Chapter 8

The interprise

toolkit

No enterprise is an island. It depends on the active support of customers, suppliers, employees and many other stakeholders for its continued success. Collaboration is inevitable. It is needed to bolster innovation and meet diverse needs. Collaboration with competitors is also frequently needed. Thus, many embryonic markets will remain small and fragmented until manufacturers agree common standards. Collaboration takes many forms such as supplier–customer partnerships, strategic alliances, informal co-operative marketing and, of course, virtual corporations.

What does it take to create a successful interprise – a collaborative venture comprising several enterprises? Who makes suitable partners? How can inter-enterprise knowledge networks be created and sustained? Whether your enterprise is large or small, this chapter takes you through a series of steps that addresses these challenges.

Collaboration knowledges

Before you can start to build a successful collaborative interprise, you need a set of basic knowledges – the know-why, know-what, know-who and know-how of interprising.

Know-why: the interprising advantage

There are many reasons to seek collaboration and partnership with other organizations, such as those listed in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1 Benefits of inter-enterprise collaboration

| Resource efficiency | Market development |

|

Economies of scale – sharing resources Reduced investment costs through sharing Flexibility of resource allocation Access to specialist skills Better deployment of your own skills and assets Access to technical resources, licences Reduction of risk for investment |

Innovation Faster time to market Flexibility of response Addressing needs of larger customers Meeting more complex requirements Broadening product portfolio Access to non-traditional markets Access to new channels Denying unique resources to a competitor Increased geographic coverage |

The first group of benefits involves pooling of resources to increase efficiency and reduce duplication. An example of this is the LearnShare alliance, a consortium of non-competing technology organizations (including 3M, Deere, Motorola, Owens-Illinois and Warner-Lambert), who pool their training materials and resources. It was found that 76 per cent of their internal training needs were identical and that they were duplicating effort.

The second group of benefits increases market leverage, and is particularly beneficial for smaller organizations and the self-employed who by themselves do not have a complete range of skills to meet customer needs. By creating a virtual organization, they can combine competencies and other resources, to meet specific customer needs. SciNet is a virtual biotech company, based in Brauschweig, Northern Germany. It develops, manufactures and markets bioactive proteins to speciality chemical and pharmaceutical companies. Its network of 300 members includes scientists, engineering, project management, industry experts and lawyers. SciNet manages projects by bringing together the necessary expertise from its membership network.

Activity 8.1: Examine your motives for collaboration

• Are you facing an external threat e.g. regulatory or a dominant competitor, where several players in the industry need to develop a concerted strategy?

• Do your customers have needs that are not being met? Are they demanding more than you alone can deliver, quicker?

• Do you have unrealized ambitions that you cannot fulfil due to lack of resources and skills?

• Is there over-capacity in your market that is resulting in duplication of effort?

• Are there investments you would like to make but are too large or risky?

In seeking collaboration, your main aim is to address situations and create new opportunities that would be impossible to do by yourself.

Know-what: structures and forms

There are many types of collaboration. They may be formal or informal, stable or dynamic, close or loose, involve two parties or many. In the multiple-partner situation there may be a co-ordinating hub, such as a trade association or network broker, or a network of equals. Table 8.2 identifies some of these forms. The various forms are not mutually exclusive. Many large companies enter many different arrangements, each for a specific purpose.

Interactions between enterprises range from a straightforward trading relationship to complex knowledge networking. Knowledge relationships are also very varied. Some are based around pooled knowledge sharing. A trade association, for example, may co-ordinate members’ sales statistics, providing aggregated information and making individual submissions anonymous. More in-depth relationships involve collaborative knowledge development. Here, interactions are unstructured, evolving, and depend on high levels of communications and trust.

Activity 8.2: Knowledge of structures

Review the various types of collaboration (Table 8.2) in which your enterprise is already participating. Which are the more and less successful? Can you explain why? What are their advantages and disadvantages for your organization, bearing in mind its strategic intent?

When considering a new collaboration:

1 What knowledge will be exchanged?

2 What will be jointly developed?

3 How can it be exploited?

4 Who owns the collaborative knowledge?

5 What are the ownership and exploitation rights?

Table 8.2 Different types of interorganizational structures

| Structural arrangement | Types of collaboration | Typical characteristics – knowledge considerations |

| One to one | Joint venture; strategic alliance; cross licensing; co-operative marketing; subcontracting | Bipartite interactions. Often explicit agreements about resource exchange and ownership of jointly developed intellectual property. |

| Multiple – central co-ordination | Supply chain network; trade association; trusted third party*; business network with broker; expert networks; special interest forums | Some have a dominant partner, who dictates the rules for participants. Others have steering bodies and committees that represent the interests of all members. The co-ordinating authority acts like a knowledge hub, and may well have a knowledge advantage over individual participants. |

| Multiple – self-managed | Consortium; co-operative; dynamic business networks; virtual corporation | A network of peers offering complementary resources and knowledge. May start with less formality than other arrangements that could lead to disputes over intellectual capital, unless addressed in a timely fashion. |

Note: * Trusted third parties are found in electronic commerce networks, where an intermediary, such as a bank holds confidential information that neither party wants to reveal to the other.

Another overlay is that many knowledge networks, such as professional associations, straddle enterprise boundaries. So while enterprise boundaries delineate formal commercial and legal entities, they are permeable to knowledge. This creates challenges in a knowledge networking environment, where new forms of boundary are constantly being drawn and redrawn.

What kind of arrangements should you enter? The short answer is as many as you need to achieve your aims, bearing in mind that each and every collaboration will take valuable management time to work successfully.

Figure 8.1 Factors for partner selection

Know-who: selecting partners

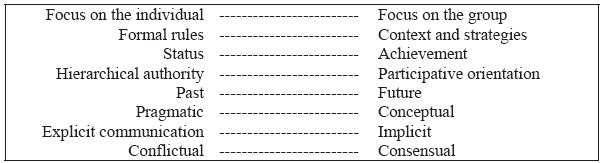

Selecting the right business partner is as much about culture and personality as about other attributes. Sometimes you may appear to have little choice of partner – they are trading with you as customers or are a unique and critical cog in your value system. However, you should consider how closely you want to work with them in the long term and whether other partners are, or could emerge, as more suitable.

Successful partners share mutual interests, offer complementary competencies, and have compatible (though not necessarily identical) cultures (Figure 8.1). Good collaborative partnerships create something new for each party. They harmonize different organizational perspectives and have balanced relationships where no single partner is dominant.

Activity 8.3: Finding suitable partners

• Are there organizations with whom you already have good working relationships?

• Are there organizations in other fields, but who have competencies you need, that you secretly admire?

• Are there natural partners in your supply chains (e.g. suppliers, customers) offering complementary products or services?

• For each potential partner: do you know their key competencies, their motivation and key strengths and weaknesses?

• Consider developing a knowledge base, which holds such information on potential partners.

Various business networks offer a pre-qualification stage before more formal partnering. Typically, their member organizations have demonstrated their credentials and distinctive competencies. The network promotes the members, and they promote the network.

A common characteristic among collaborating companies is that they are simultaneously customers and competitors. This does not matter, as long as individuals working in each enterprise know which role applies when and where. It may be necessary to create so-called Chinese walls, where knowledge from one part of the business is deliberately withheld from another part playing a different role.

Know-how: a framework for collaboration

There are several models of collaboration development, most based on finding strategic fit and cultural compatibility.1 The marriage metaphor is frequently used. Larraine Segil lists elements that make for harmony in both regimes – compatibility, commitment, sharing. She reminds us that in both domestic life and strategic alliances the failure rate is high – as much as 60 per cent in the first five years. This is one reason why some of the best collaborations prepare plans for an orderly dissolution, akin to a prenuptial divorce settlement. She describes an approach based on check lists and guidelines for diagnosing your enterprise personality, the stage of the enterprise life cycle, and the relative importance of each enterprising joint venture.2

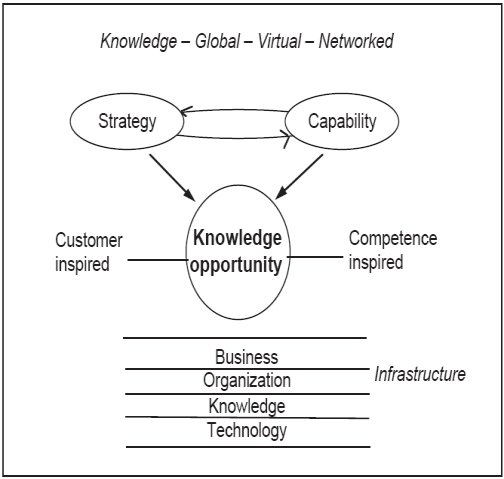

Our perspective here extends to virtual collaboration to generate opportunities based on knowledge. There are two good sources of such an opportunity - the customer interface and combinations of distinctive competencies, which are themselves influenced by collective strategies and capabilities (Figure 8.2). Also essential to any long-term collaboration is a set of infrastructures to sustain the jointly developed intellectual capital. These elements provide a framework to guide us through the rest of the chapter.

Figure 8.2 A framework for collaboration

Knowledge collaboration

Innovating with customers

Despite its importance customer knowledge is only superficially tapped by most organizations. Debra Amidon, who has explored customer knowledge in some depth writes about Innovating with CustomersSM:

Customers have always been integral to the innovation process. What else is the purpose of productization and commercialization? However, current global business conditions have shed a new light on the value of customer interaction and the scope and structure of the innovation process itself. Moreover, what good are your customers if they are satisfied, and not successful?3

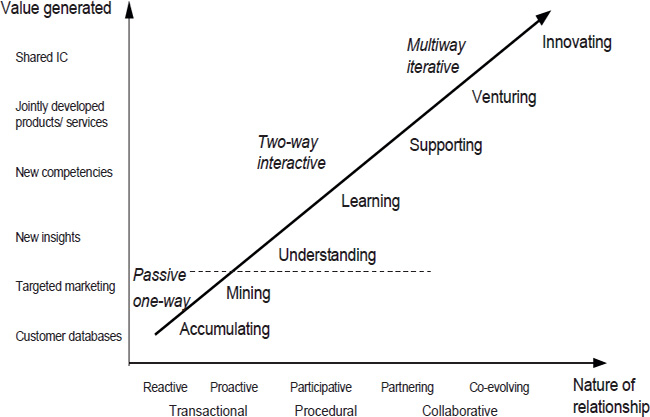

She explains that the biggest opportunity lies in the development of new products and services to fulfil unarticulated customer needs and unserved markets. Developing a relationship that achieves this means moving beyond a purely transactional relationship to intense dialogue and full partnering (Figure 8.3). As the relationship progresses through these transitions deeper levels of knowledge are shared and created, resulting in new and larger sources of value.

Figure 8.3 The customer relationship spectrum Source:

Adapted from Amidon (I997)4

The higher levels of partnering represent the development of two-way customer knowledge channels that go way beyond market research. The classic example is that of the Sony Walkman. Sony’s market research implied that the innovative combination of personal headphones and portable tape recorders would not sell. But Akio Morita, head of Sony, sensed there was a need: ‘In New York, even in Tokyo, I had seen people with big players and radios perched on their shoulders blaring out music’.5 Tools and techniques to deploy along the customer relationship spectrum include:

• Data mining and business modelling – are there correlations with purchasing patterns that give new insights into your customers’ behaviour?

• Individual customer interviews and visits - finding out about your company and products in the customer’s context. Product managers and engineers can often develop a rapport with customers that is not normally possible with a salesperson merely intent on selling products.

• Focus groups – representatives from several customer groups explore in some depth a particular issue.

• Inviting customers into your in-house marketing or product development meetings. This means overcoming the psychological hurdle of ‘washing your dirty linen in public before getting your act together’. But if you can do this you have got past barriers of creating more openness.

• Creating joint development teams. This allows true collaboration in pursuit of product improvement or tackling a difficult customer problem.

Activity 8.4: Deepening your customer knowledge

How well do you know the business plan of your key customers?

How can your products or service help them pursue new opportunities?

• How well do you know your customers’ customers?

• What are your standards of customer performance? How well do they mesh with your customers. Can you integrate them more closely?

• What are your customers’ core competencies and technologies? Is there a joint opportunity for exploitation?

• What learning environments do you share? Can more be done together to broaden the range of knowledge sharing?

Your focus must be on your customer’s success. At its simplest this means customizing your standard product to specific needs. More in depth collaboration will go further and address the needs of the customer’s customer. Steelcase, a supplier of office furniture, is a good example of this. It works with a network that includes architects, end-users and hotel operators. Typical results of this in-depth dialogue are new opportunities with a hotel chain to meet the needs of the peripatetic professional that also involved computer manufacturers and telecommunication service providers to make it successful.

Collaborative knowledge venturing

The second main source of knowledge opportunity comes through combining complementary competencies. Here, organizations collaborate without at first knowing in detail what outcomes they are seeking. Nevertheless, they will have some mutually compatible high level objectives such as developing products for an emerging new market.

The initial reason for networking and collaborating may arise from a specific need, but after that need has been met, ongoing collaboration may generate new opportunities unforeseen by any party at the outset. For example, Du Pont has several collaborations with universities. The main reason for collaborating is to mix expertise and capabilities within a broad programme of work. One such collaboration, initially instigated to develop a CFC replacement in aerosols, resulted in a new line of polymers. This outcome was never expected or designed in at the outset. It emerged from an idea by a university researcher that was later refined through continual dialogue with Du Pont as an existing collaborative partner.

Activity 8.5: Creating collaborative networks

• Explore your supply chain - from suppliers to ultimate consumer. Are there organizations within it whose competencies and culture would make natural innovation partners?

• Are there events or forums you have attended that included people from outside your industry, where you would like to continue exploring opportunities?

• Are there existing collaboration partners with whom you have good rapport, but which are narrowly focused, where a day or two of brainstorming might identify some new co-operative activities?

Such collaboration calls for teams from different organizations to network together regularly in various knowledge-sharing projects and forums, such as innovation workshops. As with teams, diversity is important. An ideal collaborative network would include companies close to consumers and those further back in the supply chain. It would include product, project and service companies, and relate to a particular type of consumer need. Thus a food chain cluster might include a retailer, a food manufacturer, an agrochemical company, as well as an airline, a hotel, a telecommunications provider and a bank. As specific projects emerge, virtual organizations are formed and the network evolves to provide a rounded set of competencies needed.

Exploiting virtual knowledge space

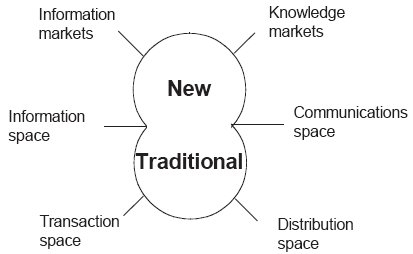

Many of today’s innovative organizations exploit the advantages of the Internet. Chapters 2 and 4 give several such examples. One framework for exploring the possibilities more systematically is Albert Angehrn’s ICDT model. The ICDT model portrays four virtual spaces (Information, Communications, Distribution, Transaction) in which to develop new opportunities from traditional markets (bottom segment of diagram). To this basic model, two spaces representing new information and knowledge markets have been added to provide a more complete framework (Figure 8.4).

Angehrn cites the strategic value of the Internet as its ability to enhance linkages over distance. Core competencies in this environment include the ability to move and integrate information and knowledge quickly. Speed is of the essence: ‘Speed in detecting markets, in the first place. Speed in finding out which are the required resources and where they lie.

Figure 8.4 Sources of virtual knowledge opportunities

Source: Adapted from the ICDT Model of Albert Angehrn6

Speed in internalising them and combining them with existing competencies. And ultimately, speed in exploiting markets before competitors acquire similar competencies. Here again, the Internet promises to be a powerful weapon.’7 His language reflects the competitive paradigm, and as written applies to a single enterprise. However, we can extend his ideas and apply the model of Figure 8.4 to collaborative opportunities:

• Virtual transaction space (VTS) – where transactions take place. Look for collaborative opportunities with providers of payment services, or virtual locations, which have the pull to attract your potential customers.

• Virtual distribution space (VDS) – channels for distribution of digitally encoded goods. Look for co-operation with high-volume or specialist distributors of software, books, information bases etc. Can they help you expand your markets by offering samples?

• Virtual communications space (VCS) – where interaction takes place. Are there natural communities that attract your target customers? Can you identify opportunities for collaboration to meet unmet needs expressed in these communities? Network with potential collaborators in closed user groups to discuss trends, opportunities and common issues.

• Virtual information space (VIS) – the place for visibility. Are there relationships you can develop with those who organize information, such as directory providers or on-line magazines? Consider a specialized portal site that adds value through aggregation and customization. Seek collaborators who can contribute and do local language or national variants.

• Virtual information markets (VIM) – integrated spaces where all phases of an information purchase are addressed. Work with database providers, media and software companies to collaborate with you and industry peers in creating niche markets based around unique information resources.

• Virtual knowledge markets (VKM). These extend beyond information to fully interactive knowledge sharing. Expert networks are an example of this. Look for collaborators with complementary expertise that could offer on-line advice or services for knowledge communities. There are also opportunities for market makers who connect providers of knowledge with users.

Each space is a hotbed of entrepreneurial activity with new players emerging who act as intermediaries to a large number of different companies and industries. What they often lack is content. Thus, there are many unexploited opportunities in working with others to provide a virtual ‘one stop shop’ of information and knowledge for a cluster of related customer needs. Throughout virtual space, there are opportunities for collaboration, mutual linking and web building that are impossible in physical space. As electronic commerce in traditional goods grows, virtual knowledge markets are the new wave of collaborative opportunity.

Activity 8.6: Collaborative exploitation of virtual knowledge space

• What customer knowledge can be extracted from existing or new virtual spaces? Can you create a community that draws in your customers to share knowledge of your product applications?

• Are there established or emerging players who provide global virtual spaces for your industry and customer groups? If so, how can you collaborate with them? If not, who are the natural collaborators to develop such information and knowledge spaces?

Organizing collaboration

Strategic fit

The starting point of a successful collaboration is strategic fit - how complementary the business strategies of the two organizations are. A useful way of assessing this is by mapping the strategic dimensions of your industry. Figure 8.5 shows a generic template from which industry or market specific templates can be derived.

By comparing your own coverage and that of your potential collaborators, the degree of strategic fit can be determined. Generally you are looking for complementarity. However, the closer the relationship is expected to develop, some overlap is desirable, especially in terms of customer groups served. This will generate efficiency savings. Your overall aim should be to cover the strategically important parts of the chart that are beyond your own immediate capabilities. It is also important to consider the wider business context. How are political, regulatory, economic and social trends affecting your industry and potential collaborators? Will they affect certain combinations differently to others?

Figure 8.5 Strategic fit template

Activity 8.7: Determining strategic fit

Draw up a specific template for your key businesses, using the language of your industry. Add or subtract dimensions (rows) as appropriate. Using separate acetate overlays for your own firm and potential collaborators, colour individual blocks according to the level of coverage or market penetration. Use different shades for intensity and different colours for different firms. See which combinations of collaboration make the most strategic sense.

Competence matching

Complementary competencies are an integral part of knowledge-based collaboration. As well as knowledge of the different strategic domains, consider also each partner’s contribution in terms of:

• age profiles – does the combination produce a balanced age range?

• key tasks – knowledge and skills for the key activities of the interprise

• process expertise – what key process knowledge does each party contribute?

• core functions – who provides strength in research, manufacturing, marketing, sales, service etc.?

• support functions – who will provide services such as IT, human resources, legal?

• core competencies – what are the unique skills of each partner? What and who will be contributed?

• key assets and resources – offices, equipment, intellectual property etc.

The strengths and weaknesses in each of these areas should be reviewed. Each party has to be clear what is in the organization as a whole, and what is accessible to the network or collaborative relationship. Compatibility is more than just complementarity. It involves some commonality in approach and outlook. Alliances of very similar or totally unrelated competencies are unlikely to succeed. In addition to general competence matching, Lorange and Roos8 identify three critical competencies needed in alliance building and development. The first is political, managing the interprise’s different stakeholders. The second is entrepreneurial, knowing how to enable people from different organizations to work together effectively. The third is analytical, the ability to carry out specific investigations, such as those suggested in these activities.

Activity 8.8: Mapping alliance competency profiles

• Map the competencies of collaborators in your existing alliances. (Use bubble charts or templates.) Is there a pattern in those that are successful and those that are not?

• Develop a map of the key competencies needed in your planned new interprise. Show the relative strengths of each potential partner. List them and show how they contribute to the combined vision and strategy. Identify differences and determine how they can be worked through or overcome.

Cultural compatibility

Cultural incompatibility between partners is a primary reason why many collaborations fail. Cultural differences do not necessarily mean failure. In general cultures that are organic, achievement or person oriented and outward looking are more mutually compatible, but clash with cultures that are mechanistic, rule bound, bureaucratic or hierarchical. In cross-border partnerships, the power-distance dimension of Hofstede is the one that needs to be most compatible.

A useful diagnostic tool has been developed as part of the EU’s Innovation Programme.9 This programme encourages collaboration across both organizational and national boundaries, where overcoming cultural problems is a major consideration. The tool helps project participants understand the key dimensions of their own culture and management styles and draws out orientations in eight dimensions (Figure 8.6).

More important that any particular cultural differences is cultural rigidity. Use of such a diagnostic tool allows interprise participants to explore their differences and consider ways of adapting to mutually accepting working norms. The interprise culture can either be a fused new culture, a transition from one to the other or separate team cultures that know how to work with each other. Perhaps the most important cultural trait is the willingness to co-operate and wholeheartedly support the collaborative venture.

Figure 8.6 Dimensions of culture (from EU Innovation Culture Diagnostic)

Activity 8.9: Exploring culture compatibility

Share with your partners your key values and elements of your organization’s culture. If possible, use a common diagnostic instrument and compare differences. Discuss the values and kind of culture that you feel would be appropriate for your collaborative venture. Use principles 6-15 of Chapter 6 to help you define your values.

Building the virtual organization

Any collaborative venture will need to go through many of the activities described for teams in Chapter 6. Here we consider the particular case of building a virtual organization, a joint venture of several organizations, typically geographically dispersed. A starting point of a growing number of virtual organizations is a loosely connected business network from which different virtual organizations can be formed as needed.

Business networks

A key feature of networks is that they constantly change. Today’s clusters and close connections may not be tomorrow’s. A network offers a more fluid arrangement than formal long-term alliances. Individual members can readjust their position in the network as their interests and those of the network as a whole evolve.

Business networking is most developed in Denmark, as a result of a national enterprise initiative in the late 1980s to help smaller enterprises collaborate.10 The programme has three main elements - a network support infrastructure, network brokers and the creation of individual networks or virtual organizations. The programme is described more fully in Chapter 9. The evolution phases in the Danish model are:11

1 A business network creates awareness of its capabilities and network broker competencies for a specific business sector. It analyses its members competencies and identifies potential joint opportunities. Potential partners who can plug competency gaps are also identified.

2 Validation of core idea and network competence. A strategic analysis and a feasibility study of network opportunities are carried out. At this stage, confidentiality agreements are drawn up between members and the broker.

3 A network business plan. This determines funding for network activities and assigns responsibilities. The terms of co-operation are finalized, and the necessary legal entities created.

4 The network process of building and launch. This puts in place core processes and necessary infrastructures.

A key feature of the Danish model is the network broker. A broker acts as a facilitator to bring network members together. An example of the Danish model in the UK is that of the Campbell, Hare and Jenkins network. This combined the competencies of a printing shop, a translation service and a computer graphic house in south-west England. The partners did not previously know each other and were brought together by a network broker in 1994. In combination they were able to offer clients a complete service in producing technical product publications in foreign languages.

Perhaps more common than the formal broker role is the natural evolution of informal business networks. Members may meet occasionally to exchange information, while clusters of members form closer associations where interests and opportunities coincide. However, they can still benefit by explicitly carrying out brokering tasks, such as defining capabilities. This provides pre-qualification and can save valuable time when setting up an individual virtual project or organization.

Activity 8.10: Know your business network

List enterprises with which you have developed more than a casual relationship. Now provide an overview of their competencies, their strategic intent and what constitutes an ideal opportunity to work together. Is this information kept as organizational knowledge and regularly updated when individuals from the two enterprises meet?

Network analysis

Network analysis techniques provide more sophisticated ways of tracking emerging clusters in your industry and those organizations who may or may not make potential virtual organization partners. A good example of this is an analysis by Valdis Krebs of alliance activity for the main actors in the Internet marketplace. Two primary measures were used -level of activity and reach, i.e. the number of steps to reach others. Using the network analysis package Xsite, he found that Netscape and Microsoft were two key relationship hubs. They each had joint agreements with a third of other Internet participants.12 Krebs also found that of fifty-nine linkages, just five organizations had links to both Netscape and Microsoft, the two cluster hubs. These ‘boundary spanners’ have a unique view of both clusters, and are pivotal knowledge points. As Krebs notes they are ‘the shortest path between two arch competitors’, and thus care is needed as to what knowledge flows through them.

Another form of analysis is that used by the Agility Forum. It uses Dooley graphs to show the interactions and process loops between different members in a virtual organization. Some are one-to-one interactions, while others involve interactions that ripple through the network.13 Factors analysed in a process are the number of nodes and loops, the lengths of paths and time delays. This analysis determines the time it takes to make decisions or modify inter-enterprise processes.

Such analyses can reveal the nature of knowledge flows and provide insights into critical knowledge areas that depend on high degrees of trust or high degrees of responsiveness.

Collaboration contracts

At some stage, usually when resources are committed or confidential knowledge is exchanged, formal contracts are needed. However, collaborating partners can do much useful preparation before involving lawyers by thinking through the topics that such an agreement will cover.

There are several other legal and regulatory matters that may fall outside the scope of formal agreements but should nevertheless be addressed. One is that of labour agreements for the interprise, especially if the working conditions and pay scales of each partner are different. Irrespective of formal agreements, the ultimate success of collaboration depends on trust and working well together. Those who focus too early on contractual arrangements will miss out on relationship building and opportunity development.

Topics for a virtual organization agreement

• Purpose – the reason why each partner is entering the contract.

• Exchange – what is exchanged, what each partner gives and expects in return; obligations and rights.

• Identity – how the virtual organization is represented to the outside world.

• Key personnel – roles and responsibilities in the venture; named people where critical.

• Key working processes – budgeting, planning, work allocation, execution of projects.

• Information and knowledge exchange – ownership, intellectual proprietary rights, ownership of new knowledge.

• Commercial arrangements – valuing contributions and assets, sharing of costs and revenues, responsibilities for liabilities.

• Monitoring and enforcement – changing priorities, adjustment, adjudication.

• Dispute resolution – procedures, independent arbitrators.

• Dissolution or restructuring – how members can leave and others join. Sharing of assets on dissolution.

Implementing the infrastructure

Sustaining an interprise over any length of time requires the implementation of an interprise infrastructure, independent of its members, although shared by them. The infrastructure supports the modus operandi of the interprise along four key dimensions – business processes, organizational arrangements, knowledge and technology.

Business infrastructure

The business processes of most virtual organizations include a mix of routine development activities, such as planning, product development, sales and marketing, production and delivery. Each will evolve into a set of agreed methods, systems and procedures, which in turn become part of the infrastructure and hence intellectual capital of the interprise.

Knowledge networking is enhanced if key processes are the joint responsibility of more than one member, one acting as a lead partner and others supporting. This forces dialogue and co-operation. Interprise outputs such as the results of market and business research should be widely disseminated. The more knowledge and information collected, shared and discussed, the more the opportunities and risks are clarified. For all activities, each participant should ask themselves: ‘How can I contribute to the success of my fellow partners?’ – that is true collaborative working.

Activity 8.11: Core business processes

Are key processes identified and joint responsibilities allocated? Which are the critical processes on which the joint venture depends? Have these processes sufficient breadth of knowledge and commitment of resources? What processes are predefined, what is determined by joint negotiation? How are new business opportunities allocated?

One of the most difficult challenges in a virtual organization is agreeing how to share costs and benefits. Where a separate joint venture company has been formed, this is taken care of through allocation of share capital and formal accounting, just as in a traditional organization. But when a virtual organization is building, individual members are investing time and money to make it successful. The value of such contributions is difficult to value. Should it be based on normal labour and overhead rates for that organization? Should it be the same for all contributors? Should it be based on the commercial rate for the specific task? Some networks use a notional development rate that is used as network members perform such tasks. These notional credits and debits are put on account and settled when revenue is generated. By balancing development work across the network, settling accounts is less of an issue.

The situation is easier for client projects with definitive revenues. The Phrontis consulting network allocates its revenues broadly as follows:14

• 50 per cent of the overall project value goes directly to those delivering services

• 25 per cent is for marketing and sales: 10 per cent to the lead creator and 15 per cent for closing the sale

• 5 per cent is for quality checking, by a network member not directly involved

• 5 per cent is for administration, order processing, etc.

• 15 per cent is for development activities.

The responsibilities and detailed percentages are agreed up front on a project-by-project basis, as is the ownership of any intellectual property generated.

Organizational infrastructure

An organizational infrastructure is built along similar lines to that of a team as described in Chapter 6. This requires articulation of shared purpose and principles, and a summary of how each partner can enhance the success of each of the others. Developing an ‘offer’-’needs’ matrix for each contributor is a useful tool for identifying gaps and highlighting interdependencies. As with a virtual team the essential ‘glue’ of a virtual organization is regular and extensive communications.

A good basis around which to develop plans and gauge progress is through tracking the performance of the interprise. Define success metrics for the enterprise as a whole as well as for key development projects. Develop a system of information collection and progress monitoring. Use network members not directly involved as reviewers and arbiters.

Virtual organizations vary in their degree of formalism. A small network just starting is likely to develop its operating principles and contractual arrangements as its goes along. Over time these can be formalized in a collaboration agreement (page 229). Most importantly, every interprise must consider how to retain flexibility to change its configuration and membership. This is a healthy process that recognizes that partners’ interests and market conditions change. There are three general situations:

1 Mutual acceptance of the need to change, e.g. one member wants to leave to pursue other ambitions. By updating regularly the list of individual interests, needs and offers, potential changes are anticipated.

2 One member wants to leave, but would leave the interprise with a void. To minimize such occurrences, work out the degree of interdependency at the start and attempt to reduce over-dependency on one member or individual through allocation of tasks.

3 The majority of the network wants to force another member out, perhaps because they are not pulling their weight or failing to meet commitments, or because of other conflicting business relationships. Agreed processes and peer performance review should ease this painful situation.

In all these cases, forward planning helps. Your statement of principles should address changing membership and dispute resolution. Agile Web offers a good example of a virtual organization infrastructure.

Agile Web describes itself as: ‘a new corporate entity that brings together diverse capabilities, complementary skills and entrepreneurial inventiveness from an array of well-established companies to provide a totally integrated capability for fast-response product design and manufacturing’.

Although incorporated as a separate legal entity, the main work is carried out by its twenty-one members, although certain activities are carried out centrally:

• strategic market planning

• the screening and pursuit of specific business opportunities

• the compilation of a core competency data base of its members

• providing a single point of contact for customers

• customizing core competencies to each opportunity (by creating a virtual organization)

• searching for potential members to augment existing competencies.

It has a fourteen-point process for generating opportunities, qualifying customers and building temporary virtual organizations to carry out the tasks required. A neutral team qualifies the opportunity and shares their findings with Agile Web members. For opportunities considered worthy of follow up, members are invited to come together and form a response team. They create a memorandum of agreement with each other as well as with the customer. If the response team makes a recommendation not to proceed, individual members can pursue the opportunity by themselves. For each project revenues are distributed according to the direct (not indirect) costs of every participant, and profits shared according to an agreed formula based on contributions. This methodology, the nuts and bolts of building a successful virtual corporation, is a vital knowledge resource of Agile Web.

The governance of Agile Web is carried out by three committees. The Entity Committee addresses entry and exit policies, limits on competition, dispute resolution and contract liabilities.The Marketing Committee considers product definition, competencies including deficiencies and verification. The Operations Committee develops monitoring procedures and quality control.

The twenty-one participants in Agile Web place trust at a premium - if one member lets down the Web (or Agile Web) the rest suffer. They therefore monitor their own standards and behaviours of each other. Agile Web has therefore developed a set of ethics statements, to which they all subscribe and sign. These include statements about trustworthiness, keeping promises, valuing people and committing to continuous improvement.

Sources: The fourteen-step methodology can be found in Cybercorp by James Martin.15 The full ethics statement can be found at http://www.lehigh.edu/~inbft/ethics.html

Activity 8.12: Develop your intraprise principles

What does the intraprise need to organize to be successful?

• What are basic operating principles for the enterprise?

• Who is responsible for each core development task?

• Prepare an offers/needs chart and agree the process for updating.

Knowledge infrastructure

Knowledge is frequently the interprise’s most important resource and may also be one of its key outputs. Just as within an enterprise, the virtual organization will need to manage its own knowledge - in databases on web pages, holding records of assignments and expertise, working documents and so on.

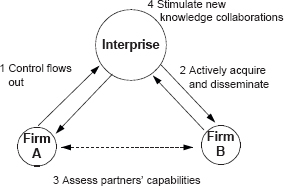

The interprise is also a rich source of knowledge that is often not systematically captured. There are several strategies that a participating enterprise should pursue to maximize the benefits of this collaboratively generated knowledge (Figure 8.7):

1 Control the flow of your proprietary knowledge into the interprise. Determine what knowledge should be made available to the interprise and under what conditions. It could represent a significant commitment, yet be undervalued. Make sure your employees understand which knowledge falls into which category.

2 Extract as much knowledge and experience from collaboration as you can, and disseminate it around your organization. Too often, an interprise has an arm’s length relationship so that the knowledge resides only with those people who have been seconded to it. The Japanese view joint ventures as great sources of learning, something many Western companies have yet to grasp.

3 Continually assess the competency and the capacity of network partners. What knowledge do they have that could be of value to both the interprise and to yourselves?

4 Stimulate new collaborations as ideas emerge. These may be with subgroups within the existing virtual organization or newly constituted intraprises.

Figure 8.7 Strategies for a participating enterprise to exploit interprise knowledge

Therefore, put in place mechanisms to help knowledge flows between the enterprise and interprise. This may be through gatekeepers or regular liaison by participants as a key organizational responsibility.

The technological infrastructure

For many virtual organizations an intranet, or some other form of groupware, provides the basis of the technology infrastructure. Ideally the interprise should have its own intranet which can simply be provided though password protected access to servers in the different enterprises. Depending on what information access has been agreed, different members should be part of their partner’s extranet and vice versa. In other words they can access specified areas of that firm’s own intranet. A typical set up might be:

• Email, using agreed conventions. The interprise may set up its own domain name with alias addresses (such as [email protected], [email protected]) that are routed to specific enterprise addresses according to roles and responsibilities.

• Interprise website, divided into three broad areas: public (Internet accessible); restricted (enterprise members and partners – various grouping) and closed (for interprise workers only). Often individual projects and teams will have their own private areas.

• A conferencing system, such as Lotus Notes or web conferencing. This is useful for the creative development activities of the interprise.

• An agreed set of applications and database formats.

The rules for these follow very much the rules within an enterprise. Difficulties arise because different organizations have different technological architectures and use different software. This means that messaging and document standards must be carefully chosen. Fortunately there is growing interoperability between different email systems and word processors so that messages and documents developed in one system can be read in another. Where this is not true or where specialist applications or databases are involved, the interprise should standardize on one. Do not spend too much time arguing about technology. Use the best that is readily available. After all, it is merely a carrier and interface to the interprise knowledge infrastructure.

Sustaining success

Virtual organizations pose unfamiliar challenges for those used to working in conventional organization settings. The key ingredients for developing a successful virtual corporation are:

1 Each partner must offer some distinctive added value.

2 There should be sufficient members that a viable mix of competencies is provided, but not too many that co-ordination and interfacing becomes difficult.

3 Relationships must be balanced. Dominant partners or high dependency on any one or two makes the virtual organization fragile.

4 Members must develop a high degree of mutual understanding and commitment.

5 Projects and processes should be the focus of co-operation. Usually they will be for clients but some, e.g. marketing product development, can be done by a few members on behalf of the virtual organization as a whole.

6 Key principles or ‘rules of engagement’ need to be defined fairly broadly at the outset, covering areas like responsibilities and reward expectations, sharing of risk and returns. However, momentum is lost if too much is formalized too soon.

7 Members should recognize the need for brokering and co-ordination activities, and either commit time to them or pay for them to be undertaken.

8 A virtual organization needs a clear identity and interface to the outside world. One approach is to complement your individual identity with an addition such as ‘a member of the XYZ federation’. Contracts may either be with one firm acting as prime contractor, or a legally constituted organization ‘the XYZ Federation’.

9 Developing trust is crucial, especially in the early stages of formation, or where there is no shared past, or where virtuality means little face-to-face contact.

10 Plan for reconfiguration or dissolution. Agree how to replace non-performing members with new ones. Continually reaffirm each member’s interests, commitment, competencies and capacity.

The Trust Group is an example of a virtual network whose members are individual contractors, but who gain from being part of a larger skills pool.16 It was formed in 1996 as an evolution of shared interests communicated in a CompuServe forum. It is a voluntary network of IT specialists – programmers, systems analysts and project managers – who make themselves available for short-term contract work. The attraction for individuals is that it helps find them opportunities through shared marketing, while allowing them to remain independent. The Trust Group has developed its business through being able to offer large corporations a highly skilled resource, committed to standards and quality. It may seem like a typical contract agency, but it is run as a club by its members for its members. Its clients do not pay agency fees, and deal direct with individuals after the introductions have been made. A modest subscription covers administration and marketing costs, which include both conventional publicity and a World Wide Web site. Client opportunities are referred to appropriate people with the specialist skills. Teams are assembled for larger projects, by posting requirements on a private Internet newsgroup and website.

Robert Pearson, one of its founders, attributes its success to its members’ level of competence but, more fundamentally, on what its name suggests -trust.

The reality is that many collaborative ventures end in failure. Business networks or electronic communities that start with good intentions fail to move forward. There is nothing as good as a funded project or customer contract to crystallize action, but even then a collaboration champion is needed. Building an interprise is not unlike building a new enterprise from scratch. It therefore needs entrepreneurial zeal and commitment, which may be difficult if individuals already have their time committed to their main employer. Therefore, the more interprising can be made a natural part of the routine work of an enterprise, and a significant time commitment for key employees, the easier it is to develop and sustain. Common reasons why interprises stall, and how the risk can be minimized are:

• Over-optimism – develop a better understanding of partners, especially their competencies, motives and top management commitment.

• No obvious strategic necessity or fit – there is no clear benefit for an individual organization.

• Assigning inappropriate individuals to the interprise - it should have some of your most competent people, not those who just happen to be free.

• Conflicting, neglected or unbalanced interests - motives must be clearly understood; the offers/needs approach helps.

• Cultural or management style incompatibility – early use of a diagnostic tool will help identify potential issues to see if they are insurmountable.

• Changing business context – anticipate the affects of changing regulatory, market conditions and how they affect each enterprise and the interprise as whole.

• Poor marketing both internally and externally – the benefits, core competencies and products need to be sold to attract ongoing revenues and investment.

• Inadequate infrastructure – explicitly address the technical, business, knowledge and organizational infrastructures.

• Unclear or unfair sharing of risks and rewards – develop principles for valuing contributions and sharing of revenues and rewards.

• Festering disputes and unmet commitments - instigate good performance monitoring and methods of dispute resolution.

• Partners abscond or breaks ranks, taking unfair advantage of the others – build in legal safeguards or network surveillance.

Overall, many of these situations can be avoided through constant communications and reinforcing trust, rather than having to resort to legal measures. A little early planning and discussion of key principles can prevent anguish later. Address and resolve small annoyances before they become festering sores.

Summary

This chapter has considered some whys and wherefores of collaborative interprising. Specific attention has been given to creating and sustaining virtual organizations. The diversity of structures and working arrangements is huge, ranging from loosely formed business networks, as in the Danish model, to tightly knit formal virtual organization structures like Agile Web.

Creating a successful interprise extends many of the principles already discussed in earlier chapters in this part of the book, such as the need for an integrated perspective that includes business, organizational, knowledge and technical dimensions. In particular, many of the facets that apply to virtual knowledge teams, discussed in Chapter 6, also apply in the virtual organization. Of these, extensive communications and trust are the core foundations.

Agenda for action

Developing collaboration knowledge

1 Review any existing collaborative arrangements. Draw lessons from their success or failure. Are there organizing principles you can carry over?

2 Identify knowledge and experience of collaborations that exist, either within your organization or in already proven external examples, such as Agile Web.

3 Develop a strategic map, specific for your business, highlighting areas of strategic intent i.e. future strategic moves.

4 Create a potential partners’ database, mapping their key competencies into your strategic map.

5 Review any business networks or virtual organizations that address similar customer needs. Do any of them represent an expanded opportunity for you? Are there practices that can be emulated?

Creating collaboration infrastructures and practices

6 Review your existing technological, business and knowledge infrastructures. How easy is it to modify or extend these to collaborating partners?

7 List your top ten customers. To what extent have you developed deep relationships, knowledge sharing and dialogue for innovation?

8 Review your innovation process. Consider how more external input can be integrated into the process, such as customers, suppliers or external experts.

9 Review your key knowledge databases. Do they include records of collaborative activities? To what extent can they be enriched by direct collaborator involvement?

10 Review various intellectual property contracts you have. Do they inhibit or help future collaboration?

Notes

1 Most interorganizational models are based on exchange theory i.e. each party exchanges some resource or economic ‘good’ for another resource or benefit. Typical of such academic models is that described in Ring, P. S. and Van den Ven, A. H. (1992). Structuring interorganizational relationships. Strategic Management Journal, 13(2), pp. 483–98.

2 Segil, L. (1998). Intelligent Business Alliances. Century Business Books.

3 Amidon, D. M. (1997). Customer innovation: a function of knowledge. Journal of Customer Relationships (5), pp. 28-35.

4 Amidon, D. M. (1997). Customer innovation: a function of knowledge. Journal of Customer Relationships (5), pp. 28–35.

5 Morita, A. (1986). Made in Japan. E. P. Dutton.

6 Angehrn, A. (1997). Designing mature Internet business strategies: the ICDT model. European Management Journal, 15(5), August, pp. 361–369.

7 Angehrn, A. (1998). The strategic implications of the Internet. INSEAD Working Paper at http://www.insead.fr/CALT/Publication/ICDT/strategicImplication.htm.

8 Lorange, P. and Roos, J. (1992). Strategic Alliances: Formation, Implementation and Evolution. Blackwell.

9 EU Innovation Programme ‘Innovation across cultural borders’. The web page http://www.cordis.lu/innovation/src/culture1.htm describes the approach. Associated web pages give six case studies of culture clash and a downloadable software tool based on the diagnostic.

10 Chaston, I. (1995). Danish Technological Institute SME sector network model: implementing broker competencies. Journal of European Industrial Training, 19(1), pp. 10–17.

11 Martinussen, J. and Jantzen, O. (1994). Business networking – a transferable model for a European SME support structure. TII/Focus, August.

12 Krebs, V. (1997). Patterns in the Net. http://www.orgnet.com/netpatterns1.htm

13 The Agility Forum at http://www.agilityforum.org/Ex_proj/MAVE/1.htm.

14 Phrontis Consulting at http://www.phrontis.com

15 Martin, J. (1998). Cybercorp: The New Business Revolution, p. 130, Amacom.

16 The Trust Group at http://www.trustgroup.com.