Dealing with Corruption and Crime

Overview

For the last 20 years, we have witnessed rapid development in the effort to combat corruption under international law, as we now live in a world where, according to Transparency International,1 and as illustrated in Figure 14.1, more than one in four people report having paid a bribe. International criminals and dishonest businessmen don’t hesitate to make use of loose regulatory systems put in place by politicians in certain “safe haven” countries around the world to attract capital.

Currently two regional anti-corruption conventions are in force. The first convention was negotiated and adopted by the members of the Organization of American States (OAS),2 while the second was adopted under the auspices of the OECD.* In addition, a number of international organizations are vigorously working on developing appropriate anti-corruption measures. These groups include several bodies within the UN, the EU, IBRD, also known as the World Bank Group (WB). Also involved are several nongovernmental organizations, such as Transparency International and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC).

Figure 14.2 provides the perceived corruption levels by country and companies’ propensity for bribery. The higher the score means fewer propensities to bribe.

Figure 14.1 More than one in four people around the world report having paid a bribe

Source: Transparency International

Figure 14.2 The perceived corruption levels by country and companies’ propensity to bribe

Source: Transparency International

When journalists with the Center for Investigative Journalism in Bucharest, Romania started investigating a gold mining operation in the village of Rosia Montana, in the heart of Transylvania, they didn’t know they would soon be looking at a far wider web of corruption that linked commercial enterprises on five continents. The name of a company and the name of its founder led the journalists to Russian oligarchs, officials in Eastern European governments, former employees of well-known corporations, and even NATO* officials.

The tangled network of connections unraveled as journalists looked deeper and deeper at corporate records in over 20 countries. Company records exposed the connections between former Communist government officials and devious, western-based companies. They also revealed that big chunks of Eastern European economies are still handled by former employees of the Communist Secret Services.

In another example, a name on a corporate record in Bulgaria led to an investigation involving the Irish Republican Army’s (IRA) money laundering through purchases of real estate on the shores of the Black Sea. A company record in Hungary led to one of the most powerful Russian organized crime bosses and his questionable interests in the natural gas industry.

When we consider these examples, and there are numerous news outlets around the world showcasing many more, we also must consider ways of responding to the challenges of dealing with international corruption and crime, not only as international business investors and professionals, but also as a responsible global society. Corruption not only disrupts businesses, but also generates social imbalances and poverty. The international response to corruption, therefore, raises many important questions:

Could global corruption and crime be a manifestation of oppression around the world?

•Is the anti-corruption movement a global outcry against the abuse of power?

•Is the pressure on trade competition around the globe promoting corruption?

•Is global corruption a result of globalization?

•Is the anti-corruption movement a consequence of a renewed sense of morality around the world?

•Should global corruption be a concern for international law?

While certainly provoked by these questions, this chapter does not pretend to give definitive answers. It seeks only to contribute to the understanding of the development of anti-corruption measures under the international law, since, according to the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), corruption today is one of the main threats to global development and security.* Corruption and crime often is considered the negative side of globalization as international crime has been rapidly capitalizing on the expansion of global trade and broadening its range of activities. Several criminal groups, organized as multinational companies, are often seeking profits through the evaluation of countries’ risks, benefits, and markets analysis.

The Challenges of Combating Corruption Around the World

For entities fighting crime and corruption around the world, one of the main challenges, therefore, consists of preventing such groups from continuously adapting to the changes at local and international levels. It is important to disrupt the creation of intercontinental networks, prevent them from diversifying their activities, and taking advantage of the potential offered by globalization. These factors are the main obstacles for all entities around the world fighting organized crime. Furthermore, the lack of judicial and enforcement tools plays a strategic role in the growth of global criminal syndicates’ management of trafficking drugs, arms, human beings, counterfeiting, and money laundering.

Under the veil of banking and commercial secrecy laws, huge amounts of money exchange hands in havens outside jurisdiction scrutiny of the source countries. Capital cycled through such dealings can be transformed into real estate, bonds, or other goods and then moved back into the country or to other global markets legitimately. Such transactions are looked closely at by international law enforcement because they raise suspicion of money laundering associated with organized crime and terrorism.

Although off-shore havens are usually associated with tropical islands somewhere in the Caribbean, in many instances countries such as Austria, Switzerland, or the United States have off-shorelike facilities that enable businesses and individuals to hide ownership and deter investigators from finding out who owns companies that are involved in crooked deals.

Organized crime figures would rather use private foundations (Privatstiftungs) in Austria, or companies in the state of Delaware in the United States, than companies in the British Virgin Islands (BVI), the Isle of Man, Aruba, or Liberia, known as safe havens that the media and law enforcement have associated as a places for money laundering. The mere mention of any of these places can mark a red flag on a transaction that is then monitored by international law enforcement.

All over the world, organized crime adopts all forms of corruption to infiltrate political, economic, and social levels. Although strong institutions, in particular government ones, are supposed to be impermeable to corruption, weak governance often coexists with corruption and a mutually causal connection exists between corruption and feeble governmental institutions and often ends up in a vicious cycle. Thus, well-known offshore havens are fighting to clean up their names and show that proper control mechanisms are in place. It should be mentioned that in most cases such jurisdictions are now used for tax purposes.

For instance, Liechtenstein, a European country of 35,000 people located in the Alps, was hit hard in the beginning of 2008 when data stolen by a former bank employee was sold to law enforcement agencies in many European countries. The data showed that wealthy citizens from many countries had used Liechtenstein’s banks in tax evasion schemes. As a result of the leak, the German authorities who bought the disks managed to recover over US$150 million in back taxes within months of obtaining the data. The United States, Canada, Australia, and the EU countries are also in possession of the same data and they are independently pursuing their own investigations into tax evasions involving banking in the tiny country.

The scandal not only shook Liechtenstein’s political relationships with other countries but spread to Switzerland and Luxembourg, two other European countries that have a record of bank secrecy and nontransparent financial transactions. The head of the Swiss Bankers’ Association, Pierre Mirabaud, was so outraged by the fact that the stolen data ended up in German law enforcement’s hands that he said in an interview with a Swiss TV station that the German investigators’ methods reminded him of Gestapo practices, referring to the secret police of Nazi-era Germany. He later apologized for the unfortunate comparison. Just like Liechtenstein, Cyprus has been blamed many times for harboring money from organized crime groups and former communist officials from Eastern European countries.

The growing problem of offshore havens, corruption, and crime, and the damage they bring to the global economy, has been pointed out repeatedly in the context of the global financial crisis. The OECD together with French and German government leaders vowed to make the offshore industry disappear. They called the offshore areas the black holes of global finance.3 The offshore company formation industry, however, is kept alive by scores of lawyers, incorporation agents, and solicitors. They advertise complex business schemes to maximize returns and minimize taxation.

Take for example the website http://www.off-shore.co.uk/faq/company-formation/ which explicitly presents potential customers with the possibility of hiding real ownership of a company behind a nominee shareholder or director. According to the site’s frequently asked questions (FAQ) section, “A nominee shareholder or director is a third party who allows his/her name to be used in place of the real or beneficial owner and director of the company. The nominee is advised particularly in those jurisdictions where the names of the officers are part of a public record, open for anyone who cares to look can find out these identities. The name of the nominee will appear and ensure the privacy of the beneficial owner.”

The primary role of such company formation schemes is to avoid paying taxes. However, some countries go to extremes when they try to hide the real beneficial owners. Panama and Liberia are among the countries that go to great lengths to preserve the anonymity of company owners. Under Panamanian law, an S.A. corporation* can be owned by the physical holder of certificates or shares, with no recorded owner in any database or public registry. In fact, there is no public registry in Panama, so the government does not even know who owns shares in corporations. Shares can exchange hands at any time and the beneficial owners are impossible to trace through public records.

Discerning the ownership of companies trading around the world has become increasingly complex. A company in Belgrade, Serbia, could be owned by a firm in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, which could in turn be owned by a private foundation in Austria that has Russian oligarchs as its beneficial owners. This is a common scheme. Investigative journalists in the Balkans have identified schemes as complicated as twenty layers of companies. Searches performed for names of such companies often lead to lawyers or designated shareholders. But this should not be seen as a dead or a fait accompli. Organized crime figures quite often rely on the same lawyers or the same formation agent when they establish new companies to limit the number of people aware of their moves. Once a lawyer or straw party is identified, searches of the lawyer’s name can be performed on various databases. This could reveal dozens or hundreds of companies associated with the solicitor’s name.

Therefore, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, corruption is a challenge not only for emerging markets but also for advanced economies. In the United States, as a result of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) investigations in the mid-1970s, over 400 U.S. companies admitted making questionable or illegal payments in excess of $300 million dollars to foreign government officials, politicians, and political parties. The abuses ran the gamut from bribery of high foreign officials to securing some type of favorable action by a foreign government to so-called facilitating payments that were made to ensure that government functionaries discharged certain ministerial or clerical duties.

One major example is the aerospace company Lockheed bribery scandals, in which its officials paid foreign officials to favor their company’s products.4 Another example is the Bananagate scandal in which Chiquita™ Brands bribed the president of Honduras to lower taxes.5

Congress enacted the FCPA, which is discussed in more detail later in this chapter, to bring a halt to the bribery of foreign officials and to restore public confidence in the integrity of the American business system. The Act was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on December 19, 1977, and amended in 1998 by the International Anti-Bribery Act of 1998, that was designed to implement the anti-bribery conventions of the OECD. The FCPA makes it a crime for any American citizen and business to bribe foreign public officials for business purposes. It also imposes certain accounting standards on public U.S. companies.

Being poor not only means falling below a certain income line. Poverty is a multi-dimensional phenomenon that is often characterized by a series of different factors, including access to essential services (health, education, sanitation, and so on.), basic civil rights, empowerment, and human development.6 Corruption undermines these development pillars, an individual’s human rights, and the legal frameworks intended to protect them. In countries where governments can pass policies and budgets without consultation or accountability for their actions, undue influence, unequal development, and poverty result.7 People become disempowered (politically, economically, and socially) and, in the process, further impoverished.

In a corrupt environment, wealth is captured, income inequality is increased, and a state’s governing capacity is reduced, particularly when it comes to attending to the needs of the poor. For citizens, these outcomes create a scenario that leaves the poor trapped and development stalled, often forcing the poor to rely on bribes and other illegal payments in order to access basic services. Multiple and destructive forces take roots in corrupt country: increased corruption, reduced sustainable growth, and slower rates of poverty reduction.*† As warned by the World Bank, corruption is “the greatest obstacle to reducing poverty.” This growing socio-economic inequality causes the loss of confidence in public institutions. Social instability and violence increase because of growing inequality, poverty, and abject mistrust of political leaders and institutions.

When it comes to income inequality, even Alan Greenspan is worried about this troubling trend. As argued by Chrystia Freeland, a Canadian international finance reporter at Thompson Reuters, in her book Plutocrats,8 there has always been a gap between rich and poor in every country around the globe, but recently what it means to be rich has changed dramatically. Forget the one percent as is commonly believed; Plutocrats prove that it is the wealthiest 0.1 percent who are outpacing the rest of us at breakneck speed. Most of these new fortunes are not inherited; they are amassed by perceptive businesspeople that see themselves as deserving victors in a cutthroat competitive world. In her book, Freeland exposes the consequences of concentrating the world’s wealth into fewer and fewer hands.

The question Freeland raises is whether the gap between the superrich and the rest is the product of impersonal market forces or political machinations. She draws parallels between current inequality and the Gilded Age of the late 1800s, when the top 1 percent of the U.S. population held one-third of the national income. Globalization and the technological revolutions are the major factors behind what she sees as new and overlapping Gilded Ages: the second for the United States, the first for emerging markets. Drawing on interviews with economists and the elite themselves, Freeland chronicles hand wringing over the direction of the global economy by these 0.1 percent plutocrats around the world. As she laments, the feedback loop between money, politics, and ideas is both cause and consequence of the rise of the super-elite.

Corruption, therefore, often accompanies centralization of power, when leaders are not accountable to those they serve. More directly, corruption inhibits development when leaders help themselves to money that would otherwise be used for development projects. Corruption, both in government and business, places a heavy cost on society. Businesses should enact, publicize, and follow codes of conduct banning corruption on the part of their staff and directors. Citizens must demand greater transparency on the part of both government and the corporate sector and create reform movements where needed.

Corruption on the part of governments, the private sector, and citizens affect development initiatives at their core root by skewing decision-making, budgeting, and implementation processes. When these actors abuse their entrusted power for private gain, corruption denies the participation of citizens and diverts public resources into private hands. The poor find themselves at the losing end of this corruption chain— without state support and the services they demand. The issue of corruption is also very much inter-related with other issues. On a global level, the economic system that has shaped the current form of globalization in the past decades requires further scrutiny for it also has created conditions whereby corruption can flourish and exacerbate the conditions of people around the world who already have little say about their own destiny.

Corruption is both a major cause and a result of poverty around the world. It occurs at all levels of society, from local and national governments, civil society, judiciary functions, large and small businesses, military, and other services and so on. Corruption, nonetheless, affects the poorest the most, whether in rich or poor nations.

It is difficult to measure or compare, however, the impact of corruption on poverty against the effects of inequalities that are structured into law, such as unequal trade agreements, structural adjustment policies, free trade agreements, and so on. The reality is that corruption and crime generate a lot of poverty around the world, especially among the LDC. A list of the top 50 is depicted in Figure 14.3.

To identify corruption is not difficult, but it is harder to see the layers it can have, especially under the more formal, even legal forms of corruption. It is easy to assume that these formal forms are not even an issue because they are often part of the laws and institutions that govern national and international communities of which many of us are accustomed to. If a president of an emerging country gets paid a bribe and as a result taxes are reduced to benefit certain corporations or even markets, what do we, the general public, know?

Figure 14.3 The 50 least developed countries in the world

Source: UNCTAD

Corruption promotes, and often determines, the misuse of governments’ resources by diverting them from sectors of vital importance such as health, education, and development. Hence, the people who have the most needs, the poor people, are the ones deprived of economic growth and development opportunities, which in turn causes significant income inequalities and lack of social mobility. Corruption also siphons off goods and money intended to alleviate poverty. These leakages compromise a country’s economic growth, investment levels, poverty reduction efforts, and other development-related advances.

At the same time, petty corruption saps the resources of poor people by forcing them to offer bribes in exchange for access to basic goods and services—many of which may be free by law, such as health care and education. With few other choices, poor people may resort to corruption as a survival strategy to overcome the exclusion faced when trying to go to school, get a job, buy a house, vote, or simply participate in their societies. Consequently, the cost of public services rises to the point where economically deprived people can no longer afford them. As the poor become poorer, corruption feeds poverty and inequality.

Combating poverty and corruption, therefore, means addressing and overcoming the barriers that stand in the way of citizen engagement and a state’s accountability. While most emerging economies claim that the equal participation and rights of citizens exist, in reality they rarely apply to the poor. Hence, to be effective, pro-poor anti-corruption strategies must look more closely at the larger context that limits opportunities for poor citizens to participate in political, economic, and social processes.

The Importance of Political Participation and Accountability

Corruption in the political sphere attracts growing attention in more and more countries. The demand for accountability of political leaders and the transparency of political parties has begun to trigger reform in those areas. Private businesses also have become a focus of anti-corruption reform. Besides being the object of state oversight, this sector has started its own initiatives to curb corruption.

Linking the rights of marginalized communities and individuals to seek government’s accountability is a fundamental first step for developing a pro-poor anti-corruption strategy. Citizens giving their governments the power to act on their behalf shape a country’s policies. Corruption by public and private sector officials taints this process, distorts constitutions and institutions, and results in poverty and unequal development. Strengthening political accountability would result in policies that ensure that the poor are seen not as victims but rather as stakeholders in the fight against corruption. For now, a consensus on how to strengthen these elements into action remains elusive within development cooperation circles.9

Notwithstanding the large differences in the problems prevalent in various countries and the existing remedies, it is satisfying to see efforts to prevent corruption target similar areas across the region. Most countries that have endorsed the OECD’s Anti-Corruption Action Plan, for example, attribute an important role to administrative reforms. Hence, the various strategies to prevent corruption address integrity, effective procedures, and transparent rules.

The integrity and competence of public officials are fundamental prerequisites for a reliable and efficient public administration. Many countries in the OECD region have subsequently adopted measures that aim to ensure integrity in the hiring and promoting of staff, provide adequate remuneration, and set and implement clear rules of conduct.

Past and current efforts to reduce poverty suggests that corruption has been a constant obstacle for countries, particularly emerging economies, trying to bring about the political, economic and social changes desired for their development. Across different country contexts, corruption has been a cause and consequence of poverty. At the same time, as depicted in Figure 14.4, corruption is a by-product of poverty. The poorest countries in the world, already marginalized, tend to suffer a double level of exclusion in countries where corruption characterizes the rules of the game. Interestingly enough, oil-producing countries also make the list.

The Foreign Corrupt Practice Act

The FCPA of 1977 is a U.S. federal law known primarily for two of its main provisions. One that addresses accounting transparency requirements under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and the other concerning bribery of foreign officials.* It was enacted in the surge of public morality following the Watergate Scandal and in response to a U.S. congressional investigation uncovering widespread bribery among domestic companies operating overseas.

The FCPA applies to any person who has a certain degree of connection to the United States and engages in foreign corrupt practices. As argued by Alexandro Posadas,10 of Duke University, the Act governs not only payments to foreign officials, candidates, and parties, but also any other recipient if part of the bribe is ultimately attributable to a foreign official, candidate, or party. These payments are not restricted to monetary forms and may include anything of value.*

The meaning of foreign official, however, is broad. For example, an owner of a bank who is also the minister of finance is considered a foreign official according to the U.S. government. Doctors at government-owned or managed hospitals are also considered to be foreign officials under the FCPA, as is anyone working for a government-owned or managed institution or enterprise. Employees of international organizations such as the United Nations are also considered to be foreign officials under the FCPA.

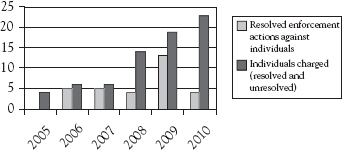

Individuals subject to the FCPA include any U.S. or foreign corporation that has a class of securities registered (public trade companies), or that is required to file reports under the Securities and Exchange (SEC) Act of 1934. The SEC actually has increased the level of FCPA action, as shown in Figure 14.5, from 17 cases in 2007 to 20 cases in 2011.

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), as depicted in Figure 14.6, has ramped up enforcement of the FCPA against individuals. In 2005, less than five individuals were prosecuted, but by 2010 more than 22 individuals were charged with violation. As an example, the former U.S. representative William J. Jefferson, democrat of Louisiana, was charged with violating the FCPA for bribing African governments for business interests.11

Figure 14.5 FCPA actions brought by the SEC

Figure 14.6 Increase in DOJ enforcement of FCPA against individuals

Note: 2010 statistics through April 1, 2010.

The FCPA also requires companies whose securities are listed in the United States to meet its accounting provisions.* These accounting provisions, which were designed to operate in tandem with the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA, require corporations covered by the provisions to maintain records that accurately and fairly reflect the transactions of the corporation and to devise and maintain an adequate system of internal accounting controls. An increasing number of corporations are taking additional steps to protect their reputation and reduce exposure by employing the services of due diligence companies. Identifying government-owned companies in an effort to identify easily overlooked government officials is rapidly becoming a critical component of more advanced anti-corruption programs.

Regarding payments to foreign officials, the act draws a distinction between bribery and facilitation or grease payments, which may be permissible under the FCPA but may still violate local laws. The primary distinction is that grease payments are made to an official to expedite his performance of the duties he is already bound to perform. Payments to foreign officials may be legal under the FCPA if the payments are permitted under the written laws of the host country. Certain payments or reimbursements relating to product promotion also may be permitted under the FCPA.

Recent changes to the U.S. FCPA now allow individuals to potentially collect millions of dollars by reporting corruption in U.S. companies or any company traded on U.S. exchanges. If a person knows of any improper payments, offers, or gifts made by a company to obtain an advantage in a business in the United States or abroad they are encouraged to report it. There are several law firms in the United States set up to assist whistleblowers in reporting their suspicions. There is no materiality to this act, making it illegal to offer anything of value as a bribe, including cash or noncash items. The government focuses on the intent of the bribery rather than on the amount.

Becoming a FCPA whistleblower may entitle the individual to receive substantial compensation, potentially millions of dollars. New changes in U.S. laws now allow individuals reporting FCPA violations to receive full protection from retaliation and collect up to 30 percent of the fines that the government collects. The U.S. government can fine companies up to US$2 million for each violation of the law. Thus for each payment made and each false record there may be a fine levied even if the payments are nominal. In 2010 the U.S. government collected over $1.5 billion in FCPA fines.

In addition, the Travel Act, enacted into law in 1961, forbids the use of travel and communications means to commit state or federal crimes. Ostensibly, it has been used to prosecute domestic crimes, such as the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act* (RICO) and gambling violations committed either by individuals or groups of persons.

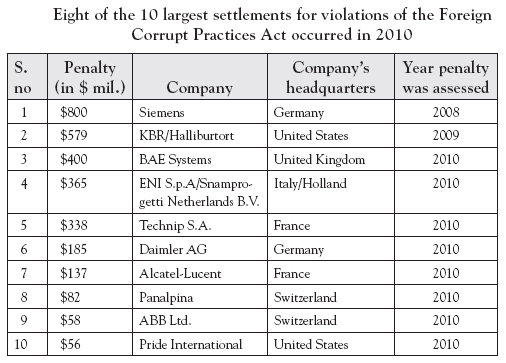

As depicted in Figure 14.7, some notable examples of FCPA violations include but are not limited to multinational corporations such as Walmart, BAE Systems, Baker Hughes, Daimler AG, Halliburton, KBR, Lucent Technologies, Monsanto, Siemens, TitanTM Corporation, Triton Energy Limited, Avon Products, and Invision Technologies.

In April of 2012 an article in The New York Times reported that a former executive of Walmart de Mexico alleged in September 2005 that Walmarts Mexican subsidiary had paid bribes to officials throughout Mexico in order to obtain construction permits. Investigators of Walmart actually found credible evidence that Mexican and American laws had been broken, which prompted Walmart executives in the United States to hush-up the allegations.12

Another article in Bloomberg argued Wal-Mart’s “probe of possible bribery in Mexico may prompt executive departures and steep U.S. government fines if it reveals senior managers knew about the payments and didn’t take strong enough action, corporate governance experts said.13” Eduardo Bohorquez, the director of Transparencia Mexicana, a “watchdog” group in Mexico, urged the Mexican government to investigate the allegations.14 Wal-Mart and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce had participated in a campaign to amend FCPA, where, according to proponents, the changes would clarify the law, while according to opponents, the changes would weaken the law.15

In 2008, Siemens AG paid a $450 million fine for violating the FCPA. This was one of the largest penalties ever collected by the DOJ for an FCPA case.16 The U.S. Justice Department and the SEC currently are investigating whether Hewlett Packard Company executives paid $10.9 million in bribery money between 2004 and 2006 to the Prosecutor General of Russia “to win a €35 million euros (US$47.86 million dollars) contract to supply computer equipment throughout Russia.17”

In July 2011, the DOJ opened an inquiry into the News International phone hacking scandal that brought down News of the World, the recently closed UK tabloid newspaper. In cooperation with the Serious Fraud Office in the UK, the DOJ is examining whether News Corporation violated the FCPA by bribing British police officers.18

In 2012, Japanese firm Marubeni Corporation paid a criminal penalty of US$54.6 million for FCPA violations when acting as an agent of the TKSJ joint venture, which comprised of Technip S.A., Snamprogetti Netherlands B.V., Kellogg Brown & Root Inc. (KBR), and JGC Corporation. Between 1995 and 2004, the joint venture won four contracts in Nigeria worth more than US$6 billion, as a direct result of having paid US$51 million to Marubeni for the purpose of bribing Nigerian government officials.19

In March 2012, Biomet Inc. a Warsaw, Indiana company paid a criminal fine of US$17.3 million in its settlement with the DOJ, and US$5.5 million in disgorgement of profits and prejudgment interest to the SEC.20 Biomet had bribed doctors at government hospitals in Argentina, Brazil, and China from 2000 to 2008. It paid out more than US$1.5 million and disguised the payments as commissions, royalties, consulting fees, and scientific incentives.

Johnson & Johnson also paid US$70 million in 2011 to settle criminal and civil FCPA charges for bribes to public sector doctors in Greece. Its subsidiary DePuy Inc. was charged in a criminal complaint with conspiracy and violations of the FCPA. A former DePuy executive in the UK, Robert John Dougall, was jailed for a year after he pleaded guilty in a London court to making £4.5 million pounds (US$7.36 million) in corrupt payments to Greek medical professionals.*

Other settlements for FCPA violations in 2012 include Smith & Nephew,21 who paid US$22.2 million to the DOJ and SEC, and BizJet International Sales and Support Inc.,22 who paid US$11.8 million to the DOJ for bribery of foreign government officials. Both companies entered into a deferred prosecution agreement.

FCPA Criticism

While the FCPA has the unquestionably noble goal of eliminating corruption and holding U.S. concerns to a high standard of morality, it has come under recent criticism for the substantial and, some would say, anti-competitive, costs that it imposes. In December 2011, the New York City Bar Association’s Committee on International Business Transactions issued a report critical of the FCPA, and, perhaps more significantly, its enforcement.23

The report noted that the FCPA imposes substantial compliance costs on companies subject to its jurisdiction—costs that their foreign competitors may not face. It also lamented the seemingly unchecked prosecutorial power to obtain huge settlements in FCPA cases, as the consequences of an FCPA indictment are potentially fatal to a company, and, as a result, most companies are willing to settle for large sums—regardless of whether they believe the allegations are valid. Indeed, as the report notes, in April 2011, each of the eight top fines for FCPA “violations” exceeded $100 million.

The report expressed concern that the U.S. DOJ is both prosecutor and judge in the FCPA context and that some U.S. companies have ceased foreign operations in the face of FCPA uncertainty. To that end, the report makes a number of recommendations to reign in the FCPA, such as adding a “willfulness” requirement before imposing liability on corporations, which currently can be criminally liable without having knowledge of the wrongful conduct, to ensure that only those companies that intend to violate the law are subject to the harsh fines, as well as a provision limiting a company’s successor liability for the premerger FCPA violations of a company that it acquired.

In an article titled State Hypocrisy on Anti-Bribery Laws, Stephan Kinsella* argues that the duplicity of

FCPA is blinding, as it makes it okay for the state to bribe (and extort and coerce) private business by means of threats, subsidies, tax breaks, and protectionist legislation, and okay for businesses to bribe elected officials (campaign contributions), and okay for the U.S. administration to bribe foreign governments, and okay for U.S. companies to be forced to pay bribes in the form of taxes, that are less than the amount of bribes they would have to pay to foreign officials, but not okay for U.S. companies to bribe foreign officials—even if this is customary and essential to “doing business” in that country, despite the fact this puts American businesses at a competitive disadvantage with companies from other countries that do not prohibit such bribery.

As Lew Rockwell,† former congressional chief of staff to U.S. senator Ron Paul, noted in his article Extortion, Private and Public: The Case of Chiquita Banana,24

Paying bribes and being subject to this kind of extortion is just part of what it takes to do business in many countries. This might sound awful, but the truth is that such payments are often less than the companies would be paying to the tax man in the U.S., which runs a similar kind of extortion scam but with legal cover.‡

In Rockwell’s opinion, American businesses are howling at the competitive disadvantage this Act imposes on them. Instead of repealing the FCPA Act, Rockwell argues the United States is using its legislative imperialism to force other countries to adopt similar laws, while twisting the arms of other countries in a number of areas, including intellectual property, antitrust law, central banking policies, oil & gas ownership by the state, environmental standards, labor standards, tax levels and policy, and so on. It did this mainly by pushing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, now ratified by 38 states, which are required by the Convention to implement FCPA style laws nationally. The UK has confirmed by creating the UK Bribery Act.25

It is important to note that the FCPA does not contain a private right of action. Hence, only the government can enforce the Act. But, private complainants have steadily found creative ways to use FCPA violations as predicated acts in private causes of action. These private actions are often opportunistic in that they usually commence after a government investigation has become public, and they use admissions and settlements in the government context to further their own cause of action.

For example, in 2010, Innospec Inc. pleaded guilty to violating the FCPA by bribing officials in Iraq and Indonesia to ensure sales of its product in those areas. It agreed to pay $14.1 million dollars in penalties and to retain an independent compliance monitor for three years to oversee the imposition of an anti-corruption compliance protocol. On the same day, it also settled a civil complaint with the U.S. SEC requiring it to disgorge $11.2 million in profits.26

After Innospec pleaded guilty, its competitor, NewMarket Corp., brought claims against it for antitrust violations.27 NewMarket claimed that Innospec paid bribes to the Iraqi and Indonesian governments so that those governments would favor Innospec’s product, would not transition to NewMarket’s product, and would therefore maintain Innospec’s monopoly in those markets. Pointedly, NewMarket’s principal financial officer, David Fiorenza, said that it was only after reading about the plea that he learned about Innospec’s actions,28 which would eventually form the basis of NewMarket’s complaint. This case ultimately settled in October 2011 when Innospec agreed to pay NewMarket $45 million.29

The lack of a compliance defense, as shown in Innospec’s case, is particularly problematic in the successor liability context, as a company does not have any defense under the FCPA for the corrupt actions of an acquired company. This is true even if the acquiring company adhered to its compliance program by conducting a rigorous due diligence investigation, but ultimately failing to uncover corrupt acts.

In light of government’s resistance to amend the FCPA and the pace of recent FCPA enforcement, the addition of a corporate willfulness requirement or a compliance program defense is unlikely in the short term. Nor can one expect to see the elimination of successor liability. With this legal environment, companies should focus on effectively implementing a compliance program, while actively looking for opportunities to ensure that other companies (particularly competitors) are not able to reap the benefits of illegal acts.

Preventing Corruption and Crime through Software and Web-Based Analysis

With the rapid development of the Web, cross border investigative processes are literally assaulted and overwhelmed by huge quantities of data. To process and understand these data, due diligence personnel and investigators must make use of software and Web tools. To chart and track potential criminal enterprises, one can use software applications such as Mindjet30 or IBM’s I2.31

While Mindjet is more generic for brainstorming data, I2 provides intelligence analysis, law enforcement, and fraud investigation solutions, delivering flexible capabilities that help combat crime, terrorism, and fraudulent activity. Jay Liebowitz’s book on information analysis, Strategic Intelligence: Business Intelligence, Competitive Intelligence, and Knowledge Management,32 describes I2’s use in cases of major investigations on prescription-drug-diversion fraud and other scenarios. I2, Pajek*, UCInet* and similar software are ultimate tools for cross-border investigative tasks and will provide new value to the due diligence process when trading abroad.

Figure 14.8 The European business registry database unifies registries of commerce from several European countries

Source: EBR

The European Business Registry (EBR) database33 is another very efficient tool for due diligence process in attempting to prevent an investor in dealing with a corrupt organization abroad. The database, depicted in Figure 14.8, has unified data contained in registries of commerce in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Jersey, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, Ukraine, and UK. Name-based searches are possible. Prices differ from country to country and are mentioned with each search.

Another excellent software application is Lexis-Nexis,34 as depicted in Figure 14.9. It requires subscription and payment. Lexis-Nexis is a compilation of databases and offers access to media reports, company registrars in many countries, court cases, financial markets information, people’s searches, and many others. One useful tool inside Lexis-Nexis is the access to the Dun and Bradstreet companies’ database, which covers the whole world. Usually companies involved in imports-exports are listed in this database.

The United States has a wealth of databases, which can be used to track down suspicious corporations. A useful web portal is the National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS) at http://www.nass.org. You will need to register with the portal, free of charge, in order to have access to the registrar of companies of 50 states plus the District of Columbia.

Another good resource is the Global Legal Information Network (GLIN), at http://www.glin.gov, which is a public database of laws, regulations, judicial decisions, and other complementary legal sources contributed by governmental agencies and international organizations. You can find in it data on Paraguay-based companies, published by official publications such as the Gaceta Oficial de la Republica del Paraguay.

Figure 14.9 The LexisNexis database offers access to media reports, company registrars in many countries, court cases, financial markets information, people’s searches and many others

There are many other resources to assist an investor or organization in conducting a sound due diligence regarding a foreign company. These listed here are just a few of the many resources available, which are beyond the scope of this chapter and book.

Conclusion

The support of international agencies in curbing corruption indicates heightened awareness in the public sector and growing concern on the part of governments to put in place structures and programs dealing with this formidable problem. The increasing concern about the dangers of corruption among the emerging markets, often by multinational corporations from advanced economies, and the need for urgent action must be matched by a similar sense of urgency in the G-7 and G-20 summits. In the final analysis, the political will to empower and support those whose task it is to discover, investigate, reveal, and punish corporations in the public sector will be the major determinant of success. Support from these summits could assist in that regard.

In our opinion, the international business community should work more closely with law enforcement to detect patterns and methods of organized crime, since so many crimes fund terrorism. More detailed analysis of the operation of illicit activities around the world would help advance an understanding of wide spread corruption, crime, and terrorist financing. Corruption overseas, which is so often linked to facilitating organized crime and terrorism, should be elevated to a U.S. national security concern with an operational focus. A joint task force composed of analysts from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), as well as Interpol, should be formed to create an integrated system for data collection and analysis. A broader view of today’s terrorist and criminal groups is needed, given that their methods and their motives are often shared.

* Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, Done at Paris, Dec. 18, 1997, 37 I.L.M. The OECD Convention was signed on Nov. 21, 1997 by the twenty-six member countries of the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development and by five non-member countries: Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, and the Slovak Republic.

* NATO is an international organization composed of the United States, Canada, UK, and a number of European countries, established by the North Atlantic Treaty (1949) for purposes of collective security.

* http://www.unicri.it/topics/organized_crime_corruption/

†www.worldbank.org/anticorruption. Last accessed on 10/10/2012

* Designates a type of corporation in countries that mostly employ civil law. Depending on language, it means anonymous society, anonymous company, anonymous partnership, or Share Company, roughly equivalent to public limited company in common law jurisdictions.

* For more information on this theme, see Paolo Mauro, “Corruption and Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 681-712 (1995); Sanjeev Gupta, Hamid Davoodi and Rosa Alonso Terme, “Does Corruption Affect Income Equality and Poverty?” IMF Working Paper 98/76 (Washington, DC: IMF, 1998); Paolo Mauro, “The Effects of Corruption on Growth and Public Expenditure.” Corruption: Concepts and Context, 3rd Edition, Arnold J. Heidenheimer and Michael Johnston, Editors, Transaction Publishers, 2002, New Brunswick, NJ.

* U.S. Department of Justice page on the FCPA, including a layperson’s guide. Download a free copy of it at http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/guide.pdf.

* See FCPA Act See 15 U.S.C. § 78m.

* Commonly referred to as the RICO Act, this is a U.S. federal law that provides for extended criminal penalties and a civil cause of action for acts performed as part of an ongoing criminal organization. The RICO Act focuses specifically on racketeering, and it allows the leaders of a syndicate to be tried for the crimes which they ordered others to do or assisted them, closing a perceived loophole that allowed someone who told a man to, for example, murder, to be exempt from the trial because he did not actually commit the crime personally.

* Kinsella is an American intellectual property lawyer and libertarian legal theorist. His legal works have been published by Oceana Publications, which was acquired in 2005 by Oxford University Press and West/Thomson Reuters

† Mr. Rockwell was also the former editorial assistant to Ludwig von Mises institute. He is the founder and chairman of the Mises Institute, and the executor for the estate of Murray N. Rothbard, and editor of LewRockwell.com.

* Pajek, a Slovene word for Spider, is a program for analysis and visualization of large networks. It is freely available, for noncommercial use, at its download page at http://pajek.imfm.si/doku.php?id=download.

*Ibidem

*Ibidem

‡Ibidem

* UCINET is a software for analyzing social network data.