CHAPTER 8

Delivering the Decision

I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

— Michelangelo

Going through the three pillars of the Quantitative Intuition (QI)™ framework from precision questioning through IWIKs™ and the backward approach to contextual analysis and finally to a synthesis you have triangulated the intuitive and quantitative signals to reveal a decision. It may have been barely hidden or buried deep, but this new “truth” is now known to you. And right there is the final hurdle. The insight and the recommendation, along with its justification, is known to you or perhaps a few colleagues who have taken this data‐driven journey with you. What do you do now to bring along the stakeholders and gain their support?

Reaching a decision can be an accomplishment but taking action on it is the necessary step for the decision to have value. Decisions are often personal but typically involve others at a minimum for awareness and usually engaging stakeholders for cooperation and consent across the organization. This final step of communicating a decision to trigger stakeholder action can be thought of as delivering the decision and if done poorly risks wasting all the preceding effort.

The Story Arc in Decision‐Making

The practice of storytelling is as old as time itself and transcends not only countries and continents but entire historical eras. Humans are one of the few species who tell stories to communicate. It's acknowledged that bees tell stories in some form to their hive to pass on specific details about their wider habitat and how to navigate to pollen sources. Many humans feel their dogs are communicating with them and some even feel the communication is bidirectional. However, humans uniquely use narrative and a story arc, typically with a chronological construct—reaching through the past, present, and projecting the future possibilities—to deliver detailed messages. It helps humans to share their understanding with others, to find meaning in recognizable patterns and to impress important arguments on others in a memorable way. The power of storytelling can hardly be understated, and that's why it's just as important to leverage the power of storytelling in a corporate environment, as it is when trying to get a rambunctious toddler to go to sleep. Our initial messages as cave dwellers were primitive but necessary for survival and helped us form the first tribal communities. Today, storytelling uses layered details, historical perspective, and multimedia forms to create an emotional connection. Storytelling goes beyond entertainment and makes information understandable and memorable.

The story arc reassures the listener by providing a familiar pattern to follow. Joseph Campbell's work on the Hero's Journey1 describes 17 steps in the story arc that can be clustered into three phases. As with a three‐act play, the first act or Departure defines the journey ahead. For the purposes of decision‐making, the first act can be crafted from IWIKs and the definition of the essential question to frame the problem, a process that is explored in Chapters 2 and 3. The second act, which a playwright might think of as the Confrontation or Campbell would call the Initiation, is where the action is explored and we further use interrogation mindset along with guesstimation to put information in context and pressure‐test the assumptions and details. The third act is the Resolution or the Return. Here, we draw conclusions and use our synthesis techniques while triangulating the dimensions and constraints of time, risk, and trust. This is the point at which stakeholders actually reach a decision.

Against the story arc construct, we also recognize personas moving through the stages of decision‐making. The key persona is the Hero who is confronted with a Challenge. In business, the Hero is not often your company but rather your customer. The best advertising reflects that focus on the customer rather than the product or service provider. There are exceptions, usually where a community forms around certain lifestyle brands like Apple or Nike, and the storytelling takes on the tone of attachment to the brand as the Hero.

Typically, the customer Hero then encounters a Change Agent who enables a transformation and the completion of the Challenge. The Change Agent is most often you as the product or service provider. The Hero crosses the Finish Line once the key milestone is achieved with help from the Change Agent. From this, Lessons Learned are revealed that expose fundamental truths about the power of the Change Agent and the Hero's ability to persevere and opportunity to further succeed. If this seems familiar, it is. Most children's stories, as well as many novels and movies follow this structure—introduction, conflict, resolution, and then lessons learned. This simple flow is clear and effective for any storytelling to an audience of any age.

Of course, the realities of human communication and the complexity of the information involved can complicate this straightforward construct. The gap to address in business storytelling begins at the inception of the work. Do we have an agreement on the Challenge or problem to solve in detail? Can we describe it clearly? Does the data support the case? Why are we addressing this now and does it fit with our business strategy? Why is this a priority for our customers and for our stakeholders? Do we as the Change Agent (your company's product or service) have brand permission by the customer Hero to help solve their Challenge? And is this a Challenge we as the Change Agent consciously choose to solve (invest in) and around which we want to build a new revenue stream?

These questions may seem overwhelming but are resolved by methodical application of the techniques we have explored beginning with IWIKs and backward approach to define the essential question and correlation with the customer's North Star and the North Star of our business. Does the audience of stakeholders and influencers agree? Storytelling is the skill set that must take center stage here. What do you recommend the stakeholders and key parties to do? You must make the case for them to care by sharing a clear synthesis of information and intuition, or the decision will be an easy and swift denial to proceed.

Tuning the Narrative

We all tend to think that we are good storytellers. After all, we tell our own stories to ourselves throughout the day. We narrate for ourselves and look back to the conversation we just had or our interactions with others over time. We exercise our storytelling skill constantly and as our own documentarians, our narrative voice is always there, but is it objective? What details does our narrative focus on—the data, the people, the events, the broader theme of a situation?

While a narrative voice most often amplifies bias, it must also incorporate and value an objective view, balancing quantitative and intuitive insights. This divide is where we begin to see others as either “a numbers person” or “a relationship person.” In reality, we are both. Even those who claim to not be comfortable with math will engage in deep conversation about the meaning and the implication of the numbers. In turn, the data scientist could simply convince themselves based on intuition that their numbers are right. In either case, does our self‐evaluation of our storytelling capability match what a listener absorbs?

According to a BBC Future report2 on how geography influences how we think, when asked to name the two related items in a list of words such as “train, bus, track” people in the West might pick “bus” and “train” because they are both types of vehicles. A holistic thinker, in contrast, would say “train” and “track” since they are focusing on the functional relationship between the two—one item is essential for the other's job. Similarly, when a business problem is brought to a range of domain leaders (i.e., finance, marketing, product development), each will draw a different conclusion. They will each interpret the data as they are already inclined to see information. If you are an effective storyteller, this is the opportunity to apply a thoughtful understanding of what your stakeholders will interpret from the story you are about to tell to drive collaboration and consensus across different groups.

Before you get to a room to deliver your synthesis and well‐thought‐out conclusions, it is crucial that you develop a good understanding of your audience, where they are coming from, and what they are looking for. It is also important to be prepared for the different personas you are likely to encounter. Your audience also has a set of archetype personalities for you to navigate. Beyond the Deloitte Business Chemistry personality types (explored in Chapter 7), we see some new friends whom we can refer to as: Billie Numbers who is the data analyst or Data Scientist, Seymour Why who simply has no limit to their requests to “see more data,” the Silver Surfer who is the stakeholder and final decision‐maker, and Chris the Business Case Champion who is your advocate and very tuned to meeting the exact terms of the business case. Each of these characters could reside in any business function—marketing, finance, product development, sales, operations—but their impact is the same. They are gatekeepers protecting their point of view and it is your job to bring them on board.

Each persona plays a unique role in expediting or tormenting a decision.

- Billie Numbers is a spreadsheet and data wizard who must prove value to the senior stakeholder, his boss the Silver Surfer, by driving the interrogation of your presentation and questioning the analytics. There is always another view of the data and another analysis that can be considered regardless of their relevance. Your objective is to prevent Billie Numbers from derailing the conversation from the essential question and toward why you used this three‐letter acronym method for the analysis and not the other method that Billie recently learned about in an academic article. Directing Billie Numbers to the detailed appendix that supplements your deck with the data and analyses will help keep Billie Numbers busy exploring the numbers, while you are focusing on your story arc. If you anticipate several Billie Numbers personas in the audience, you may want to bring with you your data analyst who can rigorously handle the questions from Billie Numbers while you are convincing Silver Surfer on the recommendation. It is also important to let Billie Numbers feel reassured that the detailed data questions he asks are important and that fierce interrogation of data is an important step. After all, Billie is not necessarily trying to find holes in your analysis; he is probably mainly just trying to impress his superiors. To keep on his side, make sure that his questions look good but not risk the integrity of your conclusions.

- Seymour Why is the business line manager who has the limitless endurance to ask “why” and “show me the details” at any and all breaks in the conversation. No business case is safe, and Seymour will continue to ask questions, whether they drive the conversation forward or not, until the buzzer for the end of the meeting sounds and sometimes even after that. To manage Seymour, you need to keep pressing the importance of the essential question and the need to find a solution to the problem. Highlight the distinction between the “what?”, the “so what?”, and the “now what?” and that urgency of moving the discussion forward to from the “what?” to the “so what?” and eventually to the “now what?” To mitigate Seymour's repeated requests to see more data, demonstrate the false value of obtaining ever more data and demonstrate that the new data, even if obtained, is unlikely to change our course of action toward the essence of the recommendation.

- Silver Surfer, our stakeholder, has the attention span of a mosquito and is attached to their iPhone, which they were reluctant to upgrade from their beloved Blackberry. There is a brief moment in the meeting, often early on, where you can get the Silver Surfer's attention and approval, but if that window passes, you are dancing with Billie and Seymour for an hour. Silver Surfer is your key audience. It is crucial that you keep eye contact with Silver Surfer throughout the presentation, particularly as you discuss the main recommendations in the executive summary and elsewhere. Try to assess Silver Surfer's acceptance of the recommendations and probe them directly if needed. Our recommendation in Chapter 6 to make your bottom line your top line as part of your synthesis is particularly important for communicating with Silver Surfer. Don't be discouraged if Silver Surfer is tuning out of the discussion as you get to the nitty‐gritty details of your analysis, but make sure to bring them back to the discussion by gently raising your voice and using cues like “going back to the key recommendation for the firm” as you summarize the main recommendations.

- Chris the Business Case Champion is the Dean of Discipline and wants everyone to win but only if the business case is fully vetted and the case exceeds expectations. Chris is actually your advocate and coach but is also a disciple of process. Make sure that you make Chris look good when presenting your analysis and recommendation. Chris is the one who often brought you in, and your success is dependent on one another.

There may even be other personas or sets of these personas—imagine a squad of five Billies and two Seymours all about to queue the circus music rather than listen to your thoughtful business case. Rather than confronting their interrogation, a storyteller should anticipate what question each character will ask and plan in advance how to either address each question by incorporating the colleague's perspective, neutralize it with appropriate information in the appendix where they can be sent to read, or respectfully park the line of questioning for another time to redirect the group to return to the essential question and move forward to consider the decision. Even the simple recognition of these personas in the meeting would be a big step forward in advancing your communication objective. You should practice a nonlinear transition among the content, and be prepared to manage questions from the different types, while staying focused on your objective.

We could spend many hours debating the manifold reasons why storytelling is so powerful, but we think that it can be condensed down to one simple truth, which is that deciphering meaning is dependent on dimensions beyond the facts. So, what do we mean by this?

Interpretation is complicated by the emotion and even the intonation attached to specific words. Take the following sentence:

“I never said she stole my money.” Consider, for a moment, what you think the overarching message of this statement is.

Now recite the following iterations of the sentence aloud, adding emphasis on the italicized bold word:

-

“I never said she stole my money.”

“I NEVER said she stole my money.”

“I never SAID she stole my money.”

“I never said SHE stole my money.”

“I never said she STOLE my money.”

“I never said she stole MY money.”

“I never said she stole my MONEY.”

-

Instantly—based on the sound of each sentence, pause, and the word that's emphasized—it's clear that the intended meaning of it—the message that it's designed to convey—varies.

In the first example, the implication is that the speaker is not taking issue with the fact that the money was stolen, but rather with the fact that he or she—the “I” in this case—was not the person who accused “her” of that theft. In the second sentence, the implication is that while she might well have stolen the money, the “I” never said as much in spoken words. In the fifth sentence, the emphasis implies that there's an issue with the word stole—perhaps the money was merely borrowed? —while the penultimate phrase seems to imply that the money might not have been mine to start with. The final sentence questions whether the object of the theft really was money at all. Perhaps it was something else entirely.

This example might seem a little simplistic—even whimsical—but psychologists actually use this precise sentence to illustrate that inference really matters: the interplay between the left brain and the right brain is of paramount importance when making decisions, which is perhaps an optimal example of the constant balancing act inherent in Quantitative Intuition. More fundamentally, it illustrates the basic importance of how a story can change a message entirely—revolutionize it, even—depending on how it is told.

Now consider the more realistic and complex situation of delivering a data‐driven decision. Looking at the same set of figures different decision‐makers may draw different conclusions. Furthermore, the skilled storyteller may emphasize different aspects of the data or analysis to help support their recommendation or decision. This is a double‐edged sword as it can be used to support a sound conclusion but also to cherry‐pick the emphasis of certain aspects of the data to promote a decision that supports a particular agenda.

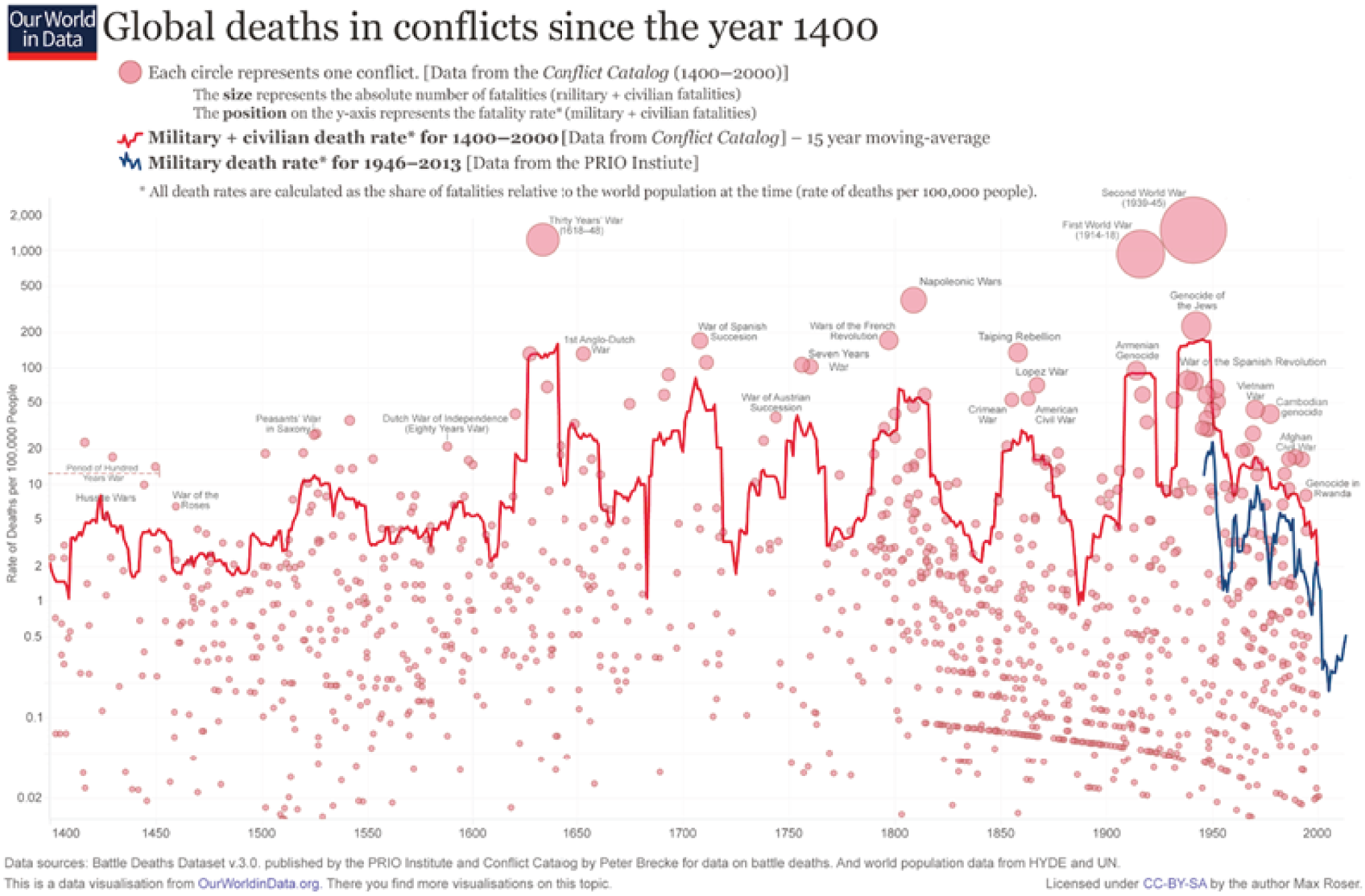

Consider the following image depicting the global death from conflicts (see Figure 8.1) over the past few centuries. Similar to putting the emphasis on different words in a sentence in the preceding example, depending on the point the storyteller wants to emphasize or their inherent level of optimism or pessimism, they may put the emphasis in discussing this figure on the decline in per capita death rates in the past 50+ years, concluding that the world is becoming a safer place. Alternatively, they may emphasize the increased frequency of conflicts in the past century and the increased number of deaths per conflict (the increase in the size of the circles) in the same period, highlighting the increased risk of a conflict with a major number of fatalities. Yet, another presenter may decide to put the focus on what may look like cyclicality in the line graph, highlighting the risk that we may be due for another big conflict. Each of these points of view on the same graph may lead to inherently different conclusions. These different narratives may simply stem from different perspectives taken by the different storytellers. However, in more alarming scenarios, the agenda of the storytellers may guide their point of focus. The fierce interrogator of data would take a broader view of the figure to identify possible alternative narratives.

Despite sophisticated storytelling, we are all surrounded by ambiguity. Whether that's facing challenges with the very meaning of words, the interpretation of a sentence structure or argument, or even the fundamental scope of a concept. Humans often communicate ambiguously, especially via the spoken word so we each tend to feel a compulsion to parse and examine things for exact meaning, often without ever getting close. “We'll do what's right,” is tragically ambiguous yet implies comfort and best intentions. “The right thing,” is bandied around as a phrase, but never truly defined. Are we referring to the Rule of Law or the Golden Rule? Even in the Hippocratic Oath, can we ever really be entirely sure what “do no harm” actually means?

Further, all listeners, including the different personas we outlined earlier, are not equivalent and may interpret the same information differently. If a seemingly simple sentence can easily be interpreted in multiple ways, the messenger who delivers complex details for a decision to be made is best served simplifying the message and considering how that information is received by each individual stakeholder. If you are one of a group asked to silently name a flower, you will name the flower that first comes to mind, as will everyone else in the same discussion. Now you have a mixed garden across the listening audience when, in fact, the storyteller may have had a specific flower in mind as a key point of the story. So, if a simple element of a story can be interpreted in multiple ways, consider how a group will evaluate a sales spreadsheet, a financial report, or a medical chart. Much like the task “name a flower” would generate multiple results, an unguided review of a spreadsheet will lead to multiple perspectives and wasted effort addressing less relevant topics that become distractions within the reviewing team.

FIGURE 8.1 Global deaths in conflicts since the year 1400

The storyteller can control the focus of the discussion by highlighting the truly critical points at several levels of communication. At the outset, as is recommended in Chapter 6, the top line must highlight the bottom‐line value of the decision. In journalism this is referred to as “not burying the lead” so as to ensure the primary message or recommendation is clear and is driving the discussion.

Focus on critical elements for consideration in the discussion can also be achieved by amplifying details and examples that support the primary decision to be made. The critical elements are obvious in advertising and marketing communication, but less so when data is incorporated. The advertiser is explicit and has mastery of quickly highlighting issues and attributes. The specific flower—a rose—is called out. Brands lead with “sparklers” that are efficient to absorb, easy to understand, and memorable for the audience. Sparklers offer comparison and context (i.e., “our product is 50% faster, cheaper, better”) and often reflect current issues (i.e., “locally sourced from 100% recyclable material” or “Our mission is to make all of our products sustainably by 2030”).

We see this every quarter on Wall Street where a company having a successful quarter leads with its financial outcomes. Its progress and success is obvious from the data and easily presented. Meanwhile, companies disclosing less than stellar results or nuanced progress against long‐term goals begin with a narrative to position their results and circumstances in a favorable light. Under then‐Chairman Sam Palmisano, IBM committed to increase earnings per share from $6 in 2006 to $10 in 2010 and then double that by 2015. The reliability of the progress and the narrative of financial discipline was attractive to Wall Street, but the storytelling bypassed the challenges it created by diverting funding away from people, products, and future investments.

The effectiveness of the messaging is also related to how the listener is engaged by the use of facts and data, emotions in storytelling, and memorable symbols that reinforce the storyline. Voice Lessons by Ron Crossland and The Leader's Voice by Boyd Clarke and Ron Crossland address the brain science of engagement and retention. In their work, we see the advantage of utilizing all three—facts (highlighting the quantitative data analysis), emotions (incorporating intuitive analysis), and symbols.

Stories that trigger a particularly strong emotional response from the audience are likely to be the most effective in the sense that they'll be memorable and easy to recall.

The value of symbols in storytelling brings an additional layer to the communication. Broadly speaking, a symbol can be defined as something visible that stands for, or suggests, something else, by either relationship, association, convention, or even accidental resemblance.

Symbols can be extremely simple but have complex and even controversial associations that are extensive. Take the mathematical symbol for the number pi for example: ![]() .

.

Some might understand this to simply be a visual representation of a number that can be rounded up to 3.14159 and denotes the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter, but others would disagree vehemently. Entire books have been written about how pi also represents society emerging from the Dark Ages and the ensuing conflict between mysticism and science.

Take other examples. A simple image of a lion might evoke the ideas of courage, bravery, and strength, or it might remind you of a brand or company. Other animals will conjure other concepts and ideas that will be different for different people or cultures. The peace sign will be interpreted differently depending on the era and who the viewer is, as will the yin and yang symbol. The peace sign has evolved over the course of five decades from peace to protest against wars to inclusion when it is in a rainbow pattern. A picture of a set of weight scales might relate to buying and selling farm produce for one person but for the majority of people around the world it is the image that best sums up the notion of justice or the legal profession.

In their simplicity, symbols are extremely powerful in that they are memorable, evocative and can often convey information in a far quicker and more succinct way than digits and letters might.

Simply recalling Budweiser's Clydesdale horses reverently pulling an empty wagon and bowing in front of the U.S. flag in a 20th anniversary commemoration of September 11, 2001, evokes a flood of emotion. The Clydesdale becomes a symbol of reverence and respect that reflects the brand value that Budweiser wants to be associated with in the mind of the consumer.

Symbols can also be created in the moment. Showing a personal item such as a pen and telling a story about it or its relevance as a family heirloom can become a memorable touchstone. Meme as coined by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene3 was defined as “ideas that replicate and spread from one mind to the next and now rush through social consciousness given the reach of the internet.” Many of the enduring online memes become symbols at a national or even global level. An internet search for “one does not simply,” “distracted boyfriend,” or “condescending Willy Wonka” reveal thousands of interpretations of those relatable memes as symbols.

We can easily be swayed by a compelling image, so the underlying information must provide a balanced view. An extreme example is the “irrational exuberance” described by former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan to address the wave of optimism leading to the early 1990s internet bubble. At the time, reputable journalists would repeat and amplify the promise of “20X future earnings” in a few years for a startup that had yet to ship the breakthrough product it promised. The journalists on morning financial news programs would highlight the potential of certain startups with no meaningful underlying facts supporting a chart showing wild growth that then drove stock prices higher. Their tone was often infused with surprise and the subtle suggestion to join the party, which preyed on “fear of missing out” by the investor. This is dangerous storytelling, but highlights the power of persuasion and emotional engagement. It also speaks to human nature as this exuberance is repeated throughout history from the Tulip Mania during the Dutch Golden Age (1634–1637) to the 1990s internet bubble to the latest run on Wall Street.

Inform versus Compel

When communicating, there is an implied decision before the discussion begins. Are you seeking to inform others or compel action? While this may seem simple, preparing your audience and stakeholders to make a decision at your next meeting is a completely different task than informing stakeholders or a broader audience about insights and progress. Quite often discussions are not oriented toward either informing or compelling but rather disintegrate into group debate that could be interpreted as decision‐making but is not. While there can be value in the open‐ended discussion, time must be managed effectively when driving a decision in order to meet deadlines and move the decision forward.

Informing stakeholders requires clearly conveying information for awareness and understanding, while setting the context that their actual vote on the decision will be at a later date. The presenter or project lead is bringing the stakeholders along so as to build familiarity over time, accept feedback on interim course corrections, and avoid surprise when the decision must ultimately be made. In fast‐paced businesses, leaders will state they only want to meet to discuss detailed specifics of where they need to take action and do not need to make the time for awareness discussions. However, continuing a project is in itself an action as it translates into ongoing consumption of resources. The feedback or interim course corrections that surface during inform meetings are valuable steps that if skipped can be costly later if projects falter or deviate from the desired path without leadership input.

Communication designed to “compel” decision‐making is organized across both quantitative and intuitive dimensions to shape an immediate final decision. The decision can be stand‐alone or one in a series of stage gates as part of a larger decision. In either case, the stakeholder should be clearly requested to vote and support the position brought forward by the project lead. If orchestrated properly, the ask for action is not a surprise to the stakeholders. Decisions and discussions are typically most difficult when the decision is to make an investment. Compelling a stakeholder to invest budget, resources, and their own personal time further can be incredibly difficult if the case is not clear. Most organizations have defined criteria and thresholds for return on investment (ROI), but the actual decision moment itself is often vague or determined after the presentation asking for the funding support. In the lead‐up to compel a common question is likely to be were IWIKs addressed? Is it clear the recommended action addresses the essential question initially defined? Have surprises been surfaced along with business benefits? Are important consequences considered? and, can the decision‐maker clearly see the “so what?” and “now what?” so as to quickly move to action?

It is incumbent on the presenter or business case owner to drive the clarity through a decision process, including through interim information dissemination meeting and through the final compel meeting where action is requested. The success in driving a decision, then, requires a solid understanding of your audience and how each of them interpret information. This begins with segmenting your audience into the stakeholders, influencers, and distractors, while understanding the fundamentals of storytelling and how to construct a story arc that will ensure action is taken.

Key Learnings ‐ Chapter 8

Success in driving a decision can be improved with focus on the stakeholder audience and focus on the essential problem to be solved. An effective method is to build a presentation brief for planning purposes:

- Know your audience. Identify project stakeholders, their expectations, and their relationship to each other. Recognize the difference between the true stakeholders and strong influencers.

- Consider how your analysis and insights will be received. Ensure the right level of validated information and memorable details are included to highlight the value and impact of the recommendation.

- Understand immediate and long‐term issues and sensitivities. What is the sentiment of the stakeholders and has that changed? Why is this a priority now?

- Deliver a coherent, compelling story with synthesized information that brings forward new insights rather than simply summarizing data. Use data wisely and edit ruthlessly. Don't bury the lead.

- Make your recommendation actionable and clear in an explicit ask that leads to a specific decision with supported outcomes.

Notes

- 1. Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 3rd Edition. New World Library, 2008 (originally published in 1949).

- 2. Robson, David. “How East and West Think in Profoundly Different Ways.” BBC Future, January 19, 2017. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170118-how-east-and-west-think-in-profoundly-different-ways.

- 3. Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene, 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, October 25, 1990.