Chapter 4

Virtualization:

networking

knowledge

globally

Virtualization exists in many guises. It happens where workers communicate through a computer network to distant co-workers as part of a virtual team. It happens in a virtual organization whose participants come together temporarily to meet a specific market need. Or it may be any one of a number of similar practices that replace conventional arrangements with new virtual forms. The megatrends identified in Chapter 1 are also factors in creating an increasingly virtual world. Globalization and networking lead to greater collaboration between widely separated business units and organizations, while advances in ICT make this easier to do cost-effectively. The restraints of time and geography that have traditionally influenced how we work and trade are rapidly diminishing.

Opportunities through virtualization come through reconfiguring activities in space, time and structure. After considering these three dimensions this chapter describes specific types of virtualization, including virtual products and services, virtual working, virtual organizations, teams and communities. It concludes with some perspectives of knowledge-based opportunities that exploit virtualization.

Three dimensions of virtualization

It may seem paradoxical that knowledge networking requires people to work closely together to share and combine their knowledge, yet virtualization usually means that they are physically apart. A partial answer to this conundrum is that improved global communication allows knowledge networking on a much wider geographic scale than was previously possible. The cost of communicating electronically is usually only a small fraction of that for face-to-face contact, even for people who live in the same locality. Location is one of the three key dimensions of virtuality (Table 4.1). Any organizational strategy developed today that does not fully consider how to exploit these dimensions is unlikely to be sufficiently stretched or secure.

Table 4.1 Dimensions of virtualization

| Location (space and distance) | Local → Global Global → Local Distributed → Centralized Concentrated → Dispersed Physical → Virtual Fixed → Flexible |

| Time | Synchronous → Asynchronous Specified → Flexible Limited hours → All hours |

| Structure and processes | Sequential → Parallel Procedural → Object oriented Aggregated → Dispersed Stable → Dynamic Hierarchical → Networked |

Rethinking location

In the networked economy global becomes local and local becomes global. Individuals can more easily seek jobs or work opportunities outside their immediate locality. A freelance graphic designer in Finland, for example, supplies his services to me in Newbury, England, with a quality and level of service as good as any I could get locally. You can buy products over the Internet, where your shop is a mouse click away, yet may be located the other side of the world. At the same time that the Internet opens up global opportunities, it also means that remote suppliers can compete with you in your local markets.

Surprisingly the Internet can also help strengthen local communities. When a local community in Lapland went on-line it had the twofold effect of building a greater sense of community in isolated villages, while at the same time allowing them to participate in the global economy.

Location can also be exploited by dispersing previously centralized activities into different locations, taking advantage of where the best expertise is available. In 1990, Digital created an award winning disk drive by distributing the development across seven specialist design teams, working in Israel and the USA. Conversely, many organizations have replaced distributed customer response points with centralized telephone call handling centres. When you call a local Dell support number in Europe, your call will most likely finish up being answered from Ireland by a knowledgeable person speaking your language.

The location of an activity does not have to be discrete as in a call centre. Activities can be chunked and dispersed in a myriad of ways. Intelligent networks that automatically reroute calls, even to teleworkers at home, offer organizations much more resilience and flexibility in the way they operate.

Many activities can now substitute physical presence with so-called ‘telepresence’, where tasks are carried out over a communications or computer network (Table 4.2).

Although lack of personal contact limits tacit knowledge exchange, telepresence offers significant advantages over its physical counterparts. Travel can be reduced or avoided altogether by using electronic communications. You can attend meetings virtually through video links. You can use computer conferencing for meetings that might not otherwise take place because of scheduling difficulties. An added advantage of such virtual meetings is that they encourage contributions from those who are more reserved in face-to-face settings. Participants can also make considered responses, rather than making off-the-cuff remarks. As audio and videoconferencing continue to improve, limitations compared to face-to-face interaction will continue to diminish.

Table 4.2 Replacement of physical presence with telepresence

| Conventional | Telepresence |

| Face-to-face conversations | |

| Meetings | Videoconferences (live) |

| Computer conferences | |

| Document exchange, post | Electronic file exchange |

| Retail shopping | On-line shopping |

| Accessing information in libraries | Database access |

In practice, most work activity is best conducted through a mixture of both physical and telepresence. The optimum balance will vary according to circumstances, business needs and personal preferences. For example, most workers in virtual teams cite the positive benefits of having a face-to-face meeting early in its development, so that team members can get to know and trust each other in person before working virtually.

Time shift and reduction

Many information-based activities can take place virtually without incurring the time delays inherent in their physical alternatives. A message sent to the other side of the world by email arrives at its destination in minutes rather than the days taken by post. Electronic wallets can transfer funds without the delays built into the conventional banking system.

Many knowledge-based activities that have traditionally needed simultaneous action by two people can be replaced by asynchronous activities over networks. Each individual carries out their part of the interaction at a time (and place) convenient to them. Despite how it might at first seem, email or voicemail is often quicker than the telephone to complete simple communications. The reason is the avoidance of telephone tag, in which two people wanting to converse keep calling each other without making contact. Email also has the added advantage that messages can be more easily forwarded and duplicated.

The ability to communicate and store information synchronously creates opportunities to use time flexibly. Many teleworkers, for example, adjust their working days around their domestic needs and personal preferences. They may intersperse work and domestic activities, such as doing a few hours work, then taking children to school and the dog for a walk, going shopping, then resuming work later on.

Along with rising customer expectations, businesses are increasingly open twenty-four hours a day. When some supermarkets in the UK started all night opening, they found stores as busy at 2 or 3 a.m. on a Saturday morning as on a typical weekday. An on-line store never closes. It may not be staffed continuously, but this matters little if customers can browse, select goods and place orders. More time critical responses can be handled virtually by service representatives in those parts of the world where it is normal working hours. Businesses need to think of creating twenty-four hours a day channels to knowledge - to people as well as databases.

Different time zones can be exploited in the growing practice of ‘sunshine operations’, such as moving design work around the world according to time zone. When European engineers go home at the end of their working day, the designs are transmitted electronically to the Far East, where in turn they are transferred to the West Coast of the USA. The work on a project never stops, and the time-to-market for a new product or a project is shortened.

Flexible structures and processes

The third dimension of virtualization involves the reconfiguration of organizational structures. Because of physical limitations, many work processes are serial, with work being passed from one person to another in sequence. The use of shared knowledge repositories makes it possible to perform activities in parallel. Thus, marketing, engineering and commercial department personnel can simultaneously work on the same bid proposal document. As various sections are completed, the collaborative document evolves. Boeing and its various subcontractors designed the 777 aircraft frame on a shared computer-assisted design (CAD) system, and so reduced the time normally needed to move paperwork and drawings from stage to stage.

These examples also illustrate the trend of thinking from a process perspective to an object one. The objects in these cases are documents or design specifications. Hoffmann La Roche specifically selected documents as the focus for improving its performance in the clinical trials approval process for new drugs. It uses document prototypes, very skeletal at first, as focal points for the ongoing assembly and evaluation of the required information and knowledge.

Other restructuring opportunities result in virtual organizations or virtual teams. In markets that are dynamic and knowledge intensive, advantages can be gained by more frequent reconfiguration of supply chains than is usual in relatively static markets. Different suppliers can be selected according to their specialist knowledge to create product customization, or for their local knowledge and service capabilities. Management consultancies face different problems with each new customer assignment and rapidly assemble new teams from the pool of available talent.

Many specialist publications work in a way that combines two of these concepts - flexibility of structure and object orientation. The German magazine Teleworx reconfigures its virtual team for each issue, using specialist freelancers knowledgeable in the themes to be covered in a particular edition. The object, in this case the publication, is where the different streams of knowledge are converted into words and images that coalesce into the final document. Few of the journalists, working virtually, have ever visited the magazine’s office.1

Virtualization recipes

The move to virtualization has been developing rapidly over the last few years and has attracted a corresponding vocabulary. Indicative of this are book titles like The Virtual Corporation2 and Virtual Communities.3 Both are incidentally highly thought-provoking visions of the future, but draw on practices that are already visible today. Like any knowledge recipe (see page 63) there is an endless number of ways in which the variables of Table 4.1 can be combined. Organizations who think creatively about them can significantly change the dynamics of their markets, as several of the examples described shortly demonstrate. Activities that are mostly likely to yield strategic opportunities through virtualization have the following characteristics:

• High information handling content (e.g. market analysts).

• Intensive telephone work (e.g. telesales).

• Extensive travel (e.g. salespeople, field engineers).

• Large numbers of client site meetings (e.g. consultants).

• Creative and analytical work (e.g. writing).

Some of the different ways in which organizations can create opportunities from virtualization are now considered.

Virtual products and services

There is rapid growth in the volume of products and service being both virtually over electronic networks. On-line sales are more than doubling every year and are expected to surge to over $300 billion a year business-to-business and $20 billion or more to consumers by the year 2002. Even so, this will still represent less than 10 per cent of all consumer sales and be less than sales made by telephone. Electronic commerce is bringing about these changes:

• On-line marketing of traditional goods and services - travel, computer products, books and gifts are the most highly traded products. Computer maker Dell now generates sales of more than $5 million a day from its website. Small specialist suppliers particularly benefit. Climb Limited, a supplier of outdoor equipment, did as much business in its first year online as one of its shops, at a fraction of the overhead.

• The marketing and delivery of information based goods - business information services and publications are often now sold only in an on-line format, not hard copy. The encyclopaedia Microsoft Encarta on CD-ROM with on-line updates has totally transformed a business once dominated by suppliers of voluminous tomes, such as Encyclopaedia Britannica, costing up to a hundred times more. Potential purchasers can also sample goods before purchase. Many CDs sold from CDNow’s website have segments for sampling. Much software is already delivered by downloading over the net.

• Emergence of new information and knowledge products - virtual flowers and greetings cards makes it easier and cheaper to show that you are thinking of relatives and friends in distant parts of the world. Dispensing on-line advice is a growth industry. Customers who may be reticent or overwhelmed by a face-to-face visit to a professional quite happily share their problems with on-line lawyers and doctors. New knowledge providers like Bright act as packagers and outlets for specialized knowledge, either in the form of information or on-line master classes or consultancy sessions.

• The creation of electronic markets - the Internet has seen the rise of online shopping malls and on-line directories, providing single points of entry to supplier’s websites or actually handling transactions on their behalf. Some, of which Barclaysquare was an early example, that merely emulated the physical retail mall in an on-line format but with fewer goods, have had limited success. In contrast, those that have specialized in niches or have exploited the characteristics of the medium such as Auto-by-Tel have prospered. There are now also on-line auctions, which widen the access to potential sellers and buyers, in everything from cattle embryos to secondhand yachts. eBay has over a thousand categories of goods in its classified sections, in which potential buyers bid against each other.

Many of these developments are driven by lower costs of doing business and increased geographic access. Many on-line transactions, such as issuing tickets or processing an order, cost a tenth or less of conventional ones. Cisco, a supplier of computer networking products, reckons that it saves it over $250 million a year by Internet trading.4 Even these benefits are insignificant compared with what can be gained by developing and exploiting knowledge from such transactions.

Knowledge enrichment

As organizations embrace Internet commerce, their strategies evolve through several stages, each one deepening the customer relationship and increasing their capability to exchange and absorb knowledge. Many start by putting existing literature on-line. This ‘brochureware’ often creates delays in downloading large images and provides little useful content for prospective purchasers. Many organizations compound the problem by making it difficult to communicate with them through their website. They omit email addresses, and many that are given route enquiries to ‘webmasters’ and not to knowledgeable sales staff.

Intelligent catalogues provide more knowledge exchange. Saqquara, as used on Xerox Computer Products web pages, guides users through product choices that meet their application needs. Tracking users’ needs and interests also provides useful knowledge to suppliers. Either through individual profiles, typically gained through a registration form, or by monitoring what information users access, suppliers can generate customized offers or links to further information on-the-fly. Suppliers can get closer to customers by cutting out the intermediary. Unilever provides consumers with advice on perfumes. This helps engender brand loyalty and also gains useful consumer feedback. Marshall Industries, a supplier of electronic components, appeals to its main influencers, electronic design engineers, by providing over 300 000 data sheets on its website.

The ultimate dream of many marketers is the segment of one, where the supplier knows each customer intimately. One of the most cited successes of on-line trading, bookseller Amazon.com, exemplifies relationship knowledge in several ways. Not only does it offer more titles (over 2 million compared to 100 000 in a typical large bookshop) but it also holds much more information and knowledge on-line than is found in a typical book store. It shows readers what other titles purchasers of a given book have also bought. It provides on-line reviews, both from established reviewers but also other customers. It can also inform customers by email when new books are published by their favourite author. Combined with discounts and good customer service, it has built a loyal set of customers in just a few years of existence.

Effective on-line marketing focuses on information needs and knowledge exchange. It provides buyers with the knowledge they need, knowledge that is often sadly lacking when buying conventionally through a shop, where much depends on the knowledge of the particular salesperson you encounter. On-line, the best available corporate knowledge can be aggregated. Consumers can visit more stores in a given time, and shop for the best information and prices. They can compare notes with each other in specialist forums. The successful on-line marketer will link into these and other independent knowledge hubs. They will also make their own on-line presence informative and engaging, so that the customer maintains a dialogue that continues to enrich their market, customer and relationship knowledge.

Telework

The second example of virtualization is that of virtual working or teleworking. Telework has attracted interest since the early 1980s, when Jack Nilles coined the term telecommuter, a person who commutes to work via telecommunications and not travelling. Despite popularization by writers like Francis Kinsman,5 the practice really started to take off only with the widespread adoption of notebook computers and mobile telephones. Today, a number of different arrangements are considered as telework (Figure 4.1), with the teleworker whose base is their home and who only occasionally goes into the office being the minority.

The most common situation is where a person works some of the time from home and the rest in other locations, not just their base office but also customer sites. Another common arrangement is that of the telecentre, known in more rural areas as a telecottage. It is a managed office facility where you can rent workspace, computing equipment and Internet access. A recent phenomenon is the growth of resort telecentres that promote themselves as places to combine work and leisure. For example, Crete Resort Offices provides both business centre accommodation and telework facilities from a local luxury hotel. Office services include bilingual secretaries, email and messaging services: ‘You do not need to bring a thing. Not even a paper-clip.’

Teleworking offers many advantages. For individuals, the top three advantages are personal productivity, reduced commuting time and better quality of personal life.6 It also allows them to carry on working, even after a family house move or the arrival of a baby that needs looking after.

Figure 4.1 Different types of telework

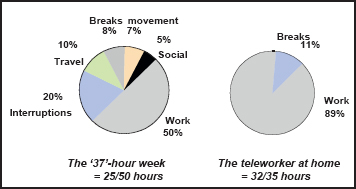

Figure 4.2 Relative productivity of office and home workers

Their employer also gains by retaining their knowledge that would otherwise have been lost. Other benefits for employers are:

• Savings in office space and costs. Most teleworking schemes reduce the space required for a given number of workers by 30 per cent or more.

• Increased productivity. Various companies have reported savings of 40 per cent or more.7 Audits conducted by the author at Digital8 indicate how a thirty-five hour week at home can be much more productive than a thity-seven-and-a-half hour week in the office, since teleworkers avoid travel time and the interruptions of an office environment (Figure 4.2).

• Avoidance of relocation costs. People can change jobs and work together without having to move home, a typical saving of $50 000 or more.

• Less absenteeism. Teleworkers usually take off less time for illness, partly since they may carry on working at home whereas they would spreading germs in an office.

• Access to new sources of skill. For example, the KiNET project in the Grampian region of Scotland, has illustrated the cost-effectiveness of using local skills to outsource CAD work from the home counties.9

• Organization flexibility. As companies restructure or projects change, individuals can continue to work virtually without relocating to another office.

• Resilience. An organization that works flexibly is more resilient to unexpected events (e.g. travel strikes) or disasters (fires, terrorist bombs). Digital’s business continued with minimal interruption after fire destroyed its main Basingstoke office in 1991.10

Despite the advantages, uptake of telework is relatively low. It is estimated that fewer than 2 per cent of Europe’s population telework, although the actual figure may be higher due to the prevalence of informal teleworking by individuals outside formal programmes. One of the most recurring survey results is the desire of individuals to telework. For example, the TELDET study showed that 40 per cent of Europeans would like to telework, if only their organizations would let them. The question asked most frequently at the European Telework On line website is: ‘how can I get work as a teleworker’?

There is clearly a large latent demand by individuals. So why, despite the business benefits, are organizations not more enthusiastic? The number one reason, according to various surveys, is the attitudes of middle managers and their concerns on how to manage remote workers. Properly introduced, these obstacles can be overcome, making telework-ing a natural modus operandi for many knowledge activities.

The virtual office

Conventional office buildings are often inefficiently used and badly designed for knowledge work. At any one time you may find only 25-30 per cent of individual workspaces actually occupied during normal office hours. The effective utilization rate of this space drops to only 3 per cent if you also take into account non-working hours, holidays etc.11 What other organizational asset is so inefficiently used? More organizations are therefore converting personal space into shared space and using ‘hot-desking’, where individuals do not have their own desk, but use whichever is available when they come into the office. At Proctor & Gamble’s new facility near Cincinnati there are no private offices for senior executives. Work areas are open spaces with rollable filing cabinets, so that team space can be quickly reconfigured.

Furthermore, most offices offer little in the way of diversity needed for different types of knowledge work need. In an analysis done as part of Digital’s flexible work programme, the need for over thirty different work environments was identified, ranging from individual workspace, small rooms for informal meetings, casual meeting space, formal project rooms etc. Yet most office buildings have only a few of these environments, typically individual cubicles and managers’ offices. No wonder that knowledge worker productivity in such offices is low!

Architects and office designers are at last responding to the need for better knowledge working environments. At Proctor & Gamble there are ‘huddle rooms’ where teams can quickly group in a brainstorm and wide corridors with easy chairs that allow people to stop for discussion. Although design helps, the success of the flexible office depends on the motivation and attitudes of those who populate them.

The ultimate flexible office is a totally virtual one. That is what software company Loud-n-Bow achieved in 1995. With many of its professionals working at client sites, the rationale for occupying an office became less clear cut. It took a deliberate decision to close its office and operate entirely using the Internet. As a result facilities costs were slashed by over 80 per cent, and general administration costs significantly reduced.

ROMPing – the creative way to work

The HHCL and Partners advertising agency has a totally flexible office with no enclosed areas. Believing that fixed desks kept employees apart, it initiated ROMP (Radical Office Mobility Programme). There are no personal desks. Employees, including the boss, must find a new office every day. The rompers toolkit is a mobile phone, a portable PC and a personal locker.

HHCL’s meeting rooms have no chairs, so meetings are short and straight to the point. As well as 20-30 per cent more space efficiency, interaction among creative staff is now much higher. The whole area has a buzz about it. People walk about and connect.

With HHCL’s help the BBC who featured ROMPing in its Money Programme encouraged a small experiment in a more traditional firm, the Pearl insurance company. As well as no personal desk, three different rooms were provided.The first is a customer room, based around a kitchen design, to put employees in the mode of thinking customer. The second is a fish-tank room, to inspire creative thinking, and the third the Pit Stop, for fast quick discussion. It is not to be used for more than five minutes at a time. Its design and lack of seating encourage this. Although the employees in the experiment adapted to this, it was felt inappropriate for the whole firm. The main benefit achieved was improved customer service through reduction in end-to-end service time. But this improvement was also attributed to the fact that the pilot group was created from different functions serving the customers. By bringing them together and empowering them as a team, they worked through customer issues until they were resolved, rather than passing them from department to department.

Source: BBC, Money Programme, 8 March 1998, 28 June 1998.

Virtual offices represent a change in perspective from the office as a physical facility to that of the provision of a range of office services. Several suppliers now provide such services, which are particularly attractive for knowledge nomads. The Virtual Office in London will answer the phone in your company’s name and, depending on prearranged instructions, divert the call to mobile or fixed phones, route to voicemail or transfer the message to email.

In conjunction with teleworking the virtual office provides an opportunity to rethink organizational space arrangements. A common misperception is that people need to be close to each other in a physical space to share knowledge effectively. While this is true, studies have shown that in conventional settings personal interaction diminishes significantly when people are further than 10 metres apart. Therefore, other than for casual encounters or for very close teamworking, a teleworker making effective use of technology can be as effective as a person based in an office. In fact, since visits are consciously planned, the quality of knowledge networking is often better.

The virtual corporation

Another type of virtualization is that of the virtual corporation or virtual organization. Many interorganizational arrangements where there is collaboration over time or space can be termed virtual, including joint ventures, or ‘hollow corporations’ that outsource most of their activities. In the knowledge-networking context the most relevant type, especially for smaller firms, is where several organizations pool their complementary resources and knowledge. One such example is Agile Web. This is a network of twenty-one engineering companies in eastern Pennsylvania. It combines skills and resources from the network to meet a wide variety of customer needs, and so bid on business that would be beyond the reach of any individual member. A new virtual organization is created from network members for each customer contract (see also page 232).

In many cases, virtual corporations evolve naturally out of working relationships that have developed between different individuals and companies over many years. While these virtual corporations are in relatively stable networks, others may be created uniquely for a given project. The latter is particularly true for collaborative research in the European Union’s Framework research programmes, whose virtual organizations are also geographically dispersed. Companies and universities from several countries combine expertise by seconding staff, either part-time or full-time, to the collaboration. The project team becomes a virtual organization. European Telework Development (ETD) is such a virtual organization.

Virtual operations

Other forms of virtual organization replace physical activities with virtual ones. Examples are found throughout the whole gamut of business activities, for example in:

ETD – A pan-European virtual teleworking enterprise

ETD is a good example of several principles of virtualization in practice. It is one of over 150 projects supported under the European Commission’s (EC) ACTS (Advanced Communications and Telecommunications Services) programme.12 Like all EC-supported research projects partners must be drawn from different countries of the European Union. Even before its formation participants in the ETD consortium worked virtually over electronic networks.

1 The idea for ETD was first discussed using email between people in the UK, Denmark and Belgium; the two main proposers of the initiative first met through the Internet.

2 The main team was enlisted using similar methods. A core team of people from six countries jointly developed a proposal on-line over several months, before ever meeting face-to-face.

3 Management and co-ordination takes place through a combination of closed email distribution lists, and what is effectively a team intranet operated over the Internet. Team documents are initially developed in WWW format for ease of access, compatibility and sharing.

4 The project uses a media service provided by NEWSDesk,13 itself a company that provides virtual services by delivering press releases electronically.

5 The project embraces a mix of formal documentation, structured databases, bibliographic data and on-line discussion groups. It uses a wide gamut of Internet facilities, including email, the Web,14 list servers and a back-end database engine that generates WWW resource pages on-the-fly.

The project runs as a virtual corporation, with its own ethos, procedures and computer systems (managed remotely from a location in the west of England). Participants come from both large and small organizations, including one-person companies. All are teleworkers, some working exclusively from home, some working only occasionally from home. Much of its work is commissioned directly on-line, often to subcontractors who have not met project partners face to face. Their ability to communicate electronically and perform the work satisfactorily is what defines their suitability, not their geographic location.

• Virtual research. In pharmaceutical research, virtual chemistry has replaced test-tube chemistry as the primary tool in the hunt for new drugs.

• Virtual production. Manufacturing processes are simulated and validated before production lines are built. In Ford’s C3P project, production engineers across several sites manipulate three-dimensional images in a virtual factory to test feasibility of assembly rather than doing physical prototyping.

• Virtual recruitment. Companies are hiring candidates interviewed virtually. Often this is done through videoconferencing. Over half the respondents in an Ernst & Young survey claim to have employed ‘virtual’ candidates.15

• Virtual education and training. There is growing use of distance learning, where course material and tutor advice is given over the Internet. In the Global Executive MBA programme at Duke University, students from different companies and locations also form collaborative virtual teams for project assignments.

The growth of virtualization in all spheres of organizational activity is blurring distinctions between virtual organizations, virtual working and virtual teams.

Virtual teams

Virtual teams are a microcosm of virtual organizations. Like them, they can be virtual in time, space or configuration, or combinations of all three. For example, when Buckman Laboratories wants to solve a technical problem, any of its 1200 employees around the world can contribute. The team may exist only until the problem is solved, perhaps a matter of hours.

Another type is where team members are distributed, such as a team created at NCR to develop their next generation computer system. Over a period of nearly a year, people from San Diego, South Carolina and Illinois worked as a team. When they met virtually they sat around a virtual table, created by a high bandwidth video link which gave the appearance of other people sitting opposite at the same table. This setup was dubbed ‘the worm-hole’. Whirlpool is another company whose on-line systems connect designers around the world. Once highly US focused – in 1987, 96 per cent of its sales were in the USA – it is now a global supplier with 40 per cent of its $8 billion revenues coming from outside the USA. Its vision is to create global designs, getting the best expertise of their employees around the world, while keeping design teams locally based. Previously designers relocated to Michigan headquarters for a period of six months from Whirlpool locations in Brazil, India and Mexico.16

Teams are the nodes in knowledge networks. Like all networks that adapt to changing needs, teams may come and go, change in size, enlist new members, and alter their collaborative links according to the knowledge needed. Virtual teams are dispersed in space, with information and communications technology the glue that allows them to work together. Virtual teamworking at BP provides a good example of how such teaming contributes to improved knowledge flow around the organization.

BP is an organization that has gone through much restructuring in recent years. From over 130 000 employees in the late 1980s, its workforce before its merger with Amoco was 53 000 employees operating as a ‘federation’ of eighty-seven business units across the globe. Information technology has made it possible to replace centralized teams with a more decentralized organizational structure.

One initiative that spawned from BP’s restructuring was virtual teamworking. BP has many virtual teams that are empowered to make decisions, which they do by networking intensively and sharing its knowledge. The technology that makes this possible is multimedia email, document management, Lotus Notes and an intranet. All are seen as essential infrastructure for stimulating knowledge exchange through a global knowledge network.

A key technology that changed the nature of their virtual teamworking is videoconferencing. In 1994, following a proposal by external consultants, BP committed to an eighteenth-month $12 million pilot project. One hundred and fifty desktop virtual team kits that included PCs with videoconferencing and scanners were installed around the world. It allows individuals to communicate with each other more naturally, seeing visual expressions and body language. What was also quickly discovered was that a face-to-face video interaction also generated a higher level of trust between two remote workers.

Virtual teams can be created in an instant. A team at the Andrew oil field in the North Sea oil field can share knowledge with colleagues in the Gulf of Mexico. Furthermore, if there is a problem on a remote site, such as an oil rig, the camera can be trained on a piece of equipment. Thus, though it was once common practice to fly an expert out to the site, many problems can be solved quickly and effectively through a video link.

Knowledge team leader Keith Pearse highlights several ways in which knowledge sharing has improved:

• Speed of completing a knowledge transaction – instead of sending emails to and fro, the shared document facilities allow a dispersed team to complete a joint document in minutes rather than days.

• Making connections that might otherwise be difficult because of travel cost or time considerations. Virtual multiway ‘meetings’ with suppliers have taken place that would otherwise have incurred extensive travel.

• More regular and sustained communications – without the necessity to travel, such interactions can take place more frequently. There is more ‘intimacy’ and understanding in the relationship than would be achieved with email alone.

• Higher levels of commitment. Commitments made ‘face-to-face’ by videoconferencing were more likely to be kept than those made by ordinary email.

A critical success factor in the success of virtual teaming was the use of coaches working with users. In fact, over half the budget for the project was spent, not on technology, but on behavioural and organizational aspects.

Virtual communities

Local communities give people a sense of identity and belonging. Their inhabitants supply each other with local services and support each other socially. A virtual community does the same, except that instead of being rooted in a physical place, it is a locality in cyberspace. It is a community of shared interest. Such communities emerged in the 1980s based around bulletin board systems. Today they exist on the Internet in newgroups, email discussion lists and conferences and on company intranets or groupware systems.

Communities come in many shapes and sizes. Some are open to anyone who cares to join, attracted by the topic of interest. Others are closed, in that they are by invitation or subscription. Some are simply focal points for chat or questions, while others have more specific ambitions. Some allow uninhibited access (which often brings in its wake undesired advertising), while others work through a moderator who vets inputs before posting them for public viewing.

The WELL and beyond

One of the first electronic communities, and still going strong, is the WELL (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link). Rooted in the culture of the San Francisco Bay area, it is an open-ended and self-governing community that started in 1985. Attracting people from a wide diversity of backgrounds, many of them professionals, it hosted computer conferences on a wide range of topics – education, arts, recreations, computers and entertainment. It went on to the Internet in 1992 where over 260 separate conferences are hosted. Its introductory web pages emphasize that it is not just another website or collection of web pages: ‘More than just another “site” or “home page” the WELL has a sense of place that is palpable. Civility balanced by a high degree of expressive freedom has resulted in sometimes startling contrasts in atmosphere from conference to conference. Each conference has a distinctly different sense of place and style, and a loyal group of participants’.17

One spin-off of the WELL was the Global Business Network (GBN), created in 1986, that drew together planners and strategists from companies like ABB, AT&T, Volvo, BP and Bell South. This group used a mix of face-to-face meetings and on-line conferences to develop scenarios of the future. Through GBN, company executives and leading thinkers in a variety of fields would openly share their knowledge and insights. This interplay of knowledge generated new thinking about the future. It also led to increased collaboration between GBN members. For example, Shell and PG&E worked on a joint project to provide compressed natural gas as a fuel.

Whatever your interest, there are places on the Internet where you can meet like-minded people and different ways in which you can do it. Popular with professionals or business people are highly focused discussion lists. There are over 50 000 of these, ranging from ‘Law and Business in Israel’ to ‘The Learning Organization’.18

As well as communities of common interest, there are now business communities focused on a specific set of activities, such as a car or house purchase, or planning a business trip. They are organized by suppliers, trade associations or intermediaries who draw around them complementary suppliers. Such communities are changing the nature of both traditional and on-line markets. For example the conventional recruitment market is dominated by suppliers who advertise for jobs. In contrast the website of Career Mosaic lets job hunters seek suitable opportunities among over 200 participating employers. They can file their CVs on-line and Career Mosaic helps them find matching opportunities. It also provides links to career advice and offers a one-stop shop for job seekers’ needs, including advice on courses and writing CVs. The evolving nature of Internet-based communities, such as Geocities, provides valuable insights for those developing knowledge communities within organizations, a topic covered in Chapter 6.

Community networks

Community networks are another fast developing form of electronic community. They often start from a need for regional and economic development. Typically, they provide on-line facilities in a local community for commercial, educational, social and cultural purposes. Thus, the Manchester HOST started in a disused warehouse to provide on-line services for local community groups (see page 265).

Other community networks are initiated to exploit knowledge. The Tuscany Hi-Tech Network links small and large companies with the local universities of Pisa, Siena and Florence. With a decline of its traditional industries, this region of Italy needed to rethink how its indigenous talent could be better used. The result has been a community that connects research centres, businesses and public institutions. They co-operate as virtual departments in four application areas and seven core competencies, including cultural assets, the environment, biomedicine, robotics and space research. One outcome is a virtual science park that promotes cooperation across the different institutions and diffuses its knowledge around the locality, especially to smaller enterprises.19

Another community that has developed from local origins and now participates in the global networked economy is Taitverkko, a co-operative in Finland.

The Järvenpää Co-operative

Some 35 kilometres north of Helsinki, around 100 inhabitants of Järvenpää have pooled their skills in Ok Taitverkko Järvenpää(the Järvenpää Skillnet Co-operative). It is co-owned by small businesses, freelancers, unemployed professionals and craftspeople, and non-profit community organizations. The skills they offer include environmental consulting, urban planning, legal services, sales and marketing, translation and graphic design. By working virtually on the Internet they attract business from well beyond the confines of their local community.

Lars Tollet, an architect by training, was a founding shareholder of the cooperative in 1993. Local people expressed interest in working close or near to home as teleworkers but also having a neighbourhood office with advanced telecommunications and computer equipment. Tollet has put the experience gained in helping to set up this community to help other similar groups in Finland. As the National Co-ordinator for Finland in the European Telework Development project, he works with other co-ordinators based in eighteen countries across Europe.

Another member of the co-operative is Sonny Nakai, a native of Tokyo. He came to Finland in 1970 and after studying graphic arts at the Helsinki University of Industrial Art, set up his own design studio named IN-Design in 1986. It joined Taitverkko in 1995. He works with international commercial clients producing brochures, annual reports, advertisements, corporate magazines and designing trademarks. Designs are prepared on his Apple Mac computer and sent over the Internet to his clients across five continents.

The co-operative operates as a series of ‘know-how’ teams, which develop and co-ordinate the specialist skills of its members. It maintains a skills register of members and actively networks with other co-operatives in Finland. While not all its members telework, Tollet feels that by operating as a community network and working virtually with clients, they have helped bring work into the locality and have also drawn the community closer together.

Creating the virtual opportunity

The forms of virtualization described in this chapter are evidence of the growing dispersion and mobility of business activity. As ICT infrastructures improve, location independence increases. This creates a double edged sword for individuals, businesses and policy-makers. On the one hand, it lets them access distant resources and markets. On the other hand, this same flexibility means that outsiders can more easily come and compete in their territory.

Table 4.3 Opportunities and threats of virtualization

| Dimension | Knowledge-based opportunities | Implementation issues and threats |

| Location | Creation of knowledge hubs as market attractors in cyberspace knowledge providers Competition from regions with better and lower cost skills Sharing tacit knowledge over a distance | Being attractive to quality Resourcing talent globally Packaging knowledge for remote delivery, e.g. via on-line conferences |

| Time | Capturing knowledge for instant access and reuse later Asynchronous knowledge development around objects Instant access to tacit knowledge through twenty-four hour knowledge networks | Loss of access to knowledge originators over time Changing value of knowledge over time Synchronization interdependencies Balancing supply and demand through time zones and business cycles. |

| Structure | Creating virtual teams or organizations with complementary skills Reconfiguring knowledge flows dynamically according to needs Aggregating knowledge from disparate sources | Developing trust in virtual teams Identifying and rewarding individual contributions Encouraging knowledge sharing across organizational boundaries |

Beyond the obvious strategies of saving costs through tele-substitution and accessing global markets and resources, the best ways of exploiting virtualization come through innovative ways of manipulating its three dimensions. Table 4.3 indicates just some of the possibilities as well as some of the challenges.

Virtualization means that most conventional organizational activities can be restructured in many different ways to take advantage of global knowledge. This calls for a radical rethink of the existing modus operandi by every organization. For many forms of virtualization, it is not the large established organizations that are exploiting these opportunities, but innovative smaller companies, such as Amazon.com, AOL and Geocities.

Points to ponder

1 What current operations or new developments are constrained by access to skills? Could some of these be sourced remotely?

2 Which activities or customer services are suffering from time delays or slowness compared to competitors? Could more advantage be made of ‘sunshine’ operations?

3 Look at your core business processes. How centralized or decentralized are they? Should they be reconfigured?

4 Consider your Internet web presence. How easy is it for potential customers to reach experts? Are you gaining customer knowledge through this channel?

5 Do you have an on-line interactive forum where customers can have a dialogue with your product developers and applications experts?

6 In which electronic business communities do you and other senior professionals in your organization participate? Are you maximizing the use of these as knowledge hubs to create business opportunities?

7 Do you have a formal teleworking programme in your organization?

8 How much does your office space and facilities cost? What is its utilization level? What’s stopping you creating more flexible offices?

9 How effective are the virtual teams in your organization? What stops them from being more effective?

10 Are there customer opportunities that you failed to close, because of lack of necessary resources or skills? Would collaboration with other individuals or organizations have helped?

Notes

1 Pesch, U. (1998). On-line collaboration in the production of Teleworx magazine. Proceedings of On-line Collaboration ‘98, Berlin, June, pp. 57–9. ICEF.

2 Davidow, W. H. and Malone, M. S. (1992). The Virtual Corporation. HarperBusiness.

3 Rheingold, H. (1994). The Virtual Community: Finding Connection in a Computerized World, Minerva Press.

4 A good description of the general impacts of electronic commerce, together with examples, will be found in US Department of Commerce (1998). The Emerging Digital Economy, April. US Department of Commerce. Also at http://www.ecommerce.gov

5 Kinsman, F. (1987).The Telecommuters. John Wiley & Sons.

6 Telecommute America Survey for Smart Valley Inc., Decisive Technology, http://www.svi.org (October 1997).

7 Taylor, J. (1995). The alternative office. Flexible Working Conference, IBC (November) citing Hughes, Sun, AT&T, 3Com and others. See also Financial Times, 8 September 1993.

8 Computing (1995). Adapted from Fears slow down teleworking, 27 April, 46.

9 Michael Wolff, KiNET Associates, Lethen, Scotland (1995).

10 Flexible Working Practices Team (1993). Case Study: The Crescent. Digital Equipment.

11 Lloyd, B. (1990). Office productivity – time for a revolution. Long Range Planning, 23,(1), February, 66–79.

12 European Commission (1996). ACTS Programme Guide, DGXIII-B. European Commission. See also http://www.infowin.org (ACTS Information Window) which has project descriptions of each project.

14 The main website is http://www.eto.org.uk

15 Ernst & Young/HRFocus Survey at http://www.ey.com (April 1998).

16 Hildebrand, C. (1995). Forging a global appliance. CIO Magazine, 1 May 1995.

17 The WELL is at http://www.well.com

18 Several lists and directories of lists exist, e.g. Liszt at http://www.liszt.com lists over 17 000 newsgroups, 50 000 mailing lists and 30 000 IRC channels; or MIT’s ‘List of Lists’ at http://www.tile.com/listserv/index.html

19 Bianchi, G. (1996). Galileo used to live here. Tuscany hi tech: the networks and its poles. R&D Management, 26(3), pp. 199–211.