Chapter 3

Technology: the

knowledge

enhancer

The notion that computers can enhance knowledge processes is not new. Even before modern computers were invented, scientists such as Alan Turing described how they might exhibit human thinking qualities. In the 1970s and 1980s, experts predicted that artificial intelligence (AI) systems would be prevalent throughout business, even taking over from humans most routine decision-making activities. The concept behind one type of AI system, the expert system, is deceptively simple. First, elicit knowledge from a human expert, codify it, and store it in a computer knowledge base. Then provide an interface for less knowledgeable people to dialogue with this knowledge base so that they can act like an expert. This sounds like a dream solution to a principal challenge in knowledge management, that of making individual expertise widely accessible to the organization as a whole. Unfortunately, things are not that simple. Today our views have shifted from this emphasis on ‘thinking machines’ to one of using machines to help humans thinking.

The different ways in which they can do so are demonstrated in this chapter which starts by positioning different knowledge technologies. There are examples of a wide variety of software tools that include text mining, conceptual mapping and intelligent agents. However, it is collaborative technologies, a category that includes groupware, intranets, videoconferencing and document management, that have delivered the most widespread benefits to knowledge practices. Opportunities of using technology to further the knowledge agenda are vast. The main challenges are not technological but are the related human and organizational factors, a theme that is further developed in the toolkits of Chapters 5 to 8.

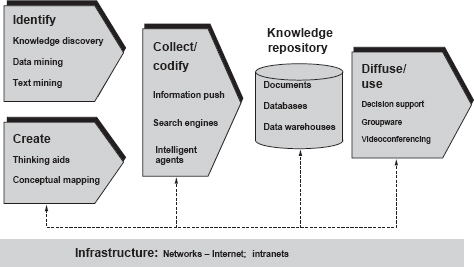

Figure 3.1 Knowledge technologies in their wider applications context

Knowledge tools

Most established applications of information and communications technologies involve automating routine procedures. They represent the codification and logical structuring of knowledge as depicted in the knowledge cycles of Figure 2.6. Their inherent knowledge is well known and expressed explicitly. However, this represents only one segment (A) of the broader field of technology applications (Figure 3.1).

Better opportunities for applying ICT in pursuit of the knowledge agenda come from the other three quadrants of the figure:

• Segment B. In these applications, technology is used to give better access to information, and to provide better ways of manipulating and interpreting it. Specific tools include text search engines and visualization software.

• Segment C. Tacit knowledge held by experts is accessed through collaborative technologies such as groupware and intranets. Communications infrastructures create rapid pathways to these known sources of expertise.

• Segment D. The individual and group processes by which knowledge is generated and developed are enhanced through tools such as group decision support systems (GDSS), modelling and computer conferencing.

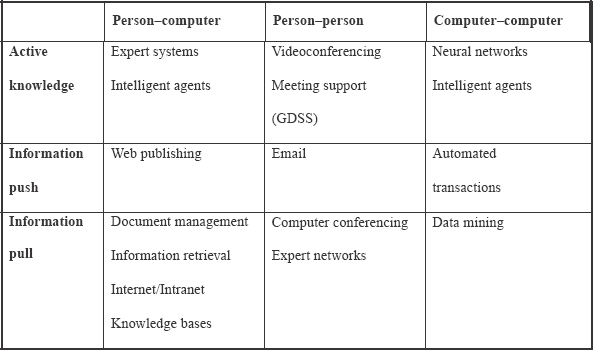

Another perspective on how technology can enhance knowledge is gained from a systems viewpoint that considers the conversion of knowledge inputs into outputs (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Examples of ICT support from a knowledge systems perspective

| How ICT can enhance | Examples of tools | |

| 1 Knowledge inputs (information supply) | Scans more sources Filters according to profiles Condenses information User-oriented presentation Extracts hidden information | Intelligent agents Email filters Relevance ranked searches Concept retrieval Visual maps Data and text mining |

| 2 Knowledge processing | Retrieves case histories Rules and induction More rapid combinations | Case-based Reasoning (CBR) Expert systems |

| 3 Knowledge repository | Reduced cost of storage Holds most current information Single point of reference | Thesaurus management |

| 4 Knowledge flows | Timely routing Improves workflow Alerts users of changes | Email and distribution lists Workflow software ‘Push’ technology Intelligent agents |

| 5 Knowledge outputs (use/creation) | Supports thinking processes Informs decision-making | Cognitive support tools e.g. conceptual mapping, idea generation Decision support tools; meeting support; business modelling and simulation |

A related perspective is that of a knowledge value chain (Figure 3.2), which also indicates a selection of supporting tools. This is a simplified schematic since there is usually not a one-to-one relationship between tools and processes. Some tools, like conceptual mapping, can be used to identify existing knowledge and gain insights, as well as creating new knowledge.

Whichever framework you use to position knowledge tools, the range of technology is large and constantly evolving as suppliers increase their investment.1 This means that any named tools referred to in this chapter are likely to be quickly superseded by new developments. Nevertheless there are some common underlying categories and technologies that we shall focus on. Surveys of knowledge tools find the following as those most widely used: email, intranet, Internet, data warehouses, decision support, groupware, videoconferencing, on-line information access and document management. Among this list data warehousing and decision support are felt to be less effective than the others.2 The following sections reviews representative tools from the broad perspective of their ability to leverage value through knowledge. We start by considering the hubs around which knowledge activities revolve - knowledge repositories.

Figure 3.2 Technology in the knowledge value chain

Knowledge repositories

The hub of an organization’s explicit knowledge is one or more knowledge repositories. With the cost of electronic storage declining rapidly, it becomes practical for organizations to store larger quantities of their critical information and make it widely available through their corporate networks. Electronic knowledge repositories exist in many forms (Table 3.2). It must be remembered, however, that the best organizational knowledge repository is in the minds of its people. This helps explain why collaborative technologies are seen as the most effective knowledge enhancers.

Data warehouses

A data warehouse integrates information from multiple sources into a consistent format and makes it more amenable to analysis. For example, British Gas integrated data from twelve separate regional systems into a single warehouse containing information on all its 22 million customers. Data warehouses give knowledge workers access to large volumes of information that can be analysed in many different ways. This helps in decision-making, especially for marketing decisions such as store location and layout, and customer targeting.

Table 3.2 Examples of knowledge repositories

| Repository | Typical information and use |

| The Internet | Comprehensive resources across many scientific and business disciplines. Uses include scientific and market research |

| External databases | Marketing and competitive information, general business news. Used to inform marketing and product development decisions |

| Document databases | Manuals, drawings, customer correspondence. Used in customer service to bring up all information related to specific customer |

| Data warehouse | Financial transactions, point-of-sale data. Used to discern trading patterns for target marketing, location of stores etc. |

When used with knowledge discovery tools, such as data mining, users can identify correlations, patterns and trends not previously discernible. For example, Sequent captures service engineering data, and looks for patterns and trends in performance and reliability that are then fed back into the product development process.

Document management

Document databases are another common repository for knowledge. Documents give the user more context, structure and visual impact than when the same information is reduced to standardized computer-based text. Therefore, many document management systems, such as those from Dataware and Documentum, are geared to give knowledge workers easier access to original documents, as well as adding contextual information, such as the rationale for a document, its revision status and applicability. Another feature that helps sharing of interpretative knowledge is that of ‘redlining’. This allows users to add comments directly to documents, and these then become part of the document base and organizational memory.

Organization-wide document management plays an important role in helping the sharing of the most up-to-date knowledge in many applications, such as clinical trials in the pharmaceutical industry and large-scale complex projects. Construction company John Brown3 introduced document management for the rapid sharing of information between its engineers, who are located around the world. Drawings can be retrieved and viewed on a computer screen within seconds, compared to several days in the former manual system.

On-line databases

Knowledge-intensive enterprises have a thirst for external information. Common sources are on-line databases, available through providers like Dialog and the Internet. Once these were quite distinct. On-line services used proprietary software, had heavily controlled content and bundled together access and content as an integrated service. In contrast the Internet is open to anyone and much information is free. Now the two are converging with on-line providers offering Internet access, and many reputable sources also available directly on the Internet. What is often not appreciated is the sheer volume of material held by on-line service providers. At the end of 1997 Dialog had around fifty times more content than all of the World Wide Web.

Knowledge workers traditionally accessed on-line services through an intermediary, such as a librarian. Today, more services are delivered directly to the knowledge worker’s desktop computer. However, information intermediaries add value often not duly recognized. They filter, edit and refine incoming information, and know how to track down and assess sources. A survey done by the knowledge centre at American Management Systems also found that, on average, a trained information specialist could find relevant information eight times faster than the consultants they served.

Knowledge creation

There are several types of tool that assist thinking and creativity, either individually or in groups. One type is exemplified by IdeaFisherTM, one of the longest established idea generation tools. It has a word repository and templates for different creative activities, such as developing a new product or choosing a brand name. New ideas are stimulated by applying well-known creativity techniques such as word association or word triggers.

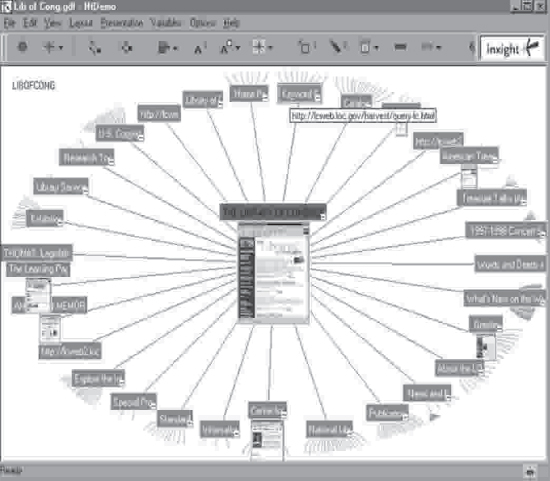

Another category is that of concept or mind mapping. Users manipulate ideas by grouping them together or randomly linking them to create new ideas. Mind maps have been popularized by Tony Buzan, and a tool like The MindManagerTM draws heavily on his methods. Figure 3.3 shows a mind map of this chapter. Users can drill down trees, annotate entries with notes or documents, link to other maps and create hypertext output. Another tool, Idons-for-ThinkingTM, uses hexagons which are colour coded according to the nature of the concept, e.g. green for a new idea, blue for a strategy and red for an action. Other tools, such as Decision Explorer, focus on the causal relationships between concepts. You can specify, for example, that faster innovation needs better knowledge management, which in turn needs effective tools. Computer analysis quickly identifies core concepts and uncovers circular arguments.

Figure 3.3 A mind map of this chapter

In the field of invention various tools guide developers through brain-storming, selecting options and validation. Invention Machine draws on a core repertoire of ninety-five inventive principles, such as colour change or segmentation, collated from over 2.5 million patents. It steers inventors to ideas from other fields and highlights design contradictions.

Usage of creative tools within business is generally quite low. Many creative individuals feel that technology gets in the way of their thinking processes. However, as the tools become easier to use, they do provide a way of recording ideas and sharing mental models that can later be retrieved in new but similar situations.

Knowledge discovery

These tools help to identify new patterns and knowledge in large volumes of data. The simplest knowledge discovery tools are query tools that work on structured information. On Line Analytical Processing (OLAP) is one such class of tool often used with a data warehouse. It allows queries such as ‘how many units of product X did we sell to customer Y in region Z during a given time period’. Marketers at Glaxo Wellcome use OLAP to query a database that contains a decade of historic information on sales of over 2500 products. They can analyse sales trends through different outlets, such as hospitals and pharmacies, and gain a better knowledge of customer and market dynamics.4

Data mining

Unlike query tools, data mining uncovers associations and patterns without the user having to know in advance what questions to ask. Various artificial intelligence techniques are used. Genetic algorithms, such as those used in IntelligenceWare’s IXL, apply biological principles of genetic mutation to continually refine their effectiveness. Routines that do not work well are discarded, while those that work better are combined with others to continuously improve the algorithm. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are another set of techniques that to some extent mimic the behaviour of neurons in the human brain. A network of processing elements is trained on known data and then let loose to discover new relationships in other data. In marketing, Sun Alliance started using neural networks as early as 1992 to improve the targeting of its mailshots.

Knowledge unearthed by data mining is often unexpected. One frequently cited example is that of a large US supermarket chain that discovered a strong association between purchases of a brand of babies’ nappies and a brand of beer. No normal hypothesis or data query tool would have discovered such an association, but data mining revealed its existence.

Data mining is particularly good at identifying sequences, associations and clusters. Whereas humans have difficulty in dealing with more than a handful of variables, data mining tools can cope with thousands at a time and discover new knowledge that would elude most humans.

Text mining

One solution to the growing problem of information overload is that of text mining. Like data mining it identifies relationships in vast amounts of data. Concept Agent from New Age Paradigms uses the natural language techniques of syntax parsing, lexical attributes and linguistic rules are used to draw out key concepts from large documents.5 The output is a short summary, which may include the most relevant whole sentences from the original document. Research using a similar system at BT Martlesham Laboratories has shown that summaries can be abridged to 25 per cent of their original length, while still retaining virtually all of the information in the author’s abstract. Even a reduction to 5 per cent of the original retains 70 per cent of the information.6

A new generation of text analysis tools, such as SemioMap, provides visual concept maps from the multiple sources of text that it analyses and mines. Users can navigate their way through these maps, uncovering connections between apparently unrelated concepts and seeing how a corpus of documentation is evolving. This is one example of how visualization will play an increasingly important role in knowledge work.

Visualization

Presenting information in visual form is an increasingly common way of humans and computers working symbiotically in a wide range of knowledge work. Statistical packages, such as SPSS, use these techniques to identify market segments from large amounts of multidimensional market research data. Users can view three-dimensional images that through colour coding of individual data elements reveal groupings representing distinct clusters of customer need.

NETMAP is one of a growing class of tools that shows connections between different elements of information. A common application is identifying the communications patterns in an organization that are usually quite different from those you would expect from an organization chart. Another example is that of a citation tree in Smartpatent’s patent analysis system. It shows relationships between patents, R&D activity and technological competence according to citations in various documents. Different colours can be used to show competitor activity around key technologies. Inxight’s Hyperbolic TreeTM developed at Xerox offers what is termed fishbowl or hyperbolic tree views of information (Figure 3.4). A concept of interest is placed centrally on the screen, that shows links to other concepts, with the strongest and nearest links close to the centre, while more remote ones are shown in less detail. The viewer can drag on one of these to bring it into closer detail.

Three-dimensional visualization is used extensively in simulations, allowing humans to add their tacit knowledge to the explicit information presented. In the oil industry geologists and engineers visualize the geological make up of oil reservoirs and use the derived knowledge to make decisions on where and how best to drill.

Information gathering

These tools play a key role in making knowledge workers more productive by giving them rapid access to the information they need, when they need it.

Search engines

Internet users are well acquainted with search engines such as AltaVista and Yahoo! that retrieve information stored across many repositories. Users most common complaint is that too many matching hits are returned. A partial solution is to use keywords combined in Boolean expressions such as ‘FIND knowledge AND management’.

More advanced search tools use artificial intelligence techniques and can accept natural language queries such as ‘the role of knowledge management in customer retention’. The resultant documents are then ranked according to their relevance as calculated by various techniques, such as word frequency. Muscat, for example, complements Boolean and statistical retrieval with probabilistic retrieval, where variable weightings are assigned to every word in its database. It monitors users’ interactions, and weights according to the relevance users attach to different documents. Related approaches are concept retrieval that distinguishes which concept is behind the use of a word with multiple meanings, and fuzzy logic retrieval that looks for patterns of similar though not exactly identical words. Such approaches are also being applied to the classification and retrieval of images and moving videos, as in Excalibur’s RetrievalWareTM software.

Figure 3.4 A visualization tool (Hyperbolic TreeTM). Source: Inxight Inc. (reproduced with permission)

Searches themselves can yield additional knowledge. At Schlumberger a modified search engine allows researchers to see who else has made similar queries and shows comments recorded by previous searchers about their line of enquiry.7

Intelligent agents

Intelligent agents are a class of software that operate autonomously and semi-intelligently, some might even say knowledgeably. There are two main categories - passive and active. Passive agents filter and monitor incoming information streams, sorting out highly relevant material. Active agents leave their host systems and actively roam around networks, seeking out information of interest to its owner. They can then generate alerts. These are messages that prompt the user when new information is available.

Knowledge UpdateTM from Autonomy is an example of an active agent that acts like a personal assistant to its owner. Users create one or more agents to search the Internet and bring back relevant information. The agents are trained to perform better by rating the relevance of the items they retrieve. Unilever uses agents to keep individuals abreast of developments in their specialist fields. Associated software identifies users with similar interests, informs them and so helps them form a knowledge community.

Customized information provision

There are a growing number of services that deliver information directly to users’ computers via email or the World Wide Web. Examples include Desktop Data’s NewsEDGE, Dow Jones’s Interactive and Reuters’s Business Briefing. Typically they source material from several thousand trade periodicals, the daily press and news agencies.

An important development is that of customization. Information is tailored to the different needs of individual knowledge workers, according to their interest profiles. They then receive the top stories that most closely match their profile. For example, the customized news service First! selects about twenty stories for each user from its daily input of 17 000 news stories from 650 sources. It uses the artificial intelligence techniques just described to refine profiles and alert users of breaking news.

Push vs pull

Searching on-line databases and the Internet are examples of ‘pull’ technology. You access information when you need it. This also has the advantage that the information is current and may also have been well structured by a specialist database provider. In contrast, email and customized information services are examples of ‘push’ technology -information is pushed from source to user. With many people now receiving more than 100 emails a day, push is difficult to cope with. One approach is to throw even more technology at the problems that other technologies have inflicted! Electronic ‘filters’ apply rules to the headers and contents of messages and automatically route them to different files, including the waste bin.

A different form of push is that provided by companies like Pointcast or BackWeb. Information, according to a user’s profile or requested sources, is downloaded on to their personal computer in background mode over the Internet or an intranet. They can then browse this information at their convenience. Despite the hype from suppliers, push strategies are what librarians have been doing for years. They call it selective dissemination! Today’s technologies merely make it easier to automate.

Most knowledge workers will use an appropriate balance of push and pull. They will pull information from repositories as needed. As well as allowing retrieval through search engines, a well run repository will have information organized in a consistent structure, with suitable navigation aids such as visual knowledge trees. Knowledge workers will also allow information to be pushed at them, but by using agents, filters and personal profiles they will have the opportunity to be more selective in what they accept.

Knowledge development

Once users have access to information, there are various ways in which they can use it and process it to refine and develop knowledge. Three types of tool are now outlined as examples of the more structured processing at the right-hand side of the codification funnel of Figure 2.3.

Simulation and modelling

Computer models and simulations allow a knowledge team to share mental models and surface hidden assumptions. One class of tools is that of systems dynamics, popularized in the example of the ‘beer game’, an inventory management system described in The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook.8 It illustrates how the best decisions are often counterintuitive to normal management thinking. Eric Wolstenholme, director of Cognitus, runs simulation workshops for managers in several industries. He describes computer based simulation as: ‘virtual worlds which put a manager in control of an organization he can “fly”. Just as in an aircraft simulator, he is presented with challenges and opportunities, and will probably “crash” the organization frequently to start with! The simulator provides feedback and guidance until the key principles and lessons are learned, and the organization “flies” successfully’.9

Simulation is particularly useful at identifying interdependencies. BP Exploration uses modelling to understand the interdependencies between key factors in North Sea oil fields - the reservoir, production platforms, operational and capital costs and commercial management. Although staff previously had access to many detailed models, such as reservoir simulation and financial spreadsheets, it was business modelling that helped the management team gain a ‘big picture’ overview and test ‘rule of thumb’ assumptions.10

Guidance systems

These are a specific type of decision support system, typically using expert systems, that guide users through a decision-making or problem-solving process. Despite their earlier shortcomings, expert systems are now making steady inroads into those areas of business where decisions need access to best available knowledge. Common uses are in medical diagnosis, insurance underwriting, systems fault-finding and problem-solving at customer call centres.

A typical example is that of credit scoring for loans. Previously such an application would have a simple procedural algorithm. Now it relies on inductive reasoning and rules held in a knowledge base. Michael Wolf of Swiss Bank Corporation describes how such a system has been linked to another technique described earlier – data mining. Data mining was used to identify patterns in the characteristics of loan defaulters from a large database of loan history. This was then compared with the suggested outcomes generated by the current guidance system. This approach gave insights into rules and induction processes needed to enhance the current system.

Case-based reasoning

The basis behind this technique is a knowledge base of cases, especially of problems and solutions. When a new situation arises, ‘fuzzy logic’ is used to match it to past cases. When cases with similar characteristics are found in the knowledge base, the solutions can be reused or adapted. In turn the current case description and its solution become part of the evolving knowledge base. The European awareness project CASTING (Case-Based Reasoning Stimulation of Industrial Usage)11 portrays case-based reasoning as a four-stage cycle:12

• Retrieve the most similar cases from the knowledge base.

• Reuse the knowledge from those cases to solve the current problem.

• Revise and adapt the proposed solution.

• Retain the experience for the future.

The helpdesk at NatWest’s BankLine (a desktop banking service for corporate customers), uses case-based reasoning to guide operators through a dialogue to solve customer problems (see Note 12).

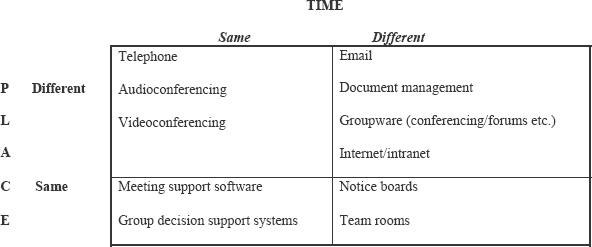

Collaborative technologies

Of all technologies, it is collaborative technologies, such as the Internet, that are making the most impact on knowledge networking. Collaborative technologies enhance person to person collaboration and the sharing of organizational information and knowledge. Almost any software that allows shared access over a network can be considered a collaborative technology. However, the significant ones are more generic and universal, and are depicted on a space-time grid (Figure 3.5).13 Examples from each quadrant will be considered starting with same-time same-place technology.

Group decision support systems

Personal computer presentations projected on to large screens are a feature of many meetings. The screen becomes a medium for sharing personal knowledge with a larger group. A limitation is that at a given time, only one person is controlling the output. In contrast, group decision support systems, such as GroupSystemsV and VisionQuest, are designed for group interaction and simultaneous input. Typical functions in such systems are:

Figure 3.5 Positioning of various collaborative technologies

• Brainstorming – users enter their thoughts which are added to a shared list.

• Categorization and grouping – a facilitator groups and reorders the ideas.

• Voting and preferences – participants weight or prioritize ideas, from which average rankings are generated, or they can vote on a proposal, anonymously if preferred.

• Issue exploration – commentary is added and topic relationships determined; in some systems relations are depicted visually as concept maps.

Such systems can make meetings more productive than conventional ones. Decisions are reached faster, often in less than half the time. The involvement of every participant helps to achieve greater consensus and ownership of the outcome. The assumptions behind decisions are recorded and become part of the organization’s knowledge base.

Although these systems continue to grow in popularity, they are still far from being widely accepted in many organizations. Their success depends critically on user acceptance and expert facilitation.

Information persistence

Technology supporting the bottom right quadrant of Figure 3.5 is usually ‘low tech’. The note left on somebody’s desk, the department notice board, and the shift log book are examples. The information they contain remains in one place over a period of time. In knowledge management there is growing recognition of the importance of such information persistence. By keeping key information permanently visible, recall and idea stimulation is higher. Many organizations are developing this notion by devoting team rooms for projects. Charts and whiteboards act as a vehicle for knowledge development, such that team members dropping in get a sense of a project’s current status and issues, and can add their own updates.

Steelcase is one company that has taken information visibility and persistence a step further. In its new executive suite, the walls are lined with large-screen flat displays which allow senior managers to see important information whenever they are there. Some information is relatively static, but since the panels are updated in real time, managers can view the latest sales and business statistics.

Videoconferencing

The same-time different-place quadrant contains technologies that aid simultaneous communications over a distance. Telephones are univer sally used but videoconferencing is rapidly becoming an essential tool for knowledge networking.

It is commonly reckoned that effective communications relies roughly 10 per cent on words, 20 per cent on voice and tone, and 70 per cent on ‘body language’. Videoconferencing adds in this important visual element to conversations. It creates as near a face-to-face experience as is possible over a distance. Videoconferencing systems come in many forms. Some are camera and monitor systems used in rooms to link together two or more groups. A recent development is low-cost desktop conferencing that uses a standard personal computer with a small camera mounted on the monitor. Callers can see each other in image windows, and at the same time share application windows. Hence they can converse at the same time as jointly manipulating a document or spreadsheet.

For example, design teams at Ford based in the UK, US and Germany work together as part of a ‘virtual global design centre’. They talk through designs while using shared electronic whiteboards. Videoconferencing played a significant role in reducing car design cycles from three years to two. A good example of the use of videoconferencing for knowledge networking is BP’s virtual teamworking project (see page 113).

Groupware

Groupware is a technology that transcends space and time. The term was invented by Doug Engelbart at the Stanford Research Institute in the 1960s as the use of computers for ‘the augmentation of human intellect’. Its focus was to help knowledge workers share their expertise, particularly in a distributed environment. Engelbart’s prototype hypertext system that later became Augment had email, computer conferencing and shared-screen editing. Computer conferencing allows users to go to online topic files or a bulletin board and add their own notes to a thread of conversation.

Today there are over 300 groupware products, of which Lotus Notes and First Class are among the best known. There are also a growing range of World Wide Web conferencing tools such as Caucus and O’Reilly’s WebBoard. Compuserve’s forums and AOL’s communities provide similar facilities in on-line services. Groupware has several features that enhance knowledge networking:

• Multiple data types are handled – free form text, graphs, images, voice and video.

• They combine both email and ‘bulletin board’ functions.

• Messages are displayed as threads of conversation, so it is easy to distinguish original postings and replies.

• Users can switch between different views, for example to see records relating to authors, customers or topics.

• Conferences or discussion lists can be public or private, allow entries to be posted directly or via a moderator (who checks for suitability).

• Most have a web interface; Domino, the latest version of Lotus Notes allows files to be published in WWW format and can take web pages as part of a Notes database.

Groupware features widely in many organizations’ knowledge programmes. For example, Thomas Miller and Co., a manager of mutual insurance companies, found that Lotus Notes significantly improved knowledge sharing among its employees and agents around the world. Its databases aggregated formal information, about geographic regions, the types of risk managed and customers, alongside emails and informal discussion. This helped its member companies make better risk decisions, develop proposals faster and get closer to their clients.

Intranets and the Internet

In the last few years the proportion of large companies that have installed an intranet has risen from less than 10 per cent to over 70 per cent. They are an important part of the infrastructure of many knowledge initiatives, offering several benefits for knowledge networking:

• Easy-to-access and use. The use of WWW browsers gives a familiar and easy-to-use interface to information and applications.

• Universal access to information. Information can be kept on any ‘server’ on the network, and can be accessed from anywhere within the intranet.

• Rapid publishing of information. Individuals can easily publish information pages from their word processors.

• Person-to-person interaction. Intranets simplify interaction between people in different locations through email and computer conferencing.

• Scaleable networks. As organizations restructure, it is easy to add or remove servers to the overall network.

• Access to external information and knowledge. Intranets usually have gateways to the external Internet, which give access to a rapidly growing global information resource.

In addition, implementation is relatively low cost compared with other groupware solutions, because of the wide availability and low cost of most Internet software. Intranets link people to information and people to people. For information, an intranet can simultaneously be a formal electronic library and an informal publishing medium. For person-to-person interaction, an intranet provides a place for making personal connections, communicating and community building. By themselves, intranets do not create or share knowledge. The key to a successful intranet implementation is good content, a well designed information architecture and good information management.

Many companies use an intranet to stimulate organizational knowledge flows. Perhaps the world’s largest is AT&T’s, whose 80 000 users can access thousands of different areas of information. It also has conferencing facilities that allow knowledge communities to evolve and work effectively. At Hewlett-Packard, an intranet is core to its corporate strategy.

Intranet boosts knowledge sharing at Hewlett-Packard

The Hewlett-Packard (HP) intranet has more than 2500 computers that act as web servers. It transmits more than 1.5 million electronic mail messages daily. Lew Platt, HP’s Chief Executive describes its contribution:’HP’s corporate culture has always encouraged open communications among employees. With the advent of the corporate Intranet, information sharing has taken off like never before’.

Platt comments that HP was using an intranet in 1989, long before the name was invented. He views it as offering tremendous opportunities for HP to increase its intellectual capital by sharing and leveraging knowledge.

One use of the intranet is in product management, where design teams, manufacturing and product management teams all share the same information. This has resulted in better forecasting, improved scheduling of products and faster time to market. Hewlett-Packard’s intranet has over 100 internal newsgroups. Topics discussed in these ‘virtual conversations’ cover everything from computer architecture to problem tracking. Another application is Electronic Sales Partner, which gives sales representatives access to over 10 000 up-to-date documents. It is also used as an extranet, in which customers can access selected information directly and communicate with HP personnel.

Perhaps the most important benefit of HP’s intranet is that it encourages increased collaboration. It enables people to work more co-operatively across organizational boundaries.

Sources: Hewlett-Packard’s website (http://www.hp.com); Platt, L. (l995).The corporate intranet: a new model for conducting business, real people doing real business, Business Week’s Futures Executive Conference, San Francisco, (December l995).

The Internet extends the reach of an organization’s intranet to the outside world. Even though more facilities might be available, response times are generally slower, and the information may not be as well managed or reviewed as that internally. Nevertheless it is widely used to expand an organization’s access to information and knowledge.

With the wide range of collaborative technologies available, it is easy to dismiss email as an old-fashioned and unsophisticated technology. But this is not so. It is still the most heavily used application on the Internet. In many companies it has already taken over from the telephone as the primary means of business communications. Its functionality has increased significantly in recent years. You can attach documents, images and voice messages. You can send a message to a distribution list that delivers to every participant in a knowledge network. You can manage files and folders, and have them indexed by a search engine for efficient retrieval. Let us not forget that more information sharing and knowledge development probably takes place through email than any of the other technologies or tools mentioned in this chapter.

Five roles of collaborative technology

Collaborative technologies fulfil five overlapping roles in knowledge development:

1 A knowledge connector – they connect people to information and people to people. The Internet provides many starting points to find appropriate information or expertise.

2 A tool for improved communications – constraints of geography and time are overcome. Conversations are recorded as organizational memory.

3 Access to information repositories – from a single computer users can access terabytes of dispersed information. Furthermore much of that information is more comprehensive and up to date than if individuals manages it themselves.

4 A vehicle for active knowledge exchange – conferencing facilities, both synchronous and asynchronous, allow workers to share knowledge and collaborate in its ongoing development.

5 An alternative to conventional meetings – meeting support systems capture additional knowledge in face-to-face settings. Groupware lets participants contribute to virtual meeting at times and places of their choosing.

Collaborative technologies must be appropriately chosen and used. Asynchronous electronic communications cannot replace sensitive face to-face negotiations. Neither groupware nor videoconferencing can wholly replace a highly interactive meeting that engages people emotionally. As a general rule, collaborative technologies come into their own where a wide variety of perspectives and knowledge is needed and participants are geographically dispersed. Many implementations of groupware and videoconferencing have not met expectations. This is due to insufficient attention to human and social factors during implementation. In BP’s virtual teamworking project, the largest proportion of spending was not on technology but on addressing these factors.

Integration and suites

Since collaborative technologies form a central plank of knowledge management initiatives, many suppliers of these technologies are combining several functions into one software package. One example is the extension of groupware into the same time dimension. Ubique’s CoWorker, for example, is an add-on to Lotus Notes that lets like-minded people connect in a real-time conversation. Just as today we see office suites such as Microsoft Office or Lotus SmartSuite that integrate what were previously separate tools, we can expect similar moves with knowledge tools. Thus, Dataware has extended its document management system into a full knowledge management suite that associates documents with experts, whose details are held in a directory of expertise. Open Text’s Livelink integrates document management with intranets, and adds user commentary and conferencing facilities.

The technology opportunity

The wide range of tools described in this chapter show that there is hardly any aspect of knowledge work where technology cannot lend support. Individuals and organizations should continually think about how they work with knowledge and where technology can have the most impact.

Collaborative knowledge work

Knowledge work involves a wide range of activities, including accessing information, classifying and organizing it, thinking, and communicating with others. An organization that is thinking strategically about using technology to enhance its knowledge capabilities should therefore have a broad spread of technologies that help knowledge development (Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6 A knowledge development framework

The following are some examples of how knowledge technologies have been exploited in a range of collaborative applications:

• Scientific research. Scientists can more easily keep abreast of their colleagues’ work and offer informal critiques. Glaxo Wellcome’s intranet with desktop videoconferencing helps its research groups share research results and discuss DNA sequence diagrams. This makes knowledge networking more effective and helps lead to drug breakthroughs.l4

• Sharing best practice. Rover Group’s GLEN (Global Learning Electronic Network) gives each shopfloor operator access to best practice in manufacturing and production, with specific case examples from other parts of the group.

• Collaborative design. Teams from different organizations and locations bring different perspectives to create innovative products. It is easier to solicit inputs from users about proposed features.

• Faster and better problem-solving. Price Waterhouse’s KnowledgeViewSM gives their business consultants access to best practice. Its unique thesaurus allows comparison of business processes across a range of industries. This helps them deliver better customer solutions much quicker than when the knowledge was dispersed and fragmented.

• Faster project proposals. ICL’s Café Vik knowledge repository holds proposal templates and project knowledge that can quickly be assembled to create customer proposals. It allows salespeople to assemble more finely tuned proposals quickly and economically.

• Improved customer services. All a company’s expertise can be accessible from the front line. Buckman Laboratories gives every employee a portable computer that lets them tap into the company’s knowledge network K’NetixTM wherever they are. This gives them access to information resources, discussion forums and email. This helps them comes up quickly with the best solutions to customer problems.

These applications illustrate the value of making information readily accessible. Knowledge, previously dispersed, can be quickly aggregated and applied. Additionally, communications pathways provide access to experts, who supplement information with context-specific advice.

Information technology knowledge levers

Another way to think about opportunities is to consider each of the strategy levers described in Chapter 2 and consider how technology can enhance them (Table 3.3).

The human challenge

Several challenges need to be addressed if the application of knowledge technologies is to be successful. The first is the perceived problem of information overload, itself a consequence of technology proliferation. While information customization and intelligent agents offer some relief, a clearly thought out personal information strategy, as discussed in Chapter 5, is probably the best antidote.

A second challenge is to recognize that many of the tools described deal only with explicit knowledge or information. Yet the best knowledge in an organization is tacit knowledge in people’s heads. Therefore, most technology needs complementing with non-technical processes and methods that help tacit knowledge transfer.

The largest challenge is that which has for years afflicted implementation of ICT systems in general. It is inadequate attention to human and organizational factors. This challenge is accentuated with knowledge management systems since knowledge networking is a very people focused activity. The introduction of technology needs to be sensitive to the needs and working patterns of those whom it is intended to help.

Table 3.3 ICT and knowledge levers

| Knowledge lever | Typical ICT levers | Example |

| Customer knowledge | Data mining to extract buying patterns Customer dialogue on focus discussion lists Registration and feedback forms on websites | Microsoft software developers monitor discussions on relevant Internet newsgroups, even though they are public forums and not managed by Microsoft |

| Products and services | Internet websites for latest product information and updates On-line enquiry points for customer service | Federal Express allows customers to track the progress of their package through the Internet |

| Knowledge in people | Knowledge elicitation in expert systems On-line discussion lists or forums that give access to expertise Expert directories on intranets | Medinet gives users access to medical expertise through the Internet. They ask questions of a doctor |

| Organizational memory | Intranets and groupware holding project histories Document management systems giving access to product information | Hoechst Celanese’s idea bank holds ideas and results of research, available for use at any time in the future |

| Knowledge in processes | Workflow software that codifies best process practice Current procedures and forms on an intranet | Sales representatives at Cadence Design Systems use an intranet-based systems that guides them through a sales process supported by a one-stop sales support encyclopaedia |

| Knowledge in relationships | Extranets that give customers access to internal experts Special forums for specific account teams and customers | Relationship managers at Chase Manhattan can access customer knowledge held on multiple legacy systems |

| Knowledge assets | Asset management systems Executive Information Systems | Engineering company S.A. Armstrong use a pbViews executive information system to monitor key measures of intellectual capital |

Even greater dangers lurk ahead if we unwittingly put too much reliance on technology without understanding the consequences. The millennium bug has been a timely ‘wake up’ call. In the near future we are likely to see more information and knowledge exchange over computer networks taking place between intelligent agents. If we abdicate too much responsibility to them, we could be in for another rude awakening. A sobering thought is that artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence by about 2015. How will we cope then?

Summary

This chapter has demonstrated how a wide range of technologies can enhance knowledge activities. Of all those discussed it is collaborative technologies, such as groupware and intranets, that have the greatest knowledge leverage and organizational impact. They connect people and allow them to collaborate in ways hitherto not possible. They provide conduits for knowledge flows and give universal access to information, wherever it happens to be.

Knowledge technologies directly affect the way that people work, either individually or with others. Since styles of knowledge work are very personal, organization-wide implementation of knowledge technologies is likely to pose even greater difficulties than implementation of other ICT systems. Achieving success requires attention to organizational and human factors, aspects that feature prominently in the toolkits described in Part C of this book.

The opportunities afforded by knowledge technologies are limited only by human ingenuity. In particular, some of the best opportunities come from exploiting the dimensions of time and space in creating effective virtual environments, the topic of the next chapter.

Points to ponder

1 Has your organization successfully deployed artificial intelligence applications? If so, what did you learn about the kinds of problem they were most suited to?

2 What techniques (e.g. data mining, on-line conferences) do you use to discover new knowledge about your customers?

3 Where do you most frequently need quick access to tacit knowledge where videoconferencing might be a help?

4 Do you have knowledge bases where you can quickly find a) solutions to customer problems? b) product ideas that were shelved, but may be useful in future? c) your best expert on doing business in China?

5 Do you know where to find key corporate policy documents? Are authorship, validity and ownership clear? Are there contact details to ask more detailed questions?

6 Can everybody in your organization easily communicate and send documents to each other via email?

7 Can you do the same with your key suppliers and customers in a confidential way?

8 How reliable and accessible is your organization’s IT infrastructure (access to critical applications, email, intranet) - as reliable and consistent as the telephone? What about when you are on a business trip abroad?

9 On your intranet or groupware system, can users find the information they require within three mouse clicks of the home page?

10 What is your track record of success with new IT systems? Are applications using the technologies described in this chapter being initiated by the IT department or business users?

Notes

1 An analysis done by Trend Monitor International in 1997 identified thirty-three main categories (http://www.skyrme.com/updates/u16.htm). Its knowledge tools monitoring service continues to refine and develop knowledge tool schemas (http://www.trendmon.demon.co.uk).

2 Sources include ‘20 questions on Knowledge’, a survey by Ernst & Young/Business Intelligence, summarized in Chapter 2 of Skyrme, D. J. and Amidon, D. M. (1997) Creating the Knowledge-based Business: Key Lessons from an International Study of Best Practice, Business Intelligences; Chase, R. (1997). The knowledge-based organization: an international survey. Journal of Knowledge Management, 1(1), September, 38^9; Murray, P. and Myers, A. (1997). The Facts about Knowledge. Cranfield School of Management, The Cranfield/Information Strategy Knowledge Survey, cited in Information Strategy, September 1997.

3 (1996). Engineers create a global office. DEC Computing, 10 April, 13; also application note at http://www.documentum.com/jbrown.htm

4 Chang, P. and Ferguson, N. (1996). The data warehousing boom. Conspectus, February, 2–3.

5 New Age Paradigms at http://www.nipltd.com

6 Natural Language Group, BT Laboratories, Martelsham. See information at http://www.labs.bt.com/

7 Merline, K. (1998). Schlumberger creates cutting-edge KM network. Knowledge Inc., 3(3), March, 1–5.

8 Senge, P. M., Roberts, C., Ross, R. B., Smith, B. J. and Kleiner, A. (1994). The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization. Nicholas Brealey.

9 Eric Wolstenhome, Cognitus Limited, Harrogate, England, 1997.

10 Application note1, Cognitus Limited, Harrogate, England, 1997.

11 CASTING: Case-based reasoning. Project web pages at http://www.ace.co.uk/casting/overview.htm

12 Dempsey, M. (1996). Phone service transformed. Financial Times, FT-IT, 6 November.

13 Johanson, R. (ed.) (1991). Leading Business Teams. Addison-Wesley.

14 Additional source material – Silicon Graphics application note1 at http://www.sgi.com