Overview

More than half a decade has passed since the financial crisis hit, traversing the global economy very rapidly, confirming just how interconnected the world has become as ideas, information, capital, and new technologies have streamed across borders with increasing ease. Nevertheless, the lack of sustained financial crisis response has made it clear just how fractured the international political landscape has become, as advanced and emerging economies’ diverging interests make global coordination ever more difficult. Hence, despite sustained globalization, and in some cases because of it, we are seeing a growing vacuum of global leadership, as well as traditional geopolitical risks, which consequently are on the rise.

This chapter attempts to address key global issues for tomorrow that demand our attention today. It provides an overview of many of the most volatile, significant, and misunderstood developments reshaping the global geopolitical landscape, from the growing global vulnerability of public and private institutions to the increasing impact of public opinion and protest.

As James Rickards argues1 the world is amidst a full-blown currency war, and assuming this is true, there are several undercurrents between advanced economies and emerging markets to which we need to be attentive, beginning with the United States-China dynamics, the relations between China and the Russian Federation, and more broadly the rest of Asia. We also attempt to address the significant shifts in the Middle East, and the unconventional energy revolution in North America that is primed to reshape global energy markets and the world’s balance of power. The central focus of this chapter, aside from developing awareness that global economies are at war, is the fact that the world, more than ever before, is constantly and rapidly changing, and international business professionals must seek guidance on how to understand the key players in the evolving global landscape.

Such trends have gained momentum in shaping global trade, especially among advanced economies and emerging markets, leading to a host of new challenges to policymakers worldwide, as well as international traders and multinational corporations. In a world where the international agenda is coming undone, local and shorter-term challenges take precedence for policymakers and international business leaders. That itself is an issue, as longer-term risks go unaddressed and loom larger. Furthermore, we have seen an increased vulnerability of elites, as a host of new voices, whether from the voting booth in advanced economies, populist parties, growing middle classes in emerging markets, or through new technologies, have put added strain on leaders who are increasingly takers rather than makers of policy.

Economies at War

Since 2010, government officials from the G-7 economies have been very concerned with the potential escalation of a global economic war. Not a conventional war with fighter jets, bullets, and bombs, but rather, a “currency war.” Finance ministers and central bankers from advanced economies worry that their peers in the G-20, which also includes several emerging economies, may devalue their currencies to boost exports and grow their own economies at their neighbors’ expense.

Brazil led the charge, being the first emerging economy to accuse the United States of instigating a currency war in 2010, when the U.S. Federal Reserve bought piles of bonds with newly created money. From a Chinese perspective, with the world’s largest holdings of U.S. dollar reserves, a U.S. lead currency war based on dollar debasement is an American act of default to its foreign creditors. So far the Chinese have been more diplomatic, but their patience is waning.

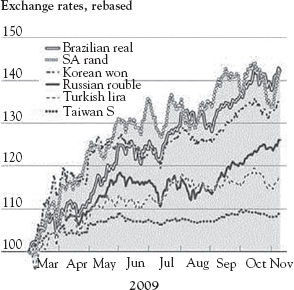

These two countries are not alone, as depicted in Figure 5.1. Several other emerging markets, such as Saudi Arabia, Korea, Russia, Turkey, and Taiwan also have been impacted by a weak dollar. Quantitative easing (QE) made investors flood emerging markets with hot money in search of better returns, which consequently lifted their exchange rates. But Brazil was not alone, as Japan’s prime minister, Shinzo Abe, also has reacted to the QEs in the United States and pledged bold monetary stimulus to restart growth and vanquish deflation in the country.

Figure 5.1 Emerging market currencies inflated by weak dollar

Source: Thompson Reuters Datastream

As advanced economies, like the three largest world economies—United States, China and Japan respectively—try to kick-start their sluggish economies with ultra low interest rates and sprees of money printing, they are putting downward pressure on their currencies. The loose monetary policies are primarily aimed at stimulating domestic demand, but their effects spill over into the global currency world.

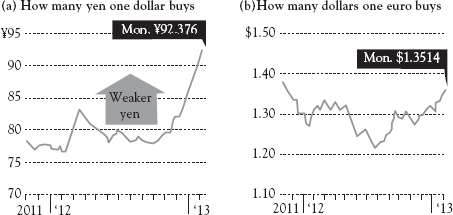

Japan faces charges that it is trying to lower the value of its currency, the yen, to stimulate its economy and get an edge over other countries. The new Japanese government is trying to get Japan, which has been in recession, moving again after a two-decade bout of stagnant growth and deflation. Hence, it embarked on an economic course it hopes will finally jump-start the economy. The government coerced the Bank of Japan to accept a higher inflation target, which-triggered speculation that the bank will create more money. The prospect of more yen in circulation has been the main reason behind the yen’s recent falls to a 21-month low against the dollar and a near three-year record against the euro.

Figure 5.2 Central banks in the United States and Japan has flooded their economies with liquidity

Source: WSJ Market Data Group

Since Abe called for a weaker yen to bolster exports, the currency has fallen by 16 percent against the dollar and 19 percent against the euro. As the yen falls, its exports become cheaper, and also those of its neighbors, such as of Asian neighbors South Korea and Taiwan. At the same time, the exports for those countries further afield in Europe, become relatively more expensive. As depicted in Figure 5.2, central banks in the United States and Japan have flooded their economies with liquidity since mid-2012 and into 2013, causing the both the yen and the dollar to weaken against other major currencies.

In our opinion, common sense could prevail, putting an end to the dangerous game of beggar (and blame) thy neighbor. After all, the IMF was created to prevent such races, and should try to broker a truce among foreign exchange competitors. The critical issues in the United States, as well as China and Japan, stem from ineffective public policy, but also a failed and destructive economic policy. These policy errors are directly responsible for the opening salvos of the currency war clouds now looming overhead.*

So far, Europe has felt the most impact of the falling yen. At the height of the eurozone’s financial crisis in 2012, the euro was worth US$1.21, which was potentially benefitting big exporters like BMW, AUDI, Mercedes, or Airbus. However, at the time of this writing in December 2013, the euro is at US$1.38 even though the eurozone is still the laggard of the world economy.

Across the 17-strong euro area a recovery has been underway following a double-dip recession lasting 18 months, but it is a feeble one. For 2013 as a whole, GDP still will continue to fall by 0.4 percent (after declining by 0.6 percent in 2012), but it is expected to rise by 1.1 percent in 2014.2 A rise in the value of the euro has to do with the diminishing threat of a collapse of the currency, will do little to help companies in the eurozone—and barely help it regrow.

Chinese policymakers reject the conventional thinking proposed by advanced economies. How about the yen’s extraordinary rise over the last 40 years, from JPY360 against the dollar at the beginning of the 1970s to about JPY102 today?* Not to mention that despite this huge appreciation, Japan’s current account surplus has only gotten bigger, not smaller. They also could argue that the United States’ prescription for China’s economic rebalancing, a stronger currency, and a boost to domestic demand was precisely the policy followed by the Japanese in the late-1980s, leading to the biggest financial bubble in living memory and the 20-year hangover that followed.

Furthermore, the demand by the United States, which is backed by the G-7 to revalue the renminbi, in our view, is a policy of United States default. During the Asian crisis in 1997–98, advanced economies, under the auspices of the IMF, insisted that Asian nations, having borrowed so much, should now tighten their belts. Shouldn’t advance economies be doing the same? In addition Chinese manufacturing margins are so slim that significant change in exchange rates could wipe them out and force layoffs of millions of Chinese. As it is, labor rates are already climbing in China, further squeezing margins. Lastly, a revaluation of the yuan would only push manufacturing to other cheaper emerging markets, such as Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Bangladesh, and other lower paying nations without improving the advanced economies trade deficits.

Some G-7 policymakers believe these criticisms grumbles are overdone; arguing that the rest of the world should praise the United States and Japan for such monetary policies, suggesting the eurozone should do the same. The war rhetoric implies that the United States and Japan are directly suppressing their currencies to boost exports and suppress imports, which in our view is a zero-sum game, which could degenerate into protectionism and a collapse in trade.

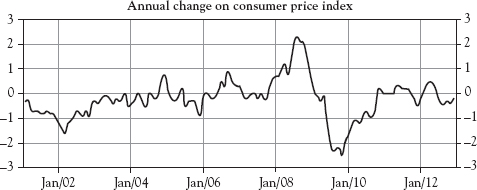

These countries, however, do not believe such a currency devaluation strategy will threaten trade. Rather, their belief seems to be that as central banks continue to lower their short-term interest rate to near zero, exhausting their conventional monetary methods in the process, they must employ unconventional methods, such as QE, or try to convince consumers that inflation will arise. The goal is to lower real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. If so, inflation should be rising in the United States and in Japan, which according to Figure 5.3, it is.

Over the past decade, Japan has seen the consumer price index (CPI) for most periods hover just below the zero-percent inflation line. (See Figure 5.3.) The notable exceptions were in 2008, when inflation rose as high as two percent, and in late 2009, when prices fell at close to a two percent rate. The rise in inflation coincided with a crash in capital spending. The worst period of deflation preceded an upturn. Of course, the graph does not provide enough data to conclude causal effects, but it seems, however, that the relationship between growth and Japan’s mild deflation may be more complicated than the Great Depression-inspired deflationary spiral narrative suggests. The principal goal of this policy was to stimulate domestic spending and investment, but lower real rates usually weaken the currency as well, and that in turn tends to depress imports. Nevertheless, if the policy is successful in reviving domestic demand, it will eventually lead to higher imports.

Figure 5.3 Japan’s inflation rate has been climbing since 2010 as a result of economic stimulus

Source: Trading Economics,3 Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs & Communications

At least that’s the idea behind the argument. The IMF concluded that the United States’ first rounds of QE boosted its trading partners’ output by as much as 0.3 percent. The dollar did weaken, but that became a motivation for Japan’s stepped-up assault on deflation. The combined monetary boost on opposite sides of the Pacific has been a powerful elixir for global investor confidence, if anything, to move hot-money emerging markets where the interests were much higher than in advanced economies.

The reality is that most advanced economies have overconsumed in recent years. It has too much debt. Rather than dealing with the debt—living a life of austerity, accepting a period of relative stagnation—these economies want to shift the burden of adjustment onto its creditors, even when those creditors are relatively poor nations with low per capita incomes. This is true not only for China but also for many other countries in Asia and in other parts of the emerging world. During the Asian crisis in 1997–98, Western nations, under the auspices of the IMF, insisted that Asian nations, having borrowed too much, should tighten their belts. However, the United States doesn’t seem to think it should abide by the same rules. Better to use the exchange rate to pass the burden onto someone else than to swallow the bitter pill of austerity.

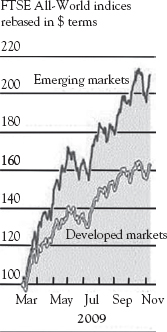

Meanwhile, European policymakers, fearful that their countries’ exports are caught in this currency war crossfire, have entertained unwise ideas such as directly managing the value of the euro. While the option of generating money out of thin air may not be available to emerging markets, where inflation tends to remain problematic, limited capital controls may be a sensible short-term defense against destabilizing inflows of hot money. Figure 5.4 illustrates how the inflows of hot-money leaving advanced economies in search of better returns on investments in emerging markets have caused these markets to significantly outperform advanced (developed) markets.

Figure 5.4 In 2009 emerging markets significantly outperformed advanced (developed) economies

Source: FTSE All-World Indices

Currency War May Cause Damage to Global Economy

As more countries try to weaken their currencies for economic gain, there may come a point where the fragile global economic recovery could be derailed and the international financial system thrown into chaos. That’s the reason financial representatives from the world’s leading 20 industrial and developing nations spent most of their time during the G-20 summit in Moscow in September 2013.

In September 2011, Switzerland took action to arrest the rise of its currency, the Swiss franc, when investors, looking for somewhere safe to store their cash from the debt crisis afflicting the 17-country eurozone, saw in the Swiss franc the traditional instrument to fulfill that role. The Swiss intervention was viewed as an attempt to protect the country’s exporters.

In our view, policymakers are focusing on the wrong issue. Rather than focus on currency manipulation, all sides would be better served to hone in on structural reforms. The effects of that would be far more beneficial in the long run than unilateral United States, China, or Japan currency action, and more sustainable. The G-20 should focus on a comprehensive package centered on structural reforms in all countries, both advanced economies and emerging markets. Undeniably, exchange rates should be an important part of that package. For instance, to reduce the U.S. current-account deficits, Americans must save more. To continue to simply devalue the dollar will not be sufficient for that purpose. Likewise, China’s current-account surpluses were caused by a broad set of domestic economic distortions, from state-allocated credit to artificially low interest rates. Correcting China’s external imbalances requires eliminating these distortions as well.

As long as policymakers continue to focus on currency exchange issues, the volatility in the currency markets will continue to escalate. Indeed, it has become so worrisome that the G-7 advanced economies have warned that volatile movements in exchange rates could adversely hit the global economy. Figure 5.5 provides a broad view (rebased at 100 percent on August 1st, 2008) of main exchange rates against the dollar.

Figure 5.5 Exchange rates against the dollar

Source: Bloomberg

When it became clear that Shinzo Abe with his agenda of growth-at-all-costs would win Japan’s elections, the yen lost more than 10 percent against the dollar and some 15 percent against the euro. In turn, the dollar dropped to its lowest level against the euro in nearly 15 months. These monetary debasement strategies are adversely impacting and angering export-driven countries such as Brazil, and many of the BRICS, ASEAN, CIVETS, and MENA blocs. But these strategies also are stirring the pot in Europe. The eurozone has largely remained quiet regarding monetary stimulus and now finds itself in the invidious position of having a contracting economy and a rising currency.

These currency moves have shocked BRICS countries as well as other emerging-market economies, including Thailand. The G-20 is clearly divided between the advanced economies, including the UK, United States, Japan, France, Canada, Italy, and Germany, and emerging countries such as Russia, China, South Korea, India, Brazil, Argentina, and Indonesia. Top leaders of Russia, South Korea, Germany, Brazil, and China have expressed their concern over the currency moves, which drive up the value of their currencies and undermine the competitiveness of their exports. If they decide to enter the playing field, like Venezuela, which has devalued its currency by 32 percent, the world would plunge into competitive devaluations. Competitive devaluations would lead to run-away inflation or hyperinflation. Nobody will win with these types of currency wars.

James Rickards, author of “Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisis,” expects the international monetary system to destabilize and collapse. In his views, “there will be so much money-printing by so many central banks that people’s confidence in paper money will wane, and inflation will rise sharply.”4

If policymakers truly want to ward off this currency war, then it is a matter of doing what was done in 1985 with the Plaza Accord.* This time, however, we will need a different version, as it will not be about the United States and the then G-5 in 1985. It will have to be an Asian Plaza Accord under the support and auspices of the G-20. It should be about the Asian export led and mercantilist leadership agreeing among them. The chances of this happening, of advanced economies seeing the necessity of it, or these economies relinquishing its powers in any meaningful way, are not possible under current political strategies.

Currency War Means Currency Suicide

Special contribution by Patrick Barron*

What the media calls a “currency war,” whereby nations engage in competitive currency devaluations in order to increase exports, is really “currency suicide.” National governments persist in the fallacious belief that weakening one’s own currency will improve domestically produced products’ competitiveness in world markets and lead to an export driven recovery. As it intervenes to give more of its own currency in exchange for the currency of foreign buyers, a country expects that its export industries will benefit with increased sales, which will stimulate the rest of the economy. So we often read that a country is trying to “export its way to prosperity.”

Mainstream economists everywhere believe that this tactic also exports unemployment to its trading partners by showering them with cheap goods and destroying domestic production and jobs. Therefore, they call for their own countries to engage in reciprocal measures. Recently Martin Wolfe in the Financial Times of London and Paul Krugman of the New York Times both accused their countries’ trading partners of engaging in this “beggar-thy-neighbor” policy and recommended that England and the United States respectively enter this so-called “currency war” with full monetary ammunition to further weaken the pound and the dollar.

I, Patrick, am struck by the similarity of this currency-war argument in favor of monetary inflation to that of the need for reciprocal trade agreements. This argument supposes that trade barriers against foreign goods are a boon to a country’s domestic manufacturers at the expense of foreign manufacturers.

Therefore, reciprocal trade barrier reductions need to be negotiated, otherwise the country that refuses to lower them will benefit. It will increase exports to countries that do lower their trade barriers without accepting an increase in imports that could threaten domestic industries and jobs. This fallacious mercantilist theory never dies because there are always industries and workers who seek special favors from government at the expense of the rest of society. Economists call this “rent seeking.”

A Transfer of Wealth and a Subsidy to Foreigners

As I, Patrick, explained in my article “Value in Devaluation?”5 inflating one’s currency simply transfers wealth within the country from nonexport related sectors to export related sectors and gives subsidies to foreign purchasers.

It is impossible to make foreigners pay against their will for the economic recovery of another nation. On the contrary, devaluing one’s currency gives a windfall to foreigners who buy goods cheaper. Foreigners will get more of their trading partner’s money in exchange for their own currency, making previously expensive goods a real bargain, at least until prices rise.

Over time the nation which weakens its own currency will find that it has “imported inflation” rather than exported unemployment, the beggar-thy-neighbor claim of Wolfe and Krugman. At the inception of monetary debasement the export sector will be able to purchase factors of production at existing prices, so expect its members to favor cheapening the currency. Eventually the increase in currency will work its way through the economy and cause prices to rise. At that point, the export sector will be forced to raise its prices. Expect it to call for another round of monetary intervention in foreign currency markets to drive money to another new low against that of its trading partners.

Of course, if one country can intervene to lower its currency’s value, other countries can do the same. So the ECB wants to drive the euro’s value lower against the dollar, since the U.S. Federal Reserve has engaged in multiple programs of quantitative easing. The self-reliant Swiss succumbed to the monetary debasement Kool-Aid last summer when its sound currency was in great demand, driving its value higher, and making exports more expensive. Lately the head of the Australian central bank hinted that the country’s mining sector needs a cheaper Aussie dollar to boost exports. Welcome to the modern version of currency wars, AKA currency suicide.

There is one country that is speaking out against this madness: Germany. But Germany does not have control of its own currency. It gave up its beloved Deutsche Mark for the euro, supposedly a condition demanded by the French to gain their approval for German reunification after the fall of the Berlin Wall. German concerns over the consequences of inflation are well justified. Germany’s great hyperinflation in the early 1920’s destroyed the middle class and is seen as a major contributor to the rise of fascism.

As a sovereign country Germany has every right to leave the European Monetary Union (EMU) and reinstate the Deutsche Mark (DM). I, Patrick, would prefer that it go one step further and tie the new DM to its very substantial gold reserves. Should it do so, the monetary world would change very rapidly for the better. Other EMU countries would likely adopt the Deutsche Mark as legal tender, rather than reinstating their own currencies, thus increasing the DM’s appeal as a reserve currency.

As demand for the Deutsche Mark increased, demand for the dollar and the euro as reserve currencies would decrease. The U.S. Federal Reserve and the ECB would be forced to abandon their inflationist policies in order to prevent massive repatriation of the dollar and the euro, which would cause unacceptable price increases.

In other words, a sound Deutsche Mark would start a cascade of virtuous actions by all currency producers. This Golden Opportunity should not be squandered. It may be the only non-coercive means to prevent the total collapse of the world’s major currencies through competitive debasements called a currency war, but which is better and more accurately named currency suicide.

Value in Devaluation?

The euro is in trouble. That is not news. What is news is that people with deep pockets are willing to pay for economists to provide a solution. Lord Wolfson,6 the chief executive of Next, UK, has offered a £250,000 prize for the best way a country can exit the EMU. Five finalists for the prize were announced in March 2013, but none of the five finalists—Neil Record, Jens Nordvig, Jonathan Tepper, Catherine Dobbs, and Roger Bootle— advocates a return to sound money; all assume that new, national fiat currencies will float; and all assume that unproductive countries will benefit from devalued new currencies.

The theory is that a devalued currency will spur export-driven economic growth. Furthermore, they have little confidence that economic reforms—which they all, by the way, do recommend—will be achieved in the near term and see devaluation as a quicker alternative. But will this work? First a word about devaluation itself.

Devaluing against Gold

Historically, devaluation of a currency referred to its relationship to gold. Gold could not be expanded in any appreciable amounts very quickly. It had to be dug up, minted, and placed into circulation at some expense over a long period of time. Coin clipping and substituting a base metal for some percentage of the gold in coins were early means of money debasement. Later, paper currencies could be expanded as quickly and as cheaply as the mint could run paper through its presses, but even this pales in comparison to these electronic times in which money can be expanded to any amount desired at the click of a mouse.

Devaluations occurred, of course, even when governments admitted that gold was money. Notable examples are the Swiss devaluation in 1936, detailed so succinctly by Mises in Human Action, and America’s shocking 69 percent devaluation in 1934. Both of these, and others like them, were considered shameful and self-serving acts. Devaluation was tantamount to an admission of fraud. The country’s central bank had printed and circulated more units of currency than it could redeem at the currency-to-gold price it had promised its trading partners. This, of course, had disastrous effects on everyone who held contractual promises to be paid in gold.

Devaluing against Other Fiat Currencies

The devaluation advocated by many economists today is quite different in one regard. There is no commodity reserve—gold or silver, for example—against which the nation’s currency is to be devalued. Modern devaluation advocates refer to the currency’s value, or exchange ratio, in relation to all other fiat currencies. The exchange value between currencies is governed by purchasing-power parity, which is the simple comparison of the price levels of two countries as expressed in local currency. Nevertheless, the mechanism for devaluing is still the same as that which occurred under gold: inflation of the fiat-money supply.

For example, the central bank could give foreign buyers more local currency with which to buy local goods. This increased supply of local currency eventually works its way through the economy, raising all prices. Economists refer to this process as “importing inflation.” The devaluation advocates attempt to convince their countrymen that what was once a shameful act is now a positive good. For example, the Swiss are trying to lower the value of their currency in relation to all others.

What of the proposition that taking positive steps to devalue one’s own currency against all others, if it can be achieved, will actually help a country become more competitive? What have others said on this subject?

Insights from Immanuel Kant, Frederic Bastiat, and Henry Hazlitt

A policy of currency devaluation can be judged by whether or not it satisfies Immanuel Kant’s “categorical imperative,” which asks whether the action will benefit all men, at all places, and at all times. Certainly devaluation will benefit exporters, who can expect to make more sales. Their foreign customers get more local currency in exchange for their own. Exports increase. The exporter’s position is one that is best examined by considering Frederic Bastiat’s brilliant essay “That Which Is Seen, and That Which Is Not Seen” and “The Lesson” found in Henry Hazlitt’s Economics in One Lesson.

At the instance of exchanging his money for more local currency, the foreign buyer will indeed be inclined to purchase more of the goods from the country that devalued. This we can see, and most pundits consider it a good thing. The exporter’s increased sales can be measured. This is seen. But what about the importer’s lost sales? Importers can expect the opposite. The local currency will buy less, and they can expect sales to fall due to the necessity of raising prices to reflect the reduced purchasing power of their local currency. How can someone measure sales that never happened? This is Bastiat’s unseen.

Hazlitt would tell us to look at the longer-term effects of Bastiat’s insight. What is seen is that exporters get first use of the newly created money and buy replacement factors of production at current prices. The increased profits from the higher sales enrich them, because they are the early receivers of the money. But how about those who get the money much later, such as wholesalers, or not at all, such as retirees?

Over time the new money causes all prices to rise, even the exporter’s factors of production. The benefits to the exporter of the monetary intervention have slowly evaporated. The costs of his factors of production have risen. His sales start to fall back to pre-intervention levels. What can he do except lobby the government for another shot of monetary expansion to give his customers even more local currency with which to buy his products?

Monetary Expansion Creates the Boom-Bust Cycle

Even this increase in overall prices and their redistributive effects is not the entire story. The increase in the nation’s money supply will cause the boom-bust business cycle. The Wolfson Prize finalists, who see historical evidence in the beneficial effects of devaluation, have misinterpreted the boom phase. For example, Jonathan Tepper writes “in August 1998, Russia defaulted on its sovereign debt and devalued its currency. The expected catastrophe didn’t happen.” Later he writes, “Argentina was forced to default and devalue in late 2001 and early 2002. Despite dire predictions, the economy did extraordinarily well.” But these are merely the expected and temporary appearances of the boom phase caused by monetary expansion. Not only does the bankrupt nation shed itself of its debt and get to keep its ill-gotten gains; its expansionist monetary policy touches off a speculative boom. Neither Russia nor Argentina has built sustainable, capitalist economies.

The Exporter as Wealth-Transfer Agent

It should be clear that there is no net benefit to the country that drives down the purchasing power of its currency through monetary expansion. The only reason the exporter makes more sales is that the buyer of the exporter’s goods gets a lower price. This lower price was not the result of manufacturing efficiencies, but of a subsidy—a transfer of wealth—from some in the exporting country to the foreign purchaser of the goods. With each successive monetary expansion, wealth is funneled to the exporter, his employees, and others who get the money early in the expansion phase. All others are harmed. In effect, his fellow citizens who are the late receivers of the new money have subsidized the exporter’s sales. The exporter is the unseen means by which the transfer is affected. The nation as a whole is worse off; it is not more competitive.

Delaying Real Reform in a Fruitless “Race to the Bottom”

Politicians and their professional economist supporters are doing their fellow citizens an injustice by pursuing devaluation as a quick and easy means to improve national competitiveness. The source of real competitive advantage is through liberal reform of economic policies that reward industriousness in a people, to protect their property and even that of foreigners from confiscatory taxation, and encourage savings. Over time the country’s capital base, in relation to its population, will increase; an increase in capital per capita, as economists say, thus raising real prosperity through increased worker productivity. Instead of forthrightly pursuing economic reform, which one must admit will be difficult, politicians and their professional-economist supporters are fomenting a “race to the bottom,” by which each country tries to boost exports via competitive devaluations against all others. The nation’s capital base will slowly dwindle through the backdoor export subsidy made possible through monetary debasement.

The Moral Hazard of the Welfare State

There is nothing preventing any member of the EMU from becoming more competitive right now. All that is required is willingness to lower prices. As the common medium of exchange, the euro reveals uncompetitive economic structures. So why do those countries wish to become more competitive, but refrain from lowering prices? The answer is the welfare state. In an unhampered market economy, there is no structural unemployment. All who wish to work can do so, because there is never a dearth of work to be done. But the welfare state removes the cost of pricing one’s labor or one’s goods and services too high. One might say that the welfare state underpins structural rigidities in an economy, such as labor laws, licensing, and so on, by removing the cost of market interventions. Devaluation does not address this underlying problem; therefore, devaluation will not cure a country’s lack of competitiveness.

Conclusion

Devaluation means monetary expansion. The new money must enter the economy somewhere , for example, payments to exporters. The ensuing bubble is misinterpreted as a sign of the success of devaluation, but the well-known deleterious effects of a rising price level, income redistribution, and malinvestment accompany the bubble. As the prices for exporters’ factors of production rise and the benefits of devaluation fade away, there will be calls for more money expansion. If more than one country pursues this policy, there ensues a disastrous race to the bottom.

The solution is sound money. Sound money reveals bad economic policy and forces each country to live within its means. Governments will come under pressure to liberalize their economies and shed themselves of the parasitic destroyers of wealth. Devaluation retards this process.

* Our opinion expressed here is from the point of you of international trade and currency exchange as far as it affects international trade, and not from the geopolitical and economic aspects of the issue. We approach the issue of currency wars not from the theoretical, or even simulation models undertaken from behind a desk in an office, but from the point of view of practitioners engaged in international business and foreign trade, on the ground, in four different countries.

* As of December 2013

* The Plaza Accord was an agreement between the governments of France, West Germany, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom, to depreciate the U.S. dollar in relation to the Japanese yen and German Deutsche Mark by intervening in currency markets. The five governments signed the accord on September 22, 1985 at the Plaza Hotel in New York City.

* Patrick Barron is a private consultant in the banking industry. He teaches in the Graduate School of Banking at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and teaches Austrian economics at the University of Iowa, in Iowa City, where he lives with his wife of 40 years. We recommend you to visit his blog at http://patrick-barron.blogspot.com/ or contact him at [email protected].