CHAPTER 9

Chasing the Decision

People will not resist decisions they believe are in their best interests.

— Unknown

Do you often feel like you are running all out, but failing to reach the finish line? You bring your full self, but at the end of the week you are exhausted and your to‐do list is longer. You're overscheduled for next week, and last week's decisions are still pending. You feel like you are constantly chasing the decision. At some point, a colleague usually says, “Well, making a decision like this is a marathon not a sprint.” Frankly, we've never taken comfort in that cliché. Both types of races are challenging in their own right. One is about endurance; the other is about a short burst or maximum speed, and both require commitment to tough training to get in shape mentally and physically. Challenging as both races are, however, they both are only about running, and decision‐making is not a single‐sport challenge.

Decision‐making is more like a triathlon, a multidisciplinary event. Triathlons always start with swimming, followed by cycling and, finally, a run. The swim is first because water poses the greatest threat to a tired athlete—exhaustion could result in drowning. Similarly, the risk from fatigue or error in biking is much higher than in running. Watch the Tour de France, or any competitive bike race, and you'll see a tight pack of riders—a peloton (from the French word for platoon)—moving as a unit. Each rider conserves energy by “drafting” behind others, but any one rider's single mistake can send the others braking, flailing, and scrambling. Last, you have the run, and its challenge is sheer speed and endurance, keeping the legs strong and the mind focused till you cross the finish line.

To be an effective decision‐maker you need to be a triathlete, calling on different abilities and resources for the different events. The discovery phase of decision‐making, like swimming, can leave us drowning—not in water but in data. Analysis, like biking, demands precision and coordination, with your team working together for greater power and efficiency. Last, the discussion phase is like running. It's the final event. You have to battle exhaustion (your own and the team's) and keep your mind and your energy focused on the finish line.

In our work with companies of all sizes, we've studied the problem of chasing the decision. Our research with 2,100 professionals concluded that data in high doses is harmful. It doesn't speed decision‐making, improve logic, or enable the smartest decision. In fact, our evidence shows that while data is black and white, the truth is gray. The gray comes from intangibles such as bias, risk appetite, history, stakeholders' conflicting priorities, problem definition, and expectations. Things we can't know through numbers, but only through insight and intuition, which are both aligned with trust.

We've seen it arise from combinations of the following factors: expectation that senior leadership needs to make the decision, too many voices in the room, not the right people, an absence of or weakness in decision rights, multiple claims on decision rights, competing priorities, excessive permission seeking, lack of clarity on what is being decided, misalignment on the definition of the problem, incomplete information, lack of trust in the data or whoever is delivering, new analysis, and resistance to change. While these are real issues, they are also all symptoms of a larger issue: fear.

We are afraid of casting a decision that's not right, not smart, or making a choice that's not perfect. We fear that if we make an imperfect decision, it will impact our personal brand, our performance rating, our next project, or job opportunity. So, we seek the perfect decision. This quest is counterproductive to agile decision‐making, yet we deceive ourselves, hoping to attain certainty. As we request more information, one more spreadsheet, additional data, streams of data, we end up with countless meetings. Too frequently, we find ourselves spinning. The discussion becomes a debate and drags on, sapping our vitality. And so, we prolong the process, seeking more data. We make slow decisions, misguided decisions, and—sometimes—no decisions.

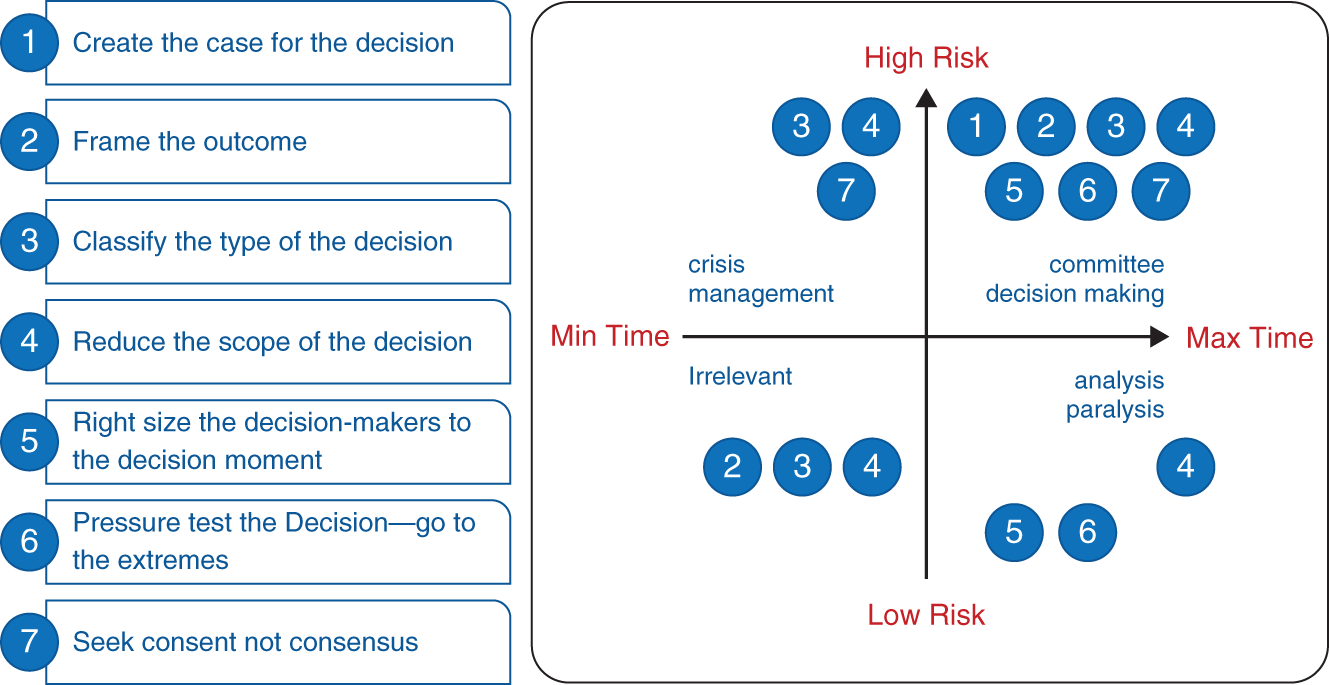

This chapter provides seven practical strategies to help you stop chasing the decision. It is a synthesis of many of the strategies and techniques we discuss throughout the book. To make effective decisions across teams of different size, different types of decisions, and with varying amounts of data, we developed seven lessons to better faster decisions.

Before we look at each of these strategies, we want to emphasize they do not have to be applied in order. It is not a waterfall approach but more like jazz. Depending on your situation, these techniques have been designed to enable you to jump around. You may apply Strategy No. 6 and then jump to No. 4, and back to No. 7. Figure 9.1 shows the seven strategies covered in this chapter.

To fully understand each strategy, you need to look at its underlying principle, show it in action through an example, and then offer tips on why, when, and how you can immediately apply the strategy.

FIGURE 9.1 Seven strategies for making faster and better decisions

Source: Frank, Christopher, Paul Magnone, and Oded Netzer. Decisions Over Decimals, 1st ed. J.W. Wiley, October 2022. Quantitative IntuitionTM.

Strategy 1: Create the Case for the Decision

A decision represents a change—a moment in time when you are asked to consider a different path. Humans are not wired for change, and we think it's important to grasp this: organizations do not resist change—people do. Human resistance weighs heavily on the decision‐making process. Therefore, you need to create the case for the decision in a way that resonates with individual stakeholders, to navigate and overcome people's natural resistance for change.1

Management literature offers an extensive array of change models, and in our work and our teaching, we have considered many of the top models, including Lewin's change management model, the McKinsey 7‐S framework, Kotter's 8‐Step Process, the ADKAR (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement) model, Nudge theory, the Bridges Transition Model, the Kübler‐Ross Change Curve model, and the Satir Change Model. For our purposes in creating the case for the decision, we prefer the Bechard and Harris model. Devised by management consultant David Gleicher and further refined by Richard Beckhard and Reuben T. Harris, the model is brilliantly simple to apply, easily scalable to different sized organizations, and appropriate for many leadership styles, and varying sizes and types of decisions.

The Beckhard and Harris Model2 considers four factors necessary for change to take place: dissatisfaction, vision, first steps, and resistance.3 The first three factors must be sufficiently strong if resistance is to be overcome. Let's unpack each and then discuss how turning these dials will improve decision‐making.

Dissatisfaction (D)

Dissatisfaction with the current state is core for a decision to occur as the pain of not changing must be greater than the uncertainty that comes with change. The level of dissatisfaction can vary from acknowledgment to acceptance to fully embracing the need to move to something different. At a minimum, there must be an acknowledgment of the need to change. The people who will be impacted must be motivated to make the change; therefore, it is imperative to make it clear why the current state needs to change.

Vision (V)

There needs to be a clear and shared picture of the future. The vision creates an image of the ideal state when the decision is made. This is a core part of effective decision‐making as it connects with people on an emotional level. As discussed in Chapter 8, emotions have a 2–3× greater impact on decisions than rational features and benefits. Emotions matter as they not only govern the nature of a decision but the speed of the decision. A clearly articulated vision should evoke emotions such as security, comfort, aspiration, inspiration, or a sense of control. Keep in mind that anxiety is a natural part of any decision as change represents an unknown, but that anxiety is short‐term if the emotional payoff of the future state is positive.

First steps (F)

The first practical step to achieve the vision can seem unattainable by the broader team, so it needs to be broken down into smaller work streams, projects, decisions, or initiatives. Individuals must see how the vision is attainable and, more importantly, understand the specific role they will play in making the vision a reality. The initial steps must be clear and easy to generate high engagement.

Resistance (R)

As discussed earlier, Resistance is always a factor of change.4 People are not wired for change, so resistance must be overcome for a decision to be successful. To overcome resistance, it's crucial to understand the main reasons why people resist change:

- Fear of the unknown

- Lack of understanding of the need for change

- Fear of losing status, security, belonging, or competence

- Emotional connection to the current state

- Lack of trust in those promoting or driving the change

- Insufficient knowledge about the proposed change and its implications

- Lack of belief that change will lead to a better state

These conditions give rise to a change formula:

D × V × F > R

The three components on the left must be present in sufficient quantity to overcome the inherent, natural resistance to change. This algorithm will not yield a mathematical result, but it serves as a guide to creating a meaningful and efficient decision‐making process.

Applying This Step

In creating the case and reasserting it at key moments in any process, as the leader, you want to observe if any of the three factors are present in the decision process and at what levels. Start by doing a quick self‐assessment to see if you are overdelivering on one of these three. Are you anchored in diagnosing the current state? Have you spent too much time getting the team excited by the vision? Is your comfort zone in the details and workplan?

Similarly, you can do a quick check‐in with your team by asking three questions:

- Is it clearly agreed why this issue must be addressed now?

- Is the outcome superior and distinct compared to the current situation?

- Does everyone understand your role and the impact this change could have on you?

Are all three factors present? If the answer to any of these questions indicates that all three factors of dissatisfaction, vision, and first steps are not present, you can easily course correct. Keep in mind these questions are not limited to the start of a project, but should be used to periodically check in. As you get into analysis, production, or various work streams, people may lose sight of the vision or get caught up in the details. Regularly reinforcing why you are working toward a decision will overcome any natural resistance that could surface.

Are you over indexing on any of the three factors? It's important to understand the dangers of neglecting or over indexing on any one factor. A common mistake we observed is that leaders tend to over indexes on one of the elements on the left, ignoring the other two. This may unintentionally be driven by the leader's personal style, the company culture, or environmental conditions such as crisis management or time pressures.

What Does Over Indexing on Dissatisfaction (D) Look Like?

Leaders, teams, or individuals who focus on what is broken, are pessimistic, or are highly critical regardless of the proposed solution. They have a difficult time seeing past the current situation. This intense focus on what is not working leads to frustration or cynicism, serving as a headwind to decision‐making. While it is important to have a realistic view of the current state of affairs, intensely focusing on what is wrong is analogous to wearing earplugs and blinders. You cannot see or hear anything else clearly.

What Does Over Indexing on Vision (V) Look Like?

Some leaders are great visionaries. They thrive in articulating what the future will look like. They do not focus much on dissatisfaction (D) as it may be perceived as looking in the rearview mirror, assuming the pain with the current state is well understood. Any first steps (F), to this type of leader, might feel too process‐oriented and weighted down. These leaders tend to overlook the fact that dissatisfaction (D) is a necessary motivator for others to accept change, and first steps (F) are a means of communicating how the vision can be attained and clarifying everyone's roles. Visionaries see three steps ahead, and the future is bright, exciting, and inspiring for them. They are pioneers. They challenge the status quo. They are creative thinkers, seeing around corners, and pushing to innovate, constantly looking ahead, and putting forward an ambitious agenda. They do this either because ambition is innate or they feel it would be motivating to the team. Visionary leaders are essential. The best visionary leaders can harness dissatisfaction and build a team that excels at process and operations.

What Does Over Indexing on First (F) Steps Look Like?

There is an overreliance on work streams, assignments, and steps. The majority of the discussion is on process, with a focus on the near term. These types of leaders aim for efficiency and feel they are being “buttoned‐up.” They strive toward ensuring they do not waste time, the job to be done is clear and the role and responsibility are laid out, and no time is wasted. There is minimal connection or discussion to the outcome. Similar to a macro camera lens, the focus is extremely close to a subject so that is all that appears in the viewfinder. That is all the team can see. When a step does not go as planned, the work comes to a halt as subsequent steps are dependent on the execution of the previous step. At best, if everything progresses without a hiccup, the intense focus on the first steps means that once they are complete, the team has to stop to regroup and outline the next steps. This impacts agility and nimbleness. Over indexing on first steps also runs the risk of de‐energizing the team because its connection to the vision is missing.

The three factors are like any kind of competency: when it is overdone, it can turn into a negative. Too much of a good thing can be harmful or excessive as the quality of something is relative to its quantity. This is true in the decision‐making process given that you need to overcome people's natural resistance to change. To hasten the decision timing, all three factors must be present to effectively create the case for the decision to make sure your colleagues engage in a productive way.

Strategy 2: Frame the Outcome

Absolute clarity on the outcome is foundational to effective decision‐making. The challenge occurs when there are varying definitions of what success looks like. Your business partner may only need a simple answer, a quick analysis or one number as the speed of the decision is what is most important. In your effort to overdeliver, you generated a pivot table, supported by a set of slides, and wrote a synthesis of your analysis. While it is a robust answer, you actually underperformed, causing delays. If you took the time up front to frame what was needed as is suggested in Chapters 2 and 3, you would have invested less time and had greater success.

A frame is a guide. It shows where to focus by highlighting particular aspects and eliminating others. Framing provides boundaries to help interpret what you see, while being clear on what you need to deliver and guiding how you spend your time. Most teams or clients have little trouble articulating what they don't want. They easily discuss wide‐ranging pain points, but struggle with clearly defining where they want to go. If you show a panoramic picture to a group, the group members will focus on different aspects while all viewing the same picture. They will wind up with a wide range of interpretations of the same photo.

When discussing an outcome of a project, there are typically two extreme scenarios. First, the goal is very clear to the leader. The leader inherently understands what success looks like as they played a significant role in shaping the project. The second scenario is the leader has a vague notion of the final deliverable as they have not invested the time thinking through the outcome or have been asked to take on an assignment without the full context. These polar opposite scenarios lead to the same situation—a vague description of the goal where minimal time is spent discussing what success looks like. Too often in decision‐making disparate views on what is needed are at the root of the endless race to make a decision as people work toward different standards. The team mistakes action for outcomes, failing to ensure it has a common definition of winning. Once a decision is made, it misses the mark or a larger opportunity is missed.

Therefore, it is imperative to define what success looks like and then educate and evangelize the outcome. In military scenarios, there is a concept called victory conditions—conditions by which one wins. The successful leader clearly outlines what is needed to move forward. They break down a complex campaign to the essence, using the simplest terms, thereby ensuring clarity so the entire unit works as one to move forward.

Applying This Step

The concept of victory conditions can be applied to any team environment, whether it be a school project, volunteer group, or workplace. It is as simple as asking:

- What does winning look like?

- Do you need a gold, silver, or bronze solution?

- What is the essential piece of information you need to make a decision?

Going back to our panoramic picture, think of the victory condition conversation as a technique to crop the picture to remove the unwanted outer areas. Understanding what success looks like helps you to frame the picture. It focuses the team on the data that is needed, what analysis is required, and the decision(s) that are required (see the Working Backward approach in Chapter 3). Pausing to have this conversation ensures the effort reflects the need. We frequently use the expression “Don't build a rocket ship when a bicycle can get you there.” Don't create more complexity than is needed.

According to the Merriam‐Webster Dictionary, overengineering is the act of designing a product or providing a solution to a problem in an elaborate or complicated manner, where a simpler solution can be demonstrated to exist with the same efficiency and effectiveness as that of the original design (see Figure 9.2).

FIGURE 9.2 Overengineering

Image Source: https://hackernoon.com/how-to-accept-over-engineering-for-what-it-really-is-6fca9a919263.

In decision‐making, the goal is to match the need with the appropriate outcomes. Overengineering the decision wastes resources and depletes energy. Overengineering a decision can be draining to the team, as it is often tasked to solve tertiary problems in addition to the primary objective. There is also a downstream effect as it dilutes the team's focus from working on other projects. Clarity on the outcome will foster speed of decision and have a positive halo to other aspects of the business.

Strategy 3: Classify the Type of Decision

Humans do not want to fail. While this is an aspirational goal, it inhibits agile decision‐making. This fear of failing is tied to the feeling that once a decision is made it is not reversible. With this in mind, Amazon approaches the decision‐making process by categorizing decisions as Type 1 or Type 2. In a shareholder letter, Jeff Bezos discussed this decision‐making mindset.5

- Type 1 Decisions: Almost impossible to reverse. Think of decisions as doors. A Type 1 decision is a door that only permits passage in one direction. Since Type 1 decisions are difficult to reverse, they are heavyweight decisions that will take a great effort to undo, such as deciding to open a manufacturing facility, shutting down a product line, or entering into a merger.

- Type 2 Decisions: Easy to reverse. These decisions are doors that permit two‐way traffic. The majority of decisions are Type 2 and can be reversed.

Chapter 7 discusses how the reversibility of the decision relates to the assessment of the risk dimension of the decision at the decision moment.

Applying This Step

While this is a useful taxonomy to bucket decisions, how do you actually classify a decision as reversible or not?

When faced with a decision, consider how easily you could modify the decision. What will it take to change the decision once it is made? Consider if there is some point when it becomes irreversible. Is this a lightweight decision that is reversible or a heavyweight decision that is irreversible?

You will often find that the majority of decisions are reversible. If you find that many of the decisions are falling into the irreversible category, reduce the scope of the decision, which is the subject of the next strategy.

Strategy 4: Reduce the Scope of the Decision

The larger the decision is, the greater its impact. In our quest to make a fast decision we often strive to move from point A to B. In early childhood we were taught that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. That knowledge is based on the work of Archimedes of Syracuse.

Not wanting to challenge a notable Greek philosopher, but mathematicians, rightly so, have countered this argument. Basic geometry shows the shortest distance between points A and B depends on the underlying geometry. If the landscape is perfectly flat, then a straight line represents the shortest distance. In decision‐making, much like in nature, the landscape is rarely flat and unencumbered.

Big decisions typically involve a broad set of stakeholders, more inputs to consider, or the need to optimize for multiple outcomes. The decision landscape is therefore “curved.” In addition to the landscape, as we have shared throughout this book, there are many headwinds that could shift your plan, much like in sailing.

If you have ever sailed or observed sailing competitions, the destination is established but the journey is never a straight line. The longitudinal and latitudinal coordinates are known, but on any given day there are ancillary factors such as wind speed, tides, obstacles, crew skill, and weather that the skipper at the helm must navigate. No sailboat can sail directly straight as the wind coming head‐on would flow around the boat preventing the sails from filling. However, by harnessing the forces created by air and water and constantly making adjustments to capture the wind, the boat moves rapidly forward. These adjustments are a sailing maneuver called tacking. Tacking looks like a series of sawtooth movements that take advantage of the wind while moving closer to the destination. Regularly assessing the wind leads to minor refinements, ensuring the boat remains on a favorable tack. Though these periodic adjustments may add distance, the result is a faster trip with less wasted effort.

Applying This Step

The experienced decision‐maker applies the concept of tacking (see Figure 9.3) by breaking the larger decision into smaller steps. The focus is on resolving these micro‐decisions to demonstrate progress and enable real‐time adjustments to the headwinds. These headwinds could be new data, change of priorities, shifting timelines, or competitor actions. The headwinds represent factors that must be navigated to make a decision. By working on bite‐size decisions, the impact of these headwinds is minimal as the redirections are smaller and the change to the overall decision is smaller.

To become a skilled decision‐maker, avoid mapping a direct path from A to B, but instead break down the overall decision into micro‐decisions that require less time and/or have lower risk. You then assess the headwinds and gauge impact on the micro‐decision. If the headwinds are constant and your work streams are moving forward, you are on a favorable tack. Keep going. If you determine you need to reverse direction or course correct it is much easier. This is a fundamental change in the decision‐making approach. Micro‐decisions need fewer people, require less effort, and limited inputs. Your ability to veer off course is contained. By reducing the scope of the decision, the speed of decision‐making increases as people have the confidence to make a small decision as the risk of failure is reduced.

FIGURE 9.3 Decision‐making via tacking

A key part of this technique is to regularly assess progress and communicate to the team. Communication is essential to link and label the small decisions to the larger goal as the small decisions may not be perceived as a forward motion. Recall that a person's natural inclination is to reach the destination. Their definition of success is black and white—did we achieve the goal or not. Through frequent communication, you reinforce that you have not lost sight of the goal and all the tasks are moving toward accomplishing the objective. The communications should be open and transparent. Even when you need to redirect and change course, this should be discussed. By bringing along the team and putting the changes in context of the larger goal, team members will see how they are in service of achieving the overall outcome.

Strategy 5: Right Size the Decision

If you've ever watched young kids play soccer, it is like watching bees flying from one flower to the next. The whistle blows, the ball is kicked, and the kids fly off chasing the ball. The parents start yelling with verve and vigor. The coach brings fantastic energy encouraging the team. With so much going on, you lose sight of the ball. Then a flicker of the ball is seen. The group pauses, disbands, and then starts running all out. Everyone is aiming for the ball. Kids are running. Parents are jumping up and down. The coach is hooting and hollering. The energy is contagious. For 50 minutes this goes on.

The goal is clear. Literally, there is a goal. The objective is well understood: get the ball into the net. There is encouragement, perseverance, and high energy. There are adults with different levels of experience, skills, and knowledge. Yet we all know how the game ends. Everyone is exhausted from running all out, the score is usually a tie, and there is a treat for all the effort.

As the kids grow older and coaching becomes more seasoned, the shape of the game changes. The games become more competitive. A few teams break out and make it to tournaments, division events, or playoffs. They gain skills through learning valuable lessons about passing and assisting, and they learn to play to their positions. They substitute players based on the competitor, score, and skill set. The energy matches the moment. Sometimes they win; other times they lose, but they are competitive. The games move fast. Whether you play a sport or enjoy watching it, you've observed these types of games.

These are valuable work lessons that enable faster decision‐making. When a new project is launched, team members pounce on the ball with positive intent. Additional colleagues are brought in. As the decision looms, the number of voices in and outside the room increases. Activity is often confused with outcomes as people are jumping from one meeting to the next, emails are flying, slides are being developed, data is being pulled, and conversations are occurring. At the end, people are fatigued, and there may be a good decision, a poor decision, or no decision at all.

Applying This Step

The goal is to avoid chasing soccer balls. The tendency is to jump in, assemble a team, and start working. All decisions are not created equally. When we stop to consider this, it is obvious, but teams do not operate accordingly. Often all decisions are treated with the same level of intensity. In reality, different decisions require different skills, people, and timing. The following steps detail a reimagined approach to right sizing the decision‐maker to the decision moment.

- Classify the Decision: Consider the two factors that are discussed in Chapter 7: time and risk.

- High Risk/Minimal Time = Crisis decision situation. Finite number of people.

- High Risk/Maximum Time = Committee decision situation. Larger team.

- Low Risk/Minimal Time = Irrelevant decision. Limited to no or one person.

- Low Risk/Maximum Time = Highly analyzed decision. Targeted team of people.

Figure 9.4 illustrates the following formula:

Less space = Less time = Less People = Quicker decisions

FIGURE 9.4 Decision situational quadrant

- Assess Skill: When a new initiative presents itself, start by outlining what expertise or experiences are essential to making the decision, independent of specific people. Essentiality is a key consideration as you are trying to assemble the smallest, high‐caliber team needed to be effective.

- Identify People: While the reality is you need to consider people's bandwidth and availability, what often happens is you have too many people or you do not have the right people. When you do not have the right people, the risk is you bring in more people thinking the volume will close the skill gap.

- Choose a Leader: Selecting the right leader needs to be considered after you complete steps 1, 2, and 3 If you have a high‐performing team with the right expertise, then you may want a leader with strong organizational skills. If you have a large, inexperienced team with skills gaps, assign a seasoned leader with direct or related experience to the decision. A strong leader can close the gap. If this leader does not excel at planning, be sure to designate team members who can lead the operations.

- Assign Roles: At the project launch, it is important everyone is aware of the goal, but clearly defining each person's role relative to the goal will save a lot of effort. The team leader needs to go beyond simply assigning a responsibility to a colleague and should invest in defining what success looks like and share personal expectations. Ask team members to play it back to you in their own words so they are clear on their position and what they need to deliver. As in sports, “playing to your position” makes it easier to have clear structure and an orderly process, making it easier to complete a task. Each person will be able to deliver at a high level as well as to make course corrections easier while making the translation of effort toward the goal with a high degree of success.

Many companies make fast decisions in a crisis situation. They may not make the perfect decision, but they make decisions quickly. There are some lessons to extrapolate from crisis decision‐making. Less time and higher risk creates a tight space at a fast pace. Team members quickly focus to adapt to a fast pace. Creating small teams with short timelines focuses their effort on improving nimbleness.

Strategy 6: Pressure Test the Decision—Go to the Extremes

It is essential to know the strengths and weaknesses of a decision so that you can prepare accordingly. The concept is analogous to that of pushing a solution or a product to its limits—a common and best practice in engineering. The objective is to measure, in a controlled environment, the maximum stress that a material can withstand before breaking. This guides the manufacturer on product design, usage, and features to optimize performance and avoid failure. It occurs across industries from automobiles, appliances, tools, and toys to software, websites, and mobile applications. The tests are known by various names such as stress testing, load bearing, or line testing, but they all refer to understanding the limits of the design.

When applied to evaluating management strategies it is called war gaming where elaborate simulations mimic competitors, trends, technologies, customer needs, and market dynamics. During a single day or over a series of days, various models are run to provide different views. Variables are adjusted, teams role play competitors, and a range of potential responses are enacted. At the conclusion, the company has a deeper appreciation of the points of superiority, inferiority, and gaps in the strategy. War gaming is a powerful tool, but it demands a fair bit of time and effort. Since its value is proportional to the effort invested, it is only done infrequently, typically being reserved for major initiatives or long‐term strategic planning.

The reality is the majority of decisions occur on a daily basis. It is estimated the average American makes make 70 decisions per day, according to Sheena S. Iyengar,6 Professor of Business in the Management Department at Columbia Business School. Given the number of decisions that happen frequently the real need is for a technique to quickly expose unidentified risks and to uncover potential opportunities. Any tool would have to be simple, scalable, and fast.

To meet these parameters, we started by deconstructing various testing techniques when a common trait became obvious. Many of the approaches to stress testing systems are designed to look at performance over many points and a broad spectrum of conditions. They cast a wide net to capture performance during a simulated life cycle. However, daily decisions do not require that level of rigor. The techniques that are discussed in Chapter 4 posit that if you consider how a decision will perform at the extreme scenarios, you would be able to quickly assess the viability of the decision, while validating the underlying evidence supporting the recommendation.

But first, let's discuss what we mean by extreme scenarios. An extreme scenario is when you understand a decision/solution/recommendation at their limits. In the auto industry, engineers test the maximum car engine speed that an internal combustion engine is designed to operate without causing damage to any internal components.

In decision‐making, these extremes can be defined by the following examples:

- If you were given 2× more budget than you are asking for, what would you do?

- What would success look like from a pilot program?

- Who will you hear from if you stop this program?

These three examples illustrate how to quickly apply the concept of stress testing to daily decisions. Each case represents an extreme point, the end point, where you would need to provide a response. This does not mean you would get double the funding or that a program would be shut down, but lack of a well thought‐out answer highlights a gap in thinking and analysis. It is a simple way to evaluate if the logic to arrive at the decision is comprehensive.

This tool is particularly effective during budget planning. We have seen the application of this many times in large and small investment requests.

Strategy 7: Seek Consent Not Consensus

Smart decisions reflect diverse opinions across disciplines, experiences, and outcomes. In today's collaborative mindset culture, teams strive to optimize each of these inputs. We listen to everyone's input and respond to it. We seek to bring everyone along. Everyone is treated as having an equal voice in the decision. Agility is compromised when people believe they need to make decisions together. In the end, the process is exhausting, and the decision is vanilla.

As you chase the decision, you are seeking consensus by trying to get to general permission by addressing all inputs. Consensus is where everyone's opinions are understood and a solution is created that respects those opinions. Consensus results in a solution that the group can achieve at the time.7 Note that it may not be the best solution as it is looking to accommodate everyone's input at a point in time. Majority approval often leads to minority decisions.

Some of the inputs are facts based on expertise, while many are opinions, a view, or judgment not necessarily based on knowledge. They are delivered with conviction or take on added weight based on positional authority. You will save time and effort by discounting this type of input.

Input is valuable. You should actively seek feedback, but that does not mean you need to act on all suggestions. As the decision owner, you have the right to consider, accept, or reject any input. Make sure to close the loop with whomever invested the time to share meaningful feedback. At a minimum, acknowledge and thank them for their contributions. Even better, go one step further to let them know you considered their input but are not going to take action on all of their feedback due to other factors you need to balance. This is perfectly acceptable. This is not only respectful but strategic as you are bringing people along. What you will find is that stakeholders often simply want to know they were heard. By bringing people along in this way you open up a dialogue and increase the likelihood they will support or at a minimum not object to the decision. It will achieve your goal of collaboration and minimize the headwinds when you share the final decision.

This alternate path leads to consent. Consent is about making a fast, smart decision informed by facts. Consent serves as a fast filter when considering feedback to identify major risks. This will not result in the perfect decision but in a faster decision. You can work through minor changes as you move forward by applying the concept of tacking that is discussed earlier in this chapter.

Applying This Step

We are talking about a quick two‐step process:

- Evaluate the quality of the feedback. Is the input based on facts or is it an opinion or judgment?

- Risk‐assess the input. Assess if the fact‐based input is a high, medium, or low risk to achieving the outcome.

The Perfect Decision Is an Illusion

The perfect decision does not exist. There is an inherent desire to make the perfect decision. We incorrectly believe the path to certainty is the data, but people are not rational, hence this perpetuates the chase. Being a poor decision‐maker will have a greater negative impact on your career than someone who can make decisions, learn, and course correct.

FIGURE 9.5 Mapping the steps to the decision moment

The seven‐step approach that is outlined in this chapter has been designed to be inherently followed in order. To stop chasing the decision, you should apply the appropriate steps to the situation at hand (see Figure 9.5).

Being an agile decision‐maker is essential to success. The speed of the decision is determined by both the decision‐maker and the decision‐requester. A good decision today is better than a perfect decision tomorrow.

Key Learnings ‐ Chapter 9

- Remember, Questions are king.

- Invest time framing the problem and defining success.

- Saying “yes” to one choice, means saying “no” to something else

- Recieving fast “no” is better than a slow “yes.”

- Realize no decision is a decision.

Notes

- 1. Ospina Avendano, D. (2020). Available at: www.toolshero.com/change-management/beckhard-harris-change-model.

- 2. Beckhard, Richard, and Reuben T. Harris. Organizational Transitions: Managing Complex Change. Reading, MA: Addison‐Wesley Publishing Company, 1987.

- 3. Available at: http://pastatenaacp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Beckhard-Harris-Change-Model-DVF.pdf.

- 4. Mdletye, Mbongeni, Jos Coetzee, and Wilfred Ukpere. “The Reality of Resistance to Change Behaviour at the Department of Correctional Services of South Africa.” University of Johannesburg, Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 5(3): 548. doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n3p548.

- 5. Available at: https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1018724/000119312516530910/d168744dex991.htm.

- 6. Iyengar, Sheena. The Art of Choosing, Paperback, Twelve; Reprint Edition. March 9, 2011.

- 7. Available at: https://circleforward.us/consent-is-a-third-option/.