Chapter 10

Forward to the

future

The future is full of uncertainties. During the course of writing this book, the Asian economic miracle has taken a battering, the whiz kids of Wall Street took a hedge too far, and some commentators are questioning whether the new knowledge economy is really any different from the old. While some of these changes may seem remote to our daily lives, various interdependencies mean that they are ultimately likely to affect us one way or another. Thus, we may find more Western jobs migrate to Asia or we may find it more difficult to borrow money from our bank. So what can we say with certainty about the future of the knowledge agenda?

I spend much of my time analysing developments in technologies and business practice and am regularly asked to make forecasts of their impact. This chapter is no exception. It will give some of my personal projections of how the knowledge agenda will unfold. But this is only one person’s perspective and viewpoint at a particular moment. Therefore the forecasts are prefaced with some general views on how to plan for the future. The book concludes with a review of the challenges facing us, and how we might work collaboratively together to create a future that is prosperous for us all, whatever our desires and values.

Forecasting the future

Forecasting is a huge business. Organizations spend millions of dollars annually with analysts, researchers and consultants for economic and market forecasts. Some of the most expensive are the predictions of sizes and values of different product markets. Research companies are happy to comply, and provide apparently authoritative tables of data neatly presented to two-decimal figure accuracy. When pushed many of them admit that the data is merely an aggregation of what each supplier expects to sell. Some do have more sophisticated models that take into account consumer demand and behaviour, but in the event, and with the advantage of hindsight, many of these forecasts are wildly wrong. Few customers of such data seriously analyse in retrospect the accuracy of what they bought. My own experience is that in boom times forecasters overestimate, and in leaner times underestimate. In other words there is a great human tendency to extrapolate into the future the world as we see it today.

Table 10.1 Examples of two divergent Internet scenarios

| 150 million users (year end 2000) | 500 million users |

| Service providers or key telecommunications services have Y2K problems that disrupt traffic | Digital TVs offer Internet access as a standard feature, so more consumers access it |

| A better method of estimating users is developed, indicating that the 7:1 algorithm (host:users) was wrong all along | Kanji-like editors become affordable so the Chinese and Japanese markets expand rapidly |

| The Internet is replaced by an alternative broadband technology and networks | Internet use is mandated as part of the curriculum in China’s schools |

| Congestion at routers makes it so slow that serious users abandon it | On-line shopping by consumers rises dramatically as retailers go on-line |

| There are battles between interconnection providers, so that the current free exchange of messages at hubs does not take place | Retailers install Internet terminals at sales counters to check on-line catalogues |

| Consumer interest wanes; people find more important things to do with their time | Far East on-line shopping hubs attract many regular shoppers |

| Governments start to impose taxes on data transmission. | Micropayment mechanisms boost electronic markets |

| Internet access is built into household appliances and automatic vending machines | |

Let me give a recent example. An industry analyst forecast in mid-1998 that 327 million people are expected to be accessing the Internet by the end of the year 2000. If you take the estimated number of Internet users in 1995 and project an annual compound growth of 50 per cent (which had been the growth rate in the preceding few years), you would arrive at something pretty close. My two quick calculations using slightly different starting figures came to 300 million and 337 million. What would be more interesting, and gives real insight, is to devise different scenarios as to why it might be only 150 million or as high as 500 million, each of which has rational explanations (Table 10.1).

Thus, the 327 million scenario implies that many of the changes suggested in each column of Table 10.1 do not happen, or that there are counterbalancing factors that boost or dampen demand beyond today’s smooth trend line. This approach of developing alternative scenarios is a technique that Shell has been using for more than two decades. At a time when industry forecasters were projecting an inevitable rise in oil prices, planners at Shell devised a plausible scenario for a significantly reduced oil price. This actually happened with the collapse of consensus among the oil producers in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).1 More important than the scenario prediction was the process of scenario-building, since it forced a dialogue between external experts and Shell managers that gave them greater understanding of the different factors influencing the price of oil. As Dwight D. Eisenhower is said to have remarked: ‘plans are nothing; planning is everything’. In the same vein, despite some problems, Shell today is widely recognized as a good exemplar of the learning organization and is heavily involved in knowledge communities. In contrast, those organizations that take forecasts at face value without exploring the factors and assumptions beneath them are not developing the knowledge they need to use them effectively.

Flexibility

Responsiveness, adaptability and flexibility are characteristics that have been echoed at several places in this book. Having detailed reliable forecasts or intelligence on which to base your plans matters less if you have the flexibility to adapt as the outcomes change. A useful planning grid to help determine your intelligence needs is shown in Figure 10.1. Your overall investment in external intelligence gathering or in buying ever more refined market data depends on the overall level of business impact of a bad forecast and your ability to respond to changes. If, once an external change is detected, it takes too long to respond relative to the impact of the change, then contingency planning and early warning signals are needed to minimize the risk of error. On the other hand if you can respond quickly, then a systematic external monitoring system coupled with effective analysis and good internal knowledge flows may be all that is necessary. Whatever part of the grid you are in, it pays to invest in appropriate knowledge sharing and refining processes, so that the external information is knowledgeably analysed. However, your best investment may be in creating more organizational flexibility, through increased networking and virtualization.

Figure 10.1 Intelligence needs grid

Futurizing

Where do forecasts go wrong? In a classic paper Michel Godet puts it down to people not reacting or behaving as expected: ‘The inadequacy of “classical” forecasting techniques can be exemplified by their downplaying, or outright ignoring, of the role played by creative human actions in determining the future.’2

He then goes on to say that there are multiple possible futures, and that the resulting outcome is shaped by human action. In ‘la prospective’ approach, the future is actively created and not forecast. By using scenarios as a tool to create alternative futures, people and organizations can determine which ones they want to help bring about through the involvement of the influential actors.

It is this perspective that Skandia has adopted in an approach it calls ‘futurizing’. Its innovations are not only shaping its own future but are influencing the whole insurance industry and beyond. In May 1996 the first Skandia Future Centre (SFC) was opened at Vaxholm on the Stockholm archipelago: ‘And despite its location on the periphery -geographically speaking - in terms of the global flow of ideas it is right in the centre. Through SFC - eventually also in other locations in the world - Skandia aims to advance its position in the market and innovatively create its future instead of being surprised by it.’3

Futurizing involves bringing together futures teams, that comprise individuals drawn from different groups in Skandia and who represent the 3Gs (three generation age groups of twenties, thirties and forty-plus), different competencies and geographic perspectives. They view the future as ‘an ocean of unexploited opportunity’ and think creatively of how Skandia might innovate in it. They also involve external ‘competence partners’ in this innovation process which starts, not from Skandia’s existing products, but from a perspective of different future worlds and the life stages of its customers. A visitor to the centre enters through a door that resembles the bow of a ship. Inside is a layout designed for thinking and knowledge exchange. Furniture is comfortable, room layout is flexible, and there are high-tech facilities to record the structured dialogue that is steered by experienced facilitators. All help to create an informal yet purposeful atmosphere where participants are committed to creating the future. The challenge I pose to all readers of this book is, how can we collaboratively futurize a prosperous future enhanced by knowledge?

Scenario development

A technique that can play a useful role in futurizing is that of scenario planning. Typically it involves a number of iterative phases such as the following:

1 Analysis of trends and anticipation of potential discontinuities in the wider environment – economic, political, regulatory, technology, social and demographic, environmental. A discontinuity is something dramatic, such as a major earthquake in California or a collapse in financial markets.

2 Determining the inter-relationship between different variables. This depends on the relative strength and direction of different drivers and inhibitors, and the actions of key influencers. Techniques such as cross-impact analysis can be used to identify clusters of reinforcing trends.

3 Development of alternative scenarios that combine different sets of trends and discontinuities. Mostly these will result in a point of divergence along a trend line, e.g. oil prices continue to increase vs a collapse in oil prices.

4 Creation of event strings. These are pathways through time with the occurrence of events that cause the scenarios to unfold.

5 Drawing together the different strands into a cohesive story. Story-telling is a powerful method of conveying and discussing scenarios. They can either describe a future state or how we go from here to there.

Although scenarios are backed up by hard data and forecasts, their richness comes from the creative thinking of participants and constructive dialogue. In the Open University’s MBA course on the external environment, students develop scenarios in groups, using on-line computer conferencing as a tool. Over the years some very instructive scenarios of the wider global business environment have been devel-oped.4 Let us now consider some trends in the knowledge movement and what scenarios might result.

Knowledge futures

Many developments in knowledge management have been driven by technological advances. However, its current relevance in most organizations is largely due to the way that good knowledge management can contribute to topical business issues, such as the need for efficiency and the drive for improved products and services. It is part of many important management activities – managing information (explicit/recorded knowledge), managing processes (embedded knowledge), managing people (tacit knowledge), managing innovation (knowledge conversion), managing assets (intellectual capital). Each can benefit by more explicit consideration of the knowledge dimension. Its pivotal role is leading to a convergence of different developments that are in turn leading to some discernible trends.

Ten trends in knowledge management

1 From a dimension of other disciplines to a recognized discipline in its own right. Since knowledge offers a unifying perspective over many different management disciplines we can expect to see knowledge management emerge as a subject in its own right. Already modules are being developed in degree and MBA courses and professors of knowledge Management are being appointed.

2 From strategic initiative to routine practice. The CKOs of the future (if they exist) will embrace some of the functions of today’s human resource managers and chief information officers. Not only will there be specialist knowledge roles, such as knowledge editors or knowledge brokers, every professional and manager will need some essential knowledge skills to be proficient in their job.

3 From an inward focus on knowledge sharing to an external focus on creating value. As organizations gain efficiency through better sharing of best practice and other knowledge, their focus will shift to creating value. They will better understand the contribution of knowledge to business performance and apply and repackage it in creative ways for customer benefit. They will spawn entirely new lines of businesses based predominantly on knowledge. For example, a manufacturer of engineered products might create an engineering consultancy business.

4 From best practices to breakthrough practices. Sharing best practice gives incremental improvements in performance, usually of the order of 10-30 per cent per year. Copying what others are doing is a prescription for mediocrity. True market leadership comes through innovating with breakthrough practices that achieve improvements of tenfold or more in key areas, such as time to market, and functionality per unit cost. This is what every organization should strive for, as such achievements are not uncommon.

5 From knowledge processes to knowledge objects. Computer applications are moving to object orientation, where the focus is on entities and how their state is changed, rather than on procedures. Expect more packaging of knowledge as objects that might include a chunk of information record, a multimedia clip and personal contact hyperlinks. Knowledge objects can be combined, manipulated and transmitted in different ways. Markets will be created where knowledge objects can be bought and sold (such as in project Alba described on page 279).

6 From intellectual capital to tradable knowledge assets. Many companies will start to identify and measure their intellectual capital – in databases, in human competencies, trademarks etc. Once identified these then become opportunities for packaging and resale, perhaps several times over. For example, publishers have sold their mailing lists for many years, but many other companies are now realizing the opportunities from trading their databases, e.g. fleet car managers and car reliability information.

7 From knowledge centres to knowledge hubs and networks. Although aggregating knowledge and knowledgeable people at knowledge centres gives critical mass, a more effective model may well be local nodes of expertise interconnected through human and computer networks, i.e. the virtual knowledge centre.

8 From knowledge maps to knowledge navigators/agents. Maps are static representations of objects, and without extensive real-time map-making capability (which could happen in the future) we need other ways to find existing and emerging knowledge. These will be human brokers (people with know-where and know-who), navigation aids on websites and increasingly intelligent software agents that dynamically seek out changing and new knowledge.

9 From knowledge communities to knowledge markets. Knowledge communities provide an effective vehicle for knowledge exchange. But as knowledge acquires value, and becomes ‘productized’ as objects (Trend 5) these communities will develop payment mechanisms and other trappings of a marketplace. The phrase ‘a penny for your thoughts’ may assume real meaning as people have microchips embedded under their skin which handle knowledge transfer and micropayments under directives from the human brain!

10 From knowledge management to knowledge innovation. Knowledge management as a transition phase to something more fundamental. Management implies custodianship and managing what you know -innovation is creating something new and better, and that surely must be the ambition of all of us.

Source: I3 UPDATE (No. 20), June 1998 at

http://www.skyrme.com/updates/u20.htm

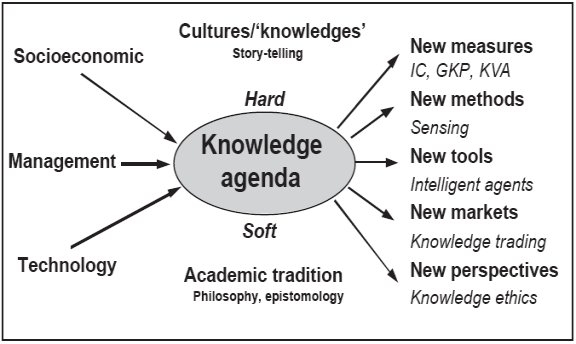

These specific trends are just one perspective of what is happening in the wider knowledge agenda. As noted in Chapter 1, today’s knowledge agenda emerges from several evolving megatrends. It is the result of a confluence of developments in the socioeconomic environment, management thinking and technology (Figure 10.2).

As practised in organizations, knowledge management is, as has been demonstrated in Part C of this book, a blend of hard and soft factors such as ICT insfrastructures and organizational culture. Recently apparent among leading practitioners are more sense of cultural aspects, the traditions of oral story-telling and the influence of academic thinking. Current best practice in knowledge management is daily becoming more widely known, through conferences, books, articles and the sharing of knowledge by successful practitioners. However, if collectively we are to develop better futures through knowledge, what should now be the focus of our thinking and experimentation? What should we plan to embed into future practice? I suggest the following five themes:

Figure 10.2 The evolving knowledge agenda

• New measures. As is happening at the enterprise level in Skandia and at country level through the work of organizations like the OECD, the WEF and the IMD, non-financial measures that will guide us to the future need to be developed. Intellectual capital measures are a start, but we need other measures such as KVA (knowledge value-added) and GKP (gross knowledge product).

• New methods. Many enterprises have quickly recognized that knowledge initiatives are not simply making information accessible on an intranet, but also involve changes in human behaviour and culture. New methods and practices are needed in almost every aspect of office work – running meetings using structured dialogue, developing better ways of sensing significance in a sea of data.

• New tools. Chapter 3 highlighted many technological solutions that enlarge the scope of knowledge from individuals to the organization as a whole, such as document management, computer conferencing and knowledge management suites. New tools that will work more intuitively and symbiotically with humans to enhance individual knowledge and understanding include intelligent agents, visualization and mapping tools.

• New markets. New electronic markets will evolve as places to exchange and commercially trade domain-specific knowledge. They will provide for trading of explicit knowledge (information) as well as giving access to communities and individual experts.

• New perspectives. The pivotal role of knowledge in all aspects of society, not just in business, means that individuals and organizations will need to take a much wider perspective of the environment in which knowledge is used. A key strand that is likely to emerge is that of knowledge ethics, raising issues over the ownership and governance of knowledge, and how important knowledge can be made widely available for the public good.

Several of these themes have already been covered in earlier chapters. Knowledge markets and knowledge ethics merit more attention here.

Knowledge markets

The selling of explicit knowledge on-line in the form of information is not new. But developments on the Internet will increase the variety and scope significantly. With micropayment mechanisms, it will be possible for people to find and pay for relatively small amounts of information or knowledge, costing perhaps only a few cents, on a pay-as-you-go basis. It will also be possible to sell virtual consultancy, on-line advice by the minute or per problem solved, and run collaborative knowledge events. Precursors of such markets are those of Knowledgeshop, iqport and ideaMarket.5 These have knowledge stores where content creators have deposited information and other knowledge products, and details of online events. Knowledge providers receive royalty payments of up to 50 per cent as items are bought.

However, even these are rudimentary compared with what is possible. Imagine a networked consultancy like TelTech (page 55) operating entirely on the Internet with connections being made in real time and pricing taking place dynamically according to supply and demand. Developing a vision along these lines is Bright: ‘the network for smarter networking’.6 Primarily focusing on the domain of leading edge management knowledge, its key elements are:

• an accreditation process by which information assets are reviewed by experts, graded and priced with consent from the provider;

• a content ‘wrapper’ that provides information about the content of the knowledge asset; this is classified and indexed according to a knowledge thesaurus; the content might simply be the credentials and contact details for an expert consultant (a piece of know-who);

• a technology platform (iqport) for secure trading that allows pay-per-view and micropayments, and provides billing services that enable content providers, the platform provider, intermediaries, accreditors and others to receive a percentage of the revenues;

• dynamic pricing according to supply and demand;

• web conferencing tools for virtual collaboration, running communities and on-line events.

Such a development is indicative of the trend to package knowledge objects for resale. Another example is that of trading designs in the semiconductor industry (see panel opposite).

Knowledge ethics and governance

Ethical considerations are growing in importance in many organizations. They recognize their role in being part of an inclusive society in which the profit motive is not the be all and end all. They have to meet the aspiration of a broad group of stakeholders and trade in a manner consistent with the values of the communities within which they operate. Ethical considerations also arise in knowledge management. How far should an organization exploit an individual’s prior or private knowledge for its own benefit? What rights does an employee have to share in the rewards of such knowledge? A frequently cited reason against knowledge sharing is the concerns of some individuals that the organization want to pump them for all they are worth and then dispense with their services.

Alba – an example of intellectual property trading

The semiconductor industry is a good example of the trade in intellectual property. The next generation of computers will be based on systems on a chip. These combine functions that conventionally are on different chips and linked on a circuit board. Development times and costs are reduced by reusing subcomponents from different chips and mixing and matching them in new ways. The design and marketing of subcomponents, which are in effect blocks of intellectual property (IP), has become an industry in itself. A collaborative initiative between Scottish Enterprise, Cadence Design Systems, IBM and other organizations, project Alba provides an electronic network that provides a market place for these virtual components. Intellectual property blocks are traded and new designs can be validated to check that they do not infringe existing IP.

Such issues, though, pale into insignificance when the ownership of knowledge for the public good is concerned. How much should knowledge that can widely benefit the human race be kept as proprietary knowledge that is tightly controlled by an owner trying to maximize their commercial interests? Nowhere more stark is this debate than in the field of biotechnology and genetic engineering. Pharmaceutical companies are hunting down ancient tribal remedies based on the knowledge of the medicinal properties of plants, with a view to patenting them. Patents are also being sought for naturally occurring genes. Commenting on this emerging field of bio-prospecting, Tim McGirk writing in Time asks: ‘Should a government, company or scientist have the right to claim ownership to the innermost workings of a living organism?’7

Proponents argue that finding the right genetic material is like finding a needle in a haystack and this effort should be justly rewarded, e.g. through patent protection. Others question what benefits will be shared with a tribe like the Onge tribe of the Indian Ocean whose herbal brew may hold the key to a cure for malaria.

Another example that has caused much heated debate is that of so-called terminator technology, where genetic engineering produces seeds that produce only one crop. The offspring seeds do not germinate, so farmers have to buy new seeds from the supplier each year. The terminator patent is jointly owned by Delta & Pine Land (D&PL), a subsidiary of Monsanto, and the US Department of Agriculture, since the technology development was jointly developed with support from public research funds. When D&PL sought exclusive licensing rights, there was an outcry against such commercial exploitation of what opponents called an ‘immoral technology’ and the need to protect ‘the fundamental right of farmers to save seed and breed crops’, especially poor farmers in rural economies.8 The organization orchestrating a worldwide protest, Winnipeg-based Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI), commits itself to ‘the sustainable improvement of bio-diversity and the socially responsible development of technologies useful to rural societies’. The recent developments in patenting genetic knowledge have raised its concerns about the impact of intellectual property rights on world food security.

There are other issues of knowledge governance that raise their heads owing to technological advances. How should knowledge markets, as discussed above, be regulated? What controls are needed to tame ‘wild agents’ – autonomous intelligent agents with undesirable characteristics that either through poor design or malice roam networks causing havoc with legitimate trading? IBM research has already shown that agents who trade with each other, left to their own devices, are likely to create wild fluctuations in market prices.

An existing knowledge market, financial futures, gives a foretaste of the challenges that lie ahead. Finance is a key resource in today’s economy. Yet it has moved well beyond its initial role of a medium of exchange or a key factor of production (one of the trio: land, labour and capital). Money is a tradable commodity. For years there have been markets in stocks and shares, bonds, foreign exchange. Now there are markets in financial futures and a whole host of other ingeniously devised financial derivatives. These products are the result of knowledge innovation, the creative application of knowledge. These markets, as noted earlier, are only peripherally connected to other markets such as that in goods and services. In the UK, for example, the daily trade in derivatives is half of the country’s annual GDP. What value does such trading bring to furthering a true knowledge society where desirable outcomes are successful businesses of all sorts and quality of life for citizens?

Traders in financial derivatives leverage large amounts of finance from small investments. Market values fluctuate significantly and fortunes are made and lost almost in microseconds. Economics Nobel prize-winners provided the fundamental ideas behind derivatives trading at Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM). But more established financial institutions had to bail it out as its financial position became untenable. In the regular stock market, intervention has been needed to halt computer trading when price swings get too violent. Will knowledge markets evolve in the same way, needing bodies to govern them, analogous to the Securities and Exchange Commission?

Knowledge scenarios

Consideration of the trends and issues described earlier leads to several possible scenarios of how the networked knowledge economy might develop:

• Money rules OK. The knowledge economy never materializes to any great degree. The emergence of third world countries into newly industrialized nations and people’s innate desire for material goods sustains value in traditional goods and services. Scarcity in key materials, the power of financial institutions and large conglomerates, and nations at war, all restrict investment in knowledge industries and help reinforce traditional vehicles of wealth.

• Knowledge rich vs knowledge poor. A divided world with knowledge haves and knowledge have nots. Traditional economies coexist with the new. Within developed countries society is divided between the educated rich who have global connections, access to knowledge and latest technology and those who simply survive at subsistence level. Imbalances in regulation lead to a reinforcing cycle of continued investment in knowledge rich countries. Today, for example, Pfizer refuses to invest in India because of its weak IPR regime.

• Techno-dependency. The world becomes over-reliant on technology, which increasingly lets us down in unexpected ways. First, there are relatively minor disruptions in telecommunications traffic and a small percentage of companies go out of business because of the millennium bug. Later, weak points in the Internet give way causing more disruption. A foretaste of this occurred in August 1997, when human errors caused failures of significant portions of the Internet. This is compounded by intelligent agents playing havoc in previously stable enterprise computer systems. Intellectual energy is diverted simply to restoring stability in systems and reverting to the relatively stable computing environment of the late 1990s.

• Knowledge idealists vs knowledge imperialists. Two types of community emerge based on different value sets. One recognizes the commercial value of knowledge and believes that it should be traded as any other economic commodity. The other believes in knowledge as a public good. It pitches big corporations with financial power against individuals or collectives, as in the clashes already noted in the field of genetic patenting. The idealists create self-contained enclaves or knowledge kibbutzim networked globally into an alternative economy.

• A collaborative sustainable knowledge economy. All nations and individuals with different value-sets harmonize their differences to address common global problems and coexist peacefully. Concerted intelligence is directed to addressing both the economic problems of the third world and the environmental problems of the developed world. There is high investment in lifelong education and knowledge-intensive activities around the world. There is universal access to basic information and knowledge, yet mechanisms to give knowledge creators and exploiters due rewards. There is more equality of opportunity and less imbalance between rich and poor, yet meaningful incentives for individuals to achieve more than average prosperity. Everybody achieves personal fulfilment.

At the time of writing, any of these seems a potential alternative. As the future unfolds and our understanding of the knowledge economy improves, other plausible futures may become apparent. Equally there may be scenarios that combine elements found in each of the ones above. For example, some groups or even countries may exclude themselves from the third scenario and become the knowledge-rich of the second. Although my personal preference is for the last scenario, this is will only happen if there is a collective will to make it happen, combined with commitment and access to knowledge and other resources.

Knowledge networks for knowledge

As the interest in knowledge grows, there is a corresponding growth in the number of networks and communities that are collaboratively exploring the developments and addressing the implications. The Knowledge Ecology Network (KEN), mentioned in Chapter 6, has over 300 members organized into small groups that are developing guidelines, creating knowledge architectures and looking at the needs of knowledge professionals. Created by George Pór and colleagues at Co-I-L (Community Intelligence Laboratories) it uses web conferencing (Caucus) to gel a network of knowledge professionals from around the world to further the ideal of ‘unleashing the capacity of knowledge professional to self-organize into a global network of mutually supportive relationships’. It plans various knowledge products and services that will help both individuals and organizations gain value through knowledge. Other networks and individuals are thinking along similar lines -of elevating knowledge networking from a narrow organisational perspective to a broader base socioeconomic force that can change the world.

Kenniscentrum CIBIT in Holland, is host for the International Knowledge Network. It is aimed more squarely at promoting good knowledge management practice within organizations. It runs events, carries out regular studies and runs a discussion forum. In fact there are a growing number of websites, such as Karl Erik Sveiby’s (http://www.sveiby.com.au) that offer much useful information and opportunities for discussion (see Postscript A).

Another organization is the Washington-based Knowledge Management Consortium (KMC).9 A society of knowledge managers, practitioners, and scientists, it brings together individuals and organizations ‘to develop a shared vision, common understanding, and aligned action about knowledge and knowledge management’. It has groups working on standards and is developing a certification programme for knowledge managers and knowledge management engineers, professionals, technologists and instructors. It now has chapters in several countries.

As knowledge management grows in importance, we can expect to see many more such organizations and networks vying for the attention of professionals. Like other knowledge networks, teams will gel around key issues and agenda items. The networks and teams will interconnect through boundary spanning individuals, and their activities will overlap and co-ordinate in different ways. There is one network, however, that has a vision that goes farther than any of these. It has a programme that to my mind epitomizes the essence of the networked knowledge economy, and will drive us towards the future of our final scenario – the sustainable networked knowledge economy. The network is the ENTOVATION Network of Global Knowledge Leaders and the programme is the development of the Global Knowledge Innovation Infrastructure (GKII).

Global Knowledge Innovation Infrastructure

The ENTOVATION Network is a network of over 3000 individuals in fifty-five countries around the world who have come into contact with the work of Debra Amidon and her vision of the knowledge innovation.10 One of its unique features is that it transcends every business function, industry and region of the world. All have a contribution to make towards the collaborative enterprise of tomorrow. Core members from around the world were surveyed for the Global Knowledge Leadership Map (http://www.entovation.com/kleadmap/). Results were premiered at the Twentieth Annual McMaster Business Conference (20 January 1999) in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, in a presentation ‘Tour de Knowledge Monde.’

Representatives from over thirty countries responded with their reflections and aspirations. Their responses reflected many different perspectives but displayed some common threads. First, the transformation to the knowledge economy is more a function of behaviour and culture change than technology. Second, these changes are difficult, but well worth the effort. Amidon summarizes:

Clearly, knowledge is seen as the engine for value-creation. What lies in the future is/must be grounded in values, competencies and the quality of relationships. It is an economy of open access rather than knowledge being perceived and managed as a ‘private good.’ The reasons are because of the bountiful nature of the resource and its quality to multiply as it is shared with others.

This new economy we are innovating works for the people creating a world free of poverty, disease and violence. It is an economy directed toward sustainable development placing knowledge at the point of need or opportunity. It is an economy that is transnational in scope – balancing the local/national needs with a global scope. The driving mandate is one of creating a society with a better quality of life and increased standard of living worldwide. And the initiative begins with the individual – where knowledge resides!11

How can this collective vision be built? Amidon argues the need for a specially built global infrastructure for knowledge and innovation. This is the premise behind the GKII, an idea first described in Chapter 10 of her book, The Ken Awakening. She envisages bringing together both practitioners and theorists into a community of knowledge practice – a ‘world trade of ideas’ – that reconciles the technological, behavioural and economic issues of participants from around the world.

The GKII will provide a vehicle to leverage the different competencies in ways that support local and global efforts simultaneously. In knowledge management work we have seen how good generic knowledge principles developed in one area, such as the US Army’s ‘After Action Review’ can be successfully transferred into other enterprises, as at BP Amoco. The main focus of the GKII is therefore to provide forums for structured dialogue around the knowledge innovation. It will have a research agenda based on practical experimentation, host a world congress and launch knowledge innovation awards. The GKII was formally launched at the Banff Management Centre in Alberta, Canada, in November 1998. Banff’s spectacular setting provides a great stimulus for creative thinking and inspiration while the not-for-profit Banff Centre provides a unique blend of three kinds of knowledge – the Centre for Management, the Centre for Cultural and Performing Arts and the Centre for the Environment. Geographically it is a bridge between East and West.

The GKII is perhaps the ultimate exemplar of a knowledge network to build the collaborative enterprise. Globally dispersed participants will bring their knowledge to bear on key problems and issues in the form of a global learning ‘collaboratory’ (a contraction of collaboration laboratory). Prototypes will be developed of new knowledge. Ideas will be converted into action, either new processes or perhaps collaboratively created new products and business opportunities. The agenda will stimulate collaboration across the different boundaries – of function, industry and geography.

The future is what we make of it

Many readers of this book will be in organizations that have embraced knowledge management as a worthwhile management practice. They may even be successfully exploiting some of the strategy levers described in Chapter 2! But as this final chapter suggests, there is still much to do before the benefits of knowledge are fully realized. There is scepticism among a fair number of senior executives I meet, who feel that knowledge management is indeed a passing fad.

It is instructive to look at how some other one-time ‘fads’ have evolved. Few large companies today do not practice total quality management, at least in some form. Quality has become embedded in all their products and processes even though you will frequently find companies who are not practising what they preach. Similarly, most organizations have introduced some form of business process re-engineering, even if not as radical as Hammer and Champy envisaged.12 Both concepts, unlike a passing fad, have matured into a set of desirable management practices, that in turn have stimulated a thriving industry for experts, suppliers of tools and techniques, training and other services. Because of its fundamental importance, there is every likelihood that knowledge management will do the same if properly applied.

For me, the exciting possibilities that surround the exploitation of knowledge are not just in commercial organizations. They are in enterprises of all types that serve society as a whole. And by enterprise, I mean any purposeful initiative. As we look around the world today and see all the problems and opportunities that exist, yet at the same time a wealth of human talent, it surely does not take rocket science to think of the tremendous possibilities for creating better and more fulfilling futures for everyone on the planet? No, what it takes is purposeful knowledge networking of human intellect, globally, and augmented as never before by knowledge technologies. That is fundamental to building the collaborative enterprise. I hope that the perspectives given in this book will help you in that quest.

Notes

1 Schwartz, P. (1991). The Art of the Long View: Scenario Planning – Protecting your Company against an Uncertain World. Doubleday.

2 Godet, M. (1982). From forecasting to ‘la prospective’: a new way of looking at futures. Journal of Forecasting, 1, pp.295.

3 Skandia AFS (1996). The future as an asset. In Power of Innovation: Intellectual Capital Supplement, Skandia AFS interim report, p. 8.

4 Mercer, D. (1998). Future Revolutions. Orion. The methods are described in Mercer, D. (1995). Scenarios made easy. Long Range Planning, 28(4), 81-6.

5 http://www.ideamarket.com, http://www.knowledgeshop.com and http://www.iqport.com

6 http://www.bright-future.com

7 McGirk, T. (1998). Dealing in DNA. Time, 30 November, pp. 60.

8 Rural Advancement Foundation International (1998). Say no to terminator. http://www.rafi.org/usda.html

9 Knowledge Management Consortium (KMC) at http://km.org.

10 Amidon, D. M. (1997). Innovation Strategy for the Knowledge Economy: The Ken Awakening. Butterworth-Heinemann.

11 Global Knowledge Leadership Map. I3 UPDATE, Special Edition at http://www.entovation.com (January 1999). The map itself is at http://www.entovation.com/kleadmap/

12 Hammer, M. and Champy, J. (1994). Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution. HarperBusiness.