The Counter-Influence of Emerging Markets across the Globe

Overview

The emerging markets have been the source of global economic growth for quite some time now, with far-reaching effects to the rest of the world, in particular to advanced economies. It is not news that emerging markets have become the sweethearts of the financial press and a favorite talking point of governments, foreign trade advisors, and corporations worldwide. Although these markets were best known in the past as a commodity paradise, or the place to go for natural resources, cheap labor, or low manufacturing costs, emerging markets today are positioned for growth. Rapid population development, growing middle-class, and sustained economic development are making many international investors and corporations look to emerging markets with new lenses.

Economic theorists’ corroborate this point by arguing that free FDI across national borders is beneficial to all countries, as it leads to an efficient allocation of resources that raises productivity and economic growth everywhere. Although in principle this is often the case, at this time, for emerging markets, the situation is a bit different. It is much more apparent now when we look at country indicators from sources such as the IMF or World Bank, that large capital inflows can create substantial challenges for policymakers in those market economies. After the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, net private capital flows to emerging markets surged and have been volatile since then. This raises a number of concerns in those recipient economies. As advanced economies issued robust monetary stimuli to revive their sluggish economies, emerging markets faced an overabundance of foreign investments amid strong recoveries. Hence, policy tensions rapidly ensued between these two groups of economies. As strong FDI, mainly private net capital, was injected into emerging markets economies, both in pre- and post-global financial crisis periods, policymakers in those emerging economies reacted by actually reversing the flow of capital back into advanced market economies. This often resulted in an effort to control local currency appreciation, and fend off the exporting of inflation from advanced economies into these markets.

Therefore, we are all witnessing a rapid development in the global trade landscape, one that hitherto was dominated by advanced economies, with trading policies developed typically by members of the G-7 group of nations. Some members of the G-7 group though are beginning to lose their influence to emerging economies, as a result of profound changes the global markets are undergoing. One of the most important changes, henceforth the consequences of which still remain to be understood fully, is the growing role of the G-20 countries as new policymakers for international trade and fast developing emerging markets.

These groups of emerging economies, however, are not easy to define. While the World Bank coined the term emerging countries more than a quarter of a century ago, it only started to become a household term in the mid-1990s.1 After the debt crises of the 1980s, several of these rapidly developing economies gained access to international financial markets, while at the same time they had liberalized their financial systems, at least far enough to enable foreign investors broad access into their markets.1 From a small group of nations in East Asia, these groups of emerging economies have gradually grown to include several countries in Latin America, Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle East, as well as a few countries in Africa. The leading groups today are the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), the BRICS, the CIVETS, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), in addition to what Jim O’Neil calls the N-11, or next-11 emerging economies, a focus of much discussion in this book.

When studying emerging markets today, it is important to understand how the global economy is changing, what the world will look like tomorrow, five years from now, a decade from now, and how it will impact each of us. The weight of the emerging markets is already significant and being felt throughout the advanced economies and it is likely to expand further. The implications of the rise of the emerging markets on the world economy, some of which is already evident and will be discussed later in this chapter, cannot be disregarded by governance of the global economy organizations.

The Influence of Emerging Markets across the Globe

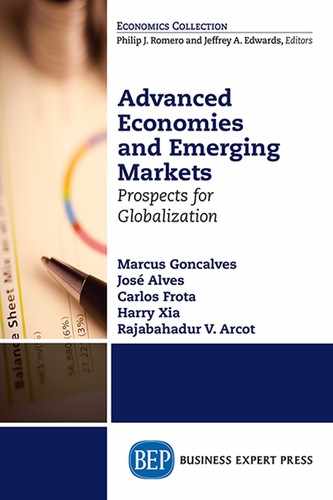

The impact and influence of emerging markets on advanced economies and global trade is impressive. Today, these countries constitute over half of the world’s population, with China and India accounting for over one third of it. As a result of intense economic transformations many of these emerging economies are facing rapid urbanization and industrialization. As of 2013 nine of the ten largest metropolitan areas in the world are located in emerging markets. (See Figure 2.1.)

By 2050, the world’s population is expected to grow by 2.3 billion people, reaching about 9.1 billion. By then most of the world’s new middle class will be living in the emerging economies of the world, and most of them in cities. Many of these cities have not yet been built, unless you count the plethora of ghost cities in China; cities built with the entire necessary infrastructure. Physical infrastructure, such as water supply, sanitation, and electricity systems, and soft infrastructure, such as recruitment agencies and intermediaries to deal with customer credit checks, will need to be built or upgraded to cope with the growing urban middle class.

Figure 2.1 Top 10 largest cities in the world, 2013

Source: IMF World Outlook, 2013

As far as purchasing power, by 2030 the combined purchasing power of the global middle classes is estimated to more than double to $59 trillion. Most impressive, over 80 percent of this demand will come from Asia alone. That will come at a price though, as it will require an estimated $7.9 trillion in investments by 2020. Meeting these needs will likely entail public-private partnerships, new approaches to equity funding, and the development of capital markets.

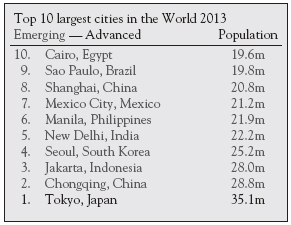

Also impressive is the increasing size of these economies. The growth of economic strength of the BRICS countries alone is leading to greater power to influence world economic policy. Just recently, in October of 2010 emerging economies gained a greater voice under a breakthrough agreement that gave six percent of voting shares in the IMF to dynamic emerging countries such as China. As a result China became the IMF’s third largest member. According to the IMF, and as depicted in Figure 2.2, by 2014 emerging markets are poised to overtake advanced economies in terms of share of global GDP.

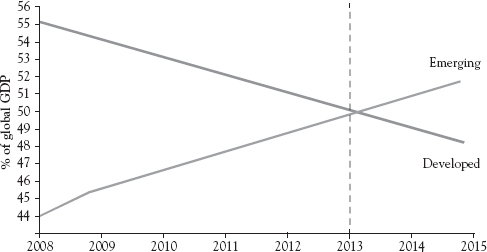

As of 2013, as Figure 2.2 shows, emerging markets already account for about 50 percent of world’s GDP and going forward, its contribution is expected to be higher than advanced economies. Not only are these economies enormous, but they are growing exponentially. As Figure 2.2 illustrates the divergence between the economic growth of emerging markets and advanced economies is projected to continue in the years to come. Figure 2.3 shows that since 2000, emerging markets have driven global GDP growth.

Figure 2.2 Advanced economies and emerging markets share of global GDP

Source: World Economic Outlook Database, International Monetary Found, October 2010

Figure 2.3 Emerging markets are driven global GDP growth for more than a decade (2000)

Source: IMF

The data indicates that emerging markets are now one of the main engines of world growth. As a result, emerging countries’ citizens have reaped the benefits of such rapid development with higher standards of living, fostering the growth of a huge middle-class, with discretionary income to spend in goods and services, and thus impacting advanced economies in a very positive way.

These billions of new middle class consumers in the emerging markets represent new markets for advanced economies’ exports and multinational corporations based in developed countries. Ford Motor Company, for example, draws almost 47 percent of its revenues from foreign markets, mainly from emerging markets. Also, strong growth in emerging markets increases the demand for those goods and tradable services where the advanced economies have comparative advantages.

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, as of 2011, the change in real GDP per capita in emerging markets has significantly surpassed that of advanced economies. Figure 2.4 shows a striking contrast. As of 2011 per capita GDP, has risen substantially faster in many emerging market countries as compared to advanced economies. The top 10 are all emerging markets in Asia, South America, and Eastern Europe. China topped the world with nearly a 35 percent change in real GDP per person, followed by India, which had a rate change of more than 20 percent. Argentina and Brazil also grew significantly, as did Poland, Turkey, and Russia. Advanced economies, however, are debt-burdened and have detracted. Ireland and Greece have declined more than 10 percent. During the same period, the United States had the seventh worst change in real GDP per capita.

Figure 2.4 The change in real GDP per capita in emerging markets has surpassed advanced economies by far

Source: Economist intelligence Unit, Analytics, IMF; JPMorgan; The Economist

These are known macroeconomic facts. Perhaps even more striking is the microeconomic evidence of the economic success of emerging markets in the last decade and beyond. For instance, according to Forbes’ Global 2000 ranking, four out of the 20 largest companies in the world, in terms of market value, are from emerging markets.2 From these four companies, two oil and gas firms, one Russian (Gazprom), and one Chinese (PetroChina) rank among the top 10. Also according to Forbes,3 seven of the 24 richest individuals in the world are from the emerging markets, including Carlos Slim Helu (3rd) from Mexico; Li Ka-shing (9th) from Hong Kong; Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Alsaud (13th) from Saudi Arabia; Mukesh Ambani (14th) from India; Anil Ambani (18th) from India; Azim Premji (21st) from India; and Lee Shau Kee (22nd) from Hong Kong.

If the present looks promising for emerging market economies, their potential future seems even brighter. According to available projections for long-term growth, based on demographic trends and models of capital accumulation and productivity, emerging markets are likely to become even more prominent in the world economy. Of course, political instabilities need to be accounted for, especially in the short term for some of these countries facing political turmoil. Nonetheless, a number of studies offer startling data regarding the growth prospects of emerging markets. According a study by Wilson & Purushothaman4 (2003), by 2025 the BRIC countries could account for over half the size of today’s six largest economies; in less than 40 years, they could be even larger. Other studies, such as Hawksworth5 and Poncet6 convey similar messages, notwithstanding some nominal differences.

Emerging market leaders are expected to become a disruptive force in the global competitive landscape. As emerging market countries gain in stature, new multinational companies (MNCs) will continue to take center stage in global markets. The rise of these emerging MNCs as market leaders will constitute one of the fastest-growing global trends of this decade and beyond. These MNCs will continue to be critical competitors in their home markets while increasingly making outbound investments into other emerging and advanced economies.

Many emerging market leaders have grown up in markets with institutional voids, where support systems such as retail distribution channels, reliable transportation and telecommunications systems, and adequate water supply simply don’t exist. Physical infrastructure, such as water supply, sanitation and electricity systems, and soft infrastructure, such as recruitment agencies and intermediaries to deal with customer credit checks, are still being developed, if they exist at all, in order to cope with the growing urban middle class.

Addressing such concerns will require several trillions of dollars in investments by 2020, which could be very good news for advanced economies and professionals with an eye on, and expertise with, international businesses. Meeting these needs will likely entail public-private partnerships, new approaches to equity funding and the development of capital markets.

Having learned to overcome the challenges of serving customers of limited means in their own domestic markets, these emerging MNC market leaders are already developing and producing innovative designs, while reducing manufacturing costs, and often disrupting entire industries around the world. As a result, these companies possess a more innovative, entrepreneurial culture and have developed greater flexibility to meet the demands of their local and bottom-of-the-pyramid customers.

Therefore, the developments we observe today, with the rapid rising of emerging markets outpacing advanced economies, are likely to be the precursor of a profound rebalancing in the distribution of world output in the very near future. Of course, it cannot be excluded that this process might well be “non-linear,” with episodes of discontinuity, perhaps also including financial crises somewhere down the line.

The Influences of the ASEAN Bloc

Many emerging market countries that previously posed no competitive threat to advanced economies now do. The financial crisis that started in mid-1997 in Southeast Asia, and resulted in massive currency depreciations in a number of emerging markets in that region, spilled over to many other emerging nations as far as Latin America and Africa. But such crisis since then has subsided, as these same regions were the first to recover from the latest crisis of 2008. The intense currency depreciation in Asia during the late 1990’s has positioned the region for a more competitive landscape across global markets.

According to an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report7 and as depicted in Figure 2.5,8 although these emerging market economies in Asia have experienced massive exchange rate depreciations, they also have reinforced their absolute cost advantages given the increasing importance of these economies in world trade.

Figure 2.5 Changes in Asian emerging market economies exchange rates since mid-1997

Note: Changes between 1 July 1997 and 18 March 1998.

Countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea, which were impacted the most during the 1990’s are now emerging market leaders, representing a major shift in the global competitive landscape. We believe this is a trend that will only continue to strengthen as these countries grow in size, establish dominance, and seek new opportunities beyond their traditional domestic and near-shore markets.

Meanwhile, advanced economies in the G-7 group are still struggling with indebtedness. The United States continues to deal with debt ceiling adjustments to cope with its ever-increasing government debt while the eurozone is far from solving its own economic problems. Conversely, despite inevitable risks and uncertainties, Southeast Asia registered solid economic growth in 2012 and continues to be on an upward trajectory for the foreseeable future, as China’s economy stabilizes and higher levels of foreign direct investment (FDI) are pouring in.

The ASEAN is an organization of countries located in the Southeast Asian region that aims to accelerate economic growth, social progress, and cultural development among its members and to promote regional peace. The region has undergone a period of substantial resurgence after the 1997–1998 Asian financial crises, and has been playing second fiddle to more industrialized economies in Asia-Pacific, which manage to attract the majority of capital inflows. What we’ve seen since the financial crisis, however, is that ASEAN has been showcasing its ability to recover and advance its position within global markets.

As of 2012, the ASEAN bloc is comprised of ten member states including Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. (See Figure 2.6.)

Studies carried out by the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI)10 suggest that the emergence of international production networks in East Asia results from market-driven forces such as vertical specialization and higher production costs in the home countries, and institutional-led initiatives, such as free trade agreements. For instance, the region has experienced significant growth in the trade of parts and components since the 1990s, especially with China, who is one of the important major assembly bases. In addition, the decline in the share of parts and components trade in several members of the ASEAN bloc, such as Indonesia and Thailand, indicates the increasing importance of the bloc countries as assembly bases for advanced economies such as Japan, and its multinational enterprises (MNEs). China and Thailand are becoming important auto parts assembly bases for Japan and other advanced economies, attracting foreign investments into those countries, raising their GDP, and contributing more to the emergence of international production networks than just free trade agreements. Figure 2.7 provides a list of ASEAN members and their respective GDP, as well as a comparison with major G-7 member states, with exception to China.

Figure 2.7 List of ASEAN countries GDP

Source: IMF Global Outlook 2012 estimates

Of course, the ASEAN region has had its fair share of risks and challenges, which unfortunately are not going away. ASEAN politicians, like politicians everywhere, occasionally cave in to populist measures. Since the crises of 2008 these populist measures have been present in both the advanced economies and emerging markets, with only the level of intensity as the single variant. But ASEAN’s deep commitment to macroeconomic stability, open trade, business-friendly policies, and regional cooperation has created the foundation for steady growth in those regions.

This is also true for many emerging market nations around the globe and in particular the BRICS. Nonetheless, the ASEAN region remains among the most attractive destination for foreign investors who are running out of options in other emerging markets. Its relative political and macroeconomic stability, low levels of debt, integration in East Asian production networks, and open trade and investment policies are giving the region a distinct advantage over other emerging markets around the world. As depicted in Figure 2.8, these countries have been growing at an average rate above six percent (in 2012) a year, with Indonesia and the Philippines exceeding GDP forecasts. Thailand, hit with devastating floods in 2011, has now recovered and is in full swing to achieve higher than expected GDP growth. The same goes for Malaysia, which has enjoyed the benefits of an expansionary election budget.

Figure 2.8 Asian Economic GDP growth based on purchasing power parity (Current International Dollar Billion)*

*An International dollar has the same purchasing power over GDP as the U.S. dollar has in the United States.

Source: International Monetary Found, World Economic Outlook, October 2012; Austrade

According to Arno Maierbrugger from Investvine,11 the ASEAN economy will more than double by 2020, with the nominal GDP of the regional bloc increasing from $2 trillion in 2012 to $4.7 trillion. The global research firm IHS12 argues that Vietnam and Myanmar are expected to reach a nominal GDP of $290 billion and $103 billion, respectively, by 2020, while Indonesia is expected to reach a projected nominal GDP of about $1.9 trillion. The report also says that overall emerging markets in Asia are expected to be the fastest growing in the world and will continue to expand. It estimated that GDP growth of emerging markets would exceed that of developed countries in 2020, continuing to expand thereafter.

Internal macroeconomic policies and structural reforms in the ASEAN region will continue to drive growth in the foreseeable future. The Philippines and Myanmar should see higher GDP growth as a result of earnest government efforts to improve economic governance. Myanmar, after 50 years of self-imposed isolation, fear, and poverty, has rejoined the international community, attracting fresh foreign investments, which should yield significant growth dividends.

In 2013, two parallel efforts toward trade integration, the ASEAN-driven Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and the U.S.-driven TPP, began vying for traction beyond the ASEAN bloc. Currently, the TPP is more advanced but faces important challenges before it can come to closure. Discussions on the RCEP have only just begun and also face significant obstacles, but progress could accelerate if an agreement on the basic parameters is reached soon. Although both of these trade agreements should be able to coexist, they not only include a set of advanced economies, which can be very beneficial to those countries, but also represent different philosophies as to how economic integration should be achieved.

The risk to emerging markets in the ASEAN bloc and the advanced economies partnership in trade, as in TTP, are the mounting tensions in the South China Sea, with China facing off against Vietnam and the Philippines. ASEAN’s diplomatic attempts to defuse the conflict have only succeeded in raising them even further. It is important now that under a new chair in Brunei, ASEAN countries find ways to settle their internal differences, agree quickly on a code of conduct for the South China Sea, and engage China early in the process so that it becomes an important stakeholder in its implementation and international trade.

Despite geopolitical risks in the region, one of the major catalysts for ASEAN’s accelerated growth is its relative low specialized labor costs. While estimates of cost levels in the manufacturing sector are not fully available, data from OECD and the IMF suggest that over the 1975 to 1996 period, China (including Taipei) and South Korea in particular, were able to maintain significantly lower levels of specialized labor costs than any other industrialized countries for which data exist. Important to note, as argued by Durant et al13 (1998), is the fact that while in the past these potential competitive advantages deriving from nominal exchange rate depreciations often tended to be eroded by rising inflation, there is a widespread sentiment that recent global economic and in-country financial policy developments might have reinforced the absolute cost advantage that emerging markets might have already compared to OECD countries, which makes these markets even more competitive internationally.

Such arguments are reinforced by the fact that in principle, competitiveness is normally correlated with companies, which can gain and lose market shares, and eventually even go out of business. The same cannot be said for countries. As P. Krugman (1996) argues14 countries cannot go out of business and therefore we should not care about competing countries. Nonetheless, in our opinion, countries still need to be concerned with shifts in market shares, since such shifts may indicate changes in the composition of country output and in the living standards of that nation. Hence, it is likely that labor cost levels in most other emerging market economies in the ASEAN bloc are also much lower, than in other nations, particularly advanced economies, as depicted in Figure 2.9.

We believe leading emerging markets will continue to drive global growth. Estimates show that 70 percent of world growth over the next decade, well into 2020 and beyond, will come from emerging markets, with China and India accounting for 40 percent of that growth. Such growth is even more significant if we look at it from the purchasing power parity (PPP) perspective, which, adjusted for variation, the IMF forecasts that the total GDP of emerging markets could overtake that of advanced economies as early as 2014. Such forecasts also suggest that FDI will continue to find its way into emerging markets, particularly the ASEAN bloc, but also to the fast-developing MENA bloc, as well as Africa as a whole, followed by the BRIC and CIVETS. In all, however, the emerging markets already attract almost 50 percent of FDI global inflows and account for 25 percent of FDI outflows.

Figure 2.9 Relative levels of unit labor costs in manufacturing

Source: OECD calculations based on 1990 PPPs. For details on the methodological aspects, see >OECD (1993)

As noted earlier, between now and 2050, the world’s population is expected to grow by 2.3 billion people, eventually reaching 9.1 billion. The combined purchasing power of the global middle classes is estimated to more than double by 2030 to US$56 trillion. Over 80 percent of this demand will come from Asia. Most of the world’s new middle class will live in the emerging world, and almost all will live in cities, often in smaller cities not yet built. This surge of urbanization will stimulate business but put huge strains on infrastructure.

The Influences of the BRICS Bloc

The original BRIC countries included Brazil, Russia, India, and China. Jim O’Neill, a retired former asset manager at Goldman and Sachs, coined the acronym in 2001 in his paper entitled Building Better Global Economic BRICs.15 The acronym came into widespread use as a symbol of the apparent shift in global economic power away from the developed G-7 economies toward the emerging markets. When we look at the size of its economies in GDP terms, however, the order of the letters in the acronym changes, with China leading the way (second in the world), followed by Brazil (sixth), India (ninth), and Russia (tenth).2 In 2010, despite the lack of support from leading economists participating at the Reuters 2011 Investment Outlook Summit,16 South Africa (28th) joined the BRIC bloc, forming a new acronym dubbed BRICS.17

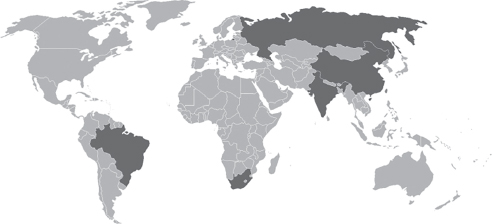

Figure 2.10 The BRICS countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa

It has been difficult to project future influences of the BRICS on the global economy. While some research suggests this bloc might overtake the G-7 economies by 2027,18 other more modest forecasts argue that while the BRICS are developing rapidly, their combined economies could eclipse the combined economies of the current richest countries of the world by 205019. In his recent book titled The Growth Map: Economic Opportunity in the BRICs and Beyond,20 O’Neil corrects his earlier forecast by arguing the BRICS may overtake the G-7 by 2035. Such forecast represents an amazing accomplishment considering how disparate some of these countries are from each other geographically and the differences in their culture, political and religious systems. Figure 2.10 illustrates the BRICS geographical locations on the globe.

Notwithstanding these uncertain economic forecasts, researchers seem to agree that the BRICS have a major impact on their regional trading partners, more distant resource-rich countries, and in particular advanced economies. The ascent of these formerly impoverished countries is gaining momentum, and their confidence is evident. Former Chinese Premier, Wen Jiabao, stated in 2009 that China had “loaned huge amounts of money,” to the United States, warning the United States and others to “honor its word” and “ensure the safety of Chinese assets.” The former Prime Minister of India, Manmohan Singh, has blamed the “massive failure” of the global financial system in 2008 on authorities in “developed societies.” His peers all name the United States specifically.

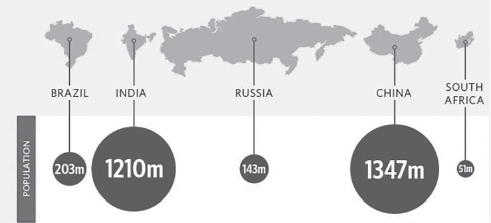

Figure 2.11 BRICS account for almost 50 percent of world population

Source: Population Reference Bureau

Vladimir Putin, as the fourth president of Russia scorns “the irresponsibility of the system that claims leadership,” while Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, former president of Brazil, in an interview with Newsweek magazine during the G-20 Summit in London, said the United States bears the brunt of responsibility for the crisis, and for fixing it.21

No doubt, there is a lot of global macroeconomics synergy behind the BRICS, and the performance indicators are backing it up. As of 2012, these countries accounted for over a quarter of the world’s land mass and more than 46 percent of the world’s population,22 although still only account for 25 percent of the world GDP.23 (See Figure 2.11.) Nonetheless, by 2020, this bloc of countries is expected to account for nearly 50 percent of all global GDP growth.

Since its formation, it is clear the BRICS have been seeking to form a political club. According to a Reuter’s article, the BRIC bloc has strong interest in converting “their growing economic power into greater geopolitical clout.”24 Granted, the BRICS bloc does not represent a political coalition currently capable of playing a leading geopolitical role on the global stage. That being said, over the last decade the BRICS has come to symbolize the growing power of the world’s largest emerging economies and their potential impact on the global economic and, increasingly, political order. All BRICS countries are current members of the United Nations Security Council. Russia and China are permanent members with veto power, while Brazil, India, and South Africa are nonpermanent members currently serving on the Council. Furthermore, the combined BRICS hold less than 15 percent of voting rights in both the World Bank and the IMF, yet their economies are predicted to surpass the G-7 economies in size by 2032. This can only strengthen their position at the UN, IMF, and the World Bank.

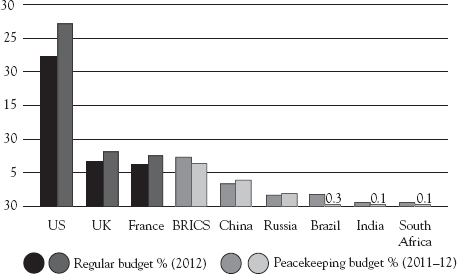

Figure 2.12 BRICS have increased their participation and contribution to UN budgets

As depicted in Figure 2.12, BRICS have stepped up their participation in the United Nations by donating large sums of money to its regular and peacekeeping budgets. Russia has led the bloc by holding the firm BRICS summit back in June of 2009 in Yekaterinburg, issuing a declaration calling for the establishment of an equitable, democratic and multipolar world order.25 Since then, according to the Times,26 the BRICS have met in Brasília, Brazil (2010), Sanya, China (2011), and New Delhi, India (2012).

In recent years, the BRIC have received increasing scholarly attention. Brazilian political economist Marcos Troyjo and French investment banker Christian Déséglise founded the BRICLab at Columbia University, a forum examining the strategic, political and economic consequences of the rise of BRIC countries, especially by analyzing their projects for power, prosperity and prestige through graduate courses, special sessions with guest speakers, Executive Education programs, and annual conferences for policymakers, business and academic leaders, and students.27

The Challenge of Global Influence

The BRICS’ continuing growing economic strength is advancing toward greater power to influence world economic policy. In October 2010, for example, emerging economies gained a greater voice under a landmark agreement that gave six percent of IMF voting shares to dynamic emerging countries such as China. Under this agreement, China will become the IMF’s third-largest member.

The differences between the BRIC bloc, in terms of values, economics, political structure, and geopolitical interests, far outweigh the commonalities. There are, however, fundamental commonalities, particularly with regard to mild anti-Americanism, and the overall internal and domestic challenges these countries face, including institutional stability, social inequality, and demographic pressures. The BRICS bloc is important for members in terms of the symbolism of creating for themselves an important role on the global stage, with a desire to wield greater influence over the rules governing international commerce, and economic policy.

Castro Neves, a founding partner at CAC Political Consultancy, and also contributing editor at The Brazilian Economy magazine, argues that Brazil’s “foreign policy priority is to consolidate its economic gains at the national level by building international influence and partners, and the BRICS group represents an important opportunity to realize that vision.”28 Fyodor Lukyanov, Editor of Global Affairs in Moscow, Russia, believes the bloc, although “unable to take a concerted stand on the new head of the IMF,” has an opportunity “to have a more influential, if not major, global role in the future.”*

We believe the absence of shared values between all BRICS members limits the global potential for the bloc. The inclusion of South Africa to the group may have been a good strategy, but the pull toward expanding the group to new members would dilute any cohesiveness it currently possesses.

The Influences of the CIVETS Bloc

The CIVETS acronym, which includes Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey, and South Africa countries, as illustrated in Figure 2.13, was coined by Robert Ward, Global Director of the Global Forecasting Team of the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) in late 2009.29 It was further circulated by Michael Geoghegan, President of the Anglo-Chinese HSBC bank, in a speech to the Hong Kong Chamber of Commerce in April 2010. These groups of countries are predicted to be among the next emerging markets to quickly rise in economic prominence over the coming decades for their relative political stability, young populations that focus on education, and overall growing economic trends. Geoghegan compared these countries to the civet, a carnivorous mammal that eats and partially digests coffee cherries, passing a transformed coffee bean that fetches high prices.

Figure 2.13 The CIVETS Bloc

The CIVETS bloc is about 10 years younger than the BRICS with similar characteristics. All of these bloc countries are growing very quickly and have relatively diverse economies. They offer a greater advantage over the BRICS, as they don’t depend as heavily on foreign demands. They also have reasonably sophisticated financial systems, controlled inflation, and soaring young populations with fast-rising domestic consumption.30

Geoghegan argued in 2010 that emerging markets would grow three times as fast as developed countries that year, suggesting that the center of gravity of the world growth and economic development was moving toward Asia and Latin America.* All the CIVETS countries except Colombia and South Africa also are part of O’Neil’s Next Eleven (N-11) countries. As depicted in Figure 2.14, this includes: Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Turkey, South Korea, and Vietnam. These countries are believed to have a high chance of becoming, along with the BRICS, the world’s largest economies in the 21st century.31

Figure 2.14 The Next-Eleven (N-11) Countries

Some critics argue that the CIVETS countries have nothing in common beyond their youth populations. What does Egypt have in common with Vietnam? Data also suggest that on the negative side, liquidity and corporate governance are patchy, while political risks remain a factor, as seen with Egypt in the past few years.

The Influences of the MENA Countries

According to the World Bank,32 the bloc, commonly known as MENA covers an extensive region, extending from Morocco to Iran and including the majority of both the Middle Eastern and Maghreb countries. The World Bank argues that due to the geographic ambiguity and Eurocentric nature of the term Middle East, people often prefer to use the term WANA (West Asia and North Africa)33 or the less common NAWA (North Africa-West Asia).34 As depicted in Figure 2.15, MENA countries include Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, North and South Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Yemen, West Bank, and Gaza.

The MENA bloc, regardless if known as WANA or NAWA (we’ll be using MENA throughout this book), is an economically diverse region that includes both the oil-rich economies in the Gulf, and countries that are resource-scarce in relation to population, such as Egypt, Morocco, and Yemen. According to the Middle East Strategy at Harvard (MESH) project at the John Olin Institute for Strategic Study at Harvard University, the population of the MENA region, as depicted in Figure 2.16, at its least extent is roughly 381 million people, about six percent of the total world population. At its greatest extent, its population is roughly 523 million.

Figure 2.15 The MENA countries (dark shade) and other countries often considered as part of the bloc (lighter shade)

Source: GreenProfit

Two years after the Arab Spring commenced, many nations in the MENA region are still undergoing complex political, social, and economic transitions. Economic performance indicators were mixed in 2012, while most of the oil-exporting countries grew at healthy rates; the same is not true for oil importing ones, which have been growing at a sluggish pace. However, due to the scaling-back of hydrocarbon production among oil exporters and a mild economic recovery among oil importers, the differences narrowed in 2013. In all, many of these countries are confronted with the immediate challenge of re-establishing or sustaining macroeconomic stability amid political uncertainty and social unrest, but the region must not lose sight of the medium-term challenge of diversifying its economies, creating jobs, and generating more inclusive growth.

Figure 2.16 MENAs population size and growth

Source: MESH & UN Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision (2007; http://esa.un.org/, accessed April 10, 2007): table A.2

The region’s economic wealth over much of the past quarter century has been heavily influenced by two factors: the price of oil and the legacy of economic policies and structures that had emphasized a leading role for the state. With about 23 percent of the 300 million people in the Middle East and North Africa living on less than two dollars a day, however, empowering poor people constitutes an important strategy for fighting poverty.

Modest growth is anticipated, however, across the region. According to the IMF,35 subdued growth in MENA oil importers is expected to improve in 2013, although such growth is not expected to be sufficient to even begin making sizable inroads into the region’s large unemployment problem. The external environment continues to exert pressure on international reserves in many oil-importing countries among the MENA bloc and remains a challenge. In addition, sluggish economic activity with trading partners, mostly advanced economies, in particular the eurozone area, is holding back a quicker recovery of exports. Elevated commodity prices continue to weigh on external balances in countries that depend on food and energy imports. Tourist arrivals, which have decreased significantly since the terrorist attacks on the United States in 2001, are gradually rebounding, but remain well below pre-2011 levels and before the global recession set in.

According to a new study reported in the Dubai-based Khaleej Times,36 the sunny region and its associated countries could solar power the world three times over. If such projections ever become reality, poverty may have a chance to be eradicated in the region. Countries that move fast, the study suggests, could have the competitive advantage. MENA countries, especially ones located on the Arabian Peninsula, as well as others like Jordan, Lebanon, and Israel are well positioned to take the lead in this industry. These countries are no strangers to the notion of solar energy. As the Khaleej Times article points out the countries in the MENA region have the “greatest potential for solar regeneration” supplying 45 percent of the world’s energy sources possible through renewable energy. Renewable energy sources of interest in this region include Abu Dhabi’s Masdar City, as well as its hosting of the World Renewable Energy Agency headquarters.

Funding for these projects may pose an issue. Foreign direct investment, according to the IMF, is expected to remain restrained and lower than in other emerging markets and advanced economies. Moreover, growing regional economic and social spillovers from the conflict in Syria is expected to add to the complexity of MENA’s economic environment. While oil-exporting countries, mainly in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), face a more positive outlook, there is still the risk of a worsening of the global economic outlook, particularly with advanced economies, which are major consumers of oil. Should this occur, oil exporting nations within MENA will likely face serious economic pressures. A prolonged decline in oil prices, rooted in persistently low global economic activity, for instance, could run down reserve buffers and result in fiscal deficits for the region.

The latest IMF’s World Economic Outlook projections suggest that economic performance in the MENA bloc will remain mixed. According to Qatar National Bank Group (QNB Group), this dual speed development should continue over the next few years, with the GCC countries as the driving force for growth in the MENA region and the main source of investment and financing. As shown in Figure 2.17, the Group forecasts MENA’s economy to grow 2.1 percent in 2013 and 3.8 percent in 2014. Note in Figure 2.17 that the overall forecast disguises a significant difference in performance between oil exporters, including the GCC countries, and oil importers. The 2012 restrained growth of 2.7 percent in MENA oil importers is expected to fall to 1.6 percent in 2013 and recover to 3.2 percent in 2014, which will not create enough jobs to reduce these countries’ large unemployment rates. Meanwhile, oil exporters’ healthy growth rates are projected to moderate this year to three percent as they scale back increases in oil production amidst modest global energy demand. Continued large infrastructure investment is expected to lead to a rise in economic growth to 4.5 percent in 2014.

Figure 2.17 MENA’s real GDP growth rates

In addition, the MENA countries in transition continue to face political uncertainty with the challenge of delivering on the expectations for jobs and fostering economic cohesion, which also deters growth. In particular, the Syrian crisis has had a strong negative impact on growth in the Mashreq region: the region of Arab countries to the east of Egypt and north of the Arabian Peninsula, such as Iraq, Palestine/Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, and Syria. Syria has a large amount of refugees straining the fiscal resources of countries like Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and, to a lesser extent, Turkey. A notable example is the more than 800,000 Syrian refugees who have already entered Lebanon, about 19 percent of the population, and have had a substantial impact on the already weak fiscal position of the Lebanese budget. Equally damaging have been the setbacks of the political transitions as well as the escalation of violence in Libya, Egypt and Tunisia, which have further deterred FDI and much needed economic reforms.

Looking ahead, MENA countries will continue on their path of economic transition owing primarily to the benign GCC outlook, which will continue to act as the locomotive for regional growth. That said, caution must be given to the external environment in volatile oil importing countries with spillovers from the Syria conflict. Finally, as important as it is now to focus on maintaining economic stability, it is critical for MENA governments not to lose sight of the fundamental medium-term challenge of modernizing and diversifying the region’s economies, creating more jobs, and providing fair and equitable opportunities for all.

1 The term was coined in 1981 by Antoine W. van Agtmael of the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank, http://www.investopedia.com/articles/03/073003.asp, last accessed on October 29, 2013.

2 According to United Nations 2011 ranking.