Culture and governance

The issue of culture in knowledge management is key. Introducing knowledge management involves more than introducing the processes, technologies and roles mentioned in the previous chapters. It also involves introducing a new culture and introducing the governance system that sustains that culture. The culture change involved with introducing knowledge management is a profound shift from the individual to the collective ownership of knowledge:

![]() from ‘knowledge is mine’ to ‘knowledge is ours’;

from ‘knowledge is mine’ to ‘knowledge is ours’;

![]() from ‘knowledge is owned’ to ‘knowledge is shared’;

from ‘knowledge is owned’ to ‘knowledge is shared’;

![]() from ‘knowledge is personal property’ to ‘knowledge is collective/ community property’;

from ‘knowledge is personal property’ to ‘knowledge is collective/ community property’;

![]() from ‘knowledge is personal advantage’ to ‘knowledge is company advantage’;

from ‘knowledge is personal advantage’ to ‘knowledge is company advantage’;

![]() from ‘knowledge is personal’ to ‘knowledge is interpersonal’;

from ‘knowledge is personal’ to ‘knowledge is interpersonal’;

![]() from ‘I defend what I know’ to ‘I am open to better knowledge’;

from ‘I defend what I know’ to ‘I am open to better knowledge’;

![]() from ‘not invented here (i.e. by me)’ to ‘invented in my community’;

from ‘not invented here (i.e. by me)’ to ‘invented in my community’;

![]() from ‘new knowledge competes with my personal knowledge’ to ‘new knowledge improves my personal knowledge’;

from ‘new knowledge competes with my personal knowledge’ to ‘new knowledge improves my personal knowledge’;

![]() from ‘other people’s knowledge is a threat to me’ to ‘our shared knowledge helps me’;

from ‘other people’s knowledge is a threat to me’ to ‘our shared knowledge helps me’;

![]() from ‘admitting I don’t know is weakness’ to ‘admitting I don’t know is the first step to learning’.

from ‘admitting I don’t know is weakness’ to ‘admitting I don’t know is the first step to learning’.

That shift from ‘I know’ to ‘we know’ and from ‘knowledge is mine’ to ‘knowledge is ours’ is a huge one and counter-cultural to many. People often attribute their success in an organisation and the salary and position that come from the success as due to their personal knowledge. To be asked to share their personal knowledge feels like being asked to relinquish power, rewards and security. People ask, ‘What’s in it for me?’

Chapter 10, the case study from the Ordnance Survey, describes some of the cultural barriers that mitigate against the flow of knowledge, including management and leadership, a lack of trust due to ‘a blame culture’ and the lack of defined boundaries between roles and responsibilities. We explore some of these barriers and influences below.

Knowledge management, target-setting and incentives

The conflict between personal rewards and security on the one hand and the organisational benefits of knowledge-sharing on the other is most obvious when it comes to target-setting and incentives. This is particularly clear in sales, where traditionally sales reps are given individual targets with a strong element of performance-related incentives. If they meet and exceed their targets, they can be highly rewarded, as well as recognised in various ‘sales rep of the year’ awards. Taking time out to share their tips and hints and knowledge with others not only distracts them from meeting their targets, but also potentially gives away some competitive benefit to people competing for those same targets.

In a sales team, it pays to think very carefully about target-setting. One sales manager we spoke to takes a counterintuitive approach to this in a bid to improve team knowledge-sharing. She assigns a team target for her team, for which the whole team is accountable. Then she assigns individual targets, set within the context of the team target, that are equal for every rep, regardless of their experience. So the most experienced sales representative gets the same target as the least experienced. This, she feels, is the fairest way to assign targets and avoid putting the whole burden on the experienced people while letting the juniors off lightly. Once the experienced staff have delivered their targets, they go on to help their less experienced colleagues, transferring knowledge in the process and helping to build a team spirit. All of the public praise and all of the public recognition is for the team target and none for the individual target. For this manager, there is no ‘sales rep of the year’.

The role of the manager in setting the culture

We can see in the example above the key role that the manager plays in setting the sharing culture within the team. The manager needs to reinforce this sharing culture by setting expectations and by managing the conversations.

Where there are recognition and accolades for individual performance, as soon as that happens, the manager has to move the conversation on to how the team can duplicate and apply these successes elsewhere. ‘There is never any bitterness about celebrating someone else’s success,’ one manager told us. ‘The team just want to know "Great, how did you do it and how can we copy it?" And if a person does succeed, they are the first to say "and here is how you can apply it in your area".’

The manager has to promote the behaviour of sharing success and best practice to help one another. There may be natural reluctance to sharing success and best practice; people don’t want to come across as boasting or maybe they don’t recognise the value of what they know, and the manager has to be careful to foster and encourage the correct behaviours. Sharing success has to be voluntary, but the manager can coach individuals to share openly and can set time in team meetings for sharing success.

The manager has to promote the behaviour of sharing the challenges as well. If one of the sales team has been having trouble meeting their targets, which will be apparent when the sales figures are shared, the manager should always ask for the team input and ask the team to share their knowledge of what they think the situation might need.

The quote below shows how this sort of manager attention can change team culture:

We have people who like to win and that is the key. When I first took on the team, they used to compete against one another. Now they compete only to increase the total results. How did I turn around the culture? I steered them in terms of the team results. I brought it up in the appraisals and also during all the other usual conversations in the team.

Dealing with inter-team competition

Of course this approach to team target-setting only develops a culture of knowledge-sharing within the team. Sales staff are naturally competitive people; they like to be winners and they like to compete. The first step is to build team collaboration, so that instead of having winners and losers within the team, the whole team become winners. However, they will still at this point want someone else to compete against. One sales manager said to us, ‘We build a sense of team success. We talk about the team target and then the first thing they want to know is whether we are leading the way in Canada (i.e. beating the other teams).’ So competition has been displaced from the team and replaced with inter-team competition.

However, for knowledge management to deliver its full potential, we need to look at knowledge-sharing not just within teams, but also between teams. How can we do this, when the teams perceive themselves to be rivals?

We do this by introducing structures that cross-cut the team structure. The communities of practice, communities of purpose and communities of interest all allow people to join something with membership from many teams. A sales representative in France could join a community of purpose on ‘selling to major supermarket chains’ and find herself at a workshop or knowledge exchange, working together with her counterparts in Australia and Mexico. Suddenly these people are not rivals, but allies. Communities are one of the most effective ways of introducing cross-team and cross-region sharing.

When it comes to identifying and sharing best practices, the central knowledge management team can play a role. Although a highly successful sales manager may not want to directly divulge his or her secrets to a rival sales manager, they might be perfectly happy to conduct an interview with the knowledge management team, even knowing that what they share with the knowledge management team will also be shared with the other sales departments. The difference of course is that this is two-way sharing; they will share, but they will receive in return. We have had great success gathering knowledge from sales managers and sales teams in this way.

Dealing with ‘not invented here’

The matter of competition between team members and between teams is much less of an issue for bids teams and marketing teams than it is for sales. For marketing and bidding, the biggest barrier tends to be ‘not invented here’, rather than internal competition.

‘Not invented here’ is one of the most difficult barriers to overcome in knowledge management. It is seen in teams who prefer to create their own solutions, rather than reusing the knowledge and the solutions of others. It is a common barrier in very creative teams or in teams where they are using their collective experience to create a product. In these cases, people feel far more secure or far more creatively satisfied if they create the product purely from their own experience. Even if another team has done something very similar, they still feel more secure in starting from a blank sheet of paper. Basically, ‘not invented here’ is often a symptom of an unwillingness to learn and there is absolutely no point in creating the best knowledge-sharing system if your organisation has a learning problem.

There are various ways of discouraging ‘not invented here’ or subtly encouraging the reuse of knowledge, but if you are looking for a lasting and sustained culture change, ultimately ‘not invented here’ has to become unacceptable behaviour.

One way to address this is to refuse to approve any marketing campaign or bid document that has been ‘only invented here’. The regional marketing director could make it clear that he or she will not approve a campaign that doesn’t build on knowledge and material from successful campaigns elsewhere in the world. The bid director could stress that he or she will not sign off a bid document if there has been no peer assist with other bid teams to build on their knowledge and experience. At the same time, of course, you have to build the communities of practice and the knowledge libraries that make it easy to find what others have done and to reuse it.

Another leader refused to accept ‘only invented here’ by introducing what he calls ‘no single-source solutions’. It is a stated point of principle within his part of the organisation to have no single-source solutions – solutions that have been worked up by one person with no input from other parts of the business. Single-source solutions represent ‘only invented here’ and by refusing to accept these, he gives the message that solutions have to be based on multiple inputs and external knowledge.

Knowledge management expectations

In the previous section, we saw examples of regional marketing managers or bid directors making their expectations for knowledge management very clear. Clear expectations are vital if the knowledge management culture is to be introduced, and everybody in sales, bidding and marketing needs to know what is expected of them in knowledge management terms. This expectation has to come down from senior management. They need to write these expectations down and keep reinforcing them by what they say and do. They also need to make sure these expectations do not get weakened by or conflict with other company structures and expectations, such as the incentive scheme (see above about setting team targets rather than individual targets).

One clear way to define expectations is to define an in-house standard for knowledge management. What does this mean in practice? What is an acceptable level of knowledge management activity? Does every bid project need to hold a retrospect, or only the big ones? Are peer assists a mandatory requirement for marketing campaigns, or optional? Does every sales representative need to update the CRM database after every sales call? You need to sit down with senior management and decide what the corporate KM standard is going to be.

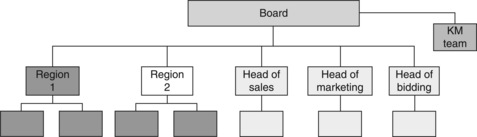

Along with clarity on standards comes clarity on accountability. By accountability we mean, whose job is it to ensure learning and sharing? Whose responsibility is it to make sure that the knowledge base is updated? Who are the knowledge owners? Senior management will need to set up one or more chains of accountability, so that everyone in the organisation knows what is expected of them. We say ‘one or more’ chains – in many organisations there will be three chains of accountability, as shown in Figure 7.1.

There will certainly be a chain of accountability in the line organisation (Region 1 and Region 2 in Figure 7.1) – the organisation of business units that ‘do the work’. Here the accountability will be about capturing new knowledge and reusing existing knowledge. For example, the head of European marketing may be accountable for ensuring that the European marketing division captures and shares its knowledge and uses knowledge from elsewhere in the world. He or she will devolve this accountability down to the country managers, who will in turn pass this down to the marketing teams.

In a matrix organisation, there may also be a chain of accountability in the functional or support departments. Here the accountability is likely to cover the ownership, maintenance and deployment of the company knowledge base and will include accountabilities for knowledge ownership and community leadership. The head of sales, for example, will be accountable for making sure that the company’s sales processes are managed and updated and will ensure that the individual knowledge owners and community leaders are doing their jobs properly.

Finally, there will be a set of accountabilities for the knowledge management support team. These will include accountability for maintaining the knowledge management system and for monitoring and measuring its use.

Reinforcement

Knowledge management needs to be reinforced. People who perform well in knowledge management need to be recognised and those who do not conform to their accountabilities or to the corporate expectations may need to experience some sort of sanction.

Bob Buckman, the CEO of Buckman Laboratories, was very good at this. The KM team measured the use of the knowledge management tools by the sales and support staff at Buckman Laboratories and reported this to the CEO on a regular basis. Staff who were particularly good at sharing and reusing knowledge were rewarded with new laptops and with other non-monetary rewards. Staff who were not using the system would receive an e-mail that might say, ‘Dear Associate, You have not been sharing knowledge. How may I help you?’ And those associates who still refused to comply with the knowledge management expectations might receive an e-mail that says, ‘If you are not willing to contribute or participate, then you should understand that the many opportunities open to you in the past will no longer be available.’1

Organisations that are serious about knowledge management have to take an approach similar to Bob Buckman’s. He reinforced positive behaviours and sanctioned negative behaviours. People found that their personal involvement in knowledge management impacted their prospects and as a result Buckman Laboratories had a well-embedded knowledge management culture.

1.Quoted in Mohr, J.J., Sengupta, S. and Slater, S. (2009) Marketing of High-Technology Products and Innovations. Published by Jakki Mohr. ISBN 0136049966.