Chapter 5

The Withdrawal Source Section of the Spreadsheet

Bob spent some time overnight thinking about Jane and June’s questions and comments on the previous day’s session. Since Jane had said she was less comfortable with the lower part of the result page than the top part, Bob took some more pains with this part.

So, he opens up his computer and reloads the data from the previous day, switches to the “Assumptions” tab, and points to the withdrawal source section of the spreadsheet. (See Figure 5.1.)

Cash Delta

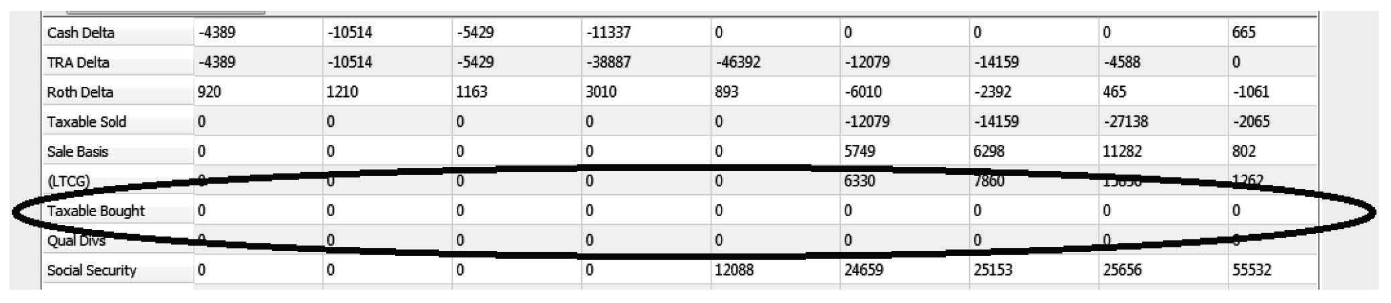

“Let’s start with the first row in that area, ‘Cash Delta.’” (See Figure 5.2.)

Bob continues, “‘Delta’ is a math term meaning ‘change in something.’ In this case, ‘Cash Delta’ means ‘change in your cash holdings.’ So, if we look at the entry for ‘Cash’ at the beginning of a year, then add the ‘Cash Delta’ entry for that year, we should get almost the ‘Cash’ entry for the beginning of the next year. For instance, if we add the ‘Cash’ entry for 2017, which is $30,000, to the ‘Cash Delta’ for that same year, which is -$4,389, we get $25,611. The ‘Cash’ entry for 2018 is $26,210, which is $599 more. Where did that $599 come from? June?” (See Figure 5.3.)

June says, “Well, that’s almost $600, which is 2% of the starting amount in 2017. I see that the ‘Assumptions’ tab shows 2.0% as the ‘Cash Nominal Return.’ Is that how it is calculated? And if so, why isn’t it exactly $600?”

Bob replies, “Go to the head of the class! Yes, the difference is the interest. As to why it isn’t exactly $600, that’s because the program is optimized for speed rather than accounting exactness. If it were a tax-preparation program, it would have to do all the arithmetic precisely, but that is much more complex and slower even on today’s very fast machines.”

Why it’s Not Important to Calculate Future Results Precisely

“Now of course it seems as though it would be better to get perfectly correct answers than taking shortcuts like this. But in fact, there are no perfectly correct answers anyway. Even if we can assume that we are getting exactly 2% on cash, we don’t know exactly what the return on our other assets is going to be, nor do we know what the tax brackets will be for any year that isn’t over yet. In fact, it would be a miracle if the first two digits of the ‘Yearly Spending’ number were correct, so a few dollars here or there make no difference in the accuracy of a projection of this type. Does that make sense?”

June replies, “I think so. Whatever projection the program makes isn’t going to come out exactly right anyway, because it depends on data that we won’t have until after the fact. So, the fact that the arithmetic isn’t exact doesn’t matter. Is that right?”

Traditional Retirement Account Delta

Bob answers, “Yes, that’s exactly it. OK, now let’s move on to the next row, ‘TRA Delta.’ Jane, what should that represent?” (See Figure 5.4.)

June replies, “That should be how much we should take out of the ‘Traditional Retirement Accounts,’ right?”

Bob says, “Right.”

Jane continues, “I see that in this case we start taking money out of that account right away. Is that because we get a higher ‘Yearly Spending’ level by using that money first and preserving the taxable account balance?” (See Figure 5.5.)

Bob replies, “Yes, the program has projected that ‘Cash & TRA’ looks like the best withdrawal method in your particular case, given our assumptions. So, in this case, you would hang on to the taxable account until you have used up most of the cash and traditional retirement accounts.”

Roth Delta

“Let’s continue with the ‘Roth Delta’ row.” (See Figure 5.6.)

Jane says, “We discussed this a bit yesterday. I know it starts out as 0 because we don’t have a Roth account set up yet. The deposits starting in 2017 are from ‘extra money’ that we get from Jim’s salary, right? It doesn’t seem like we ever have any ‘extra money’ that isn’t accounted for, but I guess that’s fairly normal.”

Bob answers, “Yes, I’m afraid that is normal. However, if you want to have about the same ‘real’ spending level (that is, after tax and inflation) for the rest of your life, you must save money while you have more income, so that you will have it to spend later. This is just a special case of that general rule.”

June interjects, “Is that how the program works? It tries to level spending out for the rest of the couple’s life?”

Bob replies, “Yes, that is the idea, aside from the ‘Expected Additional Expenses,’ it looks for the maximum level after-tax, inflation-adjusted cash flow if one spouse dies at the worst possible time. Wow, that’s a mouthful!”

June says, “Can you give us an idea of how it does that? We don’t need every step, but just the general approach? Assuming you know, of course.”

Bob answers, “Yes, the ‘theory of operation’ is covered in the documentation that I studied to be able to use the program effectively, so I should be able to explain that. But I’d rather finish the explanation of the withdrawal source section of the spreadsheet first, if you don’t mind.”

They nod in agreement, so he continues with the next row, “Taxable Sold.” (See Figure 5.7.)

Bob continues, “The ‘Taxable Sold’ row shows the amount of assets sold from Jane and Jim’s taxable account. As you can see, the program shows no sales from that account until 2022, as it has you selling off your TRA assets to preserve your taxable account balance as long as possible. In your particular case, selling TRA assets and drawing down your cash turns out to be the approach that gets the highest after-tax cash flow (as always, if the assumptions turn out to be correct). Any questions on this row?”

They both shake their heads.

Sale Basis

Bob continues, “The next row, ‘Sale Basis,’ usually inspires some questions. Let me explain it first, though.” (See Figure 5.8.)

Bob goes on, “What that row shows is how much you paid for the assets in your taxable account that were sold in the ‘Taxable Sold’ entry for the same year. Let’s look at the entries for the ‘Taxable Sold’ and the ‘Sale basis’ rows in 2022.” (See Figure 5.9.)

“In 2022 you would be selling $12,079 worth of assets from your taxable account, as shown in the ‘Taxable Sold’ cell for that year. What you paid for that $12,079 worth of assets is $5,749. Any questions so far?”

Jane says, “Yes, two. First, where did that $5,749 amount come from? Second, why does it matter how much we paid for the assets we are selling?”

Bob replies, “The $5,749 is calculated from the ‘Taxable’ and ‘Tax Basis’ entries in the ‘Assets’ tab, the $12,079 sale amount, and the 7% ‘Portfolio Assets Nominal Return’ assumption.” (See Figures 5.10 and 5.11.)

Bob continues, “First we multiply the year 2022 starting taxable account value of $98,178 by 1.07 (adding 7% return), so at the end of 2017, that taxable account should be worth $105,050. Then if you are selling $12,079 out of $105,050, that is (let me get out my calculator) … a bit less than 11.5% of your taxable assets. So, we take 11.5% of your ‘Tax Basis’ of $50,000, which is $5,750. The actual number on the spreadsheet is $5,749, which is a bit less than $5,750, so it looks as though our calculation is right. Does that answer your first question?”

Jane replies, “Yes.”

Bob then continues, “Now, as for why this matters, it affects your taxes.”

Long Term Capital Gains

“See the next row, labeled ‘(LTCG)’?” (See Figure 5.12.)

Jane nods her head.

Bob continues, “LTCG stands for ‘long term capital gains.’15 This is a special type of income that has better tax treatment than many other types of income. The maximum tax rate for such gains is 20% unless you have a lot of taxable income, much more than you and Jim have. In fact, you can pay as little as 0% tax on capital gains if your other income is low enough. It is calculated on the amount you get for selling assets (‘proceeds’) minus the amount you paid for those same assets (‘cost basis’). So we need to know the cost basis of the assets being sold. That’s what the ‘Sale Basis’ row represents.”

“Of course, these rules are subject to change at any time by Congress, but since no one knows what the tax laws will be in the future, all we (or anyone else) can do is use current law for our projections.

“Do you have any questions on this row?”

Jane answers, “I understand that capital gains taxes apply only when we sell. If so, we can time the sales to reduce taxes, right?”

Bob replies, “Yes, that is possible. The problem if you have mutual funds is that you can’t control when they sell, which can also cause you to incur a tax liability. If you have individual stocks or other assets that aren’t part of a mutual fund, you can generally decide when to sell. There are exceptions to that rule too, but they don’t apply in most cases.”16

“Any other questions on this row?”

Both sisters shake their heads.

Taxable Bought

Bob continues, “The next row, ‘Taxable Bought,’ is basically reserved for future use, since the current version of the program doesn’t ever buy assets in the taxable account.” (See Figure 5.13.)

Bob continues, “Instead, as we’ve already seen, if there is extra income, it buys Roth assets to the extent that is feasible based on tax law. Any questions on this?”

Both sisters indicate that they are satisfied.

Qualified Dividends

Bob continues, “The next row is used if you have reported any ‘qualified dividends’ on the ‘Income’ tab.” (See Figure 5.14.)

“However, since you don’t have any such dividends, this row will be filled with zeroes. Any questions on this?”

Jane says, “What makes a dividend ‘qualified,’ and why is that important?”

Bob replies, “It depends on the company meeting certain qualifications in the tax law. If you get a dividend reporting tax form from the company, it should say on the form whether the dividend is qualified. It’s important because qualified dividends get capital gains tax treatment (very favorable) rather than ordinary income tax treatment (unfavorable). Any other questions?”

The sisters shake their heads.

Social Security

Bob continues with the explanation of the next row, “Social Security.” (See Figure 5.15.)

Bob continues, “As you can see, this assumes that you start taking Social Security in June 2021, which is why the amount for that year is only $12,088. Do you remember how that date was chosen?”

Jane replies, “I recall that you clicked the ‘Optimize SS Dates’ button after we put in the return assumptions. Is that right?”

Bob says, “Yes, that’s right.”

Taxable Income

“The next row is ‘Taxable Income’.” (See Figure 5.16.)

Bob continues, “In your case the entries on this row are just Jim’s salary until his planned retirement in 2021, after deducting the FICA tax but before income taxes, amounting to $46,175 a year. Do you have any questions on that?” (See Figure 5.17.)

Jane answers, “Yes, I do have a couple of questions. Why is FICA deducted but not income taxes? And what else could go on that Taxable Income row, even if it doesn’t apply to us right now?”

Bob replies, “Well, for your first question, that’s because FICA taxes are a flat percentage that can be calculated just from your salary income, so the program can just display ‘salary after FICA’ as a fixed number that can be used toward your spending allotment. On the other hand, income taxes on your salary depend on your other income, which depends in turn on how much we are selling from your taxable accounts or withdrawing from your retirement accounts. Thus, the program has to estimate income taxes after figuring out both of those numbers. Does that make sense now?”

Jane nods her head, so Bob continues, “Now for your second question, if you had an annuity, then some of the money that you get from it is considered taxable income and some is considered nontaxable, because it represents the return of part of the premium you paid for the annuity.”

Nontaxable Income

Jane says, “Is that what the next row, ‘Nontaxable Income,’ is for?” (See Figure 5.18.)

Bob says, “Yes, that’s right. The nontaxable part of any annuity payments goes there, but so far, anyway, you don’t have any annuities, so all of the numbers are 0.”

“That finishes off the ‘withdrawal source section’ of the spreadsheet. I’m sure you will also want to go over the last section, the ‘cash, taxes, and insurance premiums’ section, since that’s where the ‘rubber meets the road.’ But I think we’ve done enough for today. How about if we continue tomorrow at 1 PM?”

Jane and June both nod, so Bob shuts down the program and closes up his laptop.