Steady Socioeconomic Development

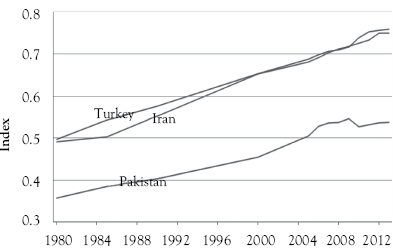

A remarkable achievement of Iran has been its steady social and human development in the last 40 years, particularly after the Islamic Revolution.1 According to the United Nations’ reports, significant improvements have taken place in Iran in areas such as health, literacy, poverty reduction, gender equality, education attainment, female and child mortality, and life expectancy.2 For instance, the adult literacy rate has increased from 14.5 percent in 1960 to 57 percent in 1988 and to 77.1 percent in 2001.3 The gap between adult men and women has been constantly narrowing. As a result of these improvements, the living standards have continuously increased and the Human Development Index (HDI) has grown from less than 0.6 in 1980 to 0.719 in 2001. Iran’s HDI value for 2012 was 0.742, positioning the country in the high human development category. In other words, after the Islamic Revolution between 1980 and 2012, Iran’s HDI value increased by 67 percent.4 Based on the same data, between 1980 and 2012, Iran’s life expectancy at birth increased by 22.1 years, mean years of schooling increased by 5.7 years, and expected years of schooling increased by 5.7 years.5 There have been major improvements in food security and as a result, the number of people suffering from hunger has been steadily declining. Indeed, Iran’s Global Hunger Index measured by the Food International Policy Research Institute has fallen from 8.5 in the 1990s to less than five in 2012. Similarly, Iran’s Gross National Income (GNI) per capita has increased by about 48 percent between 1980 and 2012.6 As shown in Figure 3.1 and 3.2, the long-term growth of Iran’s HDI has been well above a neighboring country such as Pakistan.

Figure 3.1 Trends in Iran’s Human Development Index between 1980 and 2012

Source : Malik.7

Figure 3.2 Trends in Iran’s Life Expectancy in comparison with Turkey and Pakistan between 1962 and 2012

Source : Malik.8

A Modernizing Society

According to Inglehart’s theory, the modernization process involves substantial changes including economic development, rising educational levels, higher occupational specialization, smaller families and higher rates of divorce, changing gender roles, and increasing emphasis on individual autonomy.9 In that sense, it is appropriate to categorize Iran as a modernizing society or a traditional society that is in transition towards modernization. In the 20th century and particularly during the Pahlavi era, substantial changes happened in the Iranian education, economy, politics, jurisprudence, public administration, and even dress codes. During this period, the government was determined to take harsh measures to push the country toward an accelerated and even forced modernization. These changes led to the pervasiveness of Western values in Iran that were, for the epoch, in conflict with the traditional values.10 At the time, many prominent Iranian intellectuals and religious leaders underlined the incompatibility between Iranian and Islamic culture and the Western modernity. For instance, in his book Gharbzadegi (Translated as Weststruckness), Ale-Ahmad (1962) a well-known writer and thinker insisted passionately on the corrupting influence of the West on the Iranian society.11 Some scholars like Samuel Huntington suggested that the Islamic Revolution of 1979 was essentially a backlash to the accelerated modernization and Westernization of Pahlavi era.12 According to this view, the Islamic Revolution emerged, largely, as a coalition of traditional forces to protect the traditional values confronted by modernization and Westernization process. After the Islamic revolution, the Iranian society has been affected by the interaction of both traditional and modernization forces. On the one hand, the religious and revolutionary agenda has pushed the society officially toward traditional values of Islam such as family, collectivism, deference to hierarchy, gender segregation, and religiosity. On the other hand, the same religious rule has led to the rise of modern values through public education, economic development, urbanization, and higher participation of women in labor market. For example, the Islamic government has extended the educational facilities to many rural zones and telephone, electricity, and health care services have become available in remote parts of the country.13 In 2003, Iran’s literacy rate was around 80 percent, and the country had more than 230 universities enrolling a total of nearly 1.6 million students.14 Similarly, the quality of public health care has been improving considerably after the Islamic Revolution.15 The weight of educated urban youth population has increased significantly, the number of women in schools and workplace has skyrocketed, and more importantly religiousness has become less attractive than before.16 With all these changes, the current Iranian society is very different from what the Islamic clerics had expected.17 Simply put, the effects of Islamic Revolution have been paradoxical. It seems that after three decades, the austere Islamic restrictions have backfired and the pace of modernization in Iran has been accelerated.18 Currently, there is a widening gap between the population and the formal political structure. While the society, as a whole, has moved toward modern and secular values in the past 30 years, the political structure has remained extremely traditionalist and Islamist.19 The reformists’ movement in the 1990s and the Green Movement in 2009 could be seen as examples of two unsuccessful movements that sought a more modern, pluralistic, and open society. One may speculate that the increasing gap between the formal structure and population’s culture may bring up major social movements in future.

The Paradox of Women’s Conditions

The improvement of women’s conditions began under the rule of Reza Shah Pahlavi in the 1930s and continued with his son Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi in the 1960s and the 1970s. During the Pahlavi era (1925–1979), the Iranian women were highly encouraged to participate in the public sphere and were granted the right to vote as well as the right to an equal voice in court. A family protection law was created in 1963 providing women with considerable rights in divorce matters and setting the marriage age for young girls at 18 years. Additionally, the women were offered the opportunity to attend all the educational and professional institutions.20 In short, before the Islamic Revolution, the government policies aimed at improving the women’s conditions by removing the traditional and religious barriers to their education, employment, and public participation.21 Brusquely after the Islamic Revolution (1979), much of the rights women had enjoyed were lost. The revolutionaries abolished many of the Pahlavi’s reforms and adopted such policies as the return of child custody to the father, the legalization of child marriage, the shift from an obligatory to the voluntary and contractual limitation on polygamy, and the authorization of men’s unilateral right to divorce.22 Also the Western-style dress was declared corrupt and the veil became obligatory. The Islamic government enforced gender segregation in most public places, women were required to ride in a reserved section on public buses, and on some occasions, adulterous women were given the death sentence. Despite all these conservative policies, in the postrevolutionary Iran, the women adequately managed to gain access to education, job market, and active public participation.23 Currently, after three decades of Islamic rule, the number of women graduating from Iran’s universities is overtaking the number of their men counterparts. The female literacy and school enrollment rates have increased tremendously and women make up 65 percent of all university students.24 Iranian women occupy positions in almost all fields and are involved actively in workforce. While Iranian law and politics openly favor men, Iranian women have a highly noticeable role in public life, much more noticeable than in many other Islamic or Middle Eastern countries. Despite all the apparent restrictions, the postrevolutionary Iran has produced a large number of prominent female artists, filmmakers, journalists, publishers, authors, scholars, mathematicians, engineers, researchers, physicians, scientists, lawyers, human rights activists, managers, and university professors.25 Therefore the condition of women in the postrevolutionary Iran seem very paradoxical. On the one hand, we witness the imposition of some harsh Islamic and traditional restrictions shortly after the Islamic Revolution; on the other hand, we find out that the Iranian women have had great achievements in different areas including education, business, and public participation.26 Simply put, the Islamic restrictions have led to women’s empowerment! There are two main reasons that can explain this paradox:

1.Modernization: Women’s empowerment and the subsequent gender equality are closely associated with the modernization process and its implications, such as the shift from agriculture to manufacturing or service-based economy, urbanization, increasing life expectancy rates, declining infant mortality and fertility rates, and the improved population health.27 For instance, declining infant mortality and fertility rates liberate women from the yoke of childbearing and create opportunities for women to actively participate in the social life.28 Likewise, a manufacturing or service-based economy demands more educated female workforce29 and urbanization in general leads to higher levels of gender equality. Therefore, we may suggest that despite all the postrevolutionary restrictions, the socioeconomic development taking place in the postrevolutionary Iran has acted as the driving force behind women’s empowerment.

2.The undesired effects of Islamization: We may propose that some of the postrevolutionary policies or restrictions such as sex segregation and women dress code (hijab) were in accordance with the Iranian traditional culture and for that reason turned out to be beneficial for a large number of women. After the Revolution, Iran’s Islamic government persuaded even conservative rural families that it is culturally and religiously appropriate to send their daughters away from home to study and work.30 Interestingly, for a traditional society such as Iran, the Islamic policies became liberators as they opened the school and workplace doors to the daughters of very conservative families who started to view women’s education and work as being religiously acceptable.31

In summary, while the Iranian women still face many restrictions, they enjoy more empowerment than their counterparts in other Middle Eastern or Islamic countries, and they seem relatively satisfied with their way of life. It is important to emphasize that the Iranian legal and political structures are considerably lagging behind the everyday realities and the Iranian women are lawfully facing multiple obstacles. The future will prove whether the Iranian women can improve the formal political and legal structures and enjoy the rights they deserve.

Iranian Intellectuals: Torn Between Islam and the West

Over the course of the past two centuries, Iranian intellectuals have been inspired and motivated by two major sources: Shia Islam and Western ideas. This is quite understandable, because since the 19th century, many young students were sent to the European countries such as France, England, Belgium, and Germany to get education in new sciences and technologies. Upon their return to Iran, these graduates who generally belonged to Shia Muslim families became critical of their homeland and its backwardness. In searching for a solution, some viewed the West as the perfect model to be applied in Iran. Others argued that the Western model is not applicable to the Iranian context and opted for adaptation of the Western technologies to their indigenous values. In addition, inspired by the Russian revolution, many intellectuals embraced Marxism and tried to contest the influence of Islamist clerics.32 The Iranian Communist Party particularly played a major role in shaping intellectual life by attracting a large number of writers, poets, translators, journalists, academics, artists, and high ranking scholars. After the coup in 1953, a new generation of religious intellectuals emerged. Disappointed by Western ideas, this group of intellectuals emphasized the importance of Shia Islam in the Iranian history and argued that the Iranian modernization should be based on original values of Islam. In some cases, there was an attempt to reconcile Islamic values with Marxist concepts of social justice and egalitarianism.33 While these intellectuals were influenced largely by Western ideas, they were basically close to clerics’ perspectives. Among this strand of intellectuals, Jalal Ale-Ahmad, Mehdi Bazargan, and Ali Shariati are recognized as intellectual pioneers of the Islamic Revolution.34 Under the influence of religious scholars such as Morteza Motahhari and Mahmud Taleghani, the Islamic dimension of intellectual life grew substantially and cast a shadow on the communist ideas. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the Islamists took control of the government institutions and harshly eliminated the influence of leftists, Marxists, and Western-inspired intellectuals. The outbreak of war with Iraq was another reason for the revolutionary government to attack nonreligious thinkers and eliminate them physically or ideologically. During the 1980s, the secular thinkers were sidelined and the Islamist strand took a radical position by criticizing the West for all ills and corruption in Iran and across the world.35 In the postwar 1990s, there were signs of moderation among some Islamist thinkers such as Mahammad Khatami who was elected president in 1997. For a while it seemed that the radical Islamist agenda could not provide cure for an ailing Iranian society. The poor performance of revolutionary government, a long and terrible war with Iraq, and increasing social and economic problems made reformism the dominant trend in Iran’s intellectual life during the 1990s.36 The controversial presidency of Ahmadinejad between 2005 and 2013, and exclusion of reformers from the centers of power and universities may be viewed as a counter attack on the reformism that apparently lost momentum with the election of President Rohani in 2013. Currently, reformism is still the dominant intellectual strand. The proponents of the reformist trend emphasize the importance of indigenous and Islamic values, but they openly question the applicability of Islamic guardianship and advocate some liberal values pertaining to civic society, individual freedom, women emancipation, and freedom of speech.

Family

For most Iranians, the primary building block of society is family, and marriage is a common and blessed convention to create a family. Family is associated with honor, social status, wealth, and success. For that reason, loyalty to one’s family is extremely important. Like other Middle Eastern countries, Iranian families are patriarchal, meaning that the head of the household is generally the husband or father who expects respect and obedience from the members of his family and is responsible to support them.37 Children are central to the family and receive a good deal of attention especially in the middle classes. Yet, they are supposed to respect elders, act in conformity with their expectations, and take care of them in their old age. Compared with Western families, children may remain dependent on their parents’ emotional or financial support even until their thirties. The relationship between husband and spouse is by and large much less egalitarian than Western societies. After the Islamic revolution, the government tried to revitalize some old fashioned practices in the Iranian families through changes in civil code and marriage regulation. For instance, according to the Islamic law women are denied the right to divorce their husbands. Despite all their efforts, the Islamic government did not succeed in restoring traditional family rules.

Marriage is considered an important path toward building a successful family and raising kids. In accordance with the traditional and Islamic values, premarital sexual relationship and cohabitation are not ethically acceptable and having children out of marriage is seen as improper. Most of the girls and boys stay with their families until marriage. The average ages at first marriage for women and men are 23 and 26 years respectively, however, there are some differences across the country and between small and large cities. For instance, the Baluch and Lur ethnic groups are marked by the lowest ages at first marriage and are more likely to have consanguineous and arranged marriages.38 In urban regions, wedding ceremonies are held lavishly as they are intended to show off financial and social status. Flower decoration, food, cake, the wedding dress, photography, and other services are becoming increasingly trendy and expensive in large cities. Conventionally, the bride’s family provides her with a dowry though the groom and his family are responsible for paying the wedding expenses and providing a home. Divorce is culturally undesirable, but in the recent years divorce rates have been increasing particularly in urban regions. There are other important cultural and structural differences between rural areas and large cities with regard to family issues. Families in large cities tend to be smaller and are characterized by higher levels of income, urban culture, higher level of literacy and education, and more modern values. In contrast, families in rural areas and small towns tend to be larger and are scored lower in education and income. Families issued from these areas are marked by more traditional and religious values. In rural areas, women have children shortly after marriage, but urban couples often delay their pregnancies to have more leisure time and money. Tests for genetic and contagious diseases are carried out before marriage and couples can use professional services including fertility and genetic counseling across the country.

Sexual Conduct

Khomeini had mentioned that the Revolution of 1979 was a return to puritan Muslim values. Accordingly, the Islamic government took some drastic measures to desexualize the society and fight what they called impurity, misconduct, and corrupt Western behavior. These measures were various and touched on social, political, cultural, artistic, and even private spheres of citizens’ lives. In the early 1980s, the morals police could arrest people in their own homes for accusations such as corrupt or immoral sexual behavior. Both the arrest and punishment remained very arbitrary and depended largely on the circumstances. The punishment could range from small fines to incarceration, lashing, and even execution. The campaign of Islamic government against immoral misconduct culminated during the war against Iraq. After the war and during Rafsanjani’s presidency (1989–1997), as a result of the liberalization of society as a whole, the government decreased the level of pressure on citizens. Moreover, the new generations who were entering their adulthood became increasingly moderate, and gradually distanced themselves from the orthodox revolutionary behavior. Faced with a young society and their sexual desires, the Islamic government desperately sought solutions. Subsequently, a range of quick fixes and superficial measures were promoted including temporary marriage and financial subsidies to young couples. Neither of these measures proved to be effective. Financial incentives were not considerable enough and they targeted the wrong groups. The idea of temporary marriage, which was suggested in Friday prayer ceremony by the ex-president Rafsanjani, was out of favor by the majority of people especially women, young, and middle class families. Even many clerics opposed to it as a provisional solution that could engender bigger social and cultural problems such as sexual violations, unwanted pregnancies, illegal abortions, and sexually transmitted diseases.

Overall, the conjugal and sexual behavior in the postrevolutionary Iran is marked by a combination of traditional, religious, modern, Western, and common sense practices. It is possible to identify three main types of sexual behavior within the Iranian society. Type 1 is the orthodox Islamic Republic recommendation. Accordingly, no heterosexual contact out of marriage is permitted, and both men and women should adhere to the strict puritan conducts and dress codes as outlined by the government. While this type of behavior has its roots in the Iranian tradition and Islamic teachings, it is not very popular among Iranians especially in the urban areas. Type 2 sexual conduct is marked by more laissez-faire and Western values and is increasingly popular among the postrevolutionary young generation. Finally, Type 3 is a middle ground between Types 1 and 2 and is based on common sense and pragmatism. As a general rule, while promiscuity is not widely accepted in the Iranian society, the common sense heterosexual socialization is widespread in the urban areas. Dating in the Western sense does not take place in Iran, but boys and girls could mingle and flirt in schools, universities, and parks. The concept of temporary marriage and polygamy are uncommon and disliked, and young girls’ virginity is still an important and sensitive issue.39 For many people, virginity is an indication of women’s purity and their future loyalty. However, the younger generations are becoming less sensitive to virginity and may negotiate it before marriage.

Dress Code: A Constant Battle

One of the most contentious issues about the postrevolution Iran is the imposition of an arbitrary dress code on all Iranians particularly on women. Shortly after the Islamic revolution, hardliners argued that an Islamic country should be 100 percent Islamic and waged a full-fledged war against all symbols of corruption. They took some strict and even irrational measures to impose a uniform dress code on women consisting of a loose coat and headscarf or chador in black or grey. Similarly, they put in place mainly implicit standards for a dress code for men. For instance, Western style, colorful, and short-sleeved dresses were banned. Faced with considerable resistance from the population, the Islamic government relied on paramilitary forces (Basij) and morals police to impose the so-called Islamic dress code and crack down on what was labeled as improperly-clad citizens. The streets of Tehran and large cities became the battlefield between improperly-clad men or women and the police forces. Many were arrested or cautioned by police over their dress, some were obliged to sign formal statements that they would do better in the future, and some faced court cases.40 It seems that even after 35 years of Islamic rule, the government and religious bodies have not been successful in implementing their intended dress code. The Iranian women have found new ways of expressing their individual freedom and in the past years the Islamic hijab has become less appreciated among ordinary Iranians. For example, women have begun to wear more fashionable colored dresses rather than dark chadors.41 Currently, despite some sporadic crackdowns, the Islamic hijab is much more lenient in comparison with that prevalent in the 1980s. Over the course of the past 10 years (2005–2014), women have gradually altered the standard form of their outfit and made it shorter, tighter, and more colorful. To express their discontent with the imposed dress code, young women have transformed the recommended dark headscarf into a fashionable shawl in different colors and designs that makes them even more attractive. The more Westernized women may expose body parts or choose sexy dresses but the traditional and religious women prefer modest and conservative dress codes with darker colors and little make up.42

Most of the Iranian men do not have beards, but since the Islamic Revolution (1979), beard has become a sign of association with religiosity or theocratic government. Growing moustaches has been conventionally very popular among men and has been connected with manhood and chivalry. While moustaches are still admired, it seems that in the past 20 years, they are becoming less popular. Ties for men in public places are forbidden and most men wear casual clothing like trousers and long- or short-sleeve shirts. Young men prefer jeans and t-shirts, but the religious men distinguish themselves by wearing loose shirts that are buttoned up. On the whole, Iranians dress well and are quite careful about what they wear. Their dress codes diligently communicate their tastes, their values, and whether they belong to modern, traditional, educated, bazaari, or conservative religious groups.

Education System: Learn to Leave

For many centuries, the primary and secondary educational schools in Iran were administered by clergymen. In the 19th century, with the advent of modern times, these schools found themselves under growing pressure as they could not adopt new sciences in their curricula. Unavoidably, the modern social and technical changes led to reform in the Iranian education systems and gradually some secular schools were established. Under the Pahlavi rule (1925–1979), Iran’s education system was rapidly modernized; all the religious primary schools disappeared, and the religious secondary schools were dedicated solely to training the clergy and Islamic scholars.43 Worried about the preservation of traditional and Islamic teachings, the clerics and conservative religious people expressed their criticism of the Western style education system. After the establishment of the Islamic Republic (1979), the transformation of schooling system in general and universities in particular has been a major preoccupation of the revolutionary authorities. The postrevolutionary transformation aimed at both politicizing and Islamizing education system in order to generate a new generation whose values and beliefs come in accordance with the ideology of the ruling power. Accordingly, the authorities took drastic measures to fire those teachers who were opposed to the Islamic Revolution, put certain restrictions on girls, changed the textbooks, and introduced a series of religious practices in schools. Despite all these measures, the postrevolutionary educational model kept almost the same Western structure that existed under the Pahlavi rule, chiefly in order to respond to technical and economic needs. Furthermore, the Islamic Republic apparently continued Pahlavi’s commitment to offer free, public, and mandatory elementary education to both boys and girls.

Currently, the schooling system consists of three cycles: primary, middle (guidance), and secondary education, which cover grades 1 to 5, 6 to 8, and 9 to 12, respectively. The middle cycle or guidance provides students with general education that will be used in choosing their concentration in the secondary cycle. The secondary education is divided into two main branches: academic and technical and vocational branches, which respectively lead to university education and job market. Iranian families spend extensively on educating their children considering it as an investment for their future. In the past 15 years, higher education has become very pervasive and 80 percent of high schools graduates enter universities. Due to a large number of applicants, admission to universities is through a nationwide entrance examination called koncour (from French concours). The koncour examination is very competitive and only the most talented students can enter state funded universities. In 2009, almost 1.2 million applicants took the konkour entrance exam. The last three years in high school are all about preparation for konkour. If the applicants are not among those accepted into prestigious state universities, then they may attend one of the private colleges or Azad Islamic Universities that exist across the country. There are more than 200 state universities and 250 institutes of higher education in the private sector, which is a large number going by the standards of developing countries. state-run universities are free and may pay some financial aid to their students, but private universities (Azad Universities) necessitate substantial tuition fees. In general, parents pay the costs of study and only a very small number of students work. The number of research institutions has grown dramatically since the Islamic Revolution. For instance, by 1982 there were 86 research institutions in the country, and 10 years later, in 2001, the number climbed to 191.44 Since the 1990s, Iran’s government has undertaken specific policies to reorient research towards industry and application.45 Nevertheless, education, success, and income do not always go together, and due to high unemployment rates many of the university graduates end up being unemployed or underemployed. Every year, large numbers of educated young Iranians leave the country to work or study in other countries mainly in Canada, the United States, and Australia. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Iran tops the list of countries in losing their academic elite, with a net loss of 150,000 to 180,000 specialists per year, which is equivalent to an annual capital loss of $50 billion.46 Another report by the World Economic Forum ranks Iran 107 out of 142 countries in retaining and attracting talented people.47

Youth

The youth had a major role in the revolution and establishment of the Islamic Republic. Many high ranking revolutionary officials were very young, sometimes under 30 years of age. Ironically, the Islamic Republic has had a tense relationship with young Iranians, especially those born after the revolution. Politically, the Islamic regime oppressed young dissidents from opposition groups, particularly from the leftist parties. At the social level, the youth have been restricted from civil liberties and have been subject to stern dress codes and guidelines. At the economic level, the youth have suffered from hyperinflation, unemployment, increasing cost of living, and lack of professional and educational opportunities. Most of the young Iranians compare themselves with their peers in developed countries and blame the government for all their social, economic, cultural, educational, and professional shortcomings. This attitude has been leading to an implicit opposition to the government policies and resorting to an underground youth culture. It is important to mention that there are major differences between urban youth and those in smaller towns and villages, as the former group is more Westernized.48 The urban youth persistently look for ways to reject harsh boundaries. While they remain mainly religious, the government extremism has pushed them towards a much more liberal orientation, which is in stark contrast with hard line clerics’ worldview. It seems that the younger generations are more hedonistic and do things that were not permissible for the previous generations.49 House parties, aggressive alcohol drinking, wild drug use, and sexual promiscuity are quite common behind closed doors in urban centers. These parties are considered not only as entertainment but also as political and ideological dissidence. On the whole, the typical urban Iranian youth are very different from their revolutionary parents who lived 30 to 40 years ago. Today, the Iranian youth are enlightened, disillusioned, and depoliticized. While they have a positive attitude toward the West in general and the United States in particular, they are extremely nationalistic. Despite all their economic or social hassles, they take great pride in being Iranian. They are receptive to Western modernity, but they think that there should be national solutions to all the problems of the country.