Prologue: The Certainty Myth

We want to start by debunking two common myths. The first is the common view that you need to be a math savant to make decisions with data, which deters many people from using data for decision making. This is an erroneous belief. The reality is that making decisions with data is not a choice anymore, its a neccesity. Whether you were top of your class in math or not, you need to make data‐driven decisions. However, having deep math skills is not a core requirement to be a great decision‐maker. This is much like a race car driver who does not need to be a mechanical engineer but is a better driver given awareness of the underlying mechanics. Aptitude and depth in math are quite different from what is truly needed from a business leader—an appreciation for numbers and how they apply to your business.

The second myth is the illusion that, with the abundance of Big Data that surrounds us, we can finally get to the nirvana of making certain decisions—the perfect decision. The challenge in today's world is not the lack of information but the judgment to use it. This goes back to the first myth that you need to be a math whiz to make smart data‐driven decisions. Rather, you need to balance the information with human judgment, experience, and intuition. These ingredients are at the heart of what we call Quantitative Intuition (QI)™.

Consider the following scenario is quite familiar to many of us—the presentation has been going on and on. Slide after slide of numbers and figures. We are on slide number 25 and suddenly, you hear a sharp voice from the back of the room. One of the executives in the room raises her hand and announces, “Hold on, help me understand this, the revenue number at the bottom of this slide doesn't make sense, it doesn't match the production number you showed us before on slide 9.” What just happened? The executive did what good QI leaders do. She did not just evaluate the plethora of numbers at face value. She also avoided the temptation to simply look at the numbers in the table in front of her. She put the data in the context of her experience and the previously presented figures. Did she solve calculus equations or re‐run the spreadsheets multiple times in her head to make this statement? Did she need to be top of her class in math to identify a gap in the pattern and a flaw in the plan? No, possibly she used fifth‐grade math by multiplying the unit sold found on slide 9 by the price of the product to arrive at a sales figure on slide 25. In fact, her gut probably told her that the sales figure on slide 25 seemed off, which sparked her interrogative mindset. This type of interrogative mindset and the ability to put the data in context make for a good quantitative intuition‐oriented leader. It is the ability to correlate your gut intuition with the data, put the data in the context of the business environment, and ask precise questions.

Quantitative Intuition (QI)™

The list of examples of corporate and public policy failures is as long as history itself. It includes Coca‐Cola introducing the New Coke formulation and walking back its launch a few months later, NASA's decision to launch the Challenger space shuttle on an unusually cold night in Florida, or Juicero, a company that briefly made and sold high‐end Wi‐Fi–connected juice machines for $700 before disappearing. What is common to all of these examples, which we discuss in detail later in the book, is that the problem was not in the lack of data or the data itself, but rather in the judgment employed in converting the information to sound decision‐making. As data becomes more ubiquitous, and as our temptation to draw grand conclusions from it becomes more difficult to resist, it's critical that we chalk up case studies like these as invaluable lessons to learn. Decisions Over Decimals describes the Quantitative Intuition techniques to allow for better navigation through problem exploration to reach a sound decision more effectively.

Quantitative analysis is valued because it tends to be considered unambiguous. Numbers are a universal language that everyone speaks more or less uniformly. Humans tend not only to be terrified of failure but also of the unknown, so if we're given data that can be feasibly interpreted as solid, we tend to jump to two conclusions: first, that it will save us from failure, and second, that it will provide certainty. Both are categorically wrong.

Data and numbers tend to provide the comfortable feeling of accuracy and certainty, but they rarely tell us the full story. Numbers alone can never provide a perfect solution or answer, and they will never immunize decision‐makers from faltering. At the other end of the analytics spectrum, intuition—which is difficult to measure—often receives a poor reputation for being subjective and susceptible to biases and manipulations. And yet, intuition is visceral and grounded in understanding fundamental belifs, which in corporate terms is business acumen. The inner voice that you may work to ignore may be a guidepost along the way to a better decision if it is well contrasted and combined with the data.

Quantitative intuition (QI)—the combination of data and analytics with intuition—might sound like an oxymoron at first, but it is actually the key to effective decision‐making.

Simply put, QI is the ability to make decisions with incomplete information via precision questioning, contextual analysis, and synthesis to see the situation as a whole (see Figure P.1).

Quantitative thinking balanced with intuition is the necessary mix to make decisions in the data‐driven world we all live in. QI equips us to be more confident when making decisions in the face of uncertainty. By striking the right balance between data intelligence and human judgment, QI helps us navigate between risk and certainty.

FIGURE P.1 Quantitative Intuition definition

We live in a world of Big Data, yet we are always seeking more data, often questioning the data we have and feel frustrated by inaction. By allowing ever more data and analysis to drown out our human judgment, we neglect a powerful combination that can lead to a comprehensive view of a decision to be made. No amount of purely quantitative information will provide certainty and the answers needed to run an organization, grow a business, or lead a team. Combining quantitative information with intuition—human judgment developed through experience and close observation—is indispensable. Decisions Over Decimals busts the Big Data myth by putting forward a set QI techniques that teach you to bridge the gap between analytics and intuition.

So, what is intuition? In the context of decision‐making, intuition is human judgment developed through experience and observation. Intuition can be further defined with reference to three distinct features: it is a subconscious process, it involves parallel thinking (holistic, rather than sequential or analytical thinking), and it involves your “gut” as well as your brain. These three features are worth looking at more closely.

Intuition is primarily a subconscious process. Even if you use your conscious mind to formulate the problem or rationalize the result of intuitive judgment, intuition occurs without having to apply mental effort.

This distinction is elaborated in Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman's seminal book Thinking, Fast and Slow, in which the Israeli‐American psychologist and economist introduces the concepts of System 1 and System 2 thinking to describe the different ways the brain forms thoughts.

System 1 is rapid, automatic, and unconscious; it kicks in when we pull our hand away from a hot stove or step out of the street as we see a car racing toward us. System 1 is probably at work right now if you're a competent reader. You are making connections and associations without even realizing it.

System 2 is much slower, rational, and effortful. We rely on this system when we have to recall a series of numbers from memory or read a particularly technical passage of text. What's 45 multiplied by 97? Your system 2 just got to work.

Intuition falls squarely into the domain of System 1 thinking. It tells us the answer to something before we even know we know the answer. It gets us to the top of the stairs, both literal and metaphorical, before we even become aware of moving our legs.

The second characteristic of intuition is that it is parallel rather than sequential. When we employ intuition, we see a problem holistically, and simultaneously considering all of its features and components. Synapses fire furiously so that we can appreciate the whole picture swiftly, much like a talented chess player looking multiple moves ahead to map out the future consequences. In the context of decision‐making, analysts are trained to think systematically and sequentially about the steps of data analysis. On the other hand, decision‐makers are often required to, and benefit from, consuming and synthesizing different pieces of information in parallel to arrive at a decision.

Finally, intuition involves your “gut” as well as your brain. Of course, that's not physiologically accurate—our stomachs can't think—but when we say “use your gut,” we are talking about human judgment that feels visceral and instinctive.

One famous case study that demonstrates all three of these characteristics vividly, but particularly the last, is featured in Malcolm Gladwell's best‐selling book Blink. Gladwell recalls a researcher, Gary Klein, telling him a story of a team of firefighters being called to a burning house. The fire in the house appears to be coming from the kitchen, but when the crew tries to extinguish it with their water hoses, it continues to rage. After spending a few minutes in the burning house and observing the situation, the lead fireman tells everyone to evacuate the house immediately. Just seconds after they do so, the floor collapses. They likely would have been killed almost instantly if anyone had still been inside.

After the drama, it emerged that the source of the fire had not been in the kitchen but in the basement. But when asked what had triggered him to make the snap decision and urgently order everyone outside, the lead fireman was unable to give a real answer. He'd had no concrete information to inform a rational decision, but something had told him what had to be done. He purportedly felt it in his gut. He just sort of knew.

Something in this fire scene was different and surprising, which led the fireman to call the heroic shot to evacuate the house. Extensive questioning later revealed that the fireman had responded to subconscious clues and cues. Without knowing it at the time, he had noticed that the fire was unusually quiet and that the floor was much hotter than it should have been if the fire really had been in the kitchen. It was a combination of the “gut” and the brain, parallel thinking, that involved the eye observing the fires, the ears listening to the level of noise, and the sensation of heat that was much stronger than the fire he could see with his eyes. Data based on hundreds of other fires might have indicated that it was most likely to have started in the kitchen—because that's where fires in the vast majority of cases do start—but if the fireman hadn't heeded his intuition, events would have taken a far more tragic turn that day.

In life‐or‐death situations, intuition often takes over. Our System 1 dominates out of necessity—call it a primal instinct that humans have cultivated over millennia. But under different circumstances, as managers and decision‐makers in corporations, we rarely find ourselves in scenarios where decisions need to be made in seconds and with such high stakes. It is in those scenarios that we have the luxury of drawing on both intuition and quantitative knowledge and allowing one to make up for the shortcomings of the other.

Perhaps this seems too isolated and the circumstances unique. Most of us do not deal with life or death situations. How often would any of us sense there is an issue that quickly? Daily. You notice when there is a pause in the conversation with a colleague, and with no additional data, you begin to ask yourself questions to corroborate that intuitive spike. However, with family and friends, a shift in discussion topic or a delay in a response at the dinner table—or even in a text chat thread—begins to activate your intuition. For that signal to not become disruptive, you are best served correlating with facts and looking for the key to the new puzzle you were just presented—again this is QI.

Being able to combine qualitative thinking and intuition means possessing the ability to make confident decisions with incomplete information while counterbalancing our fear of failure. It means transforming different pieces of information into a decision by adopting a parallel view of all issues that matter, rather than just considering each piece of information separately and sequentially. Furthermore, it means enhancing our business acumen with the ability to spot patterns while also challenging how much value we are willing to attribute to those patterns and the data. We challenge patterns by asking the right questions: precise questions that are relevant and specific.

For many years, we have been teaching classes and programs on Quantitative Intuition™ at Columbia University, in Executive Education, and in custom private sessions for Fortune 500 companies. As part of the programs, we have asked executives to identify the aspect of decision‐making they think represents the biggest gap in their organizations when it comes to making smarter data‐driven decisions. We give them the options of the five steps of decision‐making:

- Defining the problem

- Data discovery

- Data analysis

- Insights or delivery

- Implementation

While each step involves both quantitative and intuitive elements, you can think of steps 1, 4, and 5 as the more intuitive steps (I in QI) involving leadership and management skills. Steps 2 and 3 can be thought of as the more quantitative steps (Q in QI) requiring mostly analytic skills. Across hundreds of business executives we surveyed, it became very clear that leaders find a much bigger gap in the intuition steps than in the quantitative steps. While some leaders pointed out that their organizations suffered from a lack of reliable data, the most common gaps were identifying the problems and converting the analysis to insights and actions. Now think about where we get the most help from external sources regarding data‐driven decision‐making. There is an abundance of companies selling us data and the newest, shiniest three‐letter acronym analytic tools. We get very little help defining the problem, generating insights, and converting these insights to actions. Decisions over Decimals is intended to bridge this gap.

This insight crystallized and focused our theory that business decision‐making often neglects powerful skills and tools. Like many of the failed business examples we previously mentioned, decision‐makers may feel confident or are hesitant, nervous, or conflicted when it comes to applying and acting on intuition.

To that end, this book will help you to develop both sides of the coin, the quantitative and the intuitive, and integrate Quantitative Intuition into your team's ways of working. It will serve as an aid when you're faced with small decisions that must be made briskly, but also when you're faced with weighty decisions with the potential to have a major impact on business, lives, and livelihoods.

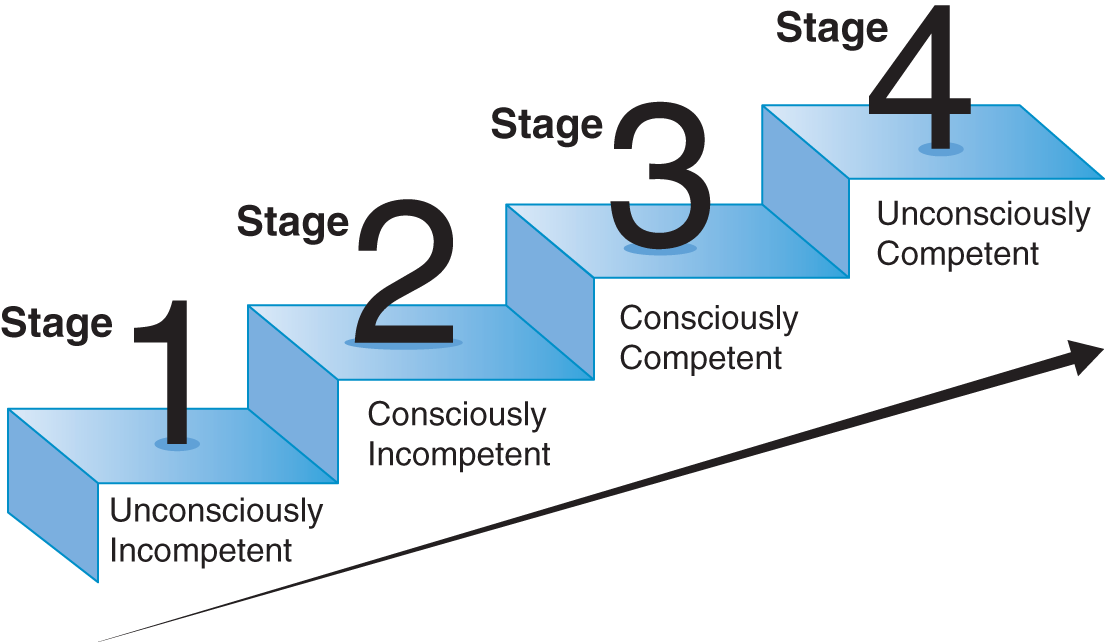

It is clear that quantitative skills can be taught. After all, we have been taught quantitative skills from a very young age, since kindergarten, if not earlier. But one of the questions we are sometimes asked is: “Can one really teach intuition? Isn't intuition something you're born with, something that, by definition, you either have or you don't?” The theory of learning suggests that many intuitive skills like walking, riding a bike, or driving can be taught. It is simply a matter of re‐application. In his book The Empathic Communicator,1 William Howell suggests that there are two important dimensions to learning: conciseness and competence. These two dimensions create the four stages of learning (see Figure P.2).

At the lowest level of learning, we are so clueless that we are unconsciously incompetent. We don't even know what we don't know. Then, in the next stage of learning, we are consciously incompetent. For example, we buy a book like Decisions Over Decimals, watch a TED talk, or attend a online course and we start realizing the limits of our knowledge. For example, we learn that there is something called Quantitative Intuition, but we don't know yet exactly what it is. Then as we progress reading through the first few chapters of the book, we not only understand what QI is, but we also start to learn a few new skills that we jot down to try at work. We are transitioning to the third stage of learning. We are consciously competent. We are ready to start implementing the new skills we have learned, but it requires effort. It requires System 2 thinking, consciously and carefully thinking about what we do. Think about a toddler who is just starting to walk. They need to put all their cognitive capacity toward taking the next step without falling. If you are an experienced driver, think about your first few days driving. You were probably very proud of yourself for being able to competently maneuver the four‐wheeled metal box. Still, you had to dedicate your full attention to operating the car while paying attention to the road conditions and the other cars on the road. You probably couldn't even fit into your cognitive capacity a conversation with your fellow passenger while driving. You were consciously competent at driving. At the highest level of learning, the nirvana of learning, you get to the fourth and final stage. You are unconsciously competent. This stage is often referred to as habit or second nature. You have exercised the skill so frequently that it became like second nature, it became intuitive. You have just learned intuition. Think about walking, driving, or riding a bike. These activities that you had to learn at some point in time became intuitive through re‐application. Think about our leader from the example at the start of this prologue who compared figures across slides. At the start, it was difficult, she had to pay close attention to do this, but now we know that she does it in almost every presentation; we learn to almost expect it from her. As you learn the different QI skills and tools throughout this book and start exercising them, these skills will also become intuitive for you.

FIGURE P.2 Dimensions and stages of learning

Broadly, the book is divided into three parts:

The first part, Precision Questioning (Chapters 1–3), is devoted to assessing the situation, effectively framing an issue, and identifying the question we seek to ask and subsequently answer. We believe that the most intelligent person in the room is not the one with the right answers but the one with the smart questions. Questions expose, reflect, and test assumptions transforming the data‐driven journey from problems to actions. We provide you with several tools to help you focus on the essential questions.

The second part of the book focuses on Contextual Analysis (Chapters 4–6), developing intuition and exercising the ability to move confidently from data, through analyses, to business problems and decisions—challenging and interrogating the data and analyses, but only when it is relevant to the problem and decision at hand. We introduce the Fermi estimation methods and teach you to develop “numbers intuition” through approximation and back‐of‐the‐envelope calculations. You will learn how to become a fierce, intuitive interrogator of data. How to put data and analysis in the context of your business and the decision at hand.

The book's final part (Chapters 7–10) centers on Synthesis by transforming analyses to insights, insights to actions, and actions to outcomes. While traditional data analysis techniques promote a systematic approach of summarizing data to inform actions, this essential section encourages parallel thinking to synthesize the data and insights to enable agile decision‐making. It also illuminates the importance of effective communication to inspire action.

Across the three pillars of the QI approach—Precision Questioning, Contextual Analysis, and Synthesis—we first teach how to decode data and analytics, understand their limitations and values, and scrutinize and question them in the most effective way.

This book is a handbook on Quantitative Intuition. Quantitative and Intuition sounds like an oxymoron, but as you dive into the chapters, you will not only apreciate that it's possible to combine data insights with intuition, but in fact it is the best way to make smart decisions.

Why Quantitative Intuition™

While we have promoted the value of intuition and listening to your “gut,” do not mistake our message to suggest that you should fully rely on your intuition and abandon the data. The main reason to combine intuition with data is that intuition alone can steer us wrong due to a host of biases. Biases in decisions can creep in both because one does consult data when making decisions and often looks at the data through a biased lens, and because one ignores data and relies solely on inuition.

Management and business writers love reciting stories of advice that were thought of as canny at the time of its delivery but later turned out to be wildly misguided. American astronomer Clifford Stoll is regularly mocked for a 1995 article he penned for Newsweek calling the internet a “trendy and oversold community.” We relish that IBM chairman Thomas Watson famously forecasted that the world would be able to accommodate “maybe five computers.” And even Albert Einstein's 1932 observation that there's not “the slightest indication” that nuclear energy will ever be obtainable is still regularly met with chuckles of incredulity. But the truth is that we've all suffered the same fate at one point or another, albeit perhaps not in relation to a concept that revolutionized the world in quite such a dramatic way. One such famous example of a statement that was found to be vastly erroneous in light of history was a Yale professor's comment to the founder of FedEx, Fred Smith, when he proposed the idea of FedEx as a student in college (see the call‐out box, “In Order to Earn Better than a ‘C' the Idea Must be Feasible”). So why do such intelligent and experienced individuals make such erroneous predictions? The main reason is that people suffer from biases that can steer them wrong. As a subpopulation of society, leaders often suffer from similar, and in some cases even more pronounced, biases.

Heuristics can generally be defined as rules of thumb or shortcuts that the human brain uses to draw conclusions or make decisions about something. These heuristics are at the heart of Kahneman's System 1 thinking that we discussed earlier. They allow us to move on with our lives and fit everything we need to do within the 24 hours we have each day. Sometimes these heuristics are entirely adequate and serve as a perfectly good conduit to get us to where we need to be, but other times they lead us entirely astray and cause us to make decisions and judgments that turn out to be flawed. Biases are particularly important to understand in the context of intuition. Their existence certainly doesn't make intuition any less valuable as a component of good decision‐making, but it is critical to be aware of biases that may arise from intuitive decision‐making. Understanding biases and knowing how to navigate them is the first step in attempting to avoid them.

The beauty of the human race—what makes life interesting and worth enduring—is that individuals are not robots. We all have opinions that are shaped by factors we're not aware of, by preconceptions we don't know we have, and by beliefs we don't know we hold. The decisions we make will always be affected by bias. But to be the most effective decision‐makers, to be able to foster and develop our quantitative intuition, we must be aware of the presence of biases and the impact they having on us in order to check them, control them and minimize them wherever possible.

Many books have been written about biases in decision‐making. Our objective here is not to survey this literature, but rather to highlight when and how those biases can affect our intuitive mind as well as our quantitative thinking. When working purely based on intuition, some biases can become more prevalent because we do not have data to prove our intuition wrong. On the other hand, a different set of biases can arise when looking at data from a biased perspective.

Biases from Working Intuitively

Probably the most prevalent bias that prevents decision‐makers from consulting data is overconfidence. Overconfidence is a particularly powerful source of illusion and it is therefore extremely important to be aware of it when relying on intuition as a tool for making decisions. The cruel nature of overconfidence is that it is hard to identify, purely because we often don't know what we don't know. Or in other words, we're so confident that we know the answer to something that we don't even entertain the idea that we might be mistaken. This is a recipe for disaster when it comes to data‐driven decision‐making as overconfidence in our erroneous conclusions prevents us from seeking the possibly correct answer in the data. In fact, and this might seem surprising, as leaders and experts in a given field tend to be more prone to the overconfidence bias than nonexperts precisely because they think of themselves as likely to be correct.

Overconfidence's bedfellow, if you will, is the optimism bias. Many studies have shown that when entrepreneurs are asked to estimate the chance of their business succeeding, they're likely to predict a much higher likelihood of their business' success than if they're asked more generally about the chance of a business just like theirs doing well.2 Indeed, because of their strong conviction in their idea, entrepreneurs often tend to overly rely on intuition and neglect data points that hint at risk to their idea (see call‐out box ‘”Overconfidence, Optimism, and the $700 Juicer”).

Another bias that tends to appear when decision‐makers rely mostly on their intuition and the available information is the availability bias. In short, that availability bias suggests that people use the most available information to make a judgment. Humans tend to think an event is more likely to occur if it's easily imaginable or if a specific example of a similar event occurring is easy to recall. For example, if 100 individuals were to be divided into two groups, with members of the first group asked to estimate the annual number of murders in Detroit and members of the second asked to estimate the annual number of murders in Michigan, the mean estimate in the first group is very likely to be higher than the second even though murders in Detroit (the capital of Michigan) would necessarily only represent a subset of overall murders in the entire state of Michigan. Why? Because people are more likely to recall headlines and news bulletins about murders in Detroit than in Michigan.3 Such headlines are likely to be more striking and that's where the availability bias comes in. Similarly, populations regularly overestimate the number of yearly deaths due to shark attacks because the ones we hear about are so dramatic or remarkable that they're hard to forget, and the ease of imagining such events thanks to movies like Jaws.

But bringing in data is not always a cure for biases. The data itself may spark its own unique set of biases.

Biases from Working with Data

When looking at data, sometimes we see things that aren't there; we recognize patterns that don't exist and, at the same time, we entirely miss patterns that are there. One widely cited example of this comes from an experiment created more than two decades ago by two academics to test the idea of Selective Attention.6 Study participants were asked to watch a video in which two teams, wearing black and white shirts, are shown passing a basketball. Participants in the study were tasked with paying close attention and counting how many times the players in the white shirts passed the ball between them. About halfway through the short video, somebody in a large gorilla costume walks straight into the middle of the game, stands still, pounds their chest for a few seconds and then leaves again.

When participants were questioned about their observations afterward, many could correctly say how many times the players passed the ball, but fewer than half of all the participants said that they noticed the interrupting ape. And even after being told what had happened, the majority claimed that there's no way they could have missed such a noticeable thing. This is a great example of how focusing on specific aspects of data may distract you from seeing other things in the data, even if it is literally a gorilla in your data.

The context in which a decision is made introduces us to another set of relevant biases. The anchoring bias dictates that humans tend to overvalue the first piece of information that's provided to them when compared to subsequent data points. Think of the impact of anchors in salary negotiations, for example. The sheer power of anchoring can be quite striking, as demonstrated through an experiment that was conducted while teaching MBA students. In the study, students in an MBA class were asked to bid on a good bottle of wine, but before opening the auction, students were asked to write down on a piece of paper the last two digits of their social security number. Despite the fact that these students are, for the most part, highly intelligent and consider themselves to be largely rational, and although they would scoff at the idea that their social security number is in any way related to how much they're willing to bid on wine, time after time the experiment revealed a surprising result. Students for whom the last two digits of their social security numbers are above 50 tend to bid more than those whose numbers were below 50. Entirely random numbers that students were asked to write down before making a bid impact the choices they made even if they were acutely aware of the fact that these numbers have nothing to do with the decision or its outcome.

Now take the anchoring bias to a business meeting environment, say a meeting around projections for next year's operation. The meeting starts and someone throws into the air their projection for next year's sales. At this point, all numbers are likely to be anchored toward the number that was voiced, whether it was right or wrong. Even those who think the number mentioned is way too high or way too low will likely anchor their new estimate toward that number. Even worse, if the first number thrown into the air comes from a leader, the anchoring bias is likely to be stronger. But leaders are often the first to speak in any business meeting, making the likely anchoring more pronounced in practice. We have two practical pieces of advice to mitigate the anchoring effect in business settings. First, if the meeting is around a specific number, at the start of the meeting, ask every person in the room to write down on a piece of paper their estimate for the number. That way, when the discussion starts and people are susceptible to other anchors, they will at least be also anchored toward their initial estimate. Second, if you are the leader in such a meeting, speak last to avoid anchoring others to your views.

An important bias that is particularly troubling when people look at data is the confirmation bias. Confirmation bias means that we tend to overweight and overvalue information and data that explicitly supports our initial opinion or belief about something. As we discuss later in the book, becoming a fierce interrogator of data, asking questions such as “What data am I not seeing?” or “Who delivered the data and why?” can help identify instances of confirmation bias.

Other biases related to looking at data include conservatism bias, which presents itself in people tending to favor older information and undervaluing new data points, and information bias, which describes the tendency to seek new information even if it is not directly relevant to the decision that we're trying to make. We revisit that last bias again and again over the following chapters of this book as we seek to underscore why certainty—and the perfect decision—is entirely unattainable.

Notes

- 1. Howell, William Smiley. The Empathic Communicator. Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1982.

- 2. Salamouris, Ioannis S. “How Overconfidence Influences Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 2013, 2(1): 1–6.

- 3. Kahneman, Daniel, and Shane Frederick. “Representativeness Revisited: Attribute Substitution in Intuitive Judgment.” Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment, 49 (2002): 81.

- 4. “2013 State of the Industry: Juice & Juice Drinks.” Beverage Industry, July 10, 2013.

- 5. “The Great Juice Rush of 2013.” QSR, March 2013.

- 6. Chabris, Christopher F., and Daniel J. Simons. “The Invisible Gorilla: And Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us.” Harmony, 2010.