Chapter 6

The knowledge

team’s toolkit

The fundamental organizational units in the networked knowledge economy are knowledge teams. They are the hubs that gather, develop and apply knowledge to create value. Because of globalization and better communications, an increasing number of teams are virtual teams.

The core of this chapter emanates from a set of principles that were first developed in 1998 when I was part of a self-managed team. They were subsequently adapted for virtual teams1 and have been further refined in this chapter to take account of knowledge. Altogether there are twenty-five core principles. They cover team composition, commitment, processes, technology and knowledge. Before examining the principles, the chapter starts with a review of the thinking behind them: what makes teams successful. To round off the chapter there is practical guidance on the related topic of creating and nurturing knowledge communities.

The activities in this toolkit are designed for the team as a whole, rather than as individual exercises. They are something to do and discuss at team meetings.

Knowledge teams

A group is not a team

Just because people work in the same group does not mean they are a team. Conversely, people from different groups can work together as a team. A team is a cohesive entity whose members share a common purpose and are committed to each other’s success. Katzenbach and Smith, authors of a highly regarded book, succinctly state the case for teams:

Savvy managers have always known that real teams - not just groups of people with a label attached - will invariably outperform the same set of individuals operating in a non-team mode, particularly where multiple skills, experiences and judgements determine performance. Being more flexible than larger organizational groupings, they can be more quickly and effectively assembled, deployed, refocused, disbanded.2

There are many different types of team, including management teams, specialist teams, cross-functional teams and project teams. Some teams, such as an airline crew or a medical team apply and reapply a well-established body of knowledge. Other teams, particularly in development work, are more varied in composition and structure, evolving as their work progresses. Some are permanent. Others are temporary. Some have members who work with each other daily. Others are virtual teams whose members come face to face only occasionally. As organizations become more flexible and work more on a project basis, their teams will work more virtually and change more frequently. Whatever the type of team, there are recurring characteristics in those that perform well.

High-performance teams

Teams that achieve very high levels of performance not only achieve work goals but also team cohesiveness. At the same time every team member is successful at meeting his or her personal goals and ambitions. The visible manifestation of success is an aura of enthusiasm, energy and commitment laced with fun and enjoyment. Such teams:

• are empowered and self-managed

• put teamwork and the team ahead of individual stardom

• assume collective responsibility – members represent the team as a whole

• have members who are committed to each other – they share knowledge, support and coach each other, exhibit trust, discretion and responsibility

• dynamically change roles and tasks to achieve desired results

• value diversity; ideas are challenged; debate is intense

• continually test the boundaries of freedom

• are never satisfied with the status quo; they seek innovation, continuous learning and improvement

• receive support and encouragement from management.3

Table 6.1 Characteristics distinguishing high performance from other effective teams

| Reactive | Proactive | High performing | |

| Perspectives | |||

| Time horizons | Past and present | Present and future | Timelines and trajectories |

| Focus Motivation Knowledge |

Action Reward Given, unchallenged |

Anticipation Achievement Sought, experienced |

Innovation Excellence Created, challenged |

| Strategy | Predefined Operational | Evolving Customer oriented | Emergent Value focused |

| Organization and processes | |||

| Structure Roles Relationships Communications |

Hierarchy Defined/stable Competitive Inward and vertical |

Heterarchy Assumed Collaborative Outward and lateral | Network Negotiated/dynamic Mutual commitments Open and extensive |

| Development | Targeted improvements | Systematic continuous learning | Team challenge |

| Task focus | Process focus | Innovation focus | |

| Work management | Command and control | Workflow and co-ordination | Pattern filling |

| Leadership style | Directive | Coaching, facilitation | Self-managed |

| Use of technology | Procedural As needed | Informational Regular sensing | Team knowledge Exploratory |

Table 6.1 contrasts some of the factors found in high-performing innovative teams with those who are otherwise effective, but merely reactive or proactive.

Activity 6.1: What sort of team are you?

Review Table 6.1. Each individual should independently plot where they think the team is against each characteristic (row by row). Then come together and discuss differences. For each characteristic you deem important, and where you are only reactive or proactive, discuss what is stopping you becoming a high-performing team. Is it something within or beyond the team’s control?

High-performing teams focus as much on people and processes as they do on tasks. This is a particular challenge for those working in many innovative environments, such as research or engineering, which are frequently too task focused. By ignoring the social context, team dynamics and processes, many teams fail to achieve their full potential, while their members suffer stress and burnout.

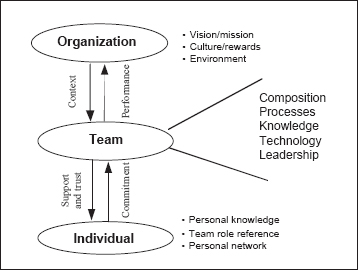

Creating the context

Team performance is heavily influenced by the individuals within them and the organizational context within which they operate (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Key elements that determine team performance

The organizational context is covered in the next chapter. Regarding individuals, a good team player is one who:

• contributes knowledge and is effective, along the lines described in Chapter 5

• has team roles that match their expertise and personal preferences

• values every other team member for their contribution and has positive expectations

• learns from other team members, from the results of their own actions, and from collective experience

• demonstrates a high level of trust

• builds mutually supportive relationships, with a corresponding degree of give and take

• keeps commitments they have made; where circumstances prevent this, other team members must be informed as soon as possible

• represents the whole team and does not criticize colleagues in public

• expresses their feelings and recognizes the feelings of their team colleagues.

Activity 6.2: The team context

At one of your team meetings, consider how well the organizational environment supports your team goals and needs. Discuss what makes an ideal team member. Contrast your list with that above.

Teams are nodes in knowledge networks

A knowledge team is as a node in a knowledge network (Figure 6.2). The node is the focus of a knowledge intensive task or group of tasks. It is where knowledge is gathered, developed and converted into useful outputs. In a virtual team, the node is not in any single physical location but is dispersed. The links between teams can be formal work processes, overlapping responsibilities and activities, or personal connections, both formal and informal, such as in a community of practice. The strength and breadth of these links determines the capacity to share and develop knowledge through the network. Our principles are therefore designed to create effective knowledge processing nodes that tap into the flows in the knowledge network.

Figure 6.2 Teams as nodes in networks with multiple linkages

Twenty-five principles for effective teams

The team toolkit is based around twenty-five key principles, divided into five groups:

1 Teams and teaming – creating the composition and structure of a team.

2 Team commitment – vision, mission and other factors that build team commitment.

3 Team processes – especially communications and building trust.

4 Team technology – that bolsters communications and knowledge processes.

5 Team knowledge – the vital resource and output of a knowledge team.

Each group of the toolkit is now considered, with the key principles first, followed by discussion and further guidelines.

Teams and teaming

1 Teams are the organizational units that create focus and harness individual talents. Create a network of knowledge teams to develop your organizational knowledge and achieve success.

2 The most productive knowledge teams are small multidisciplinary teams of five to seven people with a variety of backgrounds and personality traits.

3 Larger teams are usually loosely federated groups or committees which may be used to pass information (often ineffectively), motivate, or provide a sense of identity. They are rarely effective work teams. Use larger groupings to create cohesion, reinforce values and to provide networking and knowledge sharing opportunities, but not as the primary unit for organizing work.

4 Every knowledge worker should belong to at least two separate teams. This helps the organization achieve cross-functional cooperation; it provides knowledge-sharing links between different teams and it helps the individuals gain a broader perspective.

5 An individual can have one or several roles in the team. These roles can change and be exchanged (for example during holiday periods, to balance workloads, or to broaden individual experience). Distinguish the role from the person.

Teams are organized around a set of tasks. Ideally a team is chosen according to the mix of talent needed to perform these tasks. Diversity in perspectives, culture, age and gender also helps in tackling challenging assignments and making innovative breakthroughs. In the networked organization, many teams will be self-forming, by attracting people with the right motivation and expertise. It also helps if several members of a new team have previously worked together.

Teams are dynamic. As new needs emerge, workload grows or tasks change, team composition must adjust accordingly. If a team gets too large split it into two comparable or complementary teams. Regularly review the team’s network connections. If communication patterns are denser between teams than within a team, consider redrawing boundaries. Regular restructuring will also help the diffusion of knowledge around an organization as individuals move between teams. This dynamic, though, has to be balanced against the time taken to build team commitment. Some ‘slack’ should be built into the network. A certain amount of duplication or overlap should not be viewed as bad. This slackness permits a higher quality of output, plus a resilience to cope with the unexpected.

Roles and relationships

As well as specific task roles, there are a number of team roles that need filling. These roles include co-ordinating work, scheduling, liaising, planning, budgeting, etc. In particular there are knowledge roles to fill, such as the knowledge gatherer who scouts for external knowledge, the knowledge analyst who interprets client needs and the knowledge manager who organizes the team’s knowledge resources. Some of these roles can be shared responsibilities, while others are performed by one person. Teams run into problems when these roles are not initially assigned or where there is role ambiguity. On the other hand, some overlap in roles is useful, so that people can learn from each other and provide cover during a colleague’s absence.

Meredith Belbin’s research into teams identified eight roles other than specialist:4

1 Plant – who stimulates the team with new ideas, often unorthodox views on solving problems.

2 Resource investigator – who networks and brings external information into the team.

3 Monitor-evaluator – the analyst who logically evaluates situations.

4 Team worker – people oriented, who supports other members and helps foster team spirit.

5 Completer-finisher – painstaking, attention to detail and seeks closure on loose ends.

6 Implementor – organizing ability, turns plans into practical procedures.

7 Chairperson – helps the team move forward by drawing on the strengths of each individual.

8 Shaper – a dynamic person who prioritizes and shapes direction of team effort.

There are obvious similarities with individual personality and thinking styles. Thus the red thinker (the logical person) is more likely be a monitor-evaluator or completer-finisher. Belbin’s formula for a successful team is a good chairman, one strong plant, and a general spread in both team roles and mental attributes. He also found that the cleverest teams (with many plants) were often the least successful. They vie with each other intellectually, but fail to address crucial team processes and communications, both internally and with their clients. Add a team leader and team effectiveness considerably increases. If your team is not performing well, check if it has just resource investigators and plants, leading to a talking shop, or just team workers and implementors who plod on in an orderly way but fail to grasp new ideas.

Activity 6.3: Your team characteristics

Review the principles and the set of roles. How closely does your team follow them? How many other teams does your team actively link to through personal membership? What are the interdependencies? Do you need skills or role behaviours (Belbin) in your team that are absent? How can you change your team and its composition to fill these gaps?

Team commitment

6 Every team must have a defining purpose if it is to act as a team and not as a group. It must have its own vision, mission and goals which reinforce those of the organization.

7 Every team should develop a strong set of cultural norms and values. Hence regular team meetings should take place. A set of working principles should be developed (print them on a laminated card).

8 Each team should identify other teams carrying out related or dependent activities. It should draw a network diagram with:

(a) itself (and its mission) at the centre

(b) an inner ring of teams (nodes) where interdependencies are high (formal relationships)

(c) an outer ring of collaborative teams (mostly information sharing).

9 Each team should make its core processes explicit. Identify the sequencing of main activities and their interdependencies (who provides what to whom)

10 Individual members of teams should maintain their personal and professional networks, even beyond the immediate requirements of current activities.

Achieving team commitment is the most challenging, yet the most rewarding, of team-building activities. Teams that have high commitment have in place a keystone of high performance. They have a compelling vision, a distinctive mission, clear goals and a realistic plan of action, all set within the context of the organization’s mission and strategy.

From vision to reality

In developing commitment, work from the abstract to the specific, along the following lines:

• Team vision. This should be inspirational, and a pointer to the future. Capture the essence in a memorable phrase, such as ‘knowledge in motion’ (for a logistics team).

• Mission. Avoid commonly found bland statements such as ‘best in customer service’. A good mission statement reflects the team’s raison d’etre and ethos. Thus, it might describe your core competencies and activities, the customers you serve and what benefits you deliver to them.

• Norms and values. Describe the ethics and standards of behaviour that can be expected from the team and from each other, e.g. respect for the individual, honesty, valuing diversity, a commitment to quality, etc. Express them in the form ‘Our (or my) commitment to you is … ‘. Many will follow directly from reaffirming some key principles from this chapter.

• Goals. These are tangible measurable objectives, both short and long term, for each project or area of responsibility. Good goals are stretching. They are not merely extrapolations of the present. Make sure you have goals for developing and exploiting the team’s knowledge assets.

• Tasks. Allocate and sequence tasks to achieve team goals. Remember to allocate roles for team support tasks and for virtual teams, take account of which locations are best suited to what types of task.

• Decision-making. Agree what decisions need team consensus and what is delegated to individuals.

• Identity. This is how a team portrays itself, internally and externally. Identity manifests itself in slogans, logos, communications, job and role titles and generally how the team describes itself.

These aspects of team organization should be developed by the team as a team. Visions and missions are not dictated. They should evolve from within the heart of the team.

Team-building – where face to face matters

Teams commonly go through a sequence of development steps before they become fully effective. One model that provides a useful framework for team development that is consistent with the twenty-five principles is the Drexler/Sibbet Team Performance Model. It blends both the social and task requirements of team-building through seven stages:5

1 Orientation – why are we here?

2 Trust-building – who are you?

3 Goal/role clarification – what are we doing?

4 Commitment – how will we do it?

5 Implementation – who does what when where?

6 High performance – what are we capable of achieving?

7 Renewal – why continue?

It is important to iterate between each stage. In the early stages build relationships and get to know each other’s strengths. In global teams, explore your cultural differences. Hold meetings at different locations around the world, and not just at corporate headquarters.

Commitment grows through high levels of communication and interchange of ideas. Even in those organizations where computer communications is the norm, it is found that teams which come together regularly in person typically outperform those who don’t. Face-to-face meetings provide an effective way of deepening relationships.

Team development takes time. Do not assume it will occur naturally. Schedule time for ‘away days’ and allocate time for team development at every team meeting. Using skilled independent facilitators also helps considerably. Make your meetings invigorating and motivating:

• Celebrate team and individual successes.

• Continually re-examine team processes – review their effectiveness and scope for improvement.

• Reflect and review – at the end of each agenda item, allow time for each team member to offer some words of reflection on what they have learnt.

• Explore differences of opinion. Delve beneath the surface, explore assumptions, and validate that commitments are realistic by analysing progress and task dependencies.

Through such team-building processes, a common language develops, helping to create team identity and shared understanding.

Team processes

11 Communicate, communicate, communicate – frequently, both within the team and to your wider network. Think about the best media for each type of communications and apply the techniques of effective communications (Chapter 5). If you are in a virtual team, make sure you also communicate socially in between face-to-face meetings.

12 Develop clear mutual understanding through active listening and ‘playing back’. Monitor feedback and be sensitive to lack of response. After face-to-face meetings reaffirm decisions or understandings in a follow up email.

13 Recognize the unpredictability and fuzziness of decision-making processes. An action taken might imply a decision taken. Be guided by your mission, values and principles. Understand which types of decision are fundamental and should be agreed up front, and develop simple formal processes for these. Otherwise keep formality to a minimum.

14 Learn together – all the time. Coach each other. Critique each other’s actions and output. Share your respective knowledge and skills. Reflect and learn from your successes and failures.

15 Build trust in depth. Although formal relationships within and between teams are best cemented by having agreed written processes (‘rules of engagement’) on key interdependencies, aim for higher trust and openness rather than higher formality. Adjust your frequency of communications according to criticality of the linkages.

Communications is the most fundamental team process. It underpins all the others. Whole team communications builds on those for individuals described in Chapter 5. Each team should develop its own set of communications principles taking into consideration:

• Accessibility – who can be contacted when and where, taking account of different time zones and individual movements.

• Preferred media – for routine, confidential and urgent messages. Many teams find email or groupware the most convenient medium for most communications since it is any time, any place.

• Regular communications – such as diaries, project and activity reporting. Use a standard structure and format to make it easier for users to find what they want.

• Team storage – where to find current team documents, e.g. processes, contacts, schedule, assignments, outstanding items – so that the latest team knowledge is readily accessible.

• Patterns and styles – deciding what types of communication are private, what is for the team, what’s public?

• Role of meetings, especially whole team meetings – many virtual teams have regular (say weekly or biweekly) whole team meetings using audioconferencing or videoconferencing.

Communications in Ford’s virtual teams

Ford has many designers in virtual teams. Richard Riff manages one programme that has five project managers and twenty other people who report directly to him. They are located in Europe, South Africa, South America, Japan, Australia and China. He holds weekly videoconferencing and one-to-one telephone conversations with each of his staff. There is also a quarterly virtual team meeting. He also visits each of the teams at least once a year:’ Technology can’t replace the chemistry of personal contact and coaching. It’s the personal touch of seeing me once or twice a year.’6 Communicating a good flow of information is, he says, the most critical success factor.

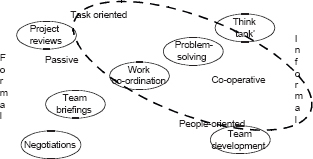

Constructive conversations through structured dialogue

Communications vary widely in their degree of structure and codification (Figure 6.3). Whereas formal written communication may be highly structured, informal conversations may appear very unstructured wandering from topic to topic in an apparently haphazard way as the discourse unfolds. A useful discipline is that of structured dialogue, a halfway house between the two extremes. This puts purposeful conversations into a framework that helps knowledge exchange and codification.

Figure 6.3 The communications spectrum according to knowledge

One model that adds a degree of structure to dialogue is the IBIS (Issues-Based Information System7) conversation model which is based around four primary conversational elements - questions, ideas, pros and cons. Jeff Conklin describes how a five-person software team used IBIS as the structure of their design meeting minutes. As a result they identified errors in the software specification at a much earlier stage than would otherwise have occurred, with an estimated savings of three to six times their investment in the lengthier dialogue.7

A more sophisticated method is that of Team Syntegrity, based on the cybernetics principles of Stafford Beer. It follows a precise structure and timetable over a three to five day period based around the geometry of a polyhedron. The thirty edges of the polyhedron represent individual stakeholders, the apexes represent topics for discussion, and the twelve surfaces represent dialogue teams. Following the geometry each individual is a participant in two dialogues, but they also act as critics on two others. Those who have participated in Team Syntegrity sessions attest to its effectiveness. According to Allenna Leonard, it results in: ‘a high degree of emotional connection as well as shared information. The process is powerful; the topics chosen are close to the heart and the discussion is intense’.9

You don’t need to go as far as this for more straightforward decision-making or problem-solving. An effective technique useful in almost any meeting is that of wall charting. A question is posed, individuals generate single phrase answers on cards or adhesive notes, which are then grouped onto a whiteboard for further exploration and discussion.

Trust – the linchpin

A team with trust is one that gives its members a high degree of autonomy to act on behalf of the team. In most team situations, and especially in virtual teams, trust builds up over time. However, there are many situations where trust needs to be more immediate. For example, you trust somebody who is a complete stranger, such as the pilot of your airline flight. Such ‘swift’ trust depends on context and on the reputation of the organization and the person. We tend to trust people as long as they fulfil our expectations. When they do not, trust can evaporate quickly and take much longer to rebuild.

Sirkka Jarvenpaa and Thomas Shaw, researchers of virtual teams, write on trust: ‘In a virtual organization, trust is the heartbeat. Only trust can prevent geographical and organizational distances of team members from turning to unmanageable psychological distances. Only through trust can members be assured of others’ willingness and ability to deliver on their obligations.’10 Their research indicates that trust is initially built on personal referral or early disclosure of aspirations, but that it strengthens over time through communications and interaction, predictability and demonstrable capability. A key conclusion of her research with Dorothy Leidner was that high trust can be created in totally virtual teams even where people have no common past, as long as there is a focus on tasks, extensive and balanced communication and the ability to take initiative, manage uncertainty and expectations. Also, first impressions count: ‘Trust might be imputed, but is more likely created via a communications behaviour established in the first few keystrokes’.11

Here are seven practical ways to hasten development of trust:

1 Clarify expectations. Be as explicit as you can.

2 When making important commitments, use face-to-face communications or videoconferencing to agree the commitment backed up by a hard record, e.g. on email.

3 Don’t over commit. Make small commitments and meet them.

4 Communicate frequently and clearly. Remain alert for any possible misunderstandings.

5 Demonstrate interest and commitment to your team colleagues. Do things for them that will help them succeed. Address any negative emotions quickly.

6 Remind colleagues gently if they have not met their obligations or your trust, but do not make a big deal out of it.

7 Socialize – through informal emails if you can’t meet face to face. Have conversations (via email if necessary) about shared interests beyond the immediate business tasks. This helps build closer personal bonds.

Activity 6.4: How good are your team processes?

List your processes in three groups – communications, core work processes, support processes. Make sure that there are clear linkages to the team roles you identified in Activity 6.3. Now go through each in turn, assigning a priority, saying what is good about each one, and what needs improving. Having gone through the list, pick out five process areas for improvement. Are there some common elements that suggest a new team development activity? Unless you already have a working list of core processes, this is likely to be a two to three hour team exercise. But the time spent will be rewarded many fold through increased performance.

Team technologies

16 Consider how various technologies could enhance team communications, work processes, meetings or team knowledge. Consider a wide range, from voice communications to groupware.

17 Agree on standards. Select a common core set of products and services – word processing, email, groupware, etc.

18 Go web-centric for important team documents. Create a team knowledge repository (on your intranet). Your documents can later be published for a wider internal or external audience.

19 Agree on content and usage standards when using the technologies, e.g. headings for emails, information structure in groupware databases, forwarding of messages.

20 Do not use technology just for the sake of it. Err on the side of proven rather than experimental technologies, but keep an open eye for opportunities to pilot technologies that could be beneficial.

As discussed in Chapter 3, there is a wide range of technologies that can enhance knowledge activities. From the team perspective, the important ones are those that help people communicate and collaborate. Table 6.2 shows a functional hierarchy of some of the commonly used technologies.

Every team should have access to a range of these, so that the functional spectrum is covered. More important than the choice of any specific technology, though, is how effectively they are used. The effective use of email was covered in Chapter 5. Below, guidance is given on the effective use of two other contrasting technologies from Table 6.2 - computer conferencing and videoconferencing.

Table 6.2 Functional hierarchy of team technologies

| Function | Synchronous | Asynchronous | Comments |

| Collaboration | Electronic whiteboard | Document management Web pages | Shared knowledge sources |

| Conversation (structured) | Meeting support (GDSS) | Computer conferencing | More structured and explicit |

| Communication (basic) | Videoconferencing Telephone | Email Voicemail | Asynchronous communications can be retained as part of organizational memory |

Figure 6.4 Types of meeting most appropriate for conferencing

Computer conferencing – developing knowledge

As described in Chapter 3, computer conferencing performs several roles – facilitating communications, providing access to information and acting as a meeting substitute. The types of meeting where substitution by conferencing makes the most sense are shown within the dashed area of Figure 6.4.

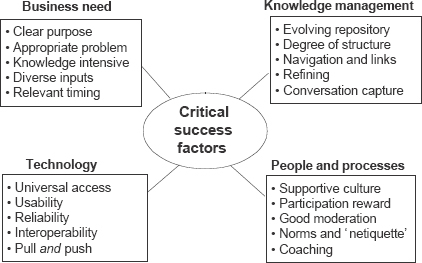

Conferencing also helps teams interact better with their wider network, by testing new product ideas, posting solutions to customer problems and responding to suggestions. Many team conferences are restricted in membership so that confidential matters can be discussed. A problem in many organizations is that conferences languish after an initial flush of enthusiasm. There are several reasons for this, not least of which is that the conference is not achieving anything more than what could be easily handled by other means such as email. Figure 6.5 shows factors that underpin a successful conference:

Figure 6.5 Critical success factors for a computer conference

• A clear business need and an appropriate task that evolves over time and needs multiple inputs. Conferencing is not appropriate for urgent, single person tasks.

• The technology must be easy to access and use. Poor network access and reliability will discourage its use.

• Good information and knowledge management. The conference must be well structured so users can quickly find relevant information and contribute.

• The conference must take account of personal behaviour. If there are too many irrelevant contributions or people have to hunt for things that affect them, it will be discredited.

Ways to develop effective team conferences are:

• Actively solicit feedback – in a team you should be able to get frank feedback. A conference allows feedback to be structured according to specific topics.

• Recognize positive contributions – openly express appreciation.

• Be responsive – try and respond to most postings within a day. If you need time for a more informed comment, acknowledge receipt and say when you will respond more fully.

• Be more open about expressing concerns, although when criticizing always start positively with what you do like.

• In documents or reference information clearly identify the author, date, version and status.

• Regularly summarize conference conversations, so that you build up a valuable resource library, including such items as rationale for decisions, project histories, best practices, useful contacts, etc.

Conferences should have both private and public virtual workspaces. With appropriate facilities they can become the hub of a team’s knowledge exchange, particularly for virtual teams. Lotus TeamRoom shows what is possible, and how good conferencing can fundamentally change the way that teams collaborate.

One of the most crucial factors behind most worthwhile conferences is a good moderator, who ensures a relevant flow of contributions and encourages active participation by all the team.

The role of moderator is discussed later in this chapter.

Lotus TeamRoom was developed at the Lotus Institute, following research and experimentation with collaborative team technologies. It originated in a project to improve the performance and quality of work life at Lotus. Meetings were the primary means of group collaboration but proved difficult to organize because of people’s locations and schedules.Therefore email was widely used for co-ordination and sharing information, the phone for one-to-one discussions and clarification of email messages, and Lotus Notes’ discussion databases (conferences) and document libraries for communicating beyond the team. However, Lotus Notes was little used within the project team. TeamRoom added facilities that made this more practical:

• Users can modify the environment to suit their own preferences. Documents can be private or shared.

• There are team areas and personal workspace, which users can organize to suit their own preferences.

• There are links between discussion databases and email. Users can choose whether information is accessed by email or TeamRoom. They can be alerted by email if new information comes into specified areas of TeamRoom.

• TeamRoom allows them to assign categories to messages such as for discussion, action request, reference, meeting announcements.

• A structure for team co-ordination is provided through a mission page and linked user applications.

In common with many other groupware situations, the technology was merely an enabler, but not the driver of change. It was the encouragement and active coaching of users that changed the way the team worked. By changing their focus from email to the TeamRoom areas, they could see communications and information within its wider team structure.

Videoconferencing – enriching remote conversations

Videoconferencing is becoming as essential tool for many knowledge teams. While its use is not yet as natural as picking up the telephone, it is a commonly used tool in many organizations. As well as using it for scheduled meetings many knowledge teams use videoconferencing for ad hoc discussions when visual contact is helpful. A particularly useful feature is the ‘joint viewing’ of documents. Participants share a common view of a document on the screen, while discussing and amending it.

Using videoconferencing is quite straightforward, but there are a number of practical guidelines that catch out beginners, and will also help those familiar make better use of it:

• For multisite conferences, plan ahead - check availability and time restrictions; set an outline agenda.

• In a room setting, make sure one person is familiar with the camera operation and can zoom in on relevant people or objects; use camera presets to change the view and add interest.

• Be aware of technological limitations: use the ‘mute’ button to cut out background noise while others are speaking.

• Make yourself video friendly – wear pastel coloured clothes – avoid strong patterns, stripes and red. Look at the camera while speaking, avoid rapid movement. Pause frequently. Be natural.

Activity 6.5: Review your team technologies

List your team core processes and knowledge development activities. For each, consider what technologies could enhance them and how they might be introduced. For technologies you currently use, consider how they help or hinder key processes and knowledge development activities. Develop a plan that prioritizes technology improvements and how to learn to use them more effectively in team settings.

Managing team knowledge

21 Knowledge is an important team asset. Every team member should have some responsibility in their area of expertise for collating and distributing team knowledge. However, other knowledge roles, such as librarian, knowledge editor, gatekeeper and brokers should be specifically recognized and assigned.

22 Create a team knowledge repository organized according to one or more well understood structures. Business processes, domains of knowledge and categories of stakeholder are suitable categories.

23 Regard email exchanges and conference discussions as embryonic knowledge. In developing discussions, build on knowledge that exists or has been expressed. Archive them for future retrieval and knowledge ‘refining’.

24 For each main task area or domain of expertise, appoint a knowledge editor. Their role is to take the best from this transitory information and compile it into a more structured document or web page for ongoing reference.

25 Be sure to capture lessons from team processes and projects. Over time this becomes team memory and a vital resource for future occasions and other part of the organization.

Teams generate so much informal knowledge in day-to-day work that they overlook the necessity to capture and store some of it in a more permanent knowledge repository. This is especially necessary as teams evolve and change. For example, continuity in a long project is helped when assumptions and rationale for decisions are recorded.

At first, some of the aspects of managing team knowledge may seem onerous. But the savings in time by having a well-organized team knowledge repository amply repay the initial investment. Many organizations will have knowledge centres to take care of these activities on an organization-wide basis. However, they rely on a good flow of knowledge to and from various teams. Therefore, teams need to be clear about what knowledge it wants to manage more effectively. This will be a mix of tacit and explicit, of formal and informal, and will almost certainly comprise key documents, selected emails and web pages intended for those outside the team.

Team knowledge development and innovation

High-performing teams usually exhibit higher than average creativity. Chapter 5 gave some pointers as to some of the many techniques used to enhance creativity. In a team setting ways to enhance creativity and develop team knowledge include:

• having a stimulating and distraction free environment – often this means working in a location away from the main office

• brainstorming – team members should suspend judgement however crazy an idea may seem

• learning from recent past – asking a lot of ‘what if’ questions

• repeated experimentation – learn by doing and take risks. Adopt an idea and move it forward. 3M did not get where they are by playing safe

• making the team workplace conducive to thinking and stimulating discussion. Introduce soft furnishings, put up wall murals, have funny gadgets and sculptures – anything to create a talking point.

Virtual teams can introduce analogous practices, such as devoting a team discussion document to novel ideas, adding a ‘thought for the day’ on your email signature. Why not have the ‘crazy but it might work idea of the month’ award at team meetings?

Team memory

Team memory evolves from deliberations, decisions and actions. The knowledge generated needs capturing and managing. Computerized decision support systems that capture conversations can create useful both short- and long-term memory. Jeff Conklin cites an example of the use of QuestMap to capture key points in planning meetings for a utility company.12 Three months after discussing pricing criteria, the group started to discuss this topic again. However, within a few seconds the facilitator had brought up the results of their previous deliberations, allowing the team to carry on from where they had previously left off. Rapid memory recall was also useful for an environmental scheme that had been discussed in detail but then shelved.

Teams should therefore give attention to the processes that develop team memory. They should regularly review and refine team knowledge bases, and convert their tacit knowledge into more explicit knowledge and map its flows to and from the team as part of their organization’s wider knowledge network.

Activity 6.6: Enhance your team knowledge

What is your team’s core knowledge? Where is it held? How could it be better packaged and made more readily available to other nodes in your team’s knowledge network? What are the most important knowledge flows into and out of the team? How could they be better managed? Develop a plan and assign responsibilities for knowledge development roles.

Sustaining high performance

Teams face many challenges in creating and sustaining high performance. Frequently, members move and the demands placed on them change. Therefore, flexibility is paramount. Shared statements of principle are much better than detailed manuals of team processes. Teams must also work hard to maintain cohesion and avoid divisions. Members can help each other by being open on how they see each other’s styles and behaviour, and expressing feelings more openly.

Global teams also face challenges of cultural differences. Although online culture tends to mask the differences, some nationalities rely much more on socialization and tacit knowledge rather than the written word. In his classic work on national differences Hofstede mapped national culture along four dimensions.13 One dimension is individualism vs collectivism, which shows the USA having by far and being the highest individualist, followed by Australia, UK and Canada. In contrast, societies that work more cohesively include Latin America and some Far Eastern countries (though not Japan). On a competitive vs collaborative dimension, Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands are high in collaboration. Thus people from certain nationalities may gel more quickly into collaborative teams than others. In practice, corporate cultures and individual traits often matter more. Sensitivity to different national cultures is just another aspect of valuing diversity.

To keep achieving, teams must regularly celebrate success, and revisit their vision to keep it inspiring. To maintain enthusiasm, it must experiment, try out different formats for meetings and organize social events. In my experience the biggest causes of failures in teams are:

• not having a compelling shared vision

• not clearly identifying team roles

• having team missions and goals incompatible with individuals’ aspirations

• having dominant personalities

• not communicating sufficiently and clearly enough

• devoting insufficient time and attention to team processes

• getting complacent.

Virtual teams face the additional challenge of separation. However, there is little evidence that a geographically dispersed team is any less effective than one based at a single location. On the contrary, there is some evidence that people put more effort into making remote linkages and communication work because there is less opportunity to meet face-to-face. One such team that puts several of the principles described in this chapter into practice is that of European Telework Development (ETD).

Virtual global collaboration: the ETD experience

European Telework Development (see page 111) is a project that consists of more than thirty organizations and individuals working in various virtual arrangements. Among its many teams are a management team, two teams of national co-ordinators and a media team. Most of its participants were already experienced teleworkers and extensive users of email before joining ETD. In reflecting on what makes these virtual teams effective, the team leaders drew the following lessons from their experience:

• Subdivide into smaller task teams for emergent tasks that are not obviously the remit of one team and are not high enough on their priority list.

• Allow time for relationships to develop and teams to gel; the occasional face-to-face meeting is an advantage, but with the right skill at electronic communications, is not essential for many tasks.

• Develop technical support mechanisms to help people with their technical problems; the state of the Internet, service provision and quality of software is very variable across Europe (and the world).

• Develop ‘standards’ for communication; these include technical standards e.g. using MIME for email attachments, content standards, e.g. predefined templates for different document types, and procedures, e.g. not automatically copying every recipient when replying to an email.

• Structure information and messages well, using clear titles, identifying information type or status (e.g. draft, request for action etc.).

• Keep filing away those email contacts of people who conduct themselves well over networks; it’s an essential skill for virtual knowledge transfer and such people are an extended team resource – they might even become a team member in future!

Knowledge communities

Teams interact with wider knowledge networks. Their members will frequently be members of communities of practice that span the organization. George Pór describes communities as ‘connecting islands of knowledge into self-organizing, knowledge sharing networks’. While some communities focus on a particular profession or discipline, the most powerful communities are customer or problem focused. They transcend disciplines and bring in different perspectives. They exchange, develop and apply knowledge. Just as a knowledge team is more cohesive than a work group, a knowledge community is a more cohesive cluster within a diffuse knowledge network. Table 6.3 highlights the essential differences between groups, teams, networks and communities.

Table 6.3 Knowledge communities contrasted with other groups

| Work group | Team | Knowledge network (CoI) | Knowledge community (CoP) | |

| Typical size | 3-30 | 5-8 | 30-300 | 15-150 |

| Membership | Recruited for job | Recruited for team fit | Self-selecting | Self-selecting |

| Focus | Tasks | Output | Knowledge exchange | Applied knowledge |

| Goals | Explicit, given | Mutually agreed | Imprecise or implicit | Evolving and purposeful |

| Boundaries | Precise | Permeable | Fluid | Mutually adjusting |

Note: CoI = community of interest; CoP = community of practice

The main difference compared to a team in that the membership is self-selecting. Like a self-managed team they cannot be strongly directed or over directed. In fact the best management style for an in-house knowledge community is hands-off, but providing a climate in which they thrive. Communities are more social than structural. Etienne Wenger (an originator of communities of practice), and Bill Snyder list the following stages of community development:14

1 Latent: there is potential for such a community within the organization.

2 Coalescent: members come together and recognize their collective potential.

3 Active: engaged in developing a practice.

4 Legitimized: recognized as a valuable entity.

5 Strategic: central to the success of an organization.

6 Transformational: capable of redefining its environment.

7 In Diaspora: dispersed but still alive as a force.

8 Memorable: no longer very relevant, but still remembered as part of member’s identities.

Compared to a knowledge team, the size of a community means that it loses some of the cohesiveness and commitment. However, good communities retain as many characteristics of effective knowledge teams as possible, including a shared sense of purpose, intensive external networking, effective knowledge management and trust. Many communities embody such considerations into their guiding principles.15 The two most important parameters are a high flow of communications and passionate community leaders. In the virtual environment this role is performed by a person known as the conference host or moderator.

Virtual moderation for knowledge development

The role of a conference moderator is to stimulate virtual discussion and to guide the community forwards in its thinking and knowledge development. A good moderator has enthusiasm for their subject and likes networking. For most, moderating is not their primary job, but an important added daily activity. They activate knowledge development by:

• Setting up conferences – admitting members, assigning privileges etc.

• Defining the scope and agenda for discussion – posing key questions.

• Defining the ground rules, e.g. no personal insults, no advertising.

• Keeping conversations developing – stimulating discussion, revisiting earlier topics.

• Summarizing – periodically reviewing progress and key contributions and maintaining a coherent structure.

• Cross-linking – connecting different conversational threads; this cross-fertilization often sparks new ideas and momentum.

• Managing inappropriate contributions or behaviour – defusing arguments (more of this is done behind the scenes with private emails or telephone conversations).

• Engaging people in conversation – actively seeking contributions from those they know have something worthwhile to contribute; visibly acknowledging good contributions.

Significant effort is needed in the early stages to gather momentum. Initially, it is usually better to organize conferences by broad topic areas, to get a critical mass for meaningful discussion. One can always subdivide later into more specific topics. Once up and running, Lisa Kimball suggests asking three simple questions to verify that a conference is progressing well:

1 Is the discussion moving forward?

2 Is it interesting?

3 Can new people find their way?16

Good conference leaders will identify important and challenging tasks that will benefit the whole community and keep the knowledge flowing, e.g. preparation of a best practice guidebook, a resources database, etc.

Sustaining communities

Those organizations that encourage communities as an integral part of corporate knowledge programmes will gain significant benefits. Good knowledge communities will be thought leaders, generating new product ideas and aggregating the collective thinking of a talented group of individuals to tackle difficult problems. They will significantly increase an organization’s knowledge capital.

A potential threat to communities is that the very focus on knowledge management introduces a degree of formalization that could, if not dealt with sensitively, stifle them. How can organizations minimize this risk?

• Provide facilities that make it easy for these communities to meet and exchange: web space, internal newsgroups, mail lists; as well as physical meeting places where tacit knowledge conversion can take place.

• Offer facilitation to help them improve current processes - too often communities get bogged down in the content, not stepping back and seeing the effectiveness of their ongoing processes, e.g. when enrolling new members.

• Provide connection information – help others who share their interests apply to join, help them publicize their existence to the outside world, e.g. via community directories.

• Encourage note taking methods for meetings - have community members synthesize ‘knowledge nuggets’, that can be recalled and shared with those not at the meeting.

• Synthesize and edit email discussions – create ‘knowledge editor’ roles, people who respect their norms and values – some communities may want to remain small and intimate, and restrict membership.

Communities need a supportive organizational environment. An easy way to kill a community is to discourage people from spending time at it, or even, as some managers have tried, to suppress this ‘non-essential work’. Reward systems and culture must support community participation. Endorsement, not enforcement, is the watchword. The whole ethos of a successful community is based much more on a knowledge ecology rather than a knowledge management emphasis (see Table 2.1). A good example of knowledge ecology in action is that of the Knowledge Ecology Fair.

The Knowledge Ecology Fair

Knowledge Ecology Fair 1998 was an on-line event that attracted over 300 virtual attendees and ran for three weeks.17 The World Wide Web provided an entry point for the various activities of the conference:

• Keynote presentations – given by knowledge leaders such as Leif Edvinsson of Skandia, Karl Erik Sveiby, and Bipin Junnarkar of Monsanto.

• Workshops – led by subject experts, including Verna Allee18 on ‘Knowledge and self organization’, Etienne Wenger ‘Learning communities: the ecology of knowing’, Arian Ward on futurizing and Michael Rey on creativity.

• Discussion groups such as workplace communities.

• Community Café – more informal discussion e.g. on shared interests, on books we love.

• The Open Space Circle – ‘an open space for participant generated discussions; get first hand experience facilitating a learning conversation … explore questions of most interest to you’.

In the Open Space Circle forty-two discussion items were created, which covered topics as varied as organizational intelligence in family-owned businesses, knowledge artefacts and communities of practice in health care settings. As a result of discussion at the fair, new initiatives have evolved, such as KEN (Knowledge Ecology Network) and the Knowledge Ecology University.

Summary

This chapter has shown the importance of a team as a focal point for knowledge work, a node in an ever changing knowledge network. It has explored the dynamics of knowledge communities. Both teams and communities thrive through a shared sense of purpose and cohesion. High performance comes from integrating ‘soft’ factors such as building relationships and developing trust, alongside team processes and technology.

The twenty-five principles and additional guidelines just described have helped various virtual knowledge teams and communities collaborate more effectively. Are they appropriate for your teams? Yes and no. Yes – they are based on research and experience in teams that perform well and cover the key dimensions that need to be addressed. No - every team is different and will need to develop their own set of guiding principles according to their aims and circumstances.

Of the five groups, it is team processes that are usually the most important. Within team processes, it is the quality of conversations and structured dialogue that most frequently determines the difference between poor and well performing teams. In a virtual environment, moderators play an important role in stimulating this dialogue and thus adding to the knowledge capital of individuals, teams and the organization as a whole.

Action check list

Establishing teams

1 Have you identified the core teams of your business? Is there a directory or index of them?

2 Did Activity 6.2 identify the need for any changes in the organizational context? Develop a plan to make senior management aware of this need.

3 Develop a set of core principles for your team and have them printed and laminated.

4 Develop a set of team performance measures and success criteria that also take account of individual team member’s needs. Review your operating plan against these indicators.

5 Identify your team’s core knowledge inputs, processes and outputs. Ensure that you have assigned responsibilities for key knowledge processes and repositories.

Implementing good team practice

6 Develop a programme of liaison with those teams with which you have the greatest interdependence.

7 Develop a format for team meetings that ensure that sufficient time is devoted to review of processes and for team learning and development.

8 Identify a suitable facilitator external to your team, who can help the team throughout its ongoing development.

9 Identify which knowledge communities can contribute to your team’s success. Ensure that appropriate team members are involved and that they share relevant knowledge within your team.

10 Periodically review your core principles and how well they are being followed.

Notes

1 Originally published as ‘Virtual working’, at http://www.skyrme.com/insights. More recently published in Lloyd, P. and Boyle, P. (eds) (1998). Web Weaving: Intranets, Extranets and Strategic Alliances. Butterworth-Heinemann.

2 Katzenbach, J. and Smith, D. (1992). The Wisdom of Teams. Harvard Business School Press.

3 Buchanan, D. A. and McCalman, J. (1989). High Performance Work Systems: The Digital Experience. Routledge.

4 Belbin M. (1993). Team Roles at Work. Butterworth-Heinemann.

5 Drexler, A. B. and Sibbert, D. L. (1993). The Drexler/Sibbert Team Performance Model. Graphic Guides; a good discussion of this with relevance to global virtual teams is found in O’Hara-Devereaux, M. and Johansen, R. (1994). Globalwork: Bridging Distance, Culture and Time, pp. 157–170. Jossey Bass.

6 Coles, M. (1998). Managers tackle world-wide teams. Sunday Times, 8 March, p 7.24.

7 Kuntz, W. and Rittel, H. (1972). Issues as elements of information systems. Working Paper No. 131, Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California at Berkeley.

8 Conklin, J. (1998). IBIS and organizational memory, at http://www.zilker.net/business/info/pubs/desom.

9 Beer, S. (1994). Beyond Dispute: The Invention of Team Syntegrity. John Wiley & Sons. A more recent write up including practical experiences is Lennard, A. D. (1997) at http://wwww.phrontis.com/TSBackgr.htm

10 Jarvenpaa, S. L. and Shaw, T. R. (1998). Global virtual teams: integrated models of trust. In: Sieber, P. and Griese, J. (eds.). Organizational Virtualness. Simowa Verlag, pp. 35–52.

11 Jarvenpaa, S. L. and Leidner, D. (1998). Communications and trust in virtual teams. Journal of Computer Mediated Communications, 3(4), June 1998 at http://jcmc.huji.ac.il./vol3/issue4/jarvenpaa.html.

12 Conklin, J. (1998). IBIS and organizational memory, at http://www.zilker.net/business/info/pubs/desom.

13 Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations. McGraw Hill.

14 Wenger, E. and Snyder, W. (1998). Learning Communities, Workshop 5, KEFair 98. http://www.tmn.com

15 See for example, Community Intelligence Labs Community Covenant, at http://www.co-i-l.com/oil/iacenter/ccovenant.shtm

16 Lisa Kimball, Moderator Guidelines, at http://freenet.msp.mn.us/confdoc/modguide.htm

17 Knowledge Ecology Fair 1998 at http://www.tmn.com/ksweb

18 Author of Allee, V. (1997). The Knowledge Evolution: Expanding Organizational Intelligence. Butterworth-Heinemann. Arian Ward was Leader of Collaboration, Knowledge and Learning for Hughes Space and Communication; Michael Ray Professor of Creativity and Innovation at Stanford Business School. Etienne Wenger coined the phrase ‘communities of practice’.