The Influence of the G-7 Advanced Economies and G-20 Group

Overview

When we think of the G-20 countries, whose summit took place in St. Petersburg, Russia, on September 5–6, 2013, we should think about the group of 20 finance ministers and central bankers from the 20 major economies around the world. In essence, the G-20 is comprised of 19 countries plus the European Union (EU), represented by the president of the European Council and by the European Central Bank (ECB). We begin this book discussing the importance and influence of the G-20 because, not only does this group comprise some of the most advancing economies in the world, but also because collectively these 20 economies account for approximately 80 percent of the gross world product (GWP), 80 percent of the world’s trade, which includes EUs intra-trade, and about two-thirds of the world’s population.* These proportions are not expected to change radically for many decades to come.

The G-20, proposed by the former Canadian Prime Minister Paul Martin,1 acts as a forum for cooperation and consultation on matters pertaining to the international financial system. Since its inception in September of 1999 the group has been studying, reviewing, and promoting high-level discussions of policy issues concerning the promotion of international financial stability. The group has replaced the G-8 group as the main economic council of wealthy nations.2 Although not popular with many political activists and intellectuals, the group exercises major influence on economic and financial policies around the world.

Figure 1.1 G-20 country list

The G-20 Summit was created as a response both to the financial crisis of 2007–2010 and to a growing recognition that key emerging countries (and markets) were not adequately included in the core of global economic discussion and governance. The G-20 country members are listed in Figure 1.1.

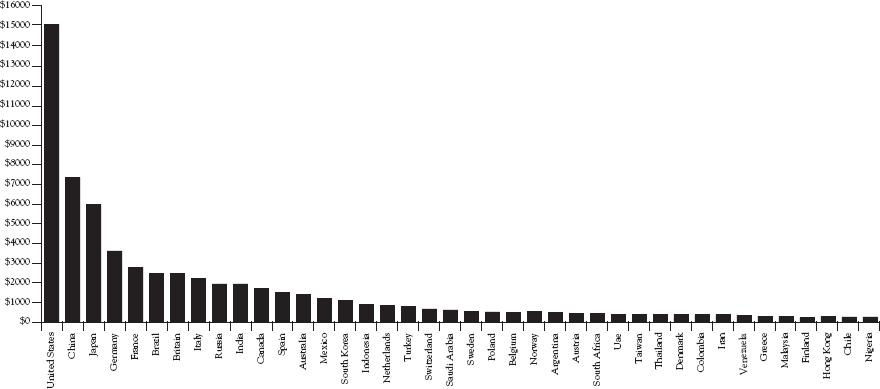

It is important to note that the G-20 members do not necessarily reflect the 20 largest economies of the world in any given year. According to the group, as defined in its FAQs, there are “no formal criteria for G-20 membership, and the composition of the group has remained unchanged since it was established. In view of the objectives of the G-20, it was considered important that countries and regions of systemic significance of the international financial system be included. Aspects such as geographical balance and population representation also played a major part.”3 All 19-member nations, however, are among the top 30 economies as measured in gross domestic product (GDP) at nominal prices according to a list published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF)4 in April 2013. That being said, the G-20 list does not include some of the top 30 economies in the world as ranked by the World Bank5 and depicted in Figure 1.2, such as Switzerland (19th), Thailand (30th), Norway (24rd), and Taiwan (29th), despite the fact these economies rank higher than some of the G-20 members. In the EU, the largest economies are Spain (13th), the Netherlands (18th), Sweden (22nd), Poland (24th), Belgium (25th), and Austria (28th). These economies are ranked as part of the EU though, and not independently.

Figure 1.2 World Bank top 40 countries by GDP

Asian economies, such as China (2nd) and India (10th), are expected to play an important role in global economic governance, according to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), as the rise of emerging market economies are heralding a new world order. The G-20 would likely become the global economic steering committee. Furthermore, not only have Asian countries been leading the global recovery following the great recession, but key indicators also suggest the region will have a greater presence on the global stage, especially considering the latest advances in GDP for countries such as Thailand and the Philippines. These trends are shaping the G-20 agenda for balanced and sustainable growth through strengthening intraregional trade and stimulating domestic demand.6

The G-7 and G-20 Group Influence in the Global Economy

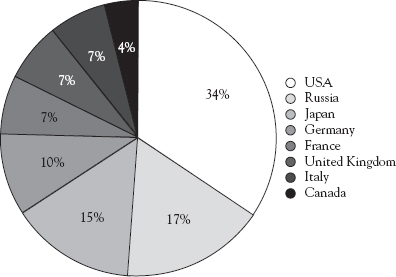

Prior to the G-20 enjoying the influence it has today in global economic policy making, the group of advanced economies, the G-8 group, consisting of the United States (U.S.), Canada, France, the United Kingdom (UK), Italy, Germany, Japan, and Russia, was a leading global economic policy forum. Figure 1.3 illustrates the breakdown of the G-8 countries by population. The U.S. population is about 300 million people, which is roughly a third of the population of all of the G-8 countries combined-—equal to Japan and Russia combined, and to Germany, France, Italy, Canada, and the UK combined. Russia has been removed from the G-8 group which now is referred to as the G-7.

As the world economy continues to be increasingly integrated, the need for a global hub where the world economy issues and challenges could converge is a major necessity. In the absence of a complete overhaul of the United Nations (UN) and international financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, the G-20 is the only viable venue to mitigate the interests of these leading nations. Since the G-20 group has overshadowed the G-7, it has become a major forum for global decision-making, central to designing a pathway out of the worst global financial crisis in almost a century. It did so by effectively coordinating the many individual policies adopted by its members and thus establishing its importance in terms of crisis management and coordination during an emergency.

Figure 1.3 List of G-8 Countries by power of influence

Source: CIA World Factbook

The G-20 has failed, thus far, to live up to expectations as a viable alternative to the G-7, although it continues to be at the heart of global power shifts, particularly to emerging markets. Efforts to reform the international financial system have produced limited results. It has struggled to deliver on its 2010 summit promises on fiscal consolidation and banking capital, while the world watches the global finance lobbyists repeatedly demonstrate their ability to thwart every G-20’s attempt to regulate financial flows, despite the volatility associated with the movement of large amounts of short-term funds. Larger economies, such as Germany and Spain have been concerned with the lack of effective regulation of financial flows. Emerging markets such as the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) countries and the CIVETS (Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey, and South Africa*) countries are scrambling to deflect the exportation of inflation from these advanced G-7 economies into their domestic economies. Countries such as Iceland, the UK, and Ireland, whose banking systems had to undergo painful recapitalization, nationalization and restructuring to return to profitability after the financial crisis broke, also share these concerns.

In the words of Ian Bremmer,* in his book titled Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World,7 when reflecting on the then newly created G-20 group, “I found myself imagining an enormous poker table where each player guards his stack of chips, watches the nineteen others, and waits for an opportunity to play the hand he has been dealt. This is not a global order, but every nation for itself. And if the G-7 no longer matters and the G-20 doesn’t work, then what is this world we now live in?”†

According to Bremmer, we now are living in a time where the world has no global leadership since, he argues, the United States can no longer provide such leadership to the world due to its “endless partisan combat and mounting federal debt.”8 He also argues that Europe can’t provide any leadership either as debt crisis is crippling confidence in the region, its institutions, and its future. In his view, the same goes for Japan, which is still recovering from a devastating earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown, in addition to the more than two decades of political and economic malaise. Institutions like the UN Security Council, the IMF, and the World Bank are unlikely to provide real leadership because they no longer reflect the world’s true balance of political and economic power. The fact is, a generation ago the G-7 were the world’s powerhouses, the group of free-market democracies that powered the global economy. Today, they struggle just to find their footing.

In Bremmer’s view, “The G-Zero phenomenon and resulting lack of global leadership have only intensified—and analysts from conservative political scientist Francis Fukuyama to liberal Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz have since written of the G-Zero as a fact of international life.”9 “The G-Zero,” Bremmer continues, “won’t last forever, but over the next decade and perhaps longer, a world without leaders will undermine our ability to keep the peace, to expand opportunity, to reverse the impact of climate change, and to feed growing populations. The effects will be felt in every nation of the word—and even in cyberspace.”10

Coping with Shifting Power Dynamics and a Multipolar World

In the past decade, the emerging markets have been growing at a much faster pace than the advanced economies. Consequently, participation in the global GDP, global trade, and foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly in the global financial markets, has significantly increased as well. Such trends, according to a study conducted by the Banco de Espana’s analysts Orgaz, Molina, and Carrasco,11 are expected to continue for the next few years. The global economic crises has fostered relevant changes to the governance of the global economy, particularly with the substitution of the G-7 with the G-20 group as a leading international forum in the development of global economic policies.

The G-20’s failure to effectively regulate global financial flows has led to efforts to reclaim national sovereignty through so-called host or home-country financial regulations, as national legislative bodies seek control over financial flows. The impetus for both can be found in the changing global order as it moves toward greater global balance.

For many decades various other groups, such as the G-7, the Non-aligned Movement, India, Brazil, South Africa (IBSA), and the BRICS, to name the main ones, have been applying some informal pressure, largely reflecting the continued north-south or (advanced versus emerging markets) divide into global geopolitics and wealth. Although financial analysts and policy makers in the advanced economies tend to view the G-20 as a venue to build and extend the outreach of global consensus on their policies, such expectations have been changing due to the establishment of a loose coalition with a distinctly contrarian view on many global issues. This is particularly true in regard to the role of the state in development and on finance.

This loose coalition, which has become more prominent since the global financial crises of 2008, is spearheaded by the BRICS (the “S” is for South Africa), led by China. While Chapter 7 provides a more in-depth discussion on the role of the BRICS in this process, for now it is important to note how the BRICS countries are able to apply pressure on the G-20 group, particularly to advanced economies.

The BRICS cohort countries within the G-20 have a combined GDP three times smaller than that of the G-7. Nonetheless, the gap between the two decreases every year and is expected to disappear within the next two decades, if not sooner. Even more importantly, most of the economic growth within the G-20 is coming from the BRICS (and other emerging and so called “frontier” markets) rather than from the advanced economies (the G-7). Hence, while there are many other geopolitical dynamics playing out within the G-20, we believe the most important play at the moment and in the next two decades is a battle for strategic positioning by the advanced economies versus the emerging markets, who are led by the BRICS. Even more important is to watch as the BRICS jockey for support from other G-20 members such as Indonesia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. While some allegiances may appear obvious, economic and political benefits often pull in opposite directions, leaving policy makers with difficult choices to make.

In order for the G-20 countries to continue to build on their collective success in the management of the global financial crisis, it is imperative for them to place more emphasis on global trade and financial reform. These elements are at the core of global trade and economic governance. Unfortunately, advanced economies, particularly in North America and Europe, are heading in a different direction than the emerging ones, particularly the BRICS, as a result of the shifting power dynamics in an increasingly multipolar world. In the past decade China prominently has exercised this shift.

Such shifting of power dynamics, or the fight to control it, is perhaps most evident in the efforts toward exclusive trade agreements in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, such as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), where discussions began in July of 2013 between the United States and Europe. Similarly, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) also discussed collaborating with eleven other countries, including Japan.

TTIP’s main objective is to drive growth and create jobs by removing trade barriers in a wide range of economic sectors, making it easier to buy and sell goods and services between the EU and the United States. A research study conducted by the Centre for Economic Policy Research, in London-UK, titled Reducing Trans-Atlantic Barriers to Trade and Investment: An Economic Assessment,12 suggests that TTIP could boost the EU’s economy by €120 billion euros (US$197 billion), while also boosting the U.S. economy by €90 billion euros (US$147.75 billion) and the rest of the world by €100 billion euros (US$164.16 billion).

The success of TTIP and TPP could undermine the future viability of the World Trade Organization (WTO) as a global trade forum, such as the Doha Round. Although not isolated, China is party to neither group. The unspoken concern is that the two agreements are aimed at ensuring continued Western control of the global economy by building a strong relationship between the euro and the dollar while constraining and containing a growing and increasingly assertive China.

The TPP, on the other hand, suffers from a severe lack of transparency, as U.S. negotiators are pushing for the adoption of copyright measures far more constraining than currently required by international treaties, including the polemic Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA). The treaty, while also attempting to rewrite global rules on intellectual property enforcement is nonetheless, a free trade agreement. At the time of this writing (fall of 2013), the ACTA is being negotiated by twelve countries. As depicted in Figure 1.4, these countries include the United States, Japan, Australia, Peru, Malaysia, Vietnam, New Zealand, Chile, Singapore, Canada, Mexico, and Brunei Darussalam.

Figure 1.4 The Trans-Pacific Partnership eleven member countries

The Impact of Indebtedness of the Advanced Economies on Emerging Markets

In September of 2013 Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper vehemently urged G-20 leaders not to lose sight of the vital importance of reining in debt across the group after several years of deficit-fueled stimulus spending. He stuck to the common refrain in the face of weak recoveries among member countries, including Canada. Specifically referring to the risk of accumulating public debt points, Mr. Harper also acknowledged that recoveries from the financial crisis, that started five years ago, have been disappointing because many of the advanced economies continue to grapple with high unemployment, weak growth, and rising income inequality.

Since the economic crisis of 2008, the United States and its financial analysts and politicians have been very vocal with ideas of fiscal cliffs, debt ceiling, and defaults. To some extent, the situation is not much different among the EU block. Debt to GDP ratios and deficit figures have been touted as omens of financial failure and public debt has been heralded as the harbinger of an apocalypse. The truth of the matter is that many countries around the world, especially in the emerging markets during the 1970’s and 1980’s, had experienced large amounts of debt, often in excess of 100 percent of GDP, as advanced economies are experiencing right now. Nonetheless, what is different this time is that while emerging markets had most of their debt in external markets and denominated in foreign currencies, they also had differing structures and institutions than the advanced economies.

The last quarter of the 19th century was a period of large accumulation of debt due to widespread infrastructure building in advanced economies around the globe, mainly due to new innovations at the time, such as the railroads. As these economies expanded and continued to invest in infrastructure, much debt was created. The same was true during World War I (WWI) reflecting the military spending taken on during the wartime period, and immediately after that during the reconstruction period. Another period of large debt was amassed during and post World War II (WWII). In this case, some of these debt levels started to build a bit earlier, as a result of the great recession, but most were the result of WWII. Finally, we have the period where most governments and policymakers of advanced economies struggled to move from the old economic systems to the current one. During these four different periods, most advanced economies experienced 100 percent or more debt to GDP ratios at least one or more times. The dynamics of debt to GDP ratios are in fact very diverse; their effects are widely varied and based on a variety of factors. Take for example the case of the UK in 1918, the United States in 1946, Belgium in 1983, Italy in 1992, Canada in 1995, and Japan in 1997. All of these countries went through a process of indebtedness, each with a full range of outcomes.

In the case of UK, policymakers tried to return to the gold standard at pre-WWI levels to restore trade, prosperity and prestige, and to pay off as much debt, as quickly as possible to preserve the image of British good credit. They sought to achieve these goals through policies that included thrift saving. Their efforts did not have the intended effects. The dual pursuit of going back to a strengthened currency from a devalued one, along with the pursuit of fiscal austerity seemed to be a deciding factor in the failure. Trying to go back to the gold standard made British exports less attractive than those of surrounding countries who had not chosen this path. Consequently, exports were low, and to combat this, British banks kept interest rates high. Those high interest rates meant that the debt the country was trying to pay off increased in value and the country’s slow growth and austerity did not give them the economic power to pay off the debts as they wanted. In an effort to maintain integrity and the image of “Old Faithful Britain,” the policymakers ruined their chances for a swift recovery.

In the United States, policymakers chose not to control inflation, and kept a floor on government bonds. Over time, these ideas changed and bond protection measures were lifted. In turn, the government’s ability to intervene in inflation situations changed. The United States experienced rapid growth during this time, partially due to high levels of monetary inflation, but that inflation, even though it would “burst” at the start of the Korean War, allowed the United States to pay off much of its debt. This, coupled with the floor on U.S. bonds, created a favorable post high debt level scenario.

Japan’s initial response to its debt situation was the cutting of inflation rates and the introduction of fiscal stimulus programs. This response did not have the intended effect, as currency appreciated. The underlying issues that had helped to cause the high debt to GDP ratios were still present, and would be until 2001 when the government committed to boosting the country’s economy through policy and structure changes. Japan still has a very high debt to GDP ratio, but the weaknesses in the banking sector have been fixed and the country seems to be on a path to recovery.

Italy’s attempts at fiscal reform included changes to many social programs, including large cuts to pension spending. The reforms, though, were not implemented quickly enough and did not address enough of the demographic issues to make a large impact. It wasn’t until later that further fiscal consolidation was achieved. It is important to note that Italy’s GDP growth did not help reduce debt during this period, and thus remained very weak.

Belgium used similar kinds of fiscal consolidation plans to those of Italy, but those plans were more widespread and implemented at a more rapid pace. The relative success of these initial fiscal consolidations helped to further growth and reduction of the debt to GDP ratio. These plans also fueled another round of successful consolidation when the country needed it to enter the EU.

Canada’s initial reaction included fiscal changes such as tax hikes and spending cuts; a plan of austerity. The plan failed and deepened the country’s debt. The second wave of fiscal consolidation was aimed at fixing some of the structural imbalances that had caused the debt levels in the first place. It worked, helped along by the strengthening of economic conditions in surrounding countries, mainly the United States. The Canadian example shows that external conditions are just as important for success as the policies or missions taken on within the country.

From all of these examples, we have an idea of the impact that advanced economies have on each other as well as on emerging markets. In an intertwined global economy, imbalances in one country’s economy impact virtually every other country in the world. The extent of the impact and mitigation will always vary depending on internal and external market conditions, as well as policy development. Similarly solutions, like U.S. inflation adjustments, may not work today or in another country. For instance, if we take the global financial crises that started in 2008, allowing inflation levels to rise could pose risks to financial institutions, and could lead to a globally less-integrated financial system.

The most pertinent example would appear to be the kind of fiscal policies used in Canada, Belgium, and Italy. All three countries attempted to achieve low inflation, but their other policy reforms varied in success. More permanent fiscal changes tend to create more prominent and lasting reductions to debt levels. Even then, a country must be exposed to an increase in external demands if the country’s recovery is to mirror the successful cases cited earlier. Consolidation needs to be implemented alongside measures to support growth and changes that address structural issues. The final factor to note is that even with a successful plan, the effects of the plan take time. Debt level reductions will not be quick in today’s global and interwoven economies.

The Crisis Isn’t Over Yet

Advanced economies, specifically in the EU and the United States are still dealing with the global financial crises that started in 2008. Despite the positive rhetoric of policy makers and governments, on both sides of the Atlantic, Harvard economist Carmen Reinhart feels that the crisis is not yet over. She alleges that both the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) are keeping interest rates low to help governments out of their debt crises. In the past and as shown in the historial examples cited earlier, central banks are bending over backwards to help governments of advanced economies to finance their deficits.

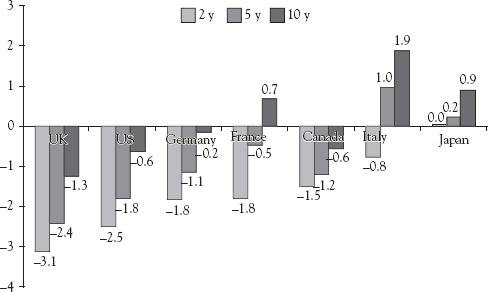

As was mentioned earlier in this chapter, after WWII, all countries that had a big debt overhang relied on financial repression to avoid an explicit default, and governments imposed interest rate ceilings for government bonds. Liberal capital-market regulations and international capital mobility at the time reached their peak prior to WWI under the gold standard. But, the Great Depression followed by WWII, put the final nail in the coffin of laissez-faire banking.* It was in this environment that the Bretton Woods arrangement, of fixed exchange rates and tightly controlled domestic and international capital markets, was conceived. The result was a combination of very low interest rates and inflationary spurts of varying degrees across the advanced economies. The obvious results were real interest rates—whether on treasury bills, central bank discount rates, deposits or loans—that were markedly negative during 1945 and 1946. For the next 35 years, real interest rates in both advanced and emerging economies would remain consistently lower than during the eras of free capital mobility, including before and after the financial repression era. Ostensibly, real interest rates were, on average, negative. The frequency distributions of real rates for the period of financial repression (1945–1980) and the years following financial liberalization highlight the universality of lower real interest rates prior to the 1980s and the high incidence of negative real interest rates in the advanced economies. (See Figure 1.5.) Reinhart and Sbrancia13 (2011) demonstrate a comparable pattern for the emerging markets.

Nowadays, however, monetary policy is doing the job, but unlike many policy makers would like us to believe, these economies are seldom able to break out of debt. Money to pay for these debts must come from somewhere. Reinhart (2011) * believes those advanced economies in debt today must adopt a combination of austerity to restrain the trend of adding to the stack of debt and higher inflation. This is effectively a subtle form of taxation and consequently will cause a depreciation of the currency and erosion of people’s savings.

Figure 1.5 Real interest rates frequency distributions: Advanced economies, 1945–2011

We do not advocate for or against current central bank policies in these economies; this is not the premise of this book. Advanced economies, however, do need to deal with their debt as these high debt levels prevent growth and freeze the financial system and the credit process. As long as emerging markets continue to depend heavily on the exports of these advanced economies, they too will be negatively impacted. We believe, however, that the debt of the United States and the EU, in particular, affects the global economy significantly. The current central bank policies are not effective; money is being transferred from responsible savers to borrowers via negative interest rates.

In essence, when the inflation rate is higher than the interest rates paid on the markets, the debts shrink as if by magic. As dubbed by Ronald McKinnon14 (1973), the term financial repression describes various policies that allow governments to capture and under-pay domestic savers. Such policies include forced lending to governments by pension funds and other domestic financial institutions, interest-rate caps, capital controls, and many more. Typically, governments use a mixture of these policies to bring down debt levels, but inflation and financial repression usually only work for domestically held debt. The eurozone is a special hybrid case. The financial repression implemented by advanced economies is designed to avoid an explicit default on the debt. Unfortunately, this is not only ineffective in the long run, but also unjust to responsible taxpayers. Eventually public revolts may develop, such as the ones already witnessed in Greece and Spain. Governments could write off part of the debt, but evidently no politician would be willing to spearhead such write-offs. After all, most citizens do not realize their savings are being eroded and that there is a major transfer of wealth taking place. Undeniably, advanced economies around the world have a problem with debt. In the past, several tactics, including financial repression, have dealt with such problems, and now it seems, debt is resurging again in the wake of the global and eurozone crises.

Financial repression, coupled with a steady dose of inflation, cuts debt burdens from two directions. First off, the introduction of low nominal interest rates reduces debt-servicing costs. Secondly, negative real interest rates erode the debt-to-GDP ratio. In other words, this is a tax on savers. Financial repression also has some noteworthy political-economic properties. Unlike other taxes, the “repression” tax rate is determined by financial regulations and inflation performance, which are obscure to the highly politicized realm of fiscal measures. Given that deficit reduction usually involves highly unpopular expenditure reductions and/or tax increases of one form or another, the relatively stealthier financial repression tax may be a more politically palatable alternative for authorities faced with the need to reduce outstanding debts. In such an environment, inflation, by historic standards, does not need to be very high or take market participants entirely by surprise.

Unlike the United States, which is resorting to financial repression, Europe is focusing more on austerity measures; despite the fact inflation is still at a low level. Notwithstanding, debt restructuring, inflation, and financial repression, are not a substitute for austerity. All these measures reduce a country’s existing stock of debt, and as argued by Reinhart,15 policy makers need a combination of both to bring down debt to a sustainable level. Although the United States is highly indebted, an advantage it has against all other advanced economies is that foreign central banks are the ones holding most of its debts. The Bank of China and the Bank of Brazil, two leading BRICS emerging economies, are not likely to be repaid. It does not mean the United States will default. We don’t know that, no one does. It actually doesn’t have to explicitly default since if you have negative real interest rates, a transfer from China and Brazil, the effect on the creditors is the same, as well as other creditors to the United States.

The real risk here for the United States, EU, and other advanced economies is that creditors may decide not to play along anymore, which would cause interest rates on American government bonds to climb. This act would be similar to the major debt crisis of Greece and Iceland, and what was happening in Spain until the ECB intervened. We believe the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, and likely the ECB, is prepared to continue buying record levels of debt for as long as it takes to jump-start the economy. To counter the debasement of the dollar, China’s central bank is likely to continue to buy U.S. treasury bonds in a constant attempt to stop the export of inflation from the United States into its economy and by preventing the renminbi from appreciating. In an attempt to save their economies from indebtedness, advanced economies are raging what Jim Rickards calls a currency war16 against the emerging markets and the rest of the world.

We believe the combination of high public and private debts in the advanced economies and the perceived dangers of currency misalignments and overvaluation in emerging markets facing surges of capital infglows, are causing pressures toward currency intervention and capital controls, interacting to produce a home-bias in finance, and a resurgence of financial repression. At present, we find that emerging markets, especially the BRICS, are being forced to adopt similar policies as the advanced economies—hence the currency wars—but not as a financial repression, but more in the context of macro-prudential regulations.

Advanced economies are developing financial regulatory measures to keep international capital out of emerging economies, and in advanced economies. Such economic controls are intended to counter loose monetary policy in the advanced economies and discourage the so-called hot money,* while regulatory changes in advanced economies are meant to create a captive audience for domestic debt. This offers advanced and emerging market economies common ground on tighter restrictions on international financial flows, which borderlines protectionism policies. More broadly, the world is witnessing a return to a more tightly regulated domestic financial environment, i.e. financial repression.

We believe advanced economies are imposing a major strain on global financial markets, in particular emerging economies, by exporting inflation to those countries. Because governments are incapable of reducing their debts, central banks are pressured to get involved in an attempt to resolve the crisis. Reinhart argues that such a policy does not come cheap, and those responsible citizens and everyday savers, will be the ones feeling the consequences of such policies the most. While no central bank will admit it is purposely keeping interest rates low to help governments out of their debt crises, banks are doing whatever they can to help these economies finance their deficits.

The major danger of such a central bank policy, which can be at first very detrimental to emerging markets that are still largely dependent on consumer demands from advanced economies, is that it can lead to high inflation. As inflation rises among advanced economies, it is also exported to emerging market economies. In other words, as the U.S. dollar and the euro debases and loses buying power, emerging markets experience an artificial strengthening of their currency, courtesy of the U.S. Federal Reserve and the ECB. In turn, this causes the prices of goods and services to also increase and hurts exports in the process.

Figure 1.5 strikingly shows that real export interest rates (shown for treasury bills) for the advanced economies have, once again, turned increasingly negative since the outbreak of the crisis in 2008. Real rates have been negative for about one half of the observations, and below one percent for about 82 percent of the observations. This turn to lower real interest rates has materialized despite the fact that several sovereigns have been teetering on the verge of default or restructuring. Indeed, in recent months negative yields in most advanced economies, the G-7 countries, have moved much further outside the yield curve, as depicted in Figure 1.6.

Figure 1.6 G-7 real government bond yields, February 2012

No doubt, a critical factor explaining the high incidence of negative real interest rates in the wake of the crisis is the aggressive expansive stance of monetary policy, particularly the official central bank interventions in many advanced and emerging economies during this period.

At the time of this writing, in the fall of 2013, the level of public debt in many advanced economies is at their highest levels, with some economies facing the prospect of debt restructuring. Moreover, public and private external debts, which we should not ignore, are typically a volatile source of funding, are at historic highs. The persistent levels of unemployment in many advanced economies also are still high. These negative trends offer further motivation for central banks and policy makers to keep interest rates low, posing a renewed taste for financial repression. Hence, we believe the final crisis isn’t over yet. The impact that advanced economies are imposing on emerging markets, and its own economies, is only the tip of a very large iceberg.

* G-20 Membership from the Official G-20 website at www.g20.org

* It is important to note that although South Africa is grouped with the CIVETS bloc, it also has been aggregated to the BRIC bloc, where it is more likely to belong.

* Bremmer is the president of the Eurasia Group, the world’s leading global political risk research and consulting firm.

† Emphasis is ours.

* An economic theory from the 18th century that is strongly opposed to any government intervention in business affairs.

* Ibidem.

* Capital that is frequently transferred between financial institutions in an attempt to maximize interest or capital gain.