IN THIS CHAPTER

There is more than work to be done on your SUSE Linux machine. Your desktop can play music and serve as a radio. Movies are indeed made on Linux boxes. You can create and edit images of all types and move pictures from your digital camera to your PC. You can even watch TV on your monitor (with the right video card)!

Linux is not yet the gamers’ OS of choice, but there are more ways to have fun on Linux than you may have thought. You’ll learn what’s available in this chapter, too.

Because most of this is visually oriented, we’ll emphasize the tools for GNOME and KDE, but there are some interesting command-line tools for multimedia to learn about, too.

An impression exists that Linux is weak in multimedia (especially sound card) support. This is largely because of some mixed results for the very popular Creative Labs (SoundBlaster) products under Linux. Today, multimedia support is great and continually improving.

SUSE Linux supports most current sound cards out of the box. During the SUSE Linux installation, YaST should recognize and give you a default configuration for both your sound and video cards, enough to get you up and running. Although you can further configure both cards during the setup, it’s better to get your system going and then tweak later through YaST.

Sound support for SUSE Linux is provided through ALSA, the Advanced Linux Sound Architecture. ALSA began as a simple project to write better drivers for a single sound card, and it blossomed. It has been supported in the kernel since v2.5, and been the default sound system since v2.6. It supports everything from consumer sound cards to multichannel interfaces and will play multiple audio streams simultaneously if you want.

YaST handles all the configuration tasks for ALSA, and you are no longer required to load the kernel modules manually. This is the topic of the next section.

Most settings for audio and video are set in YaST. To do this, open YaST and click Hardware to start the configuration. When you click Sound, YaST checks your current configuration and displays all detected sound cards.

You can set some advanced options for the card, but unless you are trying to solve some problem and know what to change, you should leave these alone. Click Volume to change the default volume settings for every channel on your card. The Start Sequencer check box loads kernel modules for MIDI sounds at boot, and is checked by default.

If YaST does not automatically recognize your card, you can add it manually in this dialog box.

Choose the card from the menu or use the Search tool to find your card. Click Next to confirm the changes.

Reconfiguring your video card and monitor should also be done automatically if you change your hardware. Clicking Video Card and Monitor in YaST’s Hardware section will tell you the current settings. Click Change to run SaX2 (see Chapter 4, “Further Configuration with Yast2 and Sax2,” to learn more about configuring the X Window System with SaX2).

Tip

Need to test your sound quickly? Head for the KDE or GNOME Control Center and set a system notification. In KDE, go to Sound & Multimedia, and then System Notifications. In KDE System Notifications, select KDE Is Starting Up and click the > icon to play the sound. In GNOME, open Multimedia (if necessary) and then Sound. Select the Sound Events tab and pick a random sound (you must have the gnome-audio package installed for the default sounds to work).

After your sound card is working, perhaps the only thing you want to do, audiowise, is to play your CDs and MP3s, and access your favorite Internet radio stations. SUSE Linux provides a wealth of ways to do this and more.

The most mature all-purpose media player for Linux (and all X Window Systems) is the X Multimedia System (XMMS). XMMS modeled its GUI after Winamp, the popular media player for Windows.

Its display is very modular, so you can have as much (or as little) eye candy to visually enhance your audio experience. Figure 10.1 shows what happens if you display everything in a default installation.

Figure 10.1. Arrange the XMMS display any way you like to enhance your audio experience. Equalizers, playlists, sound analyzers, and oscilloscope meters are all showing here in addition to the simple player in the upper left.

XMMS plays most every audio format, with the exception of Windows Media (.wma, .asf) files. It will play your audio CDs out of the box, as well as MPEG movies.

If you have a live Internet connection, both XMMS and the KDE CD player (KSCD) will contact the CD Database (CDDB) of your choice (XMMS defaults to FreeDB) to deliver track information when you play a CD.

Digital sound recordings appear in several formats. You can create and listen to files in the following formats with SUSE Linux:

Raw—More properly known as the headerless format, audio files using this format contain an amorphous variety of specific settings and encodings. All other sound files have a short section of code (the header) that identifies the format type.

MP3—Perhaps the most popular audio format ever. MP3 uses a commercial, proprietary compression scheme, which can create licensing issues for both creators and users.

WAV—These days, WAV (Windows Audio Visual format) files are mostly used as brief sound effects to accompany error messages and other computer events. This is because WAV files are not compressed and so take up a lot of room even for a short clip.

Ogg-Vorbis—This format is the open source competitor to MP3. You’ll enjoy better compression, better audio playback, and you can’t be sued for using it.

Tip

Want to learn more about these and other audio formats? Head over to the Audio Format FAQ at http://www.cnpbagwell.com/audio.html.

Should you need to convert an audio file from one format to another, various utilities can help you do that. The best known is Sound Exchange (SoX). This command-line utility is not installed by default, but you can get it via YaST.

Timidity is a cross-platform MIDI-to-WAV converter and player. It handles karaoke files, too, displaying the words so you can sing while it plays.

One of the best things about your Internet connection, even under dial-up, is the capability to hear hundreds of radio stations broadcasting music, news, and information globally through the World Wide Web. What was once the province of hobbyists with expensive radio equipment is now available to anyone with an Internet connection.

Streaming audio comes in four formats: RealAudio, MP3, Ogg Vorbis, and Windows Media (wma). SUSE Linux media players handle all these formats except for Windows Media.

XMMS does streaming audio quite well, though occasionally it will ask you for a file to play.

The Linux player made for streaming audio is the Helix Community Player. RealNetworks open-sourced the code for its various media formats and the RealPlayer client some time ago.

SUSE Linux 9.2 was the first SUSE version to come equipped by default with RealPlayer Gold, although earlier UNIX versions of the RealAudio player worked with Linux. RealPlayer (owned by RealNetworks) and its completely open-source cousin, the Helix Community Player, play most audio types, streaming or not. SUSE Linux 10 includes RealPlayer 10.0.5 in both the open-source and retail versions.

If you happen to be fond of the built-in browser included in the Windows version of RealPlayer, you may be disappointed with the Linux version, but even though it may lack visual appeal, it performs its actual function—playing audio—quite well.

Note

If you’re running SUSE Linux 9.2 on a 64-bit processor, you may have trouble running RealPlayer inside Mozilla-based browsers (including Firefox, Epiphany, and Galeon). The 32-bit RealPlayer package included with the distribution does not install the Mozilla plug-in, and attempting to install it manually results in the browser crashing on launch. The Helix community is working on a 64-bit version of both the Helix and RealPlayer applications, including the plug-ins, which may be released by the time you read this.

RealPlayer works fine as a standalone player under an AMD Athlon 3000+.

Both versions of the Helix player have the plug-in architecture that should, in time, yield a player that does what every user wants it to. This depends on whether enough users make their wishes known.

SUSE Linux has a number of tools to help you record your own sounds.

Icecast is a streaming-audio server application that enables you to play your MP3 collection over a LAN, or even over the Internet.

Burning your own CDs is a fundamental skill for Linux multimedia enthusiasts. Compact discs and digital versatile discs (DVDs) are the standard media for multimedia data of all types because they are cheap to produce, ultra portable, and can hold the large files that carry audio, and especially video, signals. Even the standard three-minute pop song requires a few megabytes of space to store. For multimedia, you can use CD/DVDs to

Record, play, and store graphical images, music, video, and playlists

Rip audio tracks from your own music CDs and create “mix tapes” to your liking

Of course, CDs can store many other types of files, not only audio and visual files. They are an excellent medium for storing backups of all data stored on your hard drives. See Chapter 20, “Managing Data: Backup, Restoring, and Recovery,” for more information.

It may be obvious to state, but if you want to record multimedia (and other) data on a CD, you must have a drive that supports writing data to discs. A simple CD-ROM player does just that—plays already-recorded material that is read-only. What you need is a CD-RW (Read/Write) or DVD-RW/DVD+RW drive. The discs themselves must also be writable (CD-R or CD-RW and the corresponding DVD formats). YaST will configure your hardware at installation; see Chapter 4 to see how that is done. To ensure that your hardware is configured properly, use cdrecord -scanbus to get information on using the CD drive under SCSI emulation. When you type the following:

cdrecord -scanbus

You should see something like this:

Cdrecord-Clone 2.01 (x86_64-suse-linux) Copyright (C) 1995-2004 Jörg Schilling Note: This version is an unofficial (modified) version Note: and therefore may have bugs that are not present in the original. Note: Please send bug reports or support requests to http://www.suse.de/feedback Note: The author of cdrecord should not be bothered with problems in this version. Linux sg driver version: 3.5.27 Using libscg version 'schily-0.8'. cdrecord: Warning: using inofficial libscg transport code version ([email protected] '@(#)scsi-linux-sg.c 1.83 04/05/20 Copyright 1997 J. Schilling'). scsibus0: 0,0,0 0) 'LITE-ON ' 'COMBO SOHC-5232K' 'NK07' Removable CD-ROM 0,1,0 1) * 0,2,0 2) * 0,3,0 3) * 0,4,0 4) * 0,5,0 5) * 0,6,0 6) * 0,7,0 7) * scsibus2: 2,0,0 200) 'Memorex ' 'TD 2C ' '1.04' Removable Disk 2,1,0 201) * 2,2,0 202) * 2,3,0 203) * 2,4,0 204) * 2,5,0 205) * 2,6,0 206) * 2,7,0 207) *

The CD writer is present and is known by the system as device 0,0,0. The numbers represent the scsibus/target/lun (logical unit number) of the device. You will need to know this device number when you burn a CD from the command line, so write it down or remember it.

When you’re first getting started with CD burning, it’s good to have the comforting approach of a GUI wizard to walk you through the process. You can tackle the command-line approach eventually, but because SUSE Linux offers a pair of very good GUI tools for burning multimedia discs, you are indeed in good hands. In this section, you’ll first learn about the CD creation tools that come with KDE and GNOME. Then you’ll see the shell tools that let you burn at your keyboard.

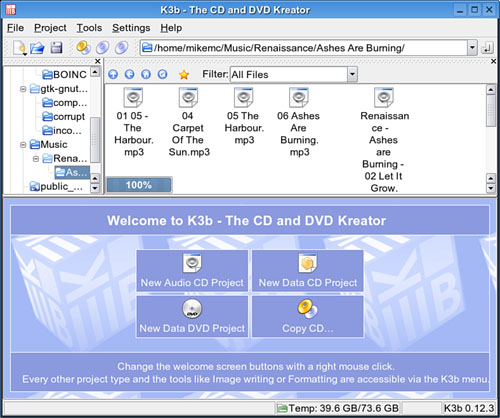

KDE’s graphical CD/DVD “Kreator” is called K3b, and it makes CD burning pretty much a matter of dragging and dropping files into a project and going about your business.

Perhaps it’s not quite that simple, but close enough for rock ‘n’ roll (or whatever style you prefer).

When you open K3b (see Figure 10.2), you see a familiar three-pane interface. On the upper left is your directory structure, with your last directory selected. In the upper right are the files contained in the selected directory. At the bottom is where the action happens. K3b offers four options in the main window:

Figure 10.2. K3b knows what the typical CD-burning projects are and puts them in easy reach on the main screen.

New Audio CD Project

New Data CD Project

New Data DVD Project

Copy CD

These items are not the only things you can do with K3b, but they are the most typical. Go to New Project in the File menu to see your other selections.

Tip

The Copy CD feature in K3b is pretty cool. Want a copy of a favorite CD to play in your car while the original sits in your home stereo? Put that CD in your computer’s drive. Run K3b and choose Copy CD (you may have to turn off the default CD player first). K3b will first copy the tracks of the CD to a temporary directory on your hard drive. It will then prompt you to insert a writable CD and burn the tracks to the blank CD.

Let’s make an audio CD. Click the appropriate button and the bottom pane effectively becomes a representation of your CD. Find your digital music files using the two upper panels, and drag the files you want to burn into the bottom pane. K3b should identify the track information from the tags included in every digital music file. If you don’t see the title, artist, or other information for a track in the pane after you drag them in, select the track and click Query Cddb if you are online to check the CD Database, or type the information in yourself.

As you drag files into the bottom pane, the progress bar tells you how much room you have remaining on the disk. When you have dragged all the files you want (or have reached the end of the disc), you can rearrange them in any order you want. To create an ordered M3u playlist file for your MP3 audio files, click the Convert Audio Tracks icon from the toolbar and check the box. You can also use this dialog box to convert files from one audio format to another if you choose.

When all is well, and you have your tracks in order, click the Burn button on the toolbar. Another dialog box will appear. If you want to give your CD a title, click the Description tab in this dialog box. There are many settings available here, but accepting the defaults is the way to go for the novice. Click OK to start burning. A progress bar will appear to let you know how the burn is going. When the burn is complete, K3b will eject your new CD and play a happy bugle tune to announce its success. Your new CD will now play in any computer, stereo, or other CD player.

In GNOME, basic CD burning is built right in to the Nautilus file manager. Insert a blank CD in your CD-RW drive. Go to the Places menu in Nautilus and select CD/DVD Creator. Open a second (or more) Nautilus window(s) containing the files you want to burn to the CD. Drag and drop the files into the CD/DVD Creator window (which is really a special directory called burn:///).

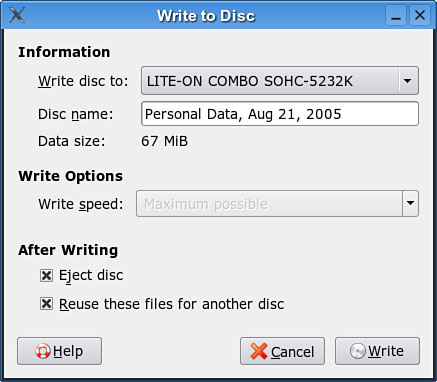

When you have your files selected, select Write to Disc from the File menu in the CD/DVD Creator window. This opens a dialog box (see Figure 10.3) where you can name the CD. There are no special features for building multimedia collections (such as playlist orders), but if you just want to get some files (music or otherwise) onto a CD or DVD, Nautilus gives you the tool to do that.

Under the hood of the CD writing process, you’ll find that this takes two steps. First, you create the iso9660-formatted image, and then you burn (or write) that image onto the CD. The iso9600 is the default file system for CD-ROMs.

Use the mkisofs command to create the ISO image. This command has many options (see the man page for a full listing), but use the following for quick burns:

mkisofs -r -v -J -l -o /tmp/our_special_cd.iso /source_directory

The options used in this example are

-r—Sets the permission of the file to more useful values. UID and GID (individual and group user ID requirements) are set to zero, all files are globally readable and searchable, and all the files are set as executable (for Windows systems).-v—Displays verbose messages (rather than terse messages) so that you can see what is occurring during the process; these messages can help you resolve problems if they occur.-J—Uses the Joliet extensions toISO9600so that Windows can more easily read the CD. The Joliet (for Windows), Rock Ridge (for Unix), and HSF (for Mac) extensions to theISO9600standard are used to accommodate long filenames rather than the eight-character DOS filenames that the standard supports natively.-l—Allows 31-character filenames; plain DOS will not like it, but everyone else does.-o—Defines the directory where the image will be written (that is, the output) and its name. The/tmpdirectory is convenient for this purpose, but the image could go anywhere that you have room and write permissions./source_directory—Indicates the path to the source directory—that is, the directory containing the files you want to include on your CD. There are ways to append additional paths and exclude directories (and files) under the specified path; it is all explained in the man page if you need that level of granularity. Our simple solution is to construct a new directory tree and populate it with the files we want to copy, and then make the image using that directory as the source.

Many more options are available, including options to make the CD bootable.

After you have created the ISO image, you can write it to the CD with the cdrecord command.

cdrecord -eject -v speed=12 dev=0,0,0 /tmp/our_special_cd.iso

The options used in this example are

-eject—Ejects the CD when the write operation is finished.-v—Displays verbose messages.speed=—Sets the speed; the rate depends on your drive’s capabilities. If the drive or the disc itself does not support a faster speed (or burns poorly at the higher speed), you can use lower speeds to get a good burn.dev=—Specifies the device number of the CD writer (I told you that you’d need this).

Tip

If you have CD-RW (read/write) discs, you can use the cdrecord blank= option to erase all the existing files on the CD.

cdrecord also gives you the option (when the disc supports it) of making multisession CDs. Without this option, when you remove a CD from the drive after writing files to it, your disc can no longer be written to, even if it still has space available. Using cdrecord -multi gives you the choice to put more files on the disc later.

Current standard capacity for a CD is 700MB of data, or 80 minutes of music. Some CDs can be overburned; that is, recorded to a capacity higher than the standard. You can overburn with cdrecord as long as your drive supports it. Find out more at http://www.cdmediaworld.com/hardware/cdrom/cd_oversize.shtml.

Many new computers now come with DVD-writing drives, and costs have come down to where ordinary users can buy them as well. Unfortunately, the standards-making bodies have not kept up with the increasing availability of these drives, so there are two competing formats for writing DVDs. Commonly known as the + and–formats, DVD+R, DVD+RW, DVD-R, and DVD-RW are the ones we have to live with for now.

Differences between the two have mostly to do with how the data is modulated onto the DVD itself, with the + format having an edge in buffer underrun recovery. How this is achieved impacts the playability of the newly created DVD on any DVD player. The DVD+ format also has some advantages in recording on scratched or dirty media. Most drives support the DVD+ format, and some support both.

This section will focus on the DVD+RW drives because most drives sold support this standard. The software supplied with SUSE Linux supports both formats. It will be useful to read the DVD-writing HOWTO at http://fy.chalmers.se/~appro/linux/DVD+RW before you use these command-line tools. You can skip over the part in the HOWTO with a detailed explanation of how things are done in the kernel to record DVDs. Read the stuff on the tools, though.

You need to have two packages installed to make DVD recording possible: dvd+rw tools and cdrtools. The dvd+rw tools package includes the growisofs application, which acts as a front end to mkisofs as well as the DVD-formatting utility.

You can use DVD media to record data in two ways. The first is much the same as that used to record a CD in a “session,” whereas the second way is to record the data as a true file system using packet writing.

To record data in a session, you use a two-phase process:

Format the disc with

dvd+rw-format /dev/scd0(necessary only the first time you use a disk).Write your data to the disc with

growisofs -Z /dev/scd0 -R -J /your_files.

The growisofs command simply streams the data to the disc. For subsequent sessions, use the -M argument instead of -Z. The -Z argument is used only for the initial session recording. If you use -Z on an already used disk, it will erase the existing data.

Caution

Some DVDs come preformatted. If this is the case and you format them again, the disc may become useless. Always be sure to read the fine print on the packaging on the DVD+RW before formatting.

Tip

When you write your first session on the DVD, cover at least one gigabyte (1GB). This helps ensure compatibility with other optical drives. DVD players calibrate themselves by attempting to read from specific locations on the disc. Data has to be present for the drive to read it and calibrate itself.

Also, because of limitations in the standard ISO9660 file system in Linux, do not start new sessions of a multisession DVD that would create a new directory past the 4GB boundary. If you do, it will cause the offsets used to point to the files to “wrap around” and point to the wrong files.

Packet writing treats the DVD like a hard drive, where you create a file system (like ReiserFS) and “format” the disk. You can then write to it randomly as you would a hard drive. This method, although common on Windows computers, is still experimental for Linux and so is not covered in detail here.

It is possible to pipe data to the growisofs command:

your_application | growisofs -Z /dev/scd0=/dev/fd/0

It’s also possible to burn from an existing image (or file, named pipe, or device):

growisofs -Z /dev/scd0=image

The DVD+RW Tools documentation, found in /usr/share/doc/dvd+rw-tools, is required reading before your first use of the program. Try experimenting with DVD-RW media first; DVD-R discs are not quite as cheap as CD-R disks, thus making the penalty for making mistakes somewhat higher.

Standard video cards let you see most video resources, as you would expect. What you may not know is that you can turn your monitor into a television screen to receive TV signals with a TV or TV/video combo card. This section describes a sampling of Linux software that works with these content types.

Make sure your cards are properly configured. (See Chapter 4 to configure your hardware cards with YaST and SaX. See Chapter 6, “Launching Your Desktop,” for configuring X.)

Video support in Linux comes through the V4L (Video for Linux) API, or directly through the X Window System. Support for TV display from video cards with a TV-out jack is poor at this time. TV-only cards are well supported, but you must know the chipset name of your card, not the manufacturer’s brand name. The most common chipset is the Brooktree Bt series; the Linux driver is called bttv.

YaST should recognize your card, if it is supported, and load drivers, whether the card is present at your initial SUSE Linux install or is added later. If this doesn’t happen, you can always configure the card manually.

To configure the card, you need to identify the chipset. Check YaST. Go to Hardware, then Graphics Card and Monitor, or TV Card.

Personal video recorders like TiVo and ReplayTV have changed the way people use television. The VCR introduced the idea of time-shifting broadcast television, but developed the reputation of being so complicated to program that nontechnical folks threw up their hands and gave up. Technical advances have made this easier, but the image of the “guy who can’t program his VCR” persists. PVRs automate the hardest part of this task and make it a virtual no-brainer to record both analog and digital TV signals to a hard drive for later viewing.

TiVo itself runs Linux on a PowerPC processor to record shows on its hard drive.

Several open-source projects have been launched to create PVRs on Linux. The most successful of these is the MythTV project. The goal of MythTV is to bring the “mythical digital convergence box” to life, so it has the TiVo features, a web browser, an email client, games, and a music player.

Installing MythTV under SUSE Linux is not for the faint of heart, but it can be done. YaST will help along the way, dealing with various software dependency issues that might not be solved through compiling packages one by one.

This is not a project to give your old Pentium II machine a new life. Processing TV signals requires a big and fast microprocessor chip and a good monitor. To make this work, you need modern equipment. Check the PVR Hardware Database at http://pvrhw.goldfish.org/tiki-pvrhwdb.php and compare these systems to the SUSE Hardware Database to pick the best PVR system for you. Hauppage, the maker of several popular TV cards, recommends a Pentium III processor at 733MHz (or 1.8GHz to make DivX video) for its PVR cards. You should also have a high-speed (DSL or cable modem) connection to the Internet to access TV schedule information. In addition, MythTV sets these guidelines:

256MB memory

40GB (or larger) hard drive

XFS or JFS file system (which handles large files better than other file systems)

A video card with a TV-out port

A video capture card

You have two basic options for video capture: a “frame grabber” that is software driven or a more expensive MPEG encoder. The frame grabber does its encoding using the PC’s resources, whereas the onboard encoder does it itself. The trade-off is that the IvyTV drivers needed for the encoder are somewhat troublesome to install.

If you have the right machine, let’s start setting it up.

Follow these steps to build your personal video recorder. Read the online MythTV installation guide before or during your setup. It will be very helpful. Find it at http://www.mythtv.org/docs/mythtv-HOWTO.html.

Tip

These instructions make use of two online tools to update and install software on your SUSE Linux system: YaST Online Update and Apt. Find out more about these in Chapter 21, “Keeping Your System Current: Package Management.”

If you haven’t already, install SUSE Linux. Make sure you have the

qt3, qt3-devel, qt3-mysql, gcc, freetype2-devel, andmysqlpackages installed.Run YaST Online Update to confirm that everything’s current.

If apt is not yet installed, install it. See Chapter 20 for instructions.

Open a shell or console and log in as SuperUser.

Open

/etc/apt/sources.listin a text editor and add this line:rpm http://folk.uio.no/oeysteio/apt suse/9.2-mythtv MythTV. This site contains MythTV RPMs for SUSE Linux v9.0, 9.1, and 9.2 (change the version number as necessary). If you have an MPEG encoder card, add this line as well:rpm http://folk.uio.no/oeysteio/apt suse/9.2-ivtv IvyTVfor the IvyTV packages.Type

apt install xmltv zap2it lame mythtv. This will install MythTV and any other necessary package. This will likely take some time.Setup the Myth MySQL database. Type

mysql -u root < mc.sqlat the shell.Go to http://www.mythtv.org/docs/mythtv-HOWTO.html#toc5.4 and follow the instructions on setting up Zap2It DataDirect to handle your scheduling needs.

Decide where in the file system you want to store your recorded video. By default, MythTV stores files in

/mnt/store. You may have to create this directory; make sure that at least one user can write to that directory. You may also want to create a user mythtv to be that user. If you prefer to store the files elsewhere, you’ll need to edit the MythTV configuration file later.Go to the MythTV setup directory and type

./setup. Follow the prompts to go through the initial configuration. Accepting the default settings should get you in no trouble.After you have completed the setup, it’s time to go back to being an ordinary user. If you have created a separate user, mythtv, log out and log back in as mythtv (otherwise, just exit the SuperUser shell).

Running MythTV is a two-step process. First, run

mythbackendto open the database, and then runmythfrontendto view your content.

And so you have your own PVR, with no service to buy. There are lots of other options in setting up MythTV; read more about them in the MythTV manual.

A digital camera combined with your personal computer is a powerful tool to create, store, edit, print, and share images. You can take your pictures, store them initially on the camera’s disk or memory card, and then transfer them to your PC with the camera’s USB cable. View or edit the file with your favorite image editor, then email photos to friends and family, post them on your photo blog, or preserve the images on a recordable CD. No fuss, no muss, no film.

Unfortunately, some of the pleasure and convenience associated with digital cameras are lost when running Linux. Most, if not all, of the software bundled with your camera runs only on Windows.

Do not despair, however. SUSE Linux offers many tools to organize and share your photos, and because the digital imaging industry is organized around very common standards, Linux can handle most any task involving your camera.

To begin with, you should have no trouble connecting your camera to your Linux system. Just connect the camera with its Universal Serial Bus (USB) cable to your PC. SUSE Linux should recognize the camera instantly and install the proper drivers. If you have any doubt that your camera is connected, run the following shell command:

cat /proc/bus/usb/devices

After you have the camera connected, use any file manager to see the image files on your camera. They should be located in /dev/sda1, the first SCSI data device, unless you have a SCSI hard drive installed, in which case the images will be on /dev/sda2.

GNOME has a camera-support tool called gtkam. This is a GTK+ front end to the command-line gphoto software. To run it, go to the Graphics menu and click Digital Camera Tool. The first time, it will ask you to identify your camera model from the list of 500+ cameras it supports. After you have your camera configured, gtkam will help you download your images from the camera to your PC. Just click the thumbnail to select.

KDE fans can use the digiKam tool to handle similar tasks. It also is a KDE-based front end to gphoto, but includes an image editor as well. DigiKam will attempt to autodetect your camera, or you can add it manually. You can create photo albums for specific events.

When your images are on your computer, feel free to run them through The GIMP to enhance them. The GIMP can reduce red-eye problems, crop your photos, change colors, brightness, and contrast, and otherwise doctor up your pictures. See the next section for more fun with The GIMP.

Webcams are typically small low-resolution cameras connected to your computer via a parallel or USB port. The camera can act in two modes: streaming (for a series of images or a moving object) and grabbing (for a single still image). The most common use for webcams includes videoconferencing and the widespread phenomenon of looking in on what’s happening on a street corner where a local news organization has set up a camera. Webcams can be used to send almost-live images of assorted people, places, and things to an online correspondent. Perhaps even you’ve sent off a quick image of yourself—because you can!

You can use any of the video applications that can access a video4linux device to view webcam or still-camera images in SUSE Linux. You can also use GnomeMeeting (discussed in Chapter 16, “Collaborating with Others”) as a webcam viewer.

Not all webcams are supported in Linux, and the drivers are based on the chipset used, rather than on the model or manufacturer. Some of the kernel source documentation files in /usr/src/linux-2.6/Documentation/usb contain information about USB webcams and drivers supported in SUSE Linux, including

ibmcam.txtov511.txtphillips.txtse401.txtstv0608.txt

A good place to start with your webcam is, as always, the Linux Documentation Project. The Webcam HOWTO is located at http://www.tldp.org/HOWTO/Webcam-HOWTO.

Time was when the GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) was touted as the “killer app” that would drive ordinary desktop users to Linux. A professional image editor whose features rivaled the fabled Adobe Photoshop on Windows that didn’t cost several hundred dollars (well, one that didn’t cost anything) is just what people need, some analysts thought. It didn’t happen exactly that way, but it remains reasonable to say that Linux for the masses wouldn’t be here if not for The GIMP.

Tip

To learn more about the role of The GIMP and the toolkit that spawned dozens of GUI products, see the section on GNOME in Chapter 6.

Photographers, animators, web designers, and other artists use The GIMP in all sorts of ways. The nonhuman characters in the Scooby Doo movies were created with the help of a GIMP spinoff now called CinePaint.

So what can you do with The GIMP? Just about any photo or other graphic-editing task. The GIMP can import and export more than 30 image formats, including Photoshop’s native format. It supports layers (letting you easily add and remove text or other effects from an image) and has all the tools people expect from a modern image editor.

Version 2.2 of The GIMP, released in December 2004, features a more usable interface, better drag-and-drop support, and a shortcut editor.

To run The GIMP from the shell, type gimp &. The ampersand (&) launches The GIMP in the background and returns you to the shell prompt.

Otherwise, The GIMP can be found in the Graphics menu in the KDE or GNOME start menus. The first time you run The GIMP, you’ll be asked a few startup configuration questions, but then you’re on your way.

When you open The GIMP without an image, you’ll see the toolbox first; these icons offer the basic utensils for editing an image. Depending on the version installed on your system, more than 30 tool icons could be available to you in the toolbox.

To create a new image, press Ctrl+N (or go to File, New). To open an existing image for editing, press Ctrl+O and an image window appears. Both the toolbox and the image window have their own menus. Open the File menu in either window to open and save graphics and perform other file-management tasks. The Toolbox Extensions menu (Xtns) contains the plug-ins and other enhanced functionality that make The GIMP special.

Right-clicking anywhere in an image window also gives you access to a context menu with a wealth of choices to work with your image (see Figure 10.4).

In the right edge of the menu are two important options, Python-fu and Script-fu. Both offer ways to automate tasks and do all sorts of cool things. Script-fu is the original GIMP scripting language, but because it’s based on a relatively obscure programming language, Scheme, it’s hard to learn. GIMP 2.0 introduced Python-fu, based on the famous (and famously easy to use and learn) Python scripting language.

The GIMP’s Help files are quite good. It doesn’t hurt for newbies (either to The GIMP or to image editing in general) to read the manual.

When you work with digital images, there seems to be a million different formats. Despite what you may believe, each format exists for a specific reason, either technical, aesthetic, or legal/financial. Some formats are patented or have patented technology included.

When you’re working with editors such as The GIMP, choose the right format for the task at hand. Following is a list of some of the more popular formats, followed by an explanation of why you might want to use (or not use) them.

BMP—Bitmapped graphics, which are commonly used in Windows. They are large and uncompressed files, good for icons and wallpaper.

GIF—Graphics Interchange Format. Most graphics on the web once used this format, developed by CompuServe, one of the original online services. GIF uses a patented lossless compression algorithm (LZW) that requires a license to use.

JPEG—The Joint Photographic Experts Group developed this format for electronic photographs. All digital cameras produce this format by default. The compression scheme loses some data, but provides a sharp image nonetheless.

PNG—Portable Network Graphics. The open source replacement for GIFs.

SVG—Scalable Vector Graphics. The Next Big Thing, this web graphics standard is being developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

TIF—Tagged Image File. Often used for printing and publishing.

Sometimes you may not be able to work with a file in its current format. Coming to your rescue are a host of separate image-converter applications that can change an image’s format almost instantly. The best known of these, ImageMagick, even does its thing from the command line!

As the original “hobby” operating system, some Linux users have all their fun just tweaking the OS and their applications. Others need more traditional entertainments. SUSE Linux is fully equipped with assorted options for the gamer in you.

Very few shrink-wrapped commercial PC games are produced for Linux. For the most part, games are developed these days for Windows PCs using the Direct3D graphics engine. The cross-platform OpenGL engine is used for many popular games (like Doom III), but there’s a perception that OpenGL is not as muscular.

Tip

TransGaming Technologies has an engine, Cedega, that converts Direct3D games to OpenGL. This enables Linux users to play as many as 300 Windows and online games, including multiplayer role-playing games such as Everquest and Star Wars Galaxies. View the supported games database, with some player ratings, at http://transgaming.org/gamesdb/.

You must subscribe to TransGaming’s service, at $5 per month, to get Cedega. Depending on what you play and how often you play it, this might be worth it. See http://www.transgaming.com/ for more information.

Many dedicated fans have worked on open-source clones of some classic games, like PacMan, Tetris, and SimCity (called LinCity). And it wouldn’t really be a computer without a solitaire game, would it (see Figure 10.5)?

SUSE Linux gives you two solitaire games, KPatience for KDE and PySol—the latter is written in Python. KPatience is installed by default with the KDE-Games package. It has 14 standard games for your amusement. One nice feature is that it will automatically play aces and other scoring cards.

PySol is much flashier, with musical accompaniment (yes, you can turn that off), dozens of games and card sets (sorted by type), and gobs of statistics. It is endlessly configurable to stave off boredom.

KDE comes with 27 games in five categories: Arcade (with 8 games, including adapted classics such as Asteroids and Tron), Board (another 8 choices including chess and backgammon), Card (just three: Poker, Patience, and Skat), Strategy and Tactics (seven games that make you think), and Kids (only one not called “Edutainment”: Ktuberling, a Mr. Potato Head editor).

Use the KDE Kicker menu to start any game. Sometimes there will be a configuration screen on first-time use, but most times you can play these right away.

The package of games that comes with GNOME is smaller than the KDE collection (just 17), but equally challenging. There’s also some overlap, with the usual Tetris clones, disk-flipping, and solitaire games.

One standout is the Yahtzee clone, Tali. This game has great graphics, and you play against five computer opponents by default. This is, of course, configurable. The five dice roll automatically. You click the dice you want to roll (which turn into pumpkins) and click Roll to try to improve your score. After your third roll, you click the category you want to count your score.

GNOME also has a blackjack table for your gambling pleasure. Learn to double-down, split your hand, and other tricks of the trade without risking any real cash. The dealer plays under any of four sets of rules, called Vegas Strip, Vegas Downtown, Atlantic City, or Ameristar. This is set in the game’s Preferences.

To play games, go to the GNOME menu, and click Games. All your choices will come up; they are not organized by type.

Sid Meier’s Civilization is one of the most popular games ever. The chance to build a society from scratch, fight wars, and get to space is irresistible for some. Naturally, some game players run Linux for more serious pursuits. What is interesting is that for some of those players, one of their serious pursuits became creating the game.

The Freeciv project was born in November 1995, about a year after the release of Civilization 1. Freeciv 1.0 came out six weeks later, though a flurry of updates produced v1.0f three weeks later. By the time Civilization III came out in October 2001, Freeciv was up to v1.12, and v2.0 was released in May 2005. SUSE Linux 10 includes v2.04.

You can play by yourself with the computer as your opponent(s), play with friends across a local area network, or use the Freeciv metaserver to play with other folks across the Internet. If you have played the commercial version, you’ll be impressed with the similarities, although the quality of the graphics may vary depending on your video card. New players should not be intimidated, because there is a fair amount of help available, both in the game itself and at the Freeciv website (http://www.freeciv.org).

In Freeciv, you are the absolute ruler of your race. You marshal and manage resources to build cities. As in other city-simulation games, you must keep your citizens happy while getting them to produce more wealth, which you then can tax. Meanwhile, you try to increase your scientific and military capacity as you aim to either achieve world domination or build the first rocket to Alpha Centauri.

Most games have just one executable to run; Freeciv has two. To play on your own machine, you first need to run the server application, which contains the maps and most game details. You create AI opponents on the server as well to give you some competition if you’re playing alone or with just one or two friends.

New players (especially those who haven’t played Civilization) should read the online manuals at the Freeciv website to get a feel for how things work. There are three manuals: more technical, command-oriented manuals for the client and server and a game-playing manual that describes the forces and conditions of the game. The manuals are not complete (especially the client manual), but give you enough of a start to keep going.

http://www.alsa-project.org/alsa-doc—The Advanced Linux Sound Architecture sound card matrix. Check here for more information on support for your card.

http://cdb.suse.de—The SUSE Hardware Database. Search here first for your sound and video cards before installing SUSE Linux.

http://www.linux-sound.org—From music made with Linux to musician mailing lists to player and production software, the jumping-off point for sound and music under Linux.

http://www.djcj.org/LAU/guide/index.php—The Linux Audio Users Guide.

http://www.xmms.org/—Home of the X Multimedia System (XMMS). News, downloads, plug-ins, skins, and support for this multifaceted media player.

http://helixcommunity.org—Many projects related to the open source Helix player, server, and producer for RealPlayer content.

http://www.vorbis.com—Hows and whys for the Ogg Vorbis audio format.

http://www.exploits.org/v4l/—Video for Linux information page. Technical information on the V4L APIs, drivers for supported cards, and personal video recorders. Links to software for making video of all types. When typing this URL, note that the last character is an L (as in Video4Linux), not a numeral 1. Should you type the numeral, you get a rather snarky error message.

http://pvrguides.no-ip.com—Guides to setting up PC-based personal video recorders with MythTV and the VDR system.

http://www.mythtv.org—The MythTV personal video recorder software. Contains installation instructions and examples of MythTV in action.

http://anandtech.com/linux/showdoc.aspx?i=2190&p=1—A detailed and honest explanation of a successful MythTV installation on SUSE Linux.

http://www.mplayerhq.hu—The MPlayer headquarters for that varied and full-featured video player.

http://xinehq.de—The Xine headquarters. News and downloads for this video player.

http://www.gphoto.org/—Linux Management software for digital camera images.

http://www.gphoto.org/proj/libgphoto2/support.php—The gphoto list of supported cameras.

http://www.teaser.fr/~hfiguiere/linux/digicam.html—Digital Camera Support for UNIX, Linux, and BSD. If your camera is not on the gphoto list, this site may help you find out why and offer suggestions.

http://digikam.sourceforge.net—The KDE digiKam front end for gphoto. Look here for plugins and new versions, which seem to come out every two months.

http://www.gimp.org—The very well-organized home of the GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP). Check out the Tutorials section, with walk-throughs for all skill levels, beginner to expert.

http://gug.sunsite.dk—The global GIMP User Group. Mailing lists, a large gallery of images and textures, tutorials, and articles to help make you a better GIMPer.

http://icculus.org/lgfaq—The Linux Gamers’ FAQ. Get your questions answered.

http://www.happypenguin.org—The Linux Game Tome, a catalog of Linux games of all sorts. Player ratings, news, forums, and links.

http://linuxgames.com—LinuxGames, with all sorts of news related to the topic.

http://www.kde.org/kdegames—The KDE Gaming area, with descriptions of all the games included with KDE.

http://www.ggzgamingzone.org—Play Linux games online for free.

http://www.freeciv.org—The Freeciv wiki site. All things Freeciv, with translations in seven European languages.