What does the digital do to knowledge making?

Just as a child who has learned to grasp stretches out its hand for the moon as it would for a ball, so humanity, in all its efforts at innervation, sets its sights as much on currently utopian goals as on goals within reach. Because… technology aims at liberating human beings from drudgery, the individual suddenly sees his scope for play, his field of action, immeasurably expanded. He does not yet know his way around this space. But already he registers his demands on it (Benjamin [1936] 2008, p. 242).

Representation is integral to knowledge making. It is not enough to make knowledge, as the prognosticating Darwin did for many decades before the publication of The Origin of Species. For knowledge to become germane, to attain the status of knowledge proper, it needs to be represented to the world. It needs, in other words, to be put through the peculiarly social rituals of publishing.

This chapter argues that changes in the modes of representation of knowledge have the potential to change the social processes of knowledge making. To be specific, we want to argue that the transition from print to digital text has the potential in time to change profoundly the practices of knowledge making, and consequently knowledge itself.

But, you may respond, representation is a mere conduit for the expression of knowledge. Having to write The Origin of Species did not change what Darwin had discovered. The process of discovery and the process of representation are separated in time and space, the latter being impassively subordinate to the former. The publishing practices that turn knowledge into scholarly journals and monographs are mere means to epistemic ends.

We want to argue that the practices of representation are more pervasive, integral and influential in the knowledge-making process than that. For a start, before any discovery, we knowledge makers are immersed in a universe of textual meaning—bodies of prior evidence, conceptual schemas, alternative critical perspectives, documented disciplinary paradigms and already-formulated methodological prescriptions. The social knowledge with which we start any new knowledge endeavour is the body of already-represented knowledge. We are, in a sense, captive to its characteristic textualities. (In the following chapter, we call these ‘available designs’ of knowledge.) Next, discovery. This is not something that precedes in a simple sequence the textual processes publication. Discovery is itself a textual process—of recording, of ordering thoughts, of schematising, of representing knowledge textually to oneself as a preliminary to representing that knowledge to a wider knowledge community. There can be no facts or ideas without their representation, at least to oneself in the first instance. How often does the work of writing give clarity to one’s thoughts? (In the next chapter, we call this ‘designing knowledge’.) Then, knowledge is of little or no import if it is not taken through to a third representational step. In the world of scholarly knowledge this takes the form of rituals of validation (peer and publisher review) and then the business of public dissemination, traditionally in the forms of academic articles and monographs. (In the next chapter, we will call this ‘the (re)designed’, the representational traces left for the world of knowledge, becoming now ‘available designs’ for the social cycle of knowledge making to start again.)

How could changing the medium of knowledge representation have a transformative effect on these knowledge design processes? We want to argue that when we change the means of representation, it is bound to have significant effects, later if not sooner. In this chapter, we explore the already visible and potential further effects of the shift to the representation of knowledge through digital media.

The work of knowledge representation in the age of its digital reproducibility

A new translation of Walter Benjamin’s essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ has changed the rather inert phrase ‘mechanical reproduction’ in earlier translations to ‘technological reproducibility’ (Benjamin [1936] 2008). This shift poignantly speaks to possibility rather than technological inevitability, and affordance, which creates a space for meaning making instead of deterministic consequences. In his essay Benjamin argues that something in art changes once it becomes reproducible. This is the case not only for the tangibly new manifestations of representation that emerge, such as photography and cinema, but in the nature of art itself, even the nature of seeing. Painting has an aura of instance-specific authenticity such that copies present as forgeries, whereas the photographic image is designed for its reproducibility. Photography opens new ways of seeing accessible only to the lens, things not visible to the naked eye which can be enlarged, or things not noticed by the photographer but noticed by the viewer. Cinema substitutes for the theatre audience a group of specialist viewers—the executive producer, director, cinematographer, sound recordist, and so on—who may on the basis of their expert viewing intervene in the actor’s performance at any time. Photography is like painting, and cinema is like theatre, but both also represent profound changes in the social conditions of the production and reception of artistic meaning (Benjamin [1936] 2008).

So it is in the case of the textual representation of knowledge. Here, we’re in the midst of a broader revolution in means of production of meaning, at the heart of which are digital technologies for the fabrication, recording and communication of meaning. What does this revolution mean? What are its affordances? This is not to ask what consequences follow from the emergence of this new mode of mechanical reproduction. Rather it is to ask what are its possibilities? What does it allow that we might mean or do with our meanings? What new possibilities for representation does it suggest? What are the consequences for knowledge making and knowledge representation?

In answering these questions, our counterpoint will be the world of print. How might the textual representation of knowledge change in the transition from the world of print to the world of digital text? We will examine six areas of current or imminent change. Each of these areas brings potentially enormous change to the processes of knowledge creation and representation:

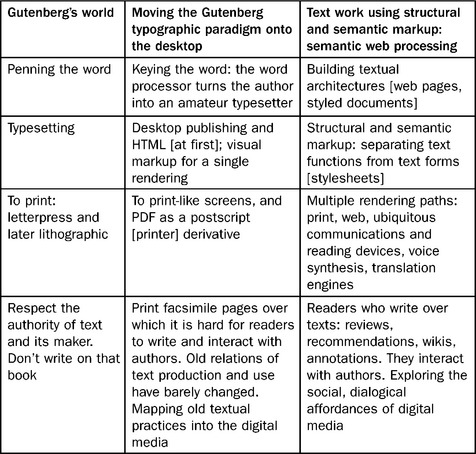

![]() A significant change is emerging in the mechanics of rendering, or the task of making mechanically reproduced textual meaning. In the world of print, text was ‘marked up’ for a single rendering. In the emerging world of the digital, text is increasingly marked up for structure and semantics (its ‘meaning functions’), and this allows for alternative renderings (various ‘meaning forms’, such as print, web page or audio) as well as more effective semantic search, data mining and machine translation.

A significant change is emerging in the mechanics of rendering, or the task of making mechanically reproduced textual meaning. In the world of print, text was ‘marked up’ for a single rendering. In the emerging world of the digital, text is increasingly marked up for structure and semantics (its ‘meaning functions’), and this allows for alternative renderings (various ‘meaning forms’, such as print, web page or audio) as well as more effective semantic search, data mining and machine translation.

![]() A new navigational order is constructed in which knowledge is accessed by moving between layers of relative concreteness or abstraction.

A new navigational order is constructed in which knowledge is accessed by moving between layers of relative concreteness or abstraction.

![]() This is intrinsically a multimodal environment, in which linguistic, visual and audio meanings are constructed of the same stuff by means of digital technologies.

This is intrinsically a multimodal environment, in which linguistic, visual and audio meanings are constructed of the same stuff by means of digital technologies.

![]() It is an environment of ubiquitous recording, allowing for unprecedented access to potentially reuseable data.

It is an environment of ubiquitous recording, allowing for unprecedented access to potentially reuseable data.

![]() This environment has the potential to change the sources and directions of knowledge flows, where the sources of expertise are much more widely distributed and the monopoly of the university or research institute as a privileged site of knowledge production is challenged by much more broadly distributed sites of knowledge production.

This environment has the potential to change the sources and directions of knowledge flows, where the sources of expertise are much more widely distributed and the monopoly of the university or research institute as a privileged site of knowledge production is challenged by much more broadly distributed sites of knowledge production.

![]() Whereas English and other large European languages have historically dominated scientific and scholarly knowledge production, this is likely to be influenced by the inherently polylingual potentials of the new, digital media.

Whereas English and other large European languages have historically dominated scientific and scholarly knowledge production, this is likely to be influenced by the inherently polylingual potentials of the new, digital media.

The old and the new in the representation of meaning in the era of its digital reproduction

In this chapter we are concerned to address the question of the nature and significance of the changes to practices of representation and communication for knowledge production in the digital era. Some changes, however, may be less important than frequently assumed. The ‘virtual’ and hypertext, for instance, are founded on practices and phenomena entirely familiar to the half-millennium-long tradition of print. They seem new, but from the point of view of their epistemic import, they are not so new. They simply extend textual processes which support knowledge moves which are as old as modernity.

The hyperbole of the virtual

The new, digital media create a verisimilitude at times so striking that, for better or for worse, the elision of reality and its represented and communicated forms at times seem to warrant the descriptive label ‘virtual reality’.

However, there is not much about the virtual in the digital communications era which print and the book did not create as a genuine innovation 500 years earlier. As a communication technology, print first brought modern people strangely close to distant and exotic places through the representation of those places in words and images on the printed page. So vivid at times was the representation that the early moderns could be excused for thinking they were virtually there. So too, in their time, the photograph, the telegraph, the newspaper, the telephone, the radio and the television were all credited for their remarkable verisimilitude— remarkable for the ‘real’ being so far away, yet also for being here and now—so easily, so quickly, and so seemingly close and true to life.

Each of these new virtual presences became a new kind of reality, a new ‘telepresence’ in our lives (Virilio 1997). We virtually lived through wars per medium of newspapers; and we virtually made ourself party to the lives of other people in other places and at other times through the medium of the novel or the travelogue. In the domain of formal knowledge representation, Darwin transported us to the world of the Galapagos Islands, astronomers into realms of space invisible to the naked eye, and social scientists into domains of social experience with which we may not have been immediately familiar.

In this respect, digitisation is just another small step in the long and slow journey into the cultural logic of modernity. We end up addressing the same tropes of proximity, empirical veracity and authenticity that have accompanied any practice of representation in the age of mechanical reproduction of meaning. The significance of the virtual in representation has been multiplied a thousand times since the beginning of modernity, with the rise of the printing press and later the telegraph, the telephone, sound recording, photography, cinema, radio and television. However, digitisation in and of itself adds nothing of qualitative significance to this dynamic. It just does more—maybe even a lot more—of the same.

The hype in hypertext

Hypertext represents a new, non-linear form of writing and reading, it is said, in which readers are engaged as never before as active creators of meaning (Chartier 2001).

However, even at first glance, hypermedia technologies are not so novel, tellingly using metaphorical devices drawn from the textual practices of the book such as ‘browsing’, ‘bookmarking’, ‘pages’ and ‘index’. Moreover, when we examine the book as an information architecture, its characteristic devices are nothing if not hypertextual. Gutenberg’s Bible had no title page, no contents page, no pagination, no index. In this sense, it was a truly linear text. However, within half a century of Gutenberg’s invention, the modern information architecture of the book had been developed, including regularly numbered pages, punctuation marks, section breaks, running heads, indexes and cross-referencing. Among all these, pagination was perhaps the most crucial functional tool (Eisenstein 1979).

The idea that books are linear and digital text is multilateral is based on the assumption that readers of books necessarily read in a linear way. In fact, the devices of contents, indexing and referencing were designed precisely for alternative lateral readings, hypertextual readings, if you like. This is particularly the case for knowledge texts rather than novels, for instance. And the idea that the book or a journal article is a text with a neat beginning and a neat end—unlike the internet, which is an endless, seamless web of cross-linkages—is to judge the book by its covers or the journal article by its tangible beginning and end. However, a book or a journal article sits in a precise place in the world of other books, either literally when shelved in a library, and located in multiple ways by sophisticated subject cataloguing systems, or more profoundly in the form of the apparatuses of attribution (referencing) and subject definition (contents and indexes).

As for hypertext links that point beyond a particular text, all they do is what citation has always done. The footnote developed as a means of linking a text back to its precise sources, and directing a reader forward to a more detailed elaboration (Grafton 1997). The only difference between the footnote and hypertext is that in the past you had to go to the library to follow through on a reference. This relationship to other writing and other books comes to be regulated in the modern world of private property by the laws, conventions and ethics of copyright, plagiarism, quotation, citation, attribution and fair use (Cope 2001b).

Certainly, some things are different about the internet in this regard. Clicking a hypertext link is faster and easier than leafing through cross-referenced pages or dashing to the library to find a reference. But this difference is a matter of degree, not a qualitative difference. For all the hype in hypertext, it only does what printed books and journal articles have always done, which is to point to connections across and outside a particular text.

These are some of the deeply hypertextual processes by which a body of knowledge has historically been formed, none of which change with the addition of hypertext as a technology of interconnection. From an intertextual point of view, books and journal articles are interlinked through referencing conventions (such as citation), bibliographical practices (such as library cataloguing), and the inherent and often implicitly intertextual nature of all text (there is always some influence, conscious or unconscious, something that refracted from other works notwithstanding the authorial conceit of originality). From an extratextual point of view, books and journal articles always have semantic and social reference points. Semantically, they direct our attention to an external world. This external reference is the basis of validity and truth propositions, such as a pointer to an authentic historical source, or a scientifically established semantic reality located in a controlled vocabulary, such as C = carbon. The subject classification systems historically developed by librarians attempt to add structure and consistency to extratextual semantic reference. From an extratextual point of view, texts also have an acknowledged or unacknowledged ontogenesis—the world of supporters, informers, helpers, co-authors, editors and publishers that comprises the social-constructivist domain of authorship and publishing. Not to mention those at times capricious readers—texts enter this social world not as authorial edict, but open to alternative reading paths, in which communicative effects constructed as much by readerly as they are by authorial agendas.

To move on now to things that, in some important respects, are genuinely new to the emerging digital media.

The mechanics of rendering

Many say that the invention of the printing press was unequivocally the pre-eminent of modernity’s world-defining events. Huge claims are made for the significance of print—as the basis of mass literacy and modern education, as the foundation of modern knowledge systems, and even for creating a modern consciousness aware of distant places and inner processes not visible to the naked eye of everyday experience (Febvre and Martin 1976).

Print created a new way of representing the world. Contents pages and indexes ordered textual and visual content analytically. A tradition of bibliography and citation arose in which a distinction was made between the author’s voice and ideas and the voice and ideas of other authors. Copyright and intellectual property were invented. And the widely used modern written languages we know today rose to dominance and stabilised, along with their standardised spellings and alphabetically ordered dictionaries, displacing a myriad of small spoken languages and local dialects (Phillipson 1992).

The cultural impact of these developments was enormous: modern education and mass literacy; the rationalism of scientific knowledge; the idea that there could be factual knowledge of the social and historical world (Grafton 1997). These things are in part a consequence of the rise of print culture, and give modern consciousness much of its characteristic shape.

What was the defining moment? Was it Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of moveable type in 1450 in Mainz, Germany? This is what the Eurocentric version of the story tells us. By another reckoning, the defining moment may have been the invention of clay moveable type in China by Li Sheng in about 1040CE, or of wooden moveable type by Wang Zhen in 1297, or of bronze moveable type by officials of the Song Dynasty in 1341 (Luo 1998). Or, if one goes back further, perhaps the decisive moments were the Chinese inventions of paper in 105CE, wood block printing in the late sixth century and book binding in about 1000CE. Whoever was first, it is hard to deny that the Gutenberg invention had a rapid, world-defining impact, while the Chinese invention of moveable type remained localised and even in China was little used. Within 50 years of the invention of the Gutenberg Press there were 1,500 print shops using the moveable type technology located in every sizeable town in Europe; and 23,000 titles had been produced totalling eight million volumes (Eisenstein 1979). The social, economic and cultural impact of such a transformation cannot be underestimated.

We will focus for a moment on one aspect of this transformation, the processes for the rendering of textually represented meanings. In this analysis our focus will be on the tools for representation, on the means of production of meaning. For the printing press marks the beginning of the age of mechanical reproduction of meaning. This is new to human history and, however subtly, it is a development that changes in some important respects the very process of representation.

Gutenberg had been a jeweller, and a key element of his invention was the application of his jeweller’s skills to the development of cast alloy moveable type. Here is the essence of the invention: a single character is carved into the end of a punch; the punch is then hammered into a flat piece of softer metal, a matrix, leaving an impression of the letter; a handheld mould is then clamped over the matrix, and a molten alloy poured into it. The result is a tiny block of metal, a ‘type’, on the end of which is the shape of the character that had been carved into the punch. Experienced type founders could make several hundred types per hour. The type was then set into formes—blocks in which characters were lined up in rows, each block making up a page of text—assembled character by character, word by word, line by line. To this assembly Gutenberg applied the technology of the wine press to the process of printing; the inked forme was clamped against a sheet of paper, the pressure making an impression on the page. That impression was a page of manufactured writing (Man 2002).

The genius of the invention was that the type could be reused. After printing, the formes could be taken apart and the type used again. But the type was also ephemeral. When the relatively soft metal wore out, it could easily be melted down and new types moulded. One set of character punches was all that was needed to make hitherto unimaginable numbers of written words an infinite number of alternative textual combinations: the tiny number of punches producing as many matrices as were needed to mould a huge number of types in turn producing seemingly endless impressions on paper saying any manner of things that could be different from work to work. Indeed, Gutenberg invented in one stroke one of the fundamental principles of modern manufacturing: modularisation. He had found a simple solution to the conundrum of mass and complexity. Scribing a hand-written book, or making a hand-carved woodblock (which incidentally, remained the practice in China, well after Gutenberg and despite the earlier invention of moveable type by the Chinese), is an immensely complex, not to mention time-consuming, task. By reducing the key manufacturing process (making the types) to the modular unit of the character, Gutenberg introduced a process simplicity through which complex texts could easily and economically be manufactured.

Gutenberg, however, had also created a new means of production of meaning. Its significance can be evaluated on several measures: the technology of the sign, epistemology of the sign and social construction of the sign. The technology of the sign was centred around the new science and craft of ‘typography’. The practices of typography came to rest on a language of textual design centred on the modular unit of the character, not only describing its size (in points), visual design (fonts) and expressive character (bold, italic, book). It also described in detail the spatial arrangements of characters and words and pages (leading, kerning, justification, blank space) and the visual information architecture of the text (chapter and paragraph breaks, orders of heading, running heads, footnotes). Typography established a sophisticated and increasingly complex and systematised science of punctuation—a series of visual markers of textual structure with no direct equivalent in speech. The discourse of typography described visual conventions for textual meaning in which meaning function was not only expressed through semantic and syntactic meaning forms but also through a new series of visual meaning forms designed to realise additional or complementary meaning functions.

The new regime of typography also added a layer of abstraction to the abstraction already inherent in language. Representation of the world with spoken words is more abstract than representation through images expressing resemblance, and this by virtue of the arbitrary conventions of language. Writing, in turn, is more abstract than oral language. Vygotsky says that writing is ‘more abstract, more intellectualised, further removed from immediate needs’ than oral language and requires a ‘deliberate semantics’, explicit about context and self-conscious of the conditions of its creation as meaning (Vygotsky 1962). With printing, further distance was added between expression and rendering, already separated by writing itself. The Gutenberg invention added to the inherent abstractness of writing. This took the form of a technical discourse of text creation which was, in a practical sense, so abstracted from everyday reality that it became the domain of specialist professionals: the words on the page, behind which is the impression of the forme on the paper, behind which is the profession of typography, behind which is the technology of type, a matrix and a punch. Only when one reaches the punch does one discover the atomic element on which the whole edifice is founded. The rest follows, based on the principles of modularisation and the manufacturing logic of recomposition and replication.

The social construction of the sign also occurs in new ways, and this is partly a consequence of these levels of scientific and manufacturing abstraction. With this comes the practical need to remove to the domain of specialists the processes, as well as the underlying understanding of the processes, for the manufacture of the sign. Speech and handwriting are, by comparison, relatively unmediated. To be well formed and to take on the aura of authoritativeness, printed text is constructed through a highly mediated chain of specialists, moving from author, to editor, to typesetter, to printer, and from there to bookstores, libraries and readers. Each mediation involves considerable backwards and forwards negotiation (such as drafting, refereeing, editing, proofing and markup) between author, editor, typesetter, printer, publisher, bookseller and library. The author only appears to be the font of meaning; in fact texts with the aura of authority are more socially constructed than the apparently less authored texts of speech and handwriting. What happens is more than just a process of increasing social construction based on negotiation between professionals. A shift also occurs in the locus of control of those meanings that are ascribed social significance and power. Those who communicate authoritatively are those who happen to be linked into the ownership and control of the means of production of meaning—those who control the plant that manufactures meaning and the social relations of production and distribution of meaning.

What are the consequences for knowledge making? The world of scholarly publishing is profoundly shaped by the modes of textuality established by print. Knowledge texts establish ‘facts’ and the validity of truth propositions by external reference: tables of data, footnotes and citations referring to sources, documentation of procedures of observation and the like. These texts place a premium on accuracy through processes of proofing, fact-checking, errata and revised editions. They construct hierarchical, taxonomical information architectures through chapter ordering, multilevel sectioning and highlighting of emphasis words. They include managed redundancy which makes this taxonomic logic explicit: tables of contents, introduction, chapter and other heading weights, summaries and conclusions. This creates a visual compartmentalisation and didactic sequencing of knowledge (Ong 1958). These texts distinguish authorial from other voices by insisting on the attribution of the provenance of others’ ideas (citation) and the visual differentiation and sourcing of other’s texts (quotation). To authorship, biographical authority is ascribed by institutional affiliation and publishing track record. All text also goes through a variety of social knowledge validation processes, involving publishers, peer reviewers and copy editors, and post-publication reviews and citation by other authors. Not that these are necessarily open or objective—indeed, this system reinforces the structural advantages of those at the centres of epistemic power in a hierarchical social/knowledge system, whose shape is as often determined by positional circumstance as intellectual ‘excellence’. From this a body of knowledge is constructed, powerfully integrated by citation and bibliography. Knowledge, once disclosed by publication, is discoverable through tables of contents, indexes, pagination and bookstore or library shelving systems. Print reproduction allows the replication of this body of language by considerable duplication of key texts in multiple libraries and bookstores.

None of this changes, in the first instance, with the transition to digital text. Rather, we begin a slow transition, which in some respects may, as yet, have barely begun. The first 50 years of print from 1450 to 1500 is called the ‘incunabula’—it was not until 1500 that the characteristic forms of modern print evolved. Jean-Claude Guedon says we are still in the era of a digital incunabula (Guedon 2001). Widespread digitisation of part of the text production process has been with us for many decades. The Linotron 1010 phototypesetter, a computer which projected character images onto bromide paper for subsequent lithographic printing, was first put into use at the US Government Printing Office in 1967. By 1980 most books were phototypeset.

After phototypesetting, domestic and broad commercial applications of digitisation of text were led by the introduction of word processing and desktop publishing systems. However, it was not until the late 1990s that we witnessed the beginnings of a significant shift in the mechanics of digital representation. Until then, text structure was defined by the selfsame discourse of ‘markup’ that typesetters had used for 500 years. Historically, the role of the typesetter had been to devise appropriate visual renderings of meaning form on the basis of what they were able to impute from the meaning functions underlying the author’s text. Markup was a system of manuscript annotation, or literally ‘marking up’ as a guide to the setting of the type into a visually identifiable textual architecture. This is where the highly specialised discourse of typography developed.

The only transition of note in the initial decades of digitisation was the spread of this discourse into the everyday, non-professional domains of writing (the word processor) and page layout (desktop publishing software). Never before had non-professionals needed to use terminology such as ‘font’, ‘point size’ or even ‘leading’—the spaces between the lines which had formerly been blocked out with lead in the formes of letterpress printing. This terminology had been an exclusive part of the arcane, professional repertoire of typesetters. Now authors had to learn to be their own typesetters, and to do this they had to learn some of the language of typography. As significant as this shift was, the discourse of typography remained essentially unchanged, as well as the underlying relations of meaning function to meaning form.

The Gutenberg discourse of typography even survived the first iteration of Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), the engine of the World Wide Web (Berners-Lee 1990). This was a vastly cut-down version of Standardised General Markup Language (SGML), which had originated in the IBM laboratories in the early 1970s as a framework for the documentation of technical text, such as computer manuals (Goldfarb 1990). SGML represents a radical shift in markup practices, from typographic markup (visual markup by font variation and spatial layout) to the semantic and structural markup which is now integral to digital media spaces. Figure 4.1 shows a fragment of SGML markup, the definition of ‘bungler’ for the 1985 edition of the Oxford Dictionary.

Particularly in its earliest versions in the first half of the 1990s, HTML was driven by a number of presentationally oriented ‘tags’, and in this regard was really not much more than a traditional typographic markup language, albeit one designed specifically for web browsers. Its genius was that it was based on just a few tags (about 100) drawn from SGML, and it was easy to use, accessible and free. Soon it was to become the universal language of the World Wide Web. However, Tim Berners-Lee bowdlerised SGML to create HTML, contrary to its principles mixing typographic with structural and semantic markup. The five versions of HTML since then have tried to get back closer to consistent principle. Tags mark up the text for its structural (e.g. < sen >) and semantic (e.g. < auth >) features, thus storing information in a way that allows for alternative renderings (‘stylesheet transformations’) and for more accurate search and discovery.

The next step in this (in retrospect) rather slow and haphazard process was the invention of Extensible Markup Language or XML in 1998. XML is a meta-space for creating structural and/or semantic markup languages. This is perhaps the most significant shift away from the world of Gutenberg in the history of the digitisation text. This, too, is a vastly simplified version of SGML, albeit a simplification more rigorously true to the original SGML insight into the benefits of separating information architecture from rendering. Within just a few years, XML became pervasive, if mostly invisible—not only in the production of text but also increasingly in electronic commerce, mobile phones and the internet. It may be decades before the depth of its impact is fully realised.

Unlike HTML, which is a markup language, XML is a framework for the construction of markup languages. It is a meta markup language. The common ‘M’ in the two acronyms is deceptive, because marking up markup is an activity of a very different order from marking up. XML is a simplified syntax for the construction of any markup language. In this sense XML is also a significant departure from SGML. Consequently, XML is a space where a plethora of markup languages is appearing, including markup languages that work for the activities of authorship and publishing, and a space for the realisation of ontologies of all kinds, including upper-level spaces for framing ontologies such as Resource Description Framework (RDF) and Ontology Web Language (OWL).

XML brackets the logistics of presentation away from the abstract descriptive language of structure and semantics. Take the heading of this section of this chapter, for instance. In traditional markup, we might use the typographer’s analytical tool to mark this as a heading, and that (for instance) might be to apply the visual definition or command such as < 14pointTimesBold >. We could enact this command by a variety of means, and one of these is the screen-based tool of word processing or desktop publishing. The command is invisible to the reader; but somebody (the author or the typesetter) had to translate the meaning function ‘heading’ into a visual meaning form which adequately represents that function to a community capable of reading that visual rendering for its conventionally evolved meaning. If we were to mark up by structure and semantics, however, we might use the concept < heading >. Then, when required, and in a rigorously separated transformational space, this tag is translated through a ‘stylesheet’ into its final rendered form—and this can vary according to the context in which this information is to be rendered: as HTML by means of a web browser, as conventional print (where it may happen to come out as 14 point Times Bold, but could equally come out as 16 point Garamond Italic, depending on the stylesheet), as a mobile phone or electronic reading device, as synthesised voice, or as text or audio in translation to another language.

The semantic part of XML is this: a tag defines the semantic content of what it marks up. For instance, ‘cope’ is an old English word for a priest’s cloak; it is a state of mind; and it is the surname of one of the authors of this text. Semantic ambiguity is reduced by marking up ‘Cope’ as < surname >. Combined with a tag that identifies this surname as that of an < author > of this text, a particular rendering effect is created depending on the transformation effected by the stylesheet that has been applied. As a consequence, in the manufacturing process this author’s surname is rendered in the place where you would expect it to appear and in a way you could expect it to look—as a byline to the title.

And the structural part of XML is this: a framework of tags provides an account of how a particular domain of meaning hangs together, in other words how its core conceptual elements, its tags, fit together as a relatively precise and interconnected set of structural relations. A domain of meaning consists of a system of inter-related concepts. For instance, < Person>’s name may consist of < GivenNames > and < Surname >. These three concepts define each other quite precisely. In fact, these relations can be represented taxonomically— < GivenNames > and < Surname > are ‘children’ of the ‘parent’ concept < Person >. Put simply, the effect of markup practices based in the first instance on semantics and structure rather than presentation is that meaning form is rigorously separated from meaning function. Digital technologies (‘stylesheet transformations’) automate the manufacture of form based on their peculiar framework for translating generalised function into the particularities of conventional understandings and readings of form. When ‘Cope’ is marked up as < surname > and this is also a component of < author > (the meaning function), then the stylesheet transformation will interpret this to mean that the word should be located in a particular point size at a particular place on the title page of a book (the meaning form). Meaning and information architecture are defined functionally. Then form follows function.

From this highly synoptic account of shifts in digital text creation and rendering technologies we would like to foreground one central idea, the emergence of a new kind of means of production of meaning: text-made text. Text-made text represents a new technique and new mechanics of the sign. Text is manufactured via an automated process in which text produces text. Text in the form of semantic and structural tags drives text rendering by means of stylesheet transformation. This is a technology for the automated manufacture of text from a self-reflective and abstracted running commentary on meaning function. It is a new mode of manufacture which, we contend, may well change the very dynamics of writing, and much more profoundly so than the accretion of typesetting language into everyday textual practices which accompanied the first phase of digitisation in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Accompanying this new mechanics is a new epistemology of the sign. It is to be expected that the emergence of new representational means—new relations of meaning form to meaning function—will also entail new ways of understanding meaning and new ways of thinking. Writing acquires yet another layer of ‘conscious semantics’, to use the Vygotskian phrase, and one which Vygotsky could not possibly have imagined when he was working in the first half of the twentieth century. More than putting pen to paper, or fingers to keyboard, this new mechanics requires the self-conscious application of systematically articulated information architectures. In effect, these information architectures are functional grammars (referring to text structures) and ontologies (referring to the represented world).

However, even though we will soon be five decades into the development of digital text, digitisation still includes deeply embedded typographical practices—in word processing, desktop publishing, and the print-like Portable Document Format (PDF). These are old textual processes clothed in the garb of new technologies—and remain as barriers to many of the things that structural and semantic markup is designed to address: discoverability beyond character or word collocations, more accurate machine translation, flexible rendering in alternative formats and on alternative devices, non-linear workflow and collaborative authoring, to name a few of the serious deficiencies of typographic markup. Academic publishing, however, has yet barely moved outside the Gutenberg orbit.

Figure 4.2 shows the kinds of changes in textwork that are under way. The consequences for knowledge making of the shift to the third of these textual paradigms could be enormous, though barely realised yet.

Scholarly writers, more than any, would benefit from accurate semantic and structural markup of their texts, depending as they do for their knowledge work on finer and less ambiguous semantic distinctions than vernacular discourse. For instance, some domains are already well defined by XML schemas, such as Chemical Markup Language (ChemML). This is something they can most accurately do themselves, rather than publishers or automated indexing software. However their writing environments are still almost universally typographic. There is an urgent need for new text editing environments in whose operational paradigm might be called ‘semantic web processing’. (Common Ground’s CGAuthor environment is one such example.) When such a paradigm shift is made in the authoring processes of scholars, there will be a quantum leap in the accuracy and quality of search or discovery, data mining, rendering to alternative text and audio devices, accessibility to readers with disabilities, and machine translation.

A new navigational order

The digital media require users to get around their representational world in new ways. To be a new media user requires a new kind of thinking. In our textual journeys through these media we encounter multiple ersatz identifications in the form of icons, links, menus, file names and thumbnails. We work over the algorithmic manifestations of databases, mashups, structured text, tags, taxonomies and folksonomies in which no one ever sees the same data represented the same way. The person browsing the web or channel surfing or choosing camera angles on digital television is a fabricator and machine-assisted analyst of meanings. The new media, in other words, do just not present us with a pile of discoverable information. They require more work than that. Users can only navigate their way through the thickets of these media by understanding its architectural principles and by working across layers of meaning and levels of specificity or generality. The reader becomes a theoretician, a critical analyst, a cartographer of knowledge. And along the way, the reader can write as they read and talk back to authors, the dialogic effect of which is the formation of the reader who writes to read and the writer who reads to write. This is a new cognitive order, the textual rudiments of which arise in an earlier modernity, to be sure, as we argued earlier in the case of hypertext. However, what we have in the digital media is more than a more efficient system citation and cross reference—which is all that hypertext provides. More than this, we have processes of navigation and architectures of information design in the emerging digital regime that require a peculiarly abstracting sensibility. They also demand a new kind of critical literacy in which fact is moderated by reciprocal ecologies of knowledge validation and full of metadialogues around interest (the ‘edit history’ pages in wikis for instance). The resultant meanings and knowledge are more manifestly modal, contingent and conditional than ever before.

Let us contrast the knowledge processes of the traditional academic article or monograph with potential knowledge ecologies of the digital navigational order. With the increasing availability of articles in print facsimile PDF or other fixed digital delivery formats, nothing really changes other than a relatively trivial dimension of faster accessibility. Knowledge is still presented as linear, typographical text designed for conventional reading. We are presented with little or nothing more than the traditional typograhical or hypertextual navigation devices of abstracts, sectioning, citation and the like.

However, in the digital era it would be possible to present readers with a less textually mediated relation to knowledge. Data could be presented directly (quantitative, textual, visual) in addition to or even instead of the conventional exegesis of the scholarly article or monograph. Algorithmic ‘mashup’ layers could be added to this data. The assumption would be that readers of knowledge texts could construct for themselves more varied meanings than those issued by the author, based on their knowledge needs and interests. Also, the unidirectional knowledge flow transmitted from scholarly author to epistemically compliant reader could be transformed into a more dialogical relationship in which readers engage with authors, to the extent even of becoming the acknowledged co-constructors of knowledge.

Whereas print-facsimile publication has a one way irreversibility to it (barring errata or retractions in subsequent articles), scholarly authors would have the opportunity to revise and improve on already-published texts based on a more recursive knowledge dialogue. A scholarly rhetoric of empirical finality and theoretical definitiveness would be replaced by a more dynamic, rapidly evolving, responsive ecology of knowledge-as-dialogue. The mechanics of how this might be achieved are clearly manifest in today’s wikis, blogs and social media. It remains for today’s knowledge system designers to create such environments for scholarly publishing (Cope and Kalantzis 2009b; Whitworth and Friedman 2009a, 2009b).

Multimodality

The representational modality of written language rose to dominance in the era of print. However, a broad shift is now occurring away from linguistic and towards increasingly visual modes of meaning, reversing the language-centric tendencies of western meaning that emerged over the past half millennium (Kress 2001, 2009; Kress and van Leeuwen 1996). A key contributing factor to this development has been the potential opened by digital technologies. Of course, technology itself does not determine the change; it merely opens human possibilities. The more significant shift is in human semiotic practices.

Let us track back again to our counterpoint in the history of print, the moment of Gutenberg’s press. In the Christian religion of medieval Europe, faith was acquired through the visual imagery of icons, the audio references of chant, the gestural presence of priests in sacred garb, and the spatial relationships of priest and supplicant within the architectonic frame of the church. The linguistic was backgrounded, an audio presence more than a linguistic one insofar as the language of liturgy was unintelligible to congregations (being in Latin rather than the vernacular). And the written forms of the sacred texts were inaccessible in any language to an illiterate population (Wacquet 2001). Gutenberg’s first book was the Bible, and within a century the Reformation was in full swing. The Reformation sought to replace the Latin Bible with vernacular translations. These became an agent of, and a reason for, mass literacy. The effect of the printed Bible was to create congregations whose engagement with their faith was primarily written-linguistic—the sacred Word, for a people of the Book. The underlying assumptions about the nature of religious engagement were so radically transformed that Protestantism might as well have been a new religion.

So began a half-millennium-long (modern, Western) obsession with the power and authoritativeness of written language over other modes of represented meaning. One of the roots of this obsession was a practical consequence of the new means of production of meaning in which the elementary modular unit was the character. In a very pragmatic sense it was about as hard to make images as it had been to hand-make whole blocks before the invention of moveable type. Furthermore, with the rise of moveable type letterpress it was difficult, although not impossible, to put images on the same page as text—to set an image in the same forme as a block of text so that the impression of both text and image was as clear and even as it would have been had they been set into different formes. Until offset lithographic printing, if there were any ‘plates’ they were mostly printed in separate sections for the sake of convenience. If image was not removed entirely, text was separated from image (Cope 2001c).

So began a radical shift from image culture to the word culture of Western modernity (Kress 2000). This was taken so far as to entail eventually the violent destruction of images, the iconoclasm of Protestantism, which set out to remove the graven images of Catholicism in order to mark the transition to a religion based on personal encounter with the Word of God. This Word was now translated into vernacular languages, mass-produced as print and distributed to an increasingly literate populace. Gutenberg’s modularisation of meaning to the written character was one of the things that made the Western world a word-driven place, or at the very least made our fetish for writing and word-centredness practicable.

By contrast with the Gutenberg technology, it is remarkably easy to put the images and words together when digitally constructing meaning, and this is in part because text and images are built on the same elementary modular unit. The elementary unit of computer-rendered text is an abstraction in computer code made up of perhaps eight (in the case of the Roman character set) or sixteen bits (in the case of larger character sets, such as those of some Asian languages). This is then rendered visually through the mechanised arrangement of dots, or pixels (picture elements), the number of pixels varying according to resolution—a smallish number of dots rendering the particular design of the letter ‘A’ in 12 point Helvetica to a screen, and many more dots when rendering the same letter to a printer. Images are rendered in precisely the same way, as a series of dots in a particular combination differentiated range of halftones and colours. Whether they are text or images, the raw materials of digital design and rendering are bits and pixels.

In fact, this drift began earlier in the twentieth century and before digitisation. Photoengraving and offset lithographic printing made it much easier to put images and text on the same plane. Print came to be produced through a series of photographically based darkroom and film composition practices which created a common platform for image and type. Evidence of this increasing co-location of text and image is to be found by comparing a newspaper or school textbook of the third quarter of the twentieth century with its equivalent 50 or 100 years ago (Kress 2009).

Digitisation merely opens the way for further developments in this long revolution, by making the process of assembling and rendering juxtaposed or overlaid text and images simpler, cheaper and more accessible to non-tradespeople. And so, we take a journey in which visual culture is revived, albeit in new forms, and written-textual culture itself is more closely integrated with visual culture. Digitisation accelerates this process.

One of the practical consequences of this development is that, among the text creation trades, typesetting is on the verge of disappearing. It has been replaced by desktop publishing in which textual and visual design occur on the same screen, for rendering on the same page. Even typing tools, such as Microsoft Word, have sophisticated methods for creating (drawing) images, and also importing images from other sources, such as scanned images or photographic images whose initial source is digital. Digital technologies make it easy to relate and integrate text and images on the same page. Complex information architectures and multimodal grammars emerge around practices of labelling, captioning and the superimposition of text and image.

In retrospect, it is ironic that in the first phase of digitisation, a simplified version of the discourse of typography is de-professionalised, and that this discourse was a quintessential part of the writing-centric semiotics of the Gutenberg era. Reading is actually a matter of seeing, and in this phase of digitisation the attention of the text creator is directed to the visual aspect of textual design.

Since the last decade of the twentieth century another layer has been added to this multimodal representational scene by the digital recording of sound. With this, music, speaking and video or cinema can all be made in the same space. The result is that we are today living in a world that is becoming less reliant on words, a world in which words rarely stand simply and starkly alone in the linguistic mode. Sometimes the communication has become purely visual—it is possible to navigate an airport by using the international pictographs. In fact, standardised icons are becoming so ubiquitous that they represent an at least partial shift from phonology to graphology—in this sense we’re all becoming more Chinese.

There remains, however, a paradox, and that is the increasing use of written language tagging schemas for the identification, storage and rendering of digital media—visual and audio as well as textual. Prima facie, this seems to represent a setback in the long march of the visual. More profoundly, it may indicate the arrival of a truly integrated multimodality, with the deep inveiglement of the linguistic in other modes of meaning. Here, the linguistic is not just being itself, but also speaks of and for the visual.

The simple but hugely important fact is that, with digitisation, words, images and sound are, for the first time, made of the same stuff. As a consequence, more text finds its way into images with, for instance, the easy overlay of text and visuals, or the easy bringing together in video of image and gesture and sound and written-linguistic overlays. Television has much more writing ‘over it’ than was the case in the initial days of the medium—take the sports or business channels for instance.

Meanwhile, the world of academic knowledge remains anachronistically writing-centric (Jakubowicz 2009). It would add empirical and conceptual power, surely, to include animated diagrams, dynamically visualised datasets, and video and audio data or exegesis in published scholarly works. It would help peer reviewers see one layer beyond the author’s textual gloss which, in the conventional academic text, removes the reviewer one further representational step from the knowledge the text purports to represent.

The ubiquity of recording and documentation

In the era of mass communications recording was expensive. It was also the preserve of specialised industry sectors peopled by tradespeople with arcane, insider technical knowledge—typesetters, printers, radio and television producers, cinematographers and the like. Cultural and knowledge production houses were owned by private entrepreneurs and sometimes the state. The social power of the captains of the media industry or the apparatchiks of state communications were at least in part derived from their ownership and control of the means of production of meaning—the proprietors of newspapers, publishing houses, radio stations, music studios, television channels and movie studios. Cultural recording and reproduction were expensive, specialised and centralised.

There were some significant spaces where modern people could and did incidentally record their represented meanings in the way pre-moderns did not—in letters, telegrams, photographs and tape recordings, for instance. However, these amateur spaces almost always produced single copies, inaccessible in the public domain. These were not spaces that had any of the peculiar powers of reproduction in the era of ‘mass’ society.

By contrast, the new, digital media spaces are not just sites of communication; they are places of ubiquitous recording. They are not just spaces of live communication; they are sites of asynchronous multimodal communication of recorded meanings or incidental recording of asynchronous communication—emails, text messages, voicemails, Facebook posts and Twitter tweets. The recording is so cheap as to be virtually free. And widespread public communication is as accessible and of the same technical quality for amateurs as it is for professionals.

Despite these momentous shifts in the lifeworld of private and public communications, most knowledge production practices remain ephemeral—conference presentations, lectures, conversations, data regarded as not immediately germane, interactions surrounding data and the like. Unrecorded, these disappear into the ether.

Now that so much can be so effortlessly recorded, how might we store these things for purposes ancillary to knowledge production? What status might we accord this stuff that is so integral to the knowledge process, but which previously remained unrecorded? How might we sift through the ‘noise’ to find what is significant? What might be released into the public domain? And what should be retained behind firewalls for times when knowledge requires validation before being made public? These are key questions which our scholarly publication system needs to address, but thus far has barely done so. They will surely need to be addressed soon, given the ubiquity of recording in the new, social media.

A shift in the balance of representational agency

Here are some of the differences between the old media and the new. Whereas broadcast TV had us all watching a handful television channels, digital TV has us choosing one channel from among thousands, or interactive TV has us selecting our own angles on a sports broadcast, or YouTube has us making our own videos and posting them to the web. Whereas novels and TV soaps had us engaging vicariously with characters in the narratives they presented to us, video games make us central characters in the story to the extent that we can even influence its outcomes. Whereas print encyclopedias provided us definitive knowledge constructed by experts, Wikipedia is constructed, reviewed and editable by readers and includes parallel argumentation by readereditors about the ‘objectivity’ of each entry. Whereas broadcast radio gave listeners a programmed playlist, iPod users create their own playlists. Whereas a printed book was resistant to annotation (the limited size of its margins and the reader’s respect for other readers), new reading devices and formats encourage annotation in which the reading text is also (re)writing the text. Whereas the diary was a space for time-sequenced private reflection, the blog is a place for personal voice which invites public dialogue on personal feelings. Whereas a handwritten or typed page of text could only practically be the work of a single creator, ‘changes tracking’, version control and web document creation spaces such as Google Docs or Etherpad make multi-author writing easy and collaborative authorship roles clear (Kalantzis 2006a).

Each of these new media is reminiscent of the old. In fact, we have eased ourselves into the digital world by using old media metaphors— creating documents or files and putting them away in folders on our desktops. We want to feel as though the new media are like the old. In some respects they are, but in some harder-to-see respects they are quite different. Figure Error! Reference source not found. shows some apparent textual parallels.

The auras of familiarity are deceptive, however. If one thing is new about the digitised media, it is a shift in the balance of representational agency. People are meaning-makers as much as they are meaning-receptors. The sites of meaning production and meaning reception have been merged. They are writers in the same space that they are readers. Readers can talk back to authors and authors may or may not take heed in their writing. We are designers of our meaning-making environments as much as we are consumers—our iPod playlists, our collections of apps, our interface configurations. Blurring the old boundaries of writer-reader, artist-audience and producer-consumer, we are all ‘users’ now. And this, in the context of a series of epochal shifts which are much larger than digitisation: in post-Fordist workplaces where workers make team contributions and take responsibility measured in performance appraisals; in neo-liberal democracies where citizens are supposed to take increasingly self-regulatory control over their lives; and in the inner logic of the commodity in which ‘prosumers’ co-design specific use scenarios through alternative product applications and reconfigurable interfaces (Cope and Kalantzis 2009a; Kalantzis and Cope 2008).

This what we mean by the ‘changing balance of agency’ (Kalantzis 2006b; Kalantzis and Cope 2006). An earlier modern communications regime used metaphors of transmission—for television and radio, literally, but also in a figurative sense for scholarly knowledge, textbooks, curricula, public information, workplace memos and all manner of information and culture. This was an era when bosses bossed, political leaders heroically led (to the extent even of creating fascisms, communisms and welfare states for the ostensible good of the people), and personal and family life (and ‘deviance’) could be judged against the canons of normality. Now, self-responsibility is the order of the day. Diversity rules in everyday life, and with it the injunction to feel free to be true to your own identity.

Things have also changed in the social relations of meaning making. Audiences have become users. Readers, listeners and viewers are invited to talk back to the extent that they have become media co-designers themselves. The division of labour between culture and knowledge creators and consumers has been blurred. Consumers are also creators, and creators are consumers. Knowledge and authority are more contingent, provisional and conditional—based in relationships of ‘could’ rather than ‘should’. This shift in the balance of agency represents a transition from a society of command and compliance to a society of reflexive co-construction. It might be that the workers create bigger profits for the bosses, that neoliberalism ‘naturally’ exacerbates disparities in social power, and that diversity is a way of putting a nice gloss on inequality. The social outcomes, indeed, may at times be disappointingly unchanged or the relativities even deteriorating. What has changed is the way these outcomes are achieved. Control by others has become self-control; compliance has become self-imposed. New media are one part of this broader equation. The move may be primarily a social one, but the technology has helped us head in this general direction.

What are the implications for our ecologies of knowledge production? Contrast traditional academic knowledge production with Wikipedia. Anyone can write a page or edit a page, without distinction of social position or rank. The arbiters of quality are readers and other writers, and all can engage in dialogue about the veracity or otherwise of the content in the edit and edit history areas, a public metacommentary on the page. The roles of writers and readers are blurred, and textual validation is an open, explicit, public and inclusive process. This represents a profound shift in the social relations of knowledge production.

This is a time when the sources and directions of knowledge flows are changing. The sites and modes of knowledge production are undergoing a process of transformation. The university has historically been a specialised and privileged place for knowledge production, an institutionally bounded space, the site of peculiarly ‘disciplined’ knowledge practices. Today, however, universities face significant challenges to their traditional position as knowledge makers and arbiters of veracity. In particular, contemporary knowledge systems are becoming more distributed. More knowledge is being produced by corporations than was the case in the past. More knowledge is being produced in the traditional broadcast media. More knowledge is being produced in the networked interstices of the social web. In these places, the logics and logistics of knowledge production are disruptive of the traditional values of the university—the for-profit, protected knowledge of the corporation; the multimodal knowledge of the broadcast media; and the ‘wisdom of the crowd’, which destabilises old regimes of epistemic privilege through the new, web-based media.

How can the university connect with the shifting sites and modes of knowledge production? How can it stay relevant? Are its traditional knowledge-making systems in need of renovation? What makes academic knowledge valid and reliable, and how can its epistemic virtues be strengthened to meet the challenges of our times? How can the university meet the challenges of the new media in order to renovate the disclosure and dissemination systems of scholarly publishing? How can the university connect with the emerging and dynamic sources of new knowledge formation outside its traditional boundaries?

The answers to these large questions are to be found in part in the development of new knowledge ecologies, which exploit the affordances of the new, digital media. This will involve collaborations which blur the traditional institutional boundaries of knowledge production, partnering with governments, enterprises and communities to co-construct distributed knowledge systems. Taking lessons from the emergence of social media, we need to address the slowness and in-network closures of our systems for the declaration of knowledge outcomes—peer review, and journal and book publication systems. In the era of the social web, we anachronistically retain knowledge systems based on the legacies of print. We must design knowledge systems which are speedier, more reflexive, more open and more systemically balanced than our current systems (Cope and Kalantzis 2009b).

A new dynamics of difference

A key aspect of Gutenberg’s invention of letterpress printing was to create the manufacturing conditions for the mass reproduction of texts. This is another respect in which his invention anticipated, and even helped to usher in, one of the fundamentals of the modern world. Here, the idea of modularisation and the idea of mass production were integrally linked. The component parts of text were mass manufactured types assembled into formes. The atomic element of modularisation may have been reduced and rationalised; the process of assembly was nevertheless labour intensive. One printed book was far more expensive to produce than one scribed book. The economics of the printed book was a matter of scale, in which the high cost of set up is divided by the number of impressions. The longer the print run, the lower the per unit cost, the cheaper the final product and the better the margin that could be added to the sale price. Gutenberg printed only about 200 copies of his Bible, and for his trouble he went broke. He had worked out the technological fundamentals but not its commercial fundamentals. As it turned out, in the first centuries after the invention of the moveable type letterpress, books were printed in runs of about 1,000. We can assume that this was approximately the point where there was sufficient return on the cost of set up, despite their lower sale price than scribed books. Here begins a peculiarly modern manufacturing logic—the logic of increasing economies of scale or a logic which valorises mass.

Moreover, when culture and language are being manufactured, scale in discourse communities is crucial, or the assumption that there are enough people who can read and will purchase a particular text to justify its mass reproduction. At first, economies of scale were achieved in Europe by publishing in the lingua franca of the early modern cultural and religious intelligentsia, Latin. This meant that the market for a book was the whole of Europe, rather than the speakers of a local vernacular. By the seventeenth century, however, more and more material was being published in local vernaculars (Wacquet 2001). With the expansion of vernacular literacy, local markets grew to the point where they were viable. Given the multilingual realities of Europe, however, not all markets were of a sufficiently large scale. There were many small languages that could not support a print literature; there were also significant dialect differences within languages that the manufacturing logic of print ignored. Driven by economies of scale, the phenomenon that Anderson calls ‘print capitalism’ set about a process of linguistic and cultural standardisation of vernaculars, mostly based on the emerging metrics of the nation-state—marginalising small languages to the point where they became unviable in the modern world and standardising written national languages to official or high forms (Anderson 1983). This process of standardisation had to be rigorous and consistent, extending so far as the spelling of words—never such a large issue before—but essential in a world where text was shaped around nonlinear reading apparatuses such as alphabetical indexing. With its inexorable trend to linguistic homogenisation and standardisation, print capitalism ushered in the modern nation state, premised as it was on cultural and linguistic commonality. And so ‘correct’ forms of national languages were taught in schools; newspapers and an emerging national literature spoke to a new civically defined public; government communications were produced in ‘official’ or ‘standard’ forms; and scholarly knowledge came to be published in official versions of national languages instead of Latin. As a consequence, a trend to mass culture accompanied the rise of mass manufacture of printed text, and pressure towards linguistic homogenisation became integral to the modernising logic of the nation-state.

However rational from an economic and political point of view—realising mass literacy, providing access to a wider domain of knowledge, creating a modern democracy whose inner workings were ‘readable’—there have also been substantial losses as a consequence of these peculiarly modern processes. Phillipson documents the process of linguistic imperialism in which the teaching of literate forms of colonial and national languages does enormous damage to most of the ancestral and primarily oral languages of the world, as well as to their cultures (Phillipson 1992). Mühlhäusler traces the destruction of language ecologies—not just languages but the conditions that make these languages viable—by what he calls ‘killer languages’ (Mühlhäusler 1996).

And now, in the era of globalisation, it seems that English could have a similar effect on the whole globe to that which national languages had in their day on small languages and dialects within the territorial domains of nation-states. By virtue in part of its massive dominance of the world of writing and international communications, English is becoming a world language, a lingua mundi, as well as a common language, a lingua franca, of global communications and commerce. With this comes a corresponding decline in the world’s language diversity. At the current rate, between 60 and 90 per cent of the world’s 6,000 languages will disappear by the end of this century (Cope and Gollings 2001). To take one continent, of the estimated 250 languages existing in Australia in the late eighteenth century, two centuries later there are only 70 left possessing more than 50 speakers; perhaps only a dozen languages will survive another generation; and even those that survive will become more and more influenced by English and interconnected with Kriol (Cope 1998; Dixon 1980).

However, whereas the trend in the era of print was towards large, homogeneous speech communities and monolingual nationalism, the trend in the era of the digital may well be towards multilingualism and divergent speech communities which distinguish themselves by their peculiar manners of speech and writing—as defined, for instance, by technical domain, professional interest, cultural aspiration or subcultural fetish. None of these changes is technologically driven, or at least not simplistically so. It is not until 30 years into the history of the digitisation of text that clear signs of shape and possible consequences of these changes begin to emerge.

We will focus now on several aspects of these technological changes and changes in semiotic practice: new font rendering systems; an increasing reliance on the visual or the visually positioned textual; the emergence of social languages whose meaning functions have been signed at a level of abstraction above the meaning forms of natural language; machine translation assisted by semantic and structural markup; and a trend to customisable technologies which create the conditions for flat economies of scale, which in turn make small and divergent textual communities more viable. To denote the depth of this change, we have coined the word ‘polylingual’, foregrounding the polyvocal, polysemic potentials deeper than the simple language differences conventionally denoted by the word ‘multilingual’.

The fundamental shift in the elementary modular unit of manufacture of textual meaning—from character-level to pixel level representation—means that platforms for text construction are no longer bound by the character set of a particular national language. Every character is just a picture, and the picture elements (pixels) can be combined and recombined to create an endless array of characters. This opportunity, however, was not initially realised. In fact, quite the reverse. The first phase in the use of computers as text-bearing machines placed the Roman character set at the centre of the new information and communication technologies. Above the ‘bit’ (an electric ‘off’ or ‘on’ representing a 0 or a 1), it was agreed that arbitrary combinations of 0 s and 1 s would represent particular characters, and these characters became the foundation of computer languages and coding practices, as well as digitised written-linguistic content. The elementary unit above the ‘bit’ is the ‘byte’, using eight bits to represent a character. An eight bit (one byte) encoding system, however, cannot represent more than a theoretical 256 characters, the maximum number of pattern variations when eight sets of 0 s or 1 s are combined (27, plus an eighth stop bit). The international convention for Roman script character encoding was to became the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII), as accepted by the American Standards Association in 1963. In its current form, ASCII consists of 94 characters in the upper and lower case and punctuation marks.

Although one byte character encoding works well enough for Roman and other alphabetic scripts it won’t work for larger character sets such as the ideographic Asian languages. To represent languages with larger character sets, specialised two byte systems were created. However, these remained for all intents and purposes separate and designed for localised country and language use. Extensions to the ASCII one byte framework were also subsequently created to include characters and diacritica from languages other than English whose base character set was Roman. Non-Roman scripting systems remained in their own two-byte world. As the relationship between each character and the pattern of 0 s and 1 s is arbitrary, and as the various systems were not necessarily created to talk to each other, different computer systems were to a large degree incompatible with each other. However, to return to the fundamentals of digital text technology, pixels can just as easily be arranged in any font, from any language. Even in the case of ASCII, text fabrication seemed like just typing. Actually, it’s drawing, or putting combinations of pixels together, and there’s no reason why the pixels cannot be put together in any number of drawn combinations.

A new generation of digital technologies has been built on the Unicode universal character set (Unicode 2010). The project of Unicode is to encode every character and symbol in every human language in a consolidated two-byte system. The 94 ASCII Roman characters are now embedded in a new sixteen-bit character encoding. Here they pale into insignificance among the 107,156 characters of Unicode 5.2. These Unicode characters not only capture every character in every human language; they also capture archaic languages such as Linear B, the precursor to Ancient Greek found as inscriptions in Mycenaean ruins. Unicode captures a panoply of mathematical and scientific symbols. It captures geometric shapes frequently used in typesetting (squares, circles, dots and the like), and it captures pictographs, ranging from arrows, to international symbols such as the recycling symbol, to something so seemingly obscure as the set of fifteen Japanese dentistry symbols. The potential with Unicode is for every computing device in the world to render text in any and every language and symbol system, and perhaps most significantly for a multilingual world, to render different scripts and symbol systems on the same screen or the same page.

Unicode mixes ideographs and characters as though they were interchangeable. In fact, it blurs the boundaries between character, symbol and icon, and between writing and drawing. Ron Scollon speaks of an emerging ‘visual holophrastic language’. He derives the term ‘holophrastic’ from research on young children’s language in which an enormous load is put on a word such as ‘some’, which can only be interpreted by a caregiver in a context of visual, spatial and experiential association. In today’s globalised world, brand logos and brand names (to what language does the word ‘SONY’ belong? he asks) form an internationalised visual language. A visual holophrastic sign brings with it a coterie of visual, spatial and experiential associations, and these are designed to cross the barriers of natural language (Scollon 1999).