Structure and Components of Iran’s Economy

A Historical View

Between the1960s and the 1970s, Iran’s economy enjoyed growth rates of 10 percent per year along with growth in per capita income and low inflation.1 In the late 1970s, Iran was flourishing and had accumulated enormous amounts of surplus to invest. The 1979 Islamic Revolution suddenly disrupted the business activities, strained the existing social relations, and led to political and economic anarchy. Shortly after the revolution, the Islamic government nationalized large manufacturing and financial enterprises and the Revolutionary Islamic courts confiscated property of the so-called antirevolutionaries and capitalists.2 Banks and major industries like mining, transport, telecommunication, and utilities were forcefully nationalized. Very rapidly, the Islamic Revolution transformed the country into an Islamic state with a public sector dominating all economic sectors. With the Iran–Iraq War from 1980 to 1988, Iran faced sharp declines in oil production, high levels of inflation, and negative economic growth for more than eight years.3 After the war, the country embraced some timid economic reforms and tried to attract international investment. From March 1989 to March 1994, Iran followed the first five-year plan and undertook more liberal economic reforms that reduced state control.4 In the 1990s, the President Rafsanjani’s political and social reforms provided a more welcoming environment for business activities. As a result, the Islamic regime emphasized the security of capital and private property rights and gradually moved away from its revolutionary economic discourse.5 The second and third five-year plans continued until 2004 and advocated more ambitious economic programs and more privatization efforts.6 Between 1997 and 2005, President Khatami followed essentially the economic liberalization policies of his predecessor. Under Khatami the government launched extensive reforms such as tax policy changes, unification of the exchange rate, liberalization of imports and exports, and adoption of the regulations to attract investment. The election of Ahmadinejad in June 2005 and his reliance on a superficial populist discourse led to adoption of increasingly chaotic economic policies. Ahmadinejad had no clear economic agenda and represented one of the most reactionary factions of the Islamic Republic. Hence, his political and social policies resulted in rising internal stagnation and growing international pressure on Iran. Many of Ahmadinejad’s economic policies have been messy. For instance, his government continued Khatami’s reforms such as tariff reductions and privatization of state-owned enterprises, but increased the state control over the economy.7

An Overview of Iran’s Economy

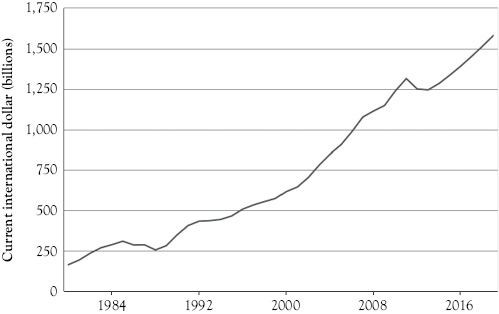

Iran was the 19th largest economy in the world in 1980, but with the Islamic Revolution and during war with Iraq, it suddenly fell to the 39th rank in 1994. According to the Central Intelligence Agency Factbook, the Iranian economy has risen again to the 19th largest in 2013.8 Despite small contractions in 1993 and 1994, the Iranian economy has been growing constantly since 1989 (after war with Iraq), with an average annual growth rate of 5.4 percent (See Figure 8.1 and Table 8.1). Especially in the past decades (1990–2010), Iran’s economy has been growing very rapidly with an average annual rate of 6.4 percent.9 A significant portion of this growth is attributed to energy sector and increases in oil revenues. For instance, between 1999 and 2006, the Iranian oil revenues tripled. In addition to energy, other sectors such as services, agriculture, and manufacturing have significantly contributed to the national economic growth. For the period from 2012 to 2017, Iran aims at keeping the annual economic growth around 6 percent, the inflation under 12 percent, and the employment under 7 percent. Furthermore, the country aims at reducing economic dependence on oil and gas, privatizing state-owned companies, and increasing the nation’s research budget to 3 percent of GDP.

Figure 8.1 Iran—gross domestic product based on PPP

Source : IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2014.

Table 8.1 Annual GDP growth based on PPP

|

Year |

Value ($) |

Change (%) |

|

2014 |

1,283.63 |

3.16 |

|

2013 |

1,244.33 |

−0.45 |

|

2012 |

1,250.01 |

−4.89 |

|

2011 |

1,314.24 |

6.09 |

|

2010 |

1,238.77 |

7.93 |

|

2009 |

1,147.73 |

3.06 |

|

2008 |

1,113.69 |

3.51 |

|

2007 |

1,075.93 |

9.20 |

|

2006 |

985.33 |

8.93 |

|

2005 |

904.54 |

6.61 |

|

2004 |

848.49 |

8.60 |

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2014.

In 2012, Iran’s GDP (calculated at purchasing power parity [PPP]) was estimated at $1.002 trillion. Due to harsh Western sanctions, in 2013 Iran’s GDP contracted between 1.5 to 1.9 percent and fell to $987.1 billion.10 The World Bank forecasted in its Global Economic Prospects report that Iran’s GDP will grow by 1.5 percent in 2014. According to the same report, growth rates of 2 percent and a 2.3 percent have been predicated for 2015 and 2016, respectively. Similarly, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has estimated growth rates of 1.3 percent and 1.98 percent in 2014 and 2015.11

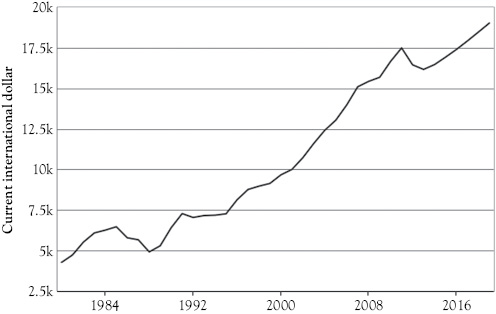

With its estimated $12,800 GDP per capita in 2013, Iran is classified as an upper middle income country (See Figure 8.2 and Table 8.2). In 2005, Iran was included in the Next Eleven emerging countries by Goldman Sachs Financial Group. According to this report, in addition to BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China), Iran is supposed to grow as one of the largest world economies by mid-century.12 Likewise, the IMF is optimistic about Iran’s long-term growth prospects. During the war with Iraq in the 1980s, Iran’s current account balance was in deficit, but since the mid-1990s, Iran has constantly run a current account surplus. Iran’s international reserves have been growing from $60.5 billion in 2006 to $81.7 billion in 2007 and $100 billion in 2008.13 Because of high reliance on oil revenues, Iran’s economy is highly exposed to periodical fluctuations in oil prices. To overcome these vulnerabilities, in 2001, the Iranian government created a special reserve fund to accumulate surplus oil revenues to smooth possible economic instabilities. The Reserve Fund has served the government to assert its political and military power, implement its expansionary monetary policies, finance construction projects, provide public subsidies, and even distribute cash among the poor. In a move to retaliate U.S. economic and political sanctions, the Iranian government has shifted its foreign reserves from American dollar to gold and other hard currencies such as euro and Japanese yen.14 Apart from a political move, the Iranian government believes that replacing dollar with Euro and other currencies is financially justified. After December 2007, Iran stopped accepting payments in the U.S. dollar and asked for other currencies for oil export purchases by foreign countries.

Figure 8.2 GDP per capita based on PPP

Table 8.2 GDP per capita based on PPP

|

Year |

Value ($) |

Change (%) |

|

2014 |

16,463 |

1.85 |

|

2013 |

16,165 |

−1.72 |

|

2012 |

16,447 |

−5.95 |

|

2011 |

17,488 |

4.95 |

|

2010 |

16,664 |

6.28 |

|

2009 |

15,679 |

1.62 |

|

2008 |

15,429 |

2.22 |

|

2007 |

15,095 |

8.00 |

|

2006 |

13,977 |

7.22 |

|

2005 |

13,036 |

5.00 |

|

2004 |

12,415 |

6.96 |

Inflation and Labor Market

As shown in Figure 8.3, the postrevolutionary Iran has experienced persistent high consumer price inflation for more than 30 years. Since 2000, the average annual inflation rate has been hovering around 15 percent. This high rate of inflation may be attributed mainly to the ineffectiveness of the government in pushing the Central Bank to constantly increase the money supply. Furthermore, the government has shown a tendency to provide cheap and easy credits to politically powerful borrowers such as the Revolutionary Foundations (bonyads), state-owned enterprises, and influential politicians.15 The interest rates for these borrowers are significantly below the market and in some cases are negative in real terms. To compensate for the difference between the real values of these loans and other expenditures, the government makes the Central Bank print more money and practically creates inflation. Other causes of inflation in Iran may be identified as the lack of government accountability, the government fiscal irresponsibility, corruption, lack of budget planning, and the expansionary fiscal policies. In all these cases, the government, via the Central Bank, fills the deficit with freshly supplied money. In the recent years (2009–2014), the Western sanctions have crippled Iran’s economy and have created additional inflationary pressures. For instance in 2013 and 2014, the annual inflation rate was hovering over 30 percent (See Figure 8.3, Table 8.3). The high inflation has led to lack of confidence in the national currency (rial) and pushed many Iranians to invest their savings in gold, real estate, and foreign hard currencies. More recently (2012–2014), spiraling prices have hit the population so badly that even the middle class families have been struggling with the mounting cost of food, housing, education, transport, and health care.

Figure 8.3 Consumer price inflation, annual percentage change

Source : IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2014.

Table 8.3 Consumer price inflation between 2004 and 2014

|

Year |

Value (%) |

Change (%) |

|

2014 |

19.8 |

−42.81 |

|

2013 |

34.7 |

13.77 |

|

2012 |

30.5 |

41.91 |

|

2011 |

21.5 |

73.81 |

|

2010 |

12.4 |

14.62 |

|

2009 |

10.8 |

−57.39 |

|

2008 |

25.3 |

37.26 |

|

2007 |

18.4 |

55.15 |

|

2006 |

11.9 |

14.90 |

|

2005 |

10.3 |

−32.30 |

|

2004 |

15.3 |

−2.07 |

In addition to hyperinflation, high unemployment rate is recognized as another obstacle to Iran’s economic prosperity. Indeed, some believe that unemployment remains the single largest hurdle to Iran’s economic growth.16 As shown in Figure 8.4 and Table 8.4, the economic growth has not kept pace with the population growth and as a result a large number of skilled or semiskilled workers have remained out of employment. It is estimated that each year, about 750,000 young Iranians enter the job market for the first time placing pressure on the government to create new jobs.17 The Statistical Center of Iran has announced that the average unemployment rate for the Iranian calendar year that ended on March 20, 2014 hit 10.4 percent,18 but some analysts believe that the real unemployment rate is much higher. The unofficial unemployment rates have been hovering over 15 percent in the past decade. Unemployment is considerably higher among the youth and excessively affects those under 30 years of age. In addition to unemployment, underemployment or working with high education or skill levels in low wage or skill jobs has become another major problem in the recent years. Due to rising educational and technical levels, a large number of Iranian youth cannot find the jobs that match their abilities and are forced to work in low skill and temporary employments. Under the increasing pressure of inflation and low wages, many workers may take up multiple jobs to make ends meet. The biggest employers are in the public sector including government, social services, education, agriculture, mining, trade, and transport areas. While the manufacturing sector employs almost 30 percent of the workforce, it makes a relatively small contribution to the gross national product.19 According to the Iranian Finance and Economic Affairs Minister, Iran must create 8.5 million new jobs in the next two years.20 Under these circumstances, many young and educated Iranians are forced to leave their home country in search of better professional opportunities. As reported by the IMF, Iran has one of the highest brain drain rates in the world.21

Figure 8.4 Unemployment rate

Source : IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2014.

Table 8.4 Unemployment rate between 2004–2014

|

Date |

Value (%) |

Change (%) |

|

2014 |

11.6 |

10.89 |

|

2013 |

10.4 |

−14.43 |

|

2012 |

12.2 |

−0.81 |

|

2011 |

12.3 |

−8.75 |

|

2010 |

13.5 |

13.15 |

|

2009 |

11.9 |

14.00 |

|

2008 |

10.4 |

−0.94 |

|

2007 |

10.5 |

−12.76 |

|

2006 |

12.1 |

−0.07 |

|

2005 |

12.1 |

17.48 |

|

2004 |

10.3 |

−8.85 |

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2014.

Economic Sectors

Industry is the largest sector and represents almost 45 percent of Iran’s GDP. It includes oil and gas, petrochemicals, steel, textile, and car manufacturing. The service sector and agriculture respectively account for 44 percent and 11 percent of Iran’s economy22. Despite its small size, the agriculture sector created 20 percent of jobs in 1991.23

Oil and Gas

With 10.3 percent of the world’s reserves of oil, Iran is placed in the third rank after Saudi Arabia and Canada.24 Furthermore, Iran has the world’s second largest gas reserves. Iran was the second largest producer of Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 2012 by an estimated production of four million barrels of crude oil per day. The main export markets for Iranian oil are Japan, China, India, and South Korea. Natural gas extraction is used for domestic needs and despite its immense reserves, Iran has very limited gas exports to the neighboring countries. Between 2002 and 2011, the country has greatly benefited from high oil prices and accumulated a sizeable hard currency surplus. However, the reliance on oil export revenues makes Iran’s economy highly vulnerable to the volatility of international oil prices. An unexpected decline of oil prices under $40 per barrel for an extended period of time may bring about serious financial implications.25 While natural resources in general and oil in particular contribute to wealth creation in a country, they can be detrimental to sustainable socioeconomic development as well. Many analysts believe that oil revenues have been responsible for deterring Iran’s industrial competitiveness. For instance, empirical studies show that countries rich in natural resources tend to have slower economic growth than countries with a smaller endowment of natural resources.26 The negative relationship between resource endowment and economic growth is particularly strong in countries with weak or corrupt institutions such as Iran.27 Oil contributes to about 60 percent of government revenues and 30 to 40 percent of GDP.28 As such, Iran’s government can be described as a rentier state that does not depend on domestic sources of production, but rather is the primary distributor of wealth in the society.29 Since the wealth creation is very largely independent of domestic production, the rentier state tends to violate the basic principle of efficiency in the society.30 This economic pattern may lead to empowerment of a small group of privileged politicians and their associates, prevalence of corruption, and lack of accountability to the population.31

Manufacturing Industries

Before and after the revolution, the government has tried to diversify economy by investing oil revenues in several industrial sectors. Iran’s manufacturing sector is more developed than those of other Middle Eastern countries; however, its share of GDP is still small relative to those of developing countries such as Brazil, China, India, and Mexico. In the recent years, industry sector has suffered due to increased exchange rates making the sector less competitive. Moreover, the Western imposed sanctions and three decades of political isolation have deprived Iranian industries from access to technological and managerial resources. Currently, Iran manufactures various products such as automobiles, telecommunications equipment, machinery, paper, rubber, steel, food products, wood, textiles, and pharmaceuticals. For instance, Iran is a main producer of steel in the world and the largest in the Middle East. Also, it produces different metals and nonmetal minerals such as coal, copper ore, lead, zinc, and aluminum. With two automotive giants (Iran Khodro and Saipa), Iran is the largest car maker in the Middle East and the 15th largest motor vehicle producer in the world.32 Car makers are hugely dependent on foreign technology. Some companies from France and Germany have a considerable presence in the Iranian automotive market. In the recent years, the Iranian car makers have initiated joint ventures with foreign companies including Peugeot and Citroen (France), Volkswagen (Germany), Nissan and Toyota (Japan), Kia Motors (South Korea), Proton (Malaysia), and Chery (China).33

Iran has hugely invested in petrochemicals. Currently, the country is the second largest producer of petrochemicals in the Middle East. It is estimated that the petrochemical industry needs an estimated $30 billion in fresh investment.34 Due to a large consumption market, in the recent years a growing number of medium sized companies have been involved in food products such as canned food, soft drink, meat processed food, fruit juices, and confectionary. These food-related products are consumed mainly in the domestic market; however, they have been marketed to other neighboring countries such as Iraq, Afghanistan, Persian Gulf States, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan. Some Western companies such as Nestlé and Coca Cola have signed contracts with local Iranian businesses.35

Service Sector

The service sector accounts for 44 percent of Iran’s GDP and includes a wide range of diverse activities in banking, financial services, education, and health care. Iranian financial sector is dominated by government intervention at all levels. Iran’s Central Bank or the Bank Markazi of Iran is under the direct control of the government and follows its fiscal and monetary policies. In 1979, shortly after the Islamic Revolution, the government nationalized all banks and took control over the financial sector. However, in the recent years there has been a growing trend toward privatization and liberalization of the economy.36 Consequently, some semiprivate banks have emerged in Iranian financial sector. These banks belong mainly to the Revolutionary Foundations (bonyads) and the state owned enterprises. In some cases, the shares of public banks have been sold on Tehran Stock Exchange. Nevertheless, a few state-owned banks control the financial sector. Some analysts have questioned the effectiveness of public banks in providing appropriate financial services.37 Moreover, private banks are restricted by complex and unstable regulations. In addition to the formal financial system, many individuals and small businesses rely on a complex network of trusted people to borrow, lend, and transfer money.

Agriculture Sector

The Islamic Republic has often emphasized the importance of agriculture as a means of economic and political self-sufficiency. Yet, in the recent years the weight of agriculture in Iran’s economy has decreased constantly. While agriculture represents only 11 percent of GDP,38 it is still the largest employer representing around 20 percent of all jobs in 1991.39 Agricultural output is relatively low, due to poor soil, lack of adequate water distribution, low quality seed, and undeveloped farming techniques. Iran is a net importer of grains, especially rice and wheat, and a net exporter of some well-known agricultural products such as caviar, pistachio, saffron, rice, wheat, barley, and a variety of fruits. The agriculture sector is threatened by droughts, climate change, environmental pollution, and lack of professional farmers. The country usually uses oil export revenues to pay for agricultural imports, but in the recent years a combination of factors including droughts, population increase, and rising international food prices have put strains on food security.40 Despite the emphasis of policy makers on agricultural sector, limitations of arable land and water practically prevent Iran from achieving complete food self-sufficiency.

International Trade

Despite the international sanctions, Iran’s international trade has been increasing over the course of the past decade. Thanks to higher oil revenues, from 2004 to 2007 the volume of Iran’s international trade doubled and reached $147 billion with a trade surplus of $36 billion in 2007. Nearly 80 percent of total export revenues result from oil and gas sectors.41 Petrochemicals, carpets, and dried fruits account for the rest of export revenues. Top export markets for Iranian oil are Japan, China, India, South Korea, and Italy. Top markets for nonoil exports are the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Iraq, China, Japan, and India.42 Because of limited domestic refinery capacity, the country is a major importer of gasoline. Iran’s gasoline imports were estimated around $5.7 billion in 2006 and $6.1 billion in 2007.43 Gasoline is subsidized by the government and is sold at a very low price, which leads to higher levels of fuel consumption. Major gasoline suppliers to Iran include India, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, the Netherlands, France, Singapore, and UAE. In addition to refined petroleum products, Iran imports a wide range of products such as industrial machinery, food products, and consumer goods. According to the IMF, in 2007 Iran’s top trading partners included China, Japan, Italy, South Korea, and Germany.44 As shown in Table 8.5, Germany, China, UAE, and South Korea are considered major suppliers of Iranian imports.

Table 8.5 Major trading partners, FY2007 (millions of U.S. dollars)

|

Country |

Total trade |

Exports |

Imports |

Trade balance |

|

China |

20,135 |

12,188 |

8,017 |

4,101 |

|

Japan |

13,064 |

11,599 |

1,465 |

10,134 |

|

South Korea |

8,421 |

5,139 |

3,282 |

1,857 |

|

Italy |

8,039 |

5,215 |

2,824 |

2,391 |

|

Turkey |

7,539 |

6,013 |

1,526 |

4,487 |

|

Germany |

6,066 |

621 |

5,445 |

−4,824 |

|

UAE |

5,915 |

747 |

5,168 |

−4,421 |

|

France |

5,334 |

3,069 |

2,265 |

804 |

|

Russia |

3,272 |

282 |

2,990 |

−2,708 |

Source : IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics.

As a result of tough economic sanctions, the U.S. trade with Iran is very limited and American companies are prohibited to invest in the country. This has provided golden opportunities for Japanese, Chinese, Russian, and European businesses. Many analysts believe that the United States sanctions against Iran are detrimental to American businesses and may deprive the United States of access to Iranian market.45 European countries and particularly Germany have been marinating strong economic and trade relations with Iran. However, it seems that more recently Iran has been shifting its trade from European countries to emerging economies such as China, Japan, Russia, Turkey, and Central Asian countries. Iran’s growing trade relationship with emerging countries is part of a reaction to political pressure from the Western countries. Furthermore, Iran has been seeking to use trade relations with countries like China and Russia to attract their political support on the international stage.46

As international sanctions have increased the difficulty of trade with Iran, UAE has become Iran’s most important connection to the global economy.47 Through this trade relationship, Iran overcomes the imposed international sanctions whereas UAE makes billions of dollars annually. Nonoil trade between UAE and Iran was officially estimated to be around $12 billion in 2007, but unofficial and often illicit trade volumes could be much bigger.48 The large part of this trade involves re-exportation or supplying Iran with repackaged foreign products from, Asia, Europe, and the Unites States. The U.S. trade with Iran is restricted, but many U.S. products are available in Iran via UAE.49 The trade relationship between the two countries is highly beneficial for UAE. For instance, in 2010, UAE exported over $9 billion worth of goods to Iran and imported only $1.12 billion worth of goods from Iran.50 One may suggest that after the Islamic revolution, Iran’s economic loss has been translated into UAE’s prosperity. On many occasions, the U.S. government has tried to put pressure on UAE to restrict its trade with Iran; however it seems that these attempts have not been effective in reducing the trade between the two neighboring countries.

Key Players in Iran’s Economy

According to Iran’s constitution, “The economy of the Islamic Republic of Iran consists of three sectors: state, cooperative, and private, and is to be based on systematic and sound planning” (Article 44, Iranian Constitution51). In practice, Iran’s economy is a mixture of central planning, state ownership of large enterprises, village agriculture, and small private firms.52 The state sector includes all large-scale and mother industries such as foreign trade, radio and television, telephone services and aviation. The private sector consists of small and medium-size companies concerned with products and services that supplement the economic activities of the state. The contribution of private sector is estimated at about 15 percent of GDP.53 The cooperative sector is practically insignificant and includes enterprises offering limited number of products and services. In addition, informal and other illegal activities constitute a considerable part of the Iranian economy. The Heritage Foundation has classified Iran’s economy as the 173rd freest in the 2014 report.54 In terms of economic freedom, Iran is ranked the last out of 15 countries in the Middle East and North Africa region and is known to have one of the closest economies in the world. The lack of economic freedom implies heavy state interference in many aspects of economic activity, lack of economic dynamism, and restrictive business and investment policies. In practice, the government controls economy through ownership and management of large state-owned companies, banks, Revolutionary Foundations (bonyads), and Islamic Revolutionary Guards.

Public Sector: State-Owned Companies, Bonyads, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The public sector consists of state-owned companies, bonyads, Islamic Revolutionary Foundations, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Shortly after the Islamic Revolution (1979), the State acquired ownership of large corporations in a variety of sectors including banking, insurance, telecommunication, energy, and transport. As a result of this rapid nationalization, the role of State in the Iranian economy was dramatically enhanced and all economic activities were run virtually by the government. Despite some timid liberalization efforts during Rafsanjani’s presidency in the 1990s, the state-owned companies remain the largest economic entities.55 Thanks to their significant influence, many of these large companies have received financial subsidies and business privileges from the government and have been protected from foreign and domestic competitors.56 This has resulted in low levels of productivity and efficiency in the state-owned companies particularly in industries such as automotive, steel, and transport.

Bonyads or Islamic Revolutionary Foundations were created in 1979 to manage the properties of the Royal family and their capitalist dependents. On the basis of Ayatollah Khomeini’s direct decree, the bonyads confiscated massive assets and suddenly became powerful semigovernmental organizations.57 The raison d’être of these foundations initially was to serve the poor and social justice, but later they relied on their revolutionary power and generous fiscal and economic privileges such as low interest rate loans, monopolies, government loopholes, and tax exemption advantages to conduct extremely lucrative business activities across the country. Currently, the bonyads are under direct control of the Supreme Leader and are not required to report their income and operations to the public. Furthermore, the bonyads are not subject to the Iranian legal or parliamentary supervision and are exempt from any taxes. It is often suggested that economic and political reform in Iran will not be effective unless bonyads come under the parliamentary supervision.58 The major problem with bonyads is that they intervene in all aspects of economic activity, compete with the private and state-owned enterprises, and are not accountable for what they receive from the public. Furthermore, it is very difficult to frame the bonyads, because they are obscure and complex foundations involved in a wide range of financial, social, charitable, religious, political, and cultural activities. Indeed, the exact magnitude of bonyads’ wealth and power is not known. The bonyads may have hundreds of companies in diverse industries. The largest bonyads include Bonyad Shahid va Isaar-Garaan (Foundation of the Martyrs and Veterans) with over 100 companies, Bonyad Mostazafan (Foundation of the Underprivileged), and Astan Quds Razavi (Imam Reza Shrine Foundation) with revenues of $12 billion in 2005.59 These bonyads are involved in both domestic and foreign economies in areas such as agriculture, construction, industries, mining, transportation, commerce, and tourism across Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.60

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is a military organization that was founded in 1979 to defend the new Islamic government and stifle any voice of opposition. The IRGC has emerged as a dominant power not only in defense and security matters but also in political and economic affairs.61 The IRGC consists of five branches: the Grounds Force, Air Force, Navy, Basij militia, and Qods Force special operations.62 After the war with Iraq, the IRGC crept into the Iranian economy through postwar reconstruction projects. Since then, the IRGC has benefited from the support of the Supreme Leader and has been involved in a variety of business opportunities like construction, oil, and gas projects.63 Very recently, the IRGC has started to acquire large state-owned enterprises and has become a major player in banking and telecommunication industries.64 Due to its control over Iran’s borders and airports, the IRGC, or at least some of its officials, are very likely to be involved in smuggling prohibited products into the country. Market participants are concerned about the presence of the IRGC in business activities and have complained about their exorbitant privileges and profits. Some analysts suggest that the harsh Western sanctions have provided a pretext for the IRGC to extend their grip over Iran’s economy.

Private Sector: Bazaaris, Industrialists, and

Small Businesses

After the Islamic Revolution, the private sector has shrunk dramatically as many businesses were seized by the new regime and their assets were transferred to the Revolutionary Foundations (bonyads). The existing private businesses consist of mainly Bazaaris and family-owned companies that operate in trade and distribution, agriculture, small manufacturing, and mining. Since Iran’s private companies have to compete with some powerful organizations such as the bonyads and the IRGC, they have small scale operations and limited prospects. Generally, it is possible to identify three major groups in the Iranian private sector: bazaaris, industrialists, and small and medium-sized businesses.

Bazaaris or urban traditional merchants work in the bazaar, which is a collection of shops and stalls in covered and open alleyways. According to Iranica Encyclopedia, the urban bazaar was and still is a social institution, comprising religious, commercial, political, and social elements.65 In addition to shopping area, the Iranian bazaar includes mosques, schools, restaurants, tea houses, gymnasiums, and bathhouses where merchants can meet and exchange information. The bazaaris represent mainly conservative and traditional groups of the society and institutionally have close ties with the clergy and religious leadership.66 After the Shah’s White Revolution in the 1960s and the subsequent modernization of Iranian society, the economic weight of bazaaris diminished substantially. The resentful bazaaris opposed the Shah overwhelmingly and played a critical role in the Islamic Revolution by promoting and financing strikes and public demonstrations.67 The bazaaris are engaged in a wide range of business activities such as importing, exporting, wholesaling, retailing, and lending money. Since Iran is a society of trade merchants with limited manufacturing sectors, the bazaaris have an important economic function.68 They maintain a strong hold on Iranian economy and politics, and in order to protect their own interests, resist economic and social openness, foreign direct investment, and international competition.69 Over the course of the past 50 years, the rapid economic modernization has reduced the traditional importance of the bazaar, but has not led to its demise. More recently, the bazaar merchants are becoming specialized in certain products such as carpets, jewelries, gold, and food products and are supplementing modern shopping areas.

The industrialists represent more educated or modernized entrepreneurs than bazaaris and are marked by their liberal socioeconomic values. They are involved mainly in manufacturing and technological sectors, which are not under the control of bazaaris or the government. The small and medium-sized businesses are owned and run mostly by the middle class individuals. They have limited financial, technological, and managerial resources and struggle to make a living. As a result, they cannot usually grow at the national and international levels.

Future Outlook

The Western and American economic sanctions have resulted in multiple and sometimes conflicting outcomes. On the one hand, the sanctions have created substantial barriers to doing business with Iran, have complicated its business environment, and have led to low levels of foreign investment. As a result, Iran has experienced significant difficulties in developing its oil and gas sectors.70 On the other hand, the sanctions have generated golden opportunities for American rivals predominantly China and Russia in expanding and deepening their trade, business, and political ties with Iran.71 Likewise, the Western sanctions have diverted Iran’s trade and business from the Western countries to the emerging and Eastern countries such as India, Brazil, China, South Africa, South Korea, and Malaysia. Meanwhile, Iran has been able to circumvent the sanctions by transshipment from neighboring countries like UAE and Turkey.

It seems that there is no political will and social capacity to transform the country’s rentier economy at least in the near future.72 Therefore, Iran’s economic growth remains highly dependent on the energy sector in short and mid-terms. Despite the government’s attempts to diversify economy, oil and gas revenues still account for almost 80 percent of the total export revenues. Iran’s oil and gas sector has huge growth potential and one may suggest that energy prices and the ability of Iran in developing and exporting its oil and gas resources will be central to its economic prosperity in the short term. In the past decade between 2004 and 2014, Iran enjoyed a high economic growth, but the prospect of such growth remains uncertain. If the country can overcome geopolitical and international risks, the overall economic growth seems quite positive.73 Any sharp decline in oil prices below $90 per barrel may create serious challenges to the country’s economic growth. In addition to international sanctions and energy prices, Iran’s economy is highly affected by internal factors including domestic policies, stability, economic planning, and management or mismanagement of country’s resources. The last eight years from 2005 to 2013 have been marked by economic mismanagement, high unemployment, hyperinflation, brain drain, and rising corruption at all levels. It is crucial for the government to take some macroeconomic measures to reduce inflation, increase non-oil output, and minimize the government fiscal dependency on oil revenues.74 Some have a positive assessment of Iran’s economy and believe that the nation’s economic performance is satisfactory. However, many others argue that given the abundant natural resources and endowments, Iran’s economy has been constantly underperforming after the Islamic revolution.