Communities in sales and marketing

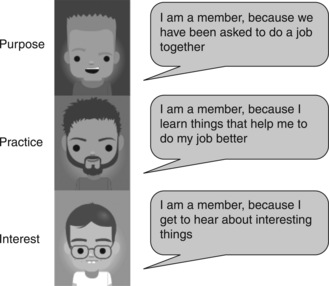

Communities have a huge role to play in knowledge management in the sales and marketing areas. As we describe this role, we will discuss three different types of communities: communities of practice, communities of purpose and communities of interest.

![]() Communities of practice are the knowledge management standard. A community of practice is, as you might expect, a community of practitioners – practitioners within a single area or discipline. They may be a community of sales people, a community of marketers, a technical support community or a bid community. Their conversation is about practice – about selling, about marketing, about bidding – and the purpose of the community is primarily to help each other to improve their practice, by using the tacit knowledge of the community as a shared resource. By sharing what they know, they become better sellers, better marketers, etc. The community does not deliver anything collectively to their host company; all the output they create is for the benefit of the community members. Communities of practice generally are voluntary and often have little or no funding from the host company.

Communities of practice are the knowledge management standard. A community of practice is, as you might expect, a community of practitioners – practitioners within a single area or discipline. They may be a community of sales people, a community of marketers, a technical support community or a bid community. Their conversation is about practice – about selling, about marketing, about bidding – and the purpose of the community is primarily to help each other to improve their practice, by using the tacit knowledge of the community as a shared resource. By sharing what they know, they become better sellers, better marketers, etc. The community does not deliver anything collectively to their host company; all the output they create is for the benefit of the community members. Communities of practice generally are voluntary and often have little or no funding from the host company.

![]() Communities of purpose are different. They are funded by a company or by a host organisation and, in return, commit to deliverables. This type of community will have an identified set of members, rather than being totally voluntary. They will have joint objectives. They often act as a virtual team. Their conversation is about practice, so they are different from a multi-discipline team, but in many ways they behave like a team. An example of these communities of purpose is the global practice groups at Mars, described in Chapter 9.

Communities of purpose are different. They are funded by a company or by a host organisation and, in return, commit to deliverables. This type of community will have an identified set of members, rather than being totally voluntary. They will have joint objectives. They often act as a virtual team. Their conversation is about practice, so they are different from a multi-discipline team, but in many ways they behave like a team. An example of these communities of purpose is the global practice groups at Mars, described in Chapter 9.

![]() Communities of interest are different again. These consist of people who are interested in a particular topic, but it is not their area of practice. Their purpose is to receive and share information, but this information is not about their practice area. Membership is entirely voluntary. In the sales and marketing world, these communities might be external customer communities or internal product communities for sharing product information along the supply chain. There has been a lot of interest recently in building communities of interest among the customer base using social networking software, as a way of building brand loyalty.

Communities of interest are different again. These consist of people who are interested in a particular topic, but it is not their area of practice. Their purpose is to receive and share information, but this information is not about their practice area. Membership is entirely voluntary. In the sales and marketing world, these communities might be external customer communities or internal product communities for sharing product information along the supply chain. There has been a lot of interest recently in building communities of interest among the customer base using social networking software, as a way of building brand loyalty.

We will look at these three types of community in more detail below.

Communities of practice

Communities of practice are peer networks of practitioners within an organisation that help each other perform better by sharing lessons and knowledge. Many large companies have set up dozens of communities of practice, some of which may have over a thousand members. Communities generally have a facilitator or moderator and may sometimes have a sophisticated governance system. Community members exchange knowledge in two ways. They can capture, create and/or share process documents or they can use discussion forums to ask each other for help and advice.

For a community of practice to operate effectively as a mechanism for sharing knowledge, it needs the following enablers:

A way to ask questions and give answers

The primary way for community members to access the tacit knowledge of the organisation is through asking questions. Any community member facing a problem where they lack complete knowledge should have a means of asking the community for help and of receiving answers. In a co-located community, this can be done in regular face-to-face meetings. Communities of practice in dispersed or multinational businesses cannot meet regularly face to face. They need some virtual means of raising questions and receiving answers.

There are many web-based or e-mail-based discussion tools or question and answer forum tools that allow just this facility, and these are proven and popular tools for sharing knowledge within communities. Buckman Laboratories, for example, operate several global communities of practice, each with its own online Q&A forum, so that customer-facing sales agents anywhere in the world can access lessons from their peers by sending an e-mail asking for lessons and advice. An e-mail will be forwarded to all members of the community and anybody who can share their learning will reply. Replies are collated as a ‘threaded discussion’ on a community forum and community members can read this discussion and their own comments and learn themselves. Social networking software such as Facebook, Twitter, Yammer and SalesForce Chatter also allows community members to ask each other for help and advice.

This sort of online interaction has historically worked better for marketing than for sales, as marketers are more likely to be sitting behind a desk and in front of a screen. However, the increase in power and connectivity of handheld tools and smartphones now means that sales people can join in the online conversation from anywhere they happen to be. This is discussed further in Chapter 6.

A sense of identity

The members of a community are happy to share lessons with each other because they feel a sense of identity with each other. They see each other as fellow practitioners, sharing the same challenges, facing the same issues and having valuable learning to share. People will feel ‘at home’ in a community if they identify with the community topic. Therefore the most effective communities tend to be the ones that deal with people’s core tasks. When you get a group of sales reps in a bar, they tend to talk sales all night. This is the sort of interest, energy and identification with the topic that will really hold a community together. The sense of identity can be strengthened through a face-to-face community launch meeting and then regular face-to-face meetings of the community and by focusing the community on core jobs. So if your sales force is split by product category, such as sellers of cosmetics, sellers of health foods, sellers of medicines, it makes sense to have three communities of practice: Cosmetics Sales, Health Sales, Medical Sales. If, however, the same sales team is responsible for all three categories of product, just have a single sales community. As described in Chapter 9, the marketing communities at Mars are based on global brands and on issues such as marketing petcare products in the developing world, while the sales communities are cross-product-segment communities related to sales, such as selling through distributors or selling to global supermarket chains.

An energetic coordinator

The community of practice needs a defined coordinator.1 This is the person who is accountable for the smooth operation of the community. Some of the responsibilities of the coordinator include:

![]() managing the community discussions (online and face to face);

managing the community discussions (online and face to face);

![]() making sure agreed community behaviours are followed;

making sure agreed community behaviours are followed;

![]() setting up the community meetings;

setting up the community meetings;

![]() working with the community core team;

working with the community core team;

![]() liaising with subject matter experts and process owners;

liaising with subject matter experts and process owners;

![]() watching for problems where knowledge-sharing is not happening;

watching for problems where knowledge-sharing is not happening;

![]() maintaining the membership list;

maintaining the membership list;

![]() representing the community to management;

representing the community to management;

![]() managing the lifecycle of the community;

managing the lifecycle of the community;

![]() keeping energy levels high amongst participants, to ensure active participation.

keeping energy levels high amongst participants, to ensure active participation.

The most important attributes for the community coordinator are passion and energy. The coordinator of the community acts as the dynamo for the community, keeping energy levels high and positive. The community coordinator needs to be an insider; they need to be a member of the organisation, they need to be well known and well respected and they need to be a practitioner in the topic. They have to understand the jargon and the language and they have to know the key players. The community leaders can be appointed (as in Buckman Laboratories), they can be nominated by the community (as in Mars) or they can emerge as the natural leader based on their passion and energy. They can be called coordinators or facilitators or leaders or minders – whatever terminology is acceptable to the community. In a small community, the coordinator role may be part-time. In a larger community, say of more than 500 members, the coordinator role should be full-time. This is especially true if the community knowledge is of strategic value.

A core team

Sometimes a community facilitator may need a core team to help them run the community. In Mars, this is represented by a steering team of senior, experienced associates who set the agenda for the coming year and control the centrally focused activities. In other communities, the core team is a set of self-appointed practitioners who voluntarily take a hand in managing the community business.

Critical mass

Communities of practice need a certain amount of interaction in order to remain in the consciousness of the community members and therefore to be a source of learning that people naturally turn to. They can suffer from ‘out of sight, out of mind’, and a community that is too small or too preoccupied to be sufficiently active will begin to lose its sense of identity and people will forget it is there. The community coordinator therefore needs to build membership and grow the community as fast as possible after launch to keep the momentum going and to get to critical mass. This will require a combination of internal marketing, advertising, awareness-raising and direct invitation to people who might be interested. This is likely to take a considerable portion of the community coordinator’s time in the first few months after launch. Each potential new member needs to be welcomed into the community, introduced to the terms of reference and encouraged to take part in knowledge-sharing, thus building mass one member at a time. The size of the critical mass varies depending on the intensity of the learning, the passion of the individuals and how diverse they are culturally and geographically. For a co-located community of passionate experts working in a new field, the critical mass may be a dozen people. For a global community working in an established field, exchanging knowledge through e-mail and online, the critical mass may be several hundred people. In Chapter 9, Mars describe how they moved from a model of many small communities to one of a few large communities in order to build critical mass more quickly.

A way to find each other

Communities must be visible. Staff must be able to find relevant communities, they must be able to join them easily and they must be able to see who else is a community member. There should ideally be, in the organisation, some index or ‘yellow pages’ for the communities.

A community knowledge library

A community working on common processes and common topics needs their own knowledge library. This may be a community space within the corporate knowledge library discussed in Chapter 6, while many large communities will have their own portal. The InTouchSupport.com system in Schlumberger, for example, cost $160 million to develop a knowledge base to store and share knowledge on technical solutions for the technical service community. Because technology support is Schlumberger’s main business, the company felt that this investment was worthwhile. By cutting 95 per cent from the time it takes to answer a technical question, it adds a claimed annual value of $200 million, through giving Schlumberger staff the ability to solve technical problems very rapidly in a business where time is money.

Smaller communities may develop their own knowledge library, perhaps on a SharePoint site or as a community wiki. A community blog is often very useful as well to notify the community of any new lessons, new knowledge or updated processes in the library.

A social network

Communities of practice are one particular type of social network – a social network with the purpose of collective learning. The members of a community are happy to share lessons and knowledge with each other because they feel a sense of identity with each other and they are even happier to share their lessons with community members whom they know personally and feel a social connection with. Much work has been done in the field of knowledge management on building social networks and on the concept of social network analysis. This involves mapping out the social links and the interactions within a community in order to assess the level of connectivity of the individuals. The community coordinator should be using any means possible to improve social connectivity, including the use of social software where appropriate. Social connectivity forms the groundwork for developing trust within the community, and trust is an essential ingredient if knowledge is to be shared and reused. However, assured and systematic learning within the community needs to transcend the social networks and the community needs to develop processes and approaches for accessing the knowledge of people they don’t know and have never met. Approaches such as the discussion forums described above allow knowledge-sharing to take place within an entire community, regardless of how socially connected the individuals may be.

A level of autonomy

In allowing communities of practice to exist and operate, the organisation is accepting that much of the knowledge lies with the practitioners and that unwritten lessons can effectively be shared between the practitioners. The organisation must therefore give the practitioners enough autonomy to act on the lessons they receive. They should be empowered to reuse lessons, best practices and process improvements that have been validated by the community, without necessarily getting their line manager to revalidate them every time. This does not mean that all decision-making is delegated to community members, but it means that line management can delegate a certain level of technical assurance to the communities. Disempowered communities rapidly become cynical and disaffected, which can become a bigger problem for management than having no communities at all.

External linkage

Marketing communities, in particular, may benefit from including external people, such as the marketing agencies, in order to be able to access their knowledge and experience. However, care must be taken when including more than one agency, particularly if they are in competition. They may not want to be as free and open with their knowledge if their competitors are listening in, or they may start to compete with each other, ‘selling’ their knowledge rather than sharing it objectively.

Communities of purpose

A community of purpose is a community of people from around the organisation, working within a single discipline. It differs from a community of practice in that these people are assigned to the community and the community of purpose is given (or sets itself) specific tasks and specific deliverables. The primary reason for a community of purpose is to develop organisational capacity and to deliver organisational results, in contrast with the community of practice where the purpose is to develop individual capacity and help individuals produce better results. Communities of purpose go under many names; Mars and Aon call them Global Practice Groups, BP calls them Delivery Networks, other organisations may call them expert communities or networks of excellence. The following is the Mars definition of Global Practice Groups (see Chapter 9):

(Communities of purpose are) small groups of senior associates who are charged with delivering a step change in performance in an area of strategic importance to the company.

For a community of purpose to operate effectively as a mechanism for sharing knowledge, it needs the following enablers:

A business sponsor

The community of purpose needs an active sponsor at a high level within the organisation (in Mars, at the level of the Presidents Group), who has accountability for success of the particular discipline. For example, the head of sales would be the sponsor for any sales communities of purpose, the head of marketing would be the sponsor for any marketing communities of purpose, and so on. The sponsor is responsible for ensuring the community has what it needs to succeed, in terms of resource, space and time to operate, and empowerment. Through discussion with the core team, the sponsor will agree what the community goals should be and how they will be measured and will sign off on the community performance contract. The sponsor should also help set the leadership style, if communities are a new way of working, and should ensure that the results are visible across the business.

A leader and a delivery structure

The community of purpose needs a leader. Whereas a community of practice can operate with a facilitator, a community of purpose actually needs to define a leader who can take accountability for effective running of the community and for effective delivery of the community performance contract. The leader will be appointed by the sponsor and will almost certainly be a senior and respected player within the discipline, perhaps one of the company experts. The leader provides overall leadership and direction for the community, organises and runs community meetings and works together with the community sponsor to develop community objectives and to agree and draft the community performance contract.

The leader will also work with the core community members to develop plans to deliver these objectives and will coordinate and follow up the activities of the community to ensure that the community delivers its goals. He or she will maintain activity and energy within the community (Mars describe the leader as the ‘Energiser Bunny’ of the group in Chapter 9) and will set the working culture and open style of community working, ensuring that there is reward and recognition of the community members and that feedback is given on any value they have delivered.

A performance contract with well-defined deliverables

We have mentioned performance contracts a couple of times, and holding a performance contract differentiates a community of purpose from the community of practice. The performance contract is an agreement between the sponsor and the community that defines what the community aims to deliver in return for funding. This delivery is generally expressed in terms of business deliverables, such as ‘achieve global sales growth of five per cent by building and sharing best practices in online marketing’, plus a number of steps to achieve that deliverable. The performance contract should ideally be built ‘bottom up’ by the community itself, then agreed (or challenged) by the sponsor.

Funding

The community of purpose will need a budget. This will include a budget for community meetings and travel, a time-writing budget for the community leader and potentially the core community team. The community may also need money to commission some research activities or trials on behalf of the organisation. The scale of the budget will be agreed between the community leader and the sponsor, and the sponsor will generally provide the budget from his or her own funds.

Committed membership

The community of purpose needs a committed core team. This is likely to be made up from experts and practitioners selected from the different business units, countries and regions. The core team are usually assigned, rather than being volunteers, or at least are specifically invited to join the community. There may be additional roles within the core team; some organisations assign a deputy leader, some assign a manager or facilitator and many will assign a secretary to take notes and look after logistics.

A community collaboration space

The community of purpose will work together to deliver best practice to the organisation. They therefore need a site where they can collaborate, store information and share knowledge on a continuous basis. This site could include community contacts and resources, community news and publications (for example a community blog), work in progress in the form of documents or wikis, a community calendar and a community discussion forum.

Meetings

The community of purpose should hold face-to-face meetings at least once a year, as these physical meetings are vital for building and maintaining the relationships and trust within the team, which will be necessary for effective sharing of expertise and knowledge. Given that the team is dispersed, shorter follow-up meetings will be through telephone, video and web conferences, but the community should also aim to hold a face-to-face meeting in each major region of the world at least once a year.

A supporting community of practice

Very often a community of purpose will cover the same area of practice as a community of practice. In this case, the community of purpose can act as a core team for the practice community. The core team members are the ones responsible for delivering the performance contract, the ones who have been assigned to the community of purpose, the ones invited to the community meetings and the ones who can time-write (record their time on their timesheet against the community activities) to the community budget. The members of the community of practice have no responsibility for the performance contract, are volunteers and cannot time-write. They interact with the community through online discussion and may not have full access to the community collaboration space. A community of practice with a community of purpose at the core is an example of a nested community (Figure 4.2).

Communities of purpose are used in both marketing and sales and in Mars have had widespread use in sales (see for example the Route to Mass Market GPG described in Chapter 9).

Another case study of the use of communities of purpose within sales and marketing comes from Aon Insurance. Aon set up nine communities of purpose (which they call Global Practice Groups) to cover sales, marketing and client support in their nine major global markets, such as Aviation and Aerospace, Marine and Property, each one under the lead of an executive sponsor. The purpose of the Global Practice Groups is to provide Aon’s client managers and executives with the very latest knowledge and information to help solve clients’ risk issues and so win business and sell insurance. According to the chairman of Aon’s Property Global Practice Group, Nick Maher, ‘we transact thousands of property deals every day across a broad range of businesses. Through our network of global contacts, we are able to tap into that database and compile industry-specific reports that quickly and credibly demonstrate Aon’s depth of experience and global reach in every major industry sector. We have already seen that these reports have the power to differentiate Aon from our competitors.’2

Sarah Adams of Aon tells this success story:3

Aon Australia’s Melbourne office received an invitation to tender for the insurance business of a leading Australasian toll-road company, which was held by one of Aon’s major competitors. The timeframe for the tender submission was very tight, allowing for little time to gather data and statistics. The Australian account director sent an e-mail to the Property GPG requesting urgent benchmarking information that would demonstrate Aon’s global expertise in the field of toll roads, tunnels and bridges.

Information on the insurance cover of similar companies was quickly collected from across the globe and compiled by Oliver Schofield, manager of the Property GPG. Property experts from China, Hong Kong, Canada, Brazil and Belgium sent details regarding their clients’ cover, which were anonymised to protect their identities – a good data protection policy.

The practice group was able to visibly demonstrate exactly what the toll company’s international peers were paying for property cover and provide details about limits and deductibles. Within 24 hours, Aon’s Melbourne office received the information; two days later the presentation was made to the company and less than two weeks after that Aon Melbourne was appointed as the new broker.

This case study demonstrates the role that a community of purpose can play in compiling information that bid teams around the world can use, in this case very successfully. In fact the story continues, as Aon Ireland shortly afterwards were bidding for an account for a toll-road in Ireland and were able to use the knowledge and information from the Australian account to win the Irish account as well.

Communities of interest

A community of interest is a community of people interested in a particular topic. It is not necessarily their core practice area, but it’s something they’re interested in. They may work with this topic, they may be customers of this product, they may be people with a particular problem or medical condition who could potentially be consumers of a product – the link is that they all have an interest in this topic or item. Communities of interest can exist within your organisation or can extend beyond your organisation to cover your customer base, your suppliers or your partners. The flow of knowledge and information within a community of interest is usually outwards from the core team to the interested parties. There is also a lot of value in promoting a two-way flow, so that you can learn from your customer base or you can learn from people applying a product.

For a community of interest to work well, it needs the following enablers:

A core team to coordinate the communication

The community of interest thrives on communication and on information and needs a core communications team to make sure that the information flows and that the knowledge libraries are kept up to date. This team may be as small as one person or maybe a larger team with a team leader, depending on the scale of the community and the degree of information that needs to be broadcast. An external community of interest, catering to a large community of customers, will need a permanent core team to coordinate this.

A very good knowledge of the needs of the community members

Whether the community of interest is a group of people within your organisation working with a particular product or whether it is a customer community with an interest in a particular brand, you need to understand these people very well and understand what their information and knowledge needs are. You may need to do some internal and external market research before you can plan your community strategy.

Communication tools

The community of interest needs to be able to subscribe to communications, in order to be kept up to date on their area of interest. The communication tool could be a blog, an e-mail mailing list, a Twitter feed or a newsletter to notify the community of new products, changes to existing products and upcoming events. For example, Pepsi currently4 have an @Pepsi Twitter feed with nearly 30,000 followers. They use this to interact with customers, announce events, promote products and encourage people to send in photographs of Pepsi products being consumed all over the world. Ben and Jerry’s in France have a blog promoting products, activities and their French roadshow.5 Dove has had great success releasing viral marketing videos on YouTube6 in order to market Dove within the customer community, as has Old Spice. The Purina puppy club7 is another example – a community of interest of puppy owners, sponsored by Purina pet foods. New puppy owners join the community and Purina sends them regular e-mail newsletters and updates as their puppy grows, thus providing them with information on the stages of puppy growth and at the same time subtly reinforcing the Purina brand.

Community discussion

A large part of the value from a customer community of interest comes from the ability to listen to the customer. The community of interest can conduct polls, seek feedback from customers or just listen to customer discussion. Many of the pharmaceutical communities of interest, for example, are focused on particular medical conditions and offer community interaction to allow sufferers to discuss the condition and its treatment and provide support for each other. At the same time, the pharmaceutical company can seek to understand the customer base better and so provide products that will help them. An example of this is Fibrocentre,8 the fibromyalgia community site sponsored by Pfizer. As well as providing a whole set of educational resources about the condition, this site hosts a series of ‘real patient stories’ and invites community members to send in their own stories. The Herceptin site,9 sponsored by Roche, goes further and hosts a community of HER2 + breast cancer patients, allowing connections between women fighting breast cancer, for sharing of experiences and for mutual support. The Tesco baby club10 provides a range of resources for new mothers, including a discussion forum where new mums can exchange hints on where to find maternity wear or how to encourage baby to sleep through the night. This club builds a sense of community among the young mums, promotes brand awareness and allows Tesco to promote new products such as baby food, clothes and nappies (diapers).

Knowledge base

The community of interest needs a knowledge base where they can find the core knowledge about their particular topic of interest. For an internal community, this will be a SharePoint site or a portal where they can find information on a particular product or a particular brand. The customer communities of interest that we have discussed above also contain knowledge bases. The Tesco baby and toddler club, for example, contains a wealth of advice for new parents, guiding them through their children’s development and including items such as an A to Z of child health, recipes for healthy eating, exercise and makeover tips and of course a whole range of in-store special offers. The fibromyalgia site has a whole series of guidelines on living with fibromyalgia, including a compilation of tips from other sufferers. The Amex ‘open forum’ for business owners11 provides links to experts, links to guidance for small businesses, as well as a discussion forum and a Twitter feed. They also provide a service rather like an online knowledge market (see Chapter 3), where small businesses can link with others who might be able to help them.

A social network

Part of the purpose of building a community of interest, either inside the company or with customers, is to build a social network. This is particularly important with customers, as this will underpin brand loyalty going forwards. Social networking tools can be particularly important here and many organisations are using these tools to build their customer communities of interest. However, it is important that marketers who intend to use these tools participate in a way that is sensitive and will be welcomed by the users. Users are highly empowered and not shy of stating their opinion, and a company that gets this wrong will get it publicly wrong.

An example of an organisation using social networking tools to build a powerful community of interest is the use of Facebook by Guinness. Guinness UK have a very attractive Facebook site12 with nearly 300,000 supporters, containing customer photographs, links to promotional articles, customer comments, a calendar of upcoming events and the Guinness Pubfinder.

Similarly, the Toyota Prius has its own Facebook site, with 55,000 supporters. On their site they even provide an ‘ask an expert’ service, a set of videos and a neat little game called ‘acts of kindness’, where people collaborate to suggest eco-friendly tips.

For brands with a very positive customer perception, this type of Facebook activity can really strengthen brand loyalty. Without existing brand loyalty, it can have less of an effect. This book was written at the time of the BP oil spill, and while BP America’s Facebook page13 had 33,000 supporters, this was heavily outnumbered by the Boycott BP page,14 with 775,000 supporters.

1.Otherwise known as the community facilitator, community moderator, community leader or community minder.

2.‘Practice makes perfect’, Sarah Adams, Inside Knowledge magazine, volume 9, issue 4, December 2004.

3.Ibid.

4.Summer 2010.

5.http://www.benjerry.fr/blog/

6.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYhCn0jf46U

7.http://www.purina.com.au/puppy-kitten-club/puppy-kitten-club.aspx

8.http://www.fibrocenter.com/index.aspx

9.http://www.herceptin.com/index.jsp

10.http://www.tesco.com/babyclub/

12.http://www.facebook.com/Guinnessgb