214 ◾ Security Strategy: From Requirements to Reality

of intelligent processing capabilities to reduce network bandwidth utilization, facilitate accurate

responses, and improve reporting. e following actions are recommended to facilitate the transi-

tion of application-level alerts and audit trails:

1. Survey existing application log (audit trail) collection and processing mechanisms and asso-

ciated interfaces to determine application requirements and identify gaps in capability.

2. Review existing alerting message formats and audit record formats to identify gaps in infor-

mation completeness, clarity, and the like.

3. Assess the risks associated with existing time interval standards for alert forwarding.

4. Update existing standards to conform to security strategic objectives.

5. Build a database of existing security-related audit record formats.

6. Review and update application development processes (in-house or contracted) to incorpo-

rate transition requirements into all development eff orts (in-house and contracted).

7. Create or update your CCD architecture and component requirements.

8. Defi ne and incorporate transit commonality requirements for commercial off -the-shelf

(COTS) products into procurement standards.

9. Review your corporation’s data-retention policies to determine how they will impact your

data management schema for collector and consolidator systems.

10. Review and update security policies to require all application auditing and alerting func-

tionality to conform to CCD control objectives.

11. Where applicable, form a team to work on CCD-based processing and reporting for logical

and physical access control systems.

Rapid Response

is chapter began with a discussion of the existing gaps in application-level security, including

missing or ineff ective preventative and detective controls and how these gaps have led to massive

data losses. Hopefully, the previous sections of this chapter have provided some solid tactics to

Table 11.4 Transition Control Objectives (continued)

Attribute/Control Type Risk and Requirements

Correlated Soft The relationship between the records should be apparent.

Economy

Intelligent Soft Transit mechanisms, whenever possible, should have features

that improve the accuracy and effi ciency of alert and audit

record processing and distribution such as the ability to:

- Consolidate multiple occurrences of an event within a certain

time frame into a single record.

- Generate alerts based on threshold triggers (e.g., too many

events within a certain time frame) instead of on every

occurrence of an event.

- Filter out irrelevant audit events.

- Be remotely confi gurable.

TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 214TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 214 8/18/10 3:11:04 PM8/18/10 3:11:04 PM

SDL and Incident Response ◾ 215

attack and close these gaps. is section will address two additional types of controls: corrective

and restorative. Corrective tactics are used to respond to and resolve security incidents to reduce or

eliminate potential damages. Actions may be people, process, or technology based—for example,

a guard stopping someone who tailgated through a security access point, a manual procedure for

removing malware, or a programmatic countermeasure that kills an attacker’s TCP/IP session.

Restorative controls are controls that return systems to normal production operations after they

have experienced an incident. is includes system rebuilds, restores from backup, as well as busi-

ness continuity planning (BCP) and disaster recovery planning (DRP) procedures. is section will

also touch on nonincident-related responses, such as compliance and security status reporting.

A large body of knowledge surrounding incident management and incident response already

exists, so this section contains just a brief overview of the process and a discussion of the tactical

aspects of response. Response is one of the two most important tenets of security (observation

is the other) and a key component of any security strategy. In most instances, incident-related

responses will be triggered by a detective control such as a guard observing a shoplifter, a call

to the help desk, server operations noting the failure of a security process, or antivirus programs

fi nding a Trojan mail attachment. ese responses may also be initiated by external sources such

as the reporting of a product fl aw or third-party notifi cation of suspicious activity or downstream

damage. Nonincident-related responses are usually scheduled but may be triggered by a random

customer inquiry.

Incident Response Procedures

A security incident is defi ned as any adverse event, real or suspected, that violates or threatens to

violate any facility, product, system, or network security provision. Incident response is typically

divided up into progressive stages (phases). e stages are progressive because results from the cur-

rent stage determine whether or not the process will proceed to the next stage. e stages are:

1. Evaluate

2. Contain

3. Resolve

4. Restore

e evaluate stage begins when Transition delivers a security alert to the designated responder.

e fi rst part of the evaluate stage is triage—a quick assessment of the authenticity and severity

of an event based on predefi ned risk or threat criteria. Triage is often facilitated using a short

checklist, fl owchart, or error code lookup procedure. In larger organizations, triage may be car-

ried out by help desk and system management personnel, and the results forwarded to security

operations. e fi rst question triage addresses is the authenticity of the threat; did the alert come

from a valid source, and is the threat real or a hoax? If the alert is invalid or a hoax, the informa-

tion is noted and sent to security operations in an informational message. If the threat is valid,

an incident ticket is created and the alert is forwarded to security operations. e key to success-

ful triage is timeliness; the alert must be processed when it arrives, validated, and forwarded as

quickly as possible. e creation of an incident ticket initiates the formal (structured) incident

response process. In some organizations ticket generation is automated; a program or script uses

the information contained in the alert to create and route the incident ticket. (An incident ticket

is used to track response and resolution time and the actions taken.) Now the real evaluation

work begins. e evaluation process must determine the type and severity of the incident so that

TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 215TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 215 8/18/10 3:11:04 PM8/18/10 3:11:04 PM

216 ◾ Security Strategy: From Requirements to Reality

responses are commensurate with the risks and costs associated with the incident. is varies

considerably with every incident. Gaining privileged access and sharing a password with a co-

worker are both unauthorized access incidents, but the former carries a much higher level of risk.

e evaluation process may involve reviewing video surveillance, audit records, or other sources

of information. Establishing the severity of the incident determines the resolution actions that

will be taken, the time lines for those actions, and the priority given to those actions. e fi nal

task in the evaluate stage is notifi cation. Once an incident has been confi rmed and severity estab-

lished, notifi cations should be issued to all parties responsible for the management or execution

of the response. For example:

e chief security and technology offi cers ◾

e manager(s) responsible for the personnel, facilities, or systems involved ◾

e director of human resources when staff personnel are involved or staff safety is at risk ◾

Legal counsel when legal, regulatory, or contractual requirements are involved ◾

Customer/end-user representatives when customer data are involved ◾

e director of public relations when customer data is involved ◾

Response team members (when severity warrants it) ◾

e process then proceeds to the contain stage. ere isn’t necessarily a hard-and-fast point

where this transition takes place; containment actions may occur during evaluation, especially

when critical assets are involved.

e containment stage is designed to limit the scope and magnitude of an incident, especially

those involving malicious activities. Not all incidents require containment; for example, a security

process that fails is an incident that is already contained to a single device. A product vulnerability

is another example of an incident with a fi xed scope. Malicious code, on the other hand, does not

have a defi ned scope; it can spread very rapidly, incurring massive liabilities and costs as it does.

Containment procedures include actions such as:

Cordoning off a facility or partitioning the network to block the spread of the malicious ◾

activity

Applying additional protections to critical business assets such as locking down the data ◾

center, updating antimalware software, or adding host fi rewall rules

Taking precautionary measures such as transporting valuable assets to another location, ◾

backing up critical business systems, and running diagnostics to verify the operational

integrity of critical systems

Removing compromised systems from service or monitoring them for evidence collection ◾

and investigation purposes

Once the scope of the incident has been contained, the process of repairing or eradicating the

cause of the incident can begin in earnest.

e resolve stage entails the repair or removal of the cause of the incident, for example, remov-

ing a virus from all infected systems and media. In the case of facility or IT systems, the resolve

action may be as simple as revoking someone’s access or as complicated as tracking, arresting, and

prosecuting the attacker. e success of the resolve stage is based on preparedness: having and

maintaining the tools required to repair faulty equipment or software, and eradicating malicious

software or other behaviors. Once the incident has been resolved, the process transitions to the

restore stage or the restorative control. Security groups that have Business Continuity and Disaster

TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 216TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 216 8/18/10 3:11:04 PM8/18/10 3:11:04 PM

SDL and Incident Response ◾ 217

Recovery functions will often consider this a separate control, so catastrophic event recovery can

be included in the control objectives.

e recovery processes restore compromised systems to normal system operations. Recovery

requirements vary depending on the incident. Relatively benign incidents such as port scans only

require verifi cation that all services are still operating properly. Complex attacks involving root

kits, Trojan Horses, or backdoors may require a complete reload of system and application soft-

ware and the restoration of data from backups. e recovery process must include verifi cation of

normal operations.

ere are three additional items related to incident response. e fi rst is escalation. Escalation

procedures defi ne the time frames for additional measures to be taken to ensure incidents are

resolved as quickly as possible. Often in emergency situations the required personnel are not

always available to make corrective changes. Escalation procedures address these shortcomings

and help to reduce the risks and costs associated with prolonged security exposures.

e second item is evidence preservation, which is an important part of incident investigation

and a required component of any legal action. e evidence preservation process should include

the following minimum elements:

An incident investigation log ◾ —All activities related to the incident should be entered into

the log, including interview notes, observations, actions taken, and list of subsequent sus-

picious or abnormal events and the time at which they occurred. e chain of custody of

evidence for all evidence gathered during the investigation should also be maintained in the

log book.

Backup ◾ —A full backup of any system involved in or suspected of being involved in the

incident should be taken as soon as possible after the incident has been confi rmed to preserve

critical log and audit information. Disk imaging is the preferred method for this backup.

Photographs ◾ —Photographs should be taken of the scene, including the system, video

screen contents, and surrounding facilities, in addition to any video surveillance of the scene

captured and preserved.

e third item is follow-up or postmortem review. All incidents should include a review pro-

cess designed to determine root causes and identify what actions can be taken to eliminate fur-

ther occurrences. e review should include response actions (what worked well and what needs

improvement), as well as an analysis of the incident costs (personnel time, lost revenue, hardware

damages, etc.). ese metrics are an important part of your security strategy. e ability to equate

incident response to direct costs provides leverage for security initiatives and helps to demonstrate

the return on investment for those solutions.

It is also important to remember that incident responses will vary depending on the source

of the attack, the value of the asset, the severity of the attack, customer involvement, and so on.

It is wise to build process diagrams and procedures for each instance to ensure the best possible

response.

Automated Responses

Some response procedures can be automated to improve the timeliness and eff ectiveness of

responses. For example, an automated response to a building intrusion alert might activate alarm

bells, turn on lights and surveillance cameras, and switch the video monitor at the guard station

to the aff ected area. A network-generated alert might cause an access rule to be added to a fi rewall

TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 217TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 217 8/18/10 3:11:04 PM8/18/10 3:11:04 PM

218 ◾ Security Strategy: From Requirements to Reality

or router to block the source of a denial of service attack. e possibilities are endless, and so is the

potential for unintended consequences. Automated responses of a retaliatory nature are discour-

aged. Responses that make changes aff ecting a large number of systems are also discouraged. e

best automated responses are those that resolve a specifi c problem and clean up everything that is

left behind (i.e., open fi les, allocated memory, etc.). A common use for an automated response is to

retrieve information related to the alert. e person doing the alert evaluation is going to need it,

so automating the retrieval makes perfect sense. Automation is a key economic principle, and we

encourage the use of automation to improve the eff ectiveness and effi ciency of security processes.

We also encourage careful planning and thorough testing.

Nonincident-Related Response Procedures (Reporting)

Replying to customer inquiries is not commonly thought of as a security response mechanism, but

it is precisely such a mechanism. Mandatory legal, regulatory, and industry compliance report-

ing requirements are directly related to security controls and operations. Requests for compliance

information require a timely response; failing to comply with reporting deadlines can result in

fi nes and other potential sanctions. Customers also expect that the information they request will

be supplied to them in a reasonable time frame; when responses take an inordinate amount of

time, customers become disgruntled. By contrast, when customers can query information directly

(i.e., via a portal), it becomes a brand-enhancing value added.

Reporting as a Response

e Common Collection and Dispatch (CCD) architecture has a reporting component. e

reporting service extracts a subset of information from one or more consolidators to produce vari-

ous types of reports for internal and external customers. For customer-facing reports, the reporting

engines can use a Web interface (i.e., a Customer Portal) to give customers direct access to the

information they seek. e two primary types of reports are:

1. Vertical for management reporting

2. Horizontal for customer reporting

You could look at these reports as summary versus detailed. We advocate a balanced scorecard

(BSC) approach to management reporting because it is an excellent way to report security met-

rics to executive management; the framework supports tangible metrics as well as intangible or

diffi cult-to-monetize goals. BSC makes it possible to highlight strategic progress on risk reduction

without resorting to monetized risk assessments and estimated Annual Loss Calculations (ALC).

Another advantage of the BSC approach is that it communicates strategic security objectives in

terms that align with corporate strategies. is helps improve enterprise strategic planning and

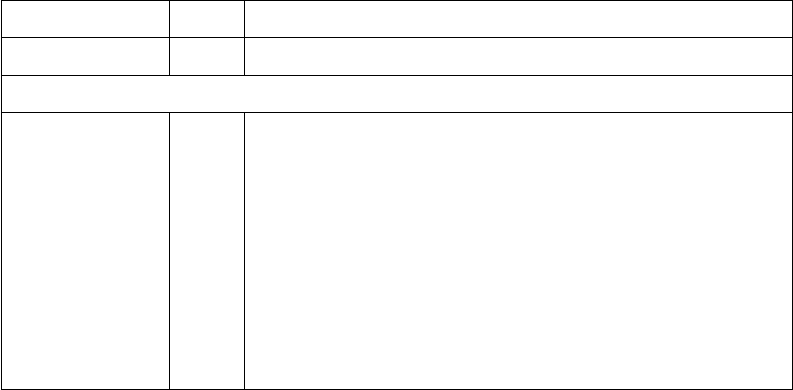

provides management decision support. e report in Figure 11.7 shows the general layout for a

BSC report.

Each section of a BSC report begins with an element from the security strategy, followed by

one or more “perspective” subsections based on the objectives of that element. Each perspective

has specifi c metrics, as well as targets and initiatives that can be reported in percentage of comple-

tion. is provides management with a better understanding of security progress against goals

and of where additional planning and support will be required. e typical interval for balanced

scorecard reporting is quarterly.

TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 218TAF-K11348-10-0301-C011.indd 218 8/18/10 3:11:04 PM8/18/10 3:11:04 PM

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.