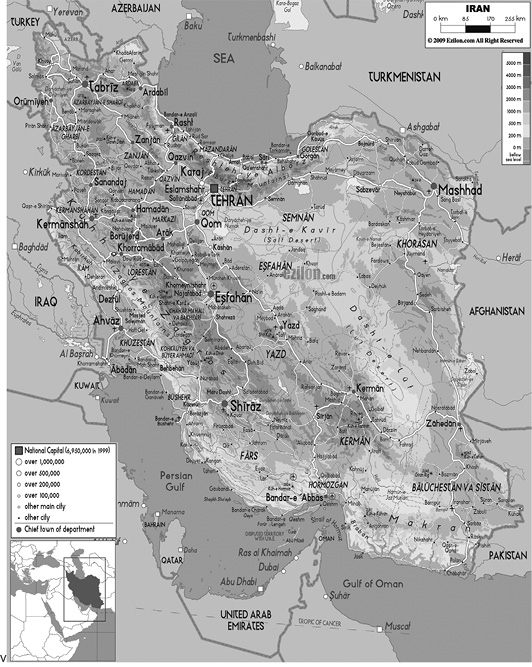

Physical Geography

Iran or Persia is located in southwest Asia. As shown in Figure 1.1, Iran shares land and sea borders with 15 countries; land borders with seven countries namely Armenia (35 km), Azerbaijan (611 km), Turkmenistan (992 km), Turkey (499 km), Iraq (1,458 km), Afghanistan (936 km), and Pakistan (909 km); and sea borders with eight countries including Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman in the Persian Gulf and Kazakhstan and Russia in the Caspian Sea.1 With an area of 1,648,000 square kilometers, Iran is ranked 16th in size among the countries of the world. Iran is highly diverse, especially in topography and climate. It comprises 14 percent arable land, 8 percent forest, 55 percent nonarable pastures, and 23 percent desert. Iran is one of the most mountainous countries of the world and hence major cities, including the capital, Tehran, are located in the foothills. The country has two main mountain chains surrounding the central Iranian plateau. Lowland areas are mainly along the Caspian coast, in Khuzestan Province, and along the coast of the Persian Gulf.2 The largest mountain chain is Zagros that stretches from the border with Armenia in the northwest to the Persian Gulf and has several peaks over 4,000 meters high. The Alborz Mountains in the north and northwest run along the south shore of the Caspian Sea. The Mount Damavand with a height of 5,671 meters is located in the center of the Alborz chain. The two mountain chains meet at Tabriz, beside Lake Orumiyeh in the Iranian portion of Azerbaijan.3 The Iranian Plateau is located in between these two mountain chains and covers over 50 percent of the country. Toward the east of the Iranian plateau there are two large inhabitable deserts called Dasht-e Kavir and Dasht-e Lut. The cultivable area of the central plateau is estimated to be about 31 percent of the total area. At the lowest elevations, the land is mainly dry, but as elevation rises, surfaces of sand and gravelly soil gradually merge into fertile soil on the hillsides. Between 1990 and 2010, the cultivable area of the central plateau has become dryer. The Alborz and Zagros mountains have deeply affected the socioeconomic conditions of the country since they surround agricultural plateaus and urban settlements. Historically, the plateaus have been isolated from each other and organized, independent urban settlements are found there. The mountains also impede easy access to the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea and for centuries have acted as physical barriers protecting the Iranian heartland from the raiding Turkish hordes of the north and the Arabs of the south.5

Figure 1.1 The physical map of Iran

Source : Ezilon maps.4

Natural Environment

The country is rich in mineral deposits; in particular petroleum and natural gas and also coal, chromium, copper, iron ore, lead, manganese, and zinc. Despite this natural generosity, disasters and especially earthquakes frequently occur in Iran. Tehran has at least five or six significant fault lines, and experts believe the city is at risk of major earthquakes.6 Iran is also frequently prone to drought, floods, dust storms, and sandstorms. The most productive agricultural land is located close to the Caspian Sea and makes up about 5.5 percent of the country’s total land area.7 Over the course of the past two decades (1970–2010), there has been rapid urbanization and vehicle emissions and industrial operations have resulted in poor air quality in major cities. Tehran and other large cities are vastly polluted and pose major health risks to their inhabitants. According to the World Health Organization—four Iranian cities namely Ahvaz, Kermanshah, Sanandaj, and Yasouj—were ranked among the world’s most polluted cities in 2010.8

Most of the country, especially the eastern deserts, suffers from lack of water resources and receives little rainfall. The exceptions are the higher mountain valleys of the Alborz, Zagros, and the Caspian coastal plains that receive heavy precipitations.9 The Alborz and Zagros mountains act as natural barriers and make the Iranian plateau very dry particularly in the central and southeastern part of the country. There are no major rivers in the country and the only navigable river is Rud Karun, which is 830 kilometers long. Other rivers include Sefid Rud (1,000 km), Karkheh (700 km), and Zayandeh Rud (400 km). The largest inland body of water is Lake Orumiyeh, which is salty and shallow and is located in northwestern Iran. In the recent years (2002–2015), Lake Orumiyeh has lost large amounts of water, and according to experts at Iran’s environmental agency, the lake contains only 5 percent of the amount of water it did just 20 years ago.10 There are also several connected salt lakes in the province of Sistan-Baluchestan. During the past three decades (1980–2010), industrial and urban wastewater runoff has severely contaminated rivers and coastal waters in the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea.11 Since ancient times, the problem of water supply has led Iranians to design efficient techniques for harnessing limited water resources. For instance, some 3,000 years ago the Persians invented the qanat or underground aqueducts that brought water from highlands to the surface at lower levels by gravity.12 Dams have always played an important role in harnessing Iran’s precious water reserves.13 Historically, the lack of water resources has had a very deep effect on the Iranian society. For instance, in the Persian language the word water (aab) and its derivatives such as aabad are used as synonyms for development, growth, and prosperity. The shortage of water supply is recognized as a major factor that has hampered the agriculture, and by extension, the socioeconomic development. Moreover, due to lack of major rivers, transportation across the country has been traditionally very slow and difficult. A combination of smart irrigation systems, canals, dams, and traditional architecture has allowed Iranians to settle in the arid central and southwestern parts.14

Thanks to its diverse topography, the country has variable climates. In the mountainous northwest, winter is extremely cold and snowy, spring and fall are mild, and summer is dry and hot. During winter, temperature of minus 22°F (minus 30°C) is recorded in the northwest and minus 4°F (minus 22°C) is experienced in central provinces. By contrast, in the south, winter is relatively mild and the summer is extremely hot reaching 131°F (55°C) in Khuzestan province. Overall, Iran has a continental climate with hot summers, cold to mild winters, and abundant sunshine. More than 2,000 plant species are found in Iran. The vegetation varies across the country according to topography, water, and soil mixture. Roughly one-tenth of Iran is covered by forest, which is mainly concentrated in the Caspian region and Zagros foothills. In mountainous regions, a wide range of vegetation is found such as oak, elm, maple, hackberry, walnut, pear, and pistachio trees. In addition, juniper, almond, cotoneaster, and wild fruit trees grow on the dry plateau. Willow, poplar, and plane trees grow in the ravines and thorny bushes cover most of the plains. Oases may have different kinds of vegetation such as vines and tamarisk, date palm, myrtle, oleander, acacia, willow, elm, plum, and mulberry trees. In marshes and plains, pasture grass is abundant during spring season. Wildlife of Iran is relatively diverse and consists of many species such as leopards, bears, hyenas, gazelles, rabbits, wolves, jackals, panthers, foxes, stork, eagles, and falcons. Main domestic animals include sheep, goats, cows, horses, donkeys, and camels. Due to massive urbanization, the population of some of wild species has substantially decreased. The Persian leopard is the largest of all the subspecies of leopards in the world and lives in the Alborz and Zagros mountains. A wide variety of reptiles, toads, frogs, tortoises, lizards, salamanders, racers, rat snakes, snakes, and vipers are found in Steppes and deserts. Among birds, seagulls, ducks, and geese live close to the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf shores. About 200 varieties of fish live in the Persian Gulf and Caspian Sea. The Caspian Sturgeon is commercially very important and is used in the production of Iranian caviar.

Demographic Trends

Iran’s population is estimated to be 80,840,713.15 While the entire Middle East excluding Iran and Turkey has a population of 128.8 million people, the sheer size of Iran’s population can be seen as an important strategic factor in geopolitics and business matters. Motivated by religious reasons, shortly after the Islamic Revolution (1979) the government abolished family planning programs. In the 1980s, it was believed that children are a gift from God and that contraception should be discouraged.16 Moreover, during the war with Iraq (1980–1988), Iranian political leaders endorsed the population growth as a matter of comparative advantage. The rising casualty of the war was another reason that encouraged many middle-aged couples to procreate more children.17 Consequently, the population of Iran grew at an average annual rate of 3.9 percent between 1977 and 1986, one of the most rapid rates of population growth in the world at the time.18 Faced with the grave social consequences of the population growth, the government was obliged to adopt new family planning programs and subsequently, fertility declined dramatically after 1988.19 In the recent years (2000–2015), the population growth has declined sharply and Iran now has the slowest birthrate among all the Middle Eastern countries including Lebanon and Israel.20 In some Iranian provinces, the fertility has fallen below the replacement rate.21 There are many factors that explain this declining trend. In addition to government policies, it should be noted that Iran is a modernizing and urbanizing society. Over the course of the past 15 years (2000–2014), Iranians have changed their attitudes toward marriage and children, and subsequently the age of marriage has increased significantly.22 According to a report by Iran’s National Organization for Civil Registration, 48 percent of women and 46 percent of men were at the marrying age but had not married in 2012.23 More recently (2010–2015), the rapid pace of modernization and urbanization has made children less of a benefit and more of an economic burden for their parents.24 As the young people are increasingly in school, they tend to delay their marriage. In addition, it seems that Iranians are becoming more comfortable with the contraceptives and vasectomies.25 Thus, the decline in fertility rates may be attributed to a combination of factors such as inflation, unemployment, lack of affordable housing, success of the government family planning programs, legitimizing birth control, cultural and social modernization forces, and higher levels of education and urbanization.

Facing the sharp drop in fertility rates from more than six children per woman in 1985 to less than two in 2013, the country’s Ministries of Health and Medical Education are considering policies to promote the population growth. In 2013, Iran’s parliament has suggested a ban on vasectomies as the country seeks to boost its birthrate. At any rate, Iran is still a young country and almost 70 percent of its population is under the age of 35 but as illustrated in Figure 1.2, Iran’s age structure is showing signs of maturity. It is estimated that fertility rate will remain at 1.7 children per woman over the course of the next decade.26 While Iranian population is estimated to grow, the growth rate is projected to be among the lowest in the Middle East.27

Figure 1.2 Iran’s age structure as of August 2014

Source : CIA World Factbook.

These two demographic waves, first a sharp rise and then a sharp decline in the birthrates, are transforming Iran to a modern and sophisticated society that is strikingly different from neighboring countries like Pakistan and Iraq. One may speculate that as Iran’s population is becoming mature, the working-age population will grow larger relative to children. This may create opportunities for the population to accumulate saving, to educate, and eventually to move toward a knowledge-based economy characterized by more technical industries and higher living standards. Under these circumstances, economic development could take place quickly and result in a society marked by cosmopolitan, educated, and secular middle-class citizens.28

Settlement and Urban Geography

Iran is far from being a monolithic country. Iranians are rather divided along cultural, ethnic, and linguistic lines. Amazingly, the topography and the water supply determine the regions fit for human habitation, the character of the people, and their types of dwellings. Most of Iran’s population is concentrated across the north as well as in the western parts where farming is promising.29 Historically, the huge mountains, the narrow rivers, and the empty deserts have resulted in insular settlements and formation of distinct ethnicities and dialects across the country. During the 20th century, as a result of a rapid modernization, major networks of roads were constructed and different regions and provinces were interconnected. Subsequently, the Pahlavi Land Reforms during the 1960s resulted in substantial urbanization and massive migration from villages to large cities. The migration to Tehran was accelerated shortly after the Islamic Revolution because of the weakening economic conditions in the rural areas and small towns.30 In addition, there were many Iranian refugees from the Iran–Iraq War and Afghans fleeing the Soviet assault on their country who migrated to Tehran in the 1980s and the 1990s.31 As a result of these waves of migration, the urban proportion of the population increased from 27 percent to 60 percent between 1950 and 2002.32 In the 21 years from 1976 to 1996, the number of cities with a population of over 100,000 increased from 23 to 59.33 According to the United Nations reports, 80 percent of Iran’s population will be urban by 2030. 34

Tehran and other big cities have always attracted most of the resources and investments, and consequently, the gap between big and small cities has been growing steadily.35 A traveler can see considerable differences between urban and rural regions. While urban regions are marked by modernized commercial and industrial centers, rural regions have remained mainly poor and underdeveloped. High concentration of investment in several big cities, especially in Tehran, continues to attract many rural inhabitants from diverse ethnical backgrounds. New migrants generally become submerged in the Persian or Tehrani culture and dialect and quickly adopt urban lifestyle.36 In general, the Iranian urban inhabitants have smaller families, are more educated, and are less religious. Iranian cities are not managed independently; therefore, urbanization is a huge financial and managerial burden for the Iranian government. Large cities tackle an increasing number of issues such as appropriate infrastructure, housing, transport, sewage, water supply, education, health, security, and recreation services. Overall, the process of urbanization in Iran has led to an overconcentration of administrative, economic, social, political, and cultural activities in Tehran and also a few large cities.

The country is subdivided into 31 provinces (ostan), which constitute major administrative units and are run by appointed governors (ostandar). Tehran, the capital of Iran, lies at the southern side of the Alborz Mountains, in north-central Iran, and less than 150 kilometers south of the Caspian Sea. Tehran is a rather young city that became the capital at the end of the 18th century, and its importance drastically increased under the Pahlavi and the Islamic Republic with their highly centralized administrative and economic systems.37 Tehran has become the center of government institutions, industries, businesses, universities, hospitals, and political power. Tehran’s population has quadrupled from 1956 to 1996. An estimated 16.5 percent of Iran’s population lives in Tehran and more than 70 percent of the economic and financial resources are concentrated in this city.38 If the greater metropolitan area is included, the population of Tehran reaches 11 million.39 In Tehran, the physical slope of the land is an accurate measure of socioeconomic status as the rich reside in the higher northern parts while the poor live in the lower southern suburbs. As one moves from lower parts of the southern Tehran to the higher northern neighborhoods, the infrastructure, the roads, and even the air quality are progressively improved. The residents of southern Tehran are generally poorer and less educated, have larger households, and are more religious.40 A large portion of Tehranis are employed by the government agencies and work in the public sector. Many others work in manufacturing industries or in small firms and businesses.41 Since the 1970s, heavy traffic has been a major problem in Tehran causing air pollution and long delays. Motor vehicle emissions are estimated to cause about 70 percent of the air pollution and smog. More recently (2010–2014), due to international sanctions, the substandard fuel and older vehicles have contributed to the exacerbation of air pollution in Tehran and many other Iranian cities. Most of the year, the levels of pollutants are significantly above those recognized as safe by health standards making Tehran one of the most polluted cities in the world.42 It is believed that air pollution is a major cause of coronary artery diseases and different types of cancers in Tehran.

In addition to Tehran, other big cities include Mashhad, Esfahan, Tabriz, Shiraz, Karaj, and Bandar Abbas (See Table 1.1). Mashhad is the second largest city and is located 850 kilometers northeast of Tehran near the border of Turkmenistan. Mashhad is considered to be a holy pilgrimage site for Shia Muslims. Recent statistics (2010) evaluate its population to be over two million. Esfahan is an important city and is located about 350 kilometers south of Tehran. Esfahan is famous for classic architecture and is also home to major industries, including steel, armaments, medicine, and textiles.43 Tabriz is located in the northwest corner of Iran, near the borders of Azerbaijan and Armenia. Tabriz is the center of the East Azerbaijan Province, has a population of over 1.5 million, and is ranked as the fifth most populated and second largest commercial city. Thanks to its location as a western gateway of Iran, Tabriz has played an important role in Iran’s socioeconomic development. Karaj is the capital of Alborz Province and is situated 20 kilometers west of Tehran. Shiraz is 935 kilometers south of Tehran and is especially famous for art, architecture, and poetry.44 Shiraz has a very mild and pleasant climate. Bandar Abbas is the major port in southern Iran at the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf. Rail, air, and land routes connect Bandar Abbas with other cities. According to the Statistical Center of Iran,46 in 2012, Iran had six cities with a population over one million, 61 cities between 100,000 and one million, and 125 cities between 10,000 and 100,000. Over the course of the past decade (2004–2013), the government policies have resulted in an astonishing increase in the cost of living in urban areas. It is interesting to know that relative to income, housing costs for Iranian urban residents are among the highest in the world.47

Table 1.1 The list of the largest cities in Iran by population in 2012

|

1 |

Tehran |

7,153,309 |

16 |

Azadshahr |

514,102 |

|

2 |

Mashhad |

2,307,177 |

17 |

Arak |

503,647 |

|

3 |

Esfahan |

1,547,164 |

18 |

Yazd |

477,905 |

|

4 |

Karaj |

1,448,075 |

19 |

Ardabil |

410,753 |

|

5 |

Tabriz |

1,424,641 |

20 |

Abadan |

370,180 |

|

6 |

Shiraz |

1,249,942 |

21 |

Zanjan |

357,471 |

|

7 |

Qom |

900,000 |

22 |

Bandar Abbas |

352,173 |

|

8 |

Ahvaz |

841,145 |

23 |

Sanandaj |

349,176 |

|

9 |

Kahriz |

766,706 |

24 |

Qazvin |

333,635 |

|

10 |

Kermanshah |

621,100 |

25 |

Khorramshahr |

330,606 |

|

11 |

Rasht |

594,590 |

26 |

Khorramabad |

329,825 |

|

12 |

Kerman |

577,514 |

27 |

Khomeyni Shahr |

277,334 |

|

13 |

Orumiyeh |

577,307 |

28 |

Kashan |

272,359 |

|

14 |

Zahedan |

551,980 |

29 |

Sari |

255,396 |

|

15 |

Hamadan |

528,256 |

30 |

Borujerd |

251,958 |

Source: Based on the Statistical Center of Iran.45

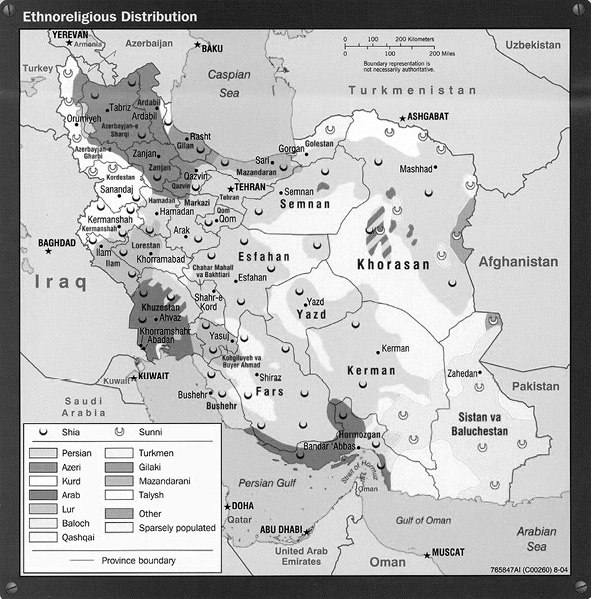

Ethnic and Linguistic Groups

Iran has one of the world’s most diverse ethnolinguistic groups gathered in one country. The main ethnic and linguistic groups consist of Persian (56 percent), Turk (Azeri) (24 percent), Gilaki (8 percent), Kurd (8 percent), Lur, Baluch, Arab, and Turkaman. (See Table 1.2). The ethnic and linguistic minorities account for half of the Iranian population and as shown in Figure 1.3, they reside generally far from the center and close to Iran’s borders.48 This diversity is surprising, because unlike many of its neighbors, Iran has a long history as a state. Indeed, other neighboring countries such as Turkey, Pakistan, and Iraq are ethnolinguistically more homogenous than Iran. Despite this ethnolinguistic diversity, Iran enjoys a significant national identity perhaps because of its history and religious homogeneity. Around 90 percent of Iranian population is Shia Muslim, and this may explain the unity of the country over time.

Figure 1.3 The distribution of ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups

Source : University of Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, 2005.

Persians are considered the main descendants of Iran’s tradition and history and have a dominant position in Iran’s politics, culture, education, and economy.49 According to Iran’s constitution, the official language of the country is Persian (Farsi), which is an Indo-European language and is taught and practiced in all schools from the first grade across the country. Many other languages are also spoken in Iran including Azeri, Kurdish, and Baluchi. All government business and public instruction is conducted in Persian (Farsi), and the state-run radio and television broadcasts are mainly in Persian but they offer limited programs in local languages. Over the past decades (1960–2010) the modernization programs of Pahlavi era followed by revolutionary agenda of the Islamic Republic have contributed to the prevalence of Persian language among other Iranian ethnolinguistic minorities even in small towns and villages.50 Many young migrants who arrive in Tehran or large urban centers adopt Persian to boost their social status and achieve professional success.51

The Old Persian language came to Iran around 1500 BC, evolved into Middle Persian, and after the Arab-Islamic conquest, changed to New Persian.52 The Arab-Islamic conquest introduced a large number of Arabic words into Persian and subsequently the Arabic script replaced the old alphabet, but the makeup of the language was largely preserved. This linguistic difference makes Iranians a distinct nation in the Middle East as the Persian language and literature have a great impact on the constitution of the Iranian national identity. Persian language creates a sense of belonging among all Iranians and contains a set of values, expressions, proverbs, and even cognitive structures that reflect the ancient Iranian culture. Persian is a literary language and is considered the essence of Iranian character.53 It is rich in proverbs, maxims, and metaphors that garnish communication and make the meaning sophisticated, pleasant, and nuanced. Furthermore, the Persian literature acts as a source of intellectual and artistic inspiration for all Iranians even for other linguistic groups. Iranians regularly read their classic literature and know by heart many poems of their literary masters such as Saadi, Ferdowsi, Rumi, Hafiz, and Omar Khayam. Torn between Arabic as the language of Islam on the one hand and English and French as the languages of modernity on the other hand, the Persian language has shown a good degree of resilience; it has found a way to survive, evolve, and innovate. Not surprisingly, both Pahlavi and Islamic Republic regimes have emphasized the significance of the Persian language as a foundation for national unity.

Azeris constitute more than 24 percent of Iran’s population and are considered the largest ethnolinguistic minority. They speak Azeri, are fervent nationalist Shia, and are found largely in northwestern Iran along the borders with the Republic of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Turkey. Despite their linguistic differences, the Azeris are well integrated into Iranian society, business, and politics.54 For instance, the current supreme leader Ayatollah Khamenei and many other high ranking officials and clerics are ethnic Azeris. As zealous nationalists, Azeris had major contributions to the formation of modern Iranian identity in the past 500 years. For instance, the founder of new Shia Iran dynasty, Shah Ismail Safavi, was an Azeri. Similarly, Azeris played a fundamental role in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1907). After the Islamic Revolution, the Azeris have participated in the Iranian government very actively as much as any other groups.

The Kurd ethnics are supposed to constitute around 7 percent of Iran’s population. They are generally Sunni Muslim and live in the northwest part of the country. Much of the Kurdish territory shared among Iran, Turkey, Iraq, and Syria had been historically administered by Iranian rulers between the 10th and the 16th centuries. In 1514, Iran lost most of this Kurdish territory to the Ottoman rule. The Kurdish language is closely related to Persian,55 but the Kurds have resisted the central government’s policies to incorporate them into the typical Iranian life. Occasionally, they have been involved in skirmishes with the central government before and after the Islamic Revolution. The Kurdish problem is not limited to Iran because the Kurds in Turkey and Iraq have much more radical claims. In 2003, after the invasion of Iraq by the American-led forces and the creation of a semiautonomous state in northern Iraq, the Turkish and Iranian governments have been concerned about the independent tendencies among their own Kurdish minorities. The ethnic Kurds are present in the private and public economic sectors as well as in Iran’s military and civilian establishments and apparently are becoming more integrated into the Iranian society.

The Arab minority is estimated to be around one million people who reside mostly along the Iranian–Iraqi border in the southwest Iran.56 The Arabs came to Iran during the seventh and eighth centuries and speak some dialects of Arabic. They are predominantly Shia Muslims and do not have serious civil or territorial claims. Most of the Iranian Arabs are mixed with the Persians and Turks and often intermarry. The Arab minority has been living in Iran for many centuries and has a cordial relationship with the rest of the country. During the Iran–Iraq War, the Arabs of Khuzestan fought on the side of the Iranians against the Iraqi Arabs.57 The Gilakis are other Iranian groups who speak a particular Persian dialect and are settled mainly in the Caspian Sea area.58 The Turkmen ethnics are estimated at less than 2 percent of Iran’s population, speak Turkic languages, are mainly Sunni Muslims, and reside in the northeast of the country. The Lurs are dwelling in the western mountains of Iran and consist of mainly seminomadic tribes. They constitute less than 1.5 percent of the Iran’s population and are supposed to be the descendants of the aboriginal inhabitants of the country. The Lurs speak some dialects of Persian language. The Baluchis comprise less than 1.5 percent of Iran’s population, are mostly Sunni Muslims, and reside in the Sistan-Baluchistan province along the Pakistan border.59 The Sistan-Baluchistan is believed to be the least developed part of Iran and is lagging behind in all socioeconomic measures such as employment and education. Due to tribal affinities of the Iranian Baluchis with their Pakistani brothers, the control over the province has been a daunting task for the central government. Generally, the Baluchis are not persecuted unless they are involved in illegal activities.60 In the past years (2008–2014), a rebel Baluchi group called Jundallah has attacked government officials and civilian targets. The Iranian government maintains that some foreign countries like Saudi Arabia entice such ethnic clashes.

The Conditions of Ethnic and Linguistic Minorities

In theory, the Iranian Constitution guarantees the rights of ethnic minorities,61 but in practice, Persians are mostly at an advantage to benefit from economic and social development programs. While the government does not discriminate against the race and origin,62 the ethnic minorities lag behind in employment, education, and economic opportunities. Since the 1970s the ethnic groups have increasingly entered into the mainstream Iranian society and have improved their standards of living. Both Pahlavi and Islamic Republic policies have been relatively successful in assimilating ethnic minorities into the Iranian society. The Pahlavi Shahs through modernization and coercion, and the Islamic Republic by revolutionary and Islamic programs, have tried to overcome the ethnolinguistic differences and build a strong national identity. It seems that these efforts have been quite effective. Overall, despite some sporadic events, Iranian minorities are not considered major threats to the political stability of the country. Azeri minority is so large that practically it is a core component of Iranian identity. Azeris are well represented in the government, the religious institutions, and Iran business community.63 The relationship between the Kurds and the Iranian state has been more problematic, partly because of geopolitics. While the Kurds are divided among Iran, Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, they have a strong affinity with Iranian culture and Persian language. Other minorities do not have any viable alternative to claim secession from the mainland. The solidarity of all ethnicities in the defense of Iranian territory during the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988) is an indication that Iran has mainly succeeded in building a solid national identity that surpasses ethnic and tribal cleavages.64

Religious Minority Groups

Under the secular and modern regime of Pahlavi dynasty, the religious groups were not essential in determining the minorities’ identities; however, it seems that under the Islamic Republic, the religious groups and affinities have gained more importance.65 Nearly 89 percent of Iranians including Persians, Azeris, and Gilakis are Shia Muslims and 11 percent are categorized as Sunnis, Christians, Zoroastrians, Jews, and Baha’is.66 According to Iran’s constitution, only three religious minorities are officially recognized, namely Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians.67 The followers of these three religions are permitted within the limits of the law to perform their religious rituals and ceremonies and to act according to their own canon in matters of personal affairs, marriage, and religious education. Sunni Muslims are the largest religious minority in Iran and include ethnic groups such as Kurds, Baluchis, and Turkmens.68 Also, it is estimated that a minority of Arabs and small communities of Persians in southern Iran are Sunnis.69 While Iranian Shias completely respect their Sunni brothers, they consider their religion less refined. Since the Islamic Republic hinges upon the Shia principles, the government does not welcome the public show of Sunni religion. 70

Baha’ism constitutes the largest non-Muslim minority in Iran. It is estimated that there are more than 350,000 Baha’is in Iran.71 Most of Baha’is are middle class urban Persians and are dispersed across the country. Baha’ism appeared as an offspring of Shia Islam, claiming social reforms in the 19th century Iran. The leaders of Baha’ism were persecuted by political and religious authorities during the rule of Qajar dynasty in the 19th century. Under the Pahlavi rule in the 20th century, the conditions of Baha’is were improved and they enjoyed freedom to practice their religion, open their temples, and hold government positions.72 Under the Islamic Republic, Baha’is are not recognized as a valid religious minority, rather they are seen as apostates and for that reason, cannot practice their religion openly.

Iran’s Christians are estimated to be around 280,000 Armenians and Assyrians who are concentrated in urban regions such as Tehran, Esfahan, Tabriz, Arak, and Orumiyeh. Iran’s Christians have not been mistreated; rather they have been well accepted as religious minorities by the Iranian Constitution under the Pahlavi rule as well in the Islamic Republic. Currently, they are permitted to choose their own representatives to the Parliament and can have their own schools and exert their own religious laws. In general, they have enjoyed a good standard of living and have contributed to the development of the Iranian society particularly through commerce, art, and industry. It is important to mention that while the Islamic Republic recognizes the Iranian Christians as a legitimate religious group, it does not tolerate evangelical services in Persian language and prevents Muslims from converting to Christianity.

It is interesting to note that Iran is home to the largest number of Jews anywhere in the Middle East outside Israel. The Iranian Jews are estimated at a community of 50,000 people concentrated in the Capital Tehran, and a few large cities such as Esfahan, Shiraz, and Hamadan. They date back to some 2000 years ago when the Achaemenid rulers liberated Jews from captivity.73 Over the course of centuries, the Iranian Jews have been merged with Iran’s mainstream society. They speak Persian as their mother language and have adopted the Iranian culture. Similar to Iran’s Christians, they have been accepted as a religious minority by the Islamic Republic Constitution and overall have enjoyed a good standard of living. Under the Islamic Republic, they are entitled to elect their representatives in the parliament, have their own cultural and educational centers, and exert their own laws regarding marriage and family issues. After the Islamic Revolution, many of Iranian Jews migrated to the United States or Israel. While the Jews enjoy the same degree of freedom as the Christians, they are regarded with some suspicion as they have family and business connections with Israel.

Table 1.2 The composition of ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups in Iran

|

Ethnic groups |

Religious groups |

Linguistic groups |

|

Persian (58%) |

Shia Islam (89%) |

Persian (58%) |

|

Azeri (24%) |

Sunni Islam (9%) |

Turkic (26%) |

|

Kurd (7%) |

Baha’ism |

Kurdish (9%) |

|

Arab (3%) |

Christianity |

Luri (2%) |

|

Lur (2%) |

Judaism |

Arabic (1%) |

|

Baluch (2%) |

Zoroastrianism |

|

|

Turkmen (2%) |

There are only about 32,000 Zoroastrians in Iran but Zoroastrianism occupies an important place in the Iranian society. Zoroastrianism is one of the oldest religions of the world and was practiced as the official state religion in Iran during the Sassanid Empire. After the conquest of Persia by Arab Muslims in the seventh century, the inhabitants of Iran converted from Zoroastrianism to Islam; nevertheless they preserved many Zoroastrian customs and traditions that are still present in Iran’s culture. Zoroastrianism consists of a monotheistic worship of Ahura Mazda (the Lord of Wisdom) and an ethical dualism opposing good and evil spirits. Many of the concepts of Zoroastrianism such as paradise, hell, devil, angels, the afterlife, and the last judgment are believed to have shaped Abrahamic religions including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.74 While Zoroastrians have not been subjected to harassment, they have suffered lower economic and social status and have migrated mainly to India in the 19th century. Under the Islamic Republic, the Zoroastrianism is accepted as an official religious minority whose followers are permitted to practice their religion freely, have their own cultural and educational centers, and exert their own laws with regard to marriage and family-related matters.