Advanced versus Emerging Markets

Overview

Advanced economies and emerging markets find themselves in different economic and political cycles, which are causing the global recovery to ascend at two different speeds. In 2011, the IMF estimated the global economy was growing at 4.4 percent, while advanced economies were growing at 2.4 percent and emerging markets at 6.5 percent. The global economic growth trend is changing significantly. Emerging markets were responsible for roughly 70 percent of the total growth of 2012, while most advanced economies are still with slow growth challenges, high unemployment, and very uncertain financial markets.

Furthermore, the average fiscal deficit for advanced economies is about seven percent of its GDP, almost two percent more than those of emerging markets, and it is likely this trend will continue for the next few years due to the high risk of fiscal sustainability. In our opinion, advanced economies should strive to balance their fiscal consolidation objectives and strengthen their economic growth.

Conversely, some emerging markets are reaching the point where their economies are beginning to overheat, which generates inflationary challenges and makes it harder to control capital flows. Such inflationary pressure in these markets is a sensitive issue. As food and basic product prices, which are included in the consumer price index (CPI) of many of these nations, such as India, Russia, and China, increase, even more inflationary pressures are created. Notwithstanding, China has continued to register robust economic performance, creating many job opportunities, improving the standard of leaving of its people, and acting as an important generator of growth in the global economy.

As for advanced economies, the challenges these countries face, in particular the United States and the EU are enormous. In early November 2013, the figures on growth, according to the U.S. federal government, continued to show signs of underlying economic weakness as EU’s European Central Bank (ECB) unexpectedly cut interest rates to a record low, reflecting the threat of deflation.

Advanced Economies Prospects

According to a New York Times article1 by Jack Ewing, the economy in the United States would experience a 2.8 percent annualized growth for the third quarter, which turned out to be too optimistic, despite the fact that it was the fastest quarterly increase in output, well above the two percent economists expected. Nearly a full point of that jump was caused by a buildup in inventory, which can sap expansion. In reality, the annual rate of growth in consumer spending slowed sharply to 1.5 percent; the weakest quarterly increase in more than two years, while spending by the federal government fell 1.7 percent.

Olivier Blanchard, chief economist at the IMF, argued in October 2013 that advanced economies were strengthening, while emerging market economies were weakening.2 Blanchard maintained that while fiscal risks in the United States, as worrisome as they are, should not lead investors to lose sight of the bigger picture. As the world economy has entered yet another transition, advanced economies are slowly strengthening. Simultaneously he contends, emerging market economies have slowed down, more so than the IMF had in July 2013.*

According to Blanchard, advanced economies’ growth should be around 1.2 percent in 2013, and two percent in 2014, while growth in emerging markets should be around 3.3 percent in 2013, and 3.1 percent in 2014, representing a slightly positive growth for advanced economies and slightly negative growth for emerging markets.

While the United States and the EU share many problems, it is clear that the situation on much of the continent is worse. Many economies in the EU are now stabilizing after six quarters of renewed recession, and unemployment across the 17 nations that share the euro currency stands at roughly 12 percent. In especially hard-hit countries like Greece and Spain, the unemployment rate is more than twice that number. As of September 2013, the latest data on unemployment in the U.S. stood at 7.2 percent. Amid the discouraging economic trends in the U.S., the consistently overly optimistic European Commission cut its growth forecast for 2014 to 1.1 percent from 1.2 percent.

Clearly, more than any other time in history, the United States and the EU’s central banks are working together as much as possible, trying to prevent further deflation of their economies. The growth prospects in the United States were further compromised by a sudden drop in the eurozone inflation to an annual rate of 0.7 percent in October 2013, well below the ECB’s official target of about two percent. The decline raised the threat of deflation, a sustained fall in prices that could destroy the confidence of consumers and the profits of companies, along with the jobs they provide.

While austerity rhetoric has taken root in both the United States and many European capitals, crimping fiscal policy, the course charted by central bankers in these two major advanced economies, in terms of monetary policy are beginning to go in different directions. Unlike the ECB, the United States has moved aggressively to stimulate the economy, not only cutting short-term interest rates to near zero, but embarking on three rounds of asset purchases aimed at lowering borrowing rates and augmenting the growth rate.

Looking ahead, the picture for growth remains cloudy for most advanced economies, particularly for the United States and the EU. We believe there are several economic and fiscal forces affecting the world today. The high indebtedness of advanced economies as a whole imposes major challenges for sustainable growth. In addition, emerging markets are still dependent on their exports to those nations, although these economies have begun diversifying their export market trading among each other with more frequency. The following is a brief overview of major global economic prospects for the main advanced economies and emerging markets, and how they are intertwined and impact one another.

The United States

The U.S. economy, despite being the largest economy in the world, has not recovered fully from the 2008 financial crisis and ensuing recession. The federal system of government, designed to reserve significant powers to the state and local levels, has been strained by the national government’s rapid expansion. Spending at the national level rose to over 25 percent of GDP in 2010, and gross public debt surpassed 100 percent of GDP in 2011. Obamacare, a 2010 health care bill, greatly expanded the central government’s regulatory role, and the Dodd—Frank financial overhaul bill roiled credit markets. In the same year, the election of a Republican Party majority in the House of Representatives helped slow government spending down, but it divided the government, leaving economic policies in flux, which continued to endure well past the reelection of President Obama in 2012.

Economic freedom also is plummeting in the United States. According to the Heritage’s 2013 Index of Economic freedom,*† the U.S has registered a loss of economic freedom for the fifth consecutive year, recording in 2013 its lowest Index score since 2000. Furthermore, our government has become increasingly more bloated, with trends toward cronyism that erodes the rule of law, thus stifling dynamic entrepreneurial growth. More than three years after the end of recession in June 2009, the United States continued to suffer from policy choices that have led to the slowest recovery in 70 years. Overall, businesses remain in a holding pattern, except for some sectors, such as the military and biotech. Unemployment is close to 7.5 percent. Prospects for greater fiscal freedom are uncertain due to the scheduled expiration of previous cuts in income and payroll taxes, and the imposition of new taxes associated with the 2010 health care law.

As of fall 2013, Blanchard* contended that the private demand in the United States continued to be strong and that economic recovery should strengthen, assuming no fiscal accidents. We can’t be sure of what he meant, but in our opinion, it seems logical that quantitative easing in the United States would need to continue for some time. Blanchard believes that, while the immediate concern for the United States is with the government shutdown that happened in the fall of 2013, and making sure it doesn’t recur, the debt ceiling issue and, the sequester policies implemented should lead to fiscal consolidation into 2014, which is both too large and too arbitrary.

Blanchard also argues that failure to lift the U.S. debt ceiling would, however, be a game changer. If prolonged it would lead to extreme fiscal consolidation, and surely derail the U.S. recovery. He continues, “The effects of any failure to repay the debt would be felt right away, leading to potentially major disruptions in financial markets, both in the United States and abroad. We [the IMF] see this as a tail risk, with low probability, but, were it to happen, it would have major consequences.”† He recommended U.S. policymakers “to make plans for exit from both quantitative easing and zero policy rates—although not time to implement them yet.”‡

At the time of this writing, in fall 2013, the debt ceiling discussion continues with the fiscal deal passed by Congress. The good news is that the government was able to reopen and was able to attain the nearly $16.4 trillion limit on borrowing. The bad news is that there is no actual debt ceiling right now, as the deal just temporarily suspended enforcement of it. For those intellectuals and economists who advocate the abolition of a debt ceiling all together, the current state of affairs is actually great news. That is, the sky is the limit when comes to U.S. government spending until February 7, 2014.

The fact that there is no dollar amount set for how much debt the government can accumulate through February 2014 is now tired-strategy, as it was first deployed earlier this year during previous fiscal battles in Congress, much to the dismay of many anti-government waste groups.

Is it responsible governance, for an advanced economy such as the United States, the largest economy in the world, to suspend a debt ceiling without a dollar amount? After all, common sense tells us that a real dollar figure in any budget, for a responsible individual or corporation, is a constant reminder of where we are in our personal or corporate finances. A dollar figure in a government’s budget portrays how much it can spend, and the overall health of the country’s finances.

It seems that a dollar figure in the U.S. federal budget may not be a good idea, especially when the country has credit agencies, such as Moody, Fitch, and Standards and Poor’s (S&P) (although there may never be another downgrade of the U.S. economy by these agencies since the U.S. government sued S&P for its downgrade), watching the United States and suggesting to taxpayers, Congress, and foreign investors, that the United States may be broke.

In our research for this book, we spoke with many business executives from multinational companies, academic researchers, and professionals from around the world. Most of the professionals and executives we spoke to wondered aloud if the fiscal strategies now in place are designed to hide the true state of U.S. debt from its taxpayers, large foreign investors, and creditors on which the country depend. So, if we were to assume that there is some veracity in the IMF assertions, such as the above, it must be taken with a grain of salt. After all, we should not expect the IMF, so dependent on U.S political support and funds, to be wholly unbiased.

Such strategies and polices undermine any informed investor, those capable of seeing through smokescreens. Any foreign investor and nation buying U.S. treasury bills will recognize a bad deal when they see it. Once these investors realize these Treasury bills are the equivalent of junk, regardless of the official rating, the buying will dry up and disastrous consequences will ensue in the financial markets and the U.S. economy as a whole.

As a disclaimer, the authors of this book do not claim to be economists. The proposition of this book to be written by non-economists was by design. We are researchers and observers of what the data and the global trading dynamics tell us, especially between advanced economies and emerging markets. But it doesn’t help to have a different opinion about the U.S economy, a less sanguine view. When the conservative Heritage Foundation3 criticizes Washington’s federal budget handling as a “smokescreen,” alleging that the suspension of the debt ceiling is becoming increasingly less transparent to the American people, and that the U.S. government spending exceeds federal revenues by more than one trillion dollars, it is difficult not to have a gloomy outlook.

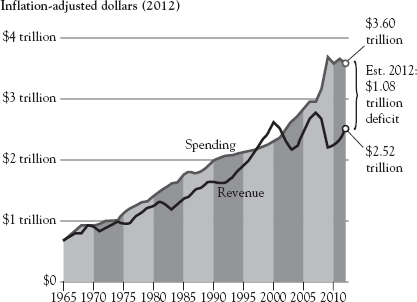

As shown in Figure 3.1, since 1965, spending has been rising steadily. While federal revenues are recovering from the recent recession, spending is growing sharply, resulting in four consecutive years of deficits exceeding one trillion. Nonetheless, the U.S. Congress is still ignoring the proverbial elephant in the room, no matter how big and wide it gets as days go by, only so they can avoid debate on the specific dollar amount increase on the debt limit, thus making their political vote much easier to cast. It is much easier to vote on when we’ll deal with a trillion dollar problem than to actually deal with the problem.

It took the U.S. government debt 200 years to reach $1 trillion in 1980, but just 20 years to reach $5 trillion in 2000, and only 13 years to reach about $17 trillion this year. The trend leaves no ambiguity. Despite the talks in Washington, logic indicates the deficit will continue to rise, with more power than in the past 10 years due to the increased interest rates, and the undeniable fact that more Americans are retiring. The debt, as it stands, will continue to increase. By how much will it increase? One, two, or perhaps $3 trillion if the United States engages in other wars in the interim.

Figure 3.1 Federal spending exceeds federal revenue by more than $1 Trillion

Source: U.S. Office of Management and Budget

Huge swaths of the global financial system, including in advanced and in emerging economies, is structured around the understanding that United States. Treasuries are the safest asset in the world. What would happen if that assumption were ever called into question? We believe global financial havoc would ensue, which is precisely why Moody’s thinks that a default on U.S. debt is unlikely, even if we smash into the debt ceiling.

Furthermore, if the U.S. Treasury wants to conserve enough cash to keep servicing the debt, then it will have to miss or delay a several other important payments in the near future. If the U.S. Treasury pays the required six billion dollar interest payment by the end of October 2013, and another $29 billion dollars in interest payment by November 15, 2013, the United States may have no choice but to delay social security checks, Medicare payments or military pay, unless it borrows more from China, or simply prints more money.

Restoring the United States to a place among the world’s free economies will require significant policy reforms, particularly in reducing the size of government, overhauling the tax system, transforming costly entitlement programs, and streamlining regulations. Paraphrasing Mark Twain, history may not repeat itself and only rhymes. But we do believe wholeheartedly in Ayn Rand’s assertion* that every one of us builds our own world in our own image. We have the power to choose, but no power to escape the necessity of choice.

Japan

After 55 years of Liberal Democratic Party rule, the Democratic Party of Japan captured both houses of parliament in 2009 and installed Yukio Hatoyama as prime minister. Hatoyama resigned abruptly in June 2010 and was succeeded by Finance Minister Naoto Kan, who was replaced in September 2011 by Yoshihiko Noda. The March 2011 earthquake and tsunami further strained the beleaguered economy, which has been struggling for nearly two decades with slow growth and stagnation. Prime Minister Noda strived to include Japan in the TPP to stimulate the economy but faces strong resistance at home. Successive prime ministers have been unable or unwilling to implement necessary fiscal reforms. As a result of this long and persistent economic crisis, Japan’s economy is still about the same size as it was in 1992. In essence, Japan has lost more than two decades of growth.* The 2008 global financial crisis and the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake only aggravated the situation, imposing two severe and consecutive shocks to the Japanese economy. The earthquake alone, the worst disaster in Japan’s post-war history, killed nearly 20,000 people and caused enormous physical damage.

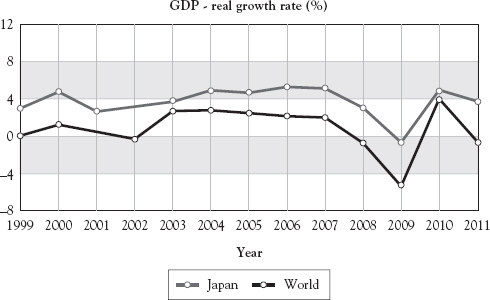

According to the OECD,5 prior to the global economic and financial crisis (as shown in Figure 3.2), Japan’s initial strong recovery from the earthquake and tsunami stalled in mid-2012, leaving output 2.5 percent below the peak recorded in 2008. The earthquake and tsunami only compounded Japan’s distressed economy. The country has experienced three recessions in less than five years.

Consequently, the major challenge for Japan’s economy is to find a way to achieve sustained growth and fiscal sustainability following these two major disasters; the country suffered a 0.7 percent loss in real GDP in 2008 followed by a severe 5.2 percent loss in 2009. Exports from Japan also shrunk from $746.5 billion dollars to $545.3 billion dollars from 2008 to 2009, a 27 percent reduction. Japan certainly is as handcuffed by its own rigidities as any other country. What is worrisome is that while some export-oriented industries have remained competitive, the Japanese domestic economy appears to be held hostage by bureaucracy, tradition, and overregulation.

Figure 3.2 Japan has faced two major economic shocks since 2008

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database

Figure 3.3 Japan’s economy has fallen below global growth

Other countries would do well to take note of this conundrum as the same concerns Japanese businesses face, certainly would affect businesses globally. It is the authors’ suggestion that both advanced and emerging economies should take on these challenges, even the stalwart ones of old Europe: Spain, Italy and France. These all tend to be myopic toward a focus on domestic consumption instead of savings and investments. Often, insufficient attention is given to the unattractive, frequently politically toxic load of smaller policy challenges that can be critical to restarting a faltering economy. For the purpose of reference, in 2011, global real GDP growth was up a 3.9 percent,6 as depicted in Figure 3.3, while Japan had fallen below global growth at –0.7 percent.

Furthermore, Japan’s public debt ratio, as shown in Figure 3.4, has risen steadily for two decades, exceeding 200 percent of GDP. The country must, therefore, promote strong and protracted consolidation to mitigate fiscal sustainability. This is by far Japan’s major policy challenge; as such policy will decelerate nominal GDP growth, making fiscal adjustments still more difficult. Hence, ending deflation and boosting Japan’s growth potential is imperative in addressing the fiscal predicament in which it finds itself. Consequently, Japan’s new government’s determination to revitalize the economy through a three-leg strategy combining bold monetary policy, flexible fiscal policy, and a growth strategy is not only necessary, but admirable.

Figure 3.4 Japan’s gross public debt as percentage of the GDP

Source: OECD Economic Outlook, No 92, and revised OECD estimates and projections for Japan for 2012–14

One immediate way the country is responding to the crisis, according to Kathy Matsui,7 chief Japan equity strategist for Global Investment Research with Goldman Sachs, is by Japanese companies buying companies overseas, more so than we have seen to date. But whether the recovery in Japan continues, it can only be sustained by Abenomics* policies in meeting two major challenges. The first, reflected in the debate about an increase in the consumption tax, is the right pace of fiscal consolidation as it should not be either too slow and compromise credibility, or too fast and stymie growth. The second is a credible set of structural reforms to transform a cyclical recovery into sustained growth.

Hopefully the Tokyo stock market will continue to rally. The Japanese yen and its stock market have benefited from Abenomics expansionary policies. Having lost as much as 18 percent by mid-May 2013, the yen currently is down around 12 percent on the year, which is a windfall for a currency-sensitive exporter, such as Japan. In the fall of 2012 the economy surged 65 percent, while in the second quarter of 2013 the economy expanded by 3.8 percent, faster than any other advanced economy. Prices are edging upward, which is a good thing for Japan’s fight on deflation. Yet, the disposition in Tokyo among businessmen and economists remains perilously balanced between enthusiasm for the monetary and fiscal stimulus unleashed by Abenomics, and concern that promised structural reforms might not be implemented.

The European Union

As of fall 2013, the EU has shown some signs of recovery. This is not due, however, to major policy changes, as in Japan, but partly to a change in mood, which could be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Southern periphery countries such as Spain, Greece, Italy, Portugal, still struggle as definite progress on competitiveness and exports are not yet strong enough to offset depressed internal demand. Hence, there is still much uncertainty in the EU, the largest economy in the world as a bloc. Bank balance sheets remain an issue, but should be reduced according to the promised asset quality review recommended by European Banking Authority (EBA). Such close scrutiny of EU’s banks may turn up unexpected shortfalls though. Like Japan, larger structural reforms are needed urgently to increase the anemic potential growth rates of the EU.

The Uncertain Fate of the Olive Growing Countries and the Euro

The debt crisis continues to overwhelm Europe, and the prospects for countries most entrenched in debt, including Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain, and Ireland, are dismal. Worse, regardless of whether these countries voluntarily leave or are coerced to leave, it is conceivable that Germany may opt to go solo. The not-so-popular George Soros argues that the euro crisis is far worse than earlier estimations, suggesting that it could eventually end up dissolving the EU.

In a Berlin speech in late April 2012, Soros indicated that the EU crisis casts a shadow on the global economy, a consequence of its own political evolution. He argues that the Maastricht Treaty,4† which led to the creation of the euro, and created what was commonly referred to as the pillar structure of the European Union, was fundamentally flawed, as it established a monetary union without a political one. In essence, the euro was launched without any real democratic consultation or approval, intended by world leaders as political glue in the march toward pan-European sovereignty.

Whereas global analysts and the mainstream media seem to overlook much of this threat to the world’s second largest reserve currency, the more immediate concern is the possibility that Germany will abdicate from the EU, causing the euro to plummet, which could subsequently trigger a major international monetary crisis. The EU may survive with a few less olive growers such as Portugal and Greece, but certainly not without the solid backing of Germany.

While the world watches with hopeful expectations for the first time in history, the synchronicity of the central banks of Europe, UK, China, India, Japan, and the United States printing fresh money and increasing the base supplies of their respective countries, we tend to forget important historic facts about Germany and the eurozone. Namely, Germany was never sanguine about the euro from the onset. In fact, most Europeans were not. We view it more as a quid pro quo case, whereby Germans accepted the euro in exchange for France’s support of Germany’s post-Cold War reunification. Trading the Deutsche mark for the euro, in and of itself, did not equate logically.

EU’s dire situation provides Germany with an opportunity to augment its political influence in the region, and a return on its investment of the euro, by way of financial rescue packages to olive growers. However, if such efforts fail, as is likely the case, Germany will have no compelling reason to remain with the EU, since Europeans are already becoming resentful of Germany and the EU. History has shown us time and again that austerity breed’s political disgust, particularly when imposed by outside powers. A pro-German government in Holland has already fallen in local elections, and President Sarkozy lost ground in his reelection campaign, eventually losing the elections, precisely due to his perceived support of German policy. Then there are the German people who resist the idea of seeing their hard earned money squandered on people who refuse to tighten their belts.

The central bank’s printing of money and Germany’s financial packages are not ameliorating the situation. On the contrary, the olive growers are not alone. Many other countries are already in recession, including Slovenia, Italy, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Denmark, Netherlands, Belgium, and the UK. Whether the euro endures, Europe, especially the olive growing countries, is facing a long period of economic stagnation. We witnessed Latin American countries suffer a similar fate in the early 80s, and Japan, which has been in stagnation for almost a quarter century. While they have survived, the eurozone situation is graver, as the EU is not a single country but rather a union of many; the lingering deflationary debt trap threatens to destroy a still nascent political union.

We believe that only when a friendlier monetary policy and a milder fiscal austerity is proposed will the euro remain strong. This will weaken the eurozone’s exports’ competitiveness, and drag the recession to even lower levels, which in turn will force more eurozone countries to restructure their debts and may cause some to ultimately exit the euro.

EU’s Economic Prospects

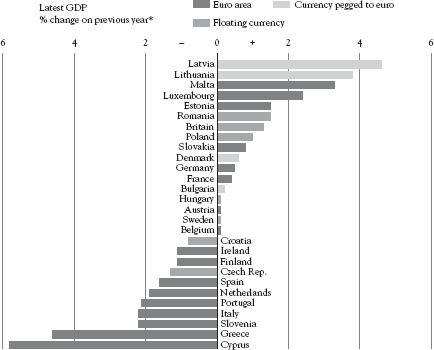

The Economist magazine expects GDP will stagnate across the 28 largest economies within the EU in 2013, after falling by 0.5 percent in 2012, and expand by 1.4 percent in 2014. This is according to forecasts from the European Commission in early November 2013, as this chapter is written. Across the 17 largest countries in the EU, however, a weak recovery has begun, following a double-dip recession lasting 18 months. For 2013 GDP in the EU, as a whole, will fall by 0.4 percent, after falling by 0.6 percent in 2012. In 2014 GDP is expected to rise by 1.1 percent. Figure 3.5 provides information on GDP growth by country for those in the EU, those pegged to the euro, and those countries floating their currency as of the first quarter of 2013.

As was the case in 2013, growth in 2014 will be strongest (4.1 percent) in Latvia, which is poised to join the euro area in January. Indeed the three Baltic countries, including Lithuania outside the eurozone and Estonia already in it, will be the three fastest-growing economies in the EU. But the main impetus behind the euro area’s recovery will be a combination of German growth of 1.7 percent coupled with a more modest return to growth in Italy and Spain, the region’s third and fourth biggest economies. Outside the eurozone, Sweden and Britain are expected to do well in 2014, with growth of 2.8 percent and 2.2 percent respectively.

Figure 3.5 GDP growth across the EU countries

Source: Eurostat

The worse performers for 2014 are two countries also in the eurozone, who will experience a decrease on GDP: Cyprus and Slovenia. Cyprus’s distresses will continue, with a further contraction, of 3.9 percent, while Slovenia’s GDP also will slide again, by one percent. Nonetheless, such prospects should be considered positive; GDP is expected to fall in eight countries in the eurozone and 10 in the EU. Lastly, the minor recovery in 2014 should not bring much joy for the jobless, as unemployment in the eurozone still is expected to stay at 12.2 percent in 2014. This statistic is much higher with olive grower countries; Spain is registering 32 percent youth unemployment as of fall 2014.

We believe the euro area has the potential to take advantage of the global opportunities, especially emerging markets. The euro area is more open to trade than many other advanced economies. The EU’s exports and imports of goods and services account for around one fifth of GDP, more than in the United States or Japan. The EU has been open to the idea of emerging markets. Its trade relations with emerging markets such as Asia, Turkey and Russia, for instance, as well as with central and eastern European countries, have strengthened noticeably over the past decade. Taken together, the share of emerging markets in the euro area trade has grown from about 33 percent, when the euro was introduced in 1999, to more than 40 percent as of 2013.8

One aspect less well known about the eurozone is that it is financially very flexible and open. The international balance sheet of the eurozone, its assets and liabilities vis-à-vis nonresidents account, is over 120 percent and 130 percent of euro area GDP, respectively. This is more than in many other advanced economies such as the United States, where the corresponding figures are 90 percent and 110 percent of GDP. In addition, according to Trading Economics,9 the EU is becoming increasingly open. Since the euro was created, the size of the eurozone area’s external assets and liabilities has grown by about 40 percent. Hence, if we were to focus on emerging markets alone, one of the most interesting developments in recent years is the fact that the eurozone has become an attractive destination for FDI from the largest of these economies. For instance, during 1999–2005, the amount of FDI from Brazil, Russia, India, and China in the eurozone tripled, to about €12 billion euros (US$16.2 billion).

Emerging Markets

The long-term fundamentals for emerging market growth, we believe, are directly linked to the potential for emerging market companies to tap into the favorable long-term economic growth prospects for all the emerging economies. As pointed out in earlier chapters, those growth prospects are based on two main factors: positive demographic trends (with some exceptions) and balance sheets that are not reliant on and burdened by debt, as seen across advanced economies. Combined, these are potent and sustainable benefits for emerging markets.

The rising population numbers that many emerging nations are experiencing help to ensure that aggregate demand will grow faster while the strong and underleveraged balance sheets—of both consumers and sovereigns—help to assure investors the pace of investments and consumption can be kept in balance. This is in contrast to the deleveraging process— both at the government and consumer level—that will take years to run its course in many developed markets. Such deleveraging will continue to exert strong deflationary pressures on these developed economies. While there is a great deal of uncertainty as to how developed-market central banks will counter these pressures, any expansion of global liquidity should favor assets with better growth prospects, such as the ones found in emerging market economies.

We believe, however, that emerging markets need to exercise some caution (driven by the prospects for liquidity withdrawal), should the U.S Federal reserve and the ECB, as well as other advanced economies’ central banks, begin to shutter their quantitative easing programs. Relatedly, we see signs that currency and interest rates in many emerging markets need to adjust to more sustainable equilibriums. For instance, in the BRICS bloc, currencies need to depreciate and real interest rates need to rise. While this may be tough to enact, it is necessitated by the deterioration of the aggregate current account balance of the emerging market universe since 2007, which has been caused by the weak demand from advanced economies, weakening commodity prices, and the stimulating domestic demand policies that have prevailed in many emerging markets since the global financial crisis.

A correction already has started as many emerging market currencies have been depreciating against the U.S. dollar and the euro for nearly a year. These downward trends have been distinctly unfavorable since the rebound at the end of the crisis. We also are starting to see some upward ticks in interest rates in certain countries. As part of this adjustment, there is a possibility that we will see lower economic growth, which could be negative for earnings-growth expectations. The market has already started to discount this notion, as seen through the lower valuations of emerging versus advanced economies.

The causes for such trends vary in opinion. There is a belief that emerging markets may be in a cyclical slowdown. Another belief is that emerging markets are now experiencing a decrease in growth potential. We believe, based on our own research that both are true. Extraordinarily favorable world conditions, be it strong commodity prices or global financial conditions, led to higher potential growth in the 2000s, with, in a number of countries, a cyclical component on top. As commodity prices began to stabilize and financial conditions tightened, potential growth is lowered and, in some cases, compounded by a sharp cyclical adjustment. Faced with these conditions, governments in emerging markets are now faced with two challenges: adjust to lower potential growth, and, where needed, deal with the cyclical adjustment.

Considering a potential slow down on these economies, at least when compared to the 2000 rates, structural reforms will not only be necessary, but urgent. Such structural reforms may include rebalancing toward consumption in China, or removing barriers to investment in India or Brazil. Regarding cyclical adjustments, the typical standard advice from macroeconomics applies, such as the consolidation of debt in countries with large fiscal deficits. Countries with inflation running persistently above government targets, such as in Vietnam and Indonesia, a tighter and, even more importantly, more credible monetary policy framework must be implemented.

When assessing the prospects for advanced economies, the architecture of the financial system is still evolving, and its future shape and soundness are still unclear. Unemployment remains too high, which will continue to be a major challenge for several years to come. As for emerging markets, and the implications of its rise in the world economy, the impact is multifaceted, and is already being felt around the globe. It encompasses two areas of immediate concern for central bankers in those countries and around the world, namely global inflation and global capital flows.

The Impact of Emerging Markets Rise on the Global Economy

The integration into the global economy of a massive pool of low-cost, skilled workers from emerging markets has tended to exert downward pressure on import prices of manufactured goods and wages in advanced economies.10 Emerging markets have significantly contributed to the increase of the labor force and the reduction of labor costs around the world. The available labor force in the global economy has actually doubled from 1.5 to 3 billion, mainly as a reflection of the opening up of China, India and Russia’s economies. The price of a wide range of manufactured goods has declined over the years. Furthermore, through numerous channels, this process of wage restrains and reduced inflationary pressure in the manufacturing sector also has affected wage dynamics and distribution in the services sector, mainly due to outsourcing. Consequently, these effects have contributed to the dampening of inflationary pressures.

Conversely, there are opposing dynamics to be considered between advanced economies and emerging markets. Some resources, such as energy and food, have become relatively scarce over time due to the increased demand from emerging economies, such as China and India. We believe this may have been a source of increased inflationary pressure over the past few years, although we acknowledge that it is difficult to make an exact assessment of this contribution, since commodity prices also are affected by supply conditions and geopolitical factors. Nonetheless, according to Pain, Koske, and Sollie’s study,12 the rapid growth in emerging countries and their increasing share in world trade and GDP may have contributed to an increase in oil prices by as much as 40 percent, and real metal prices by as much as 10 percent in the first five years of the new millennium.

All in all, it is difficult to measure accurately the total impact of emerging markets on inflation. For instance, the IMF has estimated that globalization, through its direct effects on non-oil import prices, has reduced inflation on average by 0.25 percent per year in advanced economies.13 The overall impact, however, is more difficult to estimate and extricate from other factors that could reduce inflation. For example, the increases in productivity growth and the stronger credibility of monetary policy are two impending factors.

A New Form of Capitalism

Recently, Dr. Goncalves returned from China, and during his return flight, he came to the realization that although he teaches on the subject of China in his international business program at Nichols College, he had missed the point when it came to that country’s profile. He kept thinking about how Taipei, a democracy in Taiwan, with all of its tall gray buildings seemed more like a communist country than China. In contrast, Hong Kong’s Time Square, the World Trade Centre, Causeway Bay, and its SOHO seemed more like Manhattan on steroids. Despite the plethora of books and articles he’s read on the subject, he came to realize that Chinese communism today isn’t anything like his antiquated vision of it, which was formed by living in the United States and shaped by the Soviet Union (now Russia).

The communism he witnessed in Hong Kong and Macau, although we must note these two countries are China’s Special Administration Regions (SARs), are true examples of capitalism at its core. In contrast to the West and most advanced economies today, unemployment rates in Hong Kong and Macau are only four and two percent respectively. Hong Kong hosts the most skyscrapers in the world, with New York City a distant second, with only half the amount. Hong Kong also holds the most Rolls Royce’s in the world. Macau’s per capita income is $68 thousand, in contrast to $48 thousand in the United States.

What impacted him the most during his 21 days there was the optimism of it’s people. This is in contrast to the cynicism heard constantly in the West, where people seem to have lost their excitement about the future. There, young and old, people yearn and strive for more than what they have. He agrees with Goldman Sachs’ Jim O’Neill, who coined the “BRIC countries” back in 2000, in his assertion that “China is the greatest story of our generation.”14 China’s general macroeconomics is very promising. It scores well for its stable inflation, external financial position, government debt, investment levels, and openness to foreign trade. At the micro level it falls just below average on corruption and use of technology. But, the latter is changing rapidly.

There simply is no overstating China’s importance to us all, particularly the West, notwithstanding the 1.3 billion Chinese. Like it or not, we must realize that the entire planet, all 6.5 billion, is and must be invested in China’s success. Doubts? In 1995, China’s economy was worth roughly $500 billion. In just sixteen years it has grown more than tenfold. By 2001, its GDP was $1.5 trillion, at the time it was smaller than the United Kingdom and France. Today, China is the second largest economy in the world.

Undeniably, it will be a hard road for China to maintain its consistent 9–10 percent annual growth moving forward. Their growth rates will most certainly decelerate. The question is by how much and how smoothly. In March 2014, the government announced a 7.5 percent growth target for its 35-year plan. This is best for its economy and people so that policy makers can better focus on the quality of the growth, instead of sheer quantity. After all, no country can sustain growth by building ghost cities as China has been doing. The good news is that China does not have to maintain the 10 percent GDP growth pace in order to continue to grow, and actually surpass the United States to become the largest economy in the world. For now, China is still only about one third of the U.S. economy (in comparable dollar terms).

It appears that China’s Communist Party, with 80 million members, is not just the world’s largest political party but also its biggest chamber of commerce. That can be worrisome, as China’s influence and impact on all advanced and emerging markets around the world looms large. The eurozone crises have many of us in the United States concerned. As it deteriorates, it will definitely impact Wall Street and the U.S. economy. However, anything that happens in China is far more important and impactful to the fate of the world economy than the eurozone crises.

China’s Challenges

As Brazil, Russia, India, and China, the BRIC countries, advance full-steam ahead, Jim O’Neil’s decade-old prediction for this group of only four countries remains prescient. BRIC is growing an economy that will surpass the combined size of the great G-7 economies by 2035.* Very little is said, however, about China’s shattering stories of the hordes of small business owners committing suicide, leaving China, or flat out emigrating to the West. It makes me wonder how much vested interest Goldman Sachs has in such predictions.

Don’t get us wrong. We are avid proponents of the rise and formidable influence the BRIC countries are having on the global economy. In my (Dr. Goncalves) Advanced Economies and Emerging Market classes, my students are exposed to detailed characteristics of the engine propelling the BRICs, its impact on the G-7, and how to position themselves professionally to capitalize on it. But, we cannot ignore the public outcry of Chinese entrepreneurs facing the deterioration of business conditions in that country.

The somewhat positive step taken by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) in December 2012, to alleviate China’s alleged liquidity crisis, should cause us to reassess the sustainability of its economy at current rates. China is far from a liquidity crisis, however, possessing an M2* that has surpassed the United States, reaching nearly US$11.55 trillion. This was due, in part, by reducing the reserve requirement ratio†, (RRR), to 21 percent from its record high of 21.5 percent.

It is not clear to us whether China is on a sustainable economic path, at least until it slows down its equity investments and begins to pay more attention to and empower its middle class. The Chinese people won’t be willing to spend if they don’t have a decent health or retirement system, which impels them to save, on average, 30 percent of their income. China’s obsession with extreme growth, sustained now for over a decade, has become the huge white elephant for global markets. Unless the Chinese government begins to deal diligently with this issue, it may not be able to prevent an epic hard landing of its economy.

Much like Western economies, China blames the tightening of monetary policy as the feeder of its ever-growing white elephant. Again, much like the West, it looks more like a systemic issue, since its main markets, the United States and Europe, are both battling a probable imminent double recession, which is squeezing their buying power. In addition, ahead of the West, inflation is rising. Wage inflation especially is causing the hungry elephant to erode China’s main competitive advantage in the manufacturing industry. The tightening of monetary policy is anathema to this, but the transformative systemic change in the Chinese economy isn’t. Just look at the Purchasing Manager Index* (PMI), which dropped to 49 in December, much lower than market expectations, to realize that the manufacturing sector is bleeding. In early 2013 the PMI climbed to 53, but manufacturing goods in China have been declining. As depicted in Figure 3.6, in October 2013, China’s PMI fell to 52.6, and even further, to 50.2 in February 2014.

Such declines in PMI produce a ripple effect of stocks piling up, thereby driving the cost of doing business higher. So much so that it has become cheaper for China to transfer its manufacturing to the United States, primarily to South Carolina. Certainly, labor costs, even in the south of the United States, are higher than in China. But the cost of energy is a lot cheaper, as is the cost of real estate, infrastructure, and shipping across the Pacific.

What makes China’s white elephant so pale is that small and medium businesses (SMBs), the driving force of China’s manufacturing, do not have easy access to credit. China’s four major banks, Bank of China, the China Construction Bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and the Agricultural Bank of China, control more than 70 percent of China’s banking market. These are state-owned banks which favor state-owned companies, and, rarely, some fortunate private corporations. This resource misallocation is feeding the pallid pachyderm at the expense of SMBs, left with their only option of costly business financing.

We do not profess to be economists, but looking at the sheer size of China’s white elephant, it is clear to us that monetary policy alone cannot fix the systemic insufficiencies of China’s economy. As long as the economy remains vastly dependent on the United States and European consumerism, countries currently dealing with their own herd of white elephants, and unable to consume as before, China’s exports will remain massively strained. Consequently, the country is being burdened with a severe excess capacity problem, pushing down the marginal returns of investment and GDP, while fostering an uptick of inflation, unemployment, and possibly more bubbles.

As the United States and Europe deal with their own economic crisis, they are being forced to place their deficit-fueled consumption economies on a stringent diet. To deal with their own white elephant they will have to shop and consume less, to give room for increasing saving rates, chronically low at the moment, and higher productivity. Such an unavoidable consumer diet could be disastrous for China, as data from the Economist Intelligence Unit and the U.S. Department of Commerce’s (DOC) Bureau of Economic Analysis suggests that China will remain dependent on an export-led economy until at least late 2030. If true, China must find new markets and reduce its dependence on the West’s economies.

Could the BRIC countries be the ace under China’s sleeves? After all, as O’Neil predicted, in the next two decades, these four countries alone will account for half of the population of the entire world (i.e., huge middle-class), and their economies will be larger than the G-7 countries combined. Europe today has 35 cities with a population over one million, but by 2030, India alone will have 68 cities with over one million and China will have over one billion consumers living in it’s cities. This staggering fact alone could mark the slow death of China’s white elephant, by letting go of its dependence on the West, and the return of a progressive flame-throwing dragon, ready to sizzle its middle-class economy and the BRIC’s with sales aplenty of manufactured goods.

The question remains, which will have more weight: the shortsighted state-capitalist elephant or the farsighted free-market driven dragon?

Brazil: An Economy of Extremes

Dr. Goncalves recently returned from Brazil, and while observing the hustle and bustle of Rio’s international airport, busier than ever, it dawned on him that Brazil has much to be proud of. He is Brazilian, and therefore, admits to being a tad biased, but the fact remains that a decade of accelerated growth and progressive social policies have brought the country prosperity that is ever more widely shared. The unemployment rate as of September 2013 was 5.4 percent, up from 5.3 percent in August of 2013.* Credit is flourishing, however, particularly to the swelling number of people who have moved out of poverty status and into the ranks of the middle class. Income inequality, though still high, has fallen sharply.

For most Brazilians life has never been as hopeful, and to some extent we see plenty of paradigm shifts. Women’s salaries are growing twice as fast as those of men, even though they only occupy a mere 21.4 percent of executive positions and despite the fact they hold most of the doctoral degrees in the country (51.5 percent) and dominate the area of research (58.6 percent). Women also own more companies in the Latin American region (11 percent) than any other emerging country. The new shifts in the Brazilian economy also benefit the black communities, which have seen their salaries increase four times faster than their white counterparts, bringing the population of the middle class blacks from 39.3 percent to 50.9 percent. According to research conducted by the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, of 20.6 million people who entered the workplace, only 7.7 million were white. Overall, the country is enjoying the boom brought by commodities, in particular oil and gas, despite the global economic slowdown. Are advanced economies entrepreneurs taking advantage of this?

If not, they should, but with a caveat. We believe what worked for the Brazilian economy ten even twenty years ago, such as a focus on commodities, low labor costs, and excessive focus on exports, won’t work moving forward. Today, Brazil is a new country, with new habits and customs, and believe it or not, a population that possesses an extremely elevated self-esteem. Meaning, the fledgling and rapidly growing Brazilian middle class, 52 percent of the population since 2008, is in love with itself and ready to spend. According to Goldman Sachs, more than two billion people around the world will belong to the middle-class by 2030, but the majority of Brazilians are already there.

In 2010, the United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) report, ranked Brazil-among the ten worst countries in the world in terms of income inequality, with a Gini* Index of 0.56 (one being ideal and zero being the worst), tied with Ecuador and only better than Bolivia and Haiti. Brazil is home to 31 percent of all Latin American millionaires, about five thousand people with a net worth superior of $30 million. More than 100 thousand Brazilians own financial investments of at least one million reais, or about $500 thousand. But what this report fails to include is that in 2008 the Gini index was far worse: 0.515. Since then, 2010 data indicates unemployment fell from 12.3 percent to 6.7 percent and, as mentioned earlier, it is now at 4.9 percent. In 2003 there were 49 million Brazilians living in poverty. Six years later that number plummeted to 29 million as a result of government sponsored social programs.

Brazil’s primary challenge is in regard to education. In our view, the global economy has essentially become a knowledge economy. However, Brazil has not adequately invested in education, despite the commodities boon. Recently, the federal government launched several promising educational programs, such as “science without barriers,” a program that finances and sends several thousand higher education students abroad in the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) disciplines. Sadly though, the reality today is that approximately 80 percent of all corporate professionals in Brazil do not have a college degree—one of the lowest rates in the world.

According to a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) report, only 35 percent of Brazilians between the ages of 25 and 34 have high school diplomas, which is three times higher than those between the ages of 55 and 64 years of age. The new generation of professionals is not being educated quickly enough. Compare this data to South Korea, which planned for its economic growth by increasing the number of high school graduates from 35 to 97 percent. As of March 2013, the U.S. number was 75 percent. Still, in the past five years, there have never been as many Brazilians studying. In the past 10 years, 435 vocational schools were opened, and the number of universities jumped from 1800 to almost 3,000 institutions, while the number of college students jumped 46 percent, reaching 6.5 million. By comparison, the United States has 4,495 Title IV-eligible institutions, and about 20.3 million college students. As we look toward the future, despite all its shortcomings, we are looking at a much more educated workforce in Brazil.

Until now, Brazilians did not believe in their country’s potential and suffered from a certain inferiority complex. Now, they have several reasons to take pride in being Brazilian: the impressive economic boom of late, greater access to education and to information (Brazil is fifth in the world in Internet access, behind only China, United States, India, and Japan), a democratization of the culture, and the recognition of Brazil as an emerging country abroad.

While there are a variety of different methodologies being used to study the relatively new field of Happiness Economics, or the efficiency with which countries convert the earth’s finite resources into happiness or well-being measures. The think tank company Global Finance has ranked 151 countries across the globe on the basis of how many long, happy and sustainable lives they provide for the people who live in them per unit of environmental output. The Global Happy Planet Index16 (HPI) incorporates three separate indicators, including ecological footprint, or the amount of land needed to provide for all their resource requirements plus the amount of vegetated land needed to absorb all their CO2 emissions and the CO2 emissions embodied in the products they consume; life satisfaction, or health as well as “subjective well-being” components, such as a sense of individual vitality, opportunities to undertake meaningful, engaging activities, inner resources that help one cope when things go wrong, close relationships with friends and family, or belonging to a wider community; and life expectancy. According to the report results, Brazil ranks 21, while the United States is 105. (Costa Rica leads the way and Vietnam is second.) Need we say more?

* The concept of economic freedom, or economic liberty, denotes the ability of members of a society to undertake economic direction and actions. This is a term used in economic and policy debates as well as a politico economic philosophy. One major approach to economic freedom comes from classical liberal and libertarian traditions emphasizing free markets, free trade and private property under free enterprise, while another extends the welfare economics study of individual choice, with greater economic freedom coming from a “larger” set of possible choices.

* In Atlas Shrugged’s John Galt’s manifesto.

* The term Abenomics is a portmanteau of “Abe” and “economics,” which refers to the economic policies advocated by Shinzō Abe, the current Prime Minister of Japan.

* The Maastricht Treaty (formally, the Treaty on European Union or TEU) was signed on 7 February 1992 by the members of the European Community in Maastricht, Netherlands. On 9–10, December 1991, the same city hosted the European Council which drafted the treaty. Upon its entry into force on 1 November, 1993 during the Delors Commission, it created the European Union and led to the creation of the single European currency, the euro.

† 1990–1999. The history of the European Union—1990–1999. Europa. Last accessed on September 11, 2011.

* A category within the money supply that includes M1 in addition to all time-related deposits, savings deposits, and non-institutional money-market funds. M2 is a broader classification of money than M1. Economists use M2 when looking to quantify the amount of money in circulation and trying to explain different economic monetary conditions. SOURCE: Investopedia, http://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/m2.asp.

† The portion (expressed as a percent) of depositors’ balances banks must have on hand as cash. This is a requirement determined by the country’s central bank, which in the United States is the Federal Reserve. The reserve ratio affects the money supply in a country. This is also referred to as the “cash reserve ratio” (CRR). SOURCE: Investopedia, http://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/reserveratio.asp.

* A monthly index of manufacturing, considered one of the most reliable leading indicators available to assess the near-term direction of an economy. An index reading above 50 percent indicates that the manufacturing sector is generally expanding, while a reading below 50 percent indicates contraction. The further the index is away from 50 percent, the greater the rate of change.

* From 2001 until 2013, Brazil’s unemployment rate averaged 8.8 percent reaching an all time high of 13.1 percent in April of 2004 and a record low of 4.6 percent in December of 2012.

* The Gini index is a measure of statistical dispersion intended to represent the income distribution of a nation’s residents. It was developed by the Italian statistician and sociologist Corrado Gini.

* Ibidem.

*http://www.heritage.org/index/country/unitedstates

* Ibidem.

† Ibidem.

‡ Ibidem.

‡ Ibidem.