CHAPTER FIVE

Uses of Bank Funds—The Lending Function

CHAPTER STRUCTURE

Section III Financial Appraisal for Credit Decisions

Section IV Fund Based, Non Fund Based and Asset Based Lending

Section V Loan Pricing and Customer Profitability Analysis

Annexures I, II, III, IV, V (Case study)

KEy TAKEAwAyS FROm THE CHAPTER

- Understand why banks lend.

- Learn how banks lend—Principles of lending.

- Understand the process of making a loan from start to finish.

- Learn the fundamentals of credit appraisal.

- Understand how loans are priced.

- Understand how banks choose profitable customers.

SECTION I

BASIC CONCEPTS

Introduction

Assume that you have ₹10 lakh with you and that a dear friend approaches you with a request to lend him ₹10 lakh for a business he wishes to start. You need the money for buying a house in a year’s time, and your friend agrees that he will return the money at the time you require it, out of the profits he generates from the business. A year goes by. You have negotiated the price of the house you want to buy, and ask your dear friend to repay the ₹10 lakh he took from you. You remind him of his assurance that he would repay you out of the profits from his business. Listed below are a few possible scenarios.

- Your friend repays the loan in full and thanks you profusely for your timely help.

- Your friend regrets that the business did not generate the expected profit, and he will be able to repay only ₹5 lakh immediately. He assures you that he would repay the remaining amount within another year if the business improves as expected.

- Your friend gives you the story of how the project did not take off, and therefore he would be unable to repay even a small part of the total amount borrowed.

In the first case, you are happy that you could help your friend in need and do not envisage the other two possible outcomes. However, what if any of the latter two events happened? You would have lost your savings as well as the dream house. You regret having trusted your friend and his judgment about the prospects of his business. You regret not having had asked for more information about the project and its likelihood of success. You regret not having called your friend periodically to find out how the business venture was progressing.

In short, you could probably have avoided the unpleasant situation of your friend having to renege on his promise to you if you had had more information on the project, its risks and prospects; written a formal contract, enforceable in a court of law; instituted safeguards by way of terms and conditions and monitored the project cash flows periodically.

Let us consider another scenario. You have now invested your hard-earned savings of ₹10 lakh in a bank. Your dear friend approaches the same bank and requests a loan of ₹10 lakh for his business venture. What does the bank do? It calls for ‘information’—about your friend, his antecedents, his previous track record in business and honouring commitments, the nature and scope of his new venture, the nature of the industry, the market, the technology, proposed suppliers and buyers and how much he is willing to invest in the business if the bank were to grant him his request. The bank compares the information he gives with that available with it in respect of similar business ventures, and determines the probability of success. The bank lends your friend the money if it is satisfied that the ₹10 lakh will be repaid on the contracted date. At the end of 1 year, with your dream house almost finalized, you go to the bank and ask for your money back. The bank repays you without demur and with interest for the period for which your money had been lent to the bank. At the end of the same year, your friend would have repaid the bank in full; or repaid only a part of the amount borrowed since the business did not yield the expected returns or repaid nothing, since the project had not taken off as expected. However, unlike in the first scenario, where you were likely to be put to partial or total loss, you have not been affected by your friend’s business success or failure.

Why is this so? The bank, as the financial intermediary, has assumed the risks you would have faced had you lent to your friend directly. Not only that, the risks in lending to your friend has not deterred the bank from assuring you of liquidity for your deposits—you could get back your ₹10 lakh when you demanded it back, irrespective of whether your friend had repaid the bank at that time.

Banks’ Role as Financial Intermediaries

Banks have a crucial role to play in the financial system of any country. The prime objective of the financial system is to channel surpluses arising in the economy through the activities of households, corporate houses and the government, into deficit units in the economy, again in the form of households, corporate houses and the government.

The financial system comprises ‘financial markets’ and ‘financial intermediaries’.

The financial markets function as ‘brokers’ that bring the surplus and deficit units together for mutual benefit. However, the risk of lending to deficit units is borne largely by the surplus units themselves.1

The financial intermediaries, on the other hand, create ‘assets’ out of the surpluses of the economy. In doing so, they assume the risk of lending to the deficit sectors. Not only that, they assure liquidity to the surplus units who have entrusted their savings to them. Last but not least, they reduce risk with low information costs. To illustrate this aspect, let us go back to scenario two in the above example of lending to a friend. If you had to gather all the information before deciding to lend to your friend, it would have been a costly exercise. But banks can gather the information at much lower costs because (1) they have the expertise; (2) they have the experience to back their decision of lending to a similar or the same industry; (3) they have ready access to current information on the borrowers’ cash flows through observing transactions in the accounts; (4) various deposit resources are pooled to form large loans, making which are relatively cheaper for banks; (5) borrowers value their ongoing relationship with the banks and hence part with information more readily and on a regular basis; and (6) diversification of deposits over many independent assets is possible for banks.

Hence, financial intermediaries serve three useful purposes:

- They mitigate the default risk of deficit units when surplus units lend to them.

- They ensure liquidity of savings by surplus units.

- They lower information costs.

Figure 5.1 illustrates the flow of funds through the financial system.

FIGURE 5.1 FLOW OF FUNDS THROUGH THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM

Gains from Lending

Let us assume that your friend’s project, if a success, could generate ₹1 crore of annual net profit. Your deposit with the bank earns an interest of ₹1 lakh at 10 per cent interest per annum. What has the bank done? Your investment, currently earning ₹1 lakh, has been converted into an asset that has the potential of earning ₹1 crore per year! Thus, there is a net addition to the total income of the economy by ₹90 lakh per annum. The bank has also saved you substantial transaction costs—information, contracting, monitoring—if you had invested directly in the project as in scenario above, thus maximizing the net income addition to the economy. However, net addition to national income can be maximized only if bank lending is ‘efficient’—lending should be at competitive prices, at minimum transaction costs, and the financial system should be ‘integrated’2 A financial system is said to be integrated if similar loans can be made on similar terms everywhere in the economy.

Apart from adding to the entire economy’s income, lending also adds profits to individual banks. A bank can lend profitably only if it is able to take on and manage credit risk that arises from the quality of the borrower and his business. The bank also has to contend with the impact of fluctuations in interest and exchange rates on profits, as well as the liquidity risk posed by mismatch in the maturities of its liabilities and assets.3

Who Needs Credit?

Banks extend credit to different categories of borrowers for different purposes. For most of these borrowers, bank credit is the primary and cheapest source of debt financing. Both the demand and supply sides of the economy need bank credit. Consumers of goods and services constitute the demand side of the economy, and they require bank credit to enable them acquire assets such as consumer durables, housing or for plain consumption. On the supply side, the need for credit arises from the corporate and government sectors engaged in manufacturing, trading and services. These sectors require bank credit for capital investment in long-term projects and for day-to-day operations.

In more common terms, financing the demand side of the economy, the large class of consumers, is called retail banking (also termed mass banking). Financing the supply side of the economy, which is more customized in nature and calls for specialized skills, is called wholesale banking or corporate banking or class banking.

In this chapter, we will look primarily at wholesale banking or corporate banking concepts, features and practices, since these are one of the most specialized in any banking organization.

Features of Bank Credit

For a bank, good loans are its most profitable assets. And any loan is ‘good’ till the borrower defaults in repayment. In its role as a financial intermediary, the direct assumption of financial risk is the bank’s defining characteristic.

Consequently, banks have to look for higher returns. Returns come in the direct form of loan interest, or in the indirect form of fee-based ancillary services. Further, the borrowers may also contribute to generation of deposits, which, in turn, can be invested by the bank. The most prominent risk in lending is default risk (known as credit risk), which can arise due to several factors. Borrowers may default due to industry downturns and business cycles (such as in real estate) or due to specific problems related to the borrowers’ firms or activities, such as mismanagement, problems with labour, technological obsolescence and change in consumer preferences. Banks, therefore, make it a practice to set aside substantial reserves (called ‘provisions’) to compensate for anticipated losses due to credit risk.4

There can be another kind of risk associated with credit decisions-interest rate risk.5 Fluctuations in interest rates give rise to earnings volatility. Loan maturities, pricing and the methods of principal repayments all impact the timing and magnitude of banks’ cash inflows.

Keeping these prominent risks in view, risk-based capital standards require that banks maintain a stipulated amount of capital for every loan created in their books.6 This implies that banks choosing to lend to a specific borrower, group or sector must mobilize additional capital to keep growing. Banks have sought to circumvent these requirements by resorting to ‘securitization’7 or ‘off-balance sheet lending arrangements’. Under ‘off-balance sheet lending’, the bank does not directly extend credit but involves itself with the borrower either as an underwriter for arranging financing (as in ‘Loan syndications’8), or by issuing a letter of credit to import inventory rather than finance acquisition of inventory. In both cases, the bank earns a ‘fee-based income’ for its services, but creates a ‘contingent liability’ in its books.9 A contingent liability is, however, not free of risks. If the borrower defaults, the bank becomes liable, i.e., the bank’s obligation to make payment under the contract arises from the happening of a contingent event.

Types of Lending

Broadly, three types of lending can be identified:

- Fund-based lending: This is the most direct form of lending. It is granted as a loan or advance with an actual outflow of cash to the borrower by the bank. In most cases, such lending is supported by prime and/or collateral securities.10

- Non-fund-based lending: There are no funds outlays for the bank at the time of entering into an agreement with a counterparty on behalf of the bank’s customer. However, such arrangements may crystallize into fundbased advances for the bank if the customer fails to fulfil the terms of his contract with the counterparty. Most ‘contingent liabilities’ of the bank, more prominently, letters of credit (LCs) and bank guarantees (BGs), fall under this category.

- Asset-based lending: This is an emerging category of bank lending. In this type of lending, the bank looks primarily or solely to the earning capacity of the asset being financed, for servicing its debt. In most cases, the bank will have limited or no recourse to the borrower. Specialized lending practices, such as securitization or project finance fall under this category.

Fund-based advances can be further classified based on the tenure of the loans.11 The traditional approach is to make the following distinction: short-term loans, long-term loans and revolving credits. We will examine the basic features of these loans in the following paragraphs.

Short-Term Loans Typically, these are loans with maturities of 1 year or less. Most of these loans are granted with the primary purpose of financing working capital needs of the borrower, resulting from temporary build up of inventories and receivables. In the case of such loans, repayments would flow out of conversion of current assets to cash.

Sometimes, seasonal lines of credit are granted to borrowers whose businesses are subjected to seasonal sales cycles, and hence, periodic peaking of inventory and other current assets. The amount of credit is made available based on the estimated peak and non-peak funding requirements of the borrowers. The borrowers draw upon the seasonal lines of credit during periods of peak production to meet seasonal demand, and repay the loans as inventories are liquidated and cash flows from sales come in. Interest accrues only on the amounts drawn down from the line of credit.

Both the above types of loans are generally made as ‘secured loans’. This implies that the banks make the loans based on the strength of underlying securities, such as inventories, receivables and other current assets. Such securities, the values of which directly affect the amount that can be granted as loan, are called ‘prime securities’. The other type of securities backing the loan repayments is ‘collateral securities’. Such securities are not directly linked to the operations of the borrower, but are offered either in lieu of or along with prime securities, as a cushion against probable default by the borrower. The idea is that banks can liquidate these securities in the event of default and realize the amount due under the loan agreement.

A third category of short-term loans, granted for ‘special purposes’, may or may not be secured. Such loans are called ‘unsecured loans’. They may arise due to a host of reasons, including temporary but unexpected or unusual increases in current assets, or a temporary cash crunch in the borrower’s firm. Such requests are considered as falling outside the borrower’s estimated needs for short-term working capital financing, and, depending on the borrower’s creditworthiness, may be granted as ‘temporary’ or ‘ad hoc’ loans. These loans are often granted with terms and conditions different from those applicable to the assessed working capital needs of the borrower. Such loans may require full payment of interest and principal at maturity, i.e., a ‘bullet’. The term for such loans is determined by estimating the time at which the borrower can generate cash flows to make the repayment. The risk in these loans arises from a change in the assumed circumstances on which the decision to grant the loans were based.

Long-Term Loans Bank lending, which used to traditionally focus on ‘short-term’ loans, started looking at lending for periods longer than a year only from the 1930s onwards. These are called ‘term loans’ and have the following characteristics:

- Original maturities of more than 1 year.

- Repayments are structured based on future cash flows rather than on liquidation of short-term assets.

- The primary purpose of these loans could be acquisition of fixed assets (versus current assets in the case of short-term loans), or funding expansion/modernization/diversification plans of the borrower’s firm.

- The term loans may be used as substitutes for equity or for financing permanent working capital needs.

- Typically, these loans are fully disbursed at inception, and principal and interest are repaid depending on the borrower’s capacity to generate operating cash flows.

- The amount and structure of these loans will closely match the transaction being financed.

- Mostly, the securities for the term loans will be the bank’s claims on assets purchased from the term loan proceeds.

- Though banks do not customarily lend for very long periods,12 the maximum tenure (maturity) of term loans is 10 years, the average ranging between 3 and 5 years.

Thus, long-term loans are generally structured to be more adaptable to borrowers’ specific requirements.

Revolving Credits Revolving credits offer the most flexibility to borrowers. Assessed to meet the borrowers’ requirements over a period of 1 year or more, revolving credits permit drawings from the line of credit at any time, and similarly, repay the whole or part of the outstanding loans as and when cash inflows happen in the borrowers’ firms. The revolving credit is usually a secured loan, with terms and conditions as applicable to other types of loans. The amount of revolving facility granted will be based on the assessed need of borrowers, underlying securities and borrowers’ creditworthiness.

In rare cases, revolving loans are structured to convert to term loans or automatically renew on maturity. The automatic renewal facility, termed the ‘evergreen’ facility, continues till the borrower gives notice of termination. Such arrangements, needless to say, will put the banks more at risk of default than the other two types of lending.

SECTION II

THE CREDIT PROCESS

The risks involved in lending render it imperative that banks should have systems and controls that enable bank managers to take credit decisions after objectively evaluating risk-return trade offs. Whether it is consumer or commercial lending, credit decisions impact the profitability of banks, and ultimately their competitiveness and survival in the industry.

Credit decisions are by no means easy. The credit officer has to deal with conflicting objectives of increasing the loan portfolio (his targets) while maintaining loan quality (the risks inherent in the loan portfolio as well as in individual loans). He also has to balance these objectives with the bank’s profitability and market value objectives, liquidity requirements and constraints of capital. He should be able to investigate and appraise the risks inherent in every opportunity to lend, and take decisions that will fit in with the overall strategy of the bank. Above all, he should not take or lead the bank to a wrong credit decision.

Despite the availability of tools and techniques and a huge body of knowledge to support decision-making, credit decisions are largely judgmental. However well versed the credit officer is in appraising and lending to risky projects, his contribution may not suit the bank if his decisions do not fall in line with the overall strategy of the bank. Therefore, apart from their expertise in credit appraisal, the strategic role of credit officers assumes utmost importance.

Constituents of the Credit Process13

The Loan Policy To ensure alignment of individual goals of credit officers to the bank’s overall goals, banks formulate ‘loan policies’. These are written documents, authorized by individual bank’s Board of Directors, that formalize and set guidelines for lending to be followed by decision-makers in the bank.

The loan policy specifies the bank’s overall strategy for lending, identifies loan qualities and parameters, and lays down procedures for appraising, sanctioning, granting, documenting and reviewing loans. Loan policies emerge from and are fine-tuned by past experience of individual banks in extending credit, and the best practices followed in the industry. While supervising bank operations, regulators examine banks’ documented loan policies to ensure that existing lending practices conform to the organization’s objectives and acceptable guidelines. The stance taken by individual bank managements determines the extent and form of risk that the bank would be willing to take.

Box 5.1 outlines the major components of a typical loan policy.

BOX 5.1 MAJOR COMPONENTS OF A TYPICAL LOAN POLICY DOCUMENT

Loan objectives

Within the regulatory prescriptions, the loan objectives will communicate to credit officers and other decision-makers, the bank’s priorities among the conflicting objectives of liquidity, profitability, increasing business volumes, and risk and asset quality.

Volume and mix of loans

How much of the loan portfolio is to be channelled into specific industries, sectors or geographical areas, will be communicated in this section. It may also specify composition of the loan portfolio by size of loans, pricing of loans or securities. In many countries, especially developing economies, regulators stipulate targets for directed lending to certain critical sectors.

Loan evaluation procedures

Generally, uniform credit appraisal procedures are prescribed throughout the bank. The procedures would deal with all issues ranging from establishing suitability of the loan to the bank’s overall strategy and risk taking ability, to selection of borrowers, market and project risk appraisal criteria, financial statement analysis, structuring of loan agreements, documentation and post-sanction monitoring.

Credit administration

Lending involves more risks than any other banking activity. Hence, banks are careful to ensure that credit decisions are taken by experienced and knowledgeable officers, with decision-making authority as decided by the top management or the board from time to time. The loan policy should indicate the credit sanctioning powers of the officers at various hierarchical levels of the bank. Due diligence should also ensure that officers do not overstep limits fixed for their levels. Similarly, if limits fixed for decision-making are too low and conservative, the top management may have to spend more time on decision-making. If limits are too high at every level, the bank may expose itself to heightened risks.

Credit files

Credit files are important documented and updated material used for both decision-making and continuous evaluation. Sometimes, the loan policy specifically mentions the mandatory format in which information in the credit files is to be maintained.

The interest charged should reflect the credit risk in a loan. The policy may also state the returns expected for each risk group of borrowers in the bank, and specifies risk limits up to which the bank can lend. It can also specify the credit scoring system to be adopted to fix the lending rates, and circumstances under which fixed and floating rates of interest can be charged to the borrower.

The other parameters that a loan policy may specify are (1) type of collateral the bank can accept as security for the loans; (2) the extent to which the security should cover the advances made; (3) nature of margins/compensating balances14 to be maintained by various classes of borrowers; (4) limits up to which the bank can expose itself to certain sectors and borrower groups; (5) credit monitoring system that would be operative after the loan is disbursed; (6) credit to deposit ratios that the bank needs to maintain; (7) incentive schemes for loan officers; (8) loan agreement and other communication practices; (9) procedure for rescheduling/restructuring loans; (10) role of credit department in the bank; (11) role of recovery department in the bank; and (12) role of legal department in the bank.

The loan policy establishes the ‘credit culture’ that is unique to each bank. Adherence to the guidelines of the loan policy is reviewed by credit monitoring committees, and the need for periodic revision is also suggested, in keeping with the dynamic environment.

Business Development and Initial Recommendations Within the broad framework of the loan policy of the bank, and based on the bank’s goals in building its loan asset portfolio, credit officers seek to reinforce the relationship with existing customers, build new clientele and cross sell non-credit services. Though every employee of the bank, from the front office personnel to the top management, is responsible for overall business development, credit development requires a more focused approach. For one, not every prospective customer can be invited to be a borrower. There are enormous risks attached to making a bad loan than bypassing an opportunity for making a good loan.

Therefore, business development efforts for credit expansion should preferably begin with market research and detailed credit investigation. The outcome of this research will be reflected in the annual business plan of the bank, which would specify the broad industries, or areas where the bank would like to expand, and the extent to which the bank would like exposure to each industry or area.

Based on the plan, the bank embarks upon publicity for its proposed credit products in the case of retail lending, or special campaigns for attracting target customers. In the case of corporate borrowers, the credit officers formulate call programs. Once prospective credit customers are identified, credit officers try to obtain formal loan requests from these customers. The loan requests, once found acceptable in principle, would be processed further based on various documents called for, such as the prospective borrower’s financial statements, credit reports, the relevant project report and the legal resolution to borrow.

Sufficient information is sought from the prospective borrower to analyze creditworthiness. Credit appraisal is essentially an analysis of the risks or vulnerabilities in respect of the borrower and his business. The risks are analyzed with a view to determining how each of them, individually or in combination, can affect the debt servicing capacity of the borrower. A typical credit appraisal would deal with the following issues.

- What are the risks inherent in the borrower’s business? These risks are classified into market-related risks, technology-related risks, environment-related risks and so on.

- What are the antecedents of the borrower? What is his reputation and integrity? How is his track record?

- What are the financial risks inherent in the borrower’s business? Is the project economically viable? Is the project financially feasible?

- What risks are inherent in the operations of the business?

- What have the managers of the borrower firm done to mitigate these risks?

- Does the bank want to lend to this borrower in spite of the risks? If so, what steps should the bank take to ensure that debt repayments are not hampered?

- What risks will the bank have to take if it decides to fund the borrower? How does the bank propose to mitigate these risks?

The first three questions focus on appraisal of the borrower, his firm, the project for which he has sought funds and his capacity to repay. The next two questions enable the credit analyst to examine the internal management and operations of the firm. The analysis leads to a decision–to lend or not to lend? Once the analyst decides to recommend lending, the safeguards in and structure of the loan agreement has to be put in place.

Traditionally, key risk factors were analyzed using pragmatic considerations, such as creditworthiness of the borrower, security offered, prospects of the firm and longevity of the relationship. These were considered the ‘canons of lending’, and were addressed as the ‘five Cs’, (capacity, capital, collateral, conditions, character) or remembered through mnemonics such as ‘CCC’15 (capital, character, capability) or ‘PARTS’16 (purpose, amount, repayment, terms, security), or ‘CAMPARI’17 (character, ability, means, purpose, amount, repayment, insurance).

In all these models, the inherent assumption was that the borrower’s past would be indicative of the future, an assumption that may not hold well in a highly dynamic or volatile environment.

Modern credit analysis uses the traditional concepts in making subjective evaluation, along with wide use of financial ratios and risk evaluation models to determine if a borrower is creditworthy. The accent on risk evaluation implies that the banker lends only if he is satisfied that risks are mitigated to ensure that the borrower’s future cash flows (and hence debt service) will not be affected.

Broad Steps to Credit Analysis

Step 1—Building the ‘credit file’: The first step to effective credit analysis is gathering information to build the ‘credit file’. The preliminary information so obtained would throw light on the borrower’s antecedents, his credit history and track record. If the project is a Greenfield project, the credit officer will have to do a thorough research into various aspects of the project, as well as into the borrower’s financial and managerial capacity to make the project a success. If the borrower is an existing one, seeking additional credit, the information would be readily available with the credit officer. The credit file is an important tool box for the credit officer. It should contain all pertinent information on the borrower, including call report summaries, past and present financial statements, cash flow projections and plans for the future, relevant credit reports, details of insurance coverage, fixed and other assets, collateral values and security documents. The file for an existing borrower should also contain copies of past loan agreements, comments by prior loan officers and all correspondence with the customer. In the case of long standing borrowers, such credit files may run into several volumes. It is advisable for the credit officer to peruse all the volumes of the credit file before embarking on credit analysis.

Why is this step so important? One of the most vital factors in lending is assessing the borrower’s willingness and desire to repay the loan. The most sophisticated credit analysis cannot measure and, therefore, cannot establish beyond doubt the borrower’s intention to repay. The extensive information in the credit file will enable the credit officer to examine the borrower’s track record in repayment, and help in forming an opinion about the borrower’s future repayment intention and potential.

Step 2—Project and financial appraisal: Once the preliminary investigation is done, the internal and external factors, such as management integrity and capability, the company’s performance and market value and the industry characteristics are evaluated.

One of the important activities at this stage is financial analysis. An illustrative list of inputs and activities is as follows:

- Past financial statements. While the borrower’s audited financial statements are typically the starting point/ many banks additionally ask for financial statements presented in the bank’s own format. Typically, past financial statements pertain to the last 2–3 years, along with estimates for the current year.

- Cash flow statements. This statement would reveal the usage of own and borrowed funds by the borrower.

- The above data from the borrower enables the credit officer to analyze the liquidity position of the borrower/ his firm. Adequate liquidity is a vital indicator of the borrower’s financial health to the bank, as loss of liquidity through delayed cash flows or diversion of short-term funds or leakage in cash, is bound to adversely affect the borrower’s repayment capacity. Liquidity is assessed through a set of financial ratios. Most banks recast the financial statements of the borrower to reveal the true picture—for example, banks remove ageing receivables or slow moving/obsolete inventory from current assets. Hence, more detailed information is sought from the borrower before the financial statements are analyzed.

- The financial risk of an entity is measured by the debt it has incurred in the course of business compared with the owner’s stake. Banks generally stipulate maximum debt to value ratios for various categories of borrowers, beyond which the borrowers will have to increase their stake in the business to avail more bank credit. Credit officers look more to the ‘tangible net worth’ on the borrower’s books as the measure of owner’s stake in the business. ‘Tangible net worth’ represents the net worth less intangible assets, such as losses or goodwill.

- Once the borrower’s current financial health is gauged, the projections are examined. The borrower’s debt servicing capacity is determined by assessing the quality of cash flow projections given by the borrower. The experienced credit analyst questions the borrower’s projections, especially the sales projections, till he satisfies himself that they are indeed realistic, achievable, and more importantly, the cash flows are sufficient to service the debt (principal + interest). Further, sensitivity analyses are carried out on the projections to test the strength of the underlying assumptions and assess the impact on debt service capacity under various stress conditions. While every scenario cannot be adequately tested, the worst case scenario will indicate the most pessimistic outcome for the bank and it is then for the bank to decide whether it wants to undertake the risk.

- Even the most scientifically done projections cannot predict the onslaught of future uncertainties. Hence, the lender looks for a secondary source of repayment, which is provided by the collateral securities. The credit officer evaluates the strength of the collateral securities to determine the amount that can be recovered by liquidating these securities in the worst possible scenario. It is to be noted that loans should not be made based on the strength of the collateral securities alone. The securities should be treated as the second line of defence and not the raison-d’etre of the loan itself.

Step 3—Qualitative analysis: Integrity is the most important quality that the banker looks for in a borrower, and the most difficult to measure. So is assessment of the quality of the management team. However, lenders will have to make qualitative assessment of the borrower on most of the criteria mentioned in Annexure I, by evolving suitable measures. Many poor credit decisions have been the result of not knowing enough about the customer.

Step 4—Due diligence: Bypassing due diligence can be very costly for a bank. Many loans have run into problems since bankers did not take this step seriously. This is a time-consuming activity but well worth the effort. Due diligence can include checking on the borrower’s address (if a new borrower), pre-approval inspections of the borrower’s workplace, and interviews with the borrower’s competitors, suppliers, customers and employees. A comprehensive due diligence can also include reviews of technology used by the borrower, planned capital expenditures, other obligations to outsiders, credit reports from other debtors, the internal management control and information system, industrial relations, employee compensation and benefits, and environmental audit. Disclosure of contingent liabilities by the borrower is an essential part of due diligence, since any such contingent claim on the borrower would directly impact the assessed debt service capacity.

Step 5—Risk assessment: A key function of the credit officer is to identify and analyze the key risks associated with the proposed credit. All potential internal and external risks are to be identified and their severity assessed in terms of how these risks would impact the borrower’s future cash flows and hence the debt service capacity. The risk assessment would form an important input for structuring the credit facility and the terms of the loan agreement.

A sample risk classification grid has been presented in Annexure I. Why do we need risk classification criteria? They are necessary to assist lending officers in assessing the degree of default risk in a proposed loan. They also set standards for arriving at loan pricing decisions and terms of the loan agreement commensurate with the risk of loss. Once constructed, the classification can be used for comparisons over time periods for the same borrower, or can be standardized for comparisons of different loans. It is, however, important to note that the most sophisticated risk classification criteria cannot substitute the experienced judgment of the credit officer. The risk classification criteria are to be used to determine the relevance and impact of identified factors and construct a framework to examine their applicability to specific loans.

Credit rating agencies play an important role in assessing risk of bank loans. As recommended by Basel II, (see Chapter 11‘Capital-risk, Regulation and Adequacy’) external ratings are required for calibrating regulatory capital requirement. In the ‘standardized’ approach for credit risk and market risk, the risk weight of bank exposures are aligned to the external ratings of the exposures. Even in the advanced approaches, external ratings will be used by banks for assessing the efficacy of their own internal assessments. Annexure II provides an overview of credit rating agencies in India and their role in assessing risk, and its location and distribution in the financial system.

Step 6—Making the recommendation: Finally, based on a thorough analysis of the project, the borrower and the market, and after examining the ‘fit’ of the credit with the ‘loan policy’, the credit officer makes his recommendations to consider the loan favourably or reject it outright. Sometimes, in the case of clients with a long history of relationship with the bank, even if the criteria for consideration of the current proposal fall short of expectations, the credit officer can suggest procedures to improve the borrower’s financial condition and the repayment prospects. If warranted, the credit officer can also call for a revised credit proposal from the borrower. After a preliminary negotiation with the borrower, the credit officer’s recommendations would specify the credit terms, including loan amount, maturity, pricing, repayment schedule, description of prime and collateral securities and the required terms and conditions for the borrower’s compliance.

Credit Delivery and Administration Who takes the decision to lend? Depending on the size of the bank, the loan size and type of exposures planned, the final decision to lend may be taken by an authorized layer of the bank. Typically, banks fix ‘discretionary limits’—monetary ceilings up to which personnel at each level can take credit decisions—for each layer of authority starting from credit officers themselves to branch heads to senior and top management at the corporate office, including the Board of Directors. These ‘discretionary limits’ become larger as they move up the organizational hierarchy. For example, in some banks, the credit officer may have the least discretionary limit. Any request for a loan amount over and above this limit will have to be referred to the next higher layer, say the branch head, for his decision. Where the loan amount exceeds the branch head’s or territorial head’s discretion, the request is referred to the corporate office, where decisionmakers can be individual senior or top management officials or a committee of such officials. Many times, large credit exposures are referred to a top management committee for a joint decision to be later ratified by the Board. Some critical exposures are referred to the Board for a decision.

For all decision-makers above the level of loan officers, the loan officer’s appraisal forms the very basis of decision-making. Hence, the loan officer’s role in the credit decision-making process is extremely critical. Many banks create a separate channel in the hierarchy for grooming and equipping credit officers with the essential attitude and skills for the lending function.

The hierarchical levels over and above the credit officer merely review the recommendations made by the credit officer, and add their insights and comments before making the decision. It is not necessary that a favourable recommendation from a credit officer after extensive research has to be approved by the ultimate decision-maker. Accountability demands at every level of the bank require that the decision-making authority forms an independent opinion of the borrower’s creditworthiness and takes decisions accordingly in the best interests of the bank.

Some very large banks have a centralized ‘underwriting department’. This corporate service essentially sources new business for the bank and manages select existing relationships. For these select customers, this centralized department processes the credit request and conveys approval ‘in principle’, in order to cut the process and time required for a sanction through the regular process. Many large banks use customized software to evaluate credit requests. However, as already emphasized, sophisticated tools can be used as aids, and not as substitutes, for the credit officer’s or the credit sanctioning authority’s judgment.

Once a loan is approved, the officer communicates the sanction to the borrower through a formal ‘sanction letter’. The sanction letter is generally in the form of a ‘loan agreement’, to be signed by the borrower(s) and guarantors, if any. The loan agreement contains the following essential features:

- Nature/type of credit facility.

- Interest/discount/charges as applicable.

- Repayment terms.

- Stipulations regarding end use of each facility.

- Additional fees applicable such as processing fees, closing fees or commitment fees.

- Prime security for each credit facility.

- Full description of the collateral securities.

- Details of personal/third party guarantees.

- Covenants—terms and conditions under which the loan facilities are being granted.

- Events of default and penal provisions.

Loan Documentation Different types of borrowers and different types of security interests necessitate loan documentation procedures that would be valid in a court of law. Accordingly, once the loan agreement is signed, the borrowers and guarantors execute the loan documents. The security interest is said to be ‘perfected’ when the bank’s claim on the borrower’s assets forming the security is senior to that of any other creditor.

If the borrower defaults on a secured loan, the bank has the right to take possession of the assets and liquidate them to recover its dues. Proper loan documentation secures this right.

Terms and Conditions of Lending These are very important ingredients of any loan agreement. The bank derives control over the borrower’s operations and also mitigates the risks of lending through this part of the loan agreement. The terms and conditions comprise of three distinct portions:

- Conditions precedent: These are requirements that a borrower should satisfy before the bank acquires the legal obligation to disburse the loan amount. Some illustrative and commonly used conditions precedent are auditor’s certificate for having brought in the committed capital amount, relevant legal opinions sought for and board resolution to borrow. An important condition precedent is a material adverse change clause that covers the financial statements and projections. The clause protects the bank in the event of a material change occurring after the loan is sanctioned but prior to disbursement, which may jeopardize the bank’s chances of recovery of its dues from the borrower.

- Representations and warranties: The assumptions based on which credit appraisal is done and the bank has agreed to lend money, emanate from the information the borrower himself provides to the bank. In executing the loan agreement, the borrower is assumed to confirm the truth and accuracy of the information provided to the bank. Any misrepresentation constitutes an event of default and renders the agreement invalid. The principal representations and warranties include the following:

- All information provided, including financial statements, is true and correct.

- The borrower is authorized by law to carry on the business.

- The signatories to the loan agreement are authorized to do so, and their commitment is legal and binding.

- All statutory obligations, such as payments of taxes, have been met.

- There are no major legal proceedings pending or threatened against the borrower.

- There are no factual omissions or misstatements in the information provided.

- Collateral and prime securities are unencumbered.

The third and most negotiated part of the loan agreement is the ‘covenants’ of the borrower.

These are the operative part of the terms and conditions, and set standards and codes of conduct for the borrower’s future business, as long as the borrower is indebted to the bank. The covenants are used by astute credit officers to mitigate the risks of the borrower’s business, in order that credit risk is mitigated for the bank. Covenants are sacred, and any violation will be treated as an ‘event of default’. They normally take two distinct forms— ‘affirmative’ and ‘negative’.

- Affirmative covenants are those actions the borrower should take to legally and ethically carry on the business. Illustrations of affirmative covenants include the following:

- Ensuring that the funds are applied for the purpose for which they were intended.

- The indicators ensuring financial health, such as a strong current ratio, a safe debt to equity ratio, appreciable sales growth and a healthy return on equity (ROE).

- Ensuring that proper records and controls are maintained within the firm.

- Ensuring compliance with the law, and reporting requirements required under statute.

- Ensuring compliance with information requirements by the bank, and periodic reporting of financial and operating performance.

- Ensuring that the prime and collateral securities are adequately insured.

- Ensuring that property, fixed assets and other assets belonging to the borrower’s firm are properly maintained.

- The bank will retain its right of inspecting the assets offered as security at any time, without prior notice.

- Negative covenants place clear and significant restrictions on the borrower’s activities. Such covenants are intended to pre-empt managerial decisions that may adversely impact cash flows and hence jeopardize the borrower’s debt service capacity. Borrowers would generally be more inclined to negotiate negative covenants, since they may be perceived as restricting operational autonomy. Some typical negative covenants are as follows:

- Limiting further capital expenditure.

- Limiting investment of funds.

- Restricting additional outside liabilities.

- Restricting investment in subsidiaries, other businesses.

- Restricting sale of assets, subsidiaries.

- Restricting dividend payouts.

- Restricting prepayment of other debts.

- Limits on debt in the capital structure.

- Restrictions on mergers or share repurchase.

- Restriction on starting or carrying on other business.

- Restriction on encumbering assets (negative lien).

The last restriction, negative lien,18 is a covenant that is widely used by banks to prevent the borrower from creating encumbrances on assets, so as to benefit other creditors.

The bank may employ these restrictions and limitations selectively, to ensure that the risks in the borrower’s business are mitigated. The ultimate objective of these restrictions is to ensure that the borrower’s financial health is not impaired, and the bank’s dues are paid on time.

Events of Default Such events, when they happen, may trigger the end of the banker–borrower relationship. An illustrative list of situations that may lead to an event of default include the following:

- Failure to repay principal when due.

- Failure to service interest payments on due dates.

- Failure to honour a covenant.

- Misrepresentation of facts.

- Reneging on declarations made under representations and warranties.

- Diversion of funds without bank’s knowledge to other creditors or other accounts of the borrower.

- Change in management or ownership structure.

- Bankruptcy or liquidation proceedings.

- Falsification or tampering with records.

- Impairment of collateral, or entering into invalid agreements.

- Material adverse changes that drastically change the assumptions under which the loan agreement was entered into.

- All other force majeure events that imperil debt service.

The happening of which event of default may signify the end of the banker–borrower relationship is left for the banker to decide on the merits of each case. Under certain circumstances, where the risks of such events are considered less significant, the loan agreement can provide the borrower a grace period within which to rectify the breach of a covenant. In case the borrower is unable to rectify the breach within the grace period, the bank can downgrade or recall the advances made; agree for the take over of the borrowing account by another bank; or, if the borrower is not in a position to repay the bank’s dues, enforce the securities and liquidate the outstanding advance.

In case of the third scenario given above, the bank will initially set off any unencumbered deposits of the borrower19 or cash margins20 against the advances outstanding. It will then sell off the securities to realize its dues or invoke the outside guarantees till the advance is completely liquidated.

Since the banker–borrower relationship is generally considered valuable by both parties, banks do not act in haste in the event of default.

Updating the Credit File and Periodic Follow-Up The credit file has to be continuously updated throughout the above process. Further, once the loan is disbursed, the following activities have to be carried out either by the credit officer himself or a team designated for the purpose:

- Process loan payments and send reminders in case loan payments are received late. The simple practice of reminding the borrower for every payment not received on due date, would ensure that defaults are noticed on time by the bank and timely action taken in case defaults persist, ultimately preventing a credit risk to the bank.

- The borrower will have to submit updates of financial performance periodically or as per the accounting practices in force. The bank can call for financial data at any point of time if it feels that the borrower’s financial health deserves mid-course scrutiny.

- The bank can call on the borrower at any time, even without prior intimation. When the bank’s representative visits the borrower, the primary objective will be to ensure that the borrower’s activities are in accordance with the bank’s expectations.

Credit Review and Monitoring This is the most important step in credit management, and one that lends value to bank financing. Banks that have succeeded in credit management, and hence reduction of credit risk, are those that have separated credit review and monitoring from credit analysis, execution and administration.

The credit review and monitoring process is typically bifurcated into the distinct functions of monitoring the performance of existing loans and problem accounts.

Monitoring performance of existing loans is done in two ways. One is a continuous monitoring of the transactions in the accounts of the borrower. This is best done at the office from which the credit has been disbursed. The credit officers at the disbursing office have to be alert to symptoms exhibited by day-to-day operations in the borrower’s loan account, and send warning signals to the borrower if they detect signs of incipient deterioration of financial health or misdemeanour.21 The second type of monitoring will be done through external or internal audit teams, and will be periodic or continuous, depending on the size of credit exposures or the importance of the credit disbursing office in the bank. The deficiencies in loan documentation or conduct uncovered by the audit team will have to be rectified by the credit team. The deficiency could be rectified simply by getting signatures on loan documents or filing the required statutory returns for perfecting the security. If the audit team points out violation of any loan covenant, then the credit team can persuade the borrower to fall in line.

However, what causes most concern would be deterioration in the financial condition of the borrower, which is manifested as the inability of the borrower to meet debt service requirements. Such accounts would be put on a ‘watch list’ and monitored closely, so that they do not turn ‘non-performing’.22 Sometimes, banks will have to modify the repayment terms in order to increase the probability of repayment. Such modified terms include restructuring interest and principal payments to suit the current cash flows of the borrower, or lengthening maturity of the loans. In such cases, the bank may also seek additional securities or additional capital from the borrower to compensate for the increased credit risk. It would be prudent to separate the loans under restructuring from the general credit stream, so that monitoring would be made more intense. Similarly, a separate set of specialists would man the credit monitoring or restructuring function.

In some cases, the borrower’s financial condition deteriorates to such an extent that the loan will have to be ‘recalled’. In such cases, liquidation of assets or take over by another bank willing to take on the risk will be considered. It is more likely that the former action will have to be instituted. If all other avenues of restructuring and forbearance fail, the bank would resort to legal action. Once legal action is under way, the borrower loses the option to restructure the loans or be rehabilitated back to financial health. At this stage, many borrowers opt for ‘out of court settlement’, thus avoiding long and protracted legal hassles.

SECTION III

FINANCIAL APPRAISAL FOR CREDIT DECISIONS

Though several qualitative factors play a role in a credit decision, a major influencing factor is the financial health of the borrower as brought out by the financial appraisal. We have seen in the previous section that the credit officer uses techniques, such as financial ratio analysis, cash flow analysis and sensitivity analysis to assess the achievability of the projections. How these techniques are employed in appraising various categories of loans will be dealt with in this section.

Financial Ratio Analysis

Most large banks begin financial analysis with a standardized spreadsheet or format, where the balance sheet and income statement data, past and future, are rearranged in a consistent format to facilitate comparison over time and benchmark with industry standards. The rearrangement, and sometimes reclassification, is necessary not only for consistency but also for throwing up potential risks to the borrower’s financial health.

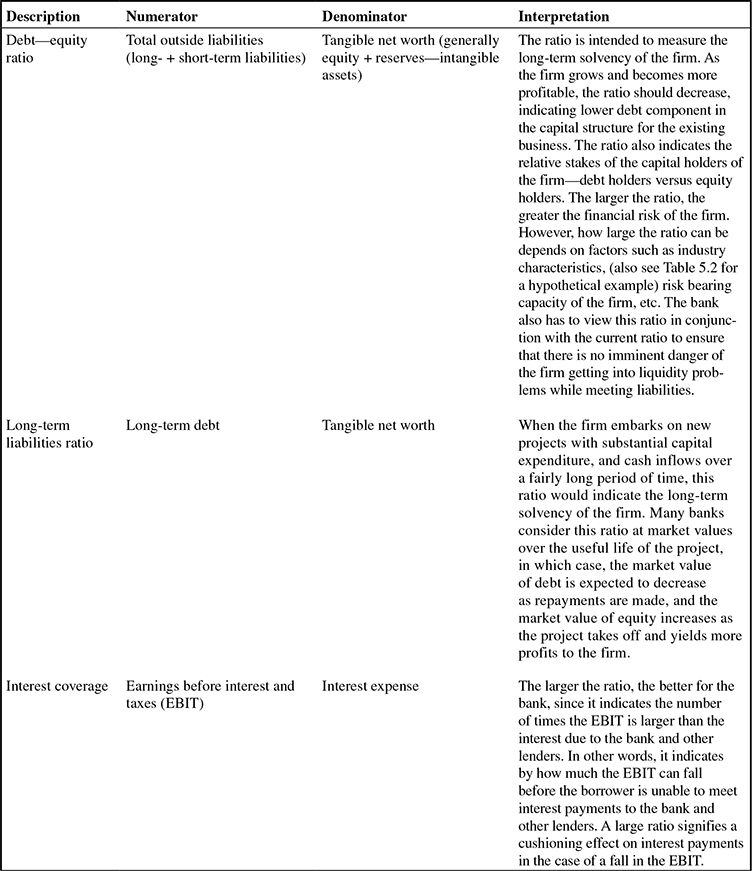

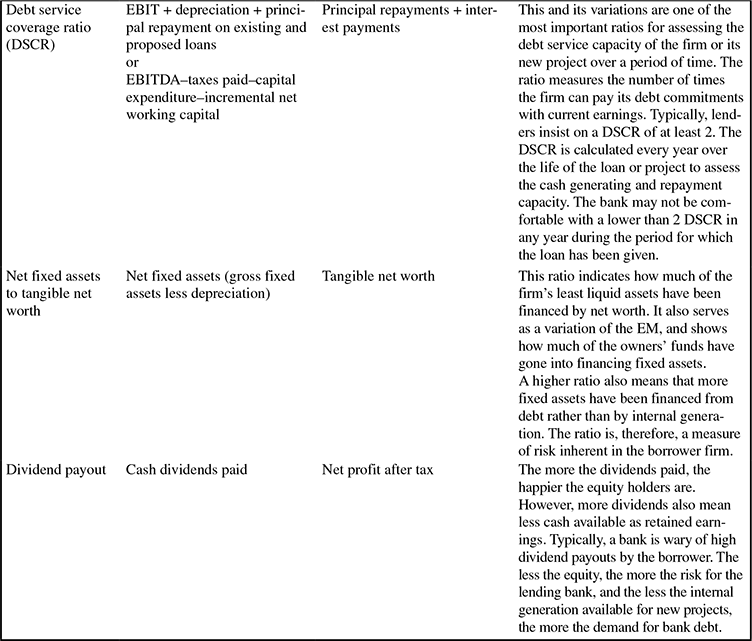

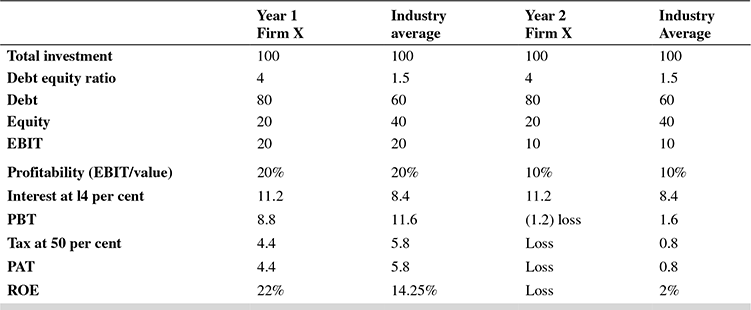

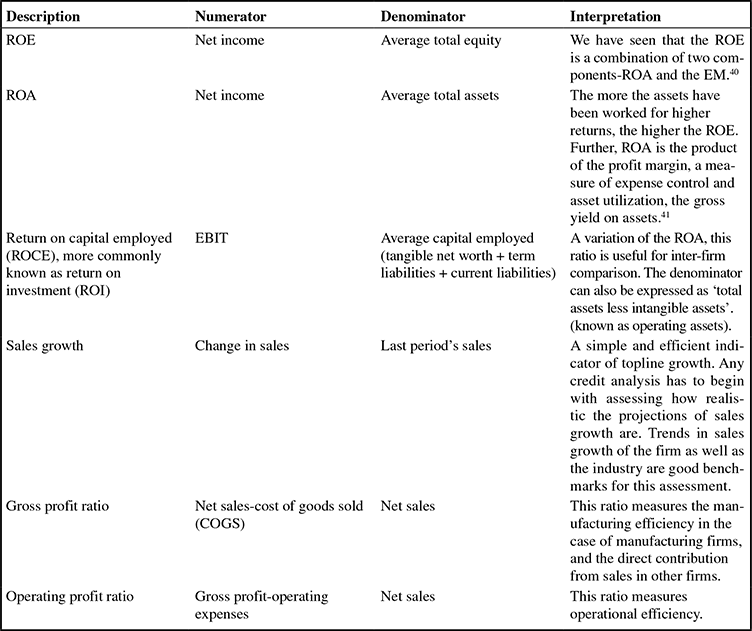

Most credit analysts use five broad categories of ratios—liquidity, profitability, leverage, operating and valuation. Liquidity ratios indicate the borrower’s ability to meet short-term obligations, continue operations and remain solvent. Profitability ratios indicate the earning potential and its impact on shareholders’ returns. Leverage ratios indicate the financial risk in the firm as evidenced by its capital structure and the consequent impact on earnings volatility. Operating ratios demonstrate how efficiently the assets are being utilized to generate revenue. Finally, valuation ratios extend beyond historical accounting measures to depict a realistic ‘value’ of the borrower. An illustrative list of commonly used financial ratios is presented in Annexure III.

Common Size Ratio Comparisons

Many banks may additionally use common size ratio comparisons. Such comparisons are valuable since they are independent of firm size, thus facilitating inter-firm comparisons in the same industry or line of business. However, the analysis should be able to spot the outliers, such as firms whose financial structure is vastly different from the typical firm in the industry. For example, a firm with leased assets would show a different asset ratio in an industry in which firms typically own substantial fixed assets. Hence, common size analysis is generally used along with ratio analysis as described above, to lead to better insights about the borrowing firm’s financial strength.

Cash Flow Analysis

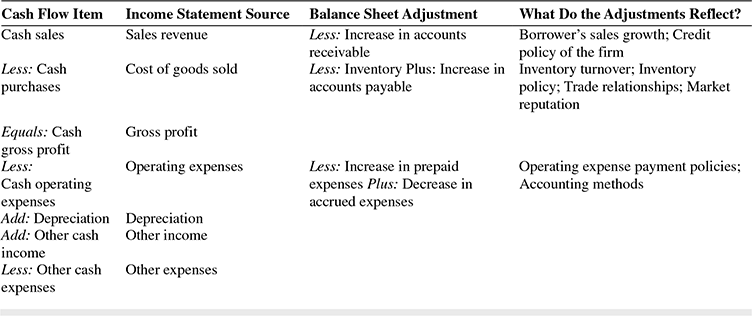

While the income statement of the borrower provides vital information, it also contains accounting adjustments and non-cash expenses. To get a clearer picture of the borrower’s capacity to repay, the bank will have to convert the income statement into a cash flow statement, or call for a cash flow statement from the borrower.

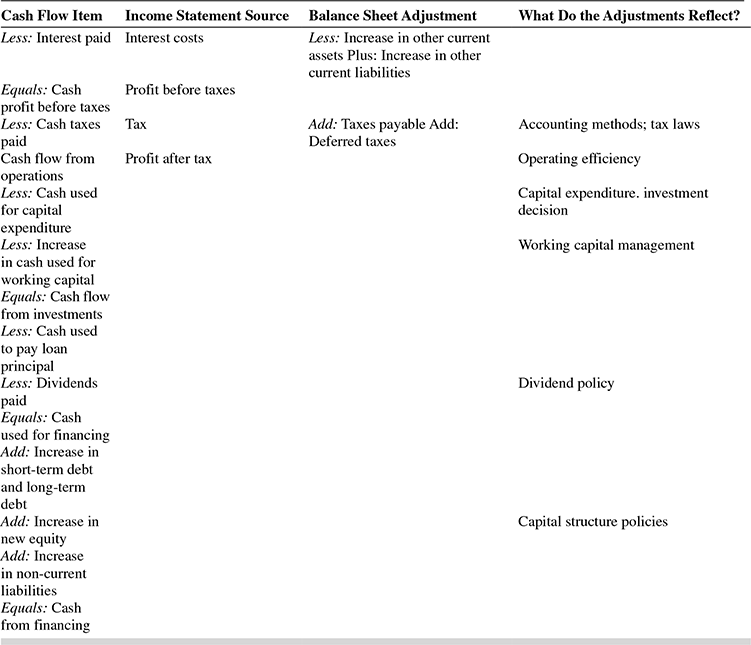

Typically, the statement of cash flows is divided into four parts—cash from operating activities, cash from investing activities, cash from financing activities and cash. The intent is to distinguish between accounting profits as measured by net income in the income statement and the firm’s various activities that affect cash flows, but are not reported in the income statement. Annexure IV provides a methodology to reconcile the income statement to its cash equivalent. The vital analysis here is to determine how much cash is generated from the firm’s activities, and whether it is sufficient to cover loan repayments and interest payments. It is expected that a firm with prudent financial management would repay short-term loans from liquidating inventories and receivables, and long-term loans from surpluses after meeting financing costs, increase in net working capital (NWC) and capital expenditure.

SECTION IV

FUND BASED, NON-FUND BASED AND ASSET BASED LENDING—FEATURES AND POPULAR FORmS

Though classified under the single nomenclature—loan—on the bank’s balance sheet, every loan or class of loans is unique. Each loan or type of loan has distinguishing features based on the purpose, the collateral, the repayment period and the borrower profile. We will examine the predominant characteristics of some popular loan types from the points of view of the borrower as well as the credit officer.

Fund Based Lending

Loans for working Capital

Banks are generally considered primary lenders to working capital requirements of firms, small and large. The rationale for banks having built up considerable expertise in funding short-term working capital is explained by the nature of bank liabilities, which are essentially short-term in nature.

A firm’s Net Working Capital (NWC) is measured as the difference between its current assets and current liabilities. If a firm’s working capital is positive, it implies that its current assets exceed its current liabilities, i.e., its current assets have been partly financed by ‘spontaneous liabilities’, such as trade creditors, and short-term bank debt and other current debt, and partly by long-term funds, including equity. A positive NWC is construed as a sign of healthy liquidity in the firm, since it is assumed that the liquidation of current assets at any point of time would enable the firm to pay off its current creditors fully.

Every firm begins by investing cash in current assets. Manufacturing firms invest in raw material that would be converted to finished goods to be sold in the market. Retail firms invest in merchandize for display at their showrooms. Service firms need cash for operations and office supplies. Almost all firms encourage credit sales to stimulate growth. Thus, there is a time lag between the investment of cash and the realization of cash from sales. The longer the firm takes to complete the cash-to-cash or ‘working capital’ cycle, the longer the firm has to wait to get back its cash investment. During this time lag, operations have to continue. The firm will have to continue investing in raw material or merchandize or day-to-day expenses. Where will the cash for this investment come from? As noted earlier, cash for operations will have to come from external creditors or internal generation. Working capital management is, therefore, a continuous process.

Each type of business depends on appropriate financing methods to stimulate investment and growth. Some firms depend on trade credit23 to finance the current assets—that is, they defer payment for inputs, in agreement with the supplier, for a specified number of days within which they hope to realize cash from sales. Some firms additionally defer expenses till the cash comes in from sales. However, the majority of firms depend on bank debt to manage the need for working capital. Thus, bank debt is a predominant source of funding working capital for all types of businesses and borrowers.

How much can a bank lend for working capital? The amount of loan will depend on the envisaged ‘working capital gap’ (WCG), determined by the borrower’s decision to take trade credit offered, or defer payment of certain accrued expenses. In balance sheet terms, this would represent the projected current assets less current liabilities, without bank borrowings being taken into account. The working capital gap represents the borrower’s need for cash for uninterrupted operations, after taking into account sources of funds available in the natural course of business also called ‘spontaneous liabilities’. The bank, however, will not finance the entire working capital gap. It will expect that the borrower brings in his stake to fund the gap. This is called the ‘margin’. Bank debt will, therefore, typically amount to the working capital gap less the margin.

Many businesses find that their working capital fluctuates over time. The reasons could be unexpected fluctuations in demand, changes in market dynamics or seasonality. Of these, seasonal sales are the easiest to predict, and firms build up inventories temporarily and incur higher operating expenses in time for the peak sales season. During the off-season, working capital needs increase since the inventory has already been invested in, peak sales have not taken place and cash flow from receivables will happen only when the inventories are liquidated. If seasonal patterns are discernible, the bank assesses working capital needs as ‘peak level’ and ‘non-peak level’. Thus, two sets of working capital assessments would be required.

An important point to be noted here is that most firms have a stable level of working capital in the system, irrespective of seasonal and other fluctuations. In other words, just as fixed assets are at a predictable level, there are always some inventories, accounts receivable and other current assets that form a permanent part of the business. The only difference between the fixed assets and these ‘permanent’ current assets is that the latter changes its composition, as and when inventories are sold off and replaced, accounts receivable are realized and replaced with fresh ones, and so on. This ‘permanent’ working capital need, every year, is approximately equivalent to the minimum level of current assets minus the minimum level of current liabilities, without taking into consideration short-term bank debt and installments of long-term debt repayable in the short term (within the next 12 months). This difference reflects the requirement of long-term debt or equity financing for the ‘permanent’ current assets. It is important for borrowing firms and banks to be able to assess such ‘permanent’ working capital requirements and fund them with long-term investment. The increase over this ‘permanent’ working capital base due to sales growth would be financed through short-term credit from banks.

Working capital loans are structured as loans against the prime securities of inventories and/or book debts or as credit limits against bills raised on buyers of the goods and services of the borrowing firm. The price of the loan (the interest rate charged) depends on the additional securities available as collateral, and the credit score rating24 of the borrower. The repayment of the loan should closely match the working capital cycle, and the covenants should be able to mitigate the risks and vulnerabilities in the borrower’s business and financials.

It is extremely important for the bank and the borrower to assess the working capital requirements accurately. A mistake often made by inexperienced credit officers is granting a loan for a larger amount or for a longer maturity than what is required, especially to ‘first class’ customers. In a purpose-oriented loan, such as for working capital, irrespective of the standing of or relationship with the borrower, it is imperative to estimate funding needs accurately in order to help the borrower’s business and minimize the bank’s risks. Both under- and overestimation have their pitfalls. If the working capital need is overestimated, the borrower may not use the additional money judiciously, or may purchase assets over which the bank does not have lien.25 If the working capital is underestimated, the borrower may face a liquidity crunch during the operational cycle and may have to re-approach the bank for additional loan or borrow from outside sources at exorbitant rates. In both cases, the bank faces default risk by the borrower.

Loans for Capital Expenditure and Industrial Credit

Firms need to invest periodically in capital assets to expand, modernize or diversify their business. In such cases, their credit needs will extend beyond a year. ‘Term loans’ are the preferred choice in such cases—with maturities of more than 1 year, repayment spread over the life of the asset or depending on the repaying capacity of the borrower. Most term loans are granted for purposes, such as a permanent increase in working capital (as discussed earlier) or for purchase of fixed assets or to finance start up costs for a new project. They generally carry maturities ranging from over 1–7 years. Though banks can, in theory, finance longer maturities, in practice they do not find it prudent to do so, because of the typically short- to medium-term maturity of bank liabilities. Lending for longer maturities may create a mismatch between asset and liability maturities and lead to a liquidity problem in banks.26

Since repayment runs into several years, the bank’s decision to lend would be based more on the long-term cash generation capacity of the borrower firm or the assets being invested in. The benchmark ratio used predominantly is the debt service coverage ratio (DSCR),27 the minimum desirable level generally pegged at 2. The bank typically would require collateral for long-term lending, more as a secondary source for repayment in case of borrower default.

The characteristics of term loans are determined by the use of the loan amount. In the case of a term loan for purchase of a capital asset, the cost of the asset less a suitable margin is disbursed in full (in most cases direct to the supplier of the equipment) after the loan agreement is executed. The repayment terms are a function of the useful life of the asset, and the borrower’s capacity to generate cash flows sufficient to service the debt. The interest charged reflects the bank’s perception of the default risk of the borrower and the collateral liquidation value over the duration of the loan. The covenants are more stringent than for working capital loans, since term loans extend over several years, and the borrowers may tend to dilute the negotiated terms. From the bank’s side too, the credit officer who was instrumental in getting the loan sanctioned may no longer be available, and loan agreements may become unenforceable for lack of clarity.

Term loan repayments and interest payments could be structured in any of the following ways:

- Repayments in fully amortized equal annual/half yearly/quarterly installment. Each periodic repayment will include interest and principal in varying amounts. The installment are treated as annuities and equated to the present value of principal plus interest to arrive at the installment. Interest is recovered in full in every instalment, and the remaining amount of the installment is taken towards principal repayment. As the principal gets repaid, the interest component, calculated on declining principal balances, decreases, and the principal component increases. Thus, in this method, the amount of payment per period remains constant, but the composition of the payment (principal and interest) varies from payment to payment.

- Repayment of principal in equal installments over the designated period, with interest calculated separately on declining balances. In this case, the amount of debt service will vary from period to period. In contrast to the annualized method of repayment, each periodic payment in this mode will vary, but the amount of principal will remain constant.

- Occasionally, the loan agreement may call for ‘balloon repayments’. In this case, the borrower is required to service only the periodic interest over the period of the loan. The entire principal amount becomes due only on maturity (also called a ‘bullet loan’). The difference between a ‘bullet’ and ‘balloon’ repayments is that in the case of ‘bullet repayment’ 100 per cent of the principal is due only at maturity while in the latter case, the credit (interest and principal) gets partially repaid during the term and presents lumpy repayment at maturity.

- In rare cases, a variation of the above method is used. The principal and interest are amortized over a very long period, say 25 to 30 years. At the end of the period, the remaining principal amount is repaid in full.

- For construction loans or project loans, the agreed amount is released in stages, as and when progress is shown in construction/the project.

Loan Syndication28

Large projects need enormous funding requirements. It may not be possible for one bank to finance the project requirements, from the viewpoint of both capital regulations and the risk of exposure. For the banks arranging the syndication and participating in it, syndication can be a source of substantial fee income as well. In essence, arranging a syndicated loan allows the lead bank to meet its borrower’s demand for loan commitments without having to bear the market and credit risk alone, and also earn non-interest income in the process.

Syndicated loans are credits granted by a group of banks to a borrower. They are hybrid instruments combining features of relationship lending and publicly traded debt. They allow the sharing of credit risk between various financial institutions without the disclosure and marketing burden that bond issuers face.

Syndicated credits are a very significant source of international financing, with signings of international syndicated loan facilities accounting for no less than a third of all international financing, including bond, commercial paper and equity issues. Increasing trends of privatizations in emerging markets have enabled banks, utilities and transportation and mining companies from these regions to displace sovereigns as the major borrowers. However, and understandably so, the amount of international syndicated loan facilities, showed a decline since 2007. Quarters 2 and 3 of 2009 have shown a slight pick up, indicating confidence returning to the market (Source: BIS locational statistics, December 2009).

In a syndicated loan, two or more banks agree jointly to make a loan to a borrower. Every syndicate member has a separate claim on the debtor, although there is a single loan agreement contract. The creditors can be divided into two groups. The first group consists of senior syndicate members and is led by one or several lenders, typically acting as mandated arrangers, arrangers, lead managers or agents. These senior banks are appointed by the borrower to bring together the syndicate of banks prepared to lend money at the terms specified by the loan. The syndicate is formed around the arrangers—often the borrower’s relationship banks—who retain a portion of the loan and look for junior participants. The junior banks, typically bearing manager or participant titles, form the second group of creditors. Their number and identity may vary according to the size, complexity and pricing of the loan as well as the willingness of the borrower to increase the range of its banking relationships. These bank roles have been enumerated above in decreasing order of ‘seniority’, and the hierarchy plays a decisive role in determining the syndicate composition, negotiating the pricing and administering the facility.

Junior banks typically earn just a margin and no fees. However, they may find it advantageous to participate in a syndicated loan—they may lack origination capability in certain types of transactions, geographical areas or industrial sectors, or a desire to cut down on origination costs. For these banks participation is also relationship building with the borrower who may reward them later with more profitable and prestigious business opportunities.

The Box 5.2 shows an illustrative structure of fees in a syndicated loan.

It is not mandatory that the lead arranger has to take a share in the credit exposure to the borrower. However, lead banks in practice do take a major share in credit exposures since their participation sends a strong signal to other participants that the borrower is creditworthy.

The mandated arrangers run two types of risks in syndication, assuming that the arrangers intend taking a major share in the syndicate’s credit exposure. One is a ‘syndication risk’, arising out of under-subscription by participating banks in the syndicate. The credit requirements that have not been tied up will have to be entirely taken up by the lead bank/s. Once the syndicate is formed, the participating banks, including the arrangers, take on the credit risk—the risk that the borrower may default on debt service.

Therefore, before taking a decision to bid for the mandate, the relationship bank will have to do a thorough appraisal of the project and its prospects.

BOX 5.2 STRUCTURE OF FEES IN A SYNDICATED LOAN29

| Fee | Type | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Arrangement fee | Front-end | Also called praecipium. Received and retained by the lead arrangers in return for putting the deal together. |

| Legal fee | Front-end | Remuneration of the legal adviser. |

| Underwriting fee | Front-end | Price of the commitment to obtain financing during the first level of syndication. |

| Participation fee | Front-end | Received by the senior participants. |

| Facility fee | Per annum | Payable to banks in return for providing the facility, whether it is used or not. |

| Commitment fee | Per annum charged on undrawn part | Paid as long as the facility is not used, to compensate the lender for tying up the capital corresponding to the commitment. |

| Utilization fee | Per annum charged on drawn part | Boosts the lender’s yield: enables the borrower to announce a lower spread to the market than what is actually being paid, as the utilization fee does not always need to be publicized. |

| Agency fee | Per annum | Remuneration of the agent bank’s services. |

| Conduct fee | Front-end | Remuneration of the conduct bank* |

| Prepayment fee | One-off if prepayment | Penalty for prepayment. |

*The institution through which payments are channelled with a view to avoiding payment of withholding tax. One important consideration for borrowers consenting to their loans being traded on the secondary market is avoiding withholding tax in the country where the loan is deposited.

Loans for Agriculture

Loans for agriculture are similar to other types of loans in the following respects:

- Most of the loans for agriculture are short-term loans.

- Agriculture being seasonal in nature, the norms for seasonal industries are applicable.

- They can be likened to working capital loans, in that the loan is used for purchase of inventory, such as seeds, fertilizer and pesticides, and also to pay operating costs.

- The sales are realized when the harvested crops are sold in the market.

- Long-term loans for agriculture are given for investment in land, equipment or livestock.

- Loans are paid out of cash flows arising from sale of crops harvested or produced from livestock.

The fundamental difference between loans for agriculture and other loans arises from the fact that agriculture is a vital national priority in many developed and developing countries. The governments and central banks of these countries have framed policies and institutional support systems to ensure that banks are involved in lending to this important sector, even when it appears that the sector may incur losses for a particular period.

Therefore, though loans for agriculture are to be assessed on similar lines as other loans, they are to be treated differently in terms of the outcome of such lending. Most countries have framed elaborate policies and institutional framework to ensure that agriculture and its allied activities are supported by banks.

Loans to Consumers or Retail Lending

Individual consumers generally seek bank finance to purchase durable goods, education, medical care, housing and other expenses. The average loan per borrower is small in relation to the bank’s lending to corporate or business borrowers. Most loans have repayment periods ranging from 1–5 years, can be longer in the case of housing loans, carry fixed interest rates and are repaid in equal installments. Individual consumers are generally seen as more prone to defaulting on loan repayment commitments than corporate borrowers. Interest rates on consumer loans are, thus, higher to compensate for the higher default risk. However, the loss to the bank when an individual customer defaults is not as great as when a corporate borrower does.