Chapter 5

The knowledge

networker’s

toolkit

Your knowledge and skills are your greatest assets. Are you making the most of them? Are you using them to fulfil your ambitions, while leading a balanced lifestyle and avoiding overwork and undue stress? In today’s dynamic environment, where the future is uncertain and job security minimal, those who survive and thrive will be those who take charge of their career. They will understand their capabilities, chart a course for their future, work smarter not harder, and network extensively to achieve their aims. In short, they will be knowledge networkers.

This chapter considers what you as an individual need to do to succeed in a networked knowledge world. Your starting point is knowing more about yourself – your values and what is important to you. You then need to consider how to manage your key activities and resources – work, time, communications, information, your network, technology and your workspace. Last, but not least, you need to focus on managing and developing your intellectual capital.

It is not the intent of this chapter to be a primer on personal development, self-improvement or career planning. There are many books that do that much better.1 The main focus is on those aspects that are inherently different in the networked knowledge economy – virtual working and working with information and knowledge as core resources.

Characteristics of successful knowledge networkers

In an analysis of high-performing knowledge workers, Keeley and Caplan identified nine recurring characteristics:2

1 Initiative taking – they will act beyond the defined scope of their job.

2 Good networkers – they will directly tap into the knowledge and expertise of their co-workers.

3 Self-management – they have good control over their use of time, making and meeting commitments and career development.

4 Effective teamworkers – they coordinate their activities with coworkers and assume joint responsibility for the outcomes

5 Demonstrate leadership – they formulate and state common goals and work to achieve consensus and commitment to them.

6 Supportive followers – they support their leaders in achieving their goals through taking the initiative, rather than waiting for specific instructions.

7 Broad perspective – they see their work in its wider context and take on board the perspectives of other stakeholders.

8 Show-and-tell – they present ideas persuasively.

9 Organization savvy – they are aware of organizational ‘politics’ and negotiate their way around to promote co-operation and get things done.

This shows the importance of broadening your horizons beyond your specific job role, working across organizational boundaries and engaging in teamwork and networking. Job advertisements tell a similar story. Self-motivated people with interpersonal skills, who are achievement oriented, flexible and adaptable are highly sought after. Behaviours and transferable skills are as important as any specialist knowledge. This is understandable. Changing markets, technologies, methods and customer needs means that much of today’s specialist knowledge rapidly becomes obsolete. Adaptability and a capacity to learn and assimilate new knowledge are therefore crucial.

To be a successful knowledge networker therefore requires a range of capabilities as represented in Figure 5.1. The top layer of the inverted triangle represents surface knowledge that is explicit and visible. The deeper you go, the more tacit the capabilities, and the longer it takes to acquire or change them. At the bottom are values and beliefs. These determine our overall approach to life and work, and shape our everyday actions and decisions. They are deep seated and difficult to change. Hence culture change in an organization is usually reckoned to take at least three to five years. Along the right-hand edge of the triangle are shown ways in which these layered capabilities are developed. Notice that training, so widely practised in many organizations, is usually most effective only at the upper layers.

Figure 5.1 Triangle of capabilities

Activity 5.1: Develop your own capabilities triangle

Use your own words to describe your capabilities and specialities. Be sure to distinguish explicit (surface) knowledge and your deeper (tacit) knowledge.

Know yourself

Uncovering your personal values is usually a good place to start. It also gives practice in an important generic knowledge process - that of converting tacit knowledge into explicit. A common approach used by career counsellors is to ask you to think deeply about your past (Activity 5.2).

Activity 5.2: Articulate or reaffirm your core values

1 Think of what you have accomplished and done well throughout your life. Write them down. A timeline is a useful tool for this.

2 Which of these did you also enjoy doing? What particular aspects of the activities did you like?

3 What were the circumstances – working environment, boss, co-workers, personal situation etc.?

You should arrive at five to seven values that are important to you. Commonly found core values for professionals include recognition, autonomy and achievement. Brian Hall, a long-time investigator of values, has identified 117 core values that include duty, respect, accountability, esteem and self-worth.3 Use words and phrases that are meaningful to you. If you have not done this before, it may take considerable effort to really pull out the few really important ones. Discuss your findings with your spouse or a close confidant.

Having ascertained your values, look more widely at different aspects of your personality. Most professionals will have encountered one or more of the many personality profiling techniques that exist. Most involve you responding to a battery of questions about your preferences in different situations. Some involve in-depth personal interviews with trained counsellors. Popular tools are the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTITM)4 and neurolinguistic programming (NLP).5 Among other things, they will help you understand how you absorb information and make decisions. For example you may prefer a logical argument or you may rely on your intuition. You may like visual representations or you may prefer to listen attentively. The point about any kind of profiling is that it reveals individual preferences. Many problems in work situations arise because these preferences are ignored. If you are sensitive to your own and your colleagues’ preferences, you can improve the quality of your communications and develop more harmonious working relationships.

Your thinking style

As a knowledge networker, you spend a lot of time thinking. So it is important to understand something about your own thinking style. One useful tool for this is the Thinking Intentions Profile (TIP) developed by Jerry Rhodes and Sue Thame.6 It is based on research into ‘skilful thinking’, carried out at Philips from 1977 to 1981. By responding to a set of forty-eight questions, individuals can ascertain their preferred thinking styles, which are grouped into three categories coded by colour:

1 Green thinking – Creating what’s new: imaginative, divergent, lateral, intuitive.

2 Red thinking – Describing what’s true: information seeking, classifying, organizing.

3 Blue thinking – Judging what’s right: deciding, forming opinions, evaluating.

Associated with each colour are two modes - ‘hard’ and ‘soft’. Hard represents precision and a scientific approach; soft relates to feelings and an artistic approach. Thus soft green is imaginative, while hard red is analytical. This approach has been further developed by SmartSkills into a set of diagnostic aids and also toolkits for various kinds of professional and management activity, such as task analysis decision-making or strategy development.7

Activity 5.3: Understand your knowledge processing styles

Think about how you absorb information and make decisions. Write down your preferred ways of gaining knowledge. Write down what thinking processes and preferences guide your decision-making. If possible, use a profiling tool, such as one of those mentioned.

As you go through the rest of the activities in this chapter, you will probably find that you need to adapt them to match your style. For example, if you are a green thinker, you may prefer to visualize activities rather than complete written details. Whatever your style, the main consideration is to be conscious and explicit about what guides your actions.

Work smarter, not harder

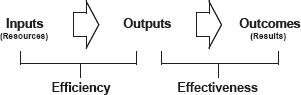

The smart workers focus on outputs and results. They recognize the distinction between outcomes and efficiency and effectiveness (Figure 5.2).8

As an example, your inputs on a piece of work might be information, knowledge and time spent. Your output might be a report. Your efficiency is how quickly you complete it, e.g. measured by number of words per day. Your effectiveness, though, depends on the outcome - what benefits are achieved by acting on your recommendations.

Figure 5.2 The difference between efficiency and effectiveness

Source: Dr B. Farbey, adapted from The Audit Commission.9

Activity 5.4: Goals and effectiveness measures

Take a typical project you are working on. What are its inputs and outputs? What are the outcomes you are trying to achieve? What measures do you have against each of them? Now try to describe them in terms of knowledge, who uses it and how it is transferred and used.

Research conducted by Barbara Farbey when at the London Business School indicates that effective managers and professionals take a holistic view of their situation and simultaneously manage several key resources (Figure 5.3).

In thinking about your work tasks, consider the relative intensity of thinking, information processing and communications. List your tasks and rate them against these characteristics. Also identify what kind of tasks you prefer doing and are better at. Think about which tasks are best done individually and which are best done in teams. Make sure you include personal development activities in your task list, such as learning and developing your network.

Time is a precious resource. Unlike knowledge, which can be reused, time once past is irretrievable. Review periodically your use of time: plan vs actual. Think of what needs doing in different time planning periods - for example a three to five year career period, a six months to one year project period, a month, a week, a day. Develop time planning approaches consistent with your thinking style. Stephen Covey is quite critical of time management systems that concentrate on activities, and suggests a focus on relationships and results. His simple but effective planner distinguishes the urgent from the important and links activities to key objectives.10 Common time traps that knowledge workers fall into are underestimating how long developmental activities take, not realizing how disruptive interruptions are to thinking, and switching context too frequently between different types of task.

Figure 5.3 Factors that need managing well (after Farbey)

Manage the information glut

One of the problems facing many knowledge workers is that of information overload, coping with the growing volume of information that comes your way. A study commissioned by Pitney Bowes revealed that many employees now process over 150 emails a day and that 60 per cent of managers and professionals feel overwhelmed by this volume: ‘today’s corporate staffs are inundated with so many communications tools – fax, electronic mail, teleconferencing, postal mail, interoffice mail, voice mail – that sometimes they don’t know where to turn for the simplest tasks’.11

The problem can even lead to a physical illness known as Information Fatigue Syndrome.12 Current trends point to no improvement in this situation. For every intelligent agent that filters out unwanted information, another is likely to gather you even more! You will therefore need to devise a good personal information management strategy that gives you ‘the right information, in the right place, in the right format, at the right time’ (Figure 5.4).

Your personal preferences and styles will help determine what approach works best for you. Try the following approach:

Figure 5.4 Elements of a personal information management strategy

1 Clarify your information needs. What are your goals, priorities and critical decisions? What information and knowledge do you need to support them?

2 Develop a sourcing strategy. Consider what periodicals or databases you need to scan regularly, and what you can seek out just when you need it. Identify the best content sources, including people, for each of your information needs.

3 Clarify what you want ‘pushed’ at you (e.g. via email) and what you want to ‘pull’ when needed. For which information is it essential to be alerted about changes? Err on the side of ‘just in time’ pull rather than wanting to see everything.

4 Work out how and when you will process information. There are only a limited number of things you can do with incoming information, e.g. use it immediately, file it or throw it away. You may want to use software filters to automatically preprocess incoming electronic information. This turns push into pull. If you don’t need to work on a given folder right now, then that’s an email you don’t yet need to read.

5 Set criteria for what you want to file and save. Why do you want to keep it? For me it is seminal articles, essential reference material and work in progress. For most of the rest, I rely on the Internet and other sources so that I can access what I need when I need it.

6 Create a personal filing system, with a well-designed structure, that is appropriate with your work activities and areas of knowledge. File things away as soon as you can. Don’t leave them in a ‘to read’ pile. For computer held information, use search tools such as Discovery AltaVista or Verity Personal that index all the information held on your personal computer – whether word processed documents, emails or presentations. They are a boon for careless filers like myself.

7 Refine your information. You might, for example, codify information into different categories, e.g. fact, opinions, examples. As you collate it and use it, synthesize key concepts and messages.

8 Review your information on a periodic basis. Prune ruthlessly based on use. Some people tab their files with a colour code the last time they accessed a file. If they don’t access it, they don’t keep it!

As a general rule, the less you keep, the less the overhead of management, or of misplacing information. New information is being created all the time that others, such as database managers and librarians, are paid to index and manage. Why duplicate their effort? Also, don’t fall into the trap of analysis paralysis – seeking ever more information to make decisions. Good thinking with incomplete information is better than poor thinking with too much.

Activity 5.5: What sort of information manager are you?

Review a recent significant project or decision. List what information you felt you needed to do your best, how you went about finding it, how you processed it, and how it affected the outcome of your task. What have you now done with this information and how might you use it again? After reviewing the check list, would you do something different next time you are in a similar situation?

Communicate effectively

Each of us spends a lot of time communicating, but how often do we step back and ask how effective we are at it? Poor communications is often cited as a primary reason for failed projects and ineffective teams. Are you using the best medium for the message? In one study it was found that ineffective media were used in one-third of all business communications.

A good starting point is to understand your preferred style for receiving different classes of communications. You may be a listener rather than a reader. You may prefer to receive graphs rather than tables of data. Make those who communicate with you aware of your preferences. For example, when in a meeting, Bob Wiele and his colleagues at SmartSkills place cards on the table in front of them that show their thinking colours. This immediately gives a visible cue about how they process information. Activity 5.6 can help you gauge your communications patterns and effectiveness.

Activity 5.6: Analyse your communication preferences

Take a short period, say a few days, and for each communication, list who initiated it, the medium used, its purpose, duration/length, degree of interactivity, outcome and comments on effectiveness. Is there a pattern in those communications that were effective and those that were not? Could similar or better outcomes be achieved in less time with different media? Are there people with whom you should be communicating with more frequently but are not?

Review your communications log and determine what communications media and technologies are most appropriate for different types of communications. Consider:

• Content - purpose of communication, type (e.g. request, advocacy), length, precision, degree of formality, security.

• Time – frequency, duration, pattern (e.g. lengthy information vs interactive vs bursts).

• Space – location of recipient, accessibility.

• People – number of recipients, their preferences, role, styles, feedback.

As a result you may elect to use email for most routine communications to minimize the problems of ‘telephone tag’, but initiate regular face-to-face or videoconferencing meetings for project progress reports.

Good communications is fundamental to effective knowledge sharing. It occurs when the recipient clearly understands what the sender intended and acts accordingly. This requires dialogue, not monologue. Here are seven tips for effective dialogue:

1 Plan your messages or conversations beforehand – clarify your purpose, jot down an expected outcome, and note the topics to cover.

2 Make sure the environment is conducive to good communications – reduce background noise, divert incoming telephone calls.

3 Begin by introducing yourself (if not known to the recipient), establish rapport. Make sure that it is an appropriate time to converse.

4 When conveying information, first set the context; start from common ground and what is known. Make one point at a time and wait for feedback.

5 When receiving information listen carefully; don’t jump to conclusions. Practise active listening, play back your understanding and ask clarifying questions (which also gives you time to think and process what you have heard).

6 Summarize, especially action points – this gives time to reflect and confirms mutual understanding.

7 Follow through. Did you commit to an action? Note it in your diary. Failure to keep even minor promises will influence the way that people judge and trust you.

Email and other on-line technologies require even more attention to ensure that communications is effective. Since email is not simultaneous, there is no immediate opportunity to check how well your recipient has understood your message. Here are a further seven tips for improving electronic communications effectiveness:

1 In general, restrict each email to just one topic. This allows the recipient to process each one differently, such as forwarding one to a team, filing in different folders or replying directly.

2 Use meaningful titles. Avoid the standard reply, e.g.’Re: Our Meeting’, when the topic has moved on.

3 Avoid copying all recipients by default. For many emails, replying to the sender alone is sufficient.

4 Reply to emails by making your comments adjacent to copies of just the parts of the received email that are relevant.

5 Keep them short and informal, perhaps add some humour, to reflect a conversational style. Emails are not for essays. If appropriate, send documents as attachments with a covering email.

6 Follow a logical structure – state your purpose, develop your message logically and be clear about what you expect the sender to do.

7 Make use of efficiency aids on your mail software - distribution lists, filters, filing in multiple folders and the use of standard replies.

Spending a little effort in improving the structure and readability of emails that you send, will bring significant benefits to the recipient, and make an overall contribution to the effectiveness of your communications.

Activity 5.7: Your email effectiveness

Take a selection of emails (say five to ten) you have just received. Was the intent of the sender clear? Did you understand what they were communicating? Was it clear what action you should take? Now review a corresponding number of emails you have recently sent.

Beyond email, there are useful techniques of netiquette (network etiquette) for participating in on-line and discussion lists. For example, Rinaldi’s Guide to Netiquette has special sections for email, websites and discussion lists.13

Working on-line in a global context also requires a greater sensitivity to other geographies and cultures. Don’t assume that your home town is the centre of the world, or that other people’s values are the same as yours. Enter an open dialogue to help you discover those with whom you are communicating. This knowledge alone helps richer dialogue later.

Develop your network

Your personal network, which may run to hundreds of people, is the key to leveraging knowledge. Their knowledge can help you, and yours them.

Every person in it is a potential link to many more. Your network is dynamic. At different times different people are closer to you, both intellectually and emotionally, than others. Your network needs active managing. Review the following points to consider how you might manage it more effectively:

1 Understand the extent and shape of your network. With whom do you have the closest relationships and most regular contact? Draw a network diagram, with a circle representing you at the centre, surrounded by two to three concentric circles representing closeness to you. Draw links that show the nature and frequency of communication. What needs to change?

2 Determine how its composition might be strengthened. Is there other knowledge that you need access to? Are there others who can help link you to influential people or new business opportunities? Ensure that your network has a good mix of different thinking styles, generations, organizations and people with different cultural perspectives. It may seem difficult and uncomfortable but diversity strengthens your overall capabilities.

3 For your closest network associates, do you really know what motivates them? Find out about their plans and aspirations. Then you can help and support them. Too many business meetings get bogged down in task detail, ignoring these simple questions whose answers might well help the task proceed.

4 Keep activating your network. If you have not been in contact with an important member for some time, make a point of communicating with them. Some people work through their contact base, say twenty names a week, throughout the year. A short call asking:’ How are you? What are you doing? Can I be of any help to you?’ is all that it takes. Don’t just call when you need help.

5 Engage your network in your activities, even if you could do them by yourself. For example, on nearly all my consultancy contracts, other than the very smallest, I actively team up with a colleague. This helps strengthen the relationship, as well as giving backup should I fall ill.

6 Reciprocity and trust are the watchwords of effective networking. You get out what you put in. Use the game theory principle of tit-for-tat that has been shown to be effective in many business situations. You respond as they behave. Start off positively. Be proactive and helpful, and a good networker will respond in kind. If they do not, nudge and encourage them, but if that fails, then abandon them. If they take advantage of you in some way, send a strong signal to them to make amends. Be fair but clear. You only want people in your network who give as much as they get.

It is also useful to cultivate as part of your network people not directly involved in your work, in order to provide other kinds of practical or emotional support. Finally, a social network should be warm, friendly and informal. Therefore, you should create opportunities to meet in a relaxed setting, say on a boat trip or at a barbecue.

Activity 5.8: Deepening your network relationships

For each person in your inner network, check your diary to see when you last had an informal ‘getting to know you better’ session with them, that lasted two hours or more. If it was more than three months ago, schedule such a session.

Be techno-wise

Information and communications technologies are your vital tools. To maximize your effectiveness, you need to choose them with care and mould them to your individual situation. The technology check list draws together some key selection principles, first through some key considerations (1-5), then through a decision and implementation process (6-10).

A typical basic product set for a knowledge networker consists of a high-specification multimedia personal computer plus telecommunications equipment and services. The computer will have generic office software (word processing, spreadsheet, presentation software etc.) and may have personal or shared peripherals such as a printer, scanner, videoconferencing camera.

As you tailor technology to meet your needs, you will be faced with multiple, often conflicting, choices. Do you need a desktop PC, a notebook, a palmtop PC or some combination of all three? Think about where you work and the complications of synchronizing files if you use more than one computer. Should you go for multifunction devices that combine fax, scanner and printer in a single package, or have separate devices? A general rule of thumb is to choose combined functions where saving money and desk space is important, but to go for separate devices where you need higher performance. In all the choices you have to make, the essential first thing to do is be clear about how you work and what functions are most critical in leveraging your effectiveness.

Whatever the choice of technology the most important practical considerations concern how you use it. With communications technology you need to have an explicit call handling strategy. When and where will you divert incoming telephone calls? Do you want to give callers a single number rather than separate office, home and mobile numbers? Be conscious about security and loss of data. Although portable computers are vulnerable to theft, more data is probably lost by inadequate backup procedures that are only discovered when your hard disk crashes or you accidentally delete important files.

1 Organizational context. Are you located with co-workers or part of a virtual team? Are there company standards and constraints? How soon might your work or co-workers change?

2 Task analysis. What is your pattern of ICT for communications, document work, specialist applications, Internet etc.? What is personal and what is shared?

3 Location/workplace considerations.Where do you work? How fixed or variable are your work locations? Is the locus of your work your office, home, somewhere else or location independent?

4 Personal needs and working style. Are you a technology enthusiast or pragmatist? What is your tolerance level of new technology?

5 Critical success factors. What are the key aspects of communications, information and knowledge, and other uses of ICT that are important for your success?

6 Your basic product set. Select a basic combination of products and services that makes a sensible base for tailoring and adapting to your needs.

7 Specific product selection. From catalogues of products and services, apply selection criteria to guide you in selecting the most appropriate options.

8 Holistic review. Check that the solution selected meets your needs ‘in the round’ and is sufficiently well integrated i.e. that each component works well with the others.

9 Clarify supporting mechanisms. How will technical support, backup and security be provided?

10 Continuous improvement. Gain proficiency in the use of the products and services. Devote time for learning and practice.

As your work becomes more virtual and location independent, there are a number of products and services that you need to seriously consider:

• Cordless (DECT) phones for mobility around the office.

• Telephone charge cards, that for the world traveller often give cheaper and more reliable access than mobiles.

• Adaptor kits containing essential power plugs and telephone socket converters for round-the-world connectivity.

• Audioconferencing. Often regarded as the poor step-cousin of videoconferencing. However, it is more universally available, quicker to set up when away from the office and lower in cost.

Activity 5.9: Does technology work for you?

Consider how extensively you use technology in your job. Does it make your work easier? If not, why not? What functions do you find you use the most frequently? Can you upgrade the technology to do these better? What technology causes you the most problems? Are there improved solutions?

Manage your workspace

Most professionals devote insufficient attention to their office environment. Yet it can have a profound effect on productivity. If you have control over basic conditions such as temperature, air flow, ventilation, lighting and outlook, you are more likely to work efficiently. Ergonomic studies show the importance of good posture and seating when using computers workstations. Indeed there are now EU regulations and guidelines governing visual display unit (VDU) usage. Screens should not reflect glare from windows or lights, eyes should be level or look downwards to the screen, and wrists should have a surface to rest on in front of a keyboard. All this is fairly basic, but often ignored. Likewise, layout should allow you to move easily from one work area to another.

For knowledge work, space in which to think and space in which to meet are two important work areas. The former should be purposeful, and the latter inviting and informal. If your office does not let you do this, invest in an easy chair and low table, and do it whatever the corporate facilities policies! Choose colours that stimulate the right mood. Make sure that your office has a range of environments to meet your various needs and moods. Many conventional offices are lamentable for purposeful knowledge work.

If you work at home, there are other factors to consider as well. Ideally, you should have a separate room devoted to office work. Make sure you have sturdy furniture and sufficient work surface and storage space. It’s amazing how space for those office essentials, like stationery, mounts up when you just cannot walk round to the office stationery cupboard! Unlike an office where you are likely to get up and walk around a lot to meet colleagues and have meetings, at home you may be sitting in your chair for longer periods. Therefore an ergonomic office chair, with lumbar support and plenty of adjustment, is a wise investment. Finally, do not overlook important safety equipment, including two fire extinguishers, one dry powder and one for electrical fires. Insurance, planning regulations, employment contracts and taxation matters are other practicalities that home workers, whether self-employed or corporate employees must also address.14

Personal development

Knowledge and intellectual capital need constant updating and refreshing to maintain their value. As with thinking styles you will have your own learning style and preference. A well-known model is that of Honey and Mumford.15 Individuals use several modes of learning but tend to have a dominant mode based on one of the following four learning styles:

• Pragmatist – acts quickly, learns by doing.

• Activist – learns through concrete examples and experience.

• Reflector – observes, takes in multiple perspectives.

• Theorist – conceptualizes, integrates observations into their mental models.

Each represents one part of a typical learning cycle – planning, doing, reviewing, understanding. Once you understand your preferred learning style, take practical steps to introduce learning activities into your timetable. The more these can be made part of your daily work, the easier it is to get into the habit of continuous learning. For example, if you are a theorist, make sure you have time to read and put your activities into conceptual frameworks. If you are more of a pragmatist, pick activities that will give you practice at a skill you need to develop.

There are five keys to continuous learning:

1 Identifying a learning need.

2 Developing a learning event.

3 Identifying learning resources.

4 Scheduling time to do it.

5 Making time to review and to practice.

And this process repeats itself for every part of your knowledge and skills base. Learning events need not be long – ten minutes is often ideal. Your learning resources could be other people as well as printed or visual material. A week or so after a learning event, review it and record how well you learnt.

There are various tools and techniques that can help you learn as you work. One is active note-taking. Ignore presenters when they tell you not to take notes because there are handouts. Research shows that retention levels jump from 10 to 30 per cent if you write something down rather than just listen, and increase even more if you subsequently present or practise what you have heard. In a similar vein, don’t be afraid to make copious notes in publications that you read, even books. Such notes, representing your own interpretation and reference frame are often more useful than the original document.

Activity 5.10: Developing a learning plan

Select one or two areas of knowledge that you need to develop.What is the best way for you to develop this knowledge - through a course, through hands-on experience, through knowledge exchange with a member of your network? Now schedule a specific time slot within the next month to accomplish it.

Another underrated but very practical tool is a learning log. Just as organizations capture and share lessons as part of their knowledge management, as an individual you can likewise benefit from learning from your daily experiences. A log book helps you learn in a systematic way.

Creating a learning log

In a hard-backed notebook, draw a line across each page about three-quarters of the way down. Divide the part of each page above this line into three columns headed ‘Margin’, ‘Main text’ and ‘Ideas/actions’ respectively.

The central column is for your regular note-taking. In it make sure that you highlight outcomes. Use the margin column for topic subheadings and navigation pointers. These may only emerge later in a conversation or meeting. Use the right-hand column for three Is - Ideas, Implications and ‘I will’ (actions). Again, some may not be added until later when you review your notes. Actions may be requests by others or self-initiated. A reason for separating them into this column is to give quick visual record of how much time you might be committing.

The bottom part of the page is your review and reflection section. Record here what you have learnt. Did outcomes happen as planned? If not why not. Note what would you do different next time. Also add feelings, thoughts, and ideas for doing better next time.

Revisit these pages regularly, looking for patterns and adding further reflections. A log book used in this way becomes more than a record of your activities and meetings. It becomes an active tool where each page is a contribution to your growing intellectual capital.

As you may have already discerned, despite my very intensive use of computers, my own diary, time planner and learning log books are in fact kept on paper. They are with me almost constantly and available for instant reference.

Activity 5.11: Recording your intellectual capital

Itemize the main items of intellectual capital you have, Using Table 5.1 as a guide. For each write down (e.g. in six columns) who might it be valuable to, its current value, how this is likely to change if not updated, how it could be made more marketable and valuable, and how you could leverage this value.

Your intellectual capital

As part of your career planning, you have probably already documented your skills and experience in a CV. A review of your intellectual capital takes this a stage further. You explicitly record your intellectual capital (IC) in different categories. The customer, structural, human capital model outlined in Chapter 2 can form a good basis. This is expanded in Table 5.1 from an individual perspective.

Table 5.1 Categories of personal intellectual capital

| Human (competencies) | Experience (applied knowledge) | Accomplishments, successful situations |

| Knowledge Skills | Professional fields, industries, markets Technical, professional, IT, on-line, transferable skills | |

| Structural | Processes Network | Methods you have developed, refined Know-who, your contacts, the IC you can mutually leverage Information resources Your personal databases, files, codified knowledge, articles |

| Customer | Relationships | Number and depth of your personal customer relationships |

| Reputation | Successful assignments, projects; credentials based on experience | |

| Other | Any other IC that has value if exploited, e.g. copyrights, designs. | |

By developing an inventory along the above lines, you start to gain a perspective of your important personal assets and how you might develop and exploit them. Typically you will find that your structural capital is low. Concentrate on converting more of your other forms of capital into this more explicit form. As the knowledge economy develops, there will be more ways for you to make such explicit knowledge tradable, for example through knowledge exchange networks or knowledge markets, such as those described in Chapter 10.

Leveraging your intellectual capital

As a knowledge networker you must both grow and exploit your intellectual capital. This requires a certain amount of self-marketing and influencing others. Selling yourself and your knowledge is an intangible sale. You cannot package and market it like a soap powder, nor would most professionals want to. The key is to let your reputation attract people to you. This can be done as follows:

• Presentations at internal seminars and external conferences.

• Writing ‘white papers’ or ‘thought pieces’ that provoke discussion among your peers and managers about critical business issues.

• Publishing in journals, periodicals and your professional and trade press. Paradoxically external publication is often a good route to better internal recognition. It shows that the outside world values what your write.

• Making your experience known in directories and databases. If your company’s knowledge base has an expertise directory, make sure you are properly represented in it.

• Active contribution to subject matter discussion lists or databases.

• Creating your own web page, even if it a personal page within a company’s intranet. Focus on what you know and how it helps your reader, rather than satisfying your ego.

• Public relations. Be willing to be interviewed for press, radio, television or video, including your organization’s newspapers or videos.

• Create short ‘how to … ‘ guides. Do it in such a way that the reader knows that what they are reading is just the tip of your intellectual iceberg. Beneath it you have a lot of tacit knowledge waiting to surface!

This is how you package and present yourself to the wider world. Your selling proposition must be clear on how others can take advantage of your knowledge. This means articulating how you will transfer it in a given situation. Are you a facilitator, whose skill elicits the sharing of knowledge by others? Will you package your knowledge in the form of training or workshops? Will you act as a mentor and learning resource to others? Whichever mode is best for you, the linchpin of your proposition is to specify how your skills and knowledge can improve organizational performance. Your intellectual inventory should provide illustrative examples. And as you complete a successful project, remember to add it to your inventory!

The millennium manager

Some of you will be taking the management career path. In the knowledge economy the role and skills of managers is different. Most will manage knowledge workers who know more about a subject than they do. Their role is one of managing the context and environment so that knowledge workers are motivated and work well in a team. Research by Martin Tampoe identified three primary motivators, other than money, as common amongst knowledge workers - personal growth, operational autonomy and task achievement.16 Managers must therefore create business challenges and personal development opportunities to satisfy these motivators. They must provide positive feedback and create a sense of community. They must also create events and situations that facilitate socializing and joint learning activities. Some of the shifts contrasted with conventional management styles are:

• Telling how → telling what: prescribing the outcomes, not the methods.

• Controller → coach: helping workers learn as they carry out their tasks.

• Directing → enabling: giving workers autonomy but supporting them as needed.

• Input measures → output and outcome measures: managing by results.

• Detailed measurement → motivation: enthusing with vision and encouragement.

This is a more hands-off and strategic style of management. Individuals are empowered to manage their day-to-day activities. More than ever, managers will succeed through ‘soft’ interpersonal skills and especially communications skills. Networking is also a key success factor. In a study by Fred Luthans of 400 managers over a four-year period, successful managers spent 48 per cent of their time networking, compared to other managers where the figure was only 8 per cent.17

As companies globalize and virtualize other key capabilities are being able to work across international borders and having cultural sensitivity. In many multinationals today it is unlikely that individuals will reach higher levels of management without having gained experience in several countries.

The knowledge leader

In the new millennium, successful organizations will need leadership, and in particular knowledge leadership, throughout the organization. Leadership is more than management. It is about vision, creating the future and motivating others to succeed. Knowledge leaders help their companies to succeed through exploitation of knowledge. Successful knowledge leaders, according to research,18 are:

• Challenging – they challenge the status quo.

•Visionary and inspiring – they have a vision of how knowledge could transform their enterprise.

• Clear communicators – they have simple messages, reiterated in many different ways; they use anecdotal examples to inspire.

• Involved – they participate in teams, network extensively, build relationships and attract support.

• Leaders by example – they get involved personally and start experiments.

• Learners – they have a thirst for new knowledge; they learn from both successes and failures.

Many of these attributes are the same as for successful knowledge networkers, though with greater emphasis on nurturing and developing human resources rather than information or knowledge resources. Therefore, knowledge networkers who build up their capabilities and effectiveness through applying the lessons of this chapter are ideally placed to be the knowledge leaders in the successful organizations of the future.

Whichever path you choose, if you have followed the activities in this chapter and devoted time to your personal and emotional development you should be well placed to face the future with confidence.

Check list for action

Analysis and envisioning

1 Understand yourself. Take various profiling tests and clarify your values, goals, and needs.

2 Consider what aspects of your domestic, social and business environment, help or hinder your progress towards your goals.

3 Review your effectiveness. For each of the factors of the effectiveness model (Figure 5.3) rate your effectiveness on a scale of I (poor) to 5 (excellent).

4 Rate your achievements and progress on your on-line capabilities, your intellectual capital inventory, your learning goals/diary and your self-marketing.

5 Taking account of your values and personal preferences, describe your ideal working environment and type of work.

Optimizing your working environment

6 Compare this ideal environment with your current situation. What needs to change and what do you plan to do about it?

7 Prepare a timetable for filling in the critical blanks in your analysis of items 1–4.

8 Review your information management, communications and technology. List five specific areas for improvement e.g. a new practice, new software or training, and schedule into your timetable for the next month.

9 Select a mentor from your network. Arrange a meeting specifically for the purpose of gaining feedback on your approach to the topics addressed in this chapter – understanding yourself, improving your effectiveness, developing your skills and knowledge.

10 Plan your next career move. How different a job or environment is it to what you are doing now? What knowledge and expertise will you exploit? What will stimulate the move? When?

Notes

1 Examples of books covering this area include Pedler, M., Burgoyne, J. and Boydell, T (1994). A Manager’s Guide to Self-Development. McGraw-Hill; Bolles, R. N. (1998). What Color Is your Parachute: A Practical Manual for Job-Hunters and Career Changers. Ten Speed Press; Covey, S. R. (1992). The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. Simon & Schuster.

2 Kelley, R. and Caplan, J. (1993). How Bell Labs creates star performers. Harvard Business Review, July–August, pp. 128–39.

3 Hall, B. P. (1994). Values Shift. Twin Lights.

4 Myers, I. B. (1993). Introduction to Type. Consulting Psychologists Press

5 NLP was developed by Richard Bandler and John Grinder in the 1970s. Bandler, R. and Grinder, J. (1981). Frogs into Princes: Neuro Linguistic Programming. Real People Press provides a popularized introduction. Further resources can be found at http://www.nlpresources.com

6 Rhodes, J. and Thame, S. (1998). The Colours of Your Mind. Collins.

7 The full TIP and other material is available from SmartSkills, Collingwood, Ontario. See http://www.smartskills.com

8 The concepts in this section are based on an unpublished study on ‘Professional effectiveness’ conducted by Dr Barbara Farbey when at the London Business School.

9 Audit Commission (1986). Performance Review in Local Government: A Handbook for Auditors and Local Authorities. HMSO.

10 Covey, S. R. (1992). Habit 3: put first things first. In The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Simon & Schuster.

11 The Institute for the Future and the Gallup Organization (1998). Workplace Communications in the 21st Century. Pitney Bowes. See http://www.pitney-bows.com/pbi/whatsnew/releases/messaging_1998.htm

12 Reuters Business Information (1997). Dying for Information? A UK and worldwide investigation conducted for Reuters, in which 41 per cent of respondents felt that they suffering from information overload. A survey a year later (1998), Glued to the Screen, showed that 61 per cent were feeling information overload, with 80 per cent believing it will get worse before it gets better.

13 Rinaldi, A. H. (1996). The Net: User Guidelines and Netiquette. http://www.fau.edu/rinaldi/net/index.html

14 Various telework associations provide useful guidelines on these matters. See for example The Teleworking Handbook (1998). TCA. This is also published in several national editions in different langauges.

15 Honey, P. and Mumford A. (1992). The Manual of Learning Styles. Peter Honey Pubications.

16 Tampoe, M. (1993). Motivating knowledge workers. Long Range Planning, 26(3), pp. 49–55.

17 Luthans, F. (1998). Successful vs effective real managers. Academy of Management Executive, 2(2), pp. 127–132.

18 Skyrme, D. J. and Amidon, D. M. (1997). Knowledge leadership. Creating the Knowledge-Based Business, ch. 3. Business Intelligence.