Chapter 7

Toolkit for the

knowledge-

based enterprise

The most common question asked of me in my consulting role is ‘how do you get people to share their knowledge?’ Organizational culture is the main stumbling block facing many organizations trying to build a knowledge-based enterprise.

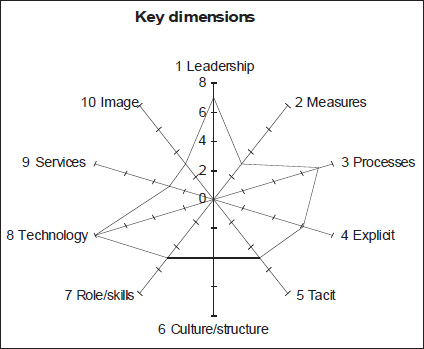

Human and behavioural factors therefore feature heavily throughout this chapter. The guiding framework used is derived from an analysis of factors that underscore the success of a knowledge-based business. Its elements include leadership, environment, culture and structure, processes for managing organizational knowledge, measures, and supporting infrastructures. The activities in this toolkit are sets of questions that preface discussion of each of ten success factors. These help you evaluate how well your organization is implementing the knowledge agenda. Guidance is then given on best practice for each element of the framework.

Leaders and laggards

In order to gain insights into what helps knowledge-based organizations succeed it is instructive to identify differences between leaders and laggards (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 Leaders and laggards in knowledge initiatives

| Leaders | vs | Laggards | |

| 1 | Clearly articulate a vision that incorporates knowledge. | vs | Knowledge is not viewed as a strategic lever, e.g. it is something just for the Information Services (IS) department. |

| 2 | Have enthusiastic knowledge champions who are supported by top management. | vs | Knowledge management activities take place in isolated pockets without strong senior management support. |

| 3 | A holistic perspective that embraces strategic, technological and organizational perspectives. | vs | A narrow process perspective, e.g. limited to knowledge sharing rather than embracing all processes including knowledge creation and innovation. |

| 4 | Use systematic processes and frameworks (the power of visualization). | vs | Follow a standard change process, e.g. BPR, without adding the associated knowledge dimension. |

| 5 | ‘Bet on knowledge’, even when the cost-benefits cannot easily be measured. | vs | Downsize or outsource without realizing what vital knowledge might be lost. |

| 6 | Communicate effectively, both internally and externally. | vs | Disseminate knowledge that is most readily available rather than seek out that which is the most useful. |

| 7 | Interact extensively at all levels with customers and external experts. | vs | Think they ‘know all the answers’, i.e. they are not open to new ideas. |

| 8 | Demonstrate good teamwork, with knowledge team members drawn from many disciplines. | vs | View technology alone as the solution, e.g. ‘it’s in the database’. |

| 9 | A culture of openness and inquisitiveness that stimulates innovation and learning. | vs | Have cultural barriers, perhaps caused by a climate of ‘knowledge is power’. |

| 10 | Incentives, sanctions and personal development programmes to change behaviours. | vs | Get impatient. View knowledge management as a ‘quick fix’, rather than allowing time for new systems and behaviours to become embedded. |

Source: Skyrme, D. J. and Amidon, D. M. (1997). Creating the Knowledge-Based Business, ch. 9. Business Intelligence.

Similar success characteristics occur with innovation. More innovative companies: 1

• make innovation a priority at board level

• continuously review where to focus innovation for maximum business benefit

• have well defined idea management processes that allow ideas and knowledge to be shared, stored and freely accessed

• have a working environment that encourages ideas to flow through the business

• reinforce (through reward systems) management behaviours that encourage innovation

• have a management style that is open, and not closely managed

• empower and trust individuals to initiate change and turn strategy into reality.

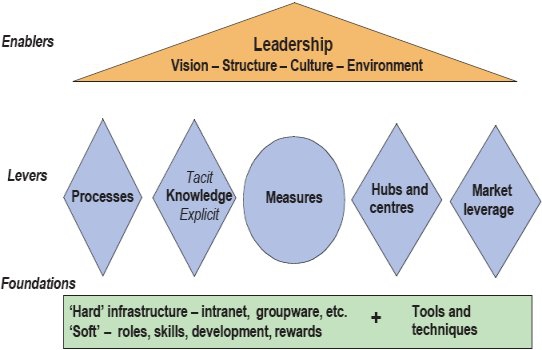

These characteristics indicate that success depends on simultaneously driving and aligning factors across several dimensions. These factors have been drawn together into an action-focused framework for this chapter’s toolkit (Figure 7.1).

At the top layer of the framework are the enablers. Knowledge is seen as strategic and its contribution to the business is clearly articulated. The organization’s structure, culture and environment encourage knowledge development and sharing. Without these enablers most knowledge initiatives drift or stall.

The second layer of the framework comprises a set of levers that amplify the contribution of knowledge. These include knowledge processes that facilitate knowledge flows, knowledge centres that provide faster access to explicit knowledge and better ways of handling tacit knowledge.

Figure 7.1 A knowledge initiative framework

Thirdly, the foundation layer provides the capacity and capability that embeds knowledge into the organization’s infrastructure. It comprises two complementary strands - a ‘hard’ information and communications infrastructure that supports knowledge collaboration, and a ‘soft’ human and organization infrastructure that develops knowledge enhancing roles, skills and behaviours.

The following sections guide you through these layers in turn, covering ten groups of factors in all. Each section starts with a set of five assessment questions. Some have a clear yes or no answer, but you may prefer to grade your answers on a scale of 1–5, e.g.:

0 – Not at all

1 – Considering

2 – Recently introduced

3 – Progressing well

4 – Visible throughout the organization

5 – Making a strong business impact.

Use these individual answers to guide you in developing an overall rating on a scale of 0–10 for each group of five questions.

Knowledge leadership

1 Leadership

• Is there a compelling knowledge vision that is actively followed?

• Is the role of knowledge clearly articulated in organizational mission, objectives and plans?

• Are there clear responsibilities for knowledge strategy and activities, such as through a Chief Knowledge Officer?

• Are knowledge and information treated as vital resources and reviewed regularly at management meetings?

• Do your CEO and senior executives promote knowledge management within their team and to the outside world?

A vision for value

A knowledge-based enterprise needs a solid architecture around which to build its strategies. Most start with a simple effective model that acts as the focal point for its knowledge-enhancing activities. Skandia’s Navigator, for example, uses a visual metaphor of its intellectual capital that guides objective settings. Monsanto’s KMA (Knowledge Management Architecture) is based on a simple schematic that depicts internal and external knowledge, structured/unstructured. Others depict a cycle of knowledge processes, along the lines of Figure 2.6. The best knowledge models are visual, holistic, easily understood and actively promoted. A full architecture will contain many elements and layers, incorporating many of the factors discussed in this chapter. It should be your blueprint for action. But it must remain flexible, ready to accommodate new developments, either externally induced, such as technology, or internal management changes.

Knowledge champions

Knowledge champions promote the benefits of a knowledge-focused approach, and are at the forefront of experimentation. They may emerge from anywhere in the organization, and act as intrapreneurs. They will attract attention to their ideas and ultimately gain support to take them forward. Many knowledge programmes have evolved from the actions of such individuals.

Like any intrapreneur, the life of champions is made difficult in many organizations since they challenge the status quo. They may be unorthodox in their approach, as they seek novel ways of getting things done despite organizational reticence. Their success usually depends on a senior management sponsor or board-level support. Look around your organization and see how well it supports champions of innovation. If it squashes ideas, or reins in the innovators, it is destroying its future.

Knowledge initiatives and teams

The creation of a formal knowledge initiative is usually a starting point for giving an impetus to the knowledge agenda. Early projects within such initiatives are typically best practices databases, expertise profiling (creating so called Yellow Pages), development of a knowledge centre and the implementation of a corporate intranet. Most initiatives are coordinated by one or more knowledge teams. Successful teams draw together people from different backgrounds and disciplines including library science, information technology, human resources, marketing, as well as people with line management experience. Typically they will:

• help businesses formulate strategy for development and exploitation of knowledge – for example, using the seven levers of knowledge discussed in Chapter 2

• Support implementation by introducing knowledge management techniques, such as the processes described in Chapter 2 and later in this chapter

• provide co-ordination for knowledge specialists in various parts of the business

• oversee the development of a knowledge infrastructure, including the development of a knowledge inventory and standards for knowledge asset management

• facilitate and support knowledge communities.

They are the hubs of knowledge about knowledge, with links and nodes throughout the business. At Monsanto, for example, its knowledge team in 1995 had just four full-time staff at its hub, but an extended network of thirty to forty people in business units, who spent 20-30 per cent of their time working with the core team. Bipin Junnarkar, its leader, described the main role of the team as ‘facilitators of the processes of knowledge creation and conversion, and also the cross-pollinating of knowledge across the organization’.

Do you need a Chief Knowledge Officer?

Many organizations are now appointing people with a title such as Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO), often a senior-level appointment, reporting directly to a top level strategy committee or the board of directors. Their role is to promulgate the knowledge agenda and oversee its implementation. They often directly manage the corporate knowledge team. Good CKOs ‘walk the talk’, paint the vision, tell anecdotes and stimulate new knowledge projects.

Is a CKO really necessary? Companies such as Hewlett-Packard have been very successful at knowledge management without one. Its Chief Executive, Lew Platt, actively promotes the strategic role of knowledge, while its decentralized structure and innovative culture allow knowledge initiatives to flourish. On the other hand, many CKOs argue that their appointment has legitimized knowledge management and sends a signal about its importance throughout the organization.

Britton Manasco reflects a growing view of the nature of knowledge leadership: ‘The knowledge leader - or leaders - must become a vital and dynamic force in the organization rather than the figurehead(s) of yet another corporate change program. Eventually leadership must become dispersed and accountability for the success of knowledge initiatives widely held. As I see it, the CKO will have achieved real success when his or her position is no longer necessary.’2

Leading from the top

BP Amoco provides a good exemplar of knowledge leadership. John Browne, its Chief Executive, in an interview published in Harvard Business Review describes learning as ‘at the heart of a company’s ability to adapt to a rapidly changing environment’. He cites learning from partners, contractors, suppliers and customers and of applying the knowledge gained: ‘No matter where the knowledge comes from, the key to reaping a big return is to leverage that knowledge by replicating it throughout the company so that each unit is not learning in isolation and reinventing the wheel again and again’.3

His words are echoed by practical support. The pilot project on virtual teaming described in Chapter 4 was funded to the extent of $12 million, before the full extent of benefits were known. (In fact, it was later estimated that the benefits exceeded $30 million in its first year.) Browne challenges his managers to innovate and to seek breakthroughs. At one oil field five miles offshore, horizontal drilling was used instead of the more conventional artificial island. This saved BP $75 million. Throughout the interview Browne was enthusing about many of the practices described in this book, including learning communities, the free exchange of knowledge, peer groups and not hierarchies. He also stressed that leaders must demonstrate that they are active participants in the learning organization: ‘learning is my job, too’.

Creating a knowledge-enriching environment

2 Culture/structure

• Are project teams deliberately chosen to include people with a wide level of experience, different expertise and age ranges?

• Do personal performance reviews assess and reward individuals for their knowledge contributions?

• Is time for learning, thinking and reflection considered a good investment of time in your organization?

• Do workplace settings encourage interaction and free flow of information, e.g. informal meeting areas, open plan offices, project rooms?

• Are individual experts encouraged to contribute time and expertise to support other teams?

Culture has many definitions, and many facets. It consists of symbols and rituals, attitudes and behaviours, a set of values, yet is largely invisible. It is best described as: ‘the way we do things around here’.4 Throughout our research and consulting practice, culture stands out as the key factor that determines success or otherwise with knowledge management. A knowledge-enriching culture is characterized by:

• an organizational climate of openness

• empowered individuals

• active learning – from customers, from the results of individual’s own actions

• a constant search for improvement and innovation

• intense communications, open and widespread

• organizational slack – time to experiment, reflect and learn

• boundary-crossing – individuals spend as much time interacting with those outside their team as those within it

• encouragement of experimentation, rather than blindly following rules

• aligned goals and performance measures, across departments, teams and individuals

• willingness to share knowledge widely among colleagues, even those in different groups.

3M exhibits the characteristics of such a culture. An important driver of behaviour is the goal that 30 per cent of revenues should be for products less than four years old. This makes people thirsty for knowledge. It aims to attract and keep the right people. According to 3M UK Project Manager, Adam Brand: ‘We back people not projects; it’s better to back good people with so-so projects rather than so-so people with good projects’. He describes 3M as a company of intrapreneurs – ‘dreamers who do.’ Individuals have 15 per cent of their time free to experiment as they please. 3M blends stretching goals, foresight and freedom. Its culture encourages tacit knowledge exchange through person-to-person connections.

In contrast, many organizational cultures put priority on following rules as opposed to acting in the right way. In these organizations ‘knowledge is power’. A Reuters survey found that two out of three managers believe that their bosses and colleagues were ‘information misers’ who ‘value information highly but are protective to the point of withholding it from others’.5

Why don’t people share? Inherently, there is nothing an expert likes doing more than demonstrating their expertise and sharing it with others. Frequently organizations do not encourage them to do so. A culture of sharing can be engendered by creating the right attitudes and behaviours. You can change the style of meetings to encourage dialogue not monologue. You can formally recognize and reward good knowledge practice. Such changes also have to be reinforced by behaviours of senior managers. When British Airways moved to its new head office, Chief Executive, Bob Ayling, went through the same training programme as his staff. He shares the open space with others and has no office of his own.

Siemens’s public networks division had a culture change programme as part of its transformation to a more global and competitive business. It had successive phases that mobilized more and more employees in change and organizational learning. An initial group of thirty-five people participated in an ‘invent the future’ workshop. Each participant then enrolled further people and so the change group grew from thirty-five to 220, then 1000 and then all 9000 in the organization. The programme introduced learning from mistakes, customer awards, friends and family days and communication corners.

Knowledge webs – structures for knowledge innovation

Culture and structure go hand in hand. One reinforces the other. If responsibilities and formal reporting is organized hierarchically, then communication patterns will reinforce it. To encourage lateral communications and boundary crossing, organizational structures must reinforce interdependence through knowledge teams and networks.

Examples of such structures are increasingly found. ABB has over 4000 business units working in a federation. Samsung describes itself as a network of alliances. In 1993 it changed its structure to a ‘network of alliances’. It flattened its hierarchy from seven levels to three, increased teams and networking (‘a clustered web’). In 1997 Monsanto Life Sciences created a ‘honeycomb organization’, where each business unit had two heads - a commercial and science head, and each management team had cross-representation with other teams.

Space – the last frontier?

Many conventional offices are not conducive to knowledge sharing. They have enclosed offices or cubicles that impede communications, or have poorly designed open areas that are distracting. Knowledge networking environments need a mix of ‘caves’ and ‘commons’, i.e. private workspace for intensive thinking or individual work and shared space that enhances interaction. Knowledge sharing is encouraged when offices have more shared space. Thus, 35 per cent of Sun’s Menlo Park office is shared space with 225 different meeting places.6 Better designed offices can reduce space needs by 30 per cent while simultaneously boosting productivity by 30 per cent or more. When Digital redesigned its ‘office of the future’ in Finland, it used a newsroom format with communication hubs and informal areas that had swing chairs. Ricoh’s central research laboratories near Yokohama has its tree of imagination: ‘Imaginative ideas don’t grow on trees. But at the Ricoh Research and Development Centre, they often blossom around one. A giant, 250 year old keyaki tree carved into a star-shaped table, is the center’s creative hub. Around it research staff from around the world meet to exchange ideas.’7

An office conducive for innovation and knowledge exchange is likely to have:

• ‘talk rooms’ or sitting out areas where people can meet informally and converse

• project rooms or ‘whiteboard rooms’ where information is displayed and annotated

• themed areas, such as a ‘pit stop’ or customer area

• easy access to senior executives, who also work in an open informal environment

• main ‘streets’, corridors or hubs that help increase the number of informal encounters.

Scandinavian architects are at the forefront of incorporating these ideas into building design. Waterside, British Airways’ new headquarters near London’s Heathrow Airport was designed by Norwegian Niels Torp to provide open informality and help ‘management on the move’. The overall building is designed as six U-shaped blocks connected by a central street, 175 metres long. Away from the street are quieter, more private areas.8 People can choose where they want to work and plug their portable computers and cordless phones into the telecommunications network. There are many informal meeting areas as well as shops, cafés and a gymnasium.

Managing organizational knowledge

Good organizational knowledge management requires effective mechanisms for each of the processes outlined in the knowledge cycles of Chapter 2. It requires effective sharing and development of integration of both internal and external, explicit and tacit knowledge.

3 The process perspective – systematic and chaordic

• Do you know what is vital knowledge – knowledge that underpins your core business processes?

• Is this knowledge readily accessible and naturally integrated in to the flow of work?

• Processes – does the organization have systematic processes for monitoring external knowledge sources and for gathering and classifying it?

• Are there clear policy guidelines on what is vital proprietary knowledge and needs to be protected?

• Does your organization benchmark its knowledge management activities against other firms and world-class best practice?

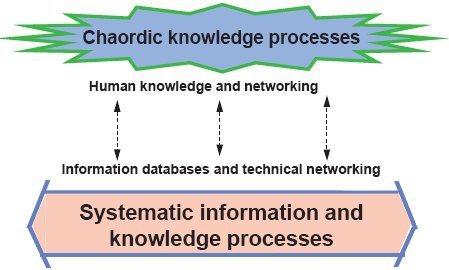

Knowledge is being continuously created in organizations. Explicit knowledge or information lends itself to systematic handling and widespread dissemination, using techniques of information resource management discussed shortly. On the other hand much organizational knowledge is tacit. One study found that managers garner some 70-80 per cent of the information they use in decision-making, not from formal sources but from informal activities, such as meetings and conversations.9 Their decisions are as likely to be based on the opinions and reputation of the informant as they are on the information conveyed. How can such knowledge be better managed?

There are two general approaches to managing tacit knowledge:

1 Converting some of it into a more explicit form, through elicitation and articulation.

2 Creating mechanisms such that informal knowledge exchange can occur when needed.

Hence the challenge of managing organizational knowledge is twofold: that of systematic information management coupled to managing processes which to the outsider may seem chaotic but do have a certain order to them, i.e. they are chaordic (Figure 7.2).10

The first management task is to develop a set of guiding principles within which individual processes can operate. A suggested set is shown below.

Figure 7.2 The knowledge management challenge

Ten principles for better knowledge management

1 Develop clear policies. There should be policies on ownership, maintaining and enhancing knowledge, quality, standards, the management of records and documents throughout their life cycle, and policies on safeguarding information and knowledge against misuse and loss.

2 Conduct and maintain a knowledge inventory. Identify core knowledge, its sources, its flows, it uses. Classify it by its key attributes. Gauge its quality and usefulness.

3 Assign responsibilities. Each important knowledge asset should have named individuals responsible for managing, developing and sharing it.

4 Link knowledge to management processes and business objectives. Make sure that key decision and business processes are supported by highly relevant knowledge.

5 Integrate hard and soft, internal and external. Such juxtaposition helps identify patterns and provide insights.

6 Optimize acquisition and access. Avoid fragmentation of purchasing and duplication of effort.

7 Mine and refine. Extract and synthesize core knowledge, combining the skills of information science, business analysis and editing.

8 Understand the value of your knowledge – both its asset value and value in use. What is its contribution to the bottom line? Consider also the cost of loss, such as key people or of reconstituting databases.

9 Develop and exploit. Continually examine each main knowledge asset and consider how its value could be increased, either for internal use, or external sale or licence.

10 Balance access with security. Protect proprietary knowledge, but not at the expense of inhibiting its development through overprotection.

4 Assessing your explicit knowledge – information resources management

• Is there a readily accessible information and knowledge inventory within your firm, e.g. on an intranet?

• Are the sources of information validated for quality?

• Are your databases, especially textual ones, regularly maintained?

• Are owners and experts regarding specific information databases clearly identified and held responsible for the integrity of the information?

• Do you have a mechanism, e.g. an idea bank, such that ideas not immediately used are not lost for future use?

The key discipline for managing explicit knowledge is information resources management (IRM), defined by ASLIB’s IRM group as: ‘the application of conventional management processes to information, with the aim of maximising its contribution to the achievement of organizational objectives’. A member of this group, Nick Willard, developed a framework for IRM, outlining the five key activities needed in any corporate IRM Programme (Table 7.2).11

Table 7.2 The Willard IRM model

| Identification | What information is there? How is it identified and coded? |

| Ownership | Who is responsible for different information entities and co-ordination? |

| Cost and value | A basis for making judgements on purchase and use |

| Development | Increasing its value or stimulating demand |

| Exploitation | Proactive maximization of value for money |

Good IRM underpins good knowledge management. We now consider some specific IRM activities involved in the knowledge cycles of Figure 2.6.

The knowledge inventory

This helps organizations know what they know. Within IRM the term information audit is frequently used, but this implies compliance. It does however suggest sampling rather than a complete inventory. You need to balance the cost of collating information about knowledge assets against likely benefits.

A typical method is described by Burk and Horton in their book InfoMap.12 Whatever method is used, there are a few guidelines that will make the outcome more worthwhile:

• Start by focusing on business priorities and core processes.

• Sample a representative cross section of the user base - senior management, professionals, different types of job; brief them on the purpose of the inventory and how it will be conducted.

• Confirm the vital knowledge each use needs to perform their key tasks efficiently and effectively.

• Use a range of techniques – surveys, interviews, usage analysis. Intranet search statistics and library access information provide useful hard data.

• Develop lists of knowledge entities. For each entity record its key attributes such as form, subject, content, owner, location, quality, exploitability and where it is used.

• Analyse the flows of knowledge between creators, gatherers and users.

knowledge flows or maps. Matrixes or network diagrams can be used to identify crucial links in the chains of knowledge. Usually what emerge are areas of duplication and gaps. For example, an information audit at one financial institution found twelve different versions of one type of information.

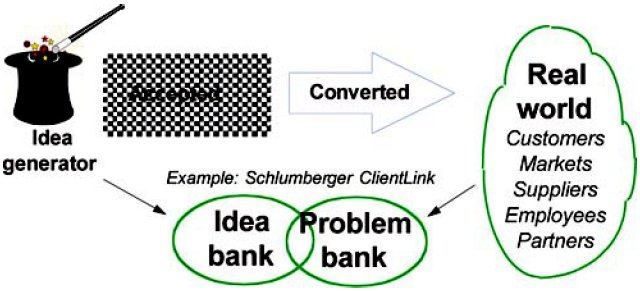

Innovation – the creativity conundrum

The confusion between innovation and creativity was discussed in Chapter 2. The real problem is that organizations do not manage their creative ideas well. What happens to the ninety-nine out of a hundred new product ideas that do not make it through the typical stage gate process to a successful product launch? Mostly they are lost. Yet the ideas might not be bad. It may simply be that at the time they were not technically feasible, there were insufficient investment funds, or market conditions were not appropriate. But conditions change. Therefore a good innovation process will make sure that such ideas are available for future use.

Schlumberger’s ClientLink, for example, matches two databases - an idea bank and a problem bank. Its researchers actively identify client needs and record them on an intranet database in three categories:

1 A solution exists, and there is best practice that can be transferred.

2 There is partial solutions with opportunities and capabilities for tailoring and/or joint development.

3 There is no known solution.

This is then periodically compared with ideas and solutions that other researchers add to the evolving idea bank. Another organization actively encourages individuals throughout the organization to have their ideas more widely exposed. ‘Don’t tell your boss, tell us’ goes the slogan for its idea bank.

Figure 7.3 Capturing creative ideas in an innovation process

5 Tacit knowledge

• Do you know who are your best experts for different knowledge areas?

• Do your knowledge repositories have information that will lead to better tacit knowledge exchange?

• Are important meetings videoed or recorded for later reference and sharing of knowledge?

• Is knowledge captured at the customer interface, e.g. call centres, visits, fed back and used in service improvement?

• Are experts encouraged to convert their tacit knowledge into explicit, e.g. via seminars (videoed), ‘how to’ guides etc.?

Tacit knowledge is difficult to access, since by definition it is in people’s heads. However, you can record explicitly knowledge about where it exists, for example through expertise profiling.

Expertise profiling

Expertise profiling captures information about the expertise and responsibilities of individuals. Most useful are expertise databases that blend some degree of formal structure, such as competencies in defined categories, alongside informal entries kept up to date by the individual. Often referred to as ‘Yellow Pages’, users search by category of knowledge to find relevant individuals and their contact details. Novartis has taken the concept a stage further in its ‘Blue Pages’ which has details of external experts and consultants with whom it has worked. The most difficult challenge is keeping these entries up to date, for example with current projects and activities, since without appropriate culture and rewards, many individuals will rightly ask ‘what’s in it for me?’

Enriching the knowledge repository

As soon as knowledge is expressed explicitly, some of the key features of tacit knowledge are filtered out. It loses contextual richness, the human cognitive dimension and intuitive understanding. That’s why many so-called knowledge bases are really misnamed, since they are databases about knowledge. They can, however, go some way to matching up to their name by adding some element of tacit richness:

• Contextual information - why is this information here? How is it used? What factors need to be considered when using it? Where is it applicable and not applicable?

• Pointers to people - contact details of originators, and links to other experts, e.g. via email hypertext links.

• Addition of multimedia material, e.g. sound clips, extracts of meetings and presentations, a visual demonstration of an entry, such as a team at work. Desktop conferencing also means that information in a database can be used as the object of a tacit knowledge-sharing discussion.

• Associated discussion databases and knowledge communities – places where dialogue can continue.

Knowledge transfer mechanisms

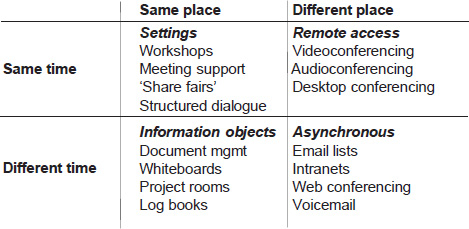

The key to better tacit knowledge transfer is to orchestrate a range of mechanisms that allow personal interaction to take place, in a range of settings. Figure 7.4 shows a range of such mechanisms for both explicit and tacit knowledge.

Figure 7.4 Knowledge transfer mechanisms

Most are self-explanatory. Knowledge ‘share fairs’ however are worth a mention. They act like a marketplace of ideas, bringing those with knowledge into contact with people from business units, or even outside companies, who are potential investors in the much more lengthy process of converting the ideas into prototypes and products. Knowledge providers have posters and ‘stands’ at an exhibition-like setting. They may be accompanied by workshops and other forums for knowledge exchange. They are a good way of bringing researchers into contact with those people who might benefit from it. Hoechst Celanese, for example, has used ‘share fairs’ successfully to find business sponsors for its innovative researchers.

6 Knowledge hubs and centres

• Does your organization have knowledge centres or hubs, where you can find out the best sources of knowledge?

• Can users find what knowledge they need quickly?

• Are your physical holdings – books, periodicals, reports – easily accessible and their key contents searchable on-line?

• Is there systematic monitoring, gathering and classifying of external sources?

• Is your key knowledge indexed and mapped using a clear common taxonomy and classification scheme?

Many organizations are now creating, or rather re-creating, knowledge centres. These are a reinvention and updating of the corporate library, many of which were disbanded or evolved into business units in the early 1990s. A typical knowledge centre:

• knows where to find knowledge, both inside and outside the organization

• catalogues and indexes all types of knowledge asset to aid efficient retrieval

• maintains and sustains the knowledge repository

• integrates hard-copy and on-line information

• provides a one stop shop for multiple knowledge needs

• runs a client advisory service – offering expertise on sources, their availability, relevance, quality and overall usefulness to the business

• helps individuals connect with each other

• offers skills and advice in knowledge management practices

• maintains content standards and provides high level knowledge maps for navigating the corporate intranet.

They are thus a focal point for collection, structuring and disseminating knowledge. This does not mean they do it all themselves. They set the framework and structures, develop guidance and provide information management expertise. A centralized approach offers certain advantages in the handling of information. It offers economies of scale, the pooling of expertise and helps minimize duplication. By acting as a knowledge hub, it also learns how the organization uses knowledge. It can apply this learning by alerting users to new knowledge, connecting people who have problems with those who have potential solutions.

A centre aggregates knowledge that would otherwise be dispersed and lack critical mass. On the other hand, individuals and teams in different locations need rapid access to knowledge. There is, therefore, a case for local knowledge hubs. These can be part of a virtual knowledge centre or network, where each hub specializes and has a physical presence, that provides an access point to the network.

Codifying – the power of taxonomy

Of all the other processes in the knowledge cycle, classification is one of the most powerful, yet the least valued. Even today’s highly sophisticated search and retrieval mechanisms are no match for knowledge structured in a well-designed classification system or taxonomy. Knowledge domains are organized into hierarchies of concepts and related terms. These thesauri help organizations develop a common language and build bridges across disciplines. However, classifying in the context of knowledge management requires a new slant. One primary classification should be by type of use. A division of Siemens, for example, classifies its documents according to a hierarchical problem tree. Users seeking problem diagnosis can therefore systematically work through the symptoms to retrieve relevant information.

Price Waterhouse has used taxonomy to good effect. To contrast best practices across industries, it developed The International Business LanguageSM that maps industry-specific terms against generic business processes in several languages. Users in a given industry can gain new insights by looking at best practice for comparable processes in other industries. Likewise Teltech (page 55) finds its thesaurus invaluable in solving customer problems. In one example, an artificial heart pump manufacturer had spent months trying to solve a leakage problem in a valve. Teltech found an expert from submarine engineering who solved the problem in two weeks. The common connection, achieved through their taxonomy, was pump seals in saline solutions!13

Knowledge hubs at American Management Systems

American Management Systems (AMS), a systems consultancy firm, has fifty-three offices worldwide. Susan Hanley, its knowledge manager, says: ‘my job is to help 7000 consultants leverage their knowledge’. It runs a network of six knowledge centres. The centre acts as a virtual community of expert practitioners throughout AMS. There are seventeen leaders from six core disciplines, 300 associates and eighty support staff whose role is to make a tangible contribution to AMS’s 3000 knowledge bases. There are also videoconferencing facilities at twenty-five different sites. Hanley emphasizes that the centres offer more than a collection of information: ‘they actively and creatively link people’.They provide ‘virtual communities of experts who find and deliver information to client teams’.They operate a ‘hotline’ that consultants call to get access to the centre’s knowledge. It is estimated that the centre saved AMS $5 million in its first year of operation, mainly through faster query handling. On average, the information specialists at the centres can find relevant information and answer questions eight times faster than the typical consultant!

A key ingredient of the success of a centre is that it markets its capabilities well. It should inform and educate potential users. Its staff should get out and meet users. It should host stands at customers’ key internal events such as sales meetings or the in-house annual research conference. It is also important to evaluate the use of the centre and its resources and gain feedback on how it contributes to the business bottom line.

7 Market leverage

• Is information and knowledge readily available in a form that enhances your services to your customers?

• Have you considered reselling your core expertise in ways that will generate new revenue streams?

• Are your services ‘smart’, i.e. customizable and adaptable e.g. by aggregating knowledge from disparate sources?

• Are you known among your clients and peers as exemplars of good knowledge management practice?

• Does your publicity and marketing messages convey the importance and depth of your know-how?

Ultimately, to benefit the organization, knowledge must be exploited externally. This can be in the form of improved products and services or knowledge-based products and services in their own right. Examples were given in Chapter 2. Key methods include publications, on-line information services, adding consulting services, as well as knowledge-enriching existing services.

In every activity where information and knowledge is processed, individuals should be conscious of exploitation opportunities and the need of users. Knowledge is more diffusable and usable in the external world when:

• tacit knowledge is converted to explicit knowledge

• common formats and document templates are used, so that users know where to look for specific items

• it is linked to associated knowledge, e.g. through personal contact details

• it is ‘packaged’ with ‘wrappers’ that define the contents of the package

• it is part of a familiar system or process, such as a customer advisory service

• knowledge carriers, especially people, are easily accessible to explain it.

Thus, even if the marketable knowledge is tacit, it has to be explicitly described to aid marketability. The following list suggests ten ways in which the value of explicit knowledge can be enhanced.

Ten ways to add value to knowledge

1 Timeliness: knowledge is perishable. Different knowledge has different half-lives (‘sell by dates’). Some degrades rapidly.

2 Accessibility: easy to find and retrieve – no long-winded searches, good ‘hits’.

3 Quality and utility: it is accurate, reliable, credible, validated. It is easy to use and can be manipulated to suit specific users and applications.

4 Customized: filtered, targeted, appropriate style and format; needs minimum processing for specified application.

5 Contextualized:Ways of using it are explained. It is enriched by adding some tacit richness (see page I92).

6 Connected: there are many links to related documents and sources.

7 Medium and packaging: the medium is appropriate for portability and ongoing use. It can be reconfigured easily in different packages and reused in different ways.

8 Refined: continually refined by knowledge editors based on feedback from users.

9 Marketed: marketing helps to create demand, thus increasing exposure and use that feeds back into higher quality and additional knowledge.

10 Meta-knowledge: knowledge about knowledge. It is mapped, categorized and its key attributes recorded.

Any knowledge initiative, whether internally or externally focused, can benefit through external publicity. It demonstrates their organization’s seriousness about knowledge to existing and potential customers. Skandia widely publicizes its work on intellectual capital measurement in the form of brochures and CD-ROMs.14 Other organizations find that marketing led campaigns also draw attention internally, and provide a spur for the organization to live up to its external image. Amidon has traced the growing use of marketing slogans that exploit knowledge concepts to gain market leverage.15 More recent examples include:

• ‘With AOL you have the knowledge of 20 million people’ (London Underground poster).

• ‘Them: We hold the knowledge. Deloitte Consulting: We hand over the knowledge’ (Business Week, 7 December I998).

• ‘With M&G, investment knowledge doesn’t come cheap. It’s free’ (Money Observer, February I999).

• ‘Making knowledge work’ (University of Bradford advertisement, June 1998).

The value of knowledge

8 Assessing your measures

• Are the bottom line benefits of knowledge management clearly articulated in terms that all your managers understand?

• Does your organization measure and manage its intellectual capital in a systematic way?

• Do your performance measurement systems explicitly include intangible and knowledge-based measures e.g. customers?

• Do you report regularly on your knowledge assets, such as in supplements to your annual reports?

• Is your measurement system used as a focus for dialogue and learning?

One aspect of measurement that attracts attention is that of justifying investment in knowledge initiatives. Searching for simplistic return on investment (ROI) measures is fraught with difficulties. IDC, for example, cites an ROI of 1000 per cent and more for investment in corporate intranets.16 Eighty per cent of the investment goes on training, content generation and database maintenance, with the remainder on hardware and software. The returns are based on savings in photocopying, document distribution and time spent seeking information. In a series of studies, it found payback periods of just six to eight weeks! In reality these benefits are only realized if time saved by knowledge users is put to good use, which may be hard to prove in the typical case of just 10 minutes a day. The real benefits, though, are not measurable in such simplistic terms. They come through better information, better knowledge connections, better insights and better ‘peripheral vision’, and how they contribute to better decisions and better business performance.

The value proposition

As with many other infrastructure investments, such as email, many of the benefits of knowledge management were not initially anticipated. Few organizations, for example, realize in advance how new communications patterns lead to identification of new business opportunities. Knowledge leaders act first and measure later. They build teams and attract investment without detailed cost-benefit analyses or justification. They have a ‘gut feel’ and are willing to experiment. That does not mean that they do not measure. They do, but retrospectively, once they understand the real impact of knowledge in their business and can articulate the benefits. Their value propositions fall into several groups:

• Knowledge efficiency – e.g. faster access and reuse of knowledge, minimal duplication.

• Business efficiency – e.g. sharing of best practices.

• Business leverage – e.g. better customer service, new product development, innovation.

• Cost and risk avoidance – e.g. reduced rework, fewer loss-making contracts, less risk of knowledge loss or theft.

• Value in intangibles – e.g. improved skills, know-how databases, patents, intellectual property.

Even so, the relationship between cause and effect is complex and often difficult to unravel. For an enlightened knowledge-based enterprise, getting a strategic lead takes priority over worrying too much about detailed justification.

Measuring intellectual capital

While most organizations carry out detailed financial measurement and reporting, few do the same for their intellectual and knowledge assets that are much more valuable. This has led in part to the introduction of non-financial performance measurement systems to guide day to day management actions. Examples are the Balanced Business Scorecard (BBS) and the EFQM (European Foundation for Quality Management) Excellence Model. While these systems give some attention to knowledge related items, such as innovation and learning, they do not explicitly capture knowledge measures. Nor do they help managers identify the underlying cause of different outcomes. The last few years has therefore seen the development of several new measurement systems directly focused on intellectual capital including:17

• The Skandia Navigator (a kind of balanced scorecard) and its underlying value creation model.

• Karl Erik Sveiby’s Intangible Assets Monitor (IAM) - that divides intangible assets into external structure, internal structure and competence of people.

• The Intellectual Capital Index (IC IndexTM), of Intellectual Capital Services. A special feature of this system is that it considers flows of knowledge, e.g. from human capital into structural capital.

• The Inclusive Value Methodology (IVMTM) of Professor Philip M’Pherson. This combines financial and non-financial hierarchies of value. It uses combinatorial mathematics.

The starting point of each of these systems is the identification of the different components that constitute intellectual capital, such as human capital, structural capital and customer capital (see page 58). The number of individual indicators in these categories can be quite high. Edvinsson and Malone list ninety different measures in the five groups of the Skandia Navigator, although in any one unit, only a fraction of these will be used. Measures are of different types – absolute, relative, percentages, ratios, etc. It is also important to distinguish inputs, outputs or outcomes (see Chapter 5). Thus while R&D and IT spend feature as measures in Skandia’s Navigator, better measures may be the actual results of this spending, e.g. number of patents granted, reliability of email service. Sveiby’s IAM is particularly interesting since alongside its main categories of competence, internal structure (processes, systems, etc.) and external structure (customer and stakeholder measures) are subdivisions of stability, efficiency, growth and renewal (Table 7.3).

Table 7.3 Sample indicators in the Intangible Assets Monitor

| External structure | Internal structure | Competence | |

| Growth/renewal | Profit/customer; growth in market share; satisfied customer index | IT investments; R&D investment | No. years education; share of sales from competence-enhancing customers |

| Efficiency | sales per professional; profit per customer | Support staff %; values | Value added/employee |

| Stability | % large companies; devoted customers (repeat orders) | Turnover; ‘rookie’ ratio* | Professional turnover; relative pay |

Note: * percentage of new employees

Even with these measurement systems, it is difficult to give precise numbers that value knowledge. This is because the value of knowledge is context dependent and subjective. Thus IC measurement systems tend to focus on broad measures and direction (e.g. improvement) rather than absolute values. Practical steps to develop and use an IC management system are shown below.

Ten steps to intellectual capital measurement

1 Root the language of knowledge and intellectual capital in the business strategy.

2 Review existing performance measurement systems to see how well they address the intangibles of intellectual capital and knowledge.

3 Develop an appropriate model of intellectual capital, using categories that give balance, and reflect the needs of the organization.

4 Within each unit or team, develop measures within these categories linked to team goals. There should be about three to five per category, say ten to fifteen overall. Involve everybody.

5 Good measures are understandable, practical and predictive. Be approximately right rather than precisely wrong.

6 Integrate these indicators into management goal setting and reporting.

7 Look for some common measures that can be used for comparison across business units.

8 As experience is gained, introduced measures of flow, to help understand time lags, cause and effect, and conversion of human capital into structural capital.

9 Regularly review the measures so that they become part of the learning process of how knowledge supports business strategies.

10 When confidence is gained, start reporting these to external bodies. Drug companies, for example, give details of progress of their R&D pipelines in analysts’ briefings.

Human factors

9 Assessing your ‘soft’ infrastructure

• Have specific knowledge roles been identified and assigned, e.g. knowledge editor, knowledge analyst?

• Is knowledge management considered a core management skill in which every manager and professional has some familiarity?

• Are there individuals in each main group who are responsible for demonstrating good knowledge practice within their group and acting as a coach to others?

• Is your training approach learner centred and does it mesh with the day-to-day activities of the organization?

• Are acquisition of knowledge management competencies and knowledge-sharing behaviours recognized and rewarded?

The human resources function should play a key role in establishing the ‘soft’ infrastructure. In particular, it must:

• Recognize new knowledge roles and skills (see panel), profiling them and integrating them into career structures and plans.

• Create hybrid career paths – legitimate promotion paths that encourage cross-functional moves, job rotation and secondment.

• Develop appropriate recruitment and induction processes, focusing less on jobs and more on transferable knowledge skills and behaviours.

• Enhance learning and development opportunities, so that individuals and teams can continually increase their knowledge.

• Develop appropriate reward and recognition systems, e.g. including knowledge sharing behaviours in performance appraisal and recognizing knowledge skills in skill-based pay arrangements.

Additionally, human resources personnel are usually very prominent as team facilitators and putting in place some key aspects of culture change.

Knowledge roles and skills

• Knowledge analyst – interprets new knowledge in its business and organizational context or translates user needs into knowledge requirements.

• Knowledge broker or connector – links people who need knowledge with those who have it.

• Knowledge editor or synthesizer – reformats conversations, emails and other unstructured knowledge into more structured information.

• Knowledge steward – nurtures and manages knowledge resources; custodian of the knowledge repository.

• Knowledge messenger or gatekeeper – senses the external world, and routes knowledge to where it might be useful; more proactive than the broker who handles specific user requests.

• Knowledge creator – an ideas person, inventor, someone who adds to the organization’s knowledge pool.

Learning organization

Continuous learning is a key component of a knowledge-based organization. Learning is closely related to knowledge. As you learn more, you gain knowledge, which can be applied to gain more learning. A learning organization is one that is committed to learning, both for personal development and the organization as a whole. Learning is recognized and rewarded. Time devoted to thinking and learning is not viewed as wasted time. Organizational learning involves learning from both successes and failures. Practices that are prevalent in a learning organization are:

• Individual learning contracts, based around the needs of the individual and linked to performance and business goals.

• Individuals receive top-up learning budgets to spend as they choose.

• Time is built into meetings to allow for reflection and review.

• Learning takes place on-the-job and when it is needed rather than dictated around course schedules.

• Experienced people coach the less experienced; people new in post are mentored by peers.

• Leadership development: structured learning assignments based on business needs, perhaps in conjunction with external facilitators and institutions.

• Learning is captured as part of organization memory, for example decision diaries that record the results of earlier decisions.

A growing number of organizations are formalizing such practices through a corporate university. Many started by offering courses in conjunction with academic institutions, but are now becoming the focal point for various kinds of learning activity. Anglian Water’s Aqua Universitas, for example, offers participants The Journey, an action-centred learning process. It consists of three parts - orientation, an expedition and review. A typical expedition involves work in the community or installing water supplies in a third world village.

Another facet of the learning organization is reflected in the shift from more formal classroom settings, whether real or virtual, to informal learning networks such as knowledge communities. The networks can also provide virtual classrooms where tutors and students, and student groups do assignments and learn together on-line.

Rewards and recognition

A frequent barrier to better knowledge sharing is an inappropriate reward system. Employees must be motivated to spend time in developing and sharing their knowledge. Many consultancies are now making knowledge contributions part of each person’s annual appraisal and pay award. They review how many ‘thought leadership’ papers were produced, or how many knowledge base entries were created and how well they were used. As was noted in Chapter 5 many knowledge workers value intrinsic rewards as much as monetary ones.

Therefore, various forms of recognition are needed, day in and day out. These include complimenting and praising individuals for their contributions, and giving them opportunities for external visibility and recognition, such as through presentations and publications. Annual awards for knowledge achievement are also motivators.

A more tangible incentive is a stake in the future prosperity of the business. Silicon Valley companies are well known for awarding key employees, but many established organizations seem slow in adjusting to this route. Only recently has IBM opened its stock options beyond a small group of senior executives, thus increasing the number sixfold in two years from 1997.18

Technology, tools and techniques

10 Technology infrastructure

• Can all important information be quickly found by new users on your organization’s intranet?

• Do you use intelligent agents/filters to sift, find and sort key external information that might not normally be available?

• Can people readily share documents and multimedia objects (e.g. video clips) over the internal network?

• Are there discussion forums that support learning networks or communities of practice?

• Is videoconferencing used to connect dispersed locations into regular meetings?

Information and communications technologies can significantly enhance knowledge activities, as demonstrated in Chapter 3. These technologies have maximum benefit when part of a viable collaborative infrastructure that acts as a conduit for knowledge sharing and development. Document management systems, groupware and the intranet are the most commonly found components of such an infrastructure.

An essential element is a collaborative knowledge partnership between the IS function and user departments. Jointly they should investigate the potential of emerging technologies, for example through a technology watch and assessment programme. They should jointly develop a viable knowledge management technical architecture and introduce user-centred applications. They should also act as an exemplar of knowledge management in practice, for example by creating a knowledge base and associated discussion forums to keep the business informed about the practical aspects of choosing and applying the various knowledge technologies.

A viable knowledge information technology architecture

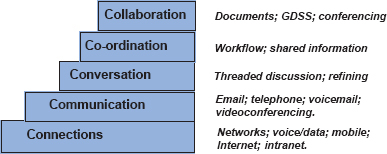

A viable knowledge architecture will cover all aspects of the human-computer interface and supporting services, from physical connectivity to collaborative solutions. Figure 7.5 depicts these in the form of a multilayered architecture, each layer building on the foundation of the ones below.

The base level provides the facilities to connect people whenever and wherever they are - in the office, at remote sites, on the move etc. The next level is provision of basic communications. In many organizations, email has been the technology that has been most significant in enhancing knowledge sharing. The conversation level adds richness and structure to communications. One way is through ‘threading’ messages to show how a dialogue has developed. Co-ordination is provided through facilities such as workflow software or shared information bases. The highest level provides facilities for close collaboration including joint development of documents and the development of knowledge communities through virtual conferencing.

Any architecture must be flexible enough to accommodate the needs of different groups, and to allow for continuous improvement and innovation. This may be achieved by centrally supporting common core elements, while allowing experimentation and local support. Most organizations already have an IT architecture, but many were developed before knowledge management became a strategic priority. It will therefore need to be adapted to accommodate these new needs, which if it was originally designed as flexible, scaleable architecture that takes account of knowledge work and the needs of knowledge workers, should pose few problems. However, this is frequently not the case.

Figure 7.5 A layered knowledge infrastructure

Collaborative knowledge development

Most organizations are only operating effectively at the lower levels of the architecture. They are only scratching the surface at the higher levels. Organizations that have developed their intranets to a fully effective knowledge-sharing and development tool have typically evolved through several phases like those for the Internet (see page 18).

A rich collaborative environment will meld as conversation space and content space (relationships and repositories). Web conferencing tools and knowledge management suites (page 91) are helping this integration. Consideration needs to be given to the interplay between these two spaces (Figure 7.6).

Many companies find that encouragement of personal and informal web pages is one of the fastest ways to grow content and to build knowledge networks. After all, if the individuals are already networking, they will build corresponding links into their personal pages to create dense knowledge webs, thus making it easier for others to enter specialized parts of the network.

Figure 7.6 Collaborative workspaces

Source: George Pór, Community Intelligence Labs (reproduced with permission)

Ten guidelines for creating an effective intranet

1 Link your intranet to key business objectives and processes. Be clear about its purpose and what kind of activities you want it to support.

2 Focus on the user and content. Too many intranet pages are ‘producer-centric’ with pages organized by department. Put in plenty of contact links.

3 Do not focus exclusively on the Web. Use it in conjunction with other tools and applications, including email and computer conferencing and web front-ends to other applications and databases.

4 Provide well-organized information – develop a clear information structure, using a consistent classification system. Provide a map and signposts.

5 Use a clear simple design. Avoid Java and frames unless they really add user value. Don’t overburden with graphics or technical wizardry. Design for maintainability and scalability. This means giving special attention to clusters of information and hierarchies.

6 Make it easy for users to publish. Provide simple to use editors, e.g. exporting from word processors. Provide templates for standard types of information, e.g. expertise profiles, best practice examples, etc.

7 Increase the density of links between different clusters of information - develop reinforcing ‘webs’. Readers will value pointers to other locations with complementary information.

8 Generate opportunities for interaction. Each group of information pages should have an associated discussion database where people can pool their knowledge and further develop the ideas.

9 Employ knowledge editors to continually review and refine information, from other pages and from discussion, and from non-computer based sources.

10 Maintain and sustain it. A programme of systematic updating, based on life expectancy of information, should be part of the organization’s IRM framework.

Such repositories help to being new people up to speed quickly. Schlumberger’s R&D efforts combine technology watch, vision and road maps, portfolio analysis and concurrent engineering. Its ClientLink system (mentioned earlier) connects customer needs to technological solutions. Following the success of its intranet, Schlumberger is using its network to nurture existing communities of practice. It is also borrowing ideas from journalism to improve the communication of knowledge better. However, the essential ingredient on which its distributed R&D effort is built is a solid IT infrastructure, giving instant access from anywhere around the world with high reliability.

Schlumberger - an evolving R&D knowledge network

Schlumberger’s Information Network - SINet - provides a crucial infrastructure for knowledge sharing and development among its many virtual teams. It connects around 25 000 users at 500 locations in over fifty-five countries. One feature that helps knowledge sharing is the large number of shared information repositories, e.g. client and supplier information, site information, project databases, personnel, marketing, clients and business. Project archives are an example of an evolving knowledge repository with project histories, discussion and decisions:

• Plan synopsis – What are we doing? Why are we doing it? Who is the customer?

• Current status – progress reports, milestones, real-time activity, documents

• Future – vision, roadmap, plan

• What we have learned – historical records, reports, results, of which distillation is a key component.

From knowledge management to knowledge leadership

The ten dimensions and fifty assessment questions covered in this chapter provide a useful starting point for evaluating and planning knowledge initiatives. They can easily be adapted to suit specific organizations. Thus, for those selling knowledge services, I tend to expand market leverage into two dimensions – services and promotion, and combine tacit and explicit knowledge into one.

Whichever you use, make sure it is a rounded set that covers hard and soft factors, processes and content, business outcomes and knowledge. Information is typically gathered as a result of a series of workshops or surveys, perhaps as part of a formal review. By plotting your results on a radar chart, you can quickly identify opportunities for improvement (Figure 7.7).

Other starting points for an initiative are to include:

• Make knowledge a key dimension of the annual strategic plan.

• Start with customers – find out how you learn about their current and anticipated needs.

• Perform a strategic review. Create a strategy for knowledge exploitation. Integrate knowledge into business strategies.

• Start with a chronic problem – always a good place to get the thinking caps on.

• Initiate a task force – a common response, but they will need drive and vision.

• Make recording of knowledge needs and sources a step in the business process redesign.

Figure 7.7 A completed knowledge assessment

Wherever you start, you will quickly find that knowledge management is not a stand-alone initiative. It is but one node in a web of strategic activities. It therefore makes sense to identify related initiatives, into which knowledge can be added as a further strand.

Throughout this chapter we have deliberately referred to a knowledge initiative rather than a knowledge management initiative. This is because the term knowledge management is something of an oxymoron, especially where knowledge in people’s heads is concerned. The word ‘management’ suggests custodianship, even control, and a concentration on managing resources that already exist. A better term is knowledge leadership. In contrast to management, ‘leadership’ is about continual development and innovation - of information resources, of individual skills (an important part of the knowledge resource) and of knowledge and learning networks. It embraces both the sharing of what is known, and the innovation of the new - the two thrusts of a knowledge-enhanced strategy.

Summary

The toolkit is an integration of knowledge activities in ten dimensions that cover strategic, technological, human and organizational information and knowledge management factors. In the course of this and preceding chapters a number of practices commonly found in knowledge initiatives have been discussed (Table 7.4).

Table 7.4 Principal practices used in knowledge management

| Creating and discovering | Sharing and learning | Organizing and managing |

| Creativity techniques Data mining Text mining Environment scanning Knowledge elicitation Business simulation Content analysis |

Communities of practice Learning networks Sharing best practice After action reviews Structured dialogue Share fairs Cross-functional teams Decision diaries |

Expertise profiling Knowledge mapping Information audits/inventory IRM (information resources management) Classifying Intranets/groupware Measuring intellectual capital |

This list will evolve as new tools and techniques become more widely accepted. Whatever methods are used, a successful enterprise initiative depends on a balanced approach that:

• focuses on knowledge that is important and used widely throughout the organization

• integrates knowledge as a dimension in existing processes

• integrates and aligns both human and technological systems

• uses a range of mechanisms and technologies, for different types of knowledge transfer

• modifies workplace settings to create opportunities for interaction

• applies IRM skills, so that knowledge is properly classified and mapped

• creates conditions in which knowledge communities can thrive

• ensures that the organization’s culture and human resource policies are supportive of knowledge creation and transfer.

This last point, the cultural challenge, is usually the most difficult. It is best not to be too ambitious. Start a small pilot project and evolve - learning and adding to your knowledge base as you do so.

Agenda for action

1 Apply the diagnostic tool kit in a structured workshop with delegates from different business units.

2 Review your corporate vision and strategic plan to see how knowledge can contribute.

3 Identify the knowledge champions in your organization.

4 Ask each of your senior executives to list four to six specific items of knowledge they need to succeed in their jobs.

5 Review each of your core business processes. What knowledge inputs do they need to be effective? What knowledge do they generate?

6 Print out and display a high-level knowledge map of your company’s intranet. Invite key professionals to identify what they use, and what is missing.

7 Review your senior management’s performance measures. What proportion are aimed at growing the organization’s intellectual capital?

8 Review your organization’s information management policy. Are there policies for ownership, development, exploitation and protection?

9 Do you have a knowledge centre? If so, what are its demonstrable benefits to the business. If you don’t have one, why not?

10 Does your culture support innovation and knowledge sharing? List specific activities that do so and those that inhibit it.

Notes

1 Innovation Research Centre (1998). Annual Innovation Survey. Henley Management College and Coopers & Lybrand.

2 Manasco, B. (1997). Should your company appoint a chief knowledge officer? Knowledge Inc., 2(7), July, 12.

3 Prokesch, S. E. (1997). ‘Unleashing the power of learning’: an interview with John Browne. Harvard Business Review, September–October, p. 147–68.

4 Over 164 definitions were cited in Kroeber, A. L. and Kluckhohn, C. (1952). Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Vintage Books. The definition cited here comes from M. Bower, cited in Deal, T. E. and Kennedy, A. A. (1982). Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life. Addison-Wesley. For a down to earth guide on culture read Williams, A., Dobson, P. and Walters, M. (1989). Changing Culture. Institute of Personnel Management.

5 Reuters Business Information (1996). Dying for Information: A Report on the Effects of Information Overload in the UK and Worldwide. Reuters.

6 Verespej, M. A. (1996). The idea is to talk. Industry Week, 15 April, 28.

7 Advertisement, Ricoh Corporation (1995).

8 The Times (1998). The workplace revolution. Special Supplement, 20 July.

9 McKinnon, S. M. and Bruns, W. J. (1992).The Information Mosaic. Harvard Business School Press.

10 The term chaordic was coined by Dee Hock, founder of Visa, to describe a system that had creative tension between the chaotic and the ordered. There is a Chaordic Alliance website at http://www.chaordic.org

11 Willard, N. (1993). Information resources management. Aslib Information, 21(5), May. The definition comes from Aslib (1993). Working paper -Definitions Task Force. Aslib IRM Network.

12 Burk, C. F. and Horton, F. W. (1998). InfoMap: A Complete Guide to Discovering Corporate Information Resources. Prentice Hall.

13 Michuda, A. (1998). Building a practical framework for knowledge and idea sharing success. Teltech Resources, at Facilitating Corporate Innovation via Knowledge Management conference, ICM, New York, April.

14 It has produced Intellectual Capital Report Supplements to its company reports since 1994. Titles include Visualizing Intellectual Captial, Customer Value and Intelligent Interprising.

15 Amidon, D. M. (1997). Innovation Strategy for the Knowledge Economy: The Ken Awakening. Butterworth-Heinemann.

16 Campbell, I. (1997). The Intranet: Slashing the Cost of Business. IDC.

17 A review of these and other methods will be found in Skyrme, D. (1998). Measuring the Value of Knowledge. Business Intelligence. The Skandia Navigator is described in Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M. S. (1997). Intellectual Capital. HarperBusiness. IC Index is described in Roos, J., Roos, G., Edvinsson, L. and Dragonetti, N. (1997). Intellectual Capital: Navigating in the New Business Landscape. Macmillan. The Intangible Assets Monitor is described in Sveiby, K. E. (1997). The New Organizational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge-Based Assets. Berrett Koehler.

18 Sanger, I. (1998). Stock options: Lou takes a cue from Silicon Valley. Business Week, 30 March, p. 34.