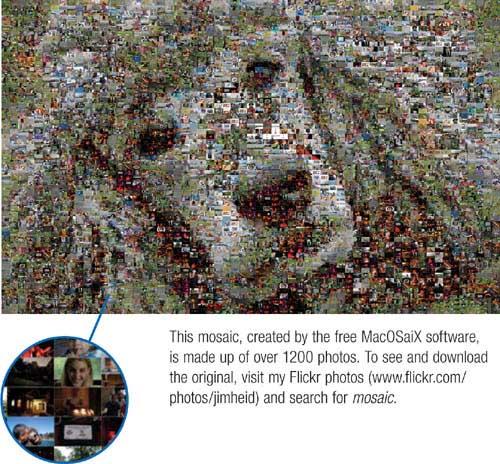

Millions of photographs lead lives of loneliness, trapped in unorganized boxes where they’re never seen. Their digital brethren often share the same fate, exiled to cluttered folders on a hard drive and rarely opened.

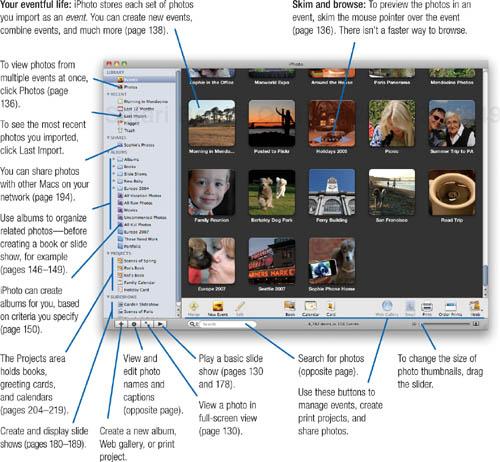

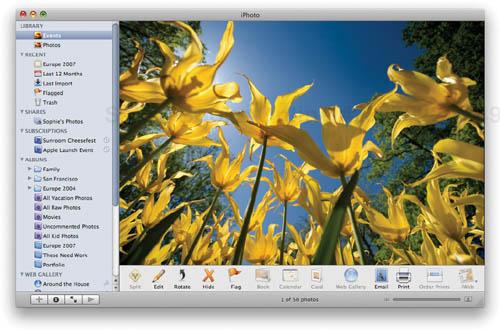

With iPhoto, you can free your photos—and organize, print, and share them, too. iPhoto simplifies the entire process. You begin by importing images from a digital camera, your hard drive, a CD from a photofinisher, or another source. Then you can create albums, organizing the images in whatever order you want. You can even have iPhoto create the albums for you.

Along the way, you might also use iPhoto’s editing features to make your photos look better. And you might use iPhoto’s organization and searching features to help you file and locate images.

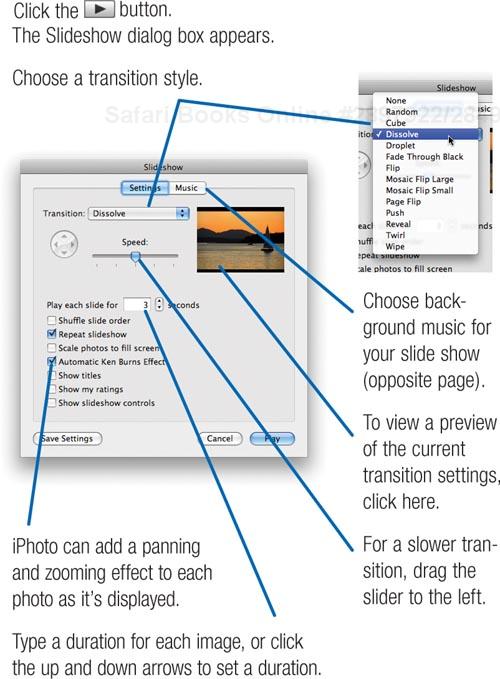

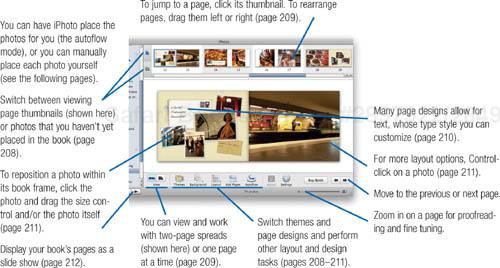

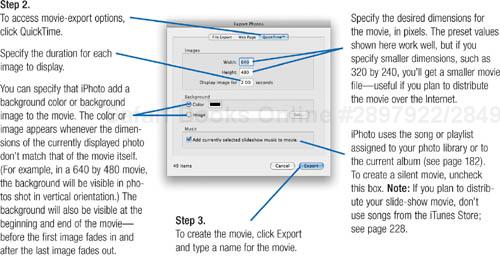

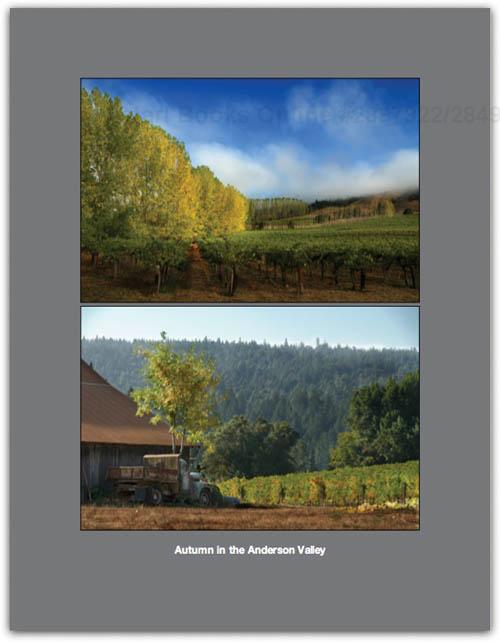

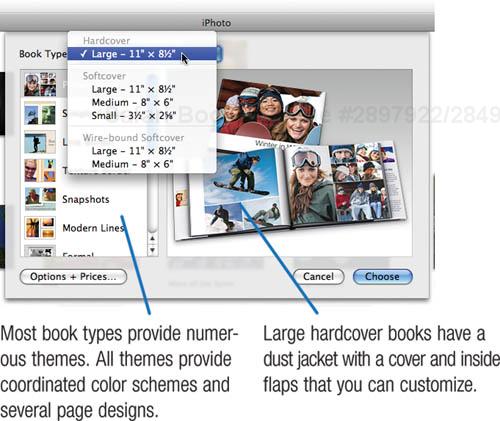

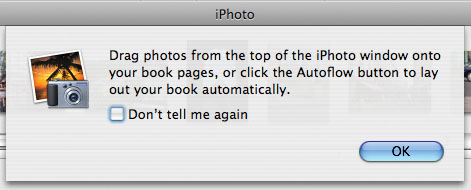

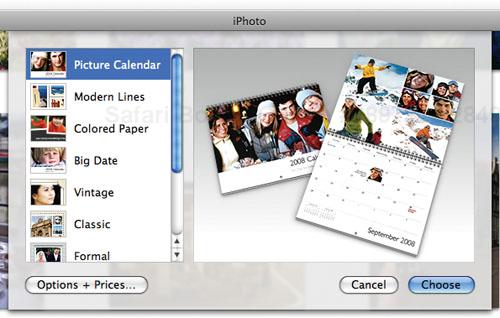

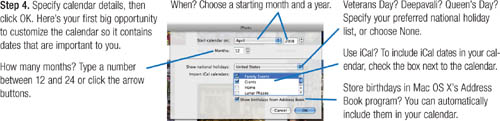

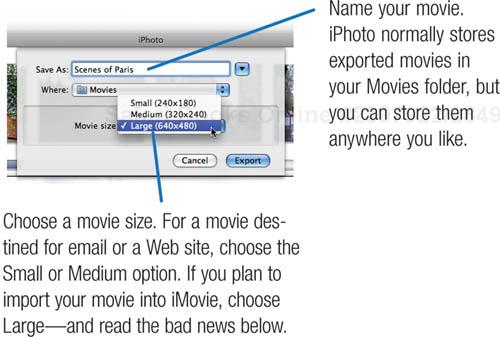

When you’ve finished organizing and editing photos, share them. Order prints or make your own. Design gorgeous photo books, arranging photos on each page and adding captions. Design calendars and greeting cards. Create slide shows, complete with music from iTunes, and then watch them on the Mac’s screen, burn them to DVDs, or transfer them to an iPod or Apple TV.

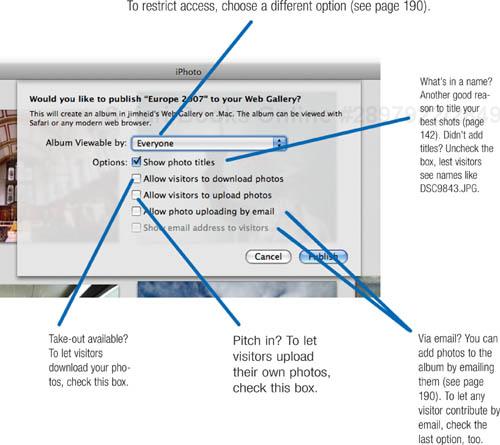

Prefer to share over the Internet? Email photos to friends and family. Have an Apple .Mac account? Create Web photo galleries with iPhoto (page 188), or Web albums with iWeb (page 394).

Welcome to the Photo Liberation Society.

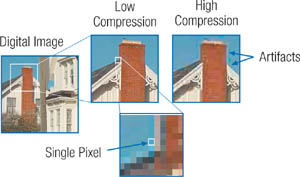

Like the digital audio world and other specialized fields, digital imaging has its own jargon and technical concepts to understand. You can accomplish a lot in iPhoto without having to know these things, but a solid foundation in imaging essentials will help you get more out of iPhoto, your digital camera, and other imaging hardware.

There are two key points to take away from this little lesson. First, although iPhoto works beautifully with digital cameras, it can also accept images that you’ve scanned or received from a photofinisher.

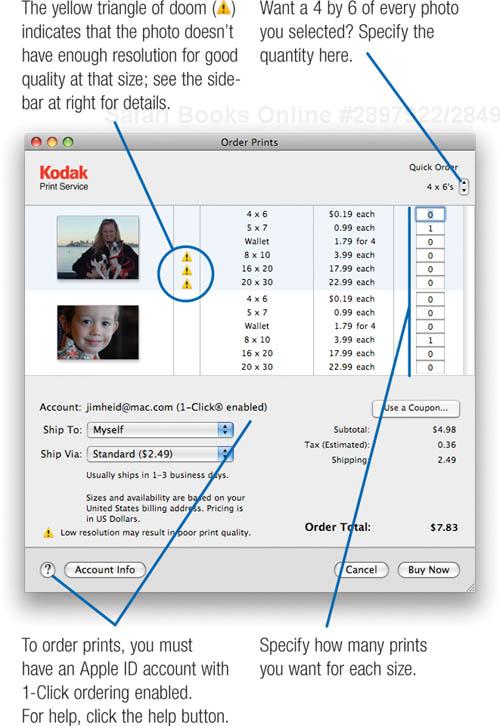

Second, the concept of resolution will arise again and again in your digital imaging endeavors. You’ll want big, high-resolution images for good-quality prints, and small, low-resolution images for convenient emailing to friends and family. As described on page 187, you can use iPhoto to create low-resolution versions of your images.

iPhoto can work with digital images from a variety of sources.

Digital cameras are more plentiful and capable than ever. One key factor that differentiates cameras is resolution: how many pixels of information they store in each image. Even inexpensive digital cameras now provide resolutions of between 6 and 10 megapixels—more than enough to make large prints.

Most digital cameras connect to the Mac’s USB port. Images are usually stored on removable-media cards; you can also transfer images into iPhoto by connecting a media reader to the Mac and inserting the memory card into the reader (page 134).

With a scanner, you can create digital images from photographs and other hard-copy originals.

Scanners also connect via USB, although some high-end models connect via FireWire. Film scanners are a bit pricier, but can scan negatives and slides and deliver great image quality (page 226). Save your scanned images in JPEG format, and then add them to iPhoto by dragging their icons into the iPhoto window (page 135).

For tips on getting high-quality scans, visit www.scantips.com.

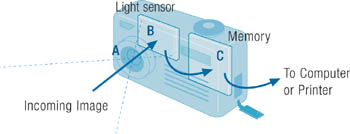

In a digital camera, the image is focused by the lens (A) onto a sensor (B), where tiny, light-sensitive diodes called photosites convert photons into electrons. Those electrical values are converted into digital data and stored by a memory card or other medium (C), from which they can be transferred to a computer or printer.

So you’re the person who’s still shooting film? Good news: for an extra charge, most photofinishers will burn your images on a compact disc in Kodak Picture CD format. You get not only prints and negatives, but also a CD that you can use with the Mac.

To learn more about Picture CD, google the phrase picture cd.

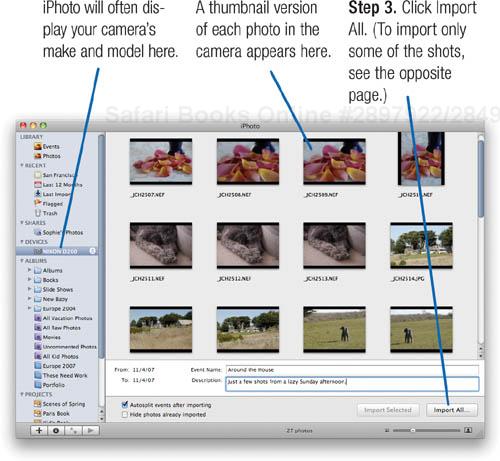

The first step in assembling a digital photo library is to import photos into iPhoto. There are several ways to import photos, but the most common method is to connect your camera to your Mac and transfer the photos using a USB cable. iPhoto can directly import photos from the vast majority of digital cameras.

iPhoto gives you plenty of control over the importing process. You can import every shot in the camera, or you can be selective and import only some. iPhoto stores your photos in the iPhoto Library, located inside your Pictures folder (see page 135).

iPhoto can also import the movie clips that most cameras are capable of taking. If you shot some movie clips along with your photos, iPhoto imports them, too. (For more details on shooting movies with a digital camera, see page 282.)

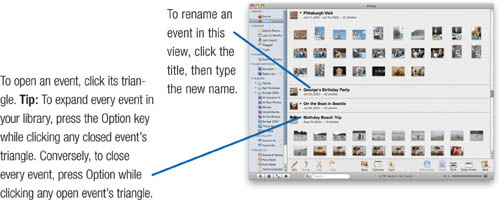

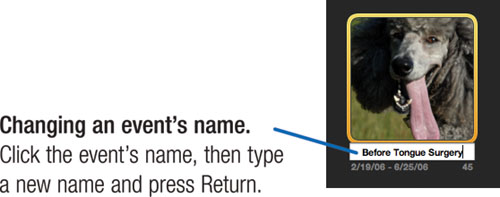

You take photos of the events in your life: vacations, parties, fender benders on the freeway. When you import a set of photos, iPhoto stores them as an event. You can (and should) type a name and description of an event’s photos before importing them. Think of it as the digital equivalent of writing notes on an envelope of prints.

You can manage events—split one event into many, merge multiple events into one, and more—using techniques described on page 138. But that can wait—let’s get those shots into your Mac, shall we?

Connect your camera to one of your Mac’s USB ports (the port on the keyboard is particularly convenient) and turn the camera on. When iPhoto recognizes your camera, it displays the Import panel.

Tip

If your camera has a battery-saving sleep mode, adjust it so that the camera won’t drift into slumber while your photos are still importing.

Type a name that best describes this set of photos. You can also type a brief description if you like.

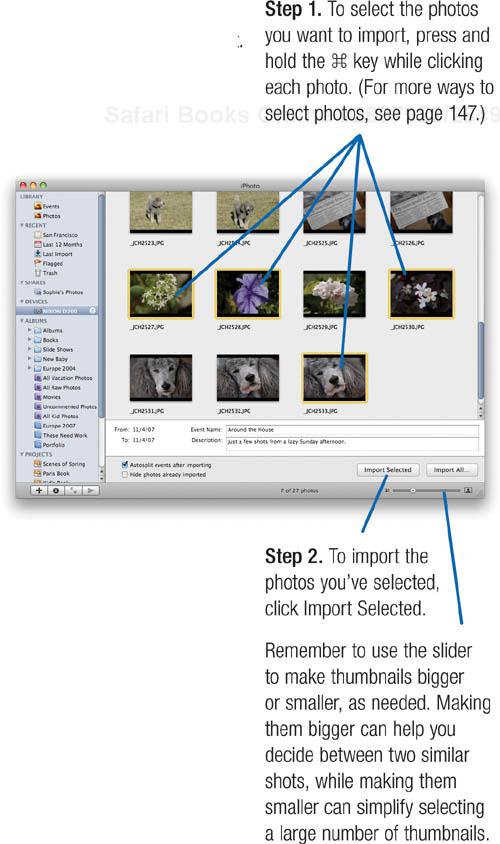

As you look over the thumbnails in the Import panel, you see some shots that you just know you aren’t going to want. So why waste time importing them to begin with? You can be selective and import only those shots you want.

When iPhoto finishes importing, it displays a message asking if you’d like to keep or delete the original photos from the camera.

I recommend clicking Keep Originals. It’s best to erase your memory card using your camera’s controls. Specifically, use your camera’s “format” command, not its “delete all” function.

What’s the difference? Formatting the card not only deletes photos, it creates a brand-new directory—that digital table of contents that’s so critical to any storage device. When you simply “delete all,” the camera wipes the shots, but doesn’t create a fresh directory. This increases the odds that little glitches of fate could cause directory corruption that leads to lost photos.

So click Keep Originals, then use your camera’s menu controls to reformat the card.

What happens after iPhoto imports a set of photos? That’s up to you. Admire your shots. Start filing and organizing them. Email a few favorites to a friend.

If you’re like me, you’ll want to check out your shots right away. A couple of clicks gives you a full-screen slide show, complete with music—perfect when you have a circle of eager friends and family watching over your shoulder. Or be selective: display thumbnails of your new photos, then take a close-up look at the best of the bunch.

Some housekeeping may await, too. Delete the shots you don’t want. Rotate vertically oriented shots, if necessary. As you tidy up, you’ll probably start getting ideas for sharing the photos. Email, prints, books, calendars, cards, Web galleries, DVDs, YouTube: if you like to share images, this is a great time to be alive.

And along the way, you’ll want to celebrate your inner librarian. Organize your photo library with events, titles, captions, keywords, and albums. Trust me: you’ll accumulate thousands of photos in no time. A few simple steps will make them easier to find.

But filing can wait. We have some fresh photos to explore.

Start by clicking the Last Import item in the Library area. This is the fastest way to access the most recent set of shots.

Selective viewing. Adjust the size of the photo thumbnails to your liking: jump down to the lower-right corner and use the size slider.

To magnify a photo so that it fills the iPhoto window, double-click its thumbnail, or select the photo and press the spacebar. Tip: Maximize your viewing area: choose Window > Zoom or click the green zoom button in the upper-left corner.

To return to thumbnails, click the mouse or press the Esc key.

Full-screen variation. To fill the entire screen with a photo, click ![]() . To return to the thumbnails, double-click the mouse or press Esc. (For more about full-screen view, see page 168.)

. To return to the thumbnails, double-click the mouse or press Esc. (For more about full-screen view, see page 168.)

Tip

To move to the next or previous photo in either magnified view, press your keyboard’s right- or left-arrow key.

Instant slide show. To screen your photos with more style, display a slide show. Hold down the Option key on your keyboard and click ![]() . To stop the slide show, click the mouse or press Esc.

. To stop the slide show, click the mouse or press Esc.

(Pressing the Option key bypasses a step: choosing a soundtrack song. When you want to take time for that extra step, don’t press Option. See page 179 for soundtrack details, and pages 178–183 to learn all about slide shows.)

Some cameras automatically rotate photos taken in vertical orientation. If yours doesn’t, the job is yours. Select the photo or photos and then click the Rotate button or press ![]() (to rotate counterclockwise). To rotate clockwise, Option-click the Rotate button or press

(to rotate counterclockwise). To rotate clockwise, Option-click the Rotate button or press ![]() -Option-R. You can also rotate photos while viewing a slide show; see page 179.

-Option-R. You can also rotate photos while viewing a slide show; see page 179.

Tip

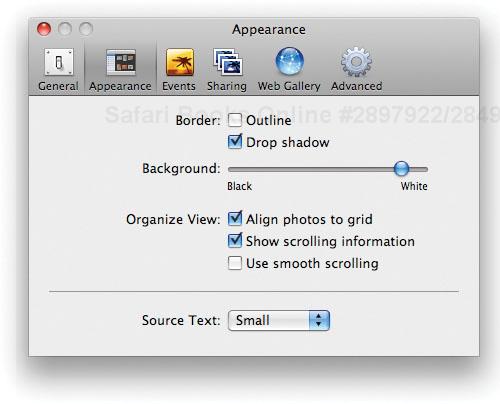

If you find yourself doing a lot of clockwise rotation, you can tweak iPhoto preferences to eliminate having to press Option while clicking Rotate. Choose iPhoto > Preferences, click the General button, then click the leftmost Rotate option:

Now you can rotate clockwise by simply clicking the Rotate button.

See a photo that you know you don’t want to keep? Trash it. To delete a photo, select it (click it once), then press the Delete key. You can also delete a photo by dragging it to the Trash on the left side of the iPhoto window.

When you put a photo in the Trash, iPhoto doesn’t actually erase the photo from your hard drive; that doesn’t happen until you choose Empty Trash from the iPhoto menu. If you change your mind about deleting a photo, click the Trash item in the library list, select the photo you want to keep, and choose Photos > Restore to Photo Library (keyboard shortcut: ![]() -Delete.)

-Delete.)

Most people import photos directly from a camera using the technique I described on the previous pages. But you have more than one way to get photos into iPhoto.

A media reader is a great way to import photos from a camera’s memory card. Plug the reader into your Mac, then insert the memory card into the reader. Because you aren’t using your camera to transfer photos, its battery charge will last longer.

Be sure to get a reader that supports the type of memory cards your camera uses. Or get a multi-format reader that supports several types of memory cards. And look for a reader that connects to the Mac’s FireWire jack or to its USB 2.0 jack. FireWire and USB 2.0 readers transfer images much faster than the older, USB 1.0 interface.

You can also import images by dragging their icons into the iPhoto window. If you’ve scanned a batch of images, you can use this technique to bring them into iPhoto. You can also use this technique to save photos that people email to you or that you find on Web sites.

Here’s the photo-importing technique I use most often.

Connect the media reader to your Mac.

Be sure your camera’s power is off, then remove the memory card from the camera and insert it into the reader. iPhoto recognizes the card and displays the Import panel shown on page 130.

Type a name and description for the photos you’re about to import, then import all or some of the photos, as described on the previous pages.

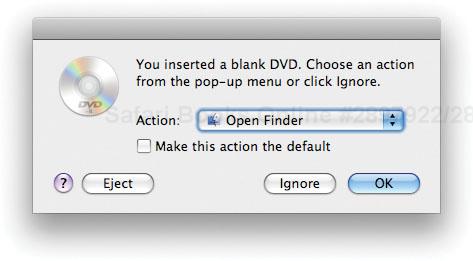

After iPhoto has imported the photos, click the Eject button next to the memory card’s name in the Devices list. Finally, remove the memory card from the reader, return the card to your camera, and then erase the card.

Laptop Media Readers. You can buy a media reader that plugs into the PC Card slot of a PowerBook. If you’re traveling with a PowerBook, a PC Card-based reader is a compact alternative to a FireWire or USB reader.

Media readers are also available for the ExpressCard/34 slot provided by the MacBook Pro laptops, too. Unfortunately, the ExpressCard/34 slot is too small to accommodate a Compact Flash card, requiring you to use an awkward adaptor. If you use Compact Flash cards and own a MacBook Pro, you’re probably better off with an external FireWire or USB 2.0 reader. Look at it this way: at least your external modem will have company in your briefcase.

To import an entire folder full of images, drag the folder to the Photos item or into the photo area.

iPhoto gives the new event the same name as the folder from which its images came. You can rename the event using the techniques described on page 138.

To import only some images, select their icons and then drag them to the Photos item or into the iPhoto window.

A friend has emailed some photos to you, and you want to add them to your iPhoto library. If you’re using Mail, the email program included with Mac OS X, simply drag the photos from the email message into the iPhoto window. If the email message contains several photos, Shift-click on each one to select them all before dragging.

If you use Microsoft Entourage, your job is a bit more difficult. First, save the photos on your Mac’s desktop. Next, drag them into the iPhoto window as shown at left. Finally, delete the photos from your desktop.

To save a photo that’s on a Web page, just drag the photo from your Web browser into the iPhoto window. In Apple’s Safari browser, you can also Control-click on a photo and choose Add Image to iPhoto Library from the shortcut menu.

iPhoto can also import images saved on a Kodak PhotoCD or Picture CD. (PhotoCD is an older format that you aren’t likely to see too often. Picture CD is a newer format that most photo finishers use.)

Picture CD. Choose Import to Library from iPhoto’s File menu, locate the Picture CD, and then locate and double-click the folder named Pictures. Finally, click the Import button. Or, use the Finder to open the Pictures folder on the CD and then drag images into iPhoto’s window.

PhotoCD. Simply insert the PhotoCD in your Mac’s optical drive. iPhoto launches and displays its Import panel. Type a name and description for the photos, then import some or all of the photos, as described on the previous pages.

iPhoto gives you plenty of control over the importing process. Do you want iPhoto to automatically split up the photos into numerous events? If so, what time interval do you want to use?

If you’re adding photos by dragging them from folders on your hard drive, where do you want iPhoto to store the photos?

If questions like these burn in your brain, your fire extinguisher has just arrived. Otherwise, feel free to skip on. You can always return here when the embers begin to glow.

You wisely took my page 129 advice and told iPhoto to not delete photos from your camera after an import (see page 129). But you forgot to erase the card before shooting another two-dozen shots.

No problem. When you connect your camera and switch to iPhoto’s Import panel, check the box labeled Hide Photos Already Imported. Photos you’ve already imported will disappear from the Import panel, making it easy to import some or all of the new shots.

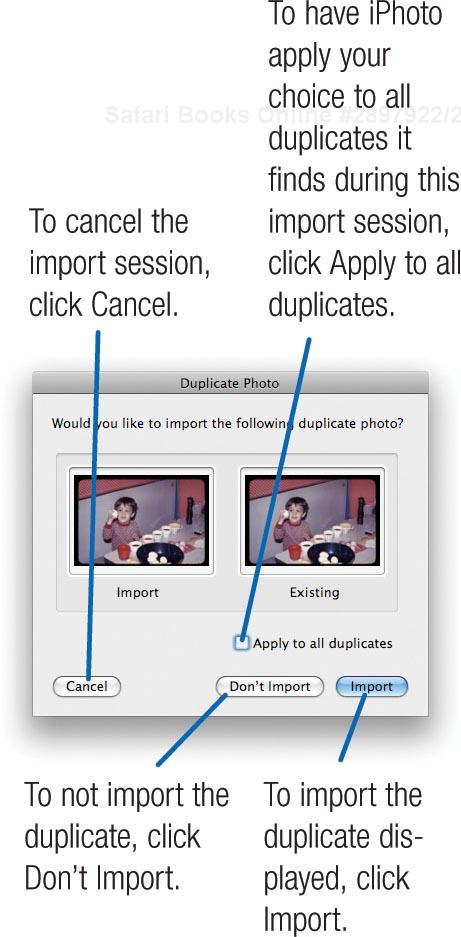

Even if you forget to check the aforementioned box, iPhoto has you covered. If you try to import a photo that already exists in your library, iPhoto asks if you really want to import the duplicate.

As I mentioned on page 128, iPhoto stores imported shots as events. When you import photos from a camera, iPhoto automatically splits them into events (unless you uncheck the Autosplit Events After Importing box in the Import pane).

Normally, iPhoto considers one day’s worth of photos to represent an event. For example, if you import some shots taken over a weekend, you’ll have two events: Saturday’s photos and Sunday’s.

Using the Preferences command, you can change the interval of time iPhoto uses when splitting photos into events. Choose iPhoto > Preferences, then click Events. You have three additional choices.

One event per day. iPhoto creates a new event for each 24-hour period. Take a week’s vacation, import all your shots, and you’ll have seven events.

This is an ideal option for vacations and similar getaways.

Two-hour gaps. iPhoto creates a new event every two hours. Say you do a day’s worth of shooting: a sunrise hike at 6:00 a.m., a brunch with friends at 10:00 a.m., and a party at night. Import the shots, and iPhoto will create three events.

When you shoot a lot of shots throughout a day, this option can help corral them into manageable (and related) chunks. Surviving the busy day is your problem.

Eight-hour gaps. iPhoto creates a new event every eight hours. In the busy-day example above, you’d end up with two events: the first containing the hike and brunch photos, and the second containing the party pix.

Before you import a set of photos, think about what kind of time intervals the photos represent, then consider tweaking the interval preference to match.

Or don’t bother. You’re never locked into the way iPhoto divvies up your life. You can move photos between events in whatever way you like, and you can have iPhoto autosplit events for you after you’ve imported photos. Pages 138–139 have all the details.

When you import photos from the Finder—by dragging their icons into iPhoto, as described on the previous page—iPhoto does not split the photos into events. That makes sense when you think about it: if you’re importing a dozen scanned images of photos that are decades old, how would iPhoto know how to divvy them up?

But in some circumstances, you might want iPhoto to automatically split photos imported from the Finder. For example, maybe you’re about to import a CD’s worth of digital photos that a friend burned for you.

For times like these, return to the Events portion of the Preferences dialog box, and check the box labeled Imported Items From Finder.

Since the dawn of time—well, since the dawn of version 1.0—iPhoto has always stored images in the iPhoto Library. Generally, that’s exactly what you want: when you copy photos from a camera or memory card, you want them stashed safely in your iPhoto Library.

But under some circumstances, iPhoto’s “do things my way” approach to organization can work against you. When you add photos that are already stored on your hard drive—for example, images that you’ve scanned and saved—iPhoto makes additional copies in the iPhoto Library.

After adding photos to your Library that are already on your hard drive, you need to delete the originals. That isn’t exactly a sweat-breaking chore, but it does take time. And you might prefer to stick with your existing filing system.

You have the option to not copy image files to the iPhoto Library. If you have a large library of meticulously filed scanned images on your hard drive, you might want to take advantage of this option. You won’t have duplicate photos to delete, and you won’t have to change the filing system you’ve developed for your scanned images.

To activate this option, choose iPhoto > Preferences, click the Advanced button, and then uncheck the box labeled Copy Items to the iPhoto Library.

From now on, when you add items from your hard drive to your iPhoto library, iPhoto simply creates aliases for each item. (In Mac OS parlance, an alias is a small file that simply points to an existing file.) If you edit an image, iPhoto stores the edited version in your iPhoto Library.

And by the way, unchecking this option does not change how iPhoto stores photos that you’re importing from a camera or media reader. Photos that you import from a location other than a hard drive are always stored in your iPhoto Library.

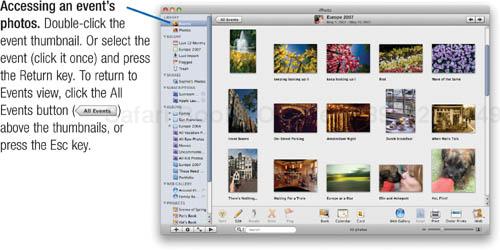

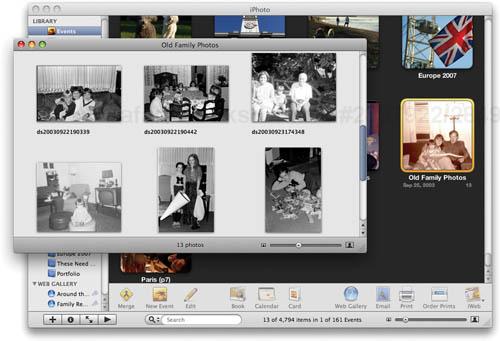

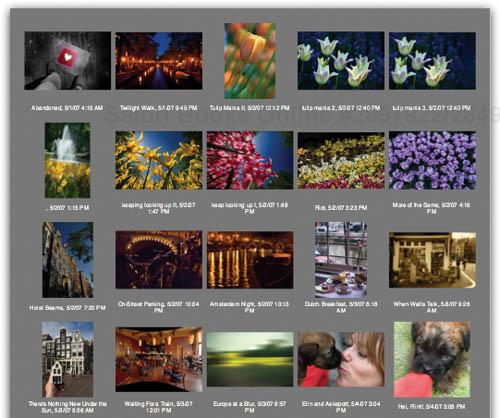

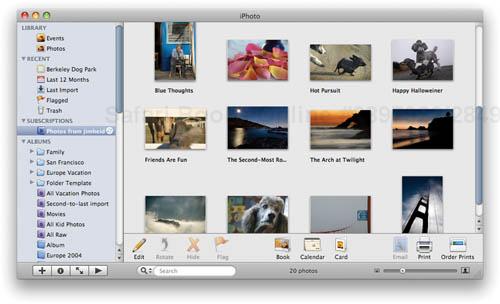

Unlike any shoebox, iPhoto gives you several ways to browse and explore your photo library. Use Events view to get an at-a-glance look at your library. Forget which photos are in an event? Move your mouse pointer across the event thumbnail, and its photos flash before your eyes.

Events view is the most convenient way to work with your photo library, and chances are it’s the view you’ll use most of the time. But there’s another way to see your shots. Click the Photos item in the Library list, and iPhoto displays your events in a different format—one that you may find useful for some browsing and photo-management tasks.

(If you’re an iPhoto veteran, you’ll recognize the Photos view—it’s similar to the “film rolls” view provided by earlier versions of iPhoto.)

In both views, iPhoto provides little conveniences that help you home in on the photos you seek. For example, as you scroll the iPhoto window, semi-transparent scroll guides appear that show the date and title of each event.

Knowing the basics of photo browsing is important—the faster you can get around in your photo library, the greater the chances that you’ll explore and enjoy your photos.

Here’s an overview of the ways iPhoto lets you browse.

Here are the basic techniques you’ll use when working with events.

Skimming thumbnails. Pass your mouse pointer over the event without clicking. Tip: You can also skim by combining the mouse and keyboard: point to an event, then press the left- or right-arrow keys. I like to use this technique when an event has a lot of photos in it, or when I’ve used the size slider to make the event thumbnails small.

Tips

Want to browse using just the keyboard? First, be sure the mouse pointer isn’t over an event. Then, use the arrow keys to select an event. Press Return to see its thumbnails. Press Esc to return to Events view, then arrow-key your way to a different event and repeat.

When you’re viewing an event’s photos, you can jump to the previous or next event by clicking the arrows in the upper-right corner of the iPhoto window.

Setting the key photo. Each event is represented by one photo, called the key photo or the poster photo. You can change the key photo to one that best represents the event. Skim across the event, and when you see the photo that you want to be the new key photo, press the spacebar. You can also Control-click on the photo and choose Make Key Photo from the shortcut menu. (This latter technique also works in Photos view.)

Detail view. Sometimes, you need to view the photos of more than one event at once. Maybe you’re organizing some recent imports and you want to work on multiple events at the same time—to move some photos from one event to another, for example.

To open more than one event, select each event (click it once), then double-click one of the selected events or press Return. iPhoto opens each selected event.

To return to Events view, click All Events or press Esc.

Separate event window. You can also open an event in its own window: select the event, then choose Events > Open Event in Separate Window. A new window opens containing the event’s photos.

The separate window is a great way to focus in on the shots in one event while retaining quick access to the rest of your library. The window provides its own size slider for adjusting the size of photo thumbnails. You can even zoom the separate window to fill your screen or a second display, if your Mac has one: choose Window > Zoom.

The following pages describe more uses for the separate event window.

Anxious to start having fun with your photos? Go ahead and skip to page 146, where you can learn about creating photo albums and much more.

Eventually, you’ll want to learn about the power tools that iPhoto provides for managing photos and events. These maneuvers can help you organize your iPhoto Library and make it easier to corral photos prior to sharing them.

A lot of photos fall into that middle ground between bad and beautiful: not awful enough to trash, not good enough to look at all the time. iPhoto lets you hide those mediocre shots to tidy up an event, but bring them back whenever you like.

Hiding photos is also a good strategy when you’ve taken several nearly identical shots—some portraits, each with a different smile. Pick the best, hide the rest.

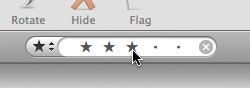

To hide a photo, select it and click the Hide button (or press ![]() -L). The photo vanishes, and adjacent photos snuggle in to fill the void.

-L). The photo vanishes, and adjacent photos snuggle in to fill the void.

Bringing them back. When you’re viewing an event, iPhoto lets you know if any of its photos are hidden.

To hide the photos again, click the message again. To unhide a photo, select it and click Unhide or press ![]() -L.

-L.

You can split one event into two. Say you have an event containing a hundred shots from an afternoon bike ride and an evening dinner. You may prefer to split the event into two separate, more manageable ones.

To split an event, open it to display its thumbnails. Then, select the photos you want to split off (the dinner shots, for example), and click the Split button. Finally, name the new event.

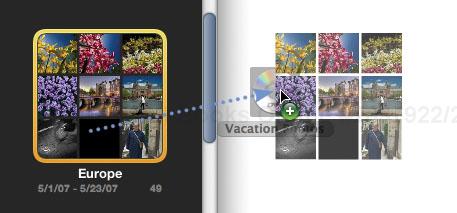

Merging events. You can also combine two or more events into one. Maybe you fired off some shots at a party, imported them so everyone could see, then took some more. You want all the party shots to be in one event. Easy: drag one event to the other.

You can also merge more than two events: Shift-click or ![]() -click on each event, then drag them to another event. Or select all the events, then click the Merge button.

-click on each event, then drag them to another event. Or select all the events, then click the Merge button.

Sometimes, your life as an event planner requires you to move individual photos between events. Maybe you want to fine-tune the way iPhoto autosplit an event. Or maybe a travel companion emailed you some shots that she took, and you want to add a few of them to your vacation event.

There are moving plans aplenty.

Dragging. Open the events in detail view: select them and double-click one of them (page 137). Now drag thumbnails from one event to another. To give yourself more dragging room, zoom the iPhoto window (Window > Zoom) and make the thumbnails smaller (drag the size slider).

The separate event window, described on page 137, can be handy when dragging photos between events, especially if the events aren’t near each other in your library.

Cut and paste. Select the photos you want to move, and choose Edit > Cut. Select the event where you want them, then choose Edit > Paste. When dragging seems like too much work—too many photos, too many events—this is an efficient alternative.

Flagging. This can be the most powerful way to move photos, and it’s described at right.

You can create a new, empty event and then add photos to it. Be sure no events are selected, then choose Events > Create Event.

(You can also use Create Event to merge events or split photos off into their own event: Select the events or individual photos, then choose Create Event.)

Flagging is like attaching a sticky note to a photo. Trying to decide which shots to add to a book? Flag the best candidates, and you can return to them in a flash.

To flag a photo, select it and click the Flag button or press ![]() -period. A flag badge appears on the photo’s thumbnail.

-period. A flag badge appears on the photo’s thumbnail.

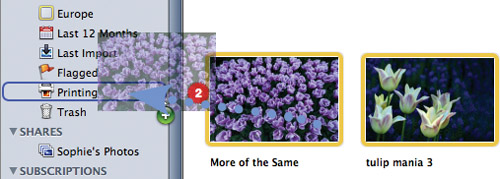

You can flag multiple photos at once–select them first, then click Flag–and you can flag as many shots as you like. To quickly see the shots you’ve flagged, click the flagged item in the Recent area of the Library list.

You’ve flagged some shots. Then what?

Move them to an existing event. After flagging the shots, return to Events view. Select the event where you want to move the photos, then choose Events > Add Flagged Photos to Selected Event. If you need to move some shots that are scattered throughout your library, this is the best way to do it.

Move them to a new event. To move flagged photos into a new event of their own, choose Events > Create Event From Flagged Photos. Keep in mind, though, that iPhoto will move those photos from their original events.

Work with them. Select the Flagged item in the Library area. The flagged shots lurk there, ready to be edited, shared—whatever you like.

Lower the flags. Done working with some flagged photos? Here’s the easiest way to unflag them all: click the little number next to the Flagged item in the Library area.

Normally, when you double-click an event thumbnail, you see the event’s photos. With this trick, you can double-click to magnify whichever photo is visible under the mouse pointer. Skim across an event, see a photo you want to magnify, and double click.

Choose Preferences > iPhoto, click Events, then choose the Magnifies Photo option.

You can also tweak iPhoto so that a double click opens a photo in edit view (page 152)—the way earlier iPhoto versions worked. Choose iPhoto > Preferences, click General, and choose the Edits Photo option.

iPhoto forces some organization on you by storing each set of imported images as a separate event. Even if you never use iPhoto’s other organizational features, you’re still ahead of the old shoebox photo-filing system: you will always be able to view your photos in chronological order.

But don’t stop there. Take the time to assign titles and descriptions to your favorite shots. By performing these and other housekeeping tasks, you can make photos easier to find and keep your library well organized.

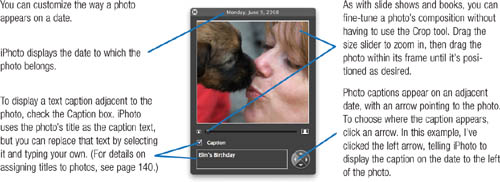

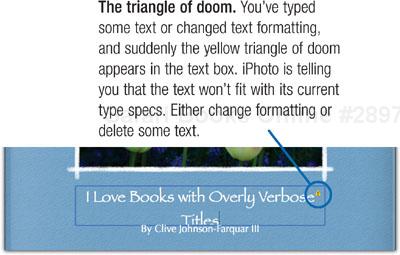

Titles are names or brief descriptions that you assign to photos and events: Party Photos, Mary at the Beach, and so on. iPhoto can use these titles as captions for its Web photo albums and books. Using the View menu, you can have iPhoto display titles below each thumbnail image. You can also search for photos by typing title or description text in the Search box (page 142a).

There’s one more benefit to assigning titles to photos: when you’re working in other iLife programs, you can search for a photo by typing part of its title in the photo media browser’s Search box.

Of course, you don’t have to type titles and descriptions for every photo in your library. But for the ones you plan to share in some way—or that you’ll want to search for later—it’s time well spent.

When you want to give photos titles and descriptions, turn to the Information pane. To display the Information pane, click the ![]() button.

button.

On a roll. Want to quickly title (or describe) one photo after another? Press ![]() -] after typing a title or description, and iPhoto selects the next photo and highlights its title or description field so you can immediately begin typing. To move to the previous photo, press

-] after typing a title or description, and iPhoto selects the next photo and highlights its title or description field so you can immediately begin typing. To move to the previous photo, press ![]() -[. And to keep your hands on the keyboard, press Tab and Shift-Tab to jump from one field to the next in the Information pane.

-[. And to keep your hands on the keyboard, press Tab and Shift-Tab to jump from one field to the next in the Information pane.

Check your spelling. Want to check the spelling of your titles and descriptions? Select the text you want to proofread, then choose Edit > Spelling > Check Spelling. Or select the text you want to proofread and press ![]() -;.

-;.

Many at once. To change information for many photos at once, select them and choose Photos > Batch Change (see the opposite page). If you’re like me and are often too lazy to assign titles and descriptions to individual photos, this can be a good compromise: assign a phrase to a set of related photos, and you can search for that phrase later.

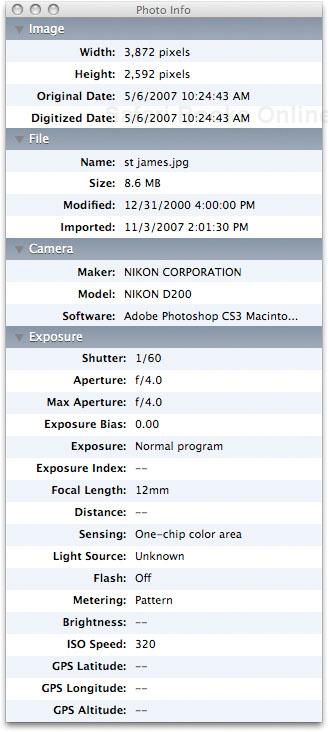

The Information pane is a great place to view and change all kinds of details: a photo’s title, its description, the date and time it was taken, and more.

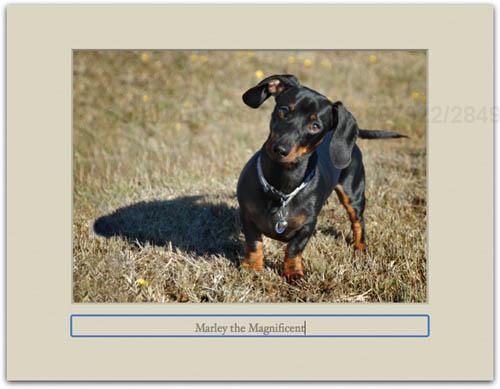

But there’s another way to edit photo information, and it’s often more convenient than opening the Information pane. Simply click the title beneath a photo’s thumbnail, and start typing:

(If you don’t see titles beneath your photo thumbnails, choose View > Titles.)

The keyboard-shortcut tips described at lower left work here, too: type a title, and press ![]() -] to jump directly to the title field of the next photo. Or move the next and previous photo by pressing Tab and Shift-Tab.

-] to jump directly to the title field of the next photo. Or move the next and previous photo by pressing Tab and Shift-Tab.

As the following pages describe, you can also assign keywords and ratings by working directly beneath photo thumbnails. You can’t, however, type a description or change a photo’s date or time. For those tasks, turn to the Information pane.

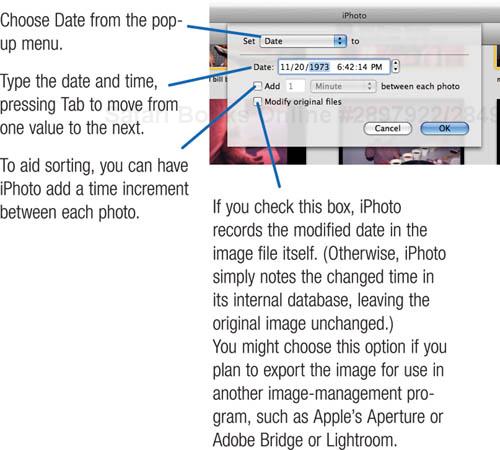

Time is important. The date stored along with a photo determines how iPhoto sorts the photo. Accurate dates also simplify searching and organizing your library.

All digital cameras store date and time information along with the image (see the sidebar on page 145). But what if your camera’s clock is off? Maybe you forgot to adjust its time zone when you flew to Hawaii.

Or maybe you’ve scanned some old family photos and you want their dates to reflect when they were taken, not scanned. That Aunt Mary photo is from 1960, not 2008.

Time travel is easy in iPhoto. You can edit the date of an event, a selection of images, or just one photo. The steps differ depending on what you want to change.

An event. Select the event, choose Photos > Adjust Date & Time.

More than one photo. Select the photos, and choose Photos > Batch Change.

Just one photo. Select the photo, open the Information panel, and type new dates and times.

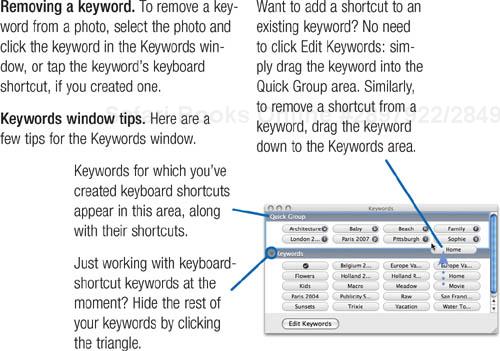

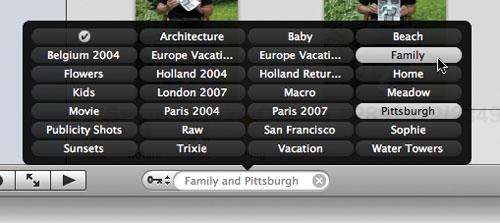

Chances are that many of your photos fall into specific categories: baby photos, scenic shots, and so on. By creating and assigning keywords, you make related images easier to find.

Keywords are labels useful for categorizing and locating all the photos of a given kind: vacation shots, baby pictures, mug shots, you name it.

iPhoto has several predefined keywords that cover common categories. But you can replace the existing ones to cover the kinds of photos you take, and you can add as many new keywords as you like.

You can assign multiple keywords to a single image. For example, if you have a Beach keyword, a Dog keyword, and a Summer keyword, you assign all three to a photo of your dog taken at the beach in July.

Keywords are one way to categorize your photos; ratings are another. You can assign a rating of from one to five stars to a photo—rank your favorites for quick searching, or mark the stinkers for future deletion.

As with many iPhoto housekeeping tasks, assigning keywords and ratings is entirely optional. But if you take the time, you can use iPhoto’s search and Smart Albums features to quickly locate and collect photos that meet specific criteria.

Choose Window > Show Keywords (

-K).

-K).Click the Edit Keywords button.

Edit keywords as shown below, then click OK.

Displaying keywords. To have iPhoto display keywords beneath photo thumbnails, choose View > Keywords.

Creating a keyword directly. When viewing keywords beneath thumbnails, you can create a new keyword by simply typing it beneath a photo thumbnail. Point beneath the thumbnail until the text add keywords appears.

You have a few ways to assign keywords.

The keywords window. Choose Window > Show Keywords. Select the photo(s), then click one or more keywords.

The keyboard. If you assigned a keyboard shortcut to the keyword, reap your reward now. Select the photo(s), and tap the shortcut key.

If you have to assign various keywords to a set of photos, combine shortcut keys with the arrow keys. Select a photo, tap a key, tap an arrow key to move to a new photo, tap a key. There’s never been a faster way to assign keywords in iPhoto.

Directly beneath the thumbnail. See the tip on the opposite page, at lower left.

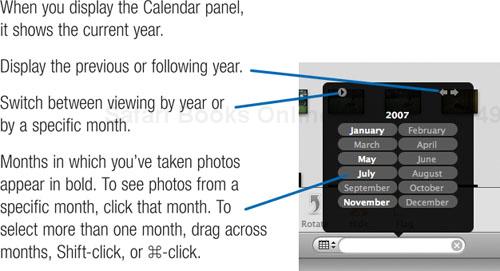

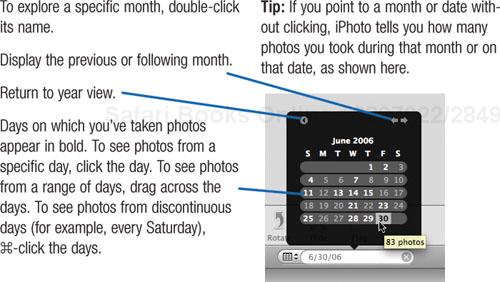

Browsing is fun, but not when you’re looking for something specific. When you’re on the hunt, you want help: directions from your car’s navigation system, a directory in a shopping mall, or a search feature in your digital photography program.

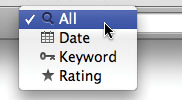

iPhoto lets you search in several ways. For quick searches, jump down to the Search box and start typing. As you type, iPhoto narrows down the photos it displays—much as iTunes does during song searches. The more time you spend giving titles and descriptions to your best shots (page 140), the better the search feature works.

Next to the Search box, a pop-up menu lets you search in more specific ways. Look for photos taken on certain dates. Or photos with a four-star rating, or with certain keywords.

And when your searching needs are very specific—show me the four-star photos of the dog taken before noon at the beach with my Nikon camera during the month of July—iPhoto can accommodate. Just create a smart album (page 150).

So go ahead and browse when you want to relive random memories. But when you’re on a mission? Search.

No matter what kind of search you perform, keep this in mind: iPhoto searches whatever item you’ve selected in the Library list. If you want to search your entire library, be sure to click Events or Photos. To search the last year’s worth of photos, click Last 12 Months. To search a specific album, click the album. You get it.

Searching by rating. From the Search box pop-up menu, choose Rating. Click the dots to specify a minimum number of stars a photo must have.

Note

Higher-rated photos also appear: if you click three stars, four- and five-star photos also appear. To find just three-star photos, for example, create a smart album.

Searching by keyword. From the Search box pop-up menu, choose Keyword, then click one or more keywords. (For tips on keyword searching, see the opposite page.)

Searching by date. From the Search box popup menu, choose Date, then specify a date or range of dates (see the opposite page).

Even if you never give a photo a title, description, or keywords, you can always search by date, since your camera records the date and time when you take a photo.

And remember, you can use iPhoto to adjust the dates of your photos to make date searches as accurate as possible (page 141).

Getting photos back from a lab is always exciting, but what’s really fun is creating a photo album that turns a collection of photos into a story.

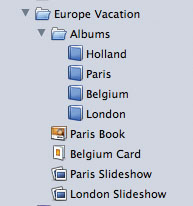

An iPhoto album contains a series of photographs sequenced in an order that helps tell a story or document an event. Creating an album is often the first step in sharing a set of photos. For example, before creating a slide show or book, you’ll usually want to create an album containing the photos you want to use.

Creating albums in iPhoto is a simple matter of dragging thumbnail images. You can add and remove photos to and from albums at any time, and you can sequence the photos in whatever order you like. You can even include the same photo in many different albums.

The photos in an album might be from one event, or from a dozen different events. Just as an iTunes playlist lets you create your own music compilations, an iPhoto album lets you create your own image compilations.

You don’t have to create albums for every set of photos you import. But when you want to combine photos from different events, particularly when you’re planning to share the photos in some way, albums are the answer.

You don’t have to create an album in order to share photos: you can create slide shows, books, calendars, and Web pages by simply selecting photos in your library, and then using the appropriate button or command.

This has always been true in iPhoto, but it’s more applicable than ever in iPhoto ’08. By hiding less-than-perfect photos (page 138), you can “edit” an event to contain only those photos you want to use in a project.

Still, when you’re about to create a photo project of some kind, it’s better to create an album first. Albums give you the ability to change the sequence of photos. You can resequence photos while creating slide shows, books, and the like, but creating these items is easier when you start with the photos that are in roughly the final order that you plan to use.

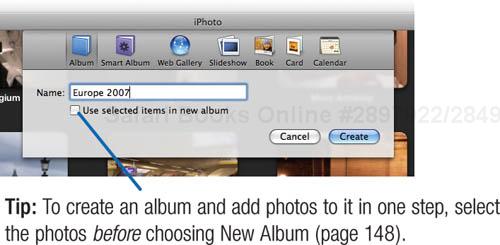

You can create an album and add images to it in one step. Select one or more images and choose File > New Album. In the dialog box that appears, check the box labeled Use Selected Items in New Album. Or select some photos, then choose File > New Album from Selection (Shift-![]() -N).

-N).

You can also drag the images into a blank spot of the Library area. When you use this technique, iPhoto gives the new album a generic name, such as untitled album. To rename the album, double-click its name and type a new name.

If you have photos on a storage device—your hard drive, a Picture CD, or a digital camera’s memory card—you can import them into iPhoto and create an album in one fell swoop.

Simply drag the photos from the Finder into a blank area of the Library list. iPhoto imports the photos, storing them in their own event. iPhoto also creates an album and adds the photos to it.

Tip

As your collection of albums and other items grows, you may find that you no longer have a “blank area” at the bottom of the iPhoto window. To create one, close some of the items in the Library list—for example, close the Albums list by clicking its triangle.

Albums and flagging. iPhoto’s flagging feature (page 138) teams up nicely with albums. Want to create an album of shots that are scattered throughout your library? Flag the shots, then select the Flagged item in your Library list. Next, choose Edit > Select All, then choose File > New Album from Selection.

You’ve created an album containing the best photos of a friend’s wedding. The photos are from various events; indeed, some were emailed to you from other attendees.

You’d prefer that the photos were in an event of their own. Easy. Select the album, choose Edit > Select All, then choose Events > Create Event. iPhoto creates a new event, and moves the photos in the album into the event. Note, however, that the photos are removed from the events where they originated.

You can have iPhoto display the number of photos in each album next to each album’s name. In the Preferences dialog box, click General, then check the Show Item Counts box.

You have a photo that appears in multiple albums, but you want to edit its appearance in just one album, leaving the original version unchanged in other albums. Time for the Duplicate command: select the photo and choose Duplicate from the Photos menu (![]() -D). Now edit the duplicate.

-D). Now edit the duplicate.

Duplicating an album. There may be times when you’ll want several versions of an album. For example, you might have one version with photos sequenced for a slide show and another version with photos organized for a book. Or you might simply want to experiment with several different photo arrangements until you find the one you like best.

iPhoto makes this kind of experimentation easy. Simply duplicate an album by selecting the album and choosing Duplicate from the Photos menu. iPhoto makes a duplicate of the album, which you can rename and experiment with.

You can make as many duplicates of an album as you like. You can even duplicate a smart album—perhaps as a prelude to experimenting with different search criteria. Don’t worry about devouring disk space. Albums don’t include your actual photos; they simply contain “pointers” to the photos in your library.

Another good reason to create albums surfaces elsewhere in iLife: iMovie, iDVD, GarageBand, and iWeb all display iPhoto albums in their photo media browsers.

Have a batch of photos you want to use in another iLife program? Rather than searching through your library using those programs’ media browsers, first stash the photos in an album. Then, choose that album in the other iLife program.

iPhoto album support is also built into other programs, including Mac OS X’s screen saver and Apple’s iWork programs. And you can choose to sync only certain albums to a photo-capable iPod (page 210) or Apple TV (page 214).

iPhoto can assemble albums for you based on criteria that you specify. The smart album feature works much like the smart playlist feature in iTunes: spell out what you want, and your Mac does the work for you.

A few possibilities: Create an album containing every shot you took in the last week. Or of every photo you took in November 2002. Or of every November 2002 photo that has Sophie in its title. Or of every photo from 2007 that has Paris as a keyword, croissant in its title, and a rating of at least four stars.

If you’ve taken the time to assign titles, comments, and keywords to your photos, here’s where your investment pays off. You can still use smart albums if you haven’t assigned titles and other information to photos; you just won’t be able to search on as broad a range of things.

You can also create smart albums that have criteria based on information that your camera stores with each photo (see page 229). Create one smart album that corrals all the shots you took with your Sony camera, and another that collects all your Canon shots. Or create a smart album of all your photos shot at a high ISO speed (page 232), or at a fast shutter speed, or with a telephoto lens.

Smart albums are a great way to quickly gather up related photos for printing, backing up, browsing, emailing—you name it.

Choose New Smart Album from the File menu (Option-

-N).

-N).You can also create a new smart album by pressing the Option key and clicking on the

button in the lower-left corner of the iPhoto window.

button in the lower-left corner of the iPhoto window.Specify what to look for.

Click OK or press Return.

In the Albums area, iPhoto indicates smart albums with a special icon:

.

.

To modify a smart album, select it in the Albums area and choose File > Edit Smart Album or Photos > Smart Album Info (![]() -I).

-I).

Get more smart album ideas. www.macilife.com/iphoto

Many photos can benefit from some tweaking. Maybe you’d like to crop out that huge telephone pole that distracts from your subject. Maybe the exposure is too light, too dark, or lacks contrast. Or maybe the camera’s flash gave your subject’s eyes the dreaded red-eye flaw.

iPhoto’s edit view can fix these problems and others. And it does so in a clever way that doesn’t replace your original image.

Better still, a significant improvement in iPhoto ’08 gives you more editing flexibility. In earlier iPhoto versions, making changes to an already-edited image wasn’t the best idea—because of JPEG compression (there’s that word again), you’d lose a bit of image quality with each editing session.

iPhoto ’08 works differently. When you edit a photo, iPhoto keeps a list of the changes you made. If you reopen an edited image and make more changes, iPhoto applies your entire list of changes to the original version of the photo. It’s called nondestructive editing, and the result is fewer passes through the JPEG-compression meat grinder—and better photo quality. (For more about iPhoto non-destructive editing, including an important caveat, see page 229.)

As you get accustomed to iPhoto editing, you might want to experiment with full-screen editing (page 168), the separate editing window (page 170), and the ability to tweak some editing preferences (pages 24 and 175).

To work on a photo, open it in iPhoto’s edit view.

Select the photo you want to edit.

Click the Edit button.

The photo opens in edit view, and new tools and buttons appear (opposite page).

Now what? Here are some the ways iPhoto can help an ailing photo.

Table . Photo First-Aid

Symptom | Cure (and Page) |

|---|---|

Red-eye from flash | Red-Eye tool (154) |

Poor contrast and “punch” | Enhance button (156); for more control, the Adjust panel (162) |

Crooked and/or badly framed | Straighten and/or Crop tools (155) |

Scratches or blemishes | Retouch tool (157) |

Color balance is incorrect | Adjust panel (164) |

Photo is “grainy” from low light | Adjust panel (167) |

Change your mind? To exit edit view without saving any changes, press the Esc key.

Global or local? When you edit a photo, you change the photo everywhere you’ve used it—in slide shows, books, and calendars, for example. There’s another way to fine-tune an image. When printing a photo or using it in a book, greeting card, or calendar, you can modify the photo’s appearance in just that place—without changing its appearance elsewhere.

I’ll remind you of these local editing opportunities as we go.

Some photos can benefit from...less. Maybe you weren’t able to get close enough to your subject, and you’d like to get rid of some visual clutter. Or maybe a scenic vista is marred by a dumpster that you didn’t notice when you took the shot. Or maybe you want to order a print, and you want your photo’s proportions to match the size you want.

iPhoto’s Crop tool is the answer for jobs like these. By cropping a photo, you can often improve its composition and better highlight its subject matter.

Similarly, some photos need a bit of straightening. It’s easy to tilt the camera when you’re shooting, making the whole world look just a little crooked.

To put your world on the level, use the Straighten tool. A drag of the mouse is all it takes.

Then there’s red-eye. Biologically, it’s caused by the bright light of an electronic flash reflecting off a subject’s retinas and the blood vessels around them. Aesthetically, it makes people look like demons.

iPhoto can help here, too. The RedEye tool gives you a couple of ways to get the red out.

Open the photo in edit view.

Drag the size slider to zoom in on the subject’s eyes.

Click the Red-Eye tool.

Click the red eyes.

If you aren’t happy with the results—maybe there’s some red left over—choose Edit > Undo, then customize the Red-Eye tool and try again.

To turn off the Red-Eye tool, click it again or choose a different tool.

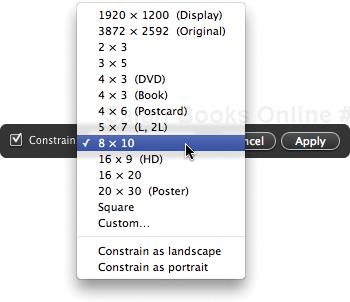

Constraining the crop. You can make the crop area any size you like. But sometimes, you may want to control the proportions of the crop area—to ensure that your photo’s proportions match a certain print size, for example.

Click the Constrain box, then choose an option.

For example, if you plan to order an eightby ten-inch print of the photo, choose 8 × 10.

To switch between a horizontal and vertical crop area, choose Constrain as Landscape or Constrain as Portrait. To override the constrain setting, press Shift while resizing the crop area.

Resetting the crop. To start over, press Option—the Cancel button changes to Reset. Click Reset, and iPhoto restores the original crop rectangle.

Cropping and resolution. When you crop a photo, you throw away pixels, lowering the photo’s resolution. If you print a heavily cropped photo, you may notice ugly digital artifacts. Always shoot at the highest resolution your camera provides; this gives you more flexibility to crop later (see page 232).

The local option. If you’re printing a photo on your own printer, or using the photo in a slide show or print project, you might prefer to use iPhoto’s zoom tools to crop—that way, you won’t change the photo everywhere you’ve used it. See pages 181 (for slide shows), 198 (for printing), and 211 (for print projects).

Old photos can appear faded, their color washed out by Father Time. They might also have scratches and creases brought on by decades of shoebox imprisonment.

New photos can often benefit from some enhancement, too. That shot you took in a dark room with the flash turned off—its color could use some punching up. That family photo you want to use as a holiday card—the clan might look better with fewer wrinkles and blemishes.

iPhoto’s enhance and retouch tools are ideal for tasks like these. With the enhance tool, you can improve a photo’s colors and exposure, and rescue a photo you might otherwise delete. With the retouch tool, you can remove minor scratches and blemishes, not to mention that chocolate smudge on your kid’s face.

iPhoto’s editing features make it easy to fix many common image problems, but iPhoto isn’t a full-fledged digital darkroom. You can’t, for example, remove power lines that snake across an otherwise scenic vista, nor can you darken only a portion of an image. For tasks like these, you’ll want to use Adobe Photoshop or Photoshop Elements—both of which pair up beautifully with iPhoto (see page 176).

To apply one-click enhance, open a photo in edit view, and then click the Enhance button at the bottom of the iPhoto window.

If at first you don’t succeed, click, click again. Each time you click Enhance, iPhoto processes the image again. But too much enhancement can make an image appear grainy and artificial. If that happens, choose Undo Enhance Photo from the Edit menu as many times as needed to backtrack.

If the Enhance tool isn’t doing the job—maybe its results are too harsh—undo your enhancements and turn to the tools in the Adjust panel (see page 160).

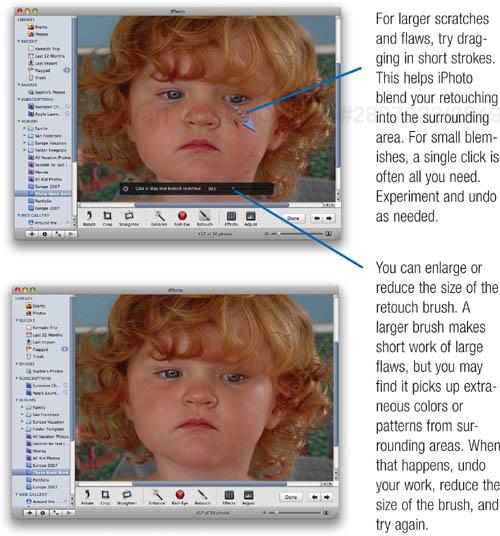

Zoom for precision. To retouch with more precision, use the size slider to zoom in on the area of the image that you’re working on. You can also zoom by pressing the 0 (zero), 1, or 2 keys.

Undo and revert. You can undo each mouse click or drag by choosing Edit > Undo Retouch from the Edit menu.

To undo all of your retouching, choose Photos > Revert to Previous. Note that you’ll also lose any other edits, such as cropping, that you performed since switching into edit view. Because of this, you might want to retouch first—that way, you won’t lose work if you decide to revert. Or take a different approach: Do your cropping and other adjustments, then click Done to exit edit view. Reopen the photo, and retouch.

Brush keyboard shortcuts. To make the retouch brush smaller, press the leftbracket ([) key. To make the brush larger, press the right-bracket key.

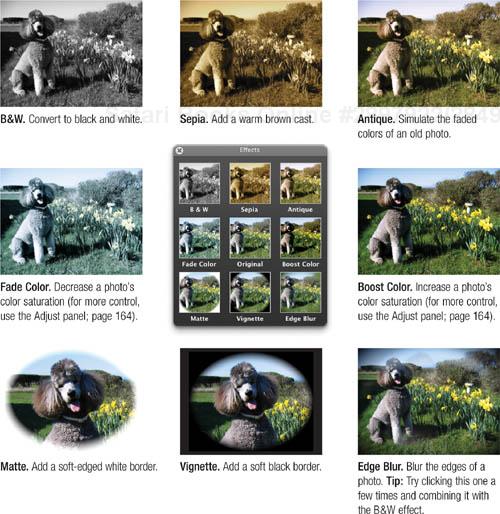

With the Effects panel, you can alter a photo to give it a unique look. Evoke the colors of an old, faded tintype. Turn a color photo into a black-and-white one. Blur the edges of a scene to create a gauzy, romantic look. Juice up the colors in a photo or tone them down.

As the tips at right describe, you can apply more than one effect to a photo, and you can apply an effect more than once.

Keep in mind that applying an effect to a photo changes that photo everywhere it appears—in albums, books, slide shows, and so on. If you want to retain the previous version of a photo, be sure to duplicate it before applying an effect: select the photo and choose Duplicate from the Photos menu or use the ![]() -D keyboard shortcut.

-D keyboard shortcut.

And there’s a local editing angle, too: You can apply black-and-white or sepia effects locally in a slide show. In print projects, you can apply these effects as well as an antique effect.

Combining effects. Some effects pair up particularly well. For a dream-like look, try combining Edge Blur with the B&W effect. For an old-fashioned look, pair the Sepia or Antique effects with the Vignette effect. To create an oval border around a photo, combine the Matte and Vignette effects.

Don’t be afraid to try offbeat combinations, either. It might seem contradictory to follow the Boost Color effect with the Fade Color effect, but you can get some interesting results when you do.

If you effect yourself into a corner, just click the Original button in the center of the Effects panel to return to safety.

When once isn’t enough. You can apply most effects up to nine times: simply click the desired effect’s button over and over again. (The two exceptions are the B&W and Sepia effects; clicking their buttons repeatedly will only wear out your mouse.)

iPhoto lets you know how many times you’ve applied an effect. To backtrack one time, click the left-pointing arrow.

Refining an effect. You can refine the appearance of an effect by using the controls in the Adjust panel (discussed on the following pages). In particular, you can improve the contrast and tonal range of a black-and-white conversion by adjusting the Saturation, Tint, and Temperature sliders. For details, see page 165.

Some photos need more help than others. That portrait captures the essence of your subject—but it’s just a bit dark. That shot of a beautiful white gardenia would be prettier if the flower didn’t have a jaundiced yellow color cast. And that shot of the dog playing in the park would be cuter if you could actually see the dog.

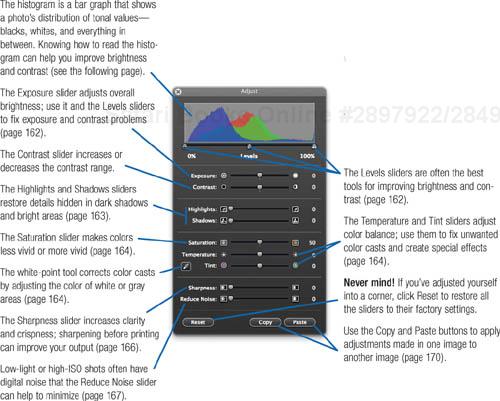

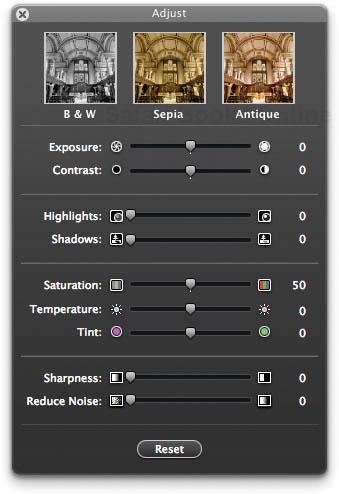

To fix problems like these, use the Adjust panel—its controls let you fine-tune exposure, tweak color balance, sharpen details and more.

The basics of the Adjust panel are a cinch: after opening a photo for editing, summon the Adjust panel by clicking the Adjust button in the edit view toolbar. Then, drag the appropriate sliders left or right until you get the desired results.

That last part—getting the desired results—isn’t always a cinch. Adjusting exposure, color balance, and sharpness can be tricky, and knowing a few digital imaging concepts can help you reach your goals. You’ll find a detailed look at these concepts in the following pages. Here’s the big picture.

Use the Exposure and Levels sliders to brighten or darken photos and improve contrast (page 162).

Use the Saturation, Temperature, and Tint sliders to remove unwanted color casts, increase or decrease color vividness, and more (page 164).

Use the Shadow and Highlight sliders to bring detail out of dark shadows and overly bright areas (page 163).

The local angle. You’ll find an Adjust panel elsewhere in iPhoto: there’s one in the custom print view (page 198) and in the calendar, greeting card, and book views (page 211). These Adjust panels aren’t identical to the one in edit view, but they’re very similar—and they’re great places to adjust a photo without changing it everywhere you may have used it.

iPhoto’s Enhance button often does a good job of punching up a photo, but it’s a “my way or the highway” feature: you either like its results or you undo.

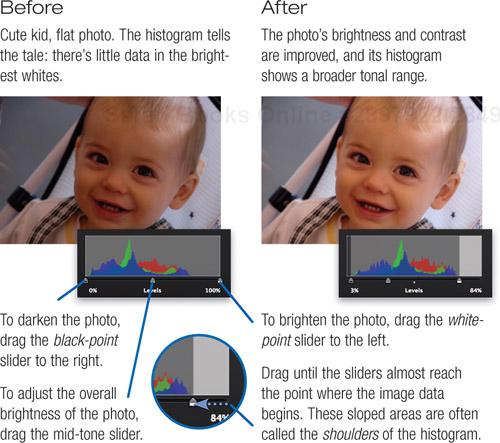

The Adjust panel is a more accommodating place to fix brightness and contrast problems. For improving a photo’s exposure and contrast, use the Levels sliders and the Exposure slider. By adjusting them—while keeping a close eye on the photo’s histogram—you can often make dramatic improvements in a photo’s appearance.

Which tools should you use? It depends on the photo. Some photos respond better to the Exposure slider, while others benefit from levels adjustments. Still other photos benefit from both approaches: do some initial tweaks with the Exposure slider, then fine-tune the levels.

When you drag the these sliders, you tell iPhoto to stretch the photo’s existing tonal values to cover a broader tonal range. Oversimplified, when you change the black point, you tell iPhoto, “See this grayish black? I want you to treat it as a darker black and adjust everything else accordingly.”

The Levels sliders can often work wonders, but they can’t work miracles. If a photo has an extremely narrow contrast range, you may see visible banding—jarring color shifts instead of smooth gradations—after adjusting levels. You’re telling iPhoto to stretch a molehill into a mountain, and there may not be enough data to allow for smooth gradations in shading and color.

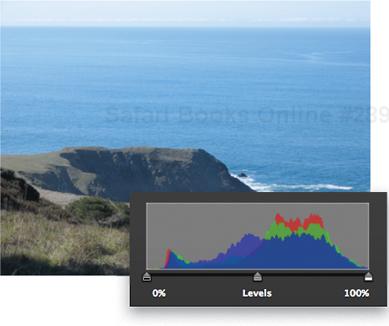

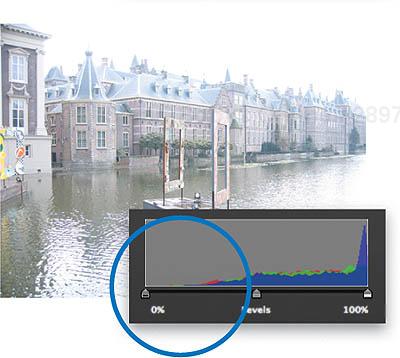

A histogram is a bar graph that shows how much black, white, and mid-tone data a photograph has. Pure black is on the left, pure white is on the right, and the mid-tones are in between. iPhoto displays a color histogram that breaks this information down into an image’s three primary-color channels: red, green, and blue.

Beneath the histogram is a set of sliders that let you change what iPhoto considers to be pure black, pure white, or mid-tone values.

This properly exposed shot has a good distribution of dark, bright, and mid-tone areas. Notice that the histogram shows a lot of bright blue data: the ocean and sky.

This overexposed shot has very little data in the blacks; everything is bunched up toward the right side—the white side—of the histogram.

Nice close-up, but the whites could be a bit whiter; notice the absence of data at the right end of the histogram.

The Adjust panel’s Exposure slider makes a photo brighter or darker.

I enhanced this underexposed photo by dragging the Exposure slider to the right. Notice that its histogram is broader than the original (see opposite page).

Note

The Exposure slider works best with raw-format images. For JPEG-format images, the Levels sliders tend to provide more precision. For more details, see page 175.

Cameras don’t perceive high-contrast scenes as well as our eyes do. As a result, high-contrast photos are often missing something. Shadows are dark and devoid of detail, or bright areas are washed out to nearly pure white. Take a photo of a friend under a beach umbrella, and you’ll probably see a silhouette, not a smile.

The Shadow and Highlight sliders in the Adjust panel can help. To bring out details hidden in dark areas of a photo, use the Shadow slider. It might just bring a smile to your silhouetted friend’s face. And to recover details in the brilliantly lit beach sand, drag the Highlights slider.

But a little goes a long way. It’s easy to end up with an artificial-looking photo that has strange halos where bright and dark areas meet. To recover shadow details, try brightening the photo with the mid-tone or white-point Levels slider, then drag the Shadow slider a bit. You might even try brightening the photo until highlights appear too bright, then darken them a bit by using the Highlights slider.

And that’s a good guideline for all your Adjust panel endeavors: the best results often come from combinations of several adjustments, not just one.

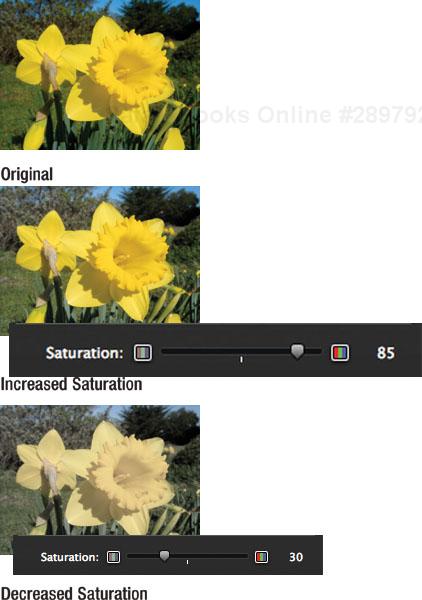

The Adjust panel lets you perform several types of color-related adjustments. With the Saturation slider, you can adjust the vividness of a photo’s colors. Turn down the saturation to create a muted look or to compensate for a camera’s overly enthusiastic built-in color settings. Or turn up the saturation to make a photo’s colors more intense.

With the Temperature and Tint sliders, you can change a photo’s color balance. Fix a color cast introduced by artificial light or caused by fading film. Or create a special effect to make a photo feel warmer or colder.

How can you tell if the colors you see on your screen will accurately translate to an inkjet or photographic print? Advanced Photoshop users rely on display-calibration hardware and other tools to calibrate their systems so that displayed colors match printed colors as closely as possible.

You can apply this strategy to iPhoto. Or you can take a simpler approach. First, calibrate your screen using the Displays system preference. Second, if you’ll be creating your own inkjet prints, make test prints as you work on a photo, duplicating the photo as necessary to get different versions.

Finally, as with many aspects of the Adjust panel, there’s a local angle to color adjustments. When you’re printing a photo or using it in a print project, you can use the Adjust panel in those views to change colors without changing the photo everywhere you’ve used it.

To make a photo’s colors more vivid, drag the Saturation slider to the right. To make colors more muted, drag the slider to the left.

Pale and pastel. To give a pastel-like quality to a photo’s colors, decrease the saturation.

Going gray. If you drag the Saturation slider all the way to the left, you create a grayscale version of the photo. Generally, the B&W button does a better job, but experiment and see which version you like best.

Watch your gamut. If you significantly increase a photo’s saturation, you probably won’t be able to print a version that matches what you see on screen. Printers have a much narrower color range, or gamut, than does the Mac’s screen.

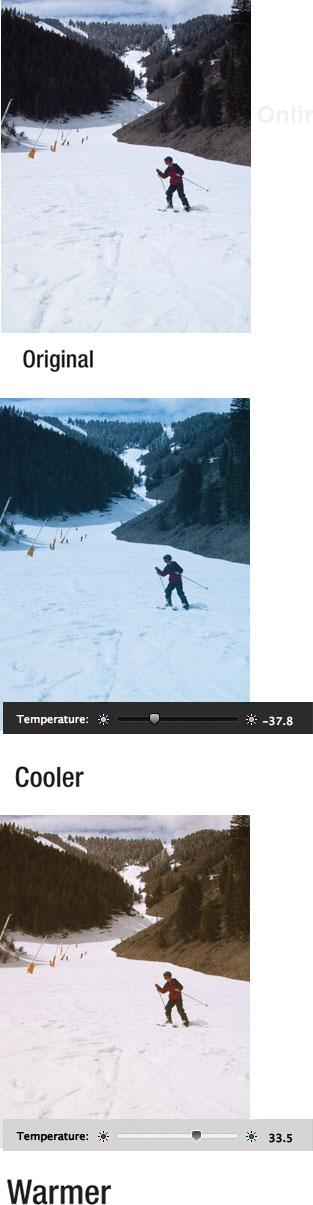

To adjust a photo’s color balance, use the Temperature slider, the Tint slider, or both.

Temperature. The Temperature slider adjusts a photo’s color temperature. To make a photo appear cooler (more bluish tones), drag the slider to the left. To make a photo appear warmer (more yellow/orange tones), drag the slider to the right.

Tint. The Tint slider adjusts red/green color balance. If you drag the slider to the left, iPhoto adds red, making a photo appear less green. If you drag the slider to the right, you add green and lessen the amount of red. The Tint slider can help remove the greenish color cast that you may find in photos taken under fluorescent lighting.

Temperature Tips. Photos taken under incandescent light with your camera’s flash turned off tend to have a yellowish cast to them. I like this warm look, but if you don’t, try dragging the Temperature slider to the left to cool things off. If the corrected image looks dark, bump up the Exposure or mid-tone Levels slider.

You can often simulate different lighting conditions by shifting a photo’s color temperature slightly. Warm up a photo to simulate late afternoon sun, or cool it down to simulate shade or twilight.

Old color photos often take on a reddish-yellow appearance as their color dyes fade. To fix this, drag the Temperature slider to the left a bit.

Gray Balancing. If you have an off-color photo containing an object that you know should be gray or white, click the eyedropper tool (![]() ), then click on part of the photo that should be gray or white. iPhoto adjusts the Temperature and Tint sliders as best it can to make the object a neutral gray.

), then click on part of the photo that should be gray or white. iPhoto adjusts the Temperature and Tint sliders as best it can to make the object a neutral gray.

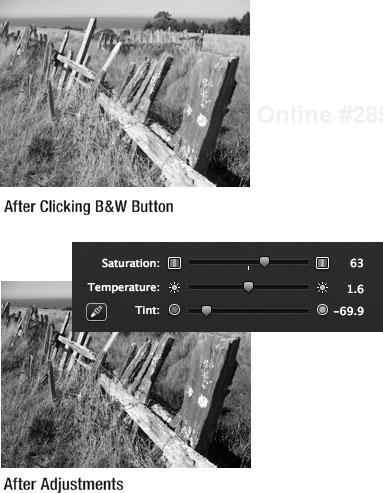

iPhoto’s B&W effect does a good job of converting a color photo to black and white, but you can often improve on its efforts: after clicking B&W, adjust the Saturation, Temperature, and Tint sliders.

When you drag the color sliders after converting a photo to black and white, iPhoto blends the photo’s red, green, and blue color channels in different ways. To make a black-and-white photo appear richer, bump up the saturation after clicking the B&W button. While you’re experimenting, drag the Temperature and Tint sliders to see how they alter the photo’s tonal values. (For you film fogies, this is the digital equivalent of exposing black-and-white film through color filters.)

All digital images—whether captured by a scanner or a camera—have an inherent softness. Some softness is introduced by inexpensive lenses. Still more is introduced by imaging sensors and their fixed grid of pixels.

Digital cameras compensate for this inherent softness by applying some sharpening immediately after you take a photo. You can often adjust the amount of sharpness they apply; I like to turn down the sharpness settings on my cameras, preferring to sharpen later, if necessary. (If you shoot in raw mode, your camera applies little or no sharpening to the image; see page 172.)

Inkjet printers and offset printing presses (including the kind used to print iPhoto books, greeting cards, and calendars) also introduce some softness. The bottom line: several factors are working against your image to obscure fine details.

And that’s where sharpening can help. By sharpening a photo just before printing it, you can often get a much better print.

Just because digital images have an inherent softness doesn’t mean that you should apply sharpening to every photo you take. First, consider the photo itself. A photo that lacks fine details—say, a close-up of a baby’s face—won’t gain much from sharpening, and may even be hurt by it. Conversely, a photo containing fine details—such as the one on the opposite page—may benefit greatly from sharpening.

Also consider how you’ll be using the photo. A photo destined for an iDVD slide show or iMovie project probably doesn’t need sharpening. A photo that you plan to print—either yourself or by ordering prints or a book—is a better candidate for sharpening, especially if the photo contains fine details.

Printing? Sharpen heavily. Don’t be afraid to heavily sharpen a photo that you’re going to print. Even if the photo looks a bit too sharp on screen, chances are it will print nicely.

iPhoto’s edit view introduces some softness of its own when it scales a photo to whatever zoom setting you’ve made. To get the most accurate on-screen view possible, view your photo at 100 or 200 percent when making sharpness adjustments: press the 1 key to view at 100 percent, and the 2 key to view at 200 percent.

Also consider the paper you’re using. Premium glossy photo paper shows fine details best, so photos destined for it can benefit from sharpening. On the other hand, matte- and luster-finish photo papers have a fine texture that obscures detail a bit.

The local angle. Just want to sharpen a photo for printing on your inkjet printer? Don’t forget the option of sharpening using the Adjust panel in the custom print view—see page 199.

Regardless of what you see on TV, no digital imaging program can turn a blurry photo into a sharp one. Instead, iPhoto detects boundaries of light and dark, and it makes light edges a bit lighter and dark edges a bit darker. When it’s done right—that is, not to excess—our eyes perceive this as increased sharpness.

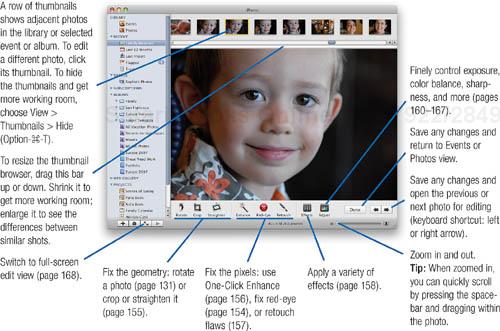

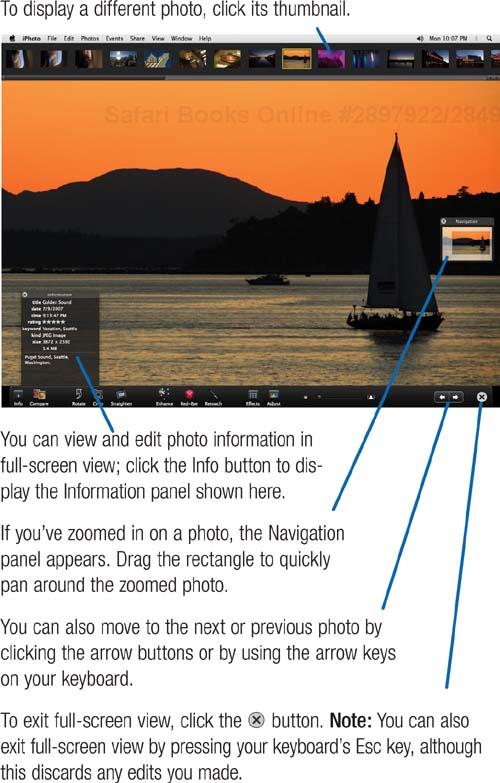

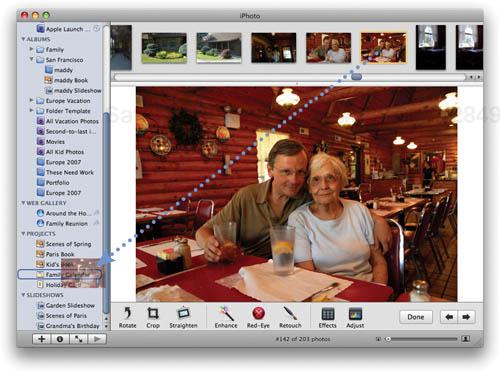

When you’re editing and enhancing a photo, it’s often helpful to see the big picture—that is, to display your photo at as large a size as possible. When you go big, it’s easier to perform color and exposure adjustments and to find flaws that need retouching.

iPhoto’s full-screen editing view gives you a picture window into your pictures. Click the Full Screen button, and your Library list and iPhoto’s buttons and controls step aside to make room for your photos. Move the mouse pointer to the top or bottom of the screen, and the menu bar or toolbar glide into view.

If you prefer to use full-screen view for all your editing tasks, use iPhoto’s Preferences command to always have photos open in full-screen view; see page 170.

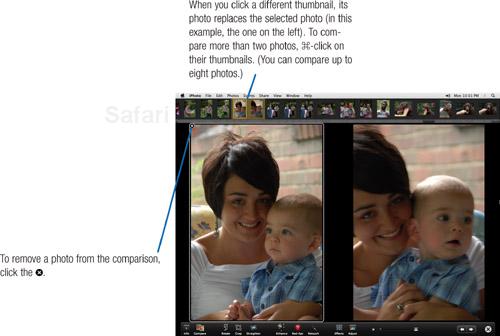

Full-screen view teams up nicely with another iPhoto feature: the ability to compare two or more photos in order to find the best shot in a series. You can display two or more photos side-by-side and even edit them.

It’s worth noting that you can also compare photos in iPhoto’s standard edit view and in the editing window (see page 232). But, because full-screen view maximizes your screen space, it’s the best place for your photo-comparison sessions.

To edit a photo in full-screen view, select the photo and then click the Full Screen button (![]() ).

).

If you’re already in the standard edit view, you can switch to full-screen view by clicking the same button.

It’s always smart to take more than one version of an important shot—to experiment with different exposure settings or to simply increase your chances of capturing that perfect smile.

After you’ve imported those multiple variations into iPhoto, compare the photos to find the best one. (And if you don’t want to see the rest, consider hiding them; see page 138.)

Comparing in edit view. If you’re already working in full-screen edit view (opposite page), click the Compare button ( ). iPhoto loads the next photo and displays both side-by-side.

). iPhoto loads the next photo and displays both side-by-side.

From browsing to comparing. You can also set up a comparison before entering edit view. Select the photos first, then click the Full Screen button (![]() ). For a review of ways to select photos, see page 147.

). For a review of ways to select photos, see page 147.

Normally, iPhoto displays the image you’re editing within the iPhoto window itself. But you can also open and edit a photo in a separate window that has its own editing toolbar.

You can have multiple edit windows open simultaneously, which makes it easy to compare images. For example, if you’ve duplicated a photo a few times and are trying out different sharpening or exposure-correction approaches, you can open each version in its own window and compare them—and work on them at once.

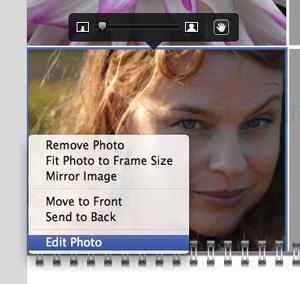

To open an image in a separate window, Control-click on it and choose Edit in Separate Window from the shortcut menu.

Prefer editing in full-screen view? Or in the separate editing window? Use the Preferences command to control where iPhoto opens your photos for editing.

Choose iPhoto > Preferences, click General, then choose an option from the Edit Photo pop-up menu. To always edit in full-screen view, choose Using Full Screen. For the separate edit window, choose In Separate Window.

Here are a few tips for taking advantage of the edit window.

Showing thumbnails. Normally, the edit window doesn’t display a photo browser containing thumbnails of adjacent images. If you’d like to see them, choose View > Thumbnails > Show.

Switching between windows. When you have multiple edit windows open simultaneously, use the Window menu to switch between them and the main iPhoto window. Or use the keyboard: press ![]() -~ (that’s the tilde, located above the Tab key) to cycle through open windows. That key sequence works in many Mac programs.

-~ (that’s the tilde, located above the Tab key) to cycle through open windows. That key sequence works in many Mac programs.

Zooming differently. Unlike iPhoto’s standard edit view, the edit window has a Size pop-up menu that lets you choose a specific zoom percentage for your photo. As I mentioned on the previous page, if you’re sharpening, you’ll get the most accurate preview of your work by viewing at 100 or 200 percent.

Resizing the window. Remember that you can quickly resize the edit window to fill your screen by clicking the green button in the upper-left corner of the window or choosing Window > Zoom.

Sometimes, you might have a series of photos that can benefit from the same adjustments—maybe they’re all similarly dark, for example, or all have the same color cast.

With the Copy and Paste buttons in the Adjust panel, you can apply one photo’s adjustments to other photos. After tweaking a photo to perfection, click the Copy button in the Adjust panel. Next, open a different photo in edit view, display the Adjust panel, and click Paste.

You can activate various editing tools by pressing a single key on your keyboard (see the table below).

Table . Keyboard Editing

For this tool | Press |

|---|---|

Crop | C |

Straighten | S |

Red-eye | R |

Retouch | T |

Adjust panel | A |

Effects panel | E |

White-point tool | W |

While you’re pawing your keyboard, remember that you can open a photo for editing by selecting the photo and pressing the Return key—you don’t have to click the Edit button. To save changes and return to thumbnail browsing, press Return. To save changes and edit an adjacent photo, press an arrow key. To discard changes and exit edit view, press Esc. And to switch to full-screen edit view, press Option-![]() -F.

-F.

Want to go straight from browsing photos to editing one? Press Option while double-clicking a photo’s thumbnail, and it opens in edit view. (And remember, if you always want iPhoto to work this way, use the Preferences command to set it up.)

Most of the time, you probably enter edit view while browsing your library or an album. But you can also enter edit view while working on a book, calendar, or greeting card: just Control-click on the photo and choose Edit Photo from the shortcut menu.

The thumbnail browser—that row of images at the top of the edit view—is a handy tool for quickly accessing another photo in the same event or album.

But it has another use, too: you can drag a thumbnail from the photo browser directly into an album, book, or slide show. If you’re on an editing binge and suddenly realize that a certain photo would go nicely in a specific album, slide show, or book, there’s no need to exit edit view. Just drag the photo from the photo browser to the album, slide show, or book.

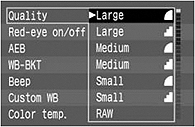

If you’re an advanced photographer, a control freak, or both, there’s an image format that may change the way you shoot. The image format is called raw, and it’s supported by many mid-range and virtually all high-end cameras.

Here’s why raw matters. When you shoot in JPEG format, your camera permanently alters the photo: tweaking color balance and saturation, adjusting sharpness, and compressing the image to use less space.

Today’s cameras do these jobs well, but you pay a price: you lose some control. You can still adjust the color balance, exposure, and sharpness of a JPEG image, but within a relatively narrow range. Exceed those limits, and you risk visible flaws.

When you shoot in raw mode, your camera saves the exact data recorded by its light sensors. Instead of being locked into the camera’s alterations, you get the original, unprocessed image data: the raw data. Transfer this raw image to the Mac, and you can use iPhoto or other imaging software to fine-tune the image to a degree that the JPEG format doesn’t permit.

Shooting raw has drawbacks, and many photographers prefer the convenience and efficiency of JPEG. But for pixel perfectionists who want maximum control—especially over shots taken in tricky lighting conditions, such as candlelight—raw is the best way to shoot.

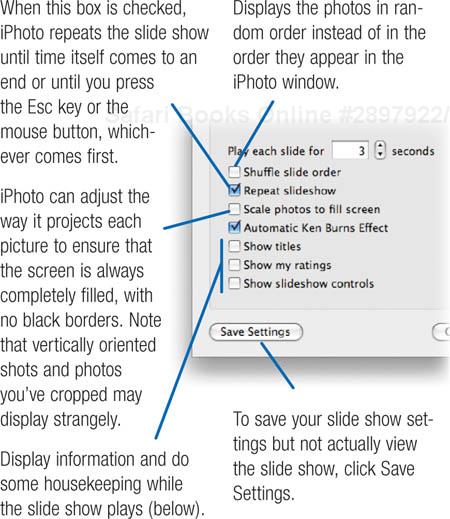

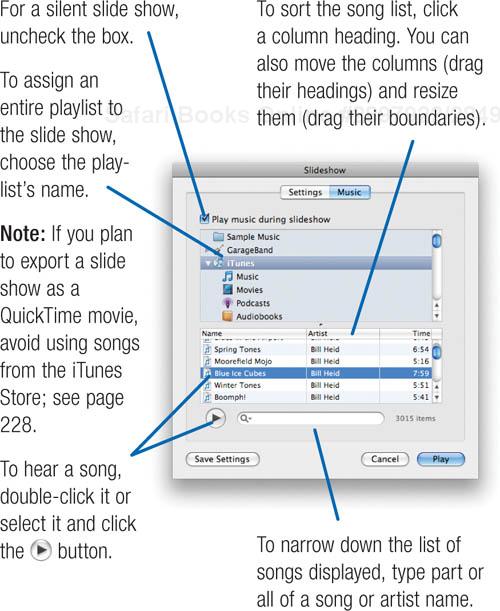

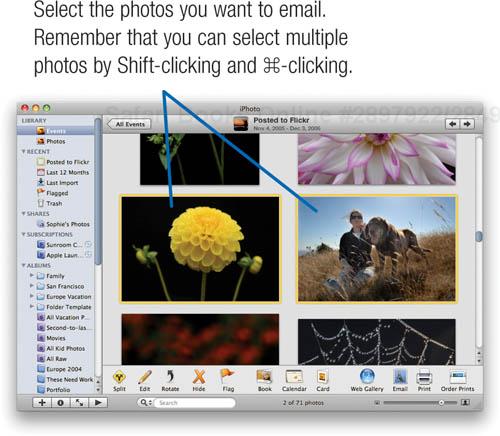

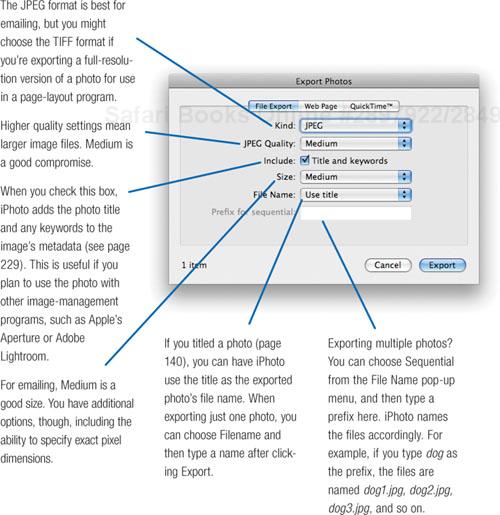

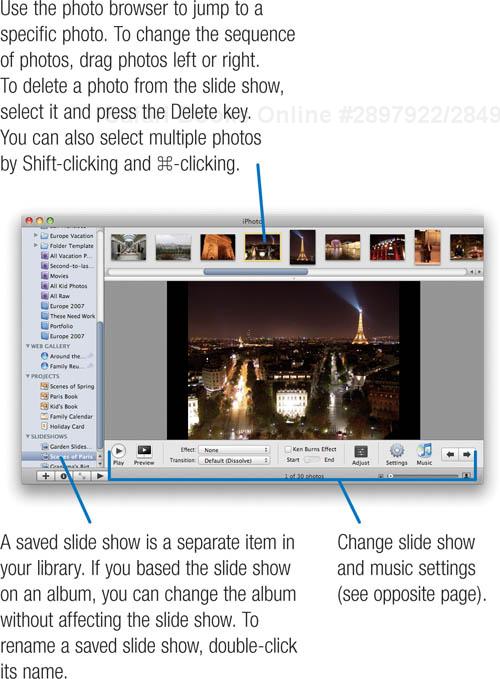

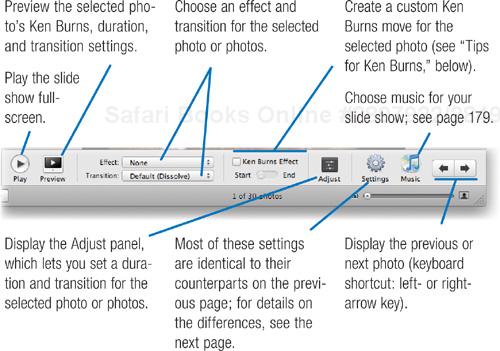

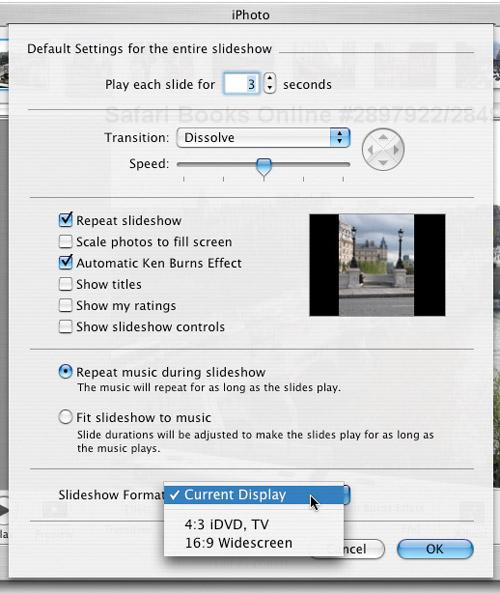

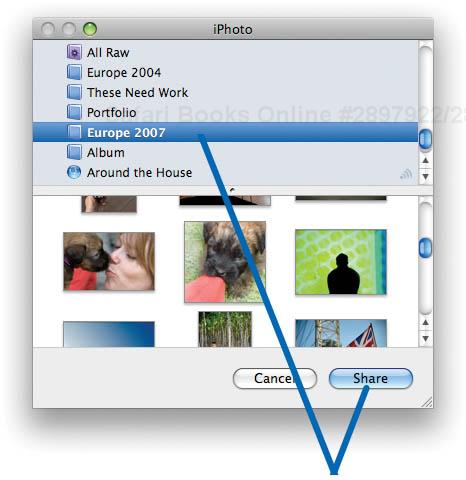

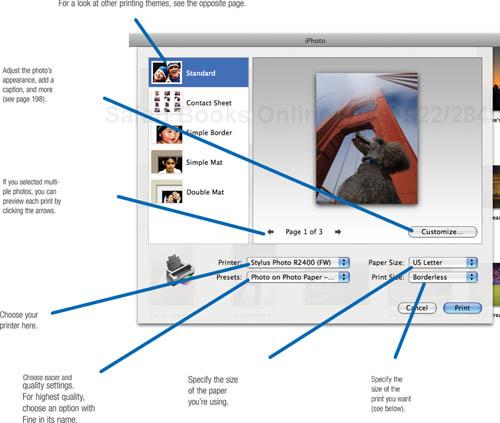

To shoot in raw mode, venture into your camera’s menus—specifically, to the menu that controls image format. In some cameras, you’ll find this option in the Mode menu. With others, such as the Canon EOS-10D shown here, this option is in the Quality menu.