Overview

That global trade imbalance matter has been made abundantly clear by the ongoing global economic malaise. The likely path to more sustainable levels of trade deficits, nevertheless, remains far less clear. Consider the potential global impact of populist cries for protectionist trade policies ostensibly aimed at easing the difficult transition to more sustainable trade and debt balances. In the event of a trade war, which we discussed in Chapter 5 and is already happening, we will all lose. Perhaps even more unsettling, however, is how these consequences would most likely manifest across nations. The evidence presented in this chapter suggests that countries like China, which depend heavily on total trade in relation to their overall economy, could suffer most severely. This evidence further suggests that instead of pursuing short-term quick fixes that would exacerbate the malady, global policymakers must work together to establish a long-term path to more sustainable trade and debt balances.

Many take as fact that the current pattern of global imbalances, or the large and persistent trade deficits and surpluses across different parts of the world, ultimately unsustainable, is due to China and ASEAN consuming too little and saving too much. Since the global economy is a closed trading system, trade deficits and surpluses across all national economies must always sum exactly zero. Therefore, because one part of the world saves too much and runs trade surpluses means other parts of the world, particularly the United States, must run trade deficits.

However, just because deficits and surpluses are tightly inter-connected it does not mean that trade surpluses in China or ASEAN, for instance, have been responsible for United States and EU trade deficits. In addition, China’s high level of savings might be dynamically welfare optimizing for its citizens. Note also that private enterprise in China might find self-accumulation the only way to generate investment funds.

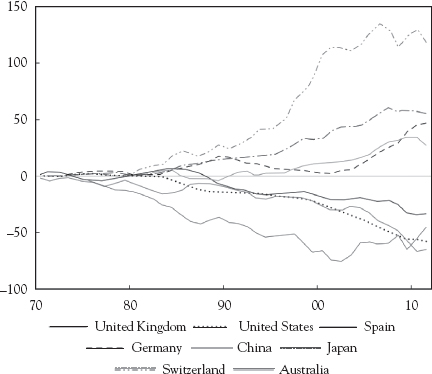

The fact remains that countries with a current account surplus, as depicted in Figure 6.1, must also be those with exports in excess of imports, as shown in Figure 6.2. The range of imbalances among these nations has widened dramatically in recent decades, leading to a very unsustainable path. Notice in Figure 6.1 that Switzerland, Germany, and China currently enjoy the largest net trade surpluses, while the United States, the United Kingdom, and Spain have the largest net deficits.

The magnitude of trade deficits matters because a country with an ongoing trade deficit is, by definition, reducing its foreign assets or borrowing. Not as well understood is that global trade patterns are financed by gross asset flows, not net asset flows. Hence, a country must have sufficient gross foreign assets to finance any trade imbalance on an ongoing basis. Undeniably, these gross asset financial flows grease the skids of global trade. Practically speaking, trade deficits must be paid for by either selling down gross assets or increasing gross liabilities by selling debt.

Despite the many theories and conjectures offered, the global economy continues to struggle as it attempts to recover, slowly and painfully, from the financial crisis it entered in 2007. According to the IMF’s July 2012 report, for example, world output growth—expressed at market exchange rates—will be roughly 2.5 percent in 2013 and about 0.5 percent faster in 2014. These rates of growth are concerning, and are far slower than those that preceded the crisis, although they are still positive. Meanwhile, China’s economic growth continues to sputter, even if at a lower rate. The euro is still under threat, and the United States is still combating serious trade disadvantages.

In our view, the EU’s underlying problem is not budget deficits or even unsustainable debt; these are mainly symptoms. The main problem with the EU is the huge divergence in costs between the core and the periphery. In the past decade costs between Germany and some of the peripheral countries have diverged by anywhere from 20 percent to 40 percent. This divergence has made the latter uncompetitive and has resulted in the massive trade imbalances within Europe.

Trade imbalances, of course, are the obverse of capital imbalances, and the surge in debt in peripheral Europe, which is debt owed ultimately to Germany and the other core countries, was the inevitable consequence of those capital flow imbalances. While EU’s policymakers alternatively worry over fiscal deficits, surging government debt, and collapsing banks, there is almost no prospect of their resolving the European crisis until they address the divergence in costs. Of course if they don’t resolve this problem, the problem will be resolved for them in the form of a break-up of the euro.

There is no doubt that trade deficits and surpluses narrowed significantly during this so-called great recession.* The economic activity in the advanced economies, mainly the G-7 nations, fell by five percent, while the number of unemployed people around the world surged by more than 30 million.2 The global economy contracted by 0.8 percent in 2009, but it rebounded strongly in the next two years as central banks around the world, led by the U.S. Federal Reserve, embarked on massive monetary stimulus programs.*

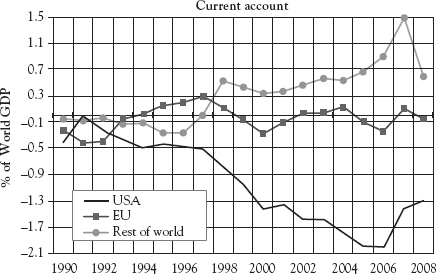

As depicted in Figure 6.3, the situation was so dire that in November of 2010, at the G-20 meeting in Seoul, the United States and other G-7 member countries running high external deficits challenged those countries that maintain surpluses: China, Germany, and Japan, along with other smaller emerging countries, to pick up the slack in global demand. Predictably, this effort brought no tangible results.

Although we believe a global rebalance is to some extent necessary to reduce trade deficits and surpluses, we argue that too much emphasis on that may not be healthy for the global economy. Focusing too much on rebalancing the global economy can actually be ill advised. Mind you, this is not a book on international economics; none of the authors are economists. But from the point of view of international trade and foreign affairs, global rebalance should be viewed as an idea, an overall goal, and not as a task, or a mission.

For starters, emerging markets remain heavily dependent on consumer demand in the United States and Western Europe. If this consumer demand grows more slowly in the future, due to the unwinding of household debts, the influence of higher risk premium on investment, and the effect of rising national debt on government expenditures, would the export-led emerging market economies continue to grow? The answer to this question is critical, as it directly impacts strategies that will need to be in place to stimulate domestic demand for the four billion people in the emerging markets.

In the same way, assuming a rebalancing of the global trade is a realistic strategy, what would be the impact of such rebalancing trade flows across the different emerging markets, such as the ASEAN, CIVETS, MENA, and BRICS? Who is more likely to gain, or lose, from such rebalancing, and what should the policy response, according to these countries’ different economic structures, degrees of openness, and socio-political institutions look like?

Furthermore, assuming global trade and capital flows were rebalanced sustainably, what implications would this have for the future of reserve currencies around the world? Can the U.S. dollar retain its reserve currency status while enabling global financial capital to flow to the most profitable investment opportunities and global trade to flow where it is needed most? Lastly, what reserve currency regime is required for sustainable trade and capital flows? These questions are not easily answered.

While Michael Pettis4 argues that the global economy is already undergoing a critical rebalancing, he points out that that the severe trade imbalances impelled on the recent financial crisis was the result of unsuccessful policies that distorted the savings and consumption patterns of some nations, mainly G-7.* Pettis cautions about the yet to be seen consequences of these destabilizing policies, predicting severe economic dislocations in the upcoming years. He warns of a lost decade for China, the breaking of the Euro, and a continuing decline of the U.S. dollar, all with long-lasting effects.

In Pettis’ views, there are myriad causes for his dismal global outlook and economic prospect. He points to China’s maintenance of massive investment growth by artificially lowering the cost of capital, which he warns to be unsustainable. He worries that Germany is endangering the euro by favoring its own development at the expense of its neighbors’ states. He also argues that the U.S. dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency burdens the American economy. Pettis suggests that while many of these various imbalances may seem unrelated, including the U.S. consumption splurge, the surging debt in Europe, China’s investment debauch, Japan’s long stagnation, and the commodity boom in Latin America, they are all closely tied together, making any attempt to rebalance the global economy impossible, unless each of the domestic issues (for both G-7 and G-20) are resolved. Moreover, he argues that it will be impossible to resolve any issue without forcing a resolution for all.

In our opinion, policymakers around the world, mainly between the G-7, are focusing too much effort on global rebalancing, which, in our view, only encourages currency tensions, such as the current one between China and the United States and, ominously, contributes to mounting protectionist sentiment and tensions. Such efforts also divert attention from most importantly, the needs for reforms at home. We argue that, rather than focusing on global rebalancing, the G-7 nations, and to some extent the G-20, should concentrate more on repairing their domestic problems and expanding their domestic demand at the maximum sustainable rate.

We are of the position that a major rebalancing of global demand, or more explicitly, a decrease of aggregate demand in deficit countries relative to that of surplus countries must occur, to foster smaller trade deficits and surpluses, which has already occurred during the great recession. Global demand has already undergone a major rebalancing during 2008–2009 as a consequence of the global credit crunch.

As depicted in Figure 6.4, countries with large current account deficits, such as the United States and Spain, also experienced the biggest housing bubbles and have the most indebted consumers, forcing government authorities to cut much more spending than surplus countries did. Hence, for all the reasons aforementioned, we argue that a long-term trend toward rebalancing, as promoted by G-7 nations, is very unlikely to happen.

The idea may be popular among the G-7 group, but we don’t believe it will gain traction among the G-20. As advanced economies, without much success so far, continue to pressure emerging markets to engage in rebalancing, the G-7, particularly the United States, may be forced to take a stand: either tackle the profound domestic vulnerabilities that have been exposed, or put at risk the open, rules-based trading system that has bolstered significant postwar prosperity.

Figure 6.4 Nations with largest current Account surpluses and deficits

Source: IMF, Carnegie Endowment5

Despite the challenges of rebalancing the global economy, we identify three great challenges confronting the global recovery. The first one is the exiting stimulus policies in the United States. The first phase of the stimulus exit, widely known as the large fiscal contraction, or “fiscal cliff,” appears to have survived without significant damage to consumers and investment demands. The second phase of this stimulus exit still lies ahead in the future, when the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank begins to reduce its bond purchases. Judging by the near panic in the financial markets following a speech by Chairman Bernanke in the fall of 2013 announcing its imminence, this second phase may prove to be problematic. Yet, the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank remains sensitive to the fact that unemployment remains high, as such is determined to ensure that monetary tightening will only occur in response to clear signs that the economy is strengthening.

The second challenge is to avoid the sharp slowdown in emerging markets in the past couple years (2012–2013), particularly in China, from collapsing. Growth has slowed precipitously in the BRICS and ASEAN, among others. Yet, even with this slowdown, we believe emerging markets as a group will continue to benefit from technological advancements, high savings rates, significant investments in education, and favorable demographics, including an ever increasing middle-class. Despite the global crisis, emerging markets are still growing at an average rate of five percent. China suffers from overly large and misallocated credit-fueled investments as well as inadequate demand by households. As its huge reservoir of surplus labor depletes, China’s wages are now rising fast, pointing to a country less competitive in international markets and more inclined to consume. China is unlikely to return to the fiery 9–W10 percent growth of the last three decades, but its solid fiscal position, robust household balance sheets, and huge reserves suggest it will find a way to sustain a more moderate pace and continue to support the global recovery.

The third and greatest challenge is to complete the extremely painful adjustment of the EU’s periphery. Countries such as Greece, Spain, and Italy need to regain international competitiveness and reorient the economy away from domestic activity, such as construction and public services, and more toward exports and import-substitutes, such as manufacturing and tourism. This is now happening at a steady if unspectacular pace and is reflected in sharply lower current account deficits. For instance, in 2012 and 2013, exports in Italy and Spain grew in line with world trade*, while imports fell about three times faster than GDP.

In sum, how should global trade imbalances rebalance? The inexorably deleveraging of current large trade deficits has been damaging and requires global cooperation to put into place a credible fiscal plan to bring down deficits deliberately. Such alternative solutions as monetary policy alone will continue to prove insufficient, and seeking a solution by waging a trade war should be fiercely resisted. Following such quick-fix paths could produce severe consequences for the global economy, and heavily trade-dependent countries would feel the impact even more harshly.

* Ibidem.

* The great recession refers to the global contraction from December 2007 to June 2009 that resulted in the world economy shrinking for the first time since 1945. The Great Recession was so-called because its severity and depth made comparisons with the Great Depression of the 1930s inevitable.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Around 2.5/3 percent.