1. Developing Supply Chain Strategies

1.1.1 Logistics, Supply Chains, and Supply Chain Management

1.1.2 Types of Organizational Planning: Strategic, Tactical, and Operational Planning

1.1.3 Elements of Organizational Strategic Planning

1.2 Supply Chain Strategic Planning

1.2.2 Supply Chain Strategy Opportunities

1.3 Critical Success Factors in Developing a Supply Chain Strategy

1.5 A Procedure for Supply Chain Strategy Development

1.6 Starting Place for Strategy Development: Customer Value

Terms

Aggregate planning

Critical success factors (CSFs)

External environmental analysis

Internal organizational analysis

Introduction stage, life cycle

Push-pull strategy

Third-party logistics (3PL)

1.1. Prerequisite Material

In this chapter and select chapters that follow, an introductory “Prerequisite Material” section seeks to acquaint less-experienced students of supply chain management with basic and elemental content and terminology. Experienced supply chain executives and managers might be tempted to skip this section in chapters where it is included, but they might instead want to use it as a review of basic concepts and terminology.

1.1.1. Logistics, Supply Chains, and Supply Chain Management

Logistics refers to the movement of things (that is, people, material, parts, finished goods, and information) in appropriate quantities and timing to meet the needs of an organization’s stakeholders (that is, both internal stakeholders, like employees, and external stakeholders, like suppliers and customers). Logistic management seeks to manage the flow of manufactured products, services, and information through a business operation to the final customer. Complemented by logistics and logistics management, a supply chain represents a network of all processes, elements, and relationships that moves information, services, and materials, from their origins (for example, unearthed raw materials, supplier parts) through internal production in manufacturing organizations, delivery in service organizations, or external outsourcing vendors or supply partners for distribution networks to eventual consumers and beyond. As presented in Figure 1.1, a supply chain consists of a network of connected, independent suppliers, manufacturers/service organizations (usually many), distribution centers, retailers, and customers, which are all represented as nodes in the supply chain network. Some supply chains are less inclusive and are not concerned with upstream, multiple-tiered suppliers provide raw materials, downstream distributors, or retailers that market the product (for example, a commercial customer who receives goods directly from a manufacturer). Most firms today include a component of sustainability (that is, the desire to conserve resources and do no harm to the environment) in operations. (Chapter 6, “Sustainable Supply Chains,” discusses sustainability in more detail.)

Figure 1.1. Simple supply chain network and flow diagram

Source: Adapted from Figure 5.1 in Schniederjans and Olson (1999), p. 70.

Generally, supply chains are divided into upstream (that is, various multiple levels of supplier tiers) and downstream (that is, finished product or service distribution and customers). Also, the flow of products travels downstream from suppliers to customers, while information about an organization’s performance and customers tends to travel upstream through the supply chain.

Whereas logistics management provides a planning framework for supply chains, supply chain management builds linkages with various independent supply chain participants (for example, suppliers and customers). It is a management process that involves establishing and building trusting relationships. Indeed, supply chain managers seek to establish a relationship that is more of a partnership than just a transactional relationship involving the purchase of items from suppliers or the selling of items to customers. Supply chain managers working closely with their supply chain partners seek to deliver greater value to customers by reducing costs throughout the supply for all partners. Working with partners, supply chain managers seek many value enhancing objectives, but to do so requires planning.

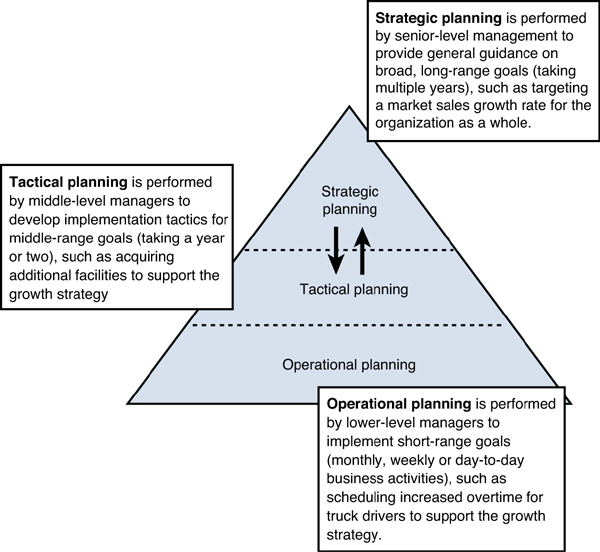

1.1.2. Types of Organizational Planning: Strategic, Tactical, and Operational Planning

An overview of the typical organizational planning process is presented in Figure 1.2. Strategic planning usually involves issues that may significantly impact the organization from the external environment (for example, customers and competitors). It deals with issues such as what the firm wants to do in the future (for example, what industries or markets to explore), what businesses the firm wants to be in, and how to allocate the firm’s total resources. Strategic planning also involves self-examination to determine resources and strives to move the organization toward longer-range strategic goals (for example, corporation growth in market share). The president of the firm and the board of directors usually undertake this planning. The outcome of this effort is a clear statement of long-term (for example, perhaps three or more years in the future) goals.

Figure 1.2. Organization planning stages

Source: Adapted from Figure 1.3 in Schniederjans et al., (2005), p. 37.

Tactical planning is the next step down from strategic planning efforts and deals with developing implementation approaches to achieve the strategic longer-range goals. It is the stage in the organizational planning process that breaks down longer-range goals into more immediate goals with greater detail. For example, in an organization where market share is a strategic goal, a tactic that would support this strategic goal might be to acquire a competitor in the next year or two to grow through acquisition. If a strategic goal is to become the most environmentally friendly organization in an industry, one supportive tactical goal might be to invest in or build a recycling facility in the next year or two. Chief operating officers, vice presidents, and general managers representing functional areas (for example, operations, finance, marketing) or divisions in an organization planning usually undertake this planning effort. The outcome of this planning effort is a set of intermediate goals that guide each of the functional areas or divisions over the next one or two years. These are more specific goals that take place within a fairly defined time horizon (for example, completing a building or a new production facility by a fixed date).

Operational planning is the final step in the organizational planning process that breaks down tactical goals into very detailed short-range goals for areas, groups, and individuals who make up the firm. All types of lower-level managers or supervisors throughout the organization undertake this planning effort. These short-range goals are very specific. Examples of operational plans include scheduling monthly, weekly, or daily production assignments for employees; arranging transportation scheduling for shipments to specific customers; and setting up purchasing order systems for parts.

1.1.3. Elements of Organizational Strategic Planning

Organizational strategic planning is a fairly common and consistent process undertaken more frequently when substantial change in an industry warrants reexamination of the direction a firm is strategically taking. The overall process of organizational strategic planning usually begins by reviewing a firm’s mission statement (that is, a document defining broad objectives, like making profit) (see Figure 1.3). This is done to ensure the firm’s strategic goals align with what it espouses in its mission statement.

Figure 1.3. Organization planning stages

Source: Adapted from Figure 2.2 in Schniederjans (1998), p. 22.

The external environmental analysis examines the environment external to the organization (for example, competitor actions, new technology). This analysis seeks to determine possible risks and opportunities (for example, mergers and acquisitions, new supply chain partners) that might offer the acquiring firm an improved competitive position. This analysis helps provide answers to questions such as whether we are at risk from new competitors. If the opportunities are not greater than the risks, the analysis comes to an end and the firm does not pursue any changes in strategic plans. If the opportunities look more promising than the risks, an internal organizational analysis is undertaken.

An internal organizational analysis looks internally to identify strengths and weaknesses the organization may have in pursuing business plans. This analysis seeks to answer questions such as whether the organization has the finances, staff, and facilities to undertake opportunities identified in the external environmental analysis. If the answer is no, either the firm finds the resources it will need, or it does not take advantage of the opportunities. If the answer is yes, the firm initiates additional planning to define goals and align the organization’s resources to achieve them.

The desired end result of these two analyses is a set of strategic goals that an organization can use to guide planning efforts. As shown in Figure 1.3, the organizational strategic goals can be broken down into tactical goals in functional areas such as operations/supply chain. Actually, the operations/supply chain executives (for example, vice presidents, general managers) usually develop function-level strategies that serve to guide tactical efforts. So, it is accurate to say that at each of the three planning levels (strategic, tactical, operational) strategies, tactics, and operational plans can be developed by organizational members to further detail and guide the organization to achieve its objectives.

Other possible outcomes of the organizational strategic planning process include the identification of critical success factors and core competencies. CSFs are a “must-have” set of criteria identified as critical for conducting business. They may be human, technical, financial, or resource, without which a firm believes it cannot be successful. CSFs are often identified during the internal organizational analysis, where organizational strengths are found. A related concept to CSFs is core competency. A core competency is what the firm can do better than its competitors. A core competency can be a CSF. An example of a core competency is the supply chain network that is more efficient than its competitors. Core competencies are often found during the internal organizational analysis where strengths are identified. Firms build on core competencies and try to outsource or improve noncore competencies.

1.2. Supply Chain Strategic Planning

“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

—Lewis Carroll

1.2.1. Positioning for Strategy Development: Understanding the Life Cycle of Products in Supply Chains

For an entrepreneur starting a new company with a single product or for seasoned supply chain executives with the responsibility of managing the flow of thousands of products, there will always be a need to plan for supply chains and develop strategies to develop, maintain, and end them. Where should a planner begin to develop a strategy for the supply chain? The answer depends partly on where the manager’s product is located in its life cycle of its supply chain.

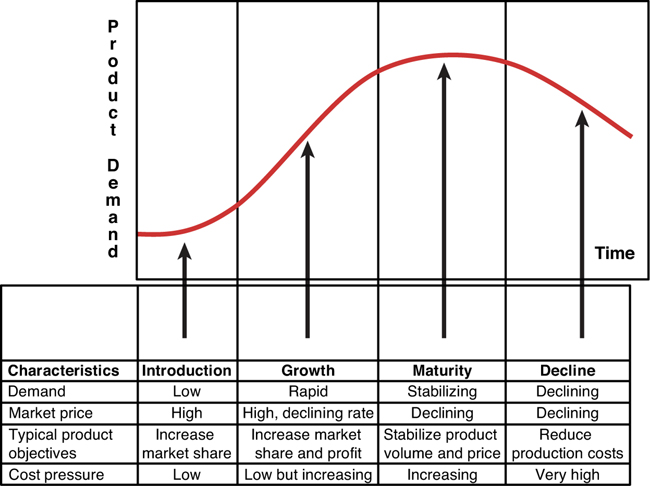

A product life cycle entails a single product’s unit demand divided into four stages: introduction, growth, maturity, or decline based on customer demand (as shown in Figure 1.4). The introduction stage is where a product is introduced. Demand increases at a slow rate, while the product gains acceptance in the market. The growth stage is characterized by product demand that increases at an increasing rate. The maturity stage is where product demand peaks and flattens out. The decline stage is where product demand increasingly decreases.

Figure 1.4. Product life cycle planning stages

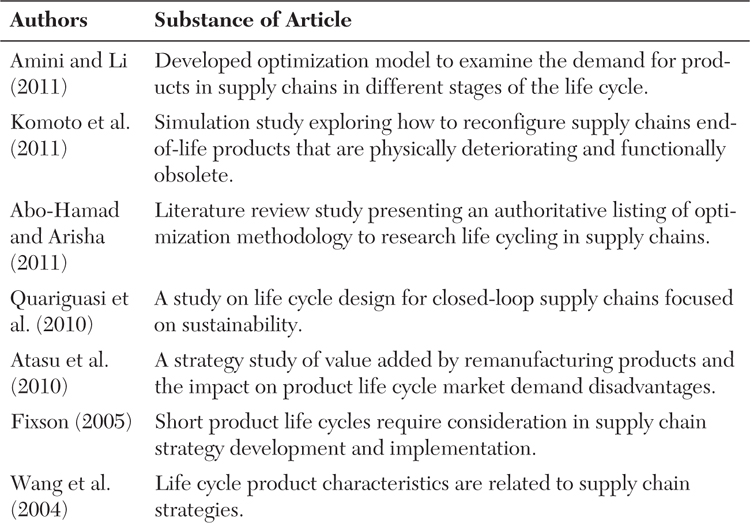

The use of the product life cycle to plan a single product’s supply chain is well documented in the literature (see Table 1.1) and continues to be a valid planning tool (as discussed throughout the remaining chapters).

Table 1.1. Select Research on Product Life Cycle and Supply Chains

How can the position on the product life cycle be determined? Most experienced supply chain managers can answer this question by following demand forecasts. Today, statistical software not only forecasts demand but also projects trends that reveal life cycle stage behavior for individual products and product lines.

Once a product life cycle stage position is known, managers can use that information to better plan supply chain strategy within each stage of the life cycle. The life cycle position can help prepare managers for eventual changes that move a firm’s supply chain planning efforts forward or backward in the life cycle by adapting or aligning strategies to fit the current market demand situation. The continual alignment or realignment of a supply chain is essential to be competitive. The supply chain activities used to create, maintain, and end a supply chain (or individual supply chains within a larger network) represent the supply chain life cycle. Managing the supply chain life cycle mirrors product life cycles. Like a product life cycle, the same strategies used in managing a supply chain life cycle are not as successful in differing stages because customer (and partner) needs change. Although many experienced supply chain executives can “feel the pulse” of demand within supply chains, it is better to know in advance using a life cycle approach of the direction and rate of change taking place or trending, to better lead supply chain planning for a product or a collection of products during each stage of a life cycle.

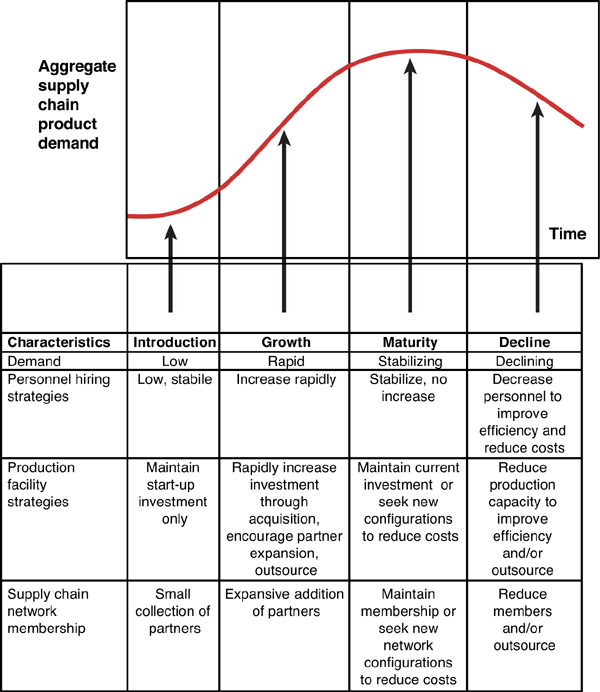

There are complicating factors to managing individual product life cycles in a supply chain network. For example, the aggregation of a product line or group of products produced and shipped through a supply chain network adds considerable effort to planning (see Figure 1.5). These products may have differing product life cycle timing and demand requirements but require an aggregated supply chain plan. Illustrated in Figure 1.6, the aggregated demand of a product line or group of products can create an aggregate product life cycle. When carried over the life of a firm, this figure represents the life cycle of both the firm and the supply chain. The impact of aggregation may also require a substantially different level (aggregated) of planning.

Figure 1.5. Relationship of product life cycles and their aggregation

Figure 1.6. Aggregate life cycle supply chain planning

In Figure 1.7, the characteristics of this level of planning are considerably broader or more strategic in nature than the usual single product planning effort.

Figure 1.7. Procedure leading to the development of supply chain strategies

Throughout this book, references made to the product life cycle are used to illustrate how some global aspects of supply chain life cycles can be dealt with by managing product life cycle issues. It is the application of product life cycle strategies and methods that can help reinvent and revitalize a firm’s supply chain life cycle.

1.2.2. Supply Chain Strategy Opportunities

Typical supply chain strategies might include building new supply chain networks to better serve customers or establishing recruiting programs to bring appropriate talent to a firm over an extend period of time. There are many possibilities for strategic objectives to be established and achieved. The key in strategic planning is to make sure the plan is aligned with the abilities of the firm and aligned to serve customers.

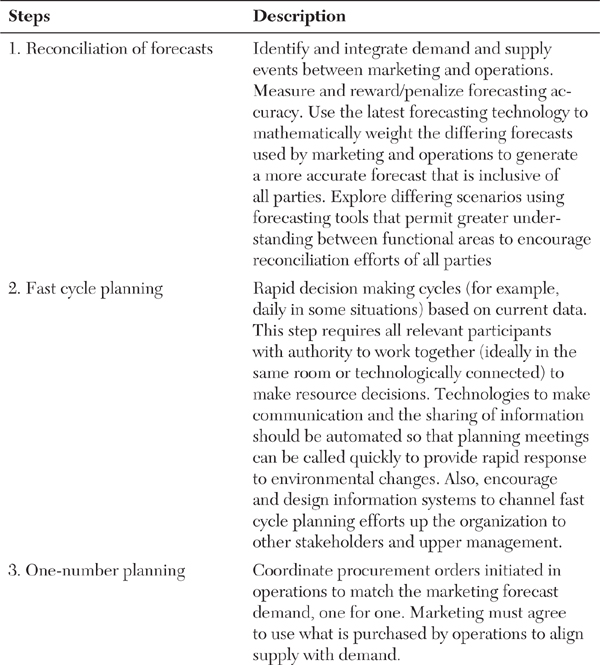

One approach for aligning a firm’s strategies is through consensus planning. Consensus planning refers to a process where conflicting, functional organizational objectives and knowledge are intelligently reconciled to benefit all (McBeath, 2011). The steps in consensus planning are presented in Table 1.2. The steps in Table 1.2 seek to bring empowered decision makers together, motivating them to share forecasting information and weigh value with accuracy as a goal to reconcile functional differences. In doing so, it helps to align marketing with operations. It also reflects that planning efforts have very different timing requirements. Fast cycle planning compresses supply chain decision cycles so that rapid decision making can be initiated to avoid supply chain problems (like the bullwhip effect often caused by inaccurate forecasting resulting in excessive operational waste). Strategic planning is considered long-term planning, but for some organizations that time period could be months, not years. Likewise, tactical planning might be days instead of months, and operational planning could be minutes and not days.

Table 1.2. Consensus Planning Steps

Source: Adapted from McBreath (2011).

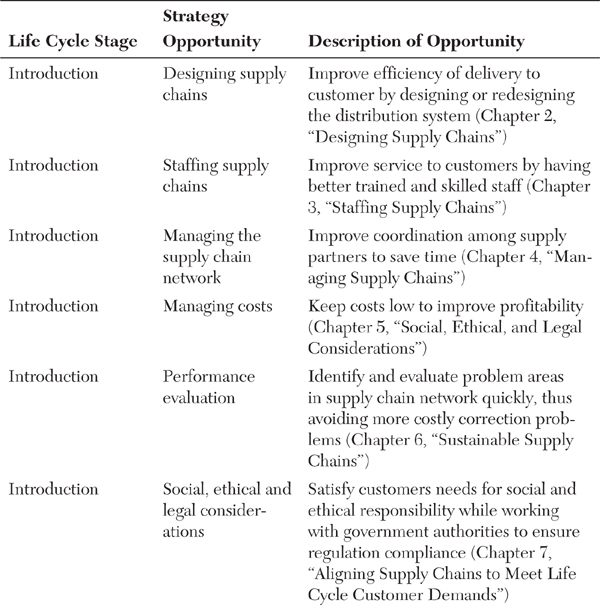

Within each of the life cycle stages, many opportunities exist to develop strategies to overcome problems, improve efficiency, and achieve supply chain excellence for customers. The strategy generalities presented in this chapter are a good starting point, but considerably more detail is needed to understand the diversity of strategic issues that supply chain managers’ face. The opportunities for strategic planning and decision making are as varied as the multitude of tasks supply chain managers are asked to perform. The content of this book focuses on many topical areas that require strategy development. In Table 1.3, supply chain strategy opportunities are briefly listed as they relate to the content and chapter locations within this book. You can use this table as a quick literature reference guide to specific content areas of study in supply chain planning.

Table 1.3. Supply Chain Strategy Opportunities

1.3. Critical Success Factors in Developing a Supply Chain Strategy

Every supply chain is unique, and the strategies needed for business success in one supply chain can be completely different in another. To deal with this diversity of application, criteria can be established to guide managers to identify areas within unique supply chains where strategic planning can be used to benefit the organization.

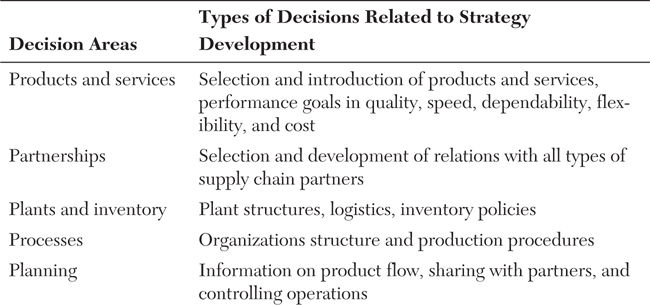

One approach to supply chain strategy development is to utilize CSF criteria in supply chains. CSFs can be used to identify relevant supply chain issues that would benefit from strategic planning efforts. One set of criteria was suggested by Slone et al. (2010). Although structured as steps in a proposed strategy development process (see Table 1.4), this set of criteria offers CFSs in the development of supply chain strategies. Any one of the five criteria could and should be used to develop strategies in an effort to continually enhance supply chain performance.

Table 1.4. Supply Chain Strategy Development Steps

Source: Adapted from Slone et al. (2010), pp. 40–51.

Relating the five CSFs back to the concept of a product life cycle, note that any of these five can be used at any life cycle stage. For example, consider the CSF of “selecting leaders and developing supply chain talent” from Table 1.3. Some executives are more efficient and successful at managing supply chains in growth stages, whereas others are more successful managing during the maturing stages. Optimizing a supply chain requires realigning talent to the life cycle stage of the supply chain. Alternatively, it requires executives be cognizant of the life cycle stage and to adapt its needs to the supply chain that supports it.

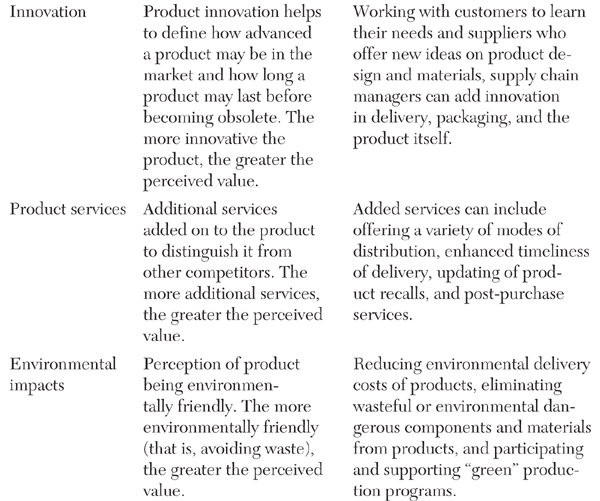

Another view of supply chain strategy CSFs is presented in Seuring (2009). In this research study, the author suggests strategy development in supply chains is a function of five criteria (see Table 1.5). These criteria are based on the types of decision areas that a typical supply chain manager has to deal with in the course of running the network. Other researchers advocate a similar listing of criteria for supply chain strategy development, such as product innovation, price and brand, value-added services, and relationships and experiences (Simchi-Levi, 2009, pp. 19–31). Whatever guiding paradigm a supply chain executive or manager chooses to use, CSFs can help identify areas for strategic planning and focus planning efforts.

Table 1.5. Supply Chain Strategic Decision Making Criteria

Source: Adapted from Table 1 in Seuring (2009), p. 225.

1.4. Supply Chain Strategies

There are three primary supply chain strategies on which to structure processes to build a supply chain: push, pull and push-pull strategies (Simchi-Levi, 2008, pp. 188–195; Wincel, 2004, pp. 217–225). In a push strategy, the supply chain processes are initiated based on forecasts of anticipated customer demand. In a pull strategy, the supply chain processes are initiated by a customer order being placed. Combining the two, the push-pull strategy allows forecast demand considerations to drive the supply chain processes up to a point (called the push-pull boundary). After that point, push strategy process considerations are driven by customer demand.

Although the push strategy is classic business behavior, the advent of Japanese production methods (for example, just-in-time [JIT] management, lean management) fostered a pull strategy orientation for most manufacturing firms in the 1980s (Wincel, 2004, p. 217). Not all firms can use the pull strategy. Firms that produce complex products with long lead times, or whose customers value low prices (that is, cost minimization objective for the firm), are likely to find a push strategy more workable. However, customers less interested in cost minimization and instead value firms that focus on maximizing service levels and customer responsiveness are likely to find a pull strategy more workable.

Firms today find the push-pull strategy to be highly effective if they can find the right balance in the push-pull boundary. According to Arnseth (2011b), it is possible to balance how much pushing and pulling should be undertaken to optimize this strategy. Consider the push-pull strategy along the upstream and downstream of a supply chain. Everything upstream from the manufacturing or service facility might employ a push strategy (for example, long lead times and cost minimization efforts for extra raw materials to convert them into metal sheeting), while everything downstream might employ a pull strategy based exclusively on customer demand. To avoid or minimize the potential wastefulness of the pushing upstream inputs in manufacturing distribution systems, the push-pull boundary has to be determined as early in the supply chain network as possible for customer-focused organizations. Arnseth (2011b) has suggested three ways to determine the push-pull boundary. First, coordinate the amount of pushing or pulling to the firm’s basic business model. If the firm is totally focused on customer responsiveness, the push-pull boundary will be located further upstream. Likewise, the more price sensitive customers are, the more the firm will seek greater lead times to reduce costs (that is, procurement by competitive shopping, developing less-expensive production systems), pushing the push-pull boundary downstream. Arnseth (2011b) also suggests that knowing inventory cost drivers (such as having cyclical, infrequent, or seasonal demand; low economies to scale; low purchasing power; and distance from the supplier) can all favor a push strategy. Alternatively, using a modular production process and outsourcing upsteam activities, a manufacturing organization could focus more on downstream customer demand requirements. All of these guide a demarcation of the push-pull boundary, where push strategy planning efforts end and the pull strategic planning efforts begin.

1.5. A Procedure for Supply Chain Strategy Development

There are always new supply chain executives being hired by existing firms, new firms creating supply chains, and executives launching a new strategic direction for supply chains that they manage. A strategy can be very limited to a specific domain in a supply chain (for example, acquiring new supply chain technology) or be very broad in nature impacting an entire supply chain (for example, a redesign of an entire supply chain network). Regardless of how much or how little a supply chain strategic plan might encompass, a procedure for guiding the development of a strategic plan is needed. In Figure 1.7, a proposed procedural plan leading to the development of supply chain strategies is suggested.

To begin, a supply chain executive officer or team of executives starts with broad, strategic organizational planning generalities and interprets them in terms of areas of responsibility within the supply chain management domain. To accomplish this and to aid in narrowing broad organizational objectives of the functional area, a supply chain executive could develop a vision statement to help others understand the general orientation toward a particular strategy development. A vision statement is used to define where a leader seeks to take the organization. A vision statement in supply chain management is a broad declaration defining the purpose of that functional area. It is a future-oriented statement reflecting the intentions of a supply chain executive in a role as a leader. A vision statement for a supply chain manager might be to seek an expansion in distribution management over the next couple of years to support an organizational strategic objective of market growth. The effort to generate a strategy involves translating the strategic organization goals down to the level of supply chain tactical planning. Once there, supply chain strategies to implement tactics could be developed. Figure 1.8 presents an example. To do this requires an understanding of current customer needs and the supply chain’s capabilities and limitations for meeting those needs. Despite organizational strategy desires, a supply chain may not have the ability to achieve all proposed strategic objectives of a firm. Other factors such as organizational weaknesses or potential threats might dissuade a firm from considering all objectives. Most of these are actually eliminated during the organizational strategic planning process, but others are eliminated when the realities of supply chain limitations are revealed. In this case, revisions and alignments take place to either alter planning to meet customer needs or make revisions to enhance capabilities for meeting those needs (see alignment in Figure 1.7). Once the capabilities of the supply chain are in balance with current or expected customer needs, the supply chain managers can begin implementing supply chain strategies by developing detailed tactics that move the firm toward achieving objectives by modifying the supply chain network of partners.

Figure 1.8. Example of procedure leading to the development of supply chain strategy and tactics

1.6. Starting Place for Strategy Development: Customer Value

Regardless of the outcome of any strategic planning process, the one certain and broad objective for any organization or supply chain is to seek greater value in everything. Therefore, value represents an appropriate venue for developing a supply chain strategy.

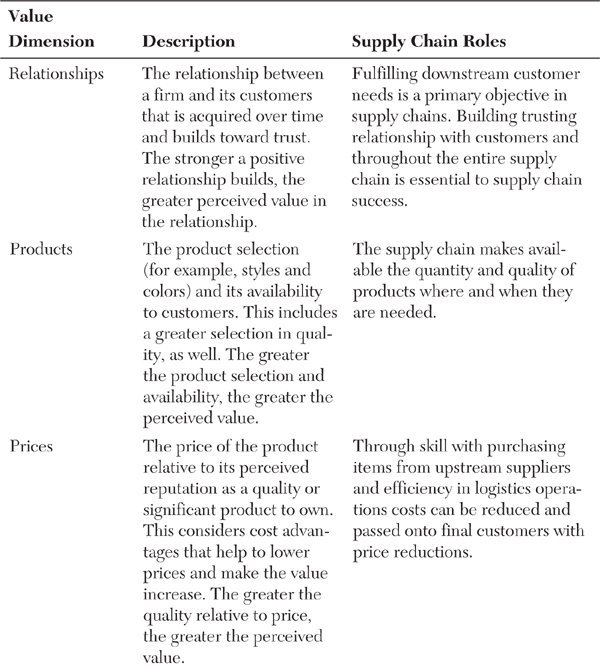

Value can be defined in terms of efficiency as the ratio of quality divided by price. Whether a supply chain partner is purchasing goods or services or selling them, the greater the ratio of quality to price, the greater is the value. Because the focus of most supply chains is to satisfy customer demand, there is a need to focus on customer value (that is, customer perception of what a firm offers in terms of products, services, and other intangibles). Based on perceptions, a customer typically employs various criteria to assess value. Primary dimensions of perceived value (see Table 1.6) can be used to develop supply chain strategies. It is not a coincidence that the dimensions of perceived customer value have some commonality to the CSFs found in the literature and based on experience. Just as it is important for a manager to build a speedy supply chain that returns profit to the organization quickly, speed is also valued by customers served by that speedy delivery system.

Table 1.6. Select Customer Value Dimensions

Source: Adapted from Fawcett et al. (2007), pp. 250–251; Simchi-Levi (2010), pp. 19–31.

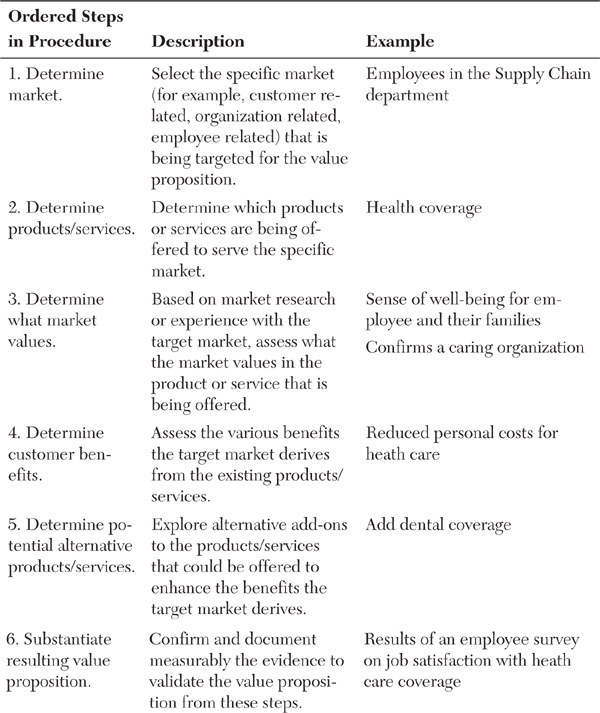

Some firms formalize customer value in a proposition. A value proposition is a statement of what the firm considers is to be value to stakeholders (that is, partners or any members within a supply chain). A value proposition can also be viewed as a promise of what stakeholders will receive in terms of a product or service. It can be applied to entire organizations, divisions, departments, customers, products, and services. A procedure for developing a value proposition is presented in Table 1.7. Value propositions can also be expressed in terms of CSFs, like those listed in Table 1.6, but usually with more specificity. For example, Wal-Mart’s “Everyday low pricing” is a customer value proposition that supports their organizational strategy of cost-efficiency. It is possible to have and utilize multiple value propositions to accommodate a wide variety of stakeholder perceptional needs.

Table 1.7. Procedure for Developing a Value Proposition

The value proposition can be used internally and externally to help direct a strategy focus regarding what the firm interprets to be of value to the customer. Internally, the analysis and results of the value proposition procedure can be used as a motivational device for employees to sell them on the concept of value and help focus efforts toward achieving product or service excellence. Externally, not everything that is collected in the value proposition procedure is shared. The resulting value proposition can be shared with external supply chain partners, customers, and suppliers. For these partners, the value proposition can used to promote areas of supply chain excellence that can be improved to reap benefits for the customer and, as an optimal outcome, build the loyalty.

1.7. What’s Next?

As you look ahead in supply chain management strategic planning, trend information based on surveys can reveal where a supply chain organization will go. Monczka and Petersen (2011) undertook a comprehensive survey of supply strategy implementation to explore future opportunities. The strategies that appear to be “what’s next” include those related to engagement of executives, vision-mission and strategic planning, commodity and supplier strategy processes, strategic cost management, procurement and supply organization structure/governance, human resource development, total cost of ownership planning, structuring and maintaining the supply base, measurement and evaluation of performance, and establishing supplier quality systems. These represent strategic areas viewed as important going forward toward 2015. Interestingly, when comparing these strategies in terms of recent implementation efforts, the gap between importance and actual implementation was significant. The results go on to suggest that Internet-based e-systems and available supply chain talent are viewed as critical enabling strategies. Growing in importance is environmental sustainability, though the survey commented that its development is not yet a major focus for many organizations. Each of these topics is discussed in the remaining chapters of this book.