80. In other words, Bank A has increased the ‘money supply’ to ₹180 on a base of ₹100. In this case, ₹100 is called the ‘monetary base’. The iterative process starts here. Y will either deposit the loan ₹80 in his Bank B or pay to a third party who will, in turn, deposit the amount with Bank B. In any case, a new demand deposit of ₹80 is created. If we assume that all banks lend 80 per cent of the amount they take in as demand deposits and all money thus lent is redeposited in full into a bank, Bank B will lend ₹64 to say, Z, who in turn, deposits this amount with Bank C. The iterations can be represented as follows:

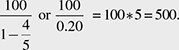

The process can be recognized as a Geometric Progression (GP) whose summation would be

Let us now sum up our calculations as follows:

It is thus seen that the initial deposit of ₹100 has created ₹500 deposits or 400 of credit in the banking system. In other words, ‘money supply’ can be calculated by multiplying the monetary base by the inverse of the ‘leakage’, which is the proportion of deposits that the banks have retained with themselves. The inverse of the ‘leakage’, in this case 5, is called the ‘money multiplier’.2

TEASE THE CONCEPT

- What happens to the money multiplier if the leakage is (a) 25 per cent or (b) 10 per cent?

- What will be the impact on money supply if, instead of depositing the entire loan amount into another bank, X, Y, Z and others in the example above, retain 5 per cent of the loan amount as cash?

- What is the significance of ‘cashless’ transactions in the economy? How do they benefit the economy?

In most countries, the central bank sets the ‘reserve requirements’, thus, placing a cap on the ability of banks to create credit. Although banks almost always hold reserves in excess of statutory requirement, the size of this excess is quite small. Excess reserves maintained with the central bank impose a cost on banks that equals earnings foregone on the amount by which required reserves exceed the reserves that banks would voluntarily hold in order to conduct their business. This practice of setting aside a portion of the bank’s deposits to meet liabilities is also called ‘fractional reserve banking’.3

Therefore, it is evident that the size of the monetary base and the level of leakage determine the money supply in the economy. The central bank can control the monetary base and strongly influence the leakage.

A typical central bank’s balance sheet has the following components:

| Liabilities | Assets |

|---|---|

| Currency (about 80 per cent) | Government securities (about 80 per cent) |

| Deposits from banks (about 20 per cent) | Foreign exchange (about 10 per cent) |

| (these are the reserves maintained by banks) | Gold (about 10 per cent) |

The total liabilities of the central bank constitute the ‘monetary base’.

Measuring Money Supply There are three broad measures economists use when looking at the money supply: M1, a narrow measure of money’s function as a medium of exchange; M2, a broader measure that also reflects money’s function as a store of value; and M3, a still broader measure that covers items regarded as close substitutes of money. The indicators that measure money supply, though conceptually similar, differ in nomenclature and composition from country to country. Basically, all countries measure their money supply through a ‘narrow money’ and ‘broad money’ definition. While the narrow money definition restricts itself to money held for immediate transactions, such as notes and coins with the public, and transaction accounts (e.g., demand deposits) held with banks, the broad money concept includes time deposits as well as other forms of money supply defined by the central bank.

For example, in the United Kingdom, narrow money is termed M0—this is simply the total stock of notes and coins in circulation plus the commercial bankers’ operational deposits held with the Bank of England. Broad money is termed as M4 and includes M0 plus sterling deposits held by the UK residents at bank and building societies. Broad money (or M4), therefore, comprises both the deposits lodged into accounts by people wanting to save, together with deposits created by commercial banks and building societies through their lending activities.

In the United States, monetary measures are defined as follows:

- M0: The total of all coins and paper cash in circulation.

- M1: M0 + the amount in checking or demand deposit accounts.

- M2: M1 + other various savings account types, money market accounts and certificate of deposit (CD) accounts of below USD 100,000.

- M3: M2 + all other CDs, deposits of eurodollars and repurchase agreements.

Central Bank Tools to Regulate Money Supply

Most central banks use three primary tools to influence money supply in the economy.

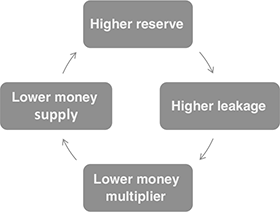

Tool 1 : Reserve Requirements

First, the central bank determines ‘reserve requirements’. We have seen in the simple example in the previous box that the ‘leakage’ or ‘reserves’ impact the credit creation ability of banks. When the central bank decreases the reserve requirement, the money multiplier increases, and, thus, money supply expands. Remember that the money supply identity is the product of the monetary base and the money multiplier.

Conversely, by increasing the reserve requirement, the central bank causes the money multiplier to fall, thus contracting money supply. Alteration in the reserve requirement can have an immediate impact on the availability of credit in the economy, through effecting a change in the money multiplier.

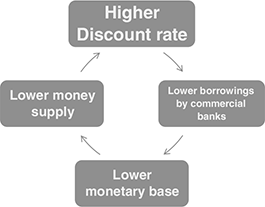

Tool 2: Bank/Discount rate

The second tool is the ‘discount rate’ or ‘bank rate’. Banks can borrow directly from the central bank through the ‘discount window’. The term ‘discount window’ originated with the practice of banks selling loans or shortterm notes to the central bank at a discount. Such loans or ‘refinancing’ from the central bank add directly to the existing monetary base by increasing bank reserves thus leading to an expansion in money supply. The central bank periodically determines the size of the discount—which is called the ‘discount rate’. The ‘discount rate’ is also called the ‘bank rate’ since this is the rate at which banks borrow from the central bank. By lowering this rate, the central bank makes borrowing more attractive to banks, and by increasing this rate and making funds dearer, it attempts to discourage banks from borrowing. Typically increase or decrease of the bank rate is considered a ‘signal’ for banks to raise or lower their interest rates. Higher interest rates are expected to discourage credit growth in the economy, since it is assumed that borrowers will borrow less or desist from borrowing when interest rates rise. Therefore, in such cases, a hike in the bank rate is designed to restrict money supply.4

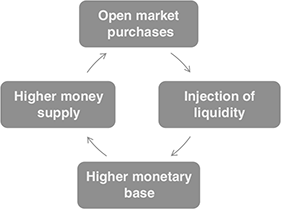

Tool 3: Open Market Operations (OMO)

The third, and in many cases, the most important tool of the central bank is ‘open-market operations’ (OMOs). The central bank influences the money supply in the economy by buying or selling bonds and other financial instruments in the open market. When the central bank, say, buys government securities from banks and other parties, it injects liquidity into the economy and, thus, increases the monetary base. When the central bank sells securities, it absorbs liquidity and, thus, reduces the monetary base. OMOs are the primary policy instruments of central banks of developed countries, and are becoming increasingly important in developing countries. OMOs are a form of indirect control over the reserves in the banking system, as contrasted with the direct control exercised by, say, the cash reserve ratio (CRR). Developing indirect controls is vital to the process of economic development. As markets in globalized economies grow and expand, market forces seek to unleash their potential and direct controls start losing their efficacy. However, for OMOs to become an important part of the monetary policy, market infrastructure needs to be revamped, and the existing tools of monetary policy would need to undergo some modifications.

It is, therefore, evident that the central bank can regulate the money supply in the economy by changing the money multiplier (changing the reserve requirements) or by changing the monetary base (altering bank rates or through OMOs).

To summarize, the three tools of Monetary Policy operate as shown in Table 2.1.

TABLE 2.1 OPERATION AND IMPACT OF THE THREE TOOLS OF MONETARY POLICY

The Impact of OMOs on Other Tools of Monetary Policy

OMOs can typically be conducted in an ‘active’ or ‘passive’ manner. Under active OMOs, the central bank aims at a predetermined quantity of reserves, and allows the interest rates (the price of these reserves) to fluctuate freely. This approach is typically used in countries where the interbank or secondary markets are less efficient. Many central banks in developed and developing countries with sophisticated markets, however, prefer the passive approach, in which a predetermined interest rate is aimed at, while allowing the reserves to fluctuate.

However, when OMOs are used as a primary policy instrument, the use of other instruments, such as discount (bank) rate and the CRR, becomes more selective and restricted. Why does this happen?

Let us first consider the bank rate. Effective OMOs also presupposes that banks’ access to central bank funds needs to be restricted. The discount rate should, therefore, be pegged at a level that makes it unattractive for banks to borrow from the central bank. In some countries, penalties and restrictive clauses are used to limit banks’ access to central bank funds. Of course, these restrictions and penalties should be flexible enough to permit short-term adjustments to banks’ liquidity when the need arises, or serve long-term emergency funding requirements in a distress situation.

Reserve requirements in the nature of CRR are considered ‘basic’ compared with the level of sophistication that OMOs demand of the market. Central bank in several developed countries impose minimal or no reserve requirements on their banks. However, reserve requirements are still used in many instances as a way of enhancing the efficacy of OMOs and regulating money supply in the short term. They are seen to be particularly useful where the central bank has to adjust banks’ liquidity rapidly or signal the need for expansion or contraction of money supply.

Central Bank Signaling Through the ‘Policy Rate’

Most central banks announce their policy stance through a single rate—the ‘Policy rate’. The Policy rate could be a target for a market interest rate (e.g., the overnight interbank market interest rate). Or it could take the form of an official rate of a central bank operation or facility, such as the Bank rate or Repo rate. Central banks running exchange rate-based regimes with no capital controls may not be able to set policy interest rates. Their exchange rates/capital flows determine the money market and other interest rates within their countries. Thus, the factors determining choice of an appropriate policy rate for central banks to signal their operational measures are the functionality and controllability of the official policy rate.

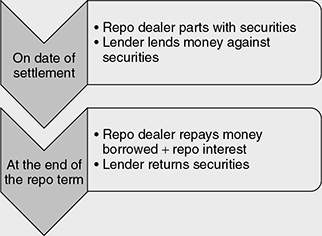

Popularity of the ‘Repo’ Rate as the Policy Rate

The widespread use of OMOs has given rise to active ‘Repo’ markets in many countries. In Repo (the abbreviated form for ‘Repurchase agreements’) transactions, securities are exchanged for cash, with an agreement to repurchase the securities at a later date. The securities form the collateral for the ‘cash loan’, and the cash form the collateral for the securities loan. The securities typically used are sovereign debt instruments, private sector debt instruments, such as commercial paper or mortgage-backed securities (MBS) or equity. As repos are short maturity (varying between overnight and 1 year) collateralized instruments, repo markets have strong linkages with other short-term markets, such as inter-bank and money markets, as also with derivatives and securities markets. Another positive feature of an active repo market is that it helps to enhance liquidity in the underlying securities, thus, leading to an active secondary market (see Box 2.2).

BOX 2.2 HOW DO REPOS WORK?

A repurchase agreement or repo, is a sale of securities for cash with a commitment to repurchase them at a specified price at a future date.

The repurchase agreement by itself is simply a collateralized loan. However, the operation resembles a spot purchase + forward sale of a bond. Representing the transaction in the form of an equation would clarify:

Now, we know that

Therefore, the earlier equation stands modified as

Since the net effect of spot purchase and sale would be null, repo is similar to ‘lending money’. See the pictorial depiction shown below.

The lenders are typically banks, money market funds, corporations, etc., while the dealers or borrowers would typically be banks or securities dealers or other market participants permitted to deal in repos. The securities are typically government securities and other securities approved by the respective regulatory authorities.

The predominant form of repo is the ‘overnight repo’, where the duration of the loan is one day. Term repos can have maturities of up to 1 year.

A ‘reverse repo’ is the exact opposite of a repo transaction. The transaction labels are usually determined from the dealer’s standpoint—hence when the dealer ‘borrows’, it is a ‘repo’ (the borrowing is at the ‘repo rate’) and if the dealer ‘lends’, the transaction is a ‘reverse repo’.

It is, therefore, clear that interest rate on repos is the rate at which the dealer compensates the lender for temporary use of money, and should be related to other money market interest rates as well. Usually, the securities pledged in a repo are valued at current market prices plus accrued interest (on coupon-bearing securities), less a small ‘haircut’ (discount) to reduce the lender’s market risk exposure. The longer the term and the riskier and less liquid the securities pledged for a repo transaction, the larger will be the ‘haircut’ to protect the lender against fall in the security price. Therefore, repos are ‘marked to market’ periodically, and if the prices of the securities pledged have dropped, the borrower would have to pledge additional collateral.

Interest income from repos is usually determined as follows:

(Note that 360 days a year is assumed by convention)

To illustrate, an overnight loan of ₹1 crore to a dealer at a repo rate of 9 per cent would yield interest income of ₹2,500 by the above formula. Under a continuing contract repo, the rate would change everyday. Hence, the interest income would be calculated for each day the funds were lent, and total interest would be paid to the lender when the contract period ends.

In such a case, the yield on repurchase agreements is represented by the following equation:

where, Yield Yr is an annualized percentage, assuming a 360 day year by convention,

RPm is the repurchase price of the securities (selling price + interest paid on the repurchase agreement),

RPs is the selling price of the securities, and

td is the number of days until maturity of the repo.

To illustrate the above, assume a bank enters a reverse repo agreeing to buy treasury bills from another market participant at a price of ₹1 crore, with an agreement to sell back the securities at a price of ₹1,00,09,000 (interest being ₹9,000) after 5 days. The yield on the repo transaction to the bank is calculated as follows:

How are repos useful as a monetary policy instrument? Their attractiveness stems from the fact that the features of repo contracts are well-suited to influence the interest rates in the economy, through impacting two of the main channels of monetary policy—controlling liquidity in money markets and signalling to markets the desired interest rate levels.

Repos and reverse repos are often used by central banks to offset short-term fluctuations in bank reserves. They are also used for adjusting large liquidity imbalances arising out of, say, large capital inflows or outflows. Repos can be used for various maturities, though they are predominantly used for short-term transactions (including overnight transactions). Outright purchases and sales of government securities in the secondary market forms an important part of the repo market in many countries.

Central banks use repo as a tool of domestic money market intervention, to control short-term interest rates on a regular basis. The repo rate then serves additionally as an important signal for the future interest rate policy of the central bank.

For repos done by central banks you have to consider that the terminology is regarded from the commercial banks’ point of view:

- Central bank repo: the central bank adds liquidity to the money markets, they buy-and sell-securities (buy securities, give cash) in the repo market, i.e. actually not the central bank but the commercial banks do repo.

- Central bank reverse repo: the central bank sells securities and thus drains liquidity from the money markets. Box 2.3 briefly outlines the effects of the recent sub-prime crisis5 on the monetary policy of the USA.

BOX 2.3 THE SUB-PRIME CRISIS AND USA’S MONETARY POLICY

The deterioration of the sub-prime mortgage market became apparent in 2006, and continued into 2007. Hedge fund failures and write downs by investment banks stemmed primarily from the collapse of the MBS market, and other related financial derivatives. However, when, as a consequence, the money markets and interbank markets were affected, the stability of short-term funding markets was shaken.

Under normal circumstances, the central bank would have injected liquidity into the banking system by resorting to open market operations and lending through its discount window. However, the Federal Reserve faced unusual challenges while attempting to use its monetary policy tools under distress conditions.

Under the OMO, the Federal Reserve injects liquidity into the market at a rate close to the target rate set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). In the open market, the Federal Reserve trades with ‘primary dealers (PDs)’, who in turn distribute the liquidity to the interbank money market, and thus to the other sectors of the economy. However, in turbulent times like those witnessed during 2007, there was a marked reluctance for banks to lend to one another in the inter-bank market, thus leading to a credit crunch and an economic slowdown.

The fed lowered its discount rate substantially to attract banks to borrow from it. While such a move should have made borrowing more attractive, under the present distress conditions banks seemed reluctant to borrow from the central bank. A possible explanation for this behaviour could be the fear of signalling to the market that the borrowing banks’ liquidity had been substantially affected, thus, reducing their ability to borrow from the market.

To offset the strain in the term funding market, the Federal Reserve introduced, at the end of 2007, a term auction facility (TAF), and followed it up with two more lending facilities in March 2008—the term securities lending facility (TSLF) and a primary dealer credit facility (PDCF)—to promote liquidity in the financial market. These facilities have been discontinued since 2011, after the crisis situation improved.

The new facilities do not increase the total reserves in the system. To maintain the federal funds rate at the target level, every TAF auction is offset by the Federal Reserve through a matching transaction in the open market.

The Monetary Ratios

We can now propose some simple ratios to determine the reserve ratios, currency ratios and money multiplier for M1 in an economy.6

- The reserve ratio can be measured as = (reserves/bank’s demand liabilities), where the bank’s reserves would be the total of the cash that banks hold in their vaults and their deposits with the central bank, and bank’s demand liabilities would include all deposits payable on demand and travellers’ cheques.7

- The currency ratio can be measured as = (currency in the hands of the public/bank’s demand liabilities), where the currency can also be calculated from the central bank financial statements as the ‘monetary base’ less ‘bank reserves’.

- The money multiplier for ‘narrow money’ can, therefore, be measured as = (M1 or narrow money/bank’s demand liabilities as defined in [1], above).

- Similarly, taking into account time liabilities and other components of ‘broad money’ would enable us to calculate the money multiplier for broad money, M3.

Other Factors that Impact Monetary Base and Bank Reserves

The central bank can change the monetary base deliberately through any of the tools described above. However, monetary base can also change due to other factors as well without any intervention by the central bank. Such factors could be:

- Refinance or Discount windows. Most central banks perform the function of a ‘lender of last resort’, i.e., they provide additional liquidity to banks through the discount or refinancing windows. Refinancing is made on the request of the borrowing bank, and the central bank has little control over the demand for refinancing at a particular point of time. Refinancing has the effect of increasing the monetary base and bank reserves. However, in practice, central banks do change, albeit infrequently, the terms and rates of such refinance, to encourage or discourage banks from seeking refinance.

- Securitization. Securitization of assets has the same effect as refinancing on the monetary base and reserves. Though central banks have the power to fine tune the terms of securitization in the long run, the additional liquidity in the system arising out of securitization of assets does affect the money supply in the short term.

- Foreign exchange transactions. Central banks, sometimes, buy and sell foreign exchange. From a bank in the same country, such purchase of foreign currency not only increases ‘definitive money’,8 but also has the effect of increasing the monetary base and the bank’s reserves.

- Central Bank ‘Float’. A cheque deposited with the collecting banker in clearing, gives rise to a provisional liability in the central bank’s books (provided the cheque is not dishonoured), which is matched by a provisional asset—items in the process of collection—which the central bank would get from the paying bank when the cheque is cleared. During this period, the collecting bank’s reserves increase (the paying banker has not lost its deposit yet), and so does the reserves of the banking system by a corresponding amount. When the cheque is finally paid, the reserves of the banking system return to their original level. Since funds are constantly flowing through the clearing system, it is to be expected that the amount of items in process of collection will always exceed the amount of deferred credit items. The difference between the two amounts or the amount by which collection items exceed the deferred credit items is called the central bank’s ‘float’. This float is an additional source of reserves to the banking system, and since it is subject to daily fluctuations, the central bank may not have direct control over it.

- Defensive open-market operations. When the monetary base or reserves change as a result of any of the above factors, the central banks typically conduct OMOs to offset this effect. For instance, if the government were to spend ₹100 crore out of its funds, there is bound to be monetary expansion. However, the central bank can absorb the additional liquidity by an open market sale of the same amount. This is called a ‘defensive open-market operation’. In contrast, the central bank can conduct OMOs to effect a change in the monetary base or reserves. This is known as a ‘dynamic open-market operation’.

SECTION II

APPLICATION Of THE MONETARy POLICy TOOLS IN INDIA

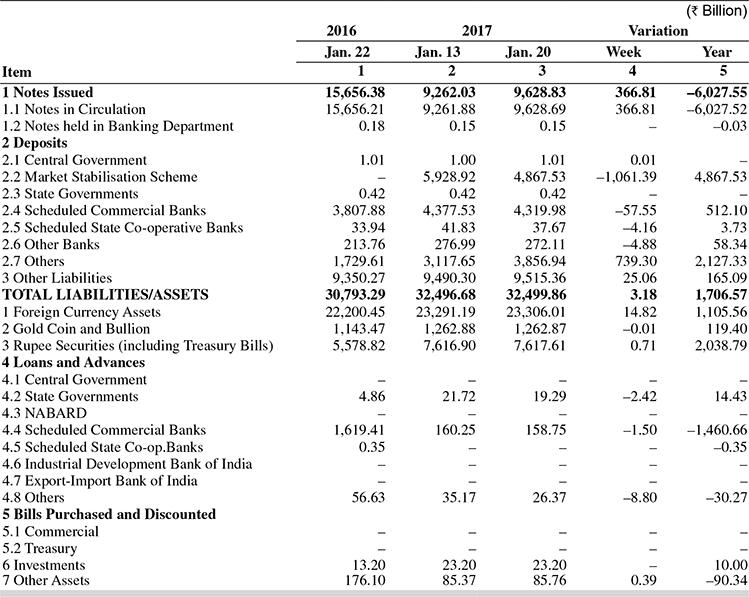

The Monetary Base in India

A summary of the Reserve Bank of India’s assets and liabilities as on January 2017 is shown in Table 2.2. It can be seen that the balance sheet structure is largely similar to the typical central bank’s balance sheet shown in Section I. The aggregate liabilities of the RBI will give an idea of the monetary base of the country. The detailed annual report of the RBI can be accessed at www.rbi.org.in

TABLE 2.2 RESERVE BANK OF INDIA—A SUMMARY OF LIABILITIES AND ASSETS

Measuring Money Supply in India9

In India, in accordance with the recommendations of the RBI’s Working Group on Money Supply (June 1998), the definition of money supply (termed ‘new monetary aggregates’) had been altered to adhere to the ‘residency concept’, in line with the best of international practices. The residency basis of compilation of monetary aggregates implies that non-resident deposit flows would not be included in money supply, i.e., capital flows in the form of non-resident repatriable foreign currency fixed liabilities with the Indian banking system, such as the balances under the Foreign Currency Non-resident Repatriable (Banks) Scheme [FCNR(B)] and Resurgent India Bonds (RIB) would not be included in money supply computation.

Four measures of money supply termed ‘new monetary aggregates’, are being compiled in India on the basis of the banking sector’s balance sheet, in conformity with the norms of progressive liquidity: M0 (the monetary base), M1 (narrow money), M2 and M3 (broad money).

M0 constitutes ‘reserve money’ maintained by banks with the central banks under the fractional reserve banking system. In specific terms, M0 is measured as follows:

M0 = currency in circulation + bankers’ deposits with the RBI + ‘other’ deposits with the RBI.

The concept of ‘narrow money’ is similar to that adopted by other countries, and is represented as follows:

M1 = currency with the public + demand deposits with the banking system + ‘other’ deposits with the RBI. restated,

M1 = currency with the public + current deposits with the banking system + demand liabilities portion of savings deposits with the banking system + ‘other’ deposits with RBI.

The components of M2 and M3 are as follows:

M2 = M1 + time liabilities portion of savings deposits with the banking system + CDs issued by banks + term deposits [excluding FCNR(B) deposits] with a contractual maturity of up to and including 1 year with the banking system.

restated,

M2 = currency with the public + current deposits with the banking system + savings deposits with the banking system + CDs issued by banks + term deposits [excluding FCNR(B) deposits] with a contractual maturity of up to and including 1 year with the banking system.

and,

M3 = M2 + term deposits [excluding FCNR (B) deposits] with a contractual maturity of over 1 year with the banking system + call borrowings from non depository financial corporations by the banking system.

The following points need to be noted:

- Currency with the public includes notes and coins of all denominations in circulation, but excludes cash in hand with banks.

- Demand deposits with the banking system implies demand deposits with commercial and co-operative banks, but excludes interbank deposits.

- ‘Other deposits’ with the RBI include current deposits of foreign central banks, financial institutions and quasi-financial institutions operating in India, and others such as the IMF and the IBRD.

Box 2.4 elaborates upon the differences between the new and old series of money supply in India.

BOX 2.4 DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE NEW AND OLD SERIES OF MONEY SUPPLY

The new series of broad money (NM3) differs from the old series (M3) by a magnitude comprising FCNR(B) deposits and RIBs, and banks’ pension and provident funds. Compilation of monetary aggregates on residency basis is in line with the best of international practices. Repatriable foreign currency fixed non-resident deposits (FCNR(B) deposits and RIBs in the Indian context) are excluded from money supply computation because they are BOP-related and do not constitute part of domestic demand for money.

This does not imply that RIBs and FCNR(B) deposits with the banking system in India do not affect money supply. If a bank sells foreign currency to the RBI, net foreign currency assets of the RBI increase, with a corresponding rise in the rupee value of reserve money. Since an increase in reserve money raises money supply in subsequent rounds of credit creation, FCNR(B) deposits and RIBs influence money supply.

If the RBI sterilizes the additional liquidity created by purchase of foreign currency from the banks by selling government securities from its portfolio, then this would not impact the reserve money and hence the money supply. The only effect is that FCNR(B) and RIBs would add to the net foreign currency assets of the RBI, with a corresponding reduction in government securities in the RBI balance sheet.

From the view of the country’s balance of payments (BOP), FCNR(B) deposits and RIBs constitute liabilities under the banking capital account and commercial borrowing account, respectively.

Pension and provident funds are essentially a portfolio of assets created to provide old age and retirement benefits. As they differ from deposits redeemable for cash at face value plus accrued interest, they need to be excluded from monetary aggregates in line with international practices.

Apart from the four new monetary aggregates, the Working Group has also proposed three ‘liquidity aggregates’ in conformity with the norm of progressivity in terms of liquidity, as follows:

L1 = M3 + all deposits with post office savings banks, excluding National Savings Certificates,

L2 = L1 + term deposits with term lending institutions and refinancing institutions (FIs) + term borrowings by FIs + CDs issued by FIs, and

L3 = L2 + public deposits of non-banking financial companies.

It is evident from the above discussion that not all money is equal, at least from the perspective of monetary authorities and the monetary policies. While money in transaction deposits like current or savings deposits gets spent fairly quickly, funds invested in term deposits or CDs remain with the banks for some time. Thus, the impact upon the economy and the banking system of creating ₹1 crore in current deposits and ₹1 crore in term deposits is quite different. However, central banks cannot control where the money goes in the financial system. Further, recent financial innovations, such as money market accounts or credit cards, which finance transactions in a big way, do not figure in the conventional definition of money.

Hence, most countries, including India, adopt broad money aggregates, such as M3 as the basis for arriving at policy measures. Table 2.3 shows the components and sources of money supply in India up to August 2016.

TABLE 2.3 COMPONENTS AND SOURCES OF MONEY SUPPLY

Operation of Reserve Requirements in India10

From the foregoing discussion, it is obvious that reserve requirements are mandatory if the liquidity in the banking system is to be preserved, and if even a single instance of default in repayment to depositors is to be avoided. All such reserves to be maintained as a legal requirement are termed ‘Primary Reserves’.

There are legal reserve requirements under Section 42(1) of the RBI Act, 1934, stipulating that banks maintain a CRR on their liabilities. In addition, banks are bound under Section 24 of the Banking Regulation (BR) Act, 1949, to maintain a portion of these liabilities in cash or near cash form, termed the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR).

As the nomenclature implies, the CRR is maintained as cash reserves, while the SLR is maintained in liquid, near cash instruments. While the aim of the CRR is to take care of immediate liquidity needs, there is a two-fold objective for the SLR: to provide profitability along with liquidity, since the funds would be parked in interest yielding government and other approved securities; and to augment the government’s borrowing program.

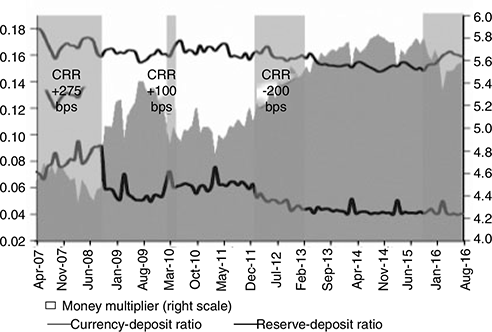

In the earlier simplified example of the Money Multiplier, it is seen that the fractional reserve requirement (the equivalent of CRR/SLR) is determined by the central bank as a percentage of deposits garnered by the bank. In reality, banks have varied sources of funds, as we will learn in a subsequent chapter. Hence, the CRR and SLR are prescribed as a minimum percentage of ‘net demand and time liabilities’ (NDTL) of each bank. Since the actual maintenance of the reserves is based on the NDTL, it is necessary to understand the constituents of NDTL and the method of calculating the actual reserves. Figure 2.2 shows the trend in growth in money supply, reserve money (see Box 2.5).

FIGURE 2.2 MONEY SUPPLY , RESERVE MONEY GROWTH AND THE MONEY MULTIPLIER IN INDIA

BOX 2.5 THE DEBATE OVER RELEVANCE OF CRR

Should CRR continue as an instrument of Monetary Policy in India? This debate was sparked off once again in September 2012.

Those who argue that CRR should go have expressed the following views:

- It curbs banks’ ability to lend.

- Funds blocked in CRR yield no return.

- Banks face a disadvantage compared with mutual funds, non-banking finance companies (NBFCs), and insurance companies, which are not subject to CRR.

- The Narasimham Committee-1 mandated a sharp reduction in the CRR and SLR.

- The argument was reiterated by the Raghuram Rajan committee report on financial sector reforms in 2009.

However, those in support of CRR feel that the tool helps monetary policy achieve some important objectives:

- It fulfills an important regulatory function in countries like India where the Open Market Operations (OMO) face some structural rigidities.

- The CRR can be an effective short-term tool to check inflation by varying money supply.

- Banks should view the zero interest on CRR balances as a fee paid to the RBI for its supervisory function.

- Banks alone can mobilize low-cost savings and current account deposits. Mutual funds, NBFCs, and insurance companies do not have access to such funds. So, banks have to ensure liquidity at all times and CRR is an effective tool to ensure liquidity.

Experts also feel that such pertinent questions should be raised in respect of the SLR and government bond holdings of banks, that do not yield high returns.

Net Demand and Time Liabilities

Bank liabilities can be broadly classified into external and internal liabilities. While equity, reserves and provisions are the internal liabilities, external liabilities are those that the bank owes to outsiders. External liabilities can be further classified into ‘liabilities to the banking system’ and ‘liabilities to others’.

NDTL is broadly those liabilities of banks in India, which have been sourced from the ‘banking system’ and ‘others’. It is to be noted that liabilities of overseas branches will be excluded since these branches operate under the jurisdiction of the countries in which they are located. Therefore, to grasp the concept and computation of NDTL, it is necessary to know what constitutes the banking system, assets with the banking system, demand and time liabilities to be reckoned for NDTL and how the reserves are calculated and maintained by banks.

Annexure I answers the following questions:

- What constitutes the banking system in India?

- Which type of institutions are excluded from the banking system?

- What are ‘assets with the banking system’?

- What are the demand liabilities to be considered while computing the NDTL?

- What are the time liabilities to be considered while computing the NDTL?

- What are the ‘other demand and time liabilities (ODTL)’ to be considered while computing the NDTL?

- What are the liabilities to be excluded while computing the NDTL?

- What are the categories of liabilities exempted for calculation of reserve requirements under the CRR and SLR?

- How are the reserves calculated and maintained by banks?

In case of doubt or dispute in classification of liabilities, the RBI has the power to decide on the classification under section 18(2) of the BR Act.

Operation of the Bank Rate in India

The Section 49 of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 requires the Reserve Bank to make public (from time-totime) the standard rate at which it is prepared to buy or re-discount bills of exchange or other commercial papers eligible for purchase under that Act. Since, discounting/re-discounting by the Reserve Bank remained in disuse, the Bank Rate has not been active. Moreover, even for the conduct of monetary policy, instead of changing the Bank Rate, monetary policy signalling was done through modulations in the reverse repo rate and the repo rate under the Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF) (till May 3, 2011) and the policy repo rate under the revised operating procedure of monetary policy (from May 3, 2011 onwards). As a result, the Bank Rate had remained unchanged at 6 per cent since April 2003. Effective from February 13, 2012, the Bank Rate has been aligned with the Marginal Standing Facility (MSF) rate. (See also Box 2.6 “Changes in operating procedure of Monetary Policy”, below). The MSF, standing at 100 bps above the policy repo rate, is now regarded as serving the purpose of the Bank rate.

Being the ‘discount rate’ ( see also the earlier discussion on ‘discount rate’ or ‘bank rate’ under the sub heading ‘Central Bank tools to regulate Money supply’), or the rate at which the central bank lends to commercial banks, the bank rate should essentially be higher than the policy repo rate. Thus, the bank rate was aligned to the MSF, which was pegged at 100 bps over the repo rate. The RBI has clarified that this is ‘a one time adjustment not to be construed as a monetary policy action’. The alignment with the MSF also implies that all rates specifically linked to the bank rate, such as penal interest levied on shortfall in reserves kept by commercial banks with the RBI, will now be linked to the MSF and revised accordingly.

BOX 2.6 CHANGES IN THE OPERATING PROCEDURE OF MONETARY POLICY

Since initiation of financial sector reforms in the early 1990s, and the development of the money market, the operating procedure of the Monetary Policy in India has undergone significant changes. In 2000, the LAF emerged as the principal operating procedure of the Monetary Policy, with the repo and reverse repo rates as the key instruments for signalling the stance of the Policy. The LAF had been supported by other instruments such as the CRR, OMO, and the MSS.

However, the aftermath of the financial crisis brought in large volatility in capital flows and fluctuations in government’s cash balances. These developments impacted liquidity management by the RBI.

In 2010, the RBI decided to review the operating procedure of the Monetary Policy, and constituted a Working Group (Chairman: Shri Deepak Mohanty).

Based on the Group’s recommendations, the Monetary Policy statement for 2011–12 effected the following changes in the operating procedures:

- The weighted average overnight call money rate would be the operating target of the Monetary Policy.

- The repo rate will be the one independently varying policy rate.

- Under the MSF, commercial banks can borrow overnight upto 1% of their NDTL (now, revised to 2% of NDTL).

Open Market Operations in India

In order to tackle uncertainty in financial markets, the RBI, in the late 1990s, decided to accept private placement of government securities with the purpose of off loading them into the market through active OMOs. This measure effectively met the large borrowing requirements of the government, without putting pressure on interest rates and paved the way for RBI to use the bank rate, repo rate and the reserve requirements in conjunction with the OMOs for meeting short-term monetary policy objectives.

The Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF), introduced in 2000, operates through repos and reverse repos to set the corridor for money market interest rates. Both repo and reverse repo rates are fixed by the RBI, with the spread between the two rates determined by the central bank based on market conditions and other relevant factors.

The LAF has settled into predominantly a fixed rate overnight auction, though repo auctions can be conducted at variable or fixed rates for overnight or longer terms. The second LAF introduced in November 2005 enables market participants fine tune liquidity management. LAF operations are supplemented by RBI’s standing facilities linked to the repo rate, in the form of export credit refinance to banks and standing liquidity facility to Primary Dealers.

The move towards indirect instruments of monetary control (the CRR, e.g., is a direct instrument of monetary control) has provided greater flexibility to the regulator, not only in fixing and adjusting policy rates, but also in monitoring them on a daily basis.

In addition, the central bank also aims at developing a repo market outside the LAF for both bank and non-bank participants, serving multiple purposes providing a stable collateralized funding alternative, promoting smooth transition of the call/notice money market into a pure interbank market and adding depth to the underlying government securities market.11

Repo Market Instruments Outside the LAF

- Collateralized borrowing and lending obligations: Under the collateralized borrowing and lending obligations (CBLO), participants can lend and borrow funds, against the security of government securities, including treasury bills, for maturity periods ranging from 1–90 days (with flexibility up to 1 year). Transactions can be carried out in this market by banks, financial institutions, insurance companies, mutual funds, PDs, non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), non-government pension funds and corporate participants. Clearing Corporation of India Limited (CCIL), which developed and introduced the instruments in 2003, provides the electronic dealing platform for transactions, through the Indian financial network (INFINEN), a closed user group for members of the negotiated dealing system who maintain current accounts with the RBI, and through the Internet for other participants. Borrowing limits for each borrower is fixed by CCIL at the beginning of every day, based on the securities deposited by the borrower, and after applying appropriate hair cuts on the marked to market securities. CCIL guarantees settlement of transactions in CBLO. The operations in CBLO do not attract cash reserve requirements and unencumbered securities can be included as part of SLR requirements.

- Market repo: From 2003, non-banking financial companies, insurance companies, housing finance companies and mutual funds could access the repo markets, and later on, non-scheduled urban co-operative banks and listed companies with gilt accounts with scheduled commercial banks were also permitted to transact in this market. Their participation serves to broaden the government securities market (market repos are currently restricted to the government securities market). Controls to ensure transparency in transactions and delivery versus payment) have been built into the system.

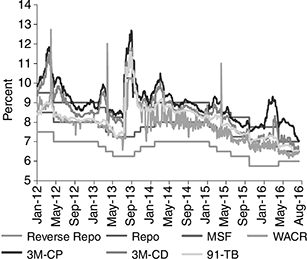

Both the CBLO and market repos have helped in aligning short-term money market rates to the repo and reverse repo rates in the LAF, as Figure 2.3 shows. It is also to be noted that repo markets outside the LAF have banks, PDs and corporates as major borrowers of funds supplied typically by mutual funds and insurance companies.

It can be seen from Figure 2.3 that the corridor has a fixed width with the repo rate in the middle of the corridor. The width of the corridor can be changed by the RBI. It is also evident, that CP and CD rates rule higher when liquidity conditions are tight, and tend towards the MSF rate (equivalent to the Bank rate) when liquidity conditions improve. A similar trend is seen in call money rates within the corridor of MSF-repo-reverse repo rate (reverse repo rate is set at fixed bps lower than the repo rate by the RBI).

Repos of various forms are important financial instruments in the "Money Markets", which are a key feature of all financial markets. Annexure II provides an introduction to India's Money markets.

The Market Stabilization Scheme (MSS-2004) It has been designed to lend more flexibility to liquidity management. Increasing capital inflows into India has necessitated managing their impact on liquidity. However, since external capital flows could be volatile, the central bank would have to make choices for day to day exchange rate and monetary management. When the central bank intervenes in the foreign exchange market through purchase of foreign exchange, it injects liquidity into the system through corresponding sale of domestic currency. Similarly, when the central bank sells foreign exchange, liquidity is absorbed from the system. It is possible that such operations cause unanticipated expansion or contraction of money supply, which may not necessarily be consistent with the prevailing monetary policy stance. The central bank, therefore, looks at neutralizing such impact on money supply, partly or wholly. This process is termed ‘sterilization’. OMO operations are commonly used as instruments of sterilization. However, while the liquidity impact of capital inflows have been managed using the LAF and the OMO, the process ended up depleting the stock of government securities held by the RBI. In response to this situation, the MSS was launched in agreement with the Government of India. Under this scheme, the government would issue treasury bills or dated securities in addition to the normal borrowing requirements, with the purpose of absorbing liquidity from the system. The MSS securities would be treated and serviced like other marketable government securities, but would be maintained and operated in separate accounts by the RBI. The amount held in this account would be appropriated only for the redemption or buy back of securities under MSS. Generally, short-term instruments are preferred for MSS operations to provide flexibility in liquidity management. The ceiling for outstanding balance under the MSS for the fiscal year 2012–13 has been fixed at ₹50,000 crore by the RBI. Thus, there has been no change in the ceiling amount over the last fiscal year.

FIGURE 2.3 MOVEMENT IN MONEY MARKET RATES

WACR denotes the Weighted Average Call Rate; 3M-CP denotes 3 month Commercial Paper discount rate; 3M-CD denotes 3 month Certificate of Deposit rate; 91=TB denotes 91 day Treasury Bill rate

Conduct of Monetary Policy in India - Monetary Policy Committee (MPC)12

Amendments to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, which came into force on June 27, 2016 has empowered the conduct of monetary policy in India. For the first time in its history, the RBI has been explicitly provided the legislative mandate to operate the monetary policy framework of the country.

The primary objective of monetary policy has also been defined explicitly for the first time – “to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth.”

The amendments also provide for the constitution of a monetary policy committee (MPC) that would determine the policy rate required to achieve the inflation target, another landmark in India’s monetary history. The composition of the MPC, terms of appointment, information flows and other procedural requirements such as implementation of and publication of its decisions, and consequences of failure to maintain the inflation target as well as remedial actions have been specified.

On August 5, 2016 the Government set out the inflation target as four per cent with upper and lower tolerance levels of six per cent and two per cent, respectively.

The Government and the RBI have constituted the six member MPC. The MPC took its first decision on October 4 under the Reserve Bank’s fourth bi-monthly monetary policy review for 2016-17.

The MPC consists of the Governor of the Reserve Bank, the Deputy Governor-in-charge of monetary policy, one officer of the Bank to be nominated by the Central Board of the Reserve Bank and three members to be appointed by the Central Government. Each member shall have one vote, and in the event of a tie, the Governor can exercise a casting or second vote.

The amended RBI Act establishes the procedures for MPC meetings. It specifically lays down that at least four meetings of the MPC shall be organized in a year (Section 45ZI).

The Government of India and the RBI have signed a Monetary Policy Framework Agreement (MPFA) to adopt the objective of price stability with growth.

The cross-country experience in this regard is varied, both in terms of the number of meetings and the press conferences that usually follow the meetings in order to explain the stance of monetary policy for the benefit of the public. A survey of country practices suggests a central tendency among major central banks to hold four press conferences a year, although the number of MPC meetings may be higher.

BOX 2.5 EFFECTS OF DEMONETIZATION ON KEY VARIABLES IN THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM

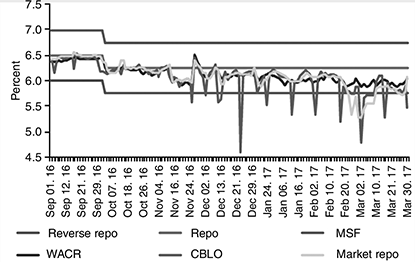

The following pictorial depictions show the contrasting movements in key financial system variables pre and post demonetization.

Contrast Figure 2.4 with the trend observed in Figure 2.3.

FIGURE 2.4 POLICY CORRIDOR AND MONEY MARKET RATES

It can be seen that demonetization induced surplus liquidity conditions had a bearing on volumes and rates. Call rates were depressed (as evidenced by WACR) as banks were flush with funds.

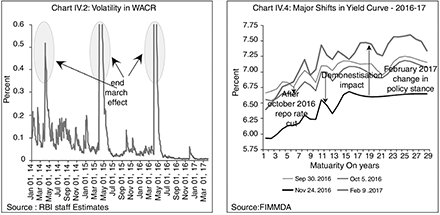

Figures 2.5 and 2.6 below show graphically how the rates and yield curves were impacted.

FIGURES 2.5 AND 2.6 VOLATILITY IN WACR AND MAJOR SHIFTS IN YIELD CURVE DURING 2016-17

Surplus liquidity conditions also saw a fall in Certificate of Deposit (CD) issues. Commercial Paper (CP) rates also declined significantly.

SECTION III

MONETARY POLICY TOOLS IN SELECT COUNTRIES

The United States of America13

Monetary Policy Tool 1—Reserve Requirements Reserve requirements are the portion of deposits that banks may not lend and have to keep either on hand or on deposit at a Federal Reserve Bank. Within limits specified by law, the Board of Governors has sole authority over changes in reserve requirements. All depository institutions including commercial banks, savings banks, savings and loan associations, credit unions, US branches and agencies of foreign banks, etc. are required to maintain reserves of 3–10 per cent on transaction deposits. Table 2.4 shows the reserve requirement stipulated by the Fed.

TABLE 2.4 RESERVE REQUIREMENTS

Net Transaction Accounts

Total transaction accounts consists of demand deposits, automatic transfer service (ATS)accounts, NOW accounts, share draft accounts, telephone or preauthorized transfer accounts, ineligible bankers acceptances, and obligations issued by affiliates maturing in seven days or less. Net transaction accounts arc total transaction accounts less amounts due from other depository institutions and less cash items in the process of collection.

Banking institutions can do weekly or quarterly reporting based on certain mandatory filings with the Fed. On an average, the maintenance period of reserves is 14 days. Details of maintenance requirements can be accessed at : https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/reserve-maintenance-manual.pdf.

The Federal Reserve Banks are authorized to pay interest on balances maintained to satisfy reserve balance requirements and on excess balances.

The interest rate for balances maintained to satisfy reserve balance requirements (IORR rate) is determined by the Board of Governors. The interest rate for excess balances (IOER rate) is also determined by the Board of Governors and gives the Federal Reserve an additional tool for the conduct of monetary policy. The interest rates for balances maintained to satisfy reserve balance requirements and excess balances are available on the Federal Reserve Board website.

Monetary Policy Tool 2—The Discount Rate The Federal Reserve Banks offer three discount window programs to depository institutions: primary credit, secondary credit and seasonal credit, each with its own interest rate. All discount window loans are fully secured.

Under the primary credit program, loans are extended for a very short term (usually overnight) to depository institutions in generally sound financial condition. Depository institutions that are not eligible for primary credit may apply for secondary credit to meet short-term liquidity needs or to resolve severe financial difficulties. Seasonal credit is extended to relatively small depository institutions that have recurring intra-year fluctuations in funding needs, such as banks in agricultural or seasonal resort communities.

The discount rate charged for primary credit (the primary credit rate) is set above the usual level of shortterm market interest rates. (Because primary credit is the Federal Reserve’s main discount window program, the Federal Reserve at times uses the term ‘discount rate’ to mean the primary credit rate.) The discount rate on secondary credit is above the rate on primary credit. The discount rate for seasonal credit is an average of selected market rates. Discount rates are established by each Reserve Bank’s board of directors, subject to the review and determination of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The discount rates for the three lending programs are, in most cases, the same across all Reserve Banks.

The current rates (beginning February 19, 2010) are 0.75 per cent for primary credit, 1.25 per cent for secondary credit, and 0.20 per cent for seasonal credit.

The current primary credit rate was increased from 1 percent to 1-1/4 percent, effective from December 15, 2016, and the secondary credit rate was set 50 basis points above the primary credit rate, while the seasonal credit rate would continue to be reset every two weeks as the average of the daily effective federal funds rate and the rate on three-month CDs over the previous 14 days, rounded to the nearest 5 basis points.14

Monetary Policy Tool 3—Open Market Operations Open market operations (OMOs)—the purchase and sale of securities in the open market by a central bank—are a key tool used by the Federal Reserve in the implementation of monetary policy. The short-term objective for open market operations is specified by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Before the global financial crisis, the Federal Reserve used OMOs to adjust the supply of reserve balances so as to keep the federal funds rate—the interest rate at which depository institutions lend reserve balances to other depository institutions overnight—around the target established by the FOMC.

The Federal Reserve's approach to the implementation of monetary policy has evolved considerably since the financial crisis, and particularly so since late 2008 when the FOMC established a near-zero target range for the federal funds rate. From the end of 2008 through October 2014, the Federal Reserve greatly expanded its holding of longer-term securities through open market purchases with the goal of putting downward pressure on longterm interest rates and thus supporting economic activity and job creation by making financial conditions more accommodative.

During the policy normalization process that commenced in December 2015, the Federal Reserve will use overnight reverse repurchase agreements (ON RRPs)—a type of OMO—as a supplementary policy tool, as necessary, to help control the federal funds rate and keep it in the target range set by the FOMC.15

The Eurosystem16

The eurosystem comprises the European Central Bank (ECB) and the national central banks (NCBs) of the European Union (EU) countries that have adopted the euro (The euro area). Since 1 January 1999, the ECB has been responsible for conducting monetary policy for the euro area that at present comprises of 18 member countries. A statute established both the ECB and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB). The ESCB comprises the ECB and the NCBs of all EU member states whether they have adopted the euro or not. The ECB is the core of the eurosystem and the ESCB. The eurosystem and the ESCB will co-exist as long as there are EU member states outside the euro area.

Monetary policy tools used to achieve this objective through steering short-term interest rates are as follows: (1) minimum reserve requirements; (2) open market operations; and (3) standing facilities. By influencing the amount of liquidity available in the eurosystem, the level of short-term rates in the money market is regulated.

Monetary Policy Tool 1—Minimum Reserve Requirements All credit institutions17 in the system are required to hold minimum reserves in separate accounts with the NCBs over a specified maintenance period (around a month). The Eurosystem pays a short-term interest rate on these accounts. The reserve requirement of each institution is determined in relation to elements of its balance sheet. Compliance with the reserve requirement is determined on the basis of the institutions’ average daily reserve holdings over a maintenance period of about one month. The reserve maintenance periods start on the settlement day of the Main Refinancing Operation (MRO). The required reserve holdings are remunerated at a level corresponding to the average interest rate over the maintenance period of the MROs of the eurosystem.

The minimum reserve requirements take three forms—Reserve coefficients, Standardized deduction, and Lump-Sum allowance.

Reserve Coefficients

Standardized Deductions

| As from the maintenance period starting on | Debt securities issued with maturity upto 2 years | Money market paper |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Jan. 1999 | 10% | 10% |

| 24th Jan. 2000 | 30% | 30% |

| 14th Dec. 2016 | 15% | 15% |

Lump-Sum Allowance

| As from the maintenance period starting on | |

|---|---|

| 1st Jan. 1999 | €1,000,00 |

Monetary Policy Tool 2—Open Market Operations OMOs, coordinated by the ECB, but carried out by NCBs, take four distinct forms: Open market operations play an important role in steering interest rates, managing the liquidity situation in the market and signalling the monetary policy stance. Five types of instruments are used. The most important instrument is reverse transactions, which are applicable on the basis of repurchase agreements or collateralized loans. The other instruments used are outright transactions, issuance of debt certificates, foreign exchange swaps and collection of fixed-term deposits.

- Main refinancing operations (MROs) to provide liquidity, with a frequency and maturity of 1 week.

- Longer term refinancing operations (LTROs) to provide liquidity, however with a longer frequency of a month and maturity of 3 months. Through MROs and LTROs, the Eurosystem lends funds to banks for short periods, secured by collateral. Longer-term refinancing operations that are conducted at irregular intervals or with other maturities, e.g., the length of one maintenance period, 6 months, 12 months or 36 months are also possible. These operations aim to provide counter parties with additional longer-term refinancing.

- Fine tuning operations (FTOs) as and when warranted to smooth the effects of unexpected liquidity imbalances on interest rates, and

- Structural operations through reverse transactions, outright transactions and issuing debt certificates.

Monetary Policy Tool 3—Standing Facilities The two standing facilities—a marginal lending facility and a deposit facility—offered by the Eurosystem set boundaries for overnight market rates by providing and absorbing liquidity. As their names imply, the marginal lending facility allows credit institutions to obtain overnight liquidity from the NCBs against the security of eligible assets, while the deposit facility enables credit institutions to make overnight deposits with the NCBs. These two facilities form a corridor—the lending facility forming the ceiling rate for the corridor and the deposit facility forming the floor rate—around the minimum bid rate and, therefore, set limits on the fluctuations in the short-term money market rates.

Other Developed and Developing Countries

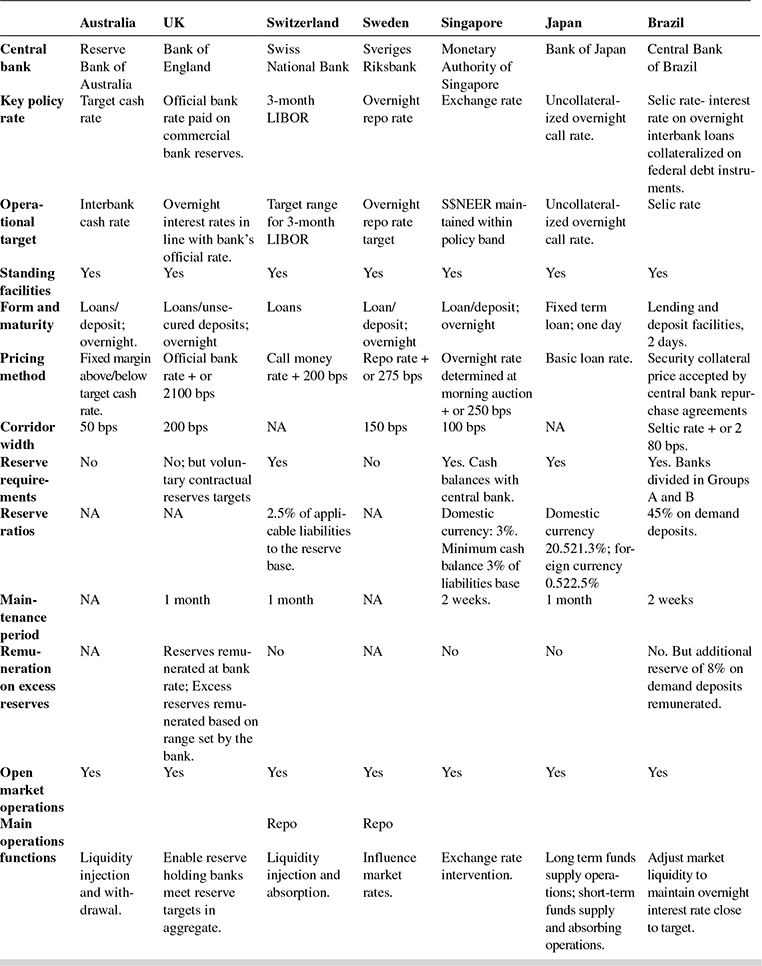

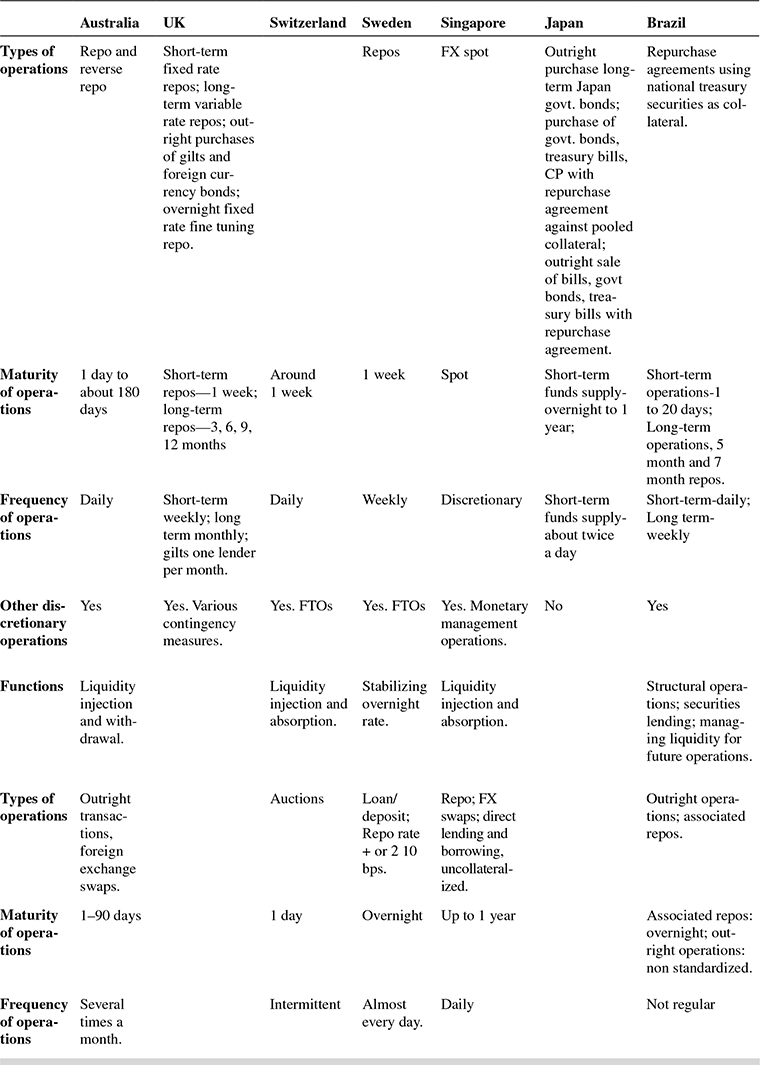

Table 2.5 summarizes the key aspects of monetary tools in operation in select developed and developing countries.

TABLE 2.5 KEY ASPECTS OF MONETARY TOOLS IN OPERATION IN SELECT DEVELOPED AND DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- The ability of banks to create money is constrained by the reserves they would have to maintain. The central banks can control the creation of money and thus the money supply, by controlling the reserve requirements from the banking system.

- In an economy in which all payments are made through the banking system, by cheques, the total quantity of money (deposits/credit) is the inverse of the reserve ratio times the monetary base (definitive money).

- The total liabilities of the central bank constitute the ‘monetary base’.

- There are three broad measures economists use when looking at the money supply: M1, a narrow measure of money’s function as a medium of exchange; M2, a broader measure that also reflects money’s function as a store of value; i.e., and M3, a still broader measure that covers items regarded as close substitutes of money. The indicators that measure money supply, though conceptually similar, differ in nomenclature and composition from country to country.

- Most central banks use three primary tools to influence money supply in the economy—the reserve requirements, the bank rate or discount rate and OMOs. However, when OMOs are used as a primary policy instrument, the use of other instruments, such as discount (bank) rate and the CRR becomes more selective and restricted.

- Reserve requirements in the nature of CRR are considered ‘basic’ compared with the level of sophistication that OMOs demand of the market. Central bank in several developed countries impose minimal or no reserve requirements on their banks. However, reserve requirements are still used in many instances as a way of enhancing the efficacy of OMOs and regulating money supply in the short term.

- The widespread use of OMOs has given rise to active ‘repo’ markets in many countries. The attractiveness of repos stems from the fact that the features of repo contracts are well suited to influence the interest rates in the economy, through impacting two of the main channels of monetary policy—controlling liquidity in money markets and signalling to markets the desired interest rate levels.

- The central bank can change the monetary base deliberately through any of the tools described above. However, monetary base can also change due to other factors as well, without any intervention by the central bank, such as refinance or discount windows, securitization, foreign exchange transactions, central bank ‘float’, defensive OMOs, to name a few.

- In India, the definition of money supply adheres to the ‘residency concept’, in line with best international practices. The residency basis of compilation of monetary aggregates implies that non-resident deposit flows would not be included in money supply, i.e., capital flows in the form of non-resident repatriable foreign currency fixed liabilities with the Indian banking system.

- All financial institutions in India, which are into lending and investment operations are required to maintain a specified amount of reserves as cash/bank balances with the central bank and as investment in approved securities. All such reserves that are to be maintained as a legal requirement are termed ‘primary reserves’. In the Indian context, these reserve requirements are categorized as the CRR and SLR. The CRR and the SLR are prescribed as a minimum percentage of ‘net demand and time liabilities’ (NDTL) of each bank operating in India.

- The LAF, introduced in 2000, operates through repos and reverse repos to set the corridor for money market interest rates. Both repo and reverse repo rates are fixed by the RBI, with the spread between the two rates determined by the central bank based on market conditions and other relevant factors.

- Repo market instruments also exist outside the LAF, such as CBLO, Market Repo and the MSS.

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

- Rapid fire questions

Answer ‘True’ or ‘False”

- RBI regulates banks and financial institutions in India.

- RBi regulates the securities markets and insurance sector in India.

- RBI has the responsibility of maintaining financial stability in the country.

- CRR is higher than SLR.

- Low call rates indicate tightness of liquidity in the financial system.

- Mutual funds are money market instruments.

- In a REPO both cash and security get simultaneously exchanged.

- Commercial Paper has to be rated by a Credit rating agency before being issued in the market.

- Certificates of deposit are money market instruments.

- The Bank rate and the MSF are conceptually the same in India.

Check your score in Rapid fire questions

- True

- False

- True

- False

- False

- False

- True

- True

- True

- True

- Fill in the blanks with appropriate words and expressions

- The two important Acts regulating the Indian Banking system are the ————— Act, 1934, and the ————— Act, 1949

- The three important Monetary Policy tools for central banks are —————, ————— and —————

- In India, the most significant monetary policy tool is —————

- The RBI conducts a formal Monetary Policy review every ————— months

- The banking system regulator in the USA is the —————

- The banking system regulator in the Eurozone is —————

- When RBI purchases government securities under the LAF, it is ————— liquidity in/ from the banking system

- When the Central Bank reduces the reserve requirements of banks, it is ————— liquidity into / from the banking system

- The most important signaling rate for the Indian banking system is the ————— rate

- The RBI acts as ————— to the Government and to banks

- Expand the following abbreviations in the context of the Indian financial system

- SLR

- CRR

- OMO

- SEBI

- IRDA

- PFRDA

- MPC

- LOLR

- MSF

- LAF

- Test your concepts and application

- Define the various money supply measures. What is the rationale for these different measures of money supply?

- What are the goals of monetary policy in India? How well have they been achieved in recent times? If the goals have not been achieved satisfactorily, what are the reasons?

- What is the difference between an outright open market transaction and a Repo? Why are OMOs being increasingly used as the primary monetary policy tool?

- The NDTL of a bank operating in India on the reporting Friday dated 12 August 2009, is computed as ₹20,000 crore.

- When does the maintenance period for the CRR and the SLR begin?

- The CRR is to be maintained at 5 per cent, and the minimum CRR to be maintained on a daily basis is at 70 per cent. The bank expects that its internal surplus funds will amount to ₹500 crore during the first 6 days of the maintenance period, ₹600 crore during the next 5 days of the maintenance period and ₹500 crore for the remaining days of the maintenance period. What is the amount of funds the bank should mobilize to maintain the CRR without attracting penalty?

- If short-term interest rates are expected to rule at 4 per cent for the first 7 days of the maintenance period, 4.5 per cent during the next 3 days of the maintenance period and at 6 per cent thereafter, and the bank decides to borrow, what would be the interest outgo?

- If the penal provisions are as described in the annexure to this chapter, would the bank decide to pay the penalty or borrow to meet the CRR requirements?

- A bank’s liabilities comprises deposits amounting to ₹2,000 crore and an equity of ₹200 crore. On this liability base, the bank has to maintain a CRR of 5 per cent and an SLR of 25 per cent. If the bank can earn an average yield of 15 per cent on its loanable funds and its fixed expenses, including manpower expenses, amount to about 7 per cent of its deposits, what should be the average rate of interest the bank can pay on its deposits, if it wants to earn a profit of ₹20 crore for a period of 1 year? Assume that income on investments, along with interest earned on CRR and SLR investments, amounts to 22 per cent of the total income. Also assume that the balance sheet data given above are all averages applicable for the entire period.

- A bank has an equity base of ₹700 crore. If the CRR is to be maintained at 5 per cent and the SLR at 25 per cent, what is the number of branches the bank can sustain given the following expectations?

- Average cash and bank balance per branch ₹1 crore.

- Average fixed cost per branch ₹3 crore.

- Average deposits per branch ₹100 crore.

- Capital to assets ratio of 10.

Also, compute the level of fund-based business the bank can achieve.

- What is the difference between a repo and reverse repo transaction?

- A bank enters into a repo agreement in which it agrees to buy approved securities from an authorized dealer at a price of ₹1,49,25,000, with an agreement to pay back at a price of ₹1,50,00,000. What is the yield on the repo if it has (a) a 5 day maturity and (b) a 15 day maturity?

- What is likely to happen to: (a) deposits with the banking system; and (b) interest rates in each of the following transactions?

The central bank decreases CRR by 1 percentage point.

The central bank increases CRR by 1.5 percentage points.

The central bank sells government securities of ₹5 crore to the banking system.

The central bank buys government securities of ₹10 crore from the banking system.

- Assume that the RBI injects ₹60,000 crore liquidity into the banking system and that the current CRR is at 7 per cent. If there are no other leakages of funds from the banking system, how much of new deposits can the banking system create? If subsequently, the RBI withdraws ₹40,000 crore liquidity from the same banking system. What will be the current level of deposits with the banking system?

TOPICS FOR FURTHER DISCUSSION

- Study the monetary policies of the RBI of the last few years.

- What has been the stance of the RBI in respect of CRR and SLR requirements?

- Do you find any significant policy shifts in the usage of the three tools of monetary policy—reserve requirements, bank rate and OMOs?

- If such shifts have taken place, why have they been necessitated?

- What has been the impact of such shifts on banks?

- Go to the RBI website www.rbi.org.in and study the latest money market and LAF operations. What inferences can you draw from the transactions about what RBI is trying to achieve on the liquidity front?

- Study the way monetary policies are formulated and the stance of these policies in various countries. What similarities/dissimilarities do you notice with the manner in which RBI conducts Monetary Policy?

ANNEXURE I

COMPUTATION OF THE NDTL FOR THE BANKING SYSTEM IN INDIA18

What Constitutes the Banking System in India?

The banking system (for the purpose of CRR/SLR maintenance) includes the State Bank of India and its subsidiaries, the nationalized banks, co-operative banks, all private sector banks, foreign banks operating in India and any financial institution notified by the central government, such as PDs.

The banking system excludes the Reserve Bank of India, EXIM bank, NABARD, SIDBI and other similar financial institutions and primary credit societies, co-operative land mortgage/development banks and foreign banks having no branches in India, as well as Regional Rural banks.

What Constitute the ‘Assets with the Banking Systems’?

‘Assets with the banking system’ include balances with the banking system in current accounts; balances with banks and notified financial institutions in other accounts; funds made available to the banking system by way of loans or deposits repayable at call or short notice of a fortnight or less and loans other than money at call and short notice made available to the banking system. Any other amounts due from banking system which cannot be classified under any of the above items are also to be taken as assets with the banking system.

What are the Demand and Time Liabilities to be Included for Computing NDTL?