Chapter 2

Knowledge: the

strategic

imperative

Every few years a new management philosophy captures the attention of strategists and business leaders. In the 1990s, such movements have included those of total quality management and, more recently, business process re-engineering. The last few years have seen knowledge take centre stage. Many consultants, organizations and suppliers have jumped on to the knowledge management bandwagon, relabelling their wares to match. Does all the hype mean that it is merely a passing fad or is it something more fundamental?

This chapter unravels the fad from the fundamentals. The origins of the current interest are traced to several well-established roots, including information management and the learning organization. The different ways in which knowledge can be applied as a core component of strategy are described in terms of seven knowledge levers. Essential knowledge processes are depicted as two knowledge cycles. One cycle consists of the processes used in innovation and the other those used in knowledge sharing. The chapter concludes with a review of opportunities and challenges.

Fad or fundamental?

It is easy to dismiss the interest in knowledge as a passing fad. Indeed, 47 per cent of British managers in a 1997 study by Cranfield School of Management expressed this view, although studies one year later shows this figure down to 2 per cent.1 Closer analysis shows that knowledge has been gaining importance over two decades and that many organizations have already gained significant benefits through applying knowledge-based strategies.

The momentum of knowledge

Interest in knowledge is not new. Greek philosophers, such as Plato and Socrates set out key principles that have stood the test of time. Often quoted in business circles today is Francis Bacon’s observation made at the end of the sixteenth century: ‘knowledge is power’.2

In recent times several management writers have highlighted the role and contribution of knowledge in business strategy. Peter Drucker is credited with coining the phrase ‘knowledge worker’ in the 1960s. Over a decade ago, he was writing about the role of knowledge in organization in some depth.3 Other foresighted writers include Masuda (1980), Sveiby and Lloyd (1987), Nonaka (1991) and Stewart (1991).4 Even so there was no widespread interest in the topic of knowledge among most business managers until just a few years ago.

Now the level of interest has exploded. From a mere handful of international management conferences in 1995–6, there were well over twenty-five in 1997. Each month sees the arrival of several new books. Several new periodicals devoted specifically to knowledge management were launched in 1997, including the Journal of Knowledge Management and Knowledge Management Review. My colleague Debra Amidon has traced the momentum of knowledge as a set of timelines – Hindsight, Insight and Foresight – in her The Ken Awakening where she writes that the momentum of knowledge management: ‘has now reached a stage of critical mass of insight. Dedicated expertise across all disciplines are exploring and defining new management practices fundamental to capitalizing upon the knowledge based economy’.5

Established roots

The current interest stems from several well-established roots (Figure 2.1).

1 Business transformation. Knowledge management is seen by many companies as a natural adjunct to other business transformation initiatives, such as TQM and BPR. Property and insurance company CIGNA re-engineered its underwriting processes, in which it incorporated knowledge of its best underwriters.

Figure 2.1 The roots of knowledge management

Source: Skyrme, D. J. and Amidon, D. M. (1997). Creating the Knowledge-Based Business: Key Lessons from an International Study of Best Practice, Business Intelligence

2 Innovation. The quest for better and faster innovation is leading to a focus on knowledge flows and networking in firms’ innovation processes. Speciality chemicals company Unichema applies knowledge management to improve its innovative capabilities. An example is the use of conceptual modelling to map Unichema’s collective knowledge of soap-making.

3 Information management. Professional services organizations, such as legal firms and management consultancies, have long recognized the value of well-managed information resources. Booz Allen & Hamilton’s information specialists collate corporate knowledge into Knowledge Online, a networked set of databases accessible throughout the organization.

4 Knowledge-based systems. Those who developed and used expert systems in the 1970s and 1980s argue that they have been practising knowledge management for many years. Their systems hold the distilled knowledge of experts, captured as a set of rules for use in diagnosis and problem-solving applications. Despite their chequered history, such systems are increasingly found as part of a knowledge management programme. One example is the assessment of risk for new insurance proposals at Thomas Miller & Co.

5 Intellectual assets. As noted in Chapter 1, the underlying value of many companies is not in their physical assets, but in their intellectual assets such as know-how. Skandia has systematically developed measures of its intellectual capital. These are used as a key management tool in developing its position in the insurance market.

6 Learning organization. The ‘learning organization’ has its origins in companies like Shell, where Arie de Geus described learning as the only sustainable competitive advantage. A learning organization continually develops its competence, for example by learning from its successes and failures. Learning and knowledge go hand in hand, as Harvard professor David Garvin has noted: ‘A learning organization is an organization skilled at creating, acquiring and transferring knowledge, and modifying its behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights’.6 Companies that started with learning initiatives in the mid 1990s, such as Glaxo Wellcome and Anglian Water, have now broadened or repositioned these as knowledge initiatives.

Today’s knowledge agenda draws on the skills and practices used in these different disciplines to create winning strategies based on knowledge.

Knowledge is different

One of the practical problems in developing strategies for exploiting knowledge is its complex nature. The word ‘knowledge’ is frequently substituted for ‘information’ in various methods or products. This is too simplistic and ignores some distinctive differences.

What is knowledge?

Knowledge takes many forms. There are facts, there is the knowledge to perform a certain task having learnt a particular skill, and there is knowledge that something is right, according to your personal beliefs. Many classifications have been developed to distinguish these and other types of knowledge. Most are somewhat academic and in practice matter hardly a wit.7 Whatever classifications others use, most managers can readily identify what knowledge is important to them in their job, and what is crucial for their organization’s success. Perhaps the most practice-oriented categorization is that cited by Charles Savage:8

• Know-how – a skill, procedures.

• Know-who – who can help me with this question or task.

• Know-what – structural knowledge, patterns.

• Know-why – a deeper kind of knowledge understanding the wider context.

• Know-when – a sense of timing, and rhythm.

• Know-where – a sense of place, where is it best to do something.

Figure 2.2 A knowledge hierarchy

Some of the more critical types of knowledge needed by managers are those that are more judgemental, such as ‘know-why’ and ‘know-when’.

Another popular classification schema is that of a knowledge hierarchy (Figure 2.2). Amidon offers some typical definitions of its elements,9 to which I have appended examples:

• Data– facts and figures. Example: 03772 41565 83385 10157

• Information – data with context. Example (from above data): Heathrow weather station; visibility 15 km, sky completely cloudy; wind direction north-west , speed 85 kts; temperature 15.7 °C.

• Knowledge – information with meaning. Example: My experience indicates that this weather will cause severe flight delays.

• Wisdom – knowledge with insight. Example: I will book a train through the Channel tunnel before all the other passengers find out about this more reliable alternative.

There are many such hierarchies and definitions of information and knowledge, often conflicting. For practical purposes, the precise distinctions of different authorities matter little. More important is that within whatever hierarchy is used there is a clear distinction between two types of knowledge, often referred to as explicit and tacit knowledge. According to Nonaka and Takeuchi explicit knowledge is that which ‘can be expressed in words and numbers and can be easily communicated and shared in the form of hard data, scientific formulae, codified procedures or universal principles’,

whereas tacit knowledge is ‘highly personal and hard to formalize. Subjective insights, intuitions and hunches fall into this category of knowledge’.10

The concept of tacit knowledge was described in depth by Polyani who wrote that ‘we know more than we can say’.11 He used the example of a skater. Could a skater describe explicitly what he or she does, such that another person can follow suit? Like riding a bicycle, you acquire the knowledge to do so not through the written word, but the physical experience, and perhaps a guiding hand.

Another facet of knowledge that is important in practice is the degree to which it is shared. Boisot describes this axis of knowledge as diffu-sion:12

• Personal/individual knowledge – known only to those who create it or conceptualize it.

• Shared – diffused to others, often by personal interaction with the creator.

• Proprietary – known widely within an organization, but protected from widespread external use.

• Public – readily available on the open market.

Generally, tacit knowledge is the most valuable knowledge that an organization possesses. It resides in the heads of employees and stakeholders, especially customers. However, people leave organizations, and walk away with their knowledge. The crux of a knowledge strategy is therefore to seek ways of turning personal tacit knowledge into organizational knowledge. The two complementary approaches are:

1 Converting it into a more explicit form – in documents, processes, databases etc. This can be considered as the ‘Western tendency’ since this is the main emphasis of many European and US knowledge programmes.

2 Enhancing tacit knowledge flow through better interaction, such that the knowledge is more widely diffused around the organization and not held in the heads of a few. The Japanese and Eastern cultures excel at this type of diffusion, through various socialization activities.

Methods used in these approaches are described in Chapter 7.

Characteristics of knowledge

In Chapter 1 it was noted that knowledge defies normal economic rules. Harlan Cleveland, writing in his eminently readable book, The Knowledge Executive, describes six special characteristics of information or explicit knowledge.13 It is

1 Expandable. Unlike other resources that are managed because of their scarcity value, the more it is used the more is generated.

2 Compressible. It can be summarized for easier handling and can be packaged into small physical formats.

3 Substitutable. In many situations it can replace physical and other forms of resource. Thus telecommunications reduces the need for physical transport.

4 Transportable. It can move from place to place, quickly and easily, ready for collecting when the recipient chooses.

5 Diffusive. It tends to leak. As technology improves, it become ever more difficult to stop reproduction and transmission.

6 Shareable. If it is given to another person, the first person does not lose it.

Tacit knowledge is also expandable, diffusive and shareable, but is not as easily transmitted or diffused. It is intangible and difficult to identify and describe. It is context dependent. These characteristics present some interesting management challenges. Making knowledge explicit means that it can be more readily copied, diffused and shared. On the other hand this makes it ‘leaky’, and it could reach undesirable parties. The increasing rate of knowledge generation means that much existing knowledge has a short ‘half-life’ and its value decays quite quickly. It needs constant refreshing and revalidating through use.

The knowledge agenda

Two thrusts

The strategies used in various knowledge initiatives can be distilled into two broad thrusts:

1 Knowing what you know – better awareness, sharing and application of existing knowledge, including that which originates outside the organization.

2 Faster and better innovation – more effective conversion of ideas into products and processes.

Knowing what you know

Many organizations under-utilize much of their existing knowledge, because its existence is unknown to those who need it. In one case, a department of AT&T spent $79 449 to glean information that could be found in a publicly available Bell Corporation Technical Information Document, priced $13!14 Has your customer service department spent long hours working out how to deal with a problem, when another department has the solution at its fingertips?

Lost knowledge can have tragic consequences. The crash in 1996 of a Second World War fighter aircraft and the death of its pilot could have been averted if he had known of a simple fix to a problem of losing fuel pressure when flying upside down. The fix was well known to wartime engineers, but unfortunately only came to light at the crash inquiry. A similar situation confronts the nuclear power industry. Many of the engineers who built nuclear power plants in the 1950s and 1960s are retiring, yet these plants will need to be decommissioned at some time in the future. Is there some vital knowledge, known to these engineers, that will make the decommissioning process less hazardous?

It is too easy to mislay knowledge that might be needed in the future, or to be unaware of existing knowledge that could bring business benefits today. Texas Instruments’s TI-BEST programme provides a good example of the benefits of ‘knowing what you know’.

TI-BEST: sharing best practice at Texas Instruments

Jerry Junkins, when CEO of Texas Instruments, issued this challenge to his leadership team:’If only we knew what we knew. We can not tolerate having world-class performance right next to mediocre performance, simply because we don’t have a method to implement best practices.’15

Thus was born the TI-BEST (Texas Instruments Business Excellence Standard) programme in 1994. A fifteen-member steering team was created to develop and roll out the programme. It created best practice databases containing over 500 best practices and a facilitators network. The 200 or so facilitators spend 30 to 50 per cent of their time networking, facilitating knowledge transfer from one part of the 60 000 strong organization to another. There was also a company-wide event, the ShareFair, that brought together people for seminars, knowledge sharing and the inauguration of an annual ‘Not Invented Here, But I Did Anyway’ award. By 1997 Texas Instruments had increased its yields at its thirteen fabrication plants to create the equivalent capacity of one new facility. Hence this benefit of sharing best practice is described by insiders as ‘one free fab plant’.

Faster and better innovation

In striving for better innovation many managers I meet bemoan the lack of creativity in their organizations. In my opinion creativity is abundant. Creativity and idea creation is simply the starting point of innovation. What most organizations lack is the knowledge infrastructure and processes that converts this abundance of ideas into new products or processes. Amidon describes the percentage of ideas that are converted as the Innovation Quotient. She finds that it is ‘woefully low’ in most organizations.16 Better innovation comes through increasing this ratio and in retaining ideas that might be initially discarded, but could be of benefit later.

Viable ways of doing this become apparent if innovation is reconcep-tualized as a set of interacting knowledge processes:

• the absorption of existing knowledge from the external environment

• the creation of new knowledge through creative thinking and interchange of ideas

• the rapid diffusion of ideas and insights through knowledge networking

• the validation, refining and managing of innovation knowledge

• the matching of creative ideas to unmet customer needs and unsolved problems

• encapsulating and codifying knowledge into an appropriate form, such as a tangible product, a description of a new internal process, training material for a new service, a marketable design, patent, etc.

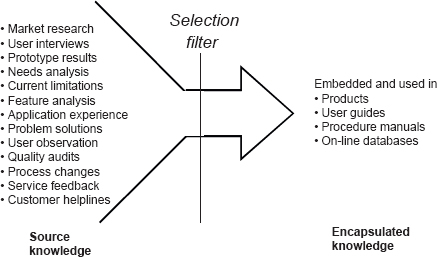

Throughout the innovation process, knowledge is continually being converted from tacit to explicit and vice versa. It flows between people, gets codified into designs and databases, is disaggregated and recombined, restructured into new forms and so on. This rather complex, even chaotic, view of innovation does not easily lend itself to systematic management. Nevertheless, it is a management responsibility to coax out new ideas and steer the promising ones along an idea-to-production pipeline (Figure 2.3). In general, as knowledge progresses through the pipeline it becomes more reproducible and costs less to distribute.

Figure 2.3 Innovation as knowledge refining

Seven levers of strategy

What can be done to secure a strategic advantage through knowledge? Analysis of many cases indicates seven commonly used levers:

1 Customer knowledge – developing deep knowledge through customer relationships, and using it to enhance customer success through improved products and services.

2 Knowledge in products and services – embedding knowledge in products and surrounding them with knowledge-intensive services.

3 Knowledge in people – developing human competencies and nurturing an innovative culture where learning is valued and knowledge is shared.

4 Knowledge in processes – embedding knowledge into business processes, and giving access to expertise at critical points.

5 Organizational memory – recording existing experience for future use, both in the form of explicit knowledge repositories and developing pointers to expertise.

6 Knowledge in relationships – improving knowledge flows across boundaries: with suppliers, customers, employees, etc.

7 Knowledge assets – measuring intellectual capital and managing its development and exploitation.

The core levers are knowledge in people, processes and products. In most situations winning strategies are developed by concentrating on just two or three of the seven levers.

Customer knowledge

Virtually every survey ranks customer knowledge as an organization’s most important knowledge. In truth, most companies know a lot less about their customers and their markets than they claim. They place too much reliance on traditional market research. They carry out customer satisfaction surveys that tell them little of customers’ real wishes and concerns. Customers can provide vital insights into the application of your products and services, but this requires forging close working relationships that surface this deep knowledge.

Companies like 3M and Steelcase encourage their researchers and engineers to spend time with the users of their products. Steelcase, a manufacturer of office furniture, makes video recordings of people working with prototypes in different environments, such as offices, airports and hotels. Through such methods, customer knowledge is deepened and new insights are gained.

Developing good customer knowledge also needs effective environment scanning and market intelligence systems to gather and collate knowledge. Such systems should cover not just customers and markets but a whole range of external factors including technology, social, political, economic and regulatory developments.

Knowledge in products and services

Almost every product is knowledge intensive, even if we don’t realize it. When we buy a prescription drug, we are not buying merely a tablet but also the knowledge it encapsulates, that of the therapeutic benefits and side effects gleaned from years of extensive clinical trials. We can use genetic knowledge to create genetically modified foods, such as disease resistant potatoes or square tomatoes that are easier to pack.

Companies hold vast amounts of knowledge that can be exploited as part of their product or service offering. Such knowledge includes applications knowledge, market knowledge, and how to solve problems encountered by users. Much of this is accumulated during the product development and testing process, but is then overlooked. Only a fraction is encapsulated into the final product, leaving under-utilized a rich source of knowledge that could create additional revenues (Figure 2.4).

This knowledge can be exploited in several ways. One way is through additional paid services, such as consultancy or training services. Another way is to make the product ‘smart’ or ‘intelligent’. There is an intelligent oil drill, which ‘knows’ the shape of the reservoir it is drilling, and so extracts more oil.

Products and services can be customized by combining product and customer knowledge. One example is the personalized daily news bulletin that combines information from many disparate sources. Another is Campbell Soups’ ‘Intelligent Quisine’, designed for people suffering hypertension or high cholesterol. It delivers weekly packages of nutritionally designed, portion-controlled meals based on personal information.

Figure 2.4 The codification filter

You can also exploit knowledge that is generated as a by-product of your principal activities and turn it into a business opportunity. The Automobile Association in the UK operates motorists’ rescue services, from which it builds an ever expanding database about its customers and their needs. This has helped it add many new lines of insurance business, some related to motoring needs, such as holiday travel, but others in new areas, such as household insurance. Perhaps the best known example is American Airlines’ reservation system SABRE, which was run as a separate business, and in some years has made more profit for its parent company than flying their aircraft!

Knowledge in people

‘People are our most valuable asset’ runs the line in many company annual reports. Companies that truly believe it apply this knowledge lever through a competence or learning lens. One underlying model used in this approach is that of a repeating action-learning cycle:

• Plan: think, conceptualize, devise a set of actions.

• Act: do, gain experience of ‘theory in practice’.

• Observe: record experiences, share knowledge with others.

• Reflect: consider what has been learnt and how it can be used to make improvements.

Learning programmes typically mesh competence development activities at several levels – individual, team and organization. Individual competence and knowledge is developed through personal development plans that meet the needs of individuals as well as the organization. Team knowledge is enhanced through learning processes that encourage individuals to share their knowledge in teamwork. At the organizational level the focus shifts to overall competence measurement, corporate universities and human resource policies that reward learning and knowledge sharing. Motivating knowledge workers so that they work energetically and are committed to the success of the organization is another important aspect of a people-focused knowledge strategy.

In reality, many organizations fail to effectively use the knowledge in their people. They allow insufficient time for learning or reflection. They regard people as hired hands, rather than borrowed brains. They dictate to them what to do, giving them little discretion in how they do it. It is little wonder that their employees feel undervalued, and will indeed ‘walk’ at the first opportunity and take their knowledge with them.

In contrast, Shell is an organization long acknowledged as an excellent example of nurturing and developing its people. It has an initiative within its exploration business to ‘harness this talent’ and make ‘better use of this intellectual capital’. Its focus is the development of an infrastructure for learning and leverage of knowledge. There are open learning centres and databases of learning resources on the company’s intranet. However, the most significant developments have been the establishment of knowledge communities and developing skills for quality person-to-person dialogue and reflection. Learning is being built into daily work activities.

One company that combines both product and people levers is that of Teltech Resources.

Teltech – people are the product

Teltech Resources of Minneapolis manages a knowledge network of some 3000 human experts whose knowledge is harnessed to tackle difficult problems. This network includes academics, industry experts and recent retirees who have specialist in-depth technical knowledge. Knowledge analysts provide a human interface between the client who has a problem, the expert network and over 1600 technical databases.

Teltech’s business is based on a deep understanding of how its clients gather and use knowledge. It then develops close relationships with both suppliers and users of that knowledge. It also blends explicit and tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is structured according to a well-developed thesaurus of knowledge domain classifications. This also permits many synonyms, cross-referencing and multiple placements. Analysts ‘act as guides in defining, clarifying and interpreting database-search results’.

In one case, a medical products developer had tried in vain to make a heart pump leak-proof in a saline solution. The answer came from an expert in submarine technology, whose equipment also operates in similar environments.17

Knowledge in processes

Every business process contains embedded knowledge. Ad hoc activities, previously performed by people with specialist knowledge, become codified into routine processes. It is then more readily diffused throughout an organization. Even so, much tacit knowledge is frequently needed to perform the process effectively and to deal with exceptions. Hence the explicit process knowledge is typically accompanied by training, procedure manuals and access to experts.

One way to enrich knowledge in processes is to embed backup resource material. When CIGNA re-engineered their underwriting processes, much of the contextual information that did not get coded into computer procedures was made available at the click of a mouse. Increasingly, access to human expertise is available on such systems through a ‘click here for help’ screen icon. This may either trigger an email or even a computer-generated phone call to a human expert. Other organizations use workflow software to blend computer held knowledge with human knowledge. The software applies rules to determine which transactions are straightforward, and are therefore handled automatically by computer, and which require human intervention.

Organizational memory

This strategic lever helps address the issue of ‘knowing what you know’. It is also used to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, and to draw lessons from similar situations or cases from elsewhere. Organizational memory exists in many places, most notably the brains of its people. But it also exists in records, filing cabinets, personal computer disk files and the physical surroundings. External sources should not be overlooked. After all, many outsiders follow an organization’s actions, or have even been part of it at one time. As a consultant, I know only too well that clients use me as part of their organizational memory. They request a copy of an assignment report that they cannot now locate, since those who commissioned it have moved on!

A common approach to managing organizational memory is to capture in explicit form the most important knowledge and enter it into knowledge databases. These databases may be in document management systems, in groupware such as Lotus Notes, or as web pages on an intranet. Often such databases will not contain the knowledge per se, but will provide pointers to it. Examples of knowledge databases include:

• Customer histories. These detail interactions with a given customer: products bought, sales visit reports, etc.

• Best practices. Chevron has best practices databases and a resource map organized according to the categories of the Baldridge quality award.

• Products and technologies. Details of the organization’s various products and history.

• Bid boilerplates. ICL’s Café Vik holds information used in previous project proposals. In a typical situation 80 per cent of information for a project bid is quickly assembled from existing material, freeing up time for the bid team to concentrate on activities that could clinch the sale.

Explicit knowledge bases, however, typically contain less than 10 per cent of an organization’s memory. Therefore other approaches are used to make it easier to access the minds of experts. A common example is an on-line directory of expertise, often called Yellow Pages, because they are structured by skill and discipline, not by department. Novartis have also added Blue Pages that contain details of external experts with whom they collaborate. Knowledge-sharing events provide another way of sharing tacit knowledge. Thomas Miller & Co., a mutual insurance company, runs ‘knowledge in a nutshell’ events. Company experts give talks on their areas of expertise and describe their experiences. These live sessions are also recorded on video for further distribution and subsequent recall.

The key to enhancing organizational memory is to make ongoing experience capture an integral part of everyday work. Techniques include decision diaries, learning histories and post-project reviews.

Knowledge in relationships

Many companies have an invaluable resource of knowledge developed through individual relationships – with customers, suppliers, business partners, professional and trade associations. When a salesperson leaves your company, it is not just their product or customer knowledge that is lost. It may be much of the customer relationship. This relationship involves shared knowledge and understanding – not just of needs and factual information, but of deeper knowledge such as behaviours, motivations, personal characteristics, ambitions and feelings. Such depth of knowledge is not easily replaced overnight.

Organizations can deepen their relationship knowledge by increasing their interaction with the outside world. This may take the form of regular meetings for knowledge exchange and sharing of databases. Toshiba collects comparative data on suppliers ranking 200 quantitative and qualitative factors. It has an active suppliers network where knowledge is shared and suppliers are integrated into future strategies. Extranets provide another way to develop wider linkages. By increasing the number of contacts with key stakeholders, at all levels and functions, you become less vulnerable to the loss of a single contact.

Relationship knowledge can also be deepened by taking a whole range of intercompany interactions to deeper levels of intimacy, and by strengthening knowledge exchange. Relationship marketing, the new vogue in consumer marketing, goes far beyond issuing customers loyalty cards. Customer relationship knowledge comes through exploring mutual interests, seeking new insights through extensive dialogue, and jointly creating new business opportunities. Activities that might previously have been considered confidential to the company are extended to involve stakeholders. These include product planning, marketing campaigns and human resource competency development. Social events also strengthen relationship knowledge. Corporate hospitality does have its benefits!

Knowledge as an asset

The final lever is that of knowledge as an asset. This builds on the notion, mentioned earlier, of measuring and managing intellectual capital. While many organizations have accountants and auditors track in detail every piece of physical plant and machinery, few devote even a fraction of this attention to intellectual capital. Yet this is much more valuable, since it includes knowledge and people.

Advocates of measuring intellectual capital have shown that its measurement provides lead indicators of future financial performance. In his book The New Organizational Wealth Karl Erik Sveiby demonstrates how advertising agency Saatchi and Saatchi, when apparently financially healthy, was rapidly depleting its intellectual capital. This was a precursor of the inevitable decline in its financial fortunes.18 Information, which is arguably the most tangible intellectual asset, rarely gets proper attention. The Hawley Committee in the UK, reporting in 1996, showed a general lack of understanding of the importance of information among boards of directors, let alone having policies or practices for its effective management.19

The starting point of any asset-based approach is that of understanding its different components. Intellectual assets are frequently categorized into the following groups:20

1 Human capital – in the minds of individuals: knowledge, competencies, experience, know-how, etc.

2 Structural capital – ‘that which is left after employees go home for the night’: processes, information systems, databases, etc.

3 Customer capital – customer relationships, brands, trademarks, etc.

In some schemes, such as that of Annie Brooking, intellectual property is separated out as a distinct category.21 This covers assets that are protected by law, and includes trademarks, patents, copyrights, licences and design rights.

Dow Chemical provides a good example of this knowledge lever. In 1994 it had over 29 000 patents in force around the world. However, maintaining the validity of a patent can be costly – up to $250 000 over its lifetime. Dow’s Intellectual Asset Management team developed a comprehensive framework for actively measuring and managing its patent portfolio. It found many patents not being effectively exploited, and others with no obvious ownership. It took measures to exploit patents, either through internal use, licensing or sale, while allowing others to lapse by not paying renewal fees. Within three years the team had generated $125 million in additional revenues, their original target for the year 2000.22

Its very intangibility makes the identification and measurement of intellectual capital difficult. It also defies normal economic rules, thus creating problems for accountants who like dealing with tangibility and precision. Nevertheless, as is shown in Chapter 7, methods for its measurement are evolving. Fortune editor Tom Stewart says: ‘You can’t see it, you can’t touch it, yet it makes you rich’. This lever is surely one that business strategists cannot ignore!

Knowledge processes

As the cases cited so far in this chapter indicate, a wide variety of knowledge-based strategies are found in practice. But beneath this variety, successful initiatives show a degree of consistency in their management of knowledge. This leads to the following practice-focused definition of knowledge management as ‘the explicit and systematic management of vital knowledge and its associated processes of creating, gathering, organizing, diffusion, use and exploitation, in pursuit of organizational objectives’.

The emphasized words are important:

• Explicit – unless something is made explicit it frequently does not get properly managed.

• Systematic – this helps to create consistency of methods and the diffusion of good practice. Systematization also lends itself to automation, leading to additional efficiencies in handling explicit knowledge.

• Vital – every conversation and every new document in an organization adds to the organization’s knowledge pool. Judgement must be applied as to which knowledge is critical and therefore worth managing in a more formalized way.

• Processes – as well as being an important dimension of management and business processes, knowledge processes are important in their own right.

The main processes are knowledge conversion, innovation and sharing.

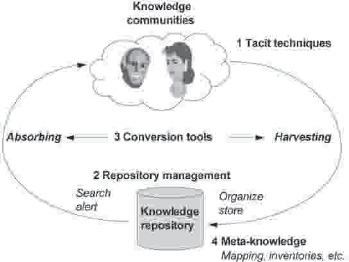

Knowledge conversion

Nonaka and Takeuchi defined four generic processes for converting between tacit and explicit knowledge that they describe as fundamental to creating value:23

Figure 2.5 Different types of knowledge conversion process

• Tacit-to-tacit (socialization) – where individuals acquire new knowledge directly from others, through observation and dialogue.

• Tacit-to-explicit (externalization) – the articulation of knowledge into tangible form through discussion and documentation.

• Explicit-to-explicit (combination) – combining different forms of explicit knowledge, such as that in documents or databases.

• Explicit-to-tacit (internalization) – such as learning by doing, where individuals internalize knowledge from documents into their own body of experience.

Nonaka and Takeuchi describe how these processes interact in a knowledge spiral, with interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge, and where individual knowledge becomes organizational knowledge and vice versa.

Figure 2.5 shows an alternative perspective of some of the processes involved with tacit and explicit knowledge, along with more commonly used terminology. Converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge makes it easier to store, replicate and transmit through computer repositories and networks. When retrieved, it then needs assimilating into another person’s tacit knowledge for application in their specific situation.

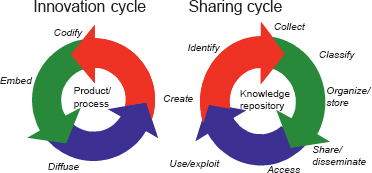

Knowledge cycles

Operating at a higher level than these generic processes are two knowledge cycles that relate directly to the thrusts described earlier – innovation and sharing existing knowledge (Figure 2.6). The innovation cycle on the left represents a progression from idea creation (unstructured knowledge) into more structured and reproducible knowledge, embedded within processes or products. The cycle on the right shows the processes associated with gathering and disseminating existing knowledge, having a knowledge repository as its focal point. Although the activities in each cycle roughly follow the sequences shown, continual iteration through different levels of aggregation means that the actual paths between activities are rather more complex than those depicted.

Figure 2.6 Two value-adding knowledge process cycles

In outline the innovation processes are:

• Create. New ideas are created. Knowledge networking stimulates the cross-fertilization of ideas from different perspectives, and therefore often stimulates an innovation cycle.

• Codify. Here a prototype design or a process description is developed. This embodies the idea into a more transferable form.

• Embed. At this stage the prototype is further refined and its associated knowledge encapsulated in manufacturing processes and organizational procedures.

• Diffuse. Products are distributed in the marketplace or processes are implemented throughout the organization. Their application then generates ideas for improvements, and so the cycle repeats.

In the knowledge-sharing cycle, the knowledge management processes are:

• Collect. Existing knowledge is gathered either on a routine basis or as needed. Often its existence is formally recorded in a knowledge inventory or knowledge map.

• Organize/store. The knowledge is classified and stored, often using an organization- or industry-specific thesaurus or classification schema. This makes subsequent retrieval easier. This process usually involves information professionals or librarians.

• Share/disseminate. Information may be sent routinely to those people who are known to be interested in it – this is information ‘push’. Meetings and events act as vehicles to share tacit knowledge.

• Access. Information is made easily accessible from a database, for example over an intranet. Users access it as they need it – this is information ‘pull’.

• Use/exploit. The knowledge is used as part of a work process. It is refined and developed. Through use, additional knowledge is created and the cycle repeats itself.

A useful form of knowledge that can result from these cycles is metaknowledge – knowledge about knowledge. Thus, some of the most useful Internet or intranet pages are those that hold directories and indexes of what other information is available. Although the processes outlined above are very much geared towards explicit knowledge or information, similar processes take place in the deployment of tacit knowledge, though in a less structured way.

The knowledge opportunity

The two thrusts of knowledge – innovation and sharing – are fundamental foundations for generating business opportunities. Sharing gets the right knowledge to the right people, in the right place, at the right time. It supports decision-making and helps to solve problems using the best available knowledge. Innovation converts knowledge into new products, services or processes. The seven knowledge levers scale up the opportunity, by widening the reach of knowledge. The processes that underpin knowledge practice are the basic building blocks of activity within a knowledge-based enterprise.

As well as following these logical and rational approaches to exploiting knowledge, let us remember that certain characteristics of knowledge mean that the greatest opportunities come from unexpected quarters. These are driven by the power of combination and by the power of community.

The power of combination

Whether knowledge is explicit or tacit, new opportunities can be created by combining different knowledge in different ways. People from diverse backgrounds regularly make connections between apparently disparate ideas. A common technique used in creativity workshops is that of word association. Participants are asked to think of associations between randomly created pairs of words. For example, the objects scissors and telephone in juxtaposition may spark ideas of a cordless phone, a telephone handset that folds open and shut, or simply cut-price telephone calls!

The arithmetic of knowledge is that of multiplication and combination, not addition. From just a few inputs, the number of different ways in which they can be combined increases factorially. With a few basic variants of colour, engine size and trim, Ford can customize over 27 million varieties of the Ford Fiesta. Now apply this arithmetic to knowledge, where there is a wider range of input choices. The number of new ‘knowledge recipes’ is virtually unlimited. Certain combinations will have a value out of all proportion to the value of their original inputs, due to the creative combinations used. For example, the basic ingredients used in cookery have changed little over centuries, but many new dishes are invented every day. This is partly due to the wider variety of input, such as the different varieties of a single vegetable and how it is processed and packaged, but mostly it is due to the creative skills of master chefs.

The drive to innovate through knowledge combinations is also apparent in R&D activities. For example, Du Pont deliberately seeks out collaborative research ventures, and not just for the obvious immediate project. As a result of setting up a collaborative venture with a German university to seek a replacement for CFC in aerosols, not only did it get the replacement propellant as planned, but quite unexpectedly, because different people regularly interacted during the course of this collaboration, it also gained a whole new line of catalysts. The more variety in ideas, people and products, the more likely is an innovative combination likely to arise.

The power of community

The Du Pont example illustrates how knowledge emerges and is taken forward through human knowledge networks. The human dimension adds many more possible knowledge combinations than is possible with discrete knowledge components. Furthermore, human networking brings in a new dimension – the power of community.

One knowledge-enriching practice that is gaining significant attention in knowledge initiatives is that of a ‘Community of Practice’ (CoP). The term emanated out of work at Xerox Parc at the turn of the decade. It refers to a group of people who are ‘peers in the execution of real work. What holds them together is a common sense of purpose and a real need to know what each other knows’.24 They are not a formal team but an informal network, each sharing in Part A common agenda and shared interests. In the Xerox example, they found that a lot of knowledge sharing among copier engineers took place through informal exchanges, often around the water cooler. This happened not because management ordered it, but through individual motivation. The participants developed their own sense of community.

Developing and building knowledge-sharing communities is at the heart of effective knowledge networking. Such communities in the aerospace industry have been found to create better design through sharing and testing of ideas. In Shell participants in a K’MunityTM on deep sea drilling share expertise and contribute to reducing the time to develop new oil wells. Tetrapak Converting Technologies has created learning networks focused on its core technologies, such as packaging.

A related practice is that of knowledge ecology, a term coined by George Pór.25 This extends the community aspect to the wider social context in which knowledge innovation and sharing can flourish. Its core notion is that knowledge is socially contextualized and its development and beneficial application depends as much on building purposeful and committed communities as it does on rational knowledge exchanges. It thus concentrates on the context and environment as much as it does the content. It blends hard (explicit and technical) and soft (social and organizational) aspects of knowledge. It creates flows between conversational knowledge and repository knowledge. Pór makes several distinctions between knowledge management and knowledge ecology (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Contrast of knowledge management and knowledge ecology

Communities exist within and across organizations. Many existed before the knowledge agenda became fashionable. Such communities include quality circles, best practice networks, alumni clubs, professional societies and special interest groups. Although they may not have realized it, they operate as knowledge networks and link hubs of knowledge. The organizational opportunity is to nurture and support such communities, create conditions for new ones to emerge and to harness the knowledge that they generate. As they do so, each community will help grow their organization’s intellectual capital – the knowledge in its people, products and processes, not forgetting relationships and the other strategy levers.

Proven benefits

Progressive companies, such as 3M, Hewlett-Packard and Glaxo Wellcome, have long appreciated the contribution of knowledge to their continued success. Many more have joined them in exploiting the knowledge opportunity.

A good knowledge initiative can achieve a range of benefits, including:

• Avoidance of costly mistakes – The experience of organizations losing knowledge as they have downsized or restructured, has made them more aware of the costs of ‘reinventing the wheel’. General Motors uses debriefing sessions to share lessons more widely through the company.

• Sharing of best practices – Chevron is one of many companies that save millions of dollars a year by taking existing knowledge and applying it to similar situations elsewhere.

• Faster problem-solving – Using videoconferencing, workers at BP-Amoco’s offshore oil platforms can tap into expertise elsewhere in the company when they have problems and minimize production downtime.

• Faster development times – Through learning networks and by linking customer problems to an ideas database, Schlumberger continues to improve its rate of innovation.

• Better customer solutions – Sales and support staff at Buckman Laboratories use K’NetixTM, its computer network, to gain access to the best expertise, and so develop innovative solutions to tricky customer problems.

Examples of knowledge initiatives

• Hoffman La Roche considered the knowledge needed to prepare clinical trials documentation for the approval authorities. By developing knowledge maps, such documentation has contributed to faster time to market for new drugs.

• NEC, the Japanese electronic company, articulated its core knowledge base. This helped it redefine the company’s mission as ‘computers and communications’, markets in which it has shown continuing success.

• Skandia, a Swedish-based insurance company, focuses its management attention on intellectual capital (the knowledge in its people and processes). This focus, with its associated tools, has helped it grow from a small regional company to number five in the world in its market segment.

• Kao, a household and chemical products company, focused on open knowledge sharing among employees. This has helped propel it into new markets.

• PriceWaterhouse created knowledge centres that act as a focal point for knowledge exchange. KnowledgeViewSM provides a repository of best practice for different business processes. This helps its consultants access best global knowledge to provide better solutions to customer problems.

• Hewlett-Packard uses its intranet to share expertise already in the company, but not known to their development teams. This helps it bring new products to market much faster than before.

• Gaining new business – Consultants at ICL use its Café Vik system, to gather scattered knowledge quickly and bid on proposals that would otherwise take too long or cost too much to prepare.

• Improved customer service – By putting solutions to customer problems in a shareable knowledge base, Sun Microsystems has improved its level of customer service. Costs are also reduced since customers can download software corrections over the Internet.

• Reduction of risk – Thomas Miller & Co., a mutual insurer, combines expertise and organizational memory to better understand its underwriting risks.

The challenge ahead

Knowledge, as we have seen, has some unusual characteristics that make its management and exploitation a challenge. Different challenges face organizations, policy-makers and individuals. For organizations, achieving business benefits such as those just described requires new thinking, new organizational structures, new strategies and new practices. Surveys show that the principle barriers are organizational and management, with organizational culture often being the principal issue. Attitudes have to shift from ‘knowledge is power’ to ‘knowledge sharing is power’. Other recurring challenges are those of information overload, lack of time and difficulties of justifying investment. To achieve success in a knowledge initiative, you need to reconcile several opposite pulls. You need to balance the widespread sharing of knowledge without it leaking such that it harms your own interests. You need an environment that stimulates serendipitous tacit knowledge sharing, yet at the same time has some formalization of knowledge processes. You need to develop organizational memory, yet be aware that sometimes it is essential to forget what worked in the past. You need to nurture knowledge networks while retaining some sense of structure and degree of formalization. All are difficult balancing acts.

For individuals, and especially those in traditional management roles, the knowledge agenda poses many personal challenges. You may regard your knowledge as your source of power, and a reason you hold your job. Why should you then share it freely? At school you were probably conditioned that sharing answers to problems was tantamount to cheating, yet that is the very behaviour you are now asked to follow. As managers you were encouraged to seek competitive advantage. Yet successful knowledge strategies require collaboration, perhaps with individuals and companies you regard as your competitors.

For policy-makers, many policies based on industrial age logic will need to be rethought. Economic measures reflect factory output more than they do knowledge creation and exploitation. Industrial policy is more often focused on attracting inward manufacturing investment rather than creating knowledge-based opportunities.

Summary

This chapter has described the role of knowledge in creating value and business benefits. It has introduced some basic concepts of knowledge, particularly the distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge. It outlined the knowledge agenda as two thrusts (innovation and knowledge sharing) and seven strategic levers, including knowledge in products, knowledge in people and knowledge in processes. The key conclusions are that:

• knowledge is pervasive and strategic

• an organization’s most vital knowledge is usually customer knowledge

• most of an organization’s knowledge is tacit knowledge in people’s heads; therefore any knowledge initiative has to motivate and retain knowledge workers

• sharing knowledge, while a cultural challenge, helps increase overall performance

• knowledge in innovation is likely to create even larger long-term benefits

• there are proven business benefits; pioneers have already demonstrated significant bottom-line improvements

• human networking underpins the success of most knowledge initiatives; understanding knowledge networking and how to nurture communities of practice is therefore fundamental.

The knowledge agenda poses a number of challenges, for individuals, organizations and policy-makers. The toolkits in Part C give practical guidance on how to succeed in these challenges.

Points to ponder

1 Do you know off the top of your head the difference in market value and the book value of your organization – in other words the ratio of intellectual capital?

2 Do you know which knowledge is the most vital in your organization – your crown jewels?

3 Do you know who is responsible for maintaining each of these jewels -keeping them up to date, enhancing them?

4 Which of the seven knowledge levers are systematically exploited in your organization?

5 How well do you understand the needs and aspirations of your customers’ customers?

6 Can you find within one minute the name of your organization’s on-the-ground expert on the current political and business climate in Azerbaijan?

7 Do you write up notes of conferences you have attended and circulate them to your colleagues?

8 Do you get reward or recognition for sharing your special expertise or skill with people in other departments and organizational functions?

9 How many people are in your network? How may of these are inside your organization and how many outside?

10 When did you last do a personal inventory of your knowledge assets – your strengths, your specialist knowledge, your unique skills, your information resources, your databases, your network? How valuable is it to you? How do you exploit these assets?

Notes

1 KPMG (1998).The Knowledge Management Annual Survey. KPMG

2 Bacon, F. (c.1598). Religous Mediations: Of Heresies. The Latin original is ‘nam et ipsa scientia potestas est’, literally ‘knowledge itself is power’.

3 See for example Drucker, P. (1988). The coming of the new organization. Harvard Business Review, 66(1), January–February, pp. 45–53; Drucker, P. (1989). The New Realities: In Government and Politics; In Economics and Business; In Society and World View. Harper & Row.

4 Masuda, Y. (1980). The Information Society as Post Industrial Society. Institute for the Information Society, Tokyo; Sveiby, K. E. and Lloyd, T. (1987). Managing Know-How. Bloomsbury; Nonaka, I. (1991). The knowledge-creating company. Harvard Business Review, November-December, pp. 96–104; Stewart, T. A. (1991). Brainpower. Fortune, 3 June, pp. 44–60.

5 Amidon, D. M. (1997). Innovation Strategy for the Knowledge Economy: The Ken Awakening. Butterworth-Heinemann.

6 Garvin, D. (1993). Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, July-August, p. 80.

7 Since a bit is a unit of information, it has been suggested that the corresponding unit of knowledge is a wit!

8 Savage, C. M. (1996). 5th Generation Management: Cocreating through Virtual Enterprising, Dynamic Teaming, and Knowledge Networking. Butterworth-Heinemann.

9 Amidon, D. M. (1997). Innovation Strategy for the Knowledge Economy: The Ken Awakening. Butterworth-Heinemann.

10 Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge Creating Company. Oxford University Press, p.8

11 Polyani, M. (1966). The Tacit Dimension. Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.8

12 Boisot, M. H. (1995). Information Space: A Framework for Learning in Organizations. Routledge.

13 Cleveland, H. (1989). The Knowledge Executive. E. P. Dutton.

14 Oppenheim, C. (1995). Tangling with intangibles. Information World Review, December, p. 54.

15 Johnson, C. (1997). Leveraging knowledge for operational excellence. Journal of Knowledge Management, 1(1), September, pp. 50–5.

16 Amidon, D. M. (1997). Innovation Strategy for the Knowledge Economy: The Ken Awakening. Butterworth-Heinemann.

17 Sources: Hildebrand, C. (1996). Experts for hire. CIO, 15 April, 32–40; also Teltech company literature.

18 Sveiby, K. E. (1997). The New Organizational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Intangible Asset. Berrett Koehler.

19 The Hawley Committee (1995). Information as an Asset: The Board Agendas. KPMG.

20 This model is attributed to a practitioners’ working group that met during 1995–7 and included Gordon Petrash of Dow Chemical, Charles Armstrong of S.A. Armstrong, Leif Edvinsson of Skandia, Hubert Saint-Onge of CIBC, and Patrick Sullivan of The ICM Group.

21 Brooking, A. (1996). Intellectual Captial: Core Asset for the Third Millennium Enterprise. International Thomson Business Press.

22 McConnachie, G. (1997). The management of intellectual assets. Journal of Knowledge Management, 1(1), September, 56–62.

23 Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-Creating Company. Oxford University Press.

24 Seely Brown, J and Solomon Gray, E. (1995). After reengineering: the people are the company. FastCompany, 1(1), 78–82.

25 Pór, G. (1998). Knowledge ecology and communities of practice: emergent twin trends of creating true wealth. Knowledge Summit ‘98, Business Intelligence, London, November. For further information on knowledge ecology see the website of Community Intelligence Labs at http://www.co-i-l.com