Business Environment and Management Practices

Open for Business?

While Iran represents a sizeable economy, the foreign direct investment (FDI) in the country has been very insignificant over the past decades. The World Bank data shows that inflows of FDI reached $909 million by 1978 but subsequently fell to $164 million in 1979 and $80 million in 1980.1 In 2007, the inflow of FDI in Iran hovered over $754 million, which is a fraction of neighboring economies such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia.2 Iran has suffered from a significant domestic capital flight mainly to the UAE and Turkey. What is more, Iran’s GDP has contracted by 25 percent in the past three years from 2011 to 2013 mainly due to international sanctions. In addition to the international sanctions, political frictions with the West, inefficient regulatory system, country risk, and lack of support from the government are among the major obstacles to FDI in Iran. To overcome the United States economic sanctions, Iran has been seeking investment from emerging and developing countries such as China, Russia, India, Malaysia, and Turkey. More recently and particularly after the presidential elections of 2013, Iran has moved to abandon its isolationist policies by letting foreign investors enter the country. In his first appearance at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in 2013, Iran’s new president, Hassan Rouhani, invited world policy makers and business leaders to invest in Iran and take advantage of the business opportunities of his home country.3 The Rouhani administration has clearly taken a probusiness stand and has been quickly reforming economic policies in the country.4 While contentions over the Iranian nuclear dossier are not fully resolved, it seems that foreign companies are planning for the time when international sanctions are lifted or relieved. In the same vein, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank assess that Iran’s economy will expand with an estimated growth rate of 1.3 percent and 1.98 percent in 2014 and 2015, respectively. It seems that these estimates take into account the effects of relaxation of existing sanctions, or at least, do not expect new punitive measures. Any peaceful resolution to Iran’s nuclear program will have huge business implications. In the past two decades, even despite the imposed economic sanctions, American and European companies have been seeking business opportunities in Iran through their intermediaries.5 The business opportunities in the country are abundant and include a wide range of industries and sectors such as oil, gas, automotive, agriculture, food processing, minerals, construction, education, manufacturing, and tourism.6 According to the Wall Street Journal, energy companies such as Total, Royal Dutch Shell and ENI, car makers such as Peugeot and Renault, and financial firms such as Deutsche Bank and Russia’s Renaissance Capital Ltd. are among those firms that are considering investment in Iran.7 Reportedly, Boeing has made its first sale to Iran after the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and managers from Peugeot and Total have been visiting Tehran on many occasions. As the French Finance Minister Pierre Moscovici has declared, France will have significant commercial opportunities in Iran if sanctions are lifted.8

Ease of Doing Business and Economic Openness

There is no secret that doing business in Iran is difficult. According to the World Bank reports, Iran is ranked 152 out of 189 countries in the Ease of Doing Business in 2013 and 2014.9 This ranking is an effective way to understand the business environment in a country. The ranking is based on many criteria; for example starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credit, protecting investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts, and resolving insolvency (See Table 11.1). This approach does not measure all aspects of the business environment that are important to businesses, but a high ranking generally indicates that the government has created an adequate regulatory environment conducive to operating a business.10 According to the World Bank report, the overall environment of doing business in Iran does not seem attractive. As shown in Figure 1.1, in comparison with neighboring countries such as Turkey, Pakistan, and Azerbaijan, the Iranian business environment is not very welcoming. The government has taken some measures to streamline the business activities, but the entrepreneurs still face various hurdles such as bureaucratic red tapes, bothersome regulations, and corrupt business behaviors. After taking office in 2013, President Rouhani has been advocating a more business-friendly attitude, but the effects of such reforms may take a few years to be felt by businesses.11

Table 11.1 The Ease of Doing Business (DB) in 2013 and 2014

|

Criteria |

DB 2014 rank |

DB 2013 rank |

Change in rank |

|

Starting a business |

107 |

101 |

−6 |

|

Dealing with construction permits |

169 |

171 |

2 |

|

Getting Electricity |

169 |

166 |

−3 |

|

Registering Property |

168 |

168 |

No change |

|

Getting Credit |

86 |

82 |

−4 |

|

Protecting Investors |

147 |

147 |

No change |

|

Paying Taxes |

139 |

138 |

−1 |

|

Trading Across Borders |

153 |

154 |

1 |

|

Enforcing Contracts |

51 |

52 |

1 |

|

Resolving Insolvency |

129 |

129 |

No change |

Source: World Bank’s Doing Business (2014).

Figure 11.1 The Ease of DB in Iran and neighboring countries

Source : World Bank Doing Business (2015).

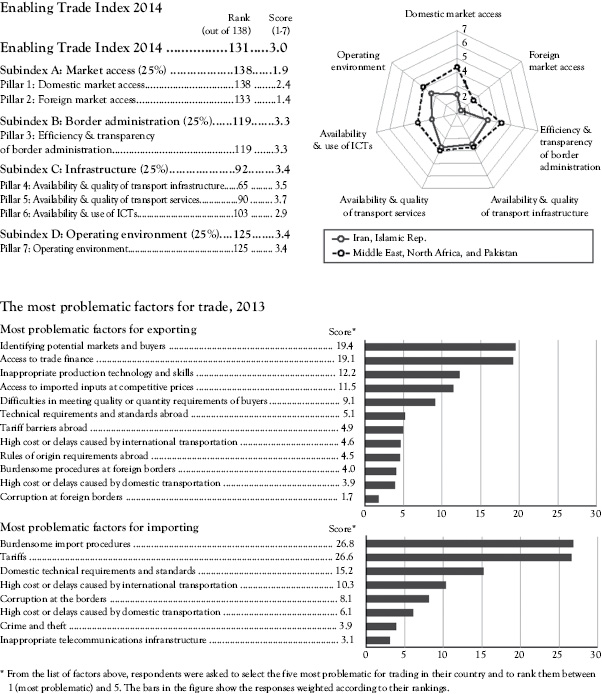

Another effective way to evaluate Iran’s business climate is to rely on the Enabling Trade Index (ETI) developed and measured by the WEF. The ETI is a comparative measure of international trade liberalization and is composed of four subindexes: (1) the market access subindex, (2) the border administration subindex, (3) the transport and communications infrastructure subindex, and (4) the business environment subindex.12 According to the Global Enabling Trade Report (2014) Iran is ranked 131 out of 138 countries that means the national business environment is extremely unsupportive of trade. As shown in Figure 1.2, Iran lags behind the Middle Eastern and North African countries in all aspects of the ETI, particularly with respect to foreign market access. While the international sanctions have been pinching Iran’s economy, the undesirable effects of mismanagement and poor planning should not be underestimated. According to the Global Enabling Trade Report (2014), identifying potential markets and buyers, access to trade finance, inappropriate production technology and skills, access to imported inputs at competitive prices have been recognized as the most problematic factors for Iran’s trade in 2013. Likewise, burdensome import procedures, tariffs, domestic technical requirements, and standards are considered as the most problematic factors for importing. Other alternative measures of trade and economic openness developed by the Fraser Institute and Heritage Foundation point to similar results. For example, according to the Heritage Foundation’s trade freedom scale, Iran is ranked 178 out of 181 countries in 2013.13 On the basis of this ranking, Iran is ranked last out of 15 countries in the Middle East and North African region, and its score is far below the world and regional averages. Lack of economic freedom and heavy state interference in economic activities may explain the stagnation and absence of trade, investment, and entrepreneurship.14

Figure 11.2 Iran’s ETI in 2014

Source : The Global Enabling Trade Report (2014).

Privatization

Shortly after the Islamic revolution (1979) the new government took some drastic measures to gain control over major enterprises and institutions through forceful nationalization and expropriation. The banks, insurance companies, car makers, industrial firms, transport and telecommunication corporations, large and medium-sized business, and educational institutions came under direct control of the state. Furthermore, the new government confiscated the assets of many individuals who were associated with the Pahalavi regime. Over time, the state-controlled institutions and enterprises suffered from unproductivity and became dependent on the government subsidies to run their operations. A decade later in the 1990s after the end of war with Iraq, economic liberalization in general and privatization in particular became attractive economic orientations once again. During this time, the government was seeking to stimulate economic growth and improve the efficiency of large organizations by reducing the government intervention in economic activities. The first Socioeconomic and Cultural Development Plan of the Islamic Republic of Iran that was prepared in 1990 advised the sale of some state-owned enterprises to the private sector and urged the government to reduce its control over production and economic activities. Accordingly, the government began to transfer ownership of many enterprises to the private sector through Tehran Stock Exchange, direct negotiation with the prospect buyers, and public auctions. Privatization through direct negotiation has been criticized for the lack of transparency and conflicts of interests.

A high degree of government intervention in economic activities has been linked to budget deficits, inflation, disturbance in optimal resource allocations, and unrealistic prices.15 As such, the successful execution of privatization in a country should result in greater efficiency and profitability, improvement of the firms’ performance, and the quality of their goods and services.16 Contrary to arguments that privatization increases efficiency and stimulates economic growth, multiple empirical studies show that in the case of Iran, privatization did not lead to any significant effects on the firms’ productivity, profitability, and efficiency.17 Despite its lofty aspiration, it is widely believed that the privatization process in Iran has not been very successful in attaining its goals. Instable economic policies, lack of appropriate legal frameworks, and above all, corruption and lack of transparency can be considered as major causes of the privatization failure in Iran.

Small and Medium-Sized Businesses

Despite the high involvement of the government in economic activities, majority of Iranian businesses, particularly in manufacturing sector, remain small (less than 50 employees) or medium-sized (50 to 249 employees). Small and medium-sized businesses (SMB) are accounted for about 60 percent of employment in the industrial sector. According to the Statistical Yearbook of Iran (1996–97), it is estimated that approximately 98 percent of all businesses are microenterprises with less than 10 employees. This is an astonishing number because it shows the absence of medium-sized enterprises, which amount to only 0.1 percent of the total number of enterprises. Obviously, the microbusinesses lack the necessary technological, financial, and managerial resources to become competitive on the international or regional markets. Furthermore, the microbusinesses cannot benefit from the economies of scale to reduce their prices and for that reason remain often uncompetitive. It has been recognized that those medium-sized businesses with 50 to 250 employees are usually more likely to get involved in international business activities. While licenses can be obtained by presenting a business plan, the lack of supportive environment and obstacles to raising capital and technology result in low growth of small business start-ups. As most of the start-up businesses are very small and rely on less than 10 employees, they often face the risk of bankruptcy and permanent shutdown. In the 1990s thanks to the postwar reconstruction and a boom in urban population, there was a quick and significant jump in the demand for various consumer products and services. These sociodemographic trends in conjunction with economic liberalization policies created favorable opportunities for Iran’s SMBs in the 1990s and the 2000s. Thanks to growing domestic consumption, Iran’s large industrial enterprises mainly car makers such as Iran-Khodro and Saipa outsourced the production of their components to SMBs. Furthermore, some SMBs particularly in food processing, textile, and furniture sectors have been involved in distribution, maintenance, and customer support activities of large enterprises. According to the Ministry of Industries’ projections,18 the share of the industrial SMBs in Iran’s exports could reach $56 billion by the year 2020. As the reliance of Iran’ economy on oil revenues has been declining in the past two decades, the role of SMBs in creating revenues is becoming increasingly essential. It should be noted that for these projections to happen, Iran should put in place adequate policies to increase the economic openness. It seems that in the recent years the growth and profitability of SMBs have been hampered by the overall Iranian business conditions notably international sanctions, capital shortage, and obsolete technology. Furthermore, the growth of Iran’s SMBs has been hampered by their low-quality standards and high prices as customers have often opted to consume imported goods. Another threat to the Iranian SMBs comes from increased competition of emerging countries mainly China. The SMBs are generally suffering from low productivity in comparison with other developing countries and for that reason cannot reduce the price of their products. For instance, the labor productivity rate for Iran is much lower than those for emerging countries such as Malaysia, China, and South Korea. In general, the SMBs are motivated by short-termism and quick profits and neglect the long-term reputation of their brands. For that reason, their products do not often meet international quality standards and some even fall short of reaching national standards that are relatively lenient. Low quality is one of the most important factors hindering the competitiveness of SMBs on the international and domestic markets and no effective quality assurance mechanisms and policies have been implemented in the country. Many Iranian micro or small businesses operating in traditional sectors such as furniture, garment, and food have been under increasing pressures of global competition. Many factors may explain the low level of SMBs success and growth, but among them the lack of an entrepreneurial culture, adverse business environment, red tape and complex regulations, and lack of supportive government policies seem notably significant. Furthermore, entrepreneurship receives very little attention in Iran’s educational system and the youth are not equipped with the skills and knowledge necessary for running a small business.

Banking and Financial System

After the Islamic Revolution (1979), all banks in Iran came in the possession of the government. Like other state-owned enterprises, the banks were mismanaged and suffered from grave inefficiencies. In the 1990s, after the implementation of privatization plan, some private or semiprivate banks and credit unions started working alongside the state-owned banks. Currently, there are about 10 state-owned and 20 private commercial banks and credit unions operating across the country. The state-owned banks are among the largest Islamic banks in the world and retain a considerable market share. As of 2011, the state-owned and private banks controlled 80 to 90 percent and 20 to 10 percent, respectively of the country’s market share.19 In 2009, Iranian banks accounted for about 40 percent of the total assets of the world’s top 100 Islamic banks. Three of the leading four Islamic banks are Iranian, namely, Bank Melli Iran with assets of $45.5 billion, Bank Mellat with assets of $39.7 billion, and Bank Saderat Iran with assets of $39.3 billion.20 Commercial banks are involved in operations related to checking and savings deposits and term investment deposits. They may use term investment deposits in business activities such as joint ventures, direct investments, and limited trade partnerships. Furthermore, they are involved in banking operations with state-owned institutions, government-affiliated organizations, and public corporations. The commercial banks are marked by an extensive network of local branches covering all provinces and cities. In 2004, there were about 14,000 commercial bank branches across the country.21 Iran’s banking system includes some banks specialized in certain sectors such as Bank of Industry and Mines, Export Promotion Bank, Housing Bank, and Agriculture Bank. Among these specialized banks, the Bank of Industry and Mines is the main provider of financing to SMB. Iran’s banks are famous for their high interest rates on term deposits and investments. For instance, the annual interest rates in state-owned and private banks for the period between March 2011 and March 2012 (Iranian year 1390) were hovering between 12.5 percent for one-year and 17.5 percent for four-year investments. While these interest rates seem highly exaggerated by the Western standards, they seem quite normal in a country marked by high annual inflation rates soaring between 15 to 30 percent. In the past decades, the banks have been paying 6 to 15 percent on deposits and charging about 20 to 27 percent on loans. In addition to term deposits, the Participation Papers (mosharekat) are very popular in Iran’s banking system. The Participation Papers are short-term bonds (from one to three years maturity) and have the same economic characteristics as fixed-rate conventional corporate bonds. More recently, they can be traded in an OTC fixed income market. Participation Papers are used to finance major projects and the profit must be calculated and distributed to the shareholders at the end of the project. During that time, dividend or interest is paid. The Participation Papers generally pay coupon rates of around 15 to 18 percent, which are 2 to 3 percent above bank rates, and due to their popularity are sold out shortly after their offering. All profits and awards accrued to Participation Papers are tax exempt. Many state-owned or private enterprises or organizations, such as Oil Ministry, Agriculture Bank, and Tehran Municipality, have issued hundreds of millions of dollars in Participation Papers. The interest rates charged for participation loans depend on the profitability of the project for which financing is required. In addition to Participation Papers, Sukuk is another fixed income instrument in Islamic banking that is similar to an asset-backed debt instrument. Iranian state-owned or private businesses such as Mahan Airlines and Saman Bank have used this instrument to raise more than $100 million.22

The Iranian banking system hinges on Islamic finance principles and has been striving to offer interest-free financial instruments. While the Islamic financial system offers some quickness in financing arrangements, due to its participatory nature, it involves more detailed financial disclosure than non-Islamic systems and requires client awareness of the banks’ risks, losses, and gains. Not all banks make their financial statements available and many offer results that are out of date. On the basis of their balance sheets, most of the Iranian banks are showing strong results in terms of high profits and quite low operating costs. However, a closer look at their assets reveals that many Iranian banks are suffering from bad debt. For instance, the amount of nonperforming loans in the banking system was estimated to be around $50 billion in 2010. The share of nonperforming loans in the Iranian banking system has risen from 10 percent in 2004 to 25 percent in 2010. The rapid devaluation of rial (Iran’s currency) between 2010 and 2012 pushed many depositors to withdraw their funds from their rial-denominated accounts to convert their money to hard currencies, gold, and other assets. As a consequence, many banks have suffered from massive cash withdrawals. Furthermore, the international sanctions have been crippling the Iranian banking system in the past five years (2011–2014) and have made international transactions impossible or extremely difficult. What is more, confidence in the banking system has been severely damaged as many cases of corruption, embezzlement, and fraud have been revealed. In September 2011, the news about a colossal fraud of $2.6 billion in Iran’s largest banks such as Bank Melli and Bank Tejarat shook the highest levels of Iranian banking system. Despite all these issues, Iranian banks are operating in a sizeable and growing economy and have continued to enjoy huge margins.

As the economy is dominated by the state intervention, the demand for investment and financing remains very limited. A source of problem is that bank loans and facilities are granted mainly to the large and influential enterprises and smaller borrowers remain largely at a disadvantage. This can generate serious hurdles for SMB to raise capital and finance their operations and expansion projects. In the recent years, the banks have modernized their operations and have adopted electronic payment equipment and systems. Due to international sanctions, the giant multinationals such as Visa and MasterCard are not present in Iran, but the local banks have been issuing more than 200 million banking cards including debit, credit, gift, and prepaid cards.

The Tehran Stock Exchange

The Tehran Stock Exchange was founded in 1967 and witnessed a solid growth in its first decade of operation thanks to the country’s political stability, rapid industrialization, and higher than average economic growth. After the revolution (1979), and particularly during war with Iraq from 1980 to 1988, the Exchange activities were substantially reduced and market capitalization fell to about $149 million. In the postwar period, the Tehran Stock Exchange received attention and with the privatization programs of the 1990s experienced a robust growth. Indeed, the government used the Tehran Stock Exchange as an instrument to transfer the shares of many state-owned enterprises to the private sector. Therefore, the number of listed companies increased from 56 in 1982 to 306 in 2000.23 Currently, the Tehran Stock Exchange is the second-largest in the Middle East, with a capitalization of about $150 billion.24 Iran’s economy is much more diversified than neighboring countries’ and offers companies operating in more than 35 industries including automotive, food, petrochemical, steel and industrial, oil and gas, copper, banking and insurance, and petrochemicals. As more state-owned firms are being privatized, individual investors are allowed to buy the traded shares on the Tehran Stock Exchange. About eight million Iranians own shares and 500,000 trade actively.25 Regardless of the introduction of supporting regulations, foreign investment remains insignificant as foreigners own only 0.1 percent of listed companies’ shares. In addition to ordinary investors, pension funds and institutional investors are active market participants. Despite the international sanctions and Iran’s political standoff with the West, the Tehran Stock Exchange has consistently shown robust performance over the course of the past decade. Indeed, the Tehran Stock Exchange has been one of the world’s best performing stock exchanges in the world between 2002 and 2013. The Tehran Stock Exchange Index has grown more than 500 percent in the last five years and despite some occasional corrections, the trend has been consistently upward.26 This rate of return is particularly astonishing because it does not correspond to the economic deterioration, soaring inflation, and high employment on the ground. The phenomenal growth might be due to a bubble that can burst sooner or later, but there are many other explanations. One alternative explanation for this amazing growth is the impact of privatization and transfer of state-owned shares to investors. It is argued that the entry of privatized state-owned enterprises to the Tehran Exchange increases the market capitalization and volume of trading and thus has a positive effect on the Index. Growing confidence in the Tehran Stock Exchange, entry of new investors, the intrinsic high value of many listed companies, and depreciation of Iran’s currency are other factors that may explain the robust growth of the Index.27 According to the Central Bank of Iran, almost 70 percent of Iranians own homes and possess large amounts of idle capital that they have invested in gold, real estate, vehicles, and foreign currencies. If Iran’s economy improves, these idle capitals are very likely to be directed towards equities.28 Furthermore, there are huge amounts of capital held by Iranian expatriates abroad, estimated at $1.3 trillion.29 Upon the improvement of Iran’s political and economic conditions, Iranian expatriates may invest part of their assets in Iran’s economy and particularly in the Tehran Stock Exchange. Foreign investors are almost absent from Iran’s equity market for some obvious reasons such as international sanctions and difficulty to transfer funds, but once the sanctions are lifted and geopolitical tensions are defused, they can rush into Iran and push the Tehran Exchange Index even higher. Considering all the potential internal and external flows of fresh capital into the Iranian equity market, the Tehran Stock Exchange could offer attractive investment opportunities. More recently, the Tehran Stock Exchange has initiated a modernization program to enhance market transparency and attract more domestic and foreign investors. With the new trading platforms, investors can conveniently make intraday trades through a relatively large number of accredited brokerage houses. The exchange has the capacity to handle as many as 150,000 transactions per day.30 The Exchange trading system offers details of past trading activities including prices, volumes traded, and outstanding buy and sell orders, so the investors can take informed decisions. While the Tehran Stock Exchange offers automated trading platforms and online real-time data, there are some concerns about the lack of transparency and sudden suspension of listed shares. Another problem is that only a limited number of independent private companies can benefit from using the Tehran Stock Exchange to raise capital and finance their expansion.

Corrupt Business Behavior

Iran is still a traditional country in which interpersonal connections and informal channels seem practical, whereas formal systems, official institutions, and procedures are considered less efficient and sometimes troublesome. As a result, the Iranian society tends to operate rather on the basis of personal relationships among people than on the basis of impersonal and dehumanized institutions. The use of informal channels is often associated with bending rules and taking advantages to which one is not formally entitled. The popular Persian term for this practice is partibazi, which is quite common in Iranian organizations. Those who receive a service, an advantage, or a special treatment via partibazi may choose to reciprocate indirectly or directly. The indirect approach involves compensating favor-givers by similar services, advantages, and special treatments. However, the direct approach involves paying bribes or commissions. Depending on the circumstances, this practice is called pourcaantage, raante, commission (from French pourcentage, rente, commission) or pool-chai (from Persian, meaning tea expenses). As a general rule, when partibazi does not imply any bribe or cash, it is not seen as a corrupt behavior. Favoritism may be regarded even as a positive or humane act toward friends, family, and acquaintance.

The Corruption Perception Index (CPI) developed by the Transparency International is a standard measure of corruption that is based on an aggregation of multiple surveys of public and expert opinion. The CPI offers scores for nearly 170 countries on an annual basis. According to the Transparency International, the CPI is “a composite index drawing on 14 different polls and surveys from seven independent institutions carried out among business people and country analysts, including surveys of residents, both local and expatriate.”31 Based on the Transparency International reports, Iran was ranked 144th out of 175 countries in 2013, 133rd out of 174 countries in 2012, and 120th out of 182 countries in 2011. In view of these results, Iran is recognized as a relatively corrupt country comparable to the Central African Republic, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, and Ukraine. These rankings confirm the facts on the ground, as in the past 10 years (2005–2014) Iran has been witnessing many cases of corruption and fraud at the highest level of government. In 2005, President Ahmadinejad took office seemingly by vowing to fight corruption at all levels of government, but ironically during his tenure the government transparency vastly deteriorated, and bribery, embezzlement, and misuse of public office became a common practice. In September 2011, the news of Iran’s largest embezzlement astonished citizens as many state’s banks and high ranking government officials including a close aide to President Ahmadinejad were allegedly involved in a $2.6 billion fraud. Despite their moral and Islamic rhetoric, a large number of government officials are well known for involvement in corrupt business behavior including bribery, embezzlement, and misappropriation. What is more, Iran’s judicial system is highly influenced by political forces and lacks transparency and decisiveness.32 The fact that many important positions in the economy are occupied by personalities or organizations connected to the powerful Revolutionary Guard may explain the prevalence of embezzlement.

Labor Market and Working Conditions

Iran’s population experienced an extensive growth during the 1980s at an average annual rate of 3.9 percent. Since then the population growth has been declining drastically and currently Iran has the slowest rates of population growth among all the Middle Eastern countries. Those children born in the 1980s have been entering the labor market in the recent years. It is estimated that around 800,000 young people enter the labor market each year.33 In addition to the population growth, young women are increasingly more educated and therefore are added to the number of new job seekers. The female participation in the labor market was negatively affected by the Islamic Revolution in the 1980s, but rose substantially in the 1990s and is projected to rise in the coming years.34 The bulk of unemployed people belong to the age group of 20 to 29.35 The new job seekers are mainly more educated than their predecessors and naturally have higher expectations. High schools focus on preparing students for college and generally do not provide the students with the required skills for a profession. The youth spend a long period of time, sometimes a few years, for the university entrance preparation. In general, Iran’s labor force is engaged in manufacturing, construction, agriculture, services, transportation, communication, and finance. Working conditions depend on the sector and the nature of business activity. In public sector the working conditions are better, work stress is lower, and employment security is higher. While the private sector jobs are less stable and more demanding, however, they may offer more generous salaries. Iran’s labor laws touch on all labor issues such as hiring, compensation, severance, unemployment insurance, minimum standards, and dismissal. Due to their inflexibility, the Iranian labor laws tend to be rather employee-friendly, and to some extent, discourage the employers from hiring new applicants. A typical working day starts at 8:00 am and ends at 4:00 pm. The work week in Iran consists of 44 hours from Saturday to Wednesday and half days on Thursday and Friday is a public holiday in the country. In addition, there are roughly 25 days in a year as official holidays.36

Women in Workplace

Men are still considered as the family breadwinners and are responsible for their household expenses. For that reason, the women unemployment rate is higher and women generally have lower incomes than their men counterparts.37 Nevertheless, the habitual image in the west of Iran being repressive towards women is not appropriate.38 Iranian women may hold offices and conduct business and there is nothing to prevent them from doing so, on the condition that they do not violate the codes of conduct as prescribed by the government.39 Women are mainly working in such sectors as education, health care, and government offices. In rural areas, many women participate in agricultural activities or contribute to the family income by knotting carpets.40 While employed women contribute to their household well-being, it is common for them to spend their income shopping for themselves or saving the money for their future needs. Over the course of the past 15 years, many of the women’s restrictions have been gradually relaxed and women are present in most occupations of their choice including managerial and professional positions.41 In 2005, except for technical and engineering studies, women outnumbered men in all academic disciplines.42 It may seem paradoxical, but imposing the Islamic dress (hijab) has led to growing presence of women in all spheres of the society. One may suggest that as the Islamic dress (hijab) is in conformity with the Iranian conservative culture, it provides traditional women especially those working in rural areas with more flexibility. In 2004, women accounted for 33 percent of the country’s labor force.43 In the same year, approximately 13 percent of senior officials, legislators, and managers were female.44 These numbers are very promising, because they are the highest in the Middle East and indicate a steady progress after the Islamic Revolution.

Human Resources Management

Selection and Staffing

Large organizations advertise job vacancies and conduct professional interviews to select the best candidates, but the results of their selection are generally affected by connections and favoritism.45 It is quite common to see someone who has been employed as a favor towards a family member, acquaintance, or colleague.46 Among different selection criteria, education and university diploma receive a good deal of attention even if they are not directly related to the job requirements. Other important criteria in the selection process may include professional experience, technical skills, and personal conduct of the candidate in his previous positions.47 In general, the state-owned organizations pay attention to the candidates’ compliance with Islamic and revolutionary values and behaviors. Only those who conform to the widely-accepted Islamic and revolutionary guidelines are selected by the state-owned organizations and government agencies. The government employers often require an entrance exam, interviews, and intrusive background checks, which might look into the candidate’s family background and their commitment to religious beliefs and practices.48 Checking the candidates’ political conformity is often a separate procedure that takes long time and might be evaluated by those who are not concerned about candidates’ professional capabilities. Such restrictions have underprivileged skillful workforce for more than three decades and have resulted in increasing inefficiency particularly in public sector and state-owned companies. In large organizations, the criteria for promotion are based on a wide range of behaviors that are not connected to performance or professional capabilities.49 Nevertheless, the selection process in the private sector could be quite different. In most of private businesses, professional experience, qualification, technical skills, education, and fluency in English and other languages are considered the key success factors.

Training and Development and Performance Appraisal

Job seekers are abundant, young, and well-educated but often do not meet the job market requirements. The mismatch between the job seekers’ qualifications and job requirements may be attributed to the Iranian education system that emphasizes theoretical aspects. The typical Iranian worker has a good base of theoretical education that may not be useful for potential employers. Furthermore, there is a constant pressure from family and society to study in such fields as engineering or medicine, but many graduates end up working in entirely different jobs.50 Large organizations often have training centers to enhance employees’ competence. The training programs cover a wide range of topics such as technical, managerial, and clerical skills. While most of the organizations recognize the importance of training and development programs, they do not take enough time for planning and preparation. Appraisal is not a common practice in Iranian organizations and those managers involved in appraisal performance hardly rely on systematic methods. An important issue in the appraisal process is the extent to which criticism is accepted. In traditional cultures such as that of Iran, people attach too much importance to interpersonal relations and negative feedback can bring about many problems for both, managers and subordinates.51

Compensation

The compensation policies in large organizations or government agencies are not closely related to performance as the preference for fixed pay is very widespread.52 By contrast, variable pay is used mainly in young and small enterprises that are concerned about their productivity and growth.53 Many Iranian organizations regard seniority as the major criterion for pay increase and promotion. This orientation is in conformity with the traditional cultural values cherishing past experience and elderly people. Indeed, seniors are often viewed as savvy, experienced, and knowledgeable.54 Another criterion for pay increase is the level of education. People with higher levels of education get more chances not only in recruitment but also in promotion. In addition, there is considerable difference between compensation packages intended for people working at the top of an organization and those working at entry levels. All active personnel qualify for pension plans that vary depending on the length of their employment, their contribution, and the nature of their work. In general such pension plans disburse monthly payments to men at age 65 and to women at age 60; however, employees working under difficult conditions and in physically demanding environments may be eligible for early retirement.

Leadership

Culturally, Iran is ranked high in the hierarchical distance.55 The effects of high hierarchical distance in organizational behavior and leadership appear as top-down management, authoritarian decision-making, and hierarchical structure of reward systems.56 Furthermore, high hierarchical distance and family-orientation of the Iranian culture encourage a paternalistic management or leadership style. Paternalistic management can be considered as an authoritarian fatherliness in which the responsibility of managers extends into private lives of their employees.57 Paternalistic managers consider it their function to protect and solve personal or familial difficulties of their employees both inside and outside of the organization.58 For instance, it has been reported that Iranian employees expected superiors to help them in a variety of issues such as financial problems, wedding expenses, purchasing of new homes, illness in the family, education of children, and even marital disputes.59