Principles of knowledge management

Introduction

It is traditional to start a book of this type with the discussion of ‘what is knowledge’?, and ‘what is knowledge management’?. If you are already quite clear about the topic, then this chapter is not for you. However, there is often still some confusion over the definitions of, and fuzzy boundaries between, knowledge management, information management and data management. The two latter disciplines are well established; people know what they mean, people are trained in them, there are plenty of reference books that explain what they are and how they work. Knowledge management, on the other hand, is a relatively new term and one that requires a little bit of explanation. If you would rather jump on to the practical applications, start at Chapter 2 and come back to Chapter 1 another day.

The greater part of Chapter 1 necessarily covers much of the same ground as the corresponding sections in Milton (2004)1 and in Young (2009).2 If you own and have read these two books, you can move on to Chapter 2.

What is knowledge?

Knowledge (according to Peter Senge3) is ‘the ability to take effective action’ (the Singapore Armed Forces further refine this definition as ‘the capacity to take effective action in varied and uncertain situations’). Knowledge is something that only humans can possess. People know things and can act on them; computers can’t know things and can only respond. This ability to take effective action is based on experience and it involves the application of theory or heuristics (rules of thumb) to situations – either consciously or unconsciously. Knowledge has something that data and information lack, and those extra ingredients are the experience and the heuristics (Figure 1.1).

Knowledge is situational and what works in one situation may not work in another.

As an illustration, consider the link between data, information and knowledge as they are involved in decision-making in a marketing organisation:

![]() The company pays for a market research survey, conducting interviews with a selection of consumers in several market segments. Each interview is a datapoint. These data are held in a database of survey responses.

The company pays for a market research survey, conducting interviews with a selection of consumers in several market segments. Each interview is a datapoint. These data are held in a database of survey responses.

![]() In order for these data to be interpreted, they need to be presented in a meaningful way. The market research company analyses the data and pulls out trends and statistics that they present as charts, graphs and analyses.

In order for these data to be interpreted, they need to be presented in a meaningful way. The market research company analyses the data and pulls out trends and statistics that they present as charts, graphs and analyses.

![]() However, you need to know what to do with this information. You need to know what action to take as a result. Such information, even presented in statistics and graphs, is meaningless to the layman, but an experienced marketer can look at it, consider the business context and the current situation, apply their experience, use some theory, heuristics or rules of thumb, and can make a decision about the future marketing approach. That decision may be to conduct some further sampling, to launch a new campaign, or to rerun an existing campaign.

However, you need to know what to do with this information. You need to know what action to take as a result. Such information, even presented in statistics and graphs, is meaningless to the layman, but an experienced marketer can look at it, consider the business context and the current situation, apply their experience, use some theory, heuristics or rules of thumb, and can make a decision about the future marketing approach. That decision may be to conduct some further sampling, to launch a new campaign, or to rerun an existing campaign.

The experienced marketer has ‘know-how’ – he or she knows how to interpret market research information. They can use that knowledge to take the information and decide on an effective action. Their knowhow is developed from training, from years of experience, through the acquisition of a set of heuristics and working models, and through many conference and bar-room conversations with the wider community of marketers.

Knowledge that leads to action is ‘know-how’. Your experience, and the theories and heuristics to which you have access, allow you to know what to do, and to know how to do it. In this book, you can use the terms ‘knowledge’ and ‘know-how’ interchangeably.

In large organisations, and in organisations where people work in teams and networks, knowledge and know-how are increasingly being seen as a communal possession, rather than an individual possession. In some companies it will be the communities of practice that have the collective ownership of the knowledge, while in others it will be the regional sales teams that have the collective ownership. Such knowledge is ‘common knowledge’ – the things that everybody knows. This common knowledge is based on shared experiences and on collective theory and heuristics that are defined, agreed and validated by the community.

Tacit and explicit knowledge

The terms tacit and explicit are often used when talking about knowledge. The original author, Polyani (1966),4 used these terms to define ‘unable to be expressed’ and ‘able to be expressed’ respectively. Thus, in the original usage, tacit knowledge means knowledge held instinctively, in the unconscious mind and in the muscle memory, which cannot be transferred into words. Knowledge of how to ride a bicycle, for example, is tacit knowledge, as it is almost impossible to explain verbally.

Following the seminal text by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995)5 these original definitions have become blurred, and tacit and explicit are often used to describe ‘knowledge which has not been codified’ and ‘knowledge which has been codified’ (or ‘head knowledge’ and ‘recorded knowledge’ respectively). This latter definition is a more useful one in the context of knowledge management within organisations, as it defines knowledge based on where it exists, rather than on its intrinsic codifiability. So, knowledge that exists only in people’s heads is often termed tacit knowledge, and knowledge that has been recorded somewhere is termed explicit knowledge. Knowledge can therefore be transferred from tacit to explicit, according to Nonaka and Takeuchi.

There is a wide range of types of knowledge, from easily codifiable to completely uncodifiable. Some know-how, such as how to cook a pizza, can be codified and written down; indeed, most households contain codified cooking knowledge (cookery books). Other know-how, such as how to whistle or how to dance the tango, cannot be codified, and there would be no point in trying to teach someone to dance by giving them a book on the subject.

Sales and marketing knowledge comprises a wide range of codifiability. Some of it can never be fully written down, e.g. how to establish a lasting relationship with a client, and must be transferred through coaching and role-play, while some of it can be easily codified into company guidelines.

What is knowledge management?

If knowledge is a combination of experience, theory and heuristics, developed by an individual or a community of practice, that allows decisions to be made and correct actions to be taken, then what is knowledge management? Larry Prusak of McKinsey Consulting says, ‘It is the attempt to recognise what is essentially a human asset buried in the minds of individuals, and leverage it into a corporate asset that can be used by a broader set of individuals, on whose decisions the firm depends’ (Prusak, verbal communication). Larry is suggesting here that the shift from seeing knowledge as personal property to seeing knowledge as communal property is at the heart of knowledge management (leveraging the personal to help a broader set of individuals). To ensure that knowledge management is a true management discipline, we need to make sure that this is done systematically, routinely and in service of business strategy.

Our preferred definition, however, is that ‘knowledge management is the way you manage your team or your organisation, with due attention to the value of knowledge’. Knowledge management is therefore a managerial response to recognising the value of an asset. The managerial response – the processes, accountabilities and technologies applied – will vary depending on your organisational context. The unifying factor between these approaches is their focus on delivering value through knowledge, by making sure that people who need to take action have (or have access to) the knowledge to make that action effective.

Given that knowledge is intangible, knowledge management is not easy. However, modern businesses are becoming increasingly familiar with the practice of managing intangibles. Risk management, customer relations management, safety management and brand management are all recognised management approaches. Knowledge is not significantly less tangible or less measurable than risk, brand, reputation or safety, and the term ‘management’ suggests a healthy level of rigour and business focus. The value of a brand is enormous, and therefore brands need to be managed. The value of corporate knowledge is also enormous, so why should that value not also be managed? Brand, reputation, knowledge, customer base, etc., are intangible assets with great value to the organisation, and to leave these assets unmanaged would seem to be foolish in the extreme.

There is, in the literature and in current (2010) practice, much confusion between knowledge management and information management. You will find many definitions of knowledge management that refer only to information (for example the popular ‘knowledge management means getting the right information to the right people at the right time’) or to explicit content. In these cases, you could replace ‘knowledge management’ with ‘information management’ or ‘content management’ and the definition would still be valid. Knowledge management is more than information management and more than content management, and involves more than the provision of information or explicit content. Knowledge management needs to address the tacit as well as the explicit. It needs to cover access to experience and judgement as well as access to information.

Knowledge management models

In this section we look at some simple models for the management of knowledge and at some of the enabling factors that need to be in place to support these models. Some of the ideas and models introduced here will be built upon throughout the rest of the book.

Knowledge suppliers and users

Prusak’s definition presented in the previous section implies the existence of suppliers of knowledge (‘individuals’) and users of knowledge (‘others’), people in whose minds the knowledge is buried and people and teams who need access to that knowledge.

Knowledge is created through experience and through the reflection on experience in order to derive guidelines, rules, theories, heuristics and doctrines. Knowledge may be created by individuals, through reflecting on their own experience, or it may be created by teams reflecting on team experience. It may also be created by experts or communities of practice reflecting on the experience of many individuals and teams across an organisation. The individuals, teams and communities who do this reflecting can be considered as ‘knowledge suppliers’.

In business activity, knowledge is applied by individuals and teams. They can apply their own personal knowledge and experience, or they can look elsewhere for knowledge – to learn before they start, by seeking the knowledge of others. The more knowledgeable they are at the start of the activity or project, the more likely they are to avoid mistakes, repeat good practice, and avoid risk. These people are ‘knowledge users’.

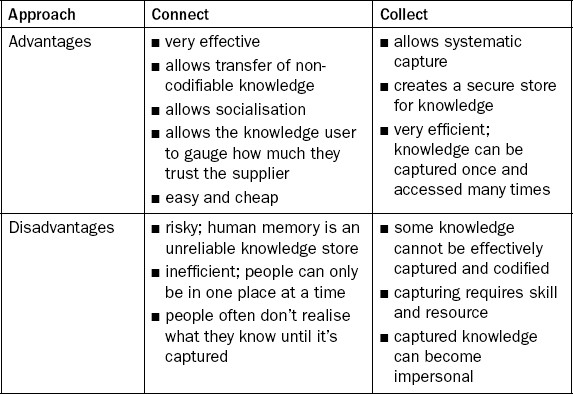

We have introduced the idea of tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. The knowledge can be transferred from the supplier to the user tacitly, through dialogue, or explicitly, through codifying the knowledge. Figure 1.2 shows these two approaches by looking at the two places where knowledge can be stored: in people’s heads or in codified form in some sort of ‘knowledge bank’ (Figure 1.2 is a redrafting of the SECI model of Nonaka and Takeuchi). These two stores can be connected in four ways:

![]() direct transfer of knowledge from person to person (communication);

direct transfer of knowledge from person to person (communication);

![]() transfer of knowledge from people to the ‘knowledge bank’ (knowledge capture);

transfer of knowledge from people to the ‘knowledge bank’ (knowledge capture);

![]() organisation of knowledge within the knowledge bank (organisation);

organisation of knowledge within the knowledge bank (organisation);

![]() transfer of knowledge from the ‘knowledge bank’ back to people (access and retrieval).

transfer of knowledge from the ‘knowledge bank’ back to people (access and retrieval).

Knowledge can therefore flow from supplier to user (from person to person, or team to team) in two ways.

The most direct (the upper left arrow on Figure 1.2) is through direct communication and dialogue. Face-to-face dialogue, or dialogue via an online communication system, is an extremely effective means of knowledge transfer. This method allows vast amounts of detailed knowledge to be transferred, and the context for that knowledge to be explored. It allows direct coaching, observation and demonstration. However, it is very localised. The transfer takes place in one place at a time, involving only the people in the conversation. For all its effectiveness as a transfer method, it is not efficient. For direct communication and dialogue to be the only knowledge transfer mechanism within an organisation would require a high level of travel and discussion, and may only be practical in a small team working from a single office where travelling is not an issue (for example a regional sales team that meets on a regular basis). This may be the only practical approach to the transfer of uncodifiable knowledge – that knowledge that cannot be written down (which Polyani would call ‘tacit’). However, it should not be the only mechanism of knowledge transfer, nor should knowledge be stored only as tacit knowledge in people’s heads. Using people’s memories as the primary place for storing knowledge is a very risky strategy. Memories are unreliable, people forget, misremember or post-rationalise. People leave the company, retire or join the competition. For example, what is the staff turnover in your team? Your division? Your company? How much knowledge is leaving your organisation in the heads of the departing people? There needs to be a more secure storage mechanism for crucial knowledge and a more efficient means of transfer than just dialogue.

The less direct flow of knowledge (the larger, lower right arrow on Figure 1.2) is through codification and capture of the knowledge, storage in some sort of ‘knowledge bank’ and retrieval of the knowledge when needed. The transfer is lower bandwidth than direct communication, as it is difficult to write down more than a fragment of what you know. No dialogue is possible and demonstrations are restricted to recorded demonstrations, e.g. using video files. Transfer of knowledge by this means is not very effective. However, the knowledge need only be captured once to be accessed and reused hundreds of times, so it is an efficient method of transferring knowledge widely. The knowledge is secure against memory loss or loss of personnel. This approach is ideal for codifiable knowledge with a wide user base. For example, the widespread transfer of basic cooking knowledge is best done through publishing cookery books. It is also ideal for knowledge that is used intermittently, such as knowledge of office moves or knowledge of major acquisitions. These events may not happen again for a few years, by which time the individuals involved will have forgotten the details of what happened, if it is not captured and stored.

These two approaches to knowledge transfer are sometimes called the connect approach (the smaller arrow), where knowledge is transferred by connecting people, and the collect approach (the larger arrow), where knowledge is transferred by collecting, storing, organising and retrieving it. Each method has advantages and disadvantages, as summarised in Table 1.1. Effective knowledge management strategies need to address both of these methods of knowledge transfer. Each has its place; each complements the other.

People, process, technology and governance

Systems for managing anything need to address the triple aspects of people, process and technology (see Figure 1.3). Each of these is a key enabler for any management system.

For example, a financial management system requires people (accountants, financial managers, commercial managers), processes (budgeting, accounting, financial auditing), and technology (SAP, Sage, Quicken, spreadsheets, calculators).

Similarly, a knowledge management system needs people to be assigned roles and responsibilities; processes for knowledge identification, capture, access and sharing; and technology for the storage, organisation and retrieval of knowledge.

The system of people, processes and technology will operate within a framework of corporate governance, which fosters a culture that supports the system. Financial management systems will work within a culture focused on the effective management of finances, where money is treated as company property rather than the property of the team or project, where wasting money is seen as a bad thing and where a project is not seen as being properly managed unless financial management is up to standard. This culture will be reinforced by a governance system, where the company rules for financial management are well defined and performance against these rules is audited and reported. If people don’t follow the rules, their future in the company is limited. Similarly, knowledge management systems will work in a culture where knowledge is seen to be important, where knowledge is treated as company property rather than the property of the team or project, where wasting knowledge is seen as a bad thing and where a project is not seen as being properly managed unless knowledge management is up to standard. This culture will be reinforced by a governance system, where the company rules for knowledge management are well defined and performance against these rules is measured and reported. If people don’t follow the rules, their future in the company is limited.

The ‘learning before, during and after’ model

The models presented in Figures 1.2 and 1.3 address the flow of knowledge from supplier to user and the components that need to be in place to allow this to happen. Figure 1.4 introduces one further model, which describes how knowledge management activities can fit within the cycle of business activity.

The management of knowledge, like the management of anything else, needs to be systematic rather than ad hoc, and needs to be tied into the business cycle. In any business, where business activities have a beginning and an end, knowledge can be addressed at three points. You can learn at the start of the activity, so that the activity begins from a state of complete knowledge (‘learning before’). You can learn during the activity, so that plans can be changed and adapted as new knowledge becomes available (‘learning during’). Finally, you can learn at the end of the activity, so that knowledge is captured for future use (‘learning after’). This model of ‘learn before, during and after’ was developed in BP during the 1990s, and we remember drawing the first diagram of this model in Shepperton, UK, in 1997. The ‘learn before, during and after’ cycle also appears to have been developed independently in several other organisations (Shell, for example, refer to it as ‘Ask/Learn/Share’).

However, there is more to the model than just the ‘learn before, during and after’ cycle. The knowledge generated from the project needs to be stored somewhere, in some sort of knowledge bank. Knowledge can be deposited in the bank at the end of the project and accessed from the bank at the start of the next project. Knowledge packaged and stored in the knowledge bank can be considered to be knowledge assets.

The final components of the framework are the people components. Communities of practice, communities of purpose or communities of interest (Chapter 4) need to be established to create and manage the knowledge assets. Knowledge roles (Chapter 6) need to be created in the business, to make sure that knowledge management is embedded in the business activity. Without knowledge roles, knowledge management becomes ‘everyone’s job’ and very quickly reverts to being nobody’s job.

This six-component model (learning before, learning during, learning after, building knowledge assets, building communities of practice and establishing business roles) is a robust model that creates value wherever it is applied.

The business need for knowledge management

This section looks at the business justification for knowledge management and where some of the value may lie. It also addresses the identification of the crucial knowledge that needs to be managed and looks at the lifecycle of knowledge within an organisation.

Business justification is crucial. If you can’t clearly articulate the need for knowledge management you should not be doing it. You shouldn’t be doing knowledge management only because you think it’s a cool, good or fashionable thing to do. You should be able to clearly outline the business reason for doing it. This section outlines two business reasons for managing knowledge: reducing the learning curve and bringing everybody up to the benchmark, both of which will have a positive effect on the bottom line.

Knowledge and performance

There is an old saying – ‘It’s easy when you know how.’

Any task is easy to perform, if you have the know-how. Knowledge management consists of making sure that the teams and individuals have the know-how they need to enable them to make effective decisions and so to improve their performance. Knowledge feeds performance and knowledge is also derived from performance. If your performance on a task or project is better than it was the previous time, then you have learned something. Your know-how has increased and that know-how should be identified, analysed, codified (if possible) and disseminated to other teams. The higher your level of knowledge, the higher your level of performance. You learn from performance and you perform by applying the knowledge you have learned. (The word ‘you’ in this paragraph can be singular, referring to an individual, or collective, referring to a project team or community of practice.) Performance and learning can form a closed loop.

The knowledge/performance loop shown in Figure 1.5 shows the close link between these two elements and it is fairly obvious from this link that knowledge management and performance management are also strongly linked. Knowledge management is far easier to apply in an organisation with good consistent performance metrics, a performance culture, performance measurement, reporting and target-setting, and internal benchmarking. In an organisation like this, the effects of increased knowledge will be obvious and the suppliers of knowledge (the higher performers) can be identified, as well as the customers for that knowledge (the lower performers, new recruits or people new in the role).

Where performance is less easy to measure, knowledge management can still be applied, but it will be more difficult to make it systematic and embedded in the business process and it will be considerably more difficult to measure the benefits.

Your knowledge management system and your performance management system should be aligned; they should operate on the same scale (cover the same areas of the company) and to the same frequency. Generally, the periodicity of target-setting and performance-measuring should match the periodicity of learning and review. If weekly sales targets are set, then learning should be reviewed on a weekly basis. If targets are set on a monthly basis, then they should be reviewed, and learning collected, on a monthly basis.

The learning curve

The concept of the learning curve is well established. The longer you do something and the more times you repeat something, the better you get at it. A team that works together on a regular basis will find that over time they get better, their sales figures go up, their bid success ratio rises and their market share increases.

Figure 1.6a represents a team that runs a programme of six activities. Over time they get better at these types of activity and the results improve. By the time they get to the fifth and sixth sales, marketing or bid project, they are working at their maximum capacity. The one thing that they have at the end of this curve, which they did not have at the beginning, is knowledge. They have gained know-how, experience, guidelines and heuristics for running this sort of activity.

If they manage their knowledge by concentrating on ‘learning during’ the programme and transferring the knowledge from one project to the next, they may be able to learn faster. This is shown diagrammatically by in the solid bars in Figure 1.6b. Here the overall value of the results from six activities has been increased by steepening the learning curve.

If they also ‘learn before’ the programme, by bringing in knowledge and experience from similar previous programmes, they don’t have to start at the bottom of the learning curve. Figure 1.6c shows further improvement in results by learning before the first activity and then continuing to learn through the sequence. What often happens, however, is that this focus on learning will also drive innovation, and improvements in maximum efficiency may result. The teams may exceed the maximum performance they otherwise would have achieved, as shown in Figure 1.6d, where overall improvements of about 20 per cent have been achieved.

Benchmarking

Another way to look at the value of knowledge management is to observe the transfer of best practices from one part of the business to another, as shown in Figure 1.7.

If you can measure and compare the performance of different teams in business units, you can identify the better performers and the poorer ones. For example, Figure 1.7a shows the performance results for six different teams. High bars equate to good performance, such as high sales, high market share or high win ratio.

Teams A and D are the best performers, with A setting the benchmark, and E and F are the worst. If all of these teams exchange knowledge and the poorer performers learn from the better performers, the overall performance should improve, as shown in Figure 1.7b. All of the teams have improved and C has set a new benchmark. Considerable value has been added to the organisation.

Internal benchmarking metrics can therefore be a powerful means of measuring the value of knowledge management and of identifying the knowledge suppliers and the knowledge users (in Figure 1.7a, teams A and D are primarily knowledge suppliers, and teams B, C, E and F are knowledge users, although to an extent all teams both supply and use knowledge).

Which knowledge?

The models shown in the previous two sections describe where the business value of knowledge lies, but not all knowledge is of equal value. Some knowledge will be crucial to your business and some will be largely irrelevant. Some knowledge drives your core competencies, while some can be conveniently outsourced. One key component of setting your knowledge management strategy within a business, or your knowledge management plan for a project, is to define which knowledge – which knowledge is needed, which knowledge needs to be acquired, which knowledge will be generated, which knowledge needs to be captured and codified, etc.

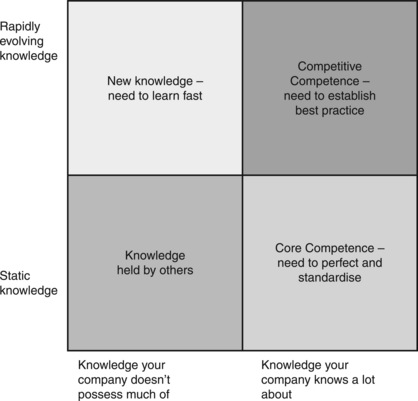

Figure 1.8 shows a framework for deciding which knowledge to address and how to manage it. You can start to divide knowledge topics into four areas if you look at two components: the level of in-house knowledge that currently exists and the level of in-house need for that knowledge.

![]() Where an important area of knowledge is new or rapidly evolving and the level of in-house knowledge is not yet very high, you are at the top of the learning curve and your focus should be on rapid learning.

Where an important area of knowledge is new or rapidly evolving and the level of in-house knowledge is not yet very high, you are at the top of the learning curve and your focus should be on rapid learning.

![]() Where an important area of knowledge is new or rapidly evolving and the level of in-house knowledge is high, you are looking at areas of competitive competence. You know a lot, in a new area, and your focus should be on development and implementation of best practices – on finding the best and most effective solutions and making sure people share these.

Where an important area of knowledge is new or rapidly evolving and the level of in-house knowledge is high, you are looking at areas of competitive competence. You know a lot, in a new area, and your focus should be on development and implementation of best practices – on finding the best and most effective solutions and making sure people share these.

![]() Where an important area of knowledge is fairly mature or static and the level of in-house knowledge is high, you are looking at areas of established knowledge and core competence and your focus should be on standardising your approach.

Where an important area of knowledge is fairly mature or static and the level of in-house knowledge is high, you are looking at areas of established knowledge and core competence and your focus should be on standardising your approach.

![]() Where an important area of knowledge is fairly mature or static and the level of in-house knowledge is low, this is generally an area you have outsourced, perhaps to an ad agency or a market research company. Here your focus should be sharing context with these companies, so they can bring the right knowledge to bear, and also on ensuring that they have KM in place to manage the knowledge on your behalf.

Where an important area of knowledge is fairly mature or static and the level of in-house knowledge is low, this is generally an area you have outsourced, perhaps to an ad agency or a market research company. Here your focus should be sharing context with these companies, so they can bring the right knowledge to bear, and also on ensuring that they have KM in place to manage the knowledge on your behalf.

An early step in development of the business knowledge management strategy or a project knowledge management plan is to identify the key knowledge areas and plot them on a matrix such as Figure 1.8. Critical knowledge for sales and marketing will be addressed in Chapter 2.

Approaches to knowledge management

The more widely you read around the topic of knowledge management, the more knowledge managers you meet and the more conferences you attend, the more you will come to realise that there are many approaches to managing knowledge. This section introduces some of these approaches, and makes the case for a holistic and systematic approach as described above.

The default approach

The default approach that many companies use is to keep knowledge in people’s heads and to manage the knowledge by managing the people. Knowledge is owned by the experts and the experienced staff. Knowledge is imported to businesses and projects by assigning experienced people as members of the project team. Knowledge is transferred from site to site by transferring staff and by using company experts who fly around the world from project to project, identifying and spreading good practices.

This is a very traditional model, but it has many major failings and cannot be considered to be knowledge management. Imagine you managing your finances in this way! Imagine if the only way to fund a project was to transfer a rich person into the business or to fly individual millionaires around the world to inject funds into the business or projects they liked!

The major drawbacks of this default ‘knowledge in the heads’ approach are as follows:

![]() Experienced people can only be on one project at a time.

Experienced people can only be on one project at a time.

![]() Knowledge cannot be transferred until people are available for transfer.

Knowledge cannot be transferred until people are available for transfer.

![]() Experts who fly in and fly out often do not gain a good appreciation of how things are done and where the good practices lie. In particular, teams in the business may hide their failings from the company experts in order to be seen in a good light.

Experts who fly in and fly out often do not gain a good appreciation of how things are done and where the good practices lie. In particular, teams in the business may hide their failings from the company experts in order to be seen in a good light.

![]() The burn-out potential for the experts is very high.

The burn-out potential for the experts is very high.

![]() Knowledge can become almost ‘fossilised’ in the heads of the experts, who can end up applying the solutions of yesterday to the problems of today.

Knowledge can become almost ‘fossilised’ in the heads of the experts, who can end up applying the solutions of yesterday to the problems of today.

![]() When the expert leaves, retires, has a heart attack or is recruited by the competition, the knowledge goes with them.

When the expert leaves, retires, has a heart attack or is recruited by the competition, the knowledge goes with them.

Unfortunately, for the experts and the experienced people, this can be an attractive model and was stereotypical behaviour for specialist bidders and marketers for many years. It can be very exciting travelling the world, with everyone wanting your assistance. It is like early Hollywood movie scenes with the US Cavalry riding over the horizon to save the wagon train at the last minute. Knowledge management, however, would make sure that the wagon train did not get into trouble in the first place. As one expert said recently, ‘If you could fly off to Russia and be a hero, or sit behind your desk and capture knowledge, what would you rather do?’

Partial approaches

There are many partial approaches to knowledge management, whereby some components of the model are applied and others omitted. These sometimes have partial success, but nothing like the success that might be delivered by a more consistent, systematic and holistic solution. Some of the common partial solutions are listed below:

![]() A technology-led approach – Here an organisation commonly builds or buys a ‘knowledge base’ or a ‘collaboration platform’ where explicit knowledge can be stored, searched and shared with other teams. Such technology can be a key component of a holistic solution and addresses the technology components of the capture, organise and retrieve boxes of Figure 1.3. However, unless you address the people and process technologies as well, the database will either remain empty, be sporadically filled only from selected activities or projects, or will fail to address the aspects of systematic reuse. Many organisations fall into the trap of applying a technology-led approach (possibly because it is relatively easy to buy and install a piece of technology), but find that the technology is unused. Technology is rarely the single barrier to knowledge management, and implementing technology alone is rarely sufficient. If technology were the barrier, you would see people in the organisation struggling to exchange knowledge with substandard technology such as telephones, Word documents and paper files. It is much more common to find the barrier is lack of culture, lack of process or lack of accountabilities.

A technology-led approach – Here an organisation commonly builds or buys a ‘knowledge base’ or a ‘collaboration platform’ where explicit knowledge can be stored, searched and shared with other teams. Such technology can be a key component of a holistic solution and addresses the technology components of the capture, organise and retrieve boxes of Figure 1.3. However, unless you address the people and process technologies as well, the database will either remain empty, be sporadically filled only from selected activities or projects, or will fail to address the aspects of systematic reuse. Many organisations fall into the trap of applying a technology-led approach (possibly because it is relatively easy to buy and install a piece of technology), but find that the technology is unused. Technology is rarely the single barrier to knowledge management, and implementing technology alone is rarely sufficient. If technology were the barrier, you would see people in the organisation struggling to exchange knowledge with substandard technology such as telephones, Word documents and paper files. It is much more common to find the barrier is lack of culture, lack of process or lack of accountabilities.

![]() An E2.0-led approach – This is a variant of the technology-led approach, whereby an organisation introduces a collaboration toolkit of workspaces, blogs, wikis and discussion forums. Again, these technologies are very powerful in supporting knowledge management, but they alone will not deliver knowledge management. Unfortunately, many companies roll them out and then expect KM to emerge spontaneously. It doesn’t, because the people, process and governance aspects have again been ignored.

An E2.0-led approach – This is a variant of the technology-led approach, whereby an organisation introduces a collaboration toolkit of workspaces, blogs, wikis and discussion forums. Again, these technologies are very powerful in supporting knowledge management, but they alone will not deliver knowledge management. Unfortunately, many companies roll them out and then expect KM to emerge spontaneously. It doesn’t, because the people, process and governance aspects have again been ignored.

![]() A community-led approach – A common partial approach is to implement communities of practice or communities of purpose (see Chapter 4) as the primary knowledge management solution. Knowledge is transferred primarily in the tacit realm, along the short connect arrow in Figure 1.2. Sometimes the communities also take ownership of explicit knowledge, so the longer collect arrow is also addressed, and if this happens, you certainly are developing a more complete knowledge management solution. However, unless the business teams and business projects are also involved in knowledge management, the ‘learn before, during and after’ cycle in Figure 1.4 never gets deployed and knowledge management therefore becomes decoupled from the cycles of business activity. Many companies introduce communities of practice as the ‘silver bullet’ – the only thing they need to manage knowledge – while in fact communities are only one dimension of a multidimensional solution. They are, however, a good place to start, and Mars (Chapter 9), Aon and others have had great success with KM strategies that start with communities and then broaden.

A community-led approach – A common partial approach is to implement communities of practice or communities of purpose (see Chapter 4) as the primary knowledge management solution. Knowledge is transferred primarily in the tacit realm, along the short connect arrow in Figure 1.2. Sometimes the communities also take ownership of explicit knowledge, so the longer collect arrow is also addressed, and if this happens, you certainly are developing a more complete knowledge management solution. However, unless the business teams and business projects are also involved in knowledge management, the ‘learn before, during and after’ cycle in Figure 1.4 never gets deployed and knowledge management therefore becomes decoupled from the cycles of business activity. Many companies introduce communities of practice as the ‘silver bullet’ – the only thing they need to manage knowledge – while in fact communities are only one dimension of a multidimensional solution. They are, however, a good place to start, and Mars (Chapter 9), Aon and others have had great success with KM strategies that start with communities and then broaden.

![]() A content-led approach – Here an organisation introduces document management or content management as its approach to knowledge management. It assumes that the greater part of knowledge is held in explicit form in documents and that if these documents can be organised, stored, searched and retrieved (perhaps using techniques such as data mining, text summarisation and natural-language searching), knowledge will be shared. Unfortunately, this is an extremely ineffective way of managing knowledge. Many documents contain far more data and information than knowledge, and unless there is a systematic owned process for knowledge identification and capture, most of the knowledge will never make it into document form in the first place. In addition, unless there is a systematic owned process for knowledge validation, distillation and organisation, knowledge will become diluted and irretrievable in a sea of irrelevant documentation. Finally, this approach deals with explicit knowledge and will not address those components of knowledge that have to remain tacit because they are uncodifiable.

A content-led approach – Here an organisation introduces document management or content management as its approach to knowledge management. It assumes that the greater part of knowledge is held in explicit form in documents and that if these documents can be organised, stored, searched and retrieved (perhaps using techniques such as data mining, text summarisation and natural-language searching), knowledge will be shared. Unfortunately, this is an extremely ineffective way of managing knowledge. Many documents contain far more data and information than knowledge, and unless there is a systematic owned process for knowledge identification and capture, most of the knowledge will never make it into document form in the first place. In addition, unless there is a systematic owned process for knowledge validation, distillation and organisation, knowledge will become diluted and irretrievable in a sea of irrelevant documentation. Finally, this approach deals with explicit knowledge and will not address those components of knowledge that have to remain tacit because they are uncodifiable.

The holistic approach

The approach to knowledge management advocated in this book is a holistic approach, which addresses all of the dimensions. The models shown in Figures 1.2-1.4 are combined into a system that addresses:

![]() tacit knowledge (in people’s heads) and explicit knowledge (in the knowledge bank);

tacit knowledge (in people’s heads) and explicit knowledge (in the knowledge bank);

![]() knowledge communication, capture, storage and retrieval;

knowledge communication, capture, storage and retrieval;

![]() people, process, technology and cultural aspects;

people, process, technology and cultural aspects;

The rest of this book will look at how this system can be applied to sales and marketing.

Cultural issues

We previously discussed how knowledge management requires a profound shift in individual and corporate attitudes to knowledge. In Western society, knowledge is seen as an individual attribute. At school, children are tested on what they know and any attempt to access the knowledge of others is seen as cheating. In professional life, people often feel a sense of pride in their own skills, knowledge and achievements, and sometimes would rather solve a problem themselves, just for the challenge, than seek an existing solution. The individual’s knowledge and experience can also be felt to be a personal asset and a hedge against being made redundant, replaced or outsourced.

When people feel this way, there can be many cultural barriers to knowledge management. These include the following:

![]() knowledge is power: ‘if I tell you what I know, I lose some of my personal power’;

knowledge is power: ‘if I tell you what I know, I lose some of my personal power’;

![]() not invented here: ‘your knowledge is not as trustworthy as mine’;

not invented here: ‘your knowledge is not as trustworthy as mine’;

![]() drive to create: ‘it’s more fun finding the answer for myself, than using someone else’s answer’;

drive to create: ‘it’s more fun finding the answer for myself, than using someone else’s answer’;

![]() fear of exposure: ‘I am not going to share my failures with you, it might make me look bad’;

fear of exposure: ‘I am not going to share my failures with you, it might make me look bad’;

![]() fear of exposure (2): ‘I am not going to ask for help and advice, it makes me look as if I don’t know what I am doing’;

fear of exposure (2): ‘I am not going to ask for help and advice, it makes me look as if I don’t know what I am doing’;

![]() not my job: ‘I am paid for delivering results, not for sharing results with others’;

not my job: ‘I am paid for delivering results, not for sharing results with others’;

![]() not my job (2): ‘KM is not in my KPIs (key performance indicators, or key objectives), and not in my incentives. Why should I bother?’

not my job (2): ‘KM is not in my KPIs (key performance indicators, or key objectives), and not in my incentives. Why should I bother?’

Any organisation that sees the business value in knowledge management (i.e. reducing the learning curve, bringing everyone up to the best performance standard, as discussed earlier), needs to address these cultural issues. A new culture needs to be fostered, as follows:

![]() shared knowledge is greater power: ‘if we share what we know, we will meet our individual and strategic targets’;

shared knowledge is greater power: ‘if we share what we know, we will meet our individual and strategic targets’;

![]() invented here is not good enough: ‘we know we don’t know everything, and will look around for additional knowledge before every task’;

invented here is not good enough: ‘we know we don’t know everything, and will look around for additional knowledge before every task’;

![]() drive to perform: ‘it may be more fun to create the solution, but if a better solution exists, we will use it’ (saving time by applying existing solutions creates time for real innovation);

drive to perform: ‘it may be more fun to create the solution, but if a better solution exists, we will use it’ (saving time by applying existing solutions creates time for real innovation);

![]() fear of underperforming: ‘I am going to ask for help and advice because I want to make my job as easy and safe as possible’;

fear of underperforming: ‘I am going to ask for help and advice because I want to make my job as easy and safe as possible’;

![]() fear of underperforming (2): ‘if something went wrong on my project, I am going to make sure it never happens to any future projects’;

fear of underperforming (2): ‘if something went wrong on my project, I am going to make sure it never happens to any future projects’;

![]() it’s my job: ‘I am paid for delivering results, and that includes KM results’;

it’s my job: ‘I am paid for delivering results, and that includes KM results’;

![]() it’s my job (2): ‘KM is a prime enabler to delivering my KPIs, and thus my incentives. It’s part of the job’.

it’s my job (2): ‘KM is a prime enabler to delivering my KPIs, and thus my incentives. It’s part of the job’.

The more a team is driven by performance (their own team performance as well as the organisational performance) and empowered to seek solutions, the more readily they will embrace knowledge management as an aid to performance. Managers can reinforce this by encouraging and rewarding knowledge-seeking and knowledge-sharing, by setting the expectation that every team will seek to improve on the best of past performance, by empowering teams to seek the best solutions from across the organisation (and outside) and by minimising the effects of any internal competition between teams, projects and business units.

These thoughts are expanded further in Chapter 7, which covers culture and governance.

1.Milton, Nick (2004) Knowledge Management for Teams and Projects. Oxford: Chandos Publishing.

2.Young, Tom (2009) Knowledge Management for Services, Operations and Manufacturing. Oxford: Chandos Publishing.

3.Senge, Peter M. (2004) Conference Proceedings of KM Asia, Singapore, 2–4 November.

4.Polanyi, Michael (1966) The Tacit Dimension. First published Doubleday & Co. Reprinted Peter Smith, Gloucester, MA, 1983. Chapter 1: ‘Tacit Knowing’.

5.Nonaka, Ikujiro and Takeuchi, Hirotaka (1995) The Knowledge Creating Company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 284.